Atransferrinemia is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder in which there is an absence of transferrin, a plasma protein that transports iron through the blood.[2][4] Atransferrinemia is characterized by anemia and hemosiderosis in the heart and liver. The iron damage to the heart can lead to heart failure. The anemia is typically microcytic and hypochromic (the red blood cells are abnormally small and pale). Atransferrinemia was first described in 1961 and is extremely rare, with only ten documented cases worldwide.[5]

| Atransferrinemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | familial atransferrinemia |

| |

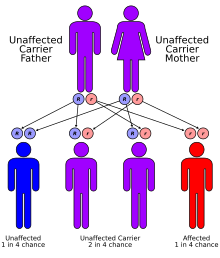

| Atransferrinemia has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, meaning both copies of the gene in each cell are defective. | |

| Symptoms | Anemia[1] |

| Causes | Mutations in the TF gene[2] |

| Diagnostic method | TF level, Physical exam[2] |

| Treatment | Oral iron therapy[3] |

Symptoms and signs

editThe presentation of this disorder entails anemia, arthritis, hepatic anomalies, and recurrent infections are clinical signs of the disease.[1] Iron overload occurs mainly in the liver, heart, pancreas, thyroid, and kidney.[6]

Genetics

editIn terms of genetics of atransferrinemia researchers have identified mutations in the TF gene as a probable cause of this genetic disorder in affected people.[2]

Transferrin is a serum transport protein that transports iron to the reticuloendothelial system for utilization and erythropoiesis, since there is no transferrin in atransferrinemia, serum free iron cannot reach reticuloendothelial cells and there is microcytic anemia.[7][8][9]

Diagnosis

editThe diagnosis of atransferrinemia is done via the following means to ascertain if an individual has the condition:[2]

- Blood test(for anemia)

- TF level

- Physical exam

- Genetic test

Types

editThere are two forms of this condition that causes an absence of transferrin in the affected individual:[10]

- Acquired atransferrinemia

- Congenital atransferrinemia

Treatment

editThe treatment of atransferrinemia is apotransferrin. The missing protein without iron. Iron treatment is detrimental as it does not correct the anemia and is a cause of secondary hemochromatosis.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Atransferrinemia | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- ^ a b c d e RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Congenital atransferrinemia". www.orpha.net. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hoffman, Ronald; Benz, Edward J. Jr.; Silberstein, Leslie E.; Heslop, Helen; Weitz, Jeffrey; Anastasi, John (2012). Hematology: Diagnosis and Treatment. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 443. ISBN 978-1455740413.

- ^ "OMIM Entry - # 209300 - ATRANSFERRINEMIA". omim.org. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "Atransferrinemia". National Organization for Rare Disorders. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ Barton, James C.; Edwards, Corwin Q. (2001). Hemochromatosis: Genetics, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Cambridge University Press. p. 212. ISBN 9780521593809.

- ^ Bartnikas, Thomas Benedict (1 August 2012). "Known and potential roles of transferrin in iron biology". BioMetals. 25 (4): 677–686. doi:10.1007/s10534-012-9520-3. PMC 3595092. PMID 22294463.

- ^ Reference, Genetics Home. "TF gene". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- ^ "OMIM Entry - * 190000 - TRANSFERRIN; TF". omim.org. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ Marks, Vincent; Mesko, Dusan (2002). Differential Diagnosis by Laboratory Medicine: A Quick Reference for Physicians. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 633. ISBN 9783540430575. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

Further reading

edit- Handin, Robert I.; Lux, Samuel E.; Stossel, Thomas P. (2003-01-01). Blood: Principles and Practice of Hematology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781719933.

- Mazza, Joseph (2002-01-01). Manual of Clinical Hematology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781729802.