This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) |

West Frisian, or simply Frisian (West Frisian: Frysk [frisk] or Westerlauwersk Frysk; Dutch: Fries [fris], also Westerlauwers Fries), is a West Germanic language spoken mostly in the province of Friesland (Fryslân) in the north of the Netherlands, mostly by those of Frisian ancestry. It is the most widely spoken of the Frisian languages.

| West Frisian | |

|---|---|

| Frisian | |

| Frysk Westerlauwersk Frysk | |

| Pronunciation | [frisk], [ˈʋɛstr̩ˌlɔu.əs(k) ˈfrisk] |

| Native to | Netherlands |

| Region | Friesland |

| Ethnicity | West Frisians |

Native speakers | 470,000 (2001 census)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Netherlands |

| Regulated by | Fryske Akademy |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | fy |

| ISO 639-2 | fry |

| ISO 639-3 | fry |

| Glottolog | west2354 |

| ELP | West Frisian |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACA-b |

Present-day distribution West Frisian languages, in the Netherlands | |

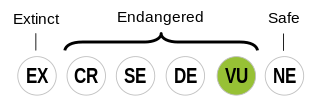

Frisian is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

In the study of the evolution of English, West Frisian is notable as being the most closely related foreign tongue to the various dialects of Old English spoken across the Heptarchy, these being part of the Anglo-Frisian branch of the West Germanic family.

Name

editThe name "West Frisian" is only used outside the Netherlands, to distinguish this language from the closely related Frisian languages of East Frisian, including Saterland Frisian, and North Frisian spoken in Germany. Within the Netherlands, however, "West Frisian" refers to the West Frisian dialect of the Dutch language while the West Frisian language is almost always just called "Frisian" (in Dutch: Fries for the Frisian language and Westfries for the Dutch dialect). The unambiguous name used for the West Frisian language by linguists in the Netherlands is Westerlauwers Fries [ˈʋɛstərˌlʌu.ərs ˈfris] (West Lauwers Frisian), the Lauwers being a border river that separates the Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen.

History

editOld Frisian

editIn the early Middle Ages the Frisian lands stretched from the area around Bruges, in what is now Belgium, to the river Weser, in northern Germany. At that time, the Frisian language was spoken along the entire southern North Sea coast. Today this region is sometimes referred to as "Greater Frisia" or Frisia Magna, and many of the areas within it still treasure their Frisian heritage, even though in most places the Frisian language has been lost.

Old Frisian bore a striking similarity to Old English. This similarity was reinforced in the late Middle Ages by the Ingvaeonic sound shift, which affected Frisian and English, but the other West Germanic varieties hardly at all. Both English and Frisian are marked by the suppression of the Germanic nasal in a word like us (ús), soft (sêft) or goose (goes): see Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law. Also, when followed by some vowels, the Germanic k developed into a ch sound. For example, the West Frisian for cheese and church is tsiis and tsjerke, whereas in Dutch they are kaas and kerk. Modern English and Frisian on the other hand have become very divergent, largely due to wholesale Old Norse and Anglo-Norman imports into English and similarly heavy Dutch and Low German influences on Frisian.

One major difference between Old Frisian and modern Frisian is that in the Old Frisian period (c. 1150 – c. 1550) grammatical cases still occurred. Some of the texts that are preserved from this period are from the 12th or 13th, but most are from the 14th and 15th centuries. Generally, these texts are restricted to legal documents. Although the earliest definite written examples of Frisian are from approximately the 9th century, there are a few runic inscriptions from the region which are probably older and possibly in the Frisian language. These runic writings, however, usually do not amount to more than single- or few-word inscriptions, and cannot be said to constitute literature as such. The Middle Frisian language period (c. 1550 – c. 1820) is rooted in geopolitics and the consequent fairly abrupt halt in the use of Frisian as a written language.

Middle Frisian and New Frisian

editUntil the 16th century, West Frisian was widely spoken and written, but from 1500 onwards it became an almost exclusively oral language, mainly used in rural areas. This was in part due to the occupation of its stronghold, the Dutch province of Friesland (Fryslân), in 1498, by Albert III, Duke of Saxony, who replaced West Frisian as the language of government with Dutch.

This practice was continued under the Habsburg rulers of the Netherlands (Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and his son Philip II, King of Spain). When the Netherlands became independent in 1585, West Frisian did not regain its former status, because Holland rose as the dominant part of the Netherlands and its language, Dutch, as the dominant language in judicial, administrative and religious affairs.

In this period the Frisian poet Gysbert Japiks (1603–1666), a schoolteacher and cantor from the city of Bolsward (Boalsert), who largely fathered modern West Frisian literature and orthography, was an exception to the rule.

His example was not followed until the 19th century, when entire generations of Frisian authors and poets appeared. This coincided with the introduction of the so-called newer breaking system, a prominent grammatical feature in almost all West Frisian dialects, with the notable exception of Súdwesthoeksk. Therefore, the New Frisian period is considered to have begun at this time, around 1820.

Speakers

editMost speakers of West Frisian live in the province of Friesland in the north of the Netherlands. Friesland has 643,000 inhabitants (2005), of whom 94% can understand spoken West Frisian, 74% can speak West Frisian, 75% can read West Frisian, and 27% can write it.[2]

For over half of the inhabitants of the province of Friesland, 55% (c. 354,000 people), West Frisian is the native language. In the central east, West Frisian speakers spill over the province border, with some 4,000–6,000 of them actually living in the province of Groningen, in the triangular area of the villages Marum (West Frisian: Mearum), De Wilp (De Wylp), and Opende (De Grinzer Pein).[3]

Also, many West Frisians have left their province in the last 60 years for more prosperous parts of the Netherlands. Therefore, possibly as many as 150,000 West Frisian speakers live in other Dutch provinces, particularly in the urban agglomeration in the West, and in neighbouring Groningen and newly reclaimed Flevoland.[citation needed]

A Frisian diaspora exists abroad; Friesland sent more emigrants than any other Dutch province between the Second World War and the 1970s. Frisian is still spoken by some Dutch Canadians, Dutch Americans, Dutch Australians and Dutch New Zealanders.

Apart from the use of West Frisian as a first language, it is also spoken as a second language by about 120,000 people in the province of Friesland.[4]

West Frisian is considered by UNESCO to be a language in danger of becoming extinct, officially listed as "vulnerable".[5]

Status

editIn 1951, Frisian language activists, protesting at the exclusive use of Dutch in the courts, caused a riot in Leeuwarden.[6] The resulting inquiry led to the establishment of a committee of inquiry. This committee recommended that the Frisian language should receive legal status as a minority language.[7] Subsequently, the Use of Frisian in Legal Transactions Act of 11 May 1956 was passed, which provided for the use of Frisian in transactions with the courts.[8]

Since 1956, West Frisian has an official status along with and equal to Dutch in the province of Friesland. It is used in many domains of Frisian society, among which are education, legislation, and administration. In 2010, some sixty public transportation ticket machines in Friesland and Groningen added a West Frisian-language option.[9]

Although in the courts of law the Dutch language is still mainly used, in the province of Friesland, Frisians have the right to give evidence in their own language. Also, they can take the oath in Frisian in courts anywhere in the Netherlands.

Primary education in Friesland was made bilingual in 1956, which means West Frisian can be used as a teaching medium. In the same year, West Frisian became an official school subject, having been introduced to primary education as an optional extra in 1937. It was not until 1980, however, that West Frisian had the status of a required subject in primary schools, and not until 1993 that it was given the same position in secondary education.

In 1997, the province of Friesland officially changed its name from the Dutch form Friesland to the West Frisian Fryslân. So far 4 out of 18 municipalities (Dantumadiel, De Fryske Marren, Noardeast-Fryslân, Súdwest-Fryslân) have changed their official geographical names from Dutch to West Frisian. Some other municipalities, like Heerenveen and the 11 towns, use two names (both Dutch and West Frisian) or only a West Frisian name.

Within ISO 639 West Frisian falls under the codes fy and fry, which were assigned to the collective Frisian languages.

Relations with Dutch and English

editWith Dutch

editThe mutual intelligibility in reading between Dutch and Frisian is poor. A cloze test in 2005 revealed native Dutch speakers understood 31.9% of a West Frisian newspaper, 66.4% of an Afrikaans newspaper and 97.1% of a Dutch newspaper. However, the same test also revealed that native Dutch speakers understood 63.9% of a spoken Frisian text, 59.4% of a spoken Afrikaans text and 89.4% of a spoken Dutch text, read aloud by native speakers of the respective languages.[10]

Folklore about relation to English

editThe saying "As milk is to cheese, are English and Fries" describes the observed similarity between Frisian and English. One rhyme that is sometimes used to demonstrate the palpable similarity between Frisian and English is "Bread, butter and green cheese is good English and good Fries", which does not sound very different from "Brea, bûter en griene tsiis is goed Ingelsk en goed Frysk".[11]

Another rhyme on this theme, "Bûter, brea en griene tsiis; wa't dat net sizze kin is gjin oprjochte Fries" (ⓘ; in English, "Butter, bread and green cheese, whoever can't say that is not a proper Frisian") was used, according to legend, by the 16th century Frisian rebel and pirate Pier Gerlofs Donia as a shibboleth that he forced his captives to repeat to distinguish Frisians from Dutch and Low Germans.

Language examples

editHere is a short example of the West Frisian language in comparison with English, Old English, and Dutch.

| Language | Text |

|---|---|

| English[12] | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

| Old English[13] | Ealle menn sindon frēo and ġelīċe on āre and ġerihtum ġeboren. Hīe sindon witt and inġehygde ġetīðod, and hīe sċulon mid brōþorlīċum ferhþe tō heora selfes dōn. |

| West Frisian[14] | Alle minsken wurde frij en gelyk yn weardigens en rjochten berne. Hja hawwe ferstân en gewisse meikrigen en hearre har foar inoar oer yn in geast fan bruorskip te hâlden en te dragen. |

| Dutch[15] | Alle mensen worden vrij en gelijk in waardigheid en rechten geboren. Zij zijn begiftigd met verstand en geweten, en behoren zich jegens elkander in een geest van broederschap te gedragen. |

Internal classification

editNot all Frisian varieties spoken in Dutch Friesland are mutually intelligible. The varieties on the islands are rather divergent, and Glottolog distinguishes four languages:[16]

- Hindeloopen-Molkwerum Frisian

- Schiermonnikoog Frisian

- Westlauwers–Terschellings

- Terschelling Frisian

- Western Frisian (mainstream Mainland West Frisian)

The dialects within mainstream mainland West Frisian are all readily intelligible. Three are usually distinguished:

- Clay Frisian (Klaaifrysk dialect)

- Wood Frisian (Wâldfrysk dialect, incl. Westereendersk)

- South or Southwest Frisian (Súdhoeksk dialect)

The Súdwesthoeksk ("South Western") dialect, which is spoken in an area called de Súdwesthoeke ("the Southwest Corner"), deviates from mainstream West Frisian in that it does not adhere to the so-called newer breaking system, a prominent grammatical feature in the three other main dialects.

The Noardhoeksk ("Northern") dialect, spoken in the north eastern corner of the province, does not differ much from Wood Frisian.

By far the two most-widely spoken West Frisian dialects are Clay Frisian (Klaaifrysk) and Wood Frisian (Wâldfrysk). Both these names are derived from the Frisian landscape. In the western and north-western parts of the province, the region where Clay Frisian is spoken, the soil is made up of thick marine clay, hence the name. While in the Clay Frisian-speaking area ditches are used to separate the pastures, in the eastern part of the province, where the soil is sandy, and water sinks away much faster, rows of trees are used to that purpose. The natural landscape in which Wâldfrysk exists mirrors The Weald and North Weald areas of south-eastern England – the Germanic words wald and weald are cognate.

Although Klaaifrysk and Wâldfrysk are mutually very easily intelligible, there are, at least to native West Frisian speakers, a few very conspicuous differences. These include the pronunciation of the words my ("me"), dy ("thee"), hy ("he"), sy ("she" or "they"), wy ("we") and by ("by"), and the diphthongs ei and aai.[17]

Of the two, Wâldfrysk probably has more speakers, but because the western clay area was originally the more prosperous part of the mostly agricultural province, Klaaifrysk has had the larger influence on the West Frisian standardised language.

Dialectal comparison

editThere are few if any differences in morphology or syntax among the West Frisian dialects, all of which are easily mutually intelligible, but there are slight variances in lexicon.[18]

Phonological differences

editThe largest difference between the Clay Frisian and Wood Frisian dialects are the words my ("me"), dy ("you"), hy ("he"), sy ("she" or "they"), wy ("we"), and by ("by"), which are pronounced in the Wood Frisian as mi, di, hi, si, wi, and bi and in Clay Frisian as mij, dij, hij, sij, wij, and bij. Other differences are in the pronunciation of the diphthongs ei, ai, and aai which are pronounced ij, ai, and aai in Wood Frisian, but ôi, òi, and ôi in Clay Frisian. Thus, in Wood Frisian, there is no difference between ei and ij, whereas in Clay Frisian, there is no difference between ei and aai.

Other phonological differences include:

| English | Dutch | Wood Frisian | Clay Frisian |

|---|---|---|---|

| you (singular) | jij | dû | do |

| plum | pruim | prûm | prom |

| thumb | duim | tûme | tomme |

| naked | naakt | nêken | neaken |

| crack | kraken | krêkje | kreakje |

| weak (soft) | week | wêk | weak |

| grass | gras | gjers | gers |

| cherry | kers | kjers | kers |

| calf | kalf | kjel | kel |

Lexical differences

editSome lexical differences between Clay Frisian and Wood Frisian include:

| English | Wood Frisian | Clay Frisian |

|---|---|---|

| Saturday | saterdei | sneon |

| ant | mychammel mychhimmel |

eamel eamelder |

| fleece | flij | flues |

| sow (pig) | mot | sûch |

Orthography

editWest Frisian uses the Latin alphabet. A, E, O and U may be accompanied by circumflex or acute accents.

In alphabetical listings both I and Y are usually found between H and J. When two words differ only because one has I and the other one has Y (such as stikje and stykje), the word with I precedes the one with Y.

In handwriting, IJ (used for Dutch loanwords and personal names) is written as a single letter (see IJ (digraph)), whereas in print the string IJ is used. In alphabetical listings IJ is most commonly considered to consist of the two letters I and J, although in dictionaries there is an entry IJ between X and Z telling the user to browse back to I.

Phonology

editThis article should include a summary of West Frisian phonology. (March 2015) |

Grammar

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ West Frisian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Provinsje Fryslân (2007), Fluchhifking Fryske Taal.

- ^ Gorter, D. L.G. Jansma en G.H. Jelsma (1990), Taal yn it Grinsgebiet. Undersyk nei de taalferhâldings en de taalgrins yn it Westerkertier yn Grinslân. Sosjaal-wittenskiplike rige nummer 10. Akademy-nummer 715. Ljouwert: Fryske Akademy.

- ^ Gorter, D. & R.J. Jonkman (1994), Taal yn Fryslân op 'e nij besjoen. Ljouwert: Fryske Akademy.

- ^ Moseley, Christopher, ed. (2010). Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. Memory of Peoples (3rd ed.). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-104096-2.

- ^ Geschiedenis van Friesland, 1750–1995, Johan Frieswijk, p. 327.

- ^ Buruma, Ian (31 May 2001). "The Road to Babel". The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504.

- ^ see Wet gebruik Friese taal in het rechtsverkeer [Use of Frisian in Legal Transactions Act] (in Dutch) via overheid.nl

- ^ "Ov-chipkaartautomaten ook in het Fries" [OV chip card machines also in Frisian]. de Volkskrant. 13 September 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Bezooijen, Renée van; Gooskens, Charlotte (2005). "How easy is it for speakers of Dutch to understand Frisian and Afrikaans, and why?" (PDF). Linguistics in the Netherlands. 22: 18, 21, 22.

- ^ The History of English: A Linguistic Introduction, Scott Shay. Wardja Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-615-16817-3

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights - English". OHCHR. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ "UDHR in Germanic languages". Omniglot. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights - Frisian". OHCHR. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights - Dutch (Nederlands)". OHCHR. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2020). "Western Frisian". Glottolog 4.3.

- ^ Popkema, J. (2006), Grammatica Fries. De regels van het Fries. Utrecht: Het Spectrum.

- ^ Ana Deumert, Wim Vandenbussche (2003). Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 90-272-1856-0.

Further reading

edit- Erkelens, Helma (2004), Taal fen it hert. Language of the Heart. About Frisian Language and Culture (PDF), Leeuwarden: Province of Fryslân

- de Haan, Germen J. (2010), Hoekstra, Jarich; Visser, Willem; Jensma, Goffe (eds.), Studies in West Frisian Grammar: Selected Papers by Germen J. de Haan, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, ISBN 978-90-272-5544-0

- Hoekstra, Jarich; Tiersma, Peter Meijes (2013) [First published 1994], "16 Frisian", in van der Auwera, Johan; König, Ekkehard (eds.), The Germanic Languages, Routledge, pp. 505–531, ISBN 978-0-415-05768-4

- Jong, Gerbrich de; Hoekstra, Eric (2018), "A General Introduction to Frisian", Taalportaal

- Jonkman, Reitze J. (1999), "Leeuwarden" (PDF), in Kruijsen, Joep; van der Sijs, Nicoline (eds.), Honderd Jaar Stadstaal, Uitgeverij Contact, pp. 37–48

- Sipma, Pieter (1913), Phonology & grammar of modern West Frisian, London: Oxford University Press

External links

edit- ISO 639 code set entry for "fry" and for "fri" (active and retired language codes, respectively)

- Wet gebruik Friese taal (2013). overheid.nl. - 2013 legislation concerning the Frisian language