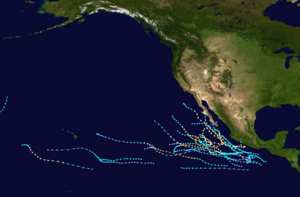

The 1984 Pacific hurricane season featured numerous tropical cyclones, several of which were impactful to land. It was a busy hurricane season with 21 named storms, 13 hurricanes, and 7 major hurricanes, the latter of which are Category 3 or stronger cyclones on the Saffir–Simpson scale. This activity was unusual given the presence of a La Niña, which typically suppresses Central and East Pacific tropical cyclone activity, and only average sea surface temperatures.[1] Seasonal activity began on May 17 and ended on November 8. This lies within the confines of a traditional hurricane season which begins on May 15 in the East Pacific and June 1 in the Central Pacific, and ends on November 30 in both basins. These dates conventionally delimit the period during each year when most tropical cyclones form.[2]

| 1984 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 17, 1984 |

| Last system dissipated | November 8, 1984 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Douglas |

| • Maximum winds | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 939 mbar (hPa; 27.73 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 21 |

| Hurricanes | 13 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 7 |

| Total fatalities | ≥24 |

| Total damage | $140 million (1984 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The drought-stricken Hawaiian Islands received beneficial rainfall from Hurricane Douglas in July and Tropical Storm Kenna in August. The remnants of hurricanes Iselle, Marie, Norbert, and Odile all contributed to enhanced precipitation across the Southwestern United States during the season, including snowfall in higher elevations; flash flooding killed one person in Texas. Hurricane Lowell attracted widespread coverage for damaging the Blue Falcon and forcing the rescue of its 23 crewmembers. In September, torrential rains from Hurricane Odile in Southern Mexico severely damaged crops, inflicted water damage to about 900 homes, and left thousands of residents displaced or without normal services. The storm killed at least 21 people. Multiple hurricanes contributed to rough surf along the California coastline, resulting in one death and hundreds of water rescues.

Systems

edit

Tropical Storm Alma

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 17 – May 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

On May 13, an area of disturbed weather within the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) crossed Panama and Colombia into the East Pacific. Strong westerly wind shear inhibited this disturbance initially, but atmospheric conditions improved over subsequent days,[3] allowing it to become the season's first tropical depression around 18:00 UTC on May 17.[4] The system increased rapidly in size as developing high pressure to its north brought it over very warm ocean waters.[3] The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Alma by 18:00 UTC on May 18, attaining peak winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) the next day. After fluctuating in intensity for a few days, Alma weakened to a tropical depression and dissipated after 18:00 UTC on May 21.[4]

Hurricane Boris

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 28 – June 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical depression developed south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec around 18:00 UTC on May 28. It intensified into Tropical Storm Boris over the next six hours, and further development allowed it to become the season's first hurricane by 12:00 UTC on May 30. After reaching peak winds of 75 mph (121 km/h), Boris weakened and began to move erratically as upper-level troughing progressed over western Mexico. The storm conducted a counter-clockwise loop over numerous days, finally tracking west again as ridging redeveloped to its north.[3] The system, which had persisted as a tropical depression during that time, regained tropical storm intensity on June 13 before crossing into cooler waters.[3] Boris dissipated after 00:00 UTC on June 18 to the southwest of the Baja California Peninsula.[4]

Hurricane Cristina

edit| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 17 – June 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); |

A weak cold-core low drifted westward across the southern Gulf of Mexico,[3] acting as the impetus for a tropical depression that formed south of Mexico around 06:00 UTC on June 17. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Cristina within six hours and further organized into a hurricane around 18:00 UTC on June 19. The next day, it attained Category 2 strength with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h).[4] High pressure over Oklahoma, and upper-level troughing over southern California, both retrograded west as Cristina developed. This caused the storm to track in stair-step fashion throughout its duration. The cyclone weakened to a tropical storm on August 21, but it regained hurricane strength two days later before feeling the effects of an upper-level trough off Baja California.[3] Cristina weakened rapidly, dissipating after 00:00 UTC on June 26.[4]

Hurricane Douglas

edit| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 25 – July 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min); 939 mbar (hPa) |

An area of disturbed weather formed east of Clipperton Island on June 23, organizing into a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on June 25. The newly developed system moved west-northwest and intensified over warm waters,[3] becoming Tropical Storm Douglas by 18:00 UTC on June 25 and strengthening into a hurricane about 48 hours later. In a 24-hour period ending at 00:00 UTC on June 29, the cyclone's winds increased from 85 to 145 mph (137 to 233 km/h), equivalent to Category 4 intensity.[4] At its peak, Douglas displayed a well-defined eye on satellite imagery. After persisting as an intense hurricane for several days, it encountered waters cooler than 77 °F (25 °C) on July 2 and began to weaken.[3] Douglas crossed into the Central Pacific as a tropical depression the following day, where it ultimately dissipated after 18:00 UTC on July 6.[4] The remnants of the cyclone crossed Maui and the Big Island on July 8–9, where it produced rainfall accumulations up to 2 in (51 mm) over the parched slopes of those islands.[5]

Hurricane Elida

edit| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 28 – July 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical disturbance formed south of Salina Cruz, Oaxaca, on June 26 and was upgraded to a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on June 28.[3] By 12:00 UTC the next day, the system intensified into Tropical Storm Elida. Like Douglas before it, Elida entered a period of rapid intensification and became a Category 4 hurricane, peaking with winds of 130 mph (210 km/h). The cyclone fluctuated in intensity before starting a more definitive weakening trend after July 3.[4] Around this time, the steering regime around Elida collapsed, causing the system to backtrack toward the east within low-level flow imparted by Tropical Storm Fausto to the north and Hurricane Genevieve to the east. Tracking over cold waters,[3] the system dissipated after 18:00 UTC on July 8.[4]

Hurricane Fausto

edit| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 3 – July 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); |

An area of disturbed weather crossed Guatemala into the East Pacific on July 1. It passed over extremely warm waters and rapidly organized accordingly,[3] becoming a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC on July 3 and a tropical storm, Fausto, six hours later.[4] The newly formed cyclone moved northwest, guided by two potent upper-level troughs to its north.[3] Fausto became a hurricane around 18:00 UTC on July 4 and further developed into a Category 2 storm with winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) at 00:00 UTC on July 6. After maintaining hurricane strength until July 8,[4] Fausto entered progressively cooler waters and began to weaken. Ridging became established north of the storm,[3] which curved west and dissipated after 00:00 UTC on July 10.[4]

Hurricane Genevieve

edit| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 7 – July 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); |

To the southeast of Hurricane Fausto, a new area of disturbed weather formed south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec on July 6.[3] The system coalesced into a tropical depression by 06:00 UTC on July 7; within twelve hours, it became Tropical Storm Genevieve.[4] The system moved northwest parallel to the Mexico coastline, and warm waters facilitated its continued development.[3] Genevieve became a hurricane at 18:00 UTC on July 8 and a major hurricane, with peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h), 48 hours later.[4] Its forward trajectory soon brought the cyclone over colder waters, and the cyclone began to weaken. It curved north and made landfall about 90 mi (140 km) northwest of Cabo San Lucas, Baja California Sur, at 09:00 UTC on July 14, possessing 35 mph (56 km/h) winds by that point.[3] Genevieve transitioned into an extratropical cyclone three hours later before dissipating.[4]

Tropical Storm Hernan

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 27 – August 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical depression formed well south of Baja California Sur at 12:00 UTC on July 27. The cyclone moved west-northwest and then west, becoming Tropical Storm Hernan by 00:00 UTC on July 28. Unlike previous storms before it, Hernan encountered a less conducive environment of cool waters and wind shear.[3] It reached peak winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) on July 29, thus ending a string of East Pacific hurricanes. Hernan slowly succumbed to hostile conditions and dissipated after 00:00 UTC on August 1.[4]

Hurricane Iselle

edit| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 3 – August 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical disturbance drifted into the Gulf of Tehuantepec on August 3 and organized into a tropical depression around 18:00 UTC that day.[4] A potent upper-level trough dug southward into the coastal waters of California, creating a steering pattern that shunted the system northwest.[3] The depression intensified into a tropical storm 24 hours after formation, a hurricane by 06:00 UTC on August 6, and a major hurricane around 12:00 UTC on August 8. Six hours later, Iselle became a Category 4 cyclone with winds of 130 mph (210 km/h).[4] The system soon encountered ocean waters of 72–75 °F (22–24 °C) and weakened to the west of Baja California,[3] dissipating after 12:00 UTC on August 12.[4]

As the cyclone passed offshore, small craft warnings were enacted along the Mexico coastline.[6] Some street flooding was reported in Acapulco, Guerrero.[7] Farther north in western Texas, moisture from Iselle collided with cooler air from the north, causing thunderstorms and heavy rainfall. Up to 1.75 in (44 mm) fell in El Paso. Flash flood watches had been hoisted across several counties, and minor street flooding was reported in both El Paso and Juarez. Some mountain roads were impassable. A girl was killed when her normally dry home in a creekbed was overwhelmed by a flood. One person was also injured by lightning.[8] At beaches in Orange County, California, waves up to 13 ft (4.0 m) necessitated numerous lifeguard rescues. Some 385 rescues occurred in Newport Beach, while an additional 50 people were saved at San Clemente; rescues more than tripled the average at Huntington Beach.[9]

Tropical Storm Julio

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 15 – August 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

At 00:00 UTC on August 15,[4] a new tropical depression formed south of Acapulco. High pressure, extending across Mexico from the Gulf of Mexico, directed the system west-northwest.[3] It strengthened into Tropical Storm Julio eighteen hours later and soon peaked with winds of 60 mph (97 km/h).[4] An expansive upper-level outflow setup was disrupted by an increase in wind shear, which caused Julio to weaken despite warm ocean waters. The center dissipated about halfway between Socorro Island and Cabo Corrientes, Jalisco, after 12:00 UTC on August 20.[3][4]

Hurricane Keli

edit| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 16 – August 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); |

In mid-August, an area of disturbed weather persisted within the ITCZ across several days. It definitively organized into Tropical Depression One-C around 18:00 UTC on August 16, becoming Tropical Storm Keli six hours later.[5] The storm moved well to the south of the Hawaiian Islands, but it intensified rapidly on a course toward Johnston Atoll.[5] Keli became a hurricane around 06:00 UTC on August 8 and a major hurricane, with peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h),[4] when a reconnaissance aircraft intercepted it about 48 hours later. A nearby upper-level trough began to shear Keli, directing its convection to the north; low-level flow, meanwhile, forced the storm's actual center westward. The system passed about 70 mi (110 km) southwest of Johnston Atoll, where an evacuation had been ordered. About 1 in (25 mm) of rainfall and wind gusts to 39 mph (63 km/h) were recorded there.[5] The system dissipated after 00:00 UTC on August 22.[4]

Tropical Storm Kenna

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 16 – August 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

An area of disturbed weather crossed Panama on August 7. It moved on a persistent westerly course under ridging that extended from California to the Hawaiian Islands.[3] The system organized into a tropical depression over the far western reaches of the East Pacific basin around 18:00 UTC on August 16. Six hours later, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Kenna.[4] On August 18, the cyclone crossed into the Central Pacific, attaining maximum winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) as estimated by a reconnaissance aircraft despite a generally disheveled presentation on satellite imagery.[5] Gradual weakening occurred thereafter, and Kenna degenerated to a remnant low after 18:00 UTC on August 21.[4] The remnants of the cyclone curved northwest and moved across the Big Island of Hawaii, producing rainfall accumulations of 6–8 in (150–200 mm) across its windward districts. These rains were beneficial during an ongoing drought.[5]

Tropical Storm Lala

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 23 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); |

An area of vigorous thunderstorm activity developed within the ITCZ over the open East Pacific on August 21. It moved west-northwest and acquired a well-defined circulation,[3] thus becoming a tropical depression around 18:00 UTC on August 23. The system crossed into the Central Pacific early on August 26.[4] Four days later, a reconnaissance aircraft intercepted the cyclone for the first time, finding winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) and supporting the system's upgrade to Tropical Storm Lala. Lala tracked to the south of the Hawaiian Islands and Johnston Atoll, dissipating after 18:00 UTC on September 2.[4][5]

Hurricane Lowell

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 26 – August 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical wave entered the Gulf of Tehuantepec on August 22. The system moved rapidly westward amid a favorable combination of low wind shear and warm ocean waters.[3] It became a tropical depression around 06:00 UTC on August 26, coalesced into Tropical Storm Lowell twelve hours later, and intensified into a hurricane by 18:00 UTC on August 27. The next day, Lowell acquired peak winds of 85 mph (137 km/h).[4] It later encountered cooler waters,[3] which caused the cyclone to dissipate after 06:00 UTC on August 30.[4] As a hurricane, Lowell clipped the 350 ft (110 m) freighter Blue Falcon, cracking its bow and forcing the rescue of 23 crewmembers.[10]

Tropical Storm Moke

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 4 (Entered basin) – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); |

In August 1984, expansive ridging persisted across the North Pacific while a series of cold-core lows wandered underneath. One such upper low persisted near the International Date Line in close vicinity to Midway Island—as evidenced by low temperatures aloft in radiosondes released there—and developed a surface circulation, being declared as a tropical depression by the Japan Meteorological Agency on September 2.[11] While the lack of satellite coverage made tracking the system difficult,[5] forecasters believe it organized into Tropical Storm Moke by 06:00 UTC on September 4.[4] Spotty satellite imagery showed a well-organized storm with hints of an eye. Moke moved north-northeast in advance of an upper-level trough, which soon imparted shear and caused rapid weakening.[5] The system transitioned back into an extratropical cyclone after 00:00 UTC on September 5.[4][5] As a tropical system, Moke produced wind gusts up to 35 mph (56 km/h) on Midway Island and slightly more severe conditions on Kure Atoll.[5]

Hurricane Marie

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 5 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical depression formed south of Manzanillo, Colima, at 12:00 UTC on September 5. It became Tropical Storm Marie six hours later and further intensified into a hurricane by 00:00 UTC on September 7. Marie northwest over warm waters and reached peak winds of 90 mph (140 km/h) on September 8.[4] As the storm bypassed Baja California to the west, it encountered colder waters and began to weaken. A reconnaissance aircraft mission into the storm later that day measured a large, poorly-defined 58 mi (93 km) diameter eye. Subsequent investigations of Marie found a storm becoming increasingly disheveled over 68 °F (20 °C) waters;[3] it dissipated after 00:00 UTC on September 11.[4]

Rough surf up to 10 ft (3.0 m) was reported at Huntington Beach, California, where a 50-year-old man drowned. Lifeguards performed more than 30 rescues there.[12] Humidity from the storm spawned swift-moving thunderstorms across southern California. The roof of a bowling alley collapsed, submerging bowling lanes in 3 ft (0.91 m) of water. Floods inundated roads, including U.S. Route 95 in California, and frequent lightning caused power outages to dozen of homes.[13]

Hurricane Norbert

edit| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 14 – September 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); |

At 18:00 UTC on September 14, the season's next tropical depression developed southwest of Baja California. It strengthened into Tropical Storm Norbert six hours later.[4] Embedded within weak steering flow, the newly named cyclone wound its way north, particularly after upper-level trough developed over the Rocky Mountains.[3] Norbert steadily intensified, organizing into a hurricane around 12:00 UTC on September 16 and a major hurricane by 00:00 UTC on September 18. The potent storm fluctuated between Category 3–4 intensity for many days thereafter, reaching peak winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) on four separate occasions.[4] On September 23, a reconnaissance aircraft intercepted Norbert and its well-defined eye, marking the first time that the inner core of a hurricane was mapped three-dimensionally.[14] Between 00:00–06:00 UTC on September 26, Norbert made landfall near Punta Abreojos as a tropical storm.[4] While the storm is officially recognized as dissipating over Baja California,[4] forecasters in Arizona expressed high confidence that it remained a tropical cyclone into that state.[15]

In the small fishing communities of Punta Abreojos and La Bocana along the coastline of Baja California Sur, 90 percent of structures were demolished.[16] One person was killed, one person was reported missing, and more than $140 million in damage occurred there.[17] The remnants of the cyclone produced sporadic rainfall across Mexico.[18] Slightly higher accumulations were reported in Arizona, where flash flood watches were hoisted across several counties and some school districts released students early owing to those concerns.[19][20]: 1 Accumulations peaked at 4.15 in (105 mm) on Kitt Peak in Arizona.[15] Normally dry roadways were inundated with runoff, and three people were rescued from a rain-filled streambed.[20] About 50 roads were closed in Tucson and surrounding areas.[20]: 2 Sustained winds up to 30 mph (48 km/h) were observed in similar locales.[15]

Hurricane Odile

edit| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 17 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); |

At 18:00 UTC on September 17, a tropical depression formed to the south of Acapulco.[3] It developed into Tropical Storm Norbert six hours later and into a hurricane by 00:00 UTC on September 20.[4] The cyclone originally moved west-northwest and north under the influence of a ridge near Acapulco. However, that ridge shifted southwest while an upper-level trough progressed into northern Mexico, forcing Odile to the east.[3] The hurricane attained peak winds of 105 mph (169 km/h),[4] Category 2 intensity, early on September 22 to the east of nearby Hurricane Norbert. Another upper-level trough diving into Baja California caused Odile to quickly veer northwest, and it made landfall about 45 mi (72 km) northwest of Zihuatanejo, Guerrero, at 18:00 UTC on September 22,[3] harboring winds of 60 mph (97 km/h). The system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and dissipated after six hours.[4]

Odile produced copious amounts of rainfall across Southern Mexico, including a maximum accumulation of 24.73 in (628 mm) in Costa Azul/Acapulco.[21] Between the Zihuatanejo and Acapulco airports, some 87 commercial flights were cancelled, including 50 charter flights. Hotels were deserted across typically busy tourist areas.[22] The heavy precipitation inundated roadways and filtered into the lobby of the Zihuatanejo airport.[23] Throughout the state of Guerrero, 44 riverbank and mountain communities were isolated, encompassing some 30,000 residents. The cyclone overturned a barge on the Atoyac River, resulting in the drownings of 18 passengers and 3 crewmembers.[24] Odile compounded the effects of previous systems which in totality yielded Mexico's wettest year since 1978. Those floods damaged countless structures, severely affected crops, left thousands of residents displaced, and killed many people.[25]

Hurricane Polo

edit| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 26 – October 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); |

An area of disturbed weather entered the Gulf of Tehuantepec on September 24, organizing into a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC on September 26. The depression moved west-southwest initially, but it curved northwest after becoming Tropical Storm Polo around 18:00 UTC on September 28.[3] At 00:00 UTC on September 30, Polo became the season's final hurricane. Two days later, it became the season's last major hurricane with peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h).[4] The cyclone curved northeast ahead of an upper-level trough over Baja California, and that feature brought Polo into colder waters and higher wind shear. The system crossed Baja California Sur between 06:00–12:00 UTC on October 3 as a 35 mph (56 km/h) tropical depression.[3] It dissipated over the Gulf of California after 12:00 UTC.[4]

Moisture from the remnants of the storm streamed north into the Southwestern United States, prompting flash flood watches across Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Up to 2 in (51 mm) of rain was recorded in Reserve, New Mexico. Heavy rain caused rockslides in Utah west of Castle Dale.[26] Heavy rain across Colorado translated to snow in higher elevations, with advisories warning of the potential for 8 in (200 mm) accumulations.[27]

Tropical Storm Rachel

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 7 – October 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical disturbance crossed Costa Rica on October 4. It remained steady state for several days while moving west but ultimately organized into a tropical depression around 18:00 UTC on October 7. The depression encountered warm waters along its track,[3] which fueled its organization into Tropical Storm Rachel by 06:00 UTC on October 9. The next day, Rachel attained peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h).[4] A broad upper-level trough over Baja California steered the cyclone west-northwest into cooler waters, and it began to weaken.[3] Rachel maintained intensity as a tropical depression for many days before dissipating over the open East Pacific after 12:00 UTC on October 16.[4]

Tropical Storm Simon

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 31 – November 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); |

Tropical Depression Twenty-Three, the season's final tropical cyclone, formed in the Gulf of Tehuantepec around 00:00 UTC on October 31.[3][4] As high pressure centered over the Gulf of Mexico slid west, the newly designated system likewise followed a westerly course.[3] At 00:00 UTC on November 1, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Simon. The next day, it attained peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h).[4] Simon soon encountered increasingly cool waters and began to weaken,[3] dissipating over the open East Pacific after 00:00 UTC on November 8 and drawing the season to a close.[4]

Other systems

editOutside the purview of the official hurricane database, the Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center also documented several unofficial tropical depressions during the season. On June 29, a poorly organized area of convection formed south-southeast of the Gulf of Tehuantepec. It became a tropical depression on June 30 but failed to organize further owing to influence by Hurricane Elida to its west-northwest. It dissipated south of Acapulco on July 2. A fast-moving disturbance in the ITCZ developed on July 13 and separated from that feature, becoming a tropical depression on July 23. However, it dissipated over colder waters in the far western reaches of the East Pacific two days later. [3]

On September 11, another tropical depression formed over the Gulf of Tehuantepec. However, it was positioned on the south side of an upper-level trough extending from Texas into Mexico, and the shearing effects of that feature caused the cyclone to dissipate on September 22; its remnants continued inland about 50 mi (80 km) east of Salina Cruz. Three days later, a new tropical depression developed about 60 mi (97 km) west-southwest of Zihuatanejo. In spite of very warm ocean waters, the system struggled under the influence of Hurricane Norbert to the west and the close proximity of the Sierra Madre del Sur. It moved onshore about 35 mi (56 km) southeast of Manzanillo, Colima, at 02:00 UTC on September 15. On November 3, an area of convection formed northwest of Clipperton Island. It developed into a tropical depression on November 5 but did not intensify further as it met cooler waters. The system dissipated after just twelve hours.[3]

Storm names

editThe following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Pacific Ocean east of 140°W in 1984.[28] This was a new set of names, and every name used this season was used for the first time.[29] No names were retired from this list following the season, and it was next used (expanded to include "X", "Y", and "Z" names) for the 1990 season.[30]

|

|

|

For storms that form in the North Pacific from 140°W to the International Date Line, the names come from a series of four rotating lists. Names are used one after the other without regard to year, and when the bottom of one list is reached, the next named storm receives the name at the top of the next list.[28] Three named storms, listed below, formed in the central North Pacific in 1984. Named storms in the table above that crossed into the area during the year are noted (*).[5]

|

|

|

Season effects

editThis is a table of all of the tropical cyclones that formed in the 1984 Pacific hurricane season. It includes their name, duration, peak classification and intensities, areas affected, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1984 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alma | May 17–21 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Boris | May 28 – June 18 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Cristina | June 17–26 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Douglas | June 25 – July 6 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 939 | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Elida | June 28 – July 8 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Fausto | July 3–10 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Genevieve | July 7–14 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Hernan | July 27 – August 1 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Iselle | August 3–12 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | Unknown | Guerrero, California | Minimal | 1 | [3][8] | ||

| Julio | August 15–20 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Keli | August 16–22 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | Unknown | Johnston Atoll | None | None | [3] | ||

| Kenna | August 16–21 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | Unknown | Hawaiian Islands | None | None | [3] | ||

| Lala | August 23 – September 2 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Lowell | August 26–30 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Moke | September 4–5 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | Unknown | Midway Island, Kure Atoll | None | None | [3] | ||

| Marie | September 5–11 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | Unknown | California | Minimal | 1 | [3][12] | ||

| Norbert | September 14–26 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | Unknown | Baja California, Sonora, Arizona | $140 million | 1 | [3][17] | ||

| Odile | September 17–22 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | Unknown | Guerrero | Unknown | ≥21 | [3][24] | ||

| Polo | September 26 – October 3 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | Unknown | Southwestern United States | None | None | [3] | ||

| Rachel | October 7–16 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Simon | October 31 – November 8 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | Unknown | None | None | None | [3] | ||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 21 systems | May 17 – November 8 | 145 (230) | 939 | $140 million | ≥24 | |||||

See also

edit- List of Pacific hurricanes

- Pacific hurricane season

- 1984 Atlantic hurricane season

- 1984 Pacific typhoon season

- 1984 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- Australian cyclone seasons: 1983–84, 1984–85

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 1983–84, 1984–85

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1983–84, 1984–85

References

edit- ^ Hiroyuki Murakami; Gabriel A. Vecchi; Thomas L. Delworth; Andrew T. Wittenberg; Seth Underwood; Richard Gudgel; Xiaosong Yang; Liwei Jia; Fanrong Zeng; Karen Paffendorf; Wei Zhang (January 1, 2017). "Dominant Role of Subtropical Pacific Warming in Extreme Eastern Pacific Hurricane Seasons: 2015 and the Future". Journal of Climate. 30 (1): 251. Bibcode:2017JCli...30..243M. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0424.1. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ "Hurricanes: Frequently Asked Questions". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-30. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh Emil B. Gunther; R.L. Cross (August 1, 1985). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1984". Monthly Weather Review. 113 (8). Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center: 1393–1410. Bibcode:1985MWRv..113.1393G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1985)113<1393:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 26, 2024). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2023". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. A guide on how to read the database is available here. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tropical Cyclones 1984 (PDF) (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ "Small craft warning eased". San Angelo Standard-Times. Mazatlan, Mexico. August 10, 1984. p. 23. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hurricane". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Fort Worth, Texas. August 7, 1984. p. 7. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Storm looming in west". San Angelo Standard-Times. San Angelo, Texas. August 9, 1984. p. 1. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Storm — Surfer heaven is swimmer's nightmare". The Sacramento Bee. Vol. 256. Newport Beach, California. August 12, 1984. p. 40. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tug returns; no word on abandoned freighter". News-Pilot. Long Beach, California. September 4, 1984. p. 2. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kitamoto, Asanobu (1984-09-03). "Daily Weather Charts". National Institute of Informatics. Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ a b Barry S. Surman; Kristina Lindergren (September 10, 1984). "Clouds, Isolated Showers Provide Short Respite From the Heat". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. p. 48. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Art Wong (September 11, 1984). "Storm's remnants snap three-week heat wave". The San Bernardino Sun. San Bernardino, California. p. 1. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Marks, Frank D.; Houze, Robert A.; Gamache, John F. (1992). "Dual-Aircraft Investigation of the Inner Core of Hurricane Norbert. Part I: Kinematic Structure" (PDF). Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 49 (11): 919. Bibcode:1992JAtS...49..919M. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1992)049<0919:DAIOTI>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b c "Hurricane Norbert 1984". National Weather Service. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Tucson, Arizona. Archived from the original on 2022-01-30. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ "News from Mexico". Santa Maria Times. Santa Maria, California. September 30, 1984. p. 46. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Speedier cleanup ordered". Arizona Daily Star. Vol. 143, no. 279. La Paz, Baja California. Associated Press. September 30, 1984. p. 13. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hurricane Norbert - September 24–27, 1984". Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on 2022-01-30. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ Douglas Kreutz (September 26, 1984). "Heavy rains expected, but no major flooding". Tucson Citizen. Tucson, Arizona. p. 7. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Norbert tame; three rescued from wash". Tucson Citizen. Tucson, Arizona. September 27, 1984. p. 1. Retrieved January 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hurricane Odile - September 16-24, 1984". Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on 2022-01-30. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ "Tropical storm Odile buffets Mexico resort". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Zihuatanejo, Mexico. September 23, 1984. p. 14. Retrieved January 9, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Telescope". Independent Coast Observer. Vol. 16. Gualala, California. September 28, 1984. p. 12. Retrieved January 9, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Frederick Kiel (September 26, 1984). "Dateline: Mexico: Mexican stock market hits all time high". United Press International. Archived from the original on 2022-01-30. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ "Hurricanes, storms leave many homeless in Mexico". The Des Moines Register. Mexico City, Mexico. September 25, 1984. p. 27. Retrieved January 9, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Last of Hurricane Polo dumps rain on Southwest". Sioux City Journal. Sioux City, Iowa. Associated Press. October 4, 1984. p. 2. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rockies get snow advisory; rain on Plains". The San Bernardino County Sun. San Bernardino, California. Associated Press. October 5, 1984. p. 2. Retrieved January 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1984. pp. 3-6–7, 10–11. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Name History". Atlantic Tropical Weather Center. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1990. pp. 3-6–7. Retrieved January 15, 2024.