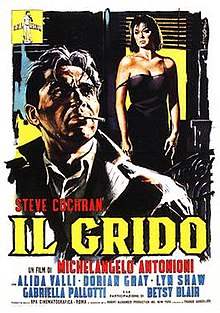

Il grido (initially titled The Cry–Il Grido in the UK and The Outcry in the US)[2] is a 1957 Italian drama film directed by Michelangelo Antonioni and starring Steve Cochran, Alida Valli, and Betsy Blair.[3][4] It received the Golden Leopard at the 1957 Locarno Film Festival.[5] In 2008, the film was included on the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage’s 100 Italian films to be saved, a list of 100 films that "have changed the collective memory of the country between 1942 and 1978."[6]

| Il grido | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michelangelo Antonioni |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Michelangelo Antonioni |

| Produced by | Franco Cancellieri |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gianni di Venanzo |

| Edited by | Eraldo Da Roma |

| Music by | Giovanni Fusco |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | CEIAD |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Box office | $11,947[1] |

Plot

editThe story centers on Aldo, a mechanic working in a sugar refinery in the Po Valley town of Goriano, Northern Italy. He has been in a seven-year relationship with Irma, with whom he shares a daughter, Rosina. When Irma learns that her estranged husband, who left for Australia years earlier, has died, Aldo sees an opportunity to marry her and legitimize their daughter. However, Irma confesses that she has fallen in love with another man. Devastated, Aldo attempts to win her back, but after a public altercation where he slaps her, Irma ends the relationship definitively.

In response to his heartbreak, Aldo leaves Goriano with Rosina, embarking on a journey through the Po Valley. Their first stop is at the home of Elvia, Aldo's former girlfriend, who works as a seamstress. Aldo tries to rekindle their past relationship, but his lingering sorrow over Irma hinders any genuine connection. Irma visits Elvia to deliver Aldo's belongings and informs her of their separation. Elvia confronts Aldo about returning only after his breakup and encourages him to move on. Realizing he cannot stay, Aldo departs with Rosina the next morning.

As they continue traveling, Aldo struggles to find steady work that accommodates Rosina's schooling. Their relationship becomes strained, culminating in an incident where Aldo slaps Rosina after she nearly gets hit by a car. They hitch a ride atop a petrol truck but are forced to disembark before a police checkpoint. Seeking shelter, they arrive at a filling station run by Virginia, a young widow living with her elderly father. She offers them a place to stay and gives Aldo a job. Over time, Aldo and Virginia become romantically involved.

Rosina spends her days with Virginia's father, who is bitter about selling his farmland and exhibits erratic behavior. Frustrated, Virginia decides to place him in a retirement home. Tensions escalate when Rosina witnesses Aldo and Virginia's intimacy, prompting Virginia to suggest that they can no longer care for the child. Aldo reluctantly sends Rosina back to Irma, chasing after the departing bus to declare his love for his daughter.

After parting ways with Virginia, Aldo finds employment with a dredge crew and contemplates moving to Venezuela, even beginning to learn Spanish. However, he soon loses interest. He befriends Andreina, a local prostitute, helping her secure medical attention. Mistakenly believing the police are after him, Aldo flees, leaving his coat behind. Andreina locates him, and they share stories of their troubled pasts. Heavy rains and scarce resources strain their situation, leading Andreina to seek food by offering herself to a restaurant owner. A confrontation ensues, and an exasperated Aldo abandons her.

Returning to Goriano, Aldo encounters Virginia at the filling station. She returns his belongings and mentions a misplaced postcard from Irma, inciting Aldo's frustration. In Goriano, he discovers the town in turmoil over the construction of an airfield that threatens to displace residents. Observing from a distance, Aldo sees Rosina entering Irma's home and notices Irma caring for a new child. Irma spots him and follows as he makes his way to the deserted sugar refinery where he once worked.

Aldo climbs the refinery tower, appearing disoriented and weary. From below, Irma calls out to him. He turns to see her but then falls to his death. Irma rushes to his side, grieving over his lifeless body as townspeople pass by en route to a protest rally.

Cast

edit- Steve Cochran as Aldo

- Alida Valli as Irma

- Betsy Blair as Elvia

- Gabriella Pallotta as Edera, Elvia's sister

- Dorian Gray as Virginia (dubbed by Monica Vitti)[7]

- Lyn Shaw as Andreina

- Mirna Girardi as Rosina

- Pina Boldrini as Lina, Irma's sister

- Guerrino Campanilli as Virginia's father

- Pietro Corvelatti as Fisherman

- Lilia Landi as Woman

- Gaetano Matteucci as Edera's fiancé

- Elli Parvo as Donna Matilda

Production and release

editAntonioni had written the script for Il grido in the late 1940s while working on another production in the Po area.[3] The film was realised as an Italian–American co-production and shot in Winter 1956/1957 on location in the lower Po Valley, including Occhiobello, Pontelogoscuro, Ferrara, Stienta and Ca'Venier.[3] Antonioni later spoke of problems he had with some of his foreign actors: with Betsy Blair, because she wanted the meaning behind her complete dialogue explained in detail, and with Steve Cochran for regularly refusing to follow the director's instructions.[8]

Il grido premiered at the Locarno Film Festival on 14 July 1957[3] and in Rome on 29 November 1957.[4] Of the films Antonioni had made up to this point, Il grido proved to be the least successful at the box office, earning a mere 25 million lire during its initial release.[9]

In English speaking countries, the film saw a delayed release, in late 1961 in the UK and in October 1962 in the US.[2] In the US, it was also shown in a dubbed and shortened version, released by Astor Pictures.[2]

Reception

editWhile Antonioni's previous film Le Amiche had been artistically acknowledged by Italian critics, the reactions towards Il grido were, depending on the source, unanimously negative[3] or sympathetic only in a handful of cases,[10] calling its director "cold" and "inhuman".[7] (Contrary to this, Seymour Chatman in Michaelangelo Antonioni: The Investigation cites Il grido as his "first genuine critical success".)[11] In a later interview, Antonioni explained that he had been in a state of depression at the time, and that the film reflected this in a more pessimistic, desperate tone.[7] As a result of the film's disappointing domestic reception, Antonioni was forced to cancel planned film projects and turn to theatre work, before returning to the cinema with his 1960 L'Avventura.[3]

On the occasion of the film's 1962 New York release (where it was screened in Italian with English subtitles), The New York Times critic A. H. Weiler saw an "interesting, sometimes arresting slice of life at the lower depths", but the outlook of its director as "dismal and depressed".[12] F. Maurice Speed, writing for the British Film Review, was more enthusiastic, calling it "brilliant" and "sad, fascinating and finely directed".[2]

Themes

editIn retrospect, critics such as Leslie Camhi (The Village Voice), Philip French (The Guardian)[13] and Keith Phipps (The A.V. Club) saw Il grido as a transitional work between Antonioni's neorealist roots and his later films.[14][15] In her 1984 analysis of Italian cinema, Mira Liehm writes that while Il grido contains neo-realist elements, "particularly the interdependence between the landscapes and the characters and the emphasis on objects", protagonist Aldo "foreshadows Sandro in L'avventura and Giovanni in La notte in his refusal to acknowledge the fading of love".[16]

Reviewers disagree about whether Aldo's death at the end is intentional or not. While French critic Gérard Gozlan (Positif) saw it as a suicide,[17] Seymour Chatman argues that Aldo is overcome with vertigo as he stands atop the tower, causing him to fall to his death. Chatman found support in the original screenplay, which mentions that Aldo attempts to resist a sudden onset of vertigo as he looks down on the ground.[4] Peter Brunette regards the ending as being ambiguous: Aldo's death can be viewed either as caused by a fall or a deliberate jump.[9]

Liehm, Brunette and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith also point out that as an exception in Antonioni's films, the protagonist of Il grido is a member of the working class instead of the bourgeoisie,[16][9][10] an observation confirmed by the director in an interview in which he stated that only Il grido and his early documentary short Gente del Po (1947) were about working class concerns.[7]

Awards

edit- 1957 Locarno International Film Festival: Golden Leopard for Michelangelo Antonioni

- 1958 Nastro d'Argento for Best Cinematography (Gianni di Venanzo)

In popular culture

editIn Alfred Andersch's 1960 novel Die Rote (The Redhead), protagonist Fabio reflects on Antonioni's film.[3]

References

edit- ^ "II Grido". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Pitts, Michael R. (2019). Astor Pictures: A Filmography and History of the Reissue King, 1933-1965. McFarland. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9781476676494.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jansen, Peter W.; Schütte, Wolfram, eds. (1984). Michaelangelo Antonioni. Munich and Vienna: Carl Hanser Verlag.

- ^ a b c Chatman, Seymour (1985). Antonioni, or, The Surface of the World. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05341-0.

- ^ "Winners of the Golden Leopard". Locarno. Archived from the original on 2009-07-19. Retrieved 2012-08-12.

- ^ "Ecco i cento film italiani da salvare Corriere della Sera". www.corriere.it. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- ^ a b c d Cardullo, Bert, ed. (2008). Michelangelo Antonioni: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. p. XXV. ISBN 9781934110669.

- ^ "Michelangelo Antonioni on Il grido". Il grido (DVD release booklet). Eureka Entertainment. 2009.

- ^ a b c Brunette, Peter (1998). The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-521-38992-1.

- ^ a b Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey (2019). L'avventura. Bloomsbury. p. 19. ISBN 9780851705347.

- ^ Chatman, Seymour (2004). Michaelangelo Antonioni: The Investigation. Taschen. p. 45. ISBN 9783822830895.

- ^ Weiler, A.H. (23 October 1962). "Antonioni's 'Il grido' Arrives: '57 Film a Forerunner of 'L' Avventura'". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ French, Philip (31 May 2009). "Philip French's classic DVD: Il grido". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ Camhi, Leslie (30 July 2002). "Distribute the Wealth". The Village Voice. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ Phipps, Keith (March 29, 2002). "Il grido". A.V. Club. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ a b Liehm, Mira (1984). Passion and Defiance: Italian Film from 1942 to the Present. University of California Press. pp. 156–59. ISBN 9780520057449.

- ^ Gozlan, Gérard (July–August 1960). "Le Cri ou la faillite de nos sentiments". Positif. No. 35.

Bibliography

edit- Arrowsmith, William (1995). Ted Perry (ed.). Antonioni: The Poet of Images. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509270-7.

- Brunette, Peter (1998). The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38992-1.

External links

edit- Il Grido at IMDb

- Il Grido at AllMovie

- Il grido at Rotten Tomatoes

- Brown, James (May 2003). "Il grido: Modernising the Po". Senses of Cinema.

- Schwartz, Dennis (2004). "Il grido". Dennis Schwartz Movie Reviews. Retrieved 31 January 2023.