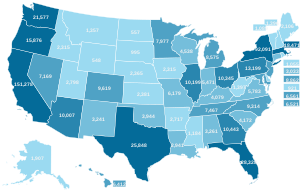

Homelessness in the United States has differing rates of prevalence by state. The total number of homeless people in the United States fluctuates and constantly changes, hence a comprehensive figure encompassing the entire nation is not issued, since counts from independent shelter providers and statistics managed by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development vary greatly. Federal HUD counts hover annually at around 500,000 people. Point-in-time counts are also vague measures of homeless populations and are not a precise and definitive indicator for the total number of cases, which may differ in both directions up or down. The most recent figure for 2019, was 567,715 individuals nationally that experienced homelessness at a point in time during this period.[3]

Homeless people may use shelters, or may sleep in cars, tents, on couches, or in other public places. Separate counts of sheltered people and unsheltered people are critical in understanding the homeless population. Each state has different laws, social services and medical policies, and other conditions which influence the number of homeless persons, and what services are available to homeless people in each state.

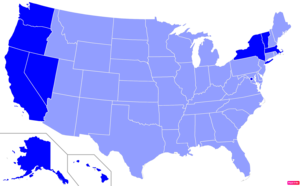

A 2022 study found that differences in per capita homelessness rates across the country are not due to mental illness, drug addiction, or poverty, but to differences in the cost of housing due largely to housing shortages, with West Coast cities including Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, and Los Angeles having homelessness rates five times that of areas with much lower housing costs, like Arkansas, West Virginia, and Detroit, even though the latter locations have high burdens of opioid addiction and poverty.[4][5][6][7]

The state by state counts of people listed below are derived from under-reported federal HUD statistics.

In June 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a ruling which permitted cities to ban homeless camps, thus making it possible to jail people for sleeping in areas such as public parks.[8][9]

Alaska

editMental illness in Alaska is a current epidemic that the state struggles to manage. The United States Interagency Council on Homelessness stated that as of January 2018, Alaska had an estimated 2,016 citizens experiencing homelessness on any given day while around 3,784 public school students experienced homelessness over the course of the year as well.[10] Within that niche group,[clarification needed] an average of 25–28% of these homeless are either moderately or severely affected by mental illness, according to Torrey[11] (2018) with the Mental Illness Policy Organization on studies done in 2015. Currently, At the state's flagship Alaska Psychiatric Institute, almost half the rooms are empty, a problem that has persisted for several years (Anchorage Daily News. 2018).[12]

To assess the situation of each individual physically and mentally, and consider the social disparity that they may also have issues with. Financially, having money problems is a stressful situation to any ‘normal’ individual, but to have financial troubles as someone with mental illnesses could be nearly life-threatening. Trying to find capable staff to handle the needs of the homeless mentally ill, when they are sent in for processing in the Alaska Jail system to keep them off of the streets, is hard to come by due to budgetary issues and finding the workforce for this field.

Alabama

editAlthough throughout the United States panhandling is discouraged, passive panhandling falls under First Amendment rights to free speech.[13] In Alabama the prohibition of aggressive panhandling and regulation of passive panhandling is controlled by individual cities, with many panhandlers being charged with loitering offenses.[14] Loitering for the purposes of begging and prostitution in Alabama is a criminal offense.[15] An issue for Alabamians is the proportion of panhandlers defined as vagrants, who contrary to their implications, are not homeless but accept the generosity of the community under this false pretense.[16]

As the cities decide ordinances for the control of panhandling, there is a variety of methods used across the state depending on the issues in each city. Many cities such as Mobile, Alabama have introduced a set of ordinances to prohibit panhandling in the "Downtown Visitors Domain" area, as well regulations for panhandlers in the rest of the city including disallowing; panhandling at night, physical contact while panhandling, panhandling in groups, and approaching those in queues or traffic.[17] These ordinances are an improvement on the previously vague prohibition of "begging".[17]

For those soliciting donations for charitable organizations, a permit must be obtained for the fundraising operation to be exempt from panhandling ordinances.[18] Panhandling in the Downtown Visitors Domain may result in fines and jail sentences for those involved.[19] Another effort to limit panhandling in Mobile is an initiative using donation meters through which people can donate money to approved charities in attempts to resolve the necessity of panhandling by providing disadvantaged citizens with resources. This method attempts to lessen the recurring arrest and release of the publicly intoxicated, who are often homeless or vagrant and participate in panhandling.[20]

An important concern for those in Alabama's capital city, Montgomery, is those who travel from other cities to panhandle, with a police report from November 2016 showing that most panhandlers in the area had travelled to the city for the purposes of begging.[21] In the city of Daphne, panhandling is prohibited within 25 feet of public roadways and violators are subject to fines,[22] while the cities of Gardendale and Vestavia Hills prevent all forms of panhandling on private and public property.[23][24] The city of Tuscaloosa prohibits all aggressive panhandling, as well as passive panhandling near banks and ATMs, towards people in parked or stopped vehicles and at public transport facilities.[25]

Alabama's most populous city, Birmingham has considered limitations on panhandling that disallow solicitation near banks and ATMs, with fines for infractions such as aggressive or intimidating behaviour.[26] Another concern for Birmingham is litter left behind in popular panhandling sites, especially for business owners in the downtown area.[27][28] In Birmingham, specifically asking for money is considered illegal panhandling.[29] The City Action Partnership (CAP) of Birmingham encourages civilians to report and discourage panhandlers throughout the city, especially under unlawful circumstances including panhandling using children, aggression, false information and panhandling while loitering as prohibited by City Ordinances.[30]

Within the city of Opelika it is considered a misdemeanour to present false or misleading information while panhandling, and there are requirements for panhandlers to possess a panhandling permit.[31] Threatening behaviours towards those solicited to are also considered misdemeanours and include; being too close, blocking the path of those approached, or panhandling in groups of two or more persons. Those previously charged with these offences in Opelika are not eligible for a panhandling permit within set time limits.[32] In this sense panhandling is a major issue in the region. Aggressive measures have been taken in order to address this issue.

Arizona

editThe state of Arizona has been very active in attempting to criminalize acts of panhandling. Measures have included arresting and jailing individuals caught in the act. Arizona's Revised Statutes title 13. Criminal Code 2905(a)(3) sought to ban begging from the state of Arizona, specifically in the area of being "present in a public place to beg, unless specifically authorized by law."[33] The city of Flagstaff took the policy a step further by implementing a practice of arresting, jailing and prosecuting individuals who are beg for money or food.[33]

In February 2013, Marlene Baldwin, a woman in her late 70s was arrested and jailed for asking a plain clothed officer for $1.25. Between June 2012 and May 2013 135 individuals were arrested under the law.[34] After criticism and a lawsuit from The American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona the policy was deemed unconstitutional, as it breached free speech rights granted by both federal and state constitutions. In his judgement, Judge Neil V. Wake declared the A.R.S 13-2905(a)(3) was void and prohibited any practices the city of Flagstaff has implemented that " interferes with, targets, cites, arrests, or prosecutes any person on the basis of their act(s) of peaceful begging in public areas."[33]

Despite this, the state of Arizona continued to pursue other ways to criminalize panhandling. Their response to Judge Wake's judgment was to criminalize "aggressive panhandling. The bill that passed into law in 2015 prohibits individuals from asking for money within 15-feet of an ATM or bank without prior permission from the property owner.[35] It prohibits "following the person being solicited in a manner that is intended or likely to cause a reasonable person to fear imminent bodily harm," or "obstructing the safe or free passage of the person being solicited."[35]

The city of Chandler has proposed a new bill that prevents panhandling along city streets justifying the law by citing safety concerns. The proposed laws would make it a civil traffic offence for an individual to be at a median strip for any purposes other than crossing the road.[36] Under the proposed law, the first violation would be treated as a civil traffic offence; however, a second violation within 24 months would be treated as a Class 1 misdemeanor citation in which an individual could be fined a maximum of $2500 and face up to six months in jail.[36] The State of Arizona continues to seek measures that would both limit panhandling but also satisfy the judgement made by Judge Neil V. Wake and the First Amendment.

Arkansas

editIn 2015, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development released a report detailing the decline of homelessness in Arkansas, but that the level of homeless veterans had increased. They found that 2,560 people were homeless in Arkansas in January 2015, and that 207 were veterans, an 83% increase in veteran homelessness since January 2009. Arkansas is one of only five states to have seen homelessness among veterans to increase by more than 100 people in that time. Of those five states, Arkansas had the largest number of homeless veterans. This is compared to nationwide, where homelessness among veterans has decreased by 35% since 2009.[37]

As of 2015, it was estimated that 1,334 of the homeless in Arkansas are youths. In Arkansas, the most common causes of homelessness are income issues and personal relationships. The median time spent homeless is 12 months, however 30% have been homeless for over two years.[38] Jon Woodward from the 7Hills shelter in Fayetteville, AR said "primarily the two largest groups of who's homeless in our region are families with children and veterans. And those are two groups that our community really does care about and can get behind supporting."[39] Despite this, shelters in Little Rock have struggled with insufficient funding and police harassment, resulting in reducing hours or closure.[40]

Under loitering laws, lingering or remaining in a public place with the intention to beg is prohibited in Arkansas.[41] However, in November 2016 in Little Rock, a judge ruled that this law banning begging was unconstitutional, and violated the First Amendment. The American Civil Liberties Union filed the case on behalf of Michael Rodgers, a disabled veteran, and Glynn Dilbeck, a homeless man who was arrested for holding up a sign asking for money to cover his daughter's medical expenses. ACLU were successful in their challenge, meaning that law enforcement officers will be prohibited from arresting or issuing citations to people for begging or panhandling.[42]

The loitering law has had a history of being abused by police officers in the state of Arkansas. For example, two homeless men reported separate incidents of having been kicked out of Little Rock Bus Station by police officers. Despite showing valid tickets that showed that their bus would arrive within 30 minutes, they were told they could not wait on the premises because they were loitering. In another incident, police officers told homeless people to leave a free public event or be subject to arrest for loitering in a park, although vendors at the event had encouraged the homeless to attend and take free samples of their merchandise. In 2005, police assembled an undercover taskforce to crack down on panhandling in the downtown Little Rock area, arresting 41 people.[40] 72% of the homeless report ever being arrested.[38]

California

editAbout 0.4% of Californians and people who live in the state (161,000) are homeless.

In 2017, California had an oversized share of the nation's homeless: 22%, for a state whose residents make up only 12% of the country's total population. The California State Auditor found in their April 2018 report Homelessness in California, that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development noted that "California had about 134,000 homeless individuals, which represented about 24 percent of the total homeless population in the nation”[43]

The California State Auditor is an independent government agency responsible for analyzing California economic activities and then issuing reports.[44] The Sacramento Bee notes that large cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco both attribute their increases in homeless to the housing shortage.[44] In 2017, homeless persons in California numbered 135,000 (a 15% increase from 2015).[45]

In June 2019, Los Angeles County officials reported over 58,000 homeless in the county.[46] Many of LA's homeless live in Downtown, Skid Row, Westlake, and Venice Beach.

San Francisco

editA 2023 study published by the University of California, San Francisco found that around 90% of the homeless population of California lost their housing while living in the state. The research also revealed that around half of the homeless population is over 50 years old, with black residents disproportionally represented, that the majority of the homeless population want to find housing, and the high cost of housing was the greatest obstacle to exiting homelessness.[47]

San Francisco and the general Bay Area has tens of thousands of homeless. SF has between 7–10,000 homeless people.

In June 2024, The Supreme Court issued a 6-3 ruling which reversed a California appeals court decision preventing cities from criminal homeless camps and sleeping in public areas.[8]

Colorado

editHomelessness is a growing problem in the State of Colorado, as the state's population grows. 0.2–0.3% of Coloradans or people who live there are homeless on a given night.

Denver and Colorado Springs have the largest homeless communities.

In April 2012,[48] Denver enacted the Urban Camping Ban due to the occupy Denver protest and the number of homeless on the 16th Street Mall. Mayor Michael Hancock and City Council passed the urban camping ban which prohibited individuals from sleeping in public places with a blanket over them or something between them and the ground.

Colorado was ranked 7th in 2017 for largest homeless veteran count as well as 8th in the country out of 48 major metropolitan cities for homeless individuals.[49]

The Right to Rest Act was introduced to Colorado, as well as Oregon and California, that changed the way the city treated unsheltered citizens. This piece of legislature called the Right to Rest Act was introduced in 2015 and attempted to offer homeless rights to sleep on public property like parks and sidewalks.[50]

The homeless population over the last four years within the state of Colorado has remained fairly constant. According to HUD's PIT Count (2018)[51] there are 10,857 people who are currently homeless within the state of Colorado.[52]

Connecticut

editAs of 2022 there were roughly 2,930 homeless people in Connecticut, an increase from 2,594 the previous year. In June 2023, House Bill 6601 was passed in the House and Senate, which declares homelessness a public health emergency.[53][54]

Delaware

editA survey in 2023 estimated there was about 1,255 homeless people in Delaware.[55]

Florida

editBecause of its warm weather, Florida is a favorable destination for the homeless.[56]

As of January 2017, there are an estimated 32,190 homeless individuals in Florida. Of this high number, 2,846 are family households, 2,019 are unaccompanied young adults (aged 18–24), 2,817 are veterans, and an estimated 5,615 are individuals experiencing chronic homelessness.[57] Due to the eviction moratorium ending during the early fall of 2021, the number of homeless individuals and families may increase. According to a January 2020 count, this figure was 27,487 on any given day, a decrease from previous years. However, this figure could likely increase due to the COVID-19 eviction moratoriums in the United States that started in September and October 2021.[58]

Pinellas County has one of the highest concentrations of any Florida county, at nearly 0.3% with nearly 3,000 homeless people and a population in general of almost one million. It is second next to Miami-Dade County's homeless population at 4,235, but this is due to a higher general population (6 million; 0.08%) and still a lower prevalence closer to Florida and the U.S.'s average between 0.1 and 0.2%.[59]

Various cities in Florida have laws against aggressive panhandling and general panhandling that could result in fines or demands to leave, as well as sleeping on benches or parks.

Georgia

editThe rise of neoliberal governance has dramatically changed the way that people who are homeless in heavily populated cities are dealt with and treated around the United States.[60] Neoliberal governance is the promotion of human advancement through economic growth. The most accepted idea of achieving this is by pushing towards a free market economy which thrives off of not having much government or state participation.[61]

In the 1970s and 1980s, Atlanta, Georgia was one of these cities where businesses were very active in their efforts to decrease homelessness in the spirit of this idea. The Central Atlanta Progress (CAP) was one of the most notable voices in Atlanta promoting these sort of initiatives. For example, their first major initiative was to criminalize homelessness. They saw the homeless population as a threat to public safety. Their efforts were met with conflicted responses from police and Georgian citizens due to the large size and demographic makeup of the homeless population in Atlanta. The majority of the homeless were black males.[61]

On top of that, Atlanta's first black mayor, Maynard Jackson, had been recently elected into office. Having elected a black male into office, the topic of race and politics was prominent in the minds of many Georgian citizens.[61] The idea to criminalize homelessness looked bad in the eyes of these citizens and created a lot of skepticism about the CAP's true purpose. Participation was not met in the way the CAP had hoped for.

Since the 1970s and 1980s attempts to combat homelessness have continued not just from businesses but from the government level as well.[62] In 1996 to prepare for hosting the Olympic games, Fulton County provided the homeless people in the area with the opportunity to leave the town as long as they could provide proof of either a family or a job waiting for them at their choice of destination. Fulton County would then give them a one way bus ticket provided that the recipient signed a document agreeing not to return to Atlanta.[63]

While it is unclear how many people took this offer to leave the city for free, it is estimated that thousands of the homeless population in Atlanta did take this one-way ticket. For the ones that did not leave, around 9,000 homeless persons were arrested for activities such as[64] trespassing,[65] disorderly conduct, panhandling, and[66] urban camping. Urban camping is the use of public or city owned space to sleep or to protect one's personal belongings. For example, the use of a tent underneath a bridge in order to serve as a living space is prohibited.

Action towards panhandling has also been seen from the government.[67] Many downtown cities around the United States have tried to combat panhandlers by prohibiting panhandling at certain locations as well as restricting the time periods that it is allowed. In Georgia, Atlanta was proactive with this idea by banning panhandling in what is known as the "tourist triangle" in August 2005.[68] Another ban prohibited panhandling within 15 feet of common public places such as ATM's and train stations. Violations are punished with either a fine or imprisonment.[69]

In 2012, the city of Atlanta created an anti-panhandling law which criminalizes aggressive panhandling. Aggressive panhandling is defined as any form of gestures or intense intervention for the sake of retrieving monetary substance.[69] This includes blocking the path of a bystander, following a bystander, using harsh language directed at a bystander, or any other indications that could be perceived as a threat by the person it is directed at. Violations are punished based on the number of offenses with the third offense being the highest. The third offense and all future offenses beyond that will result in a minimum of 90 days in jail. A second offense will result in 30 days of jail time while the first offense results in up to 30 days of community service.[70]

The policies that Atlanta has put in place were very similar to the ones that Athens, Georgia currently has. Failing to adhere to the law could result in jail time or community service. Athens-Clarke County added the possibility for a fine to be paid instead of serving prison time or participating in community service.

Hawaii

editIn Honolulu, aggressive measures have been taken to remove the homeless from popular tourist spots such as Waikiki and Chinatown. Measures include criminalizing sitting or lying on sidewalks and transportation of homeless to the mainland.[71] Section 14-75 of the Hawaii County Code gives that soliciting for money in an aggressive manner is illegal, with "aggressive" behaviors defined as those that cause fear, following, touching, blocking or using threatening gestures in the process of panhandling.[72] The citation penalty is a $25 fine and may include a term of imprisonment.[73]

Maria Foscarinis, executive director of the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, says that panhandling restrictions are a result of gentrification coupled with Hawaii's dependence on tourism.[74] In 2013 alone, tourism in Hawaii generated $14.5 billion, which averaged $39 million per day.[75] Hawaiian locals and business operators such as Dave Moskowitz agree with these restraints, arguing that panhandling is bad for tourism.[73]

Police in Hawaii state that panhandling is not a prominent issue, nor is it prioritized.[76] Legally, ethically and practically, it is difficult for police to enforce strict panhandling laws at all times, thus police discretion plays a vital role in determining who is cited and how many citations are given.

For the panhandling population who are cited, there is a general feeling of indifference or disregard, including refusal to pay fines.[71] A number of studies indicate that the average panhandler is an unmarried, unemployed male in his 30s to 40s, often with drug/alcohol problems, a lack of social support and laborer's skills.[76] These factors are likely to affect the poor perception of these laws in the panhandling population.

Social justice advocates and non-governmental organizations will argue that this approach is therefore counterintuitive. They argue that panhandling laws violate free speech, criminalize homelessness and remove an essential part of destitute people's lives. Doran Porter, executive director of the Affordable Housing and Homeless Alliance, argues that these laws merely deal with the symptoms of homelessness rather than fixing the problem.[73]

Courts clarify whether the laws that restrict panhandling are constitutionally valid. In 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union of Hawaii foundation (ACLUH) paired with Davis Levin Livingston Law Firm to represent Justin Guy in suit against the Hawaii County. Guy's lawyers argued that prohibiting their client from holding up a sign that read 'Homeless Please Help' offended his First Amendment right to freedom of speech.[77] Matthew Winter, a lawyer on the case, made reference to political candidates, who are lawfully able to hold signs, to contrast against the inability of the poor to hold up signs asking for help.[77] The court ruled in Guy's favour, which led to an award of $80,000 compensation and repeal of subsections 14–74, 14–75, 15–9, 15–20, 15–21, 15–35 and 15–37 of the Hawaii County Code. In a statement, Guy emphasized the need for the State of Hawaii to treat the homeless with the same dignity as the general population.[77]

The future of panhandling laws in Hawaii is reliant on legislators and their perception of panhandling's impact on tourism. By utilizing aggressive political language, such as 'the war on homelessness' and 'emergency state,' Hawaiian politics will continue to criminalize the behaviors of destitute populations. On the other hand, with pressure from state/federal departments and non-governmental organizations, restrictions on panhandling laws may be possible. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, for example, has stated that it would not provide homeless assistance funds to states that criminalize homelessness.[71] Given that Hawaii has one of the US's largest growing homeless populations (between 2007 and 2016, Hawaii saw a 30.5% increase in homelessness), it is in a poor position to reject federal funding and assistance from non-governmental organizations.[78]

Idaho

editThis section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2023) |

Illinois

editThe city of Chicago, Illinois has gained a reputation as the city with the most homeless people, rivaling Los Angeles and New York City, although no statistical data have backed this up. The reputation stems primarily from the subjective number of beggars found on the streets, rather than any sort of objective statistical census data. In 2007, Chicago had far less homeless people per capita than peers New York, and Los Angeles, or other major cities such as Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Boston, among others, with only 5,922 homeless recorded in a one night count.[79]

A 2019 study by the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless found that among Chicago's homeless population for 2017, 18,000 had college degrees and 13,000 were employed.[80]

Despite the challenges surrounding the search for objective data, a 2022 study led by University of Chicago Health Lab researchers Jackie Soo and Leoson Hoay uncovered significant costs associated with high users of the city's social services, including homelessness services. These costs were amplified within a particularly vulnerable group that consistently cycled across multiple services - specifically the homelessness system, hospital system, and criminal justice system.[81]

Indiana

editIn Indianapolis, Indiana, as many as 2,200 people are homeless on any given night, and as many as 15,000 individuals over the course of a year. Indianapolis is notable among cities of similar size for having only faith-based shelters, such as the century-old[82] Wheeler Mission. In 2001, Mayor Bart Peterson endorsed a 10-year plan, called the[83] Blueprint to End Homelessness, and made it one of his administration's top priorities. The plan's main goals are for more affordable housing units, employment opportunities, and support services. The Blueprint notwithstanding, Indianapolis has criminalized aspects of homelessness, such as making panhandling a misdemeanor. The City-County Council has twice, in April 2002, and August 2005, denied the zoning necessary to open a new shelter for homeless women.[84]

Iowa

editHomelessness in Iowa is a significant issue. In 2015, 12,918 Iowans were homeless and 'served by emergency shelters, transitional housing, rapid rehousing or street outreach projects'.[85] Another 8,174 Iowans were at risk of being homeless and lived in supportive housing or were involved in street outreach projects.[85] The actual number of homeless Iowans is likely to be substantially greater, as these figures only account for those who sought help. Homelessness is particularly problematic in Iowa City, as there is only one shelter in the city to cater for its large homeless population.[86] Those who have been abusing substances are prohibited from using this shelter, thus excluding a large proportion of homeless people.[87]

Panhandling has become an increasingly significant problem in Iowa. There is much controversy surrounding how best to deal with this widespread issue. Debate has focused on the best way to balance compassion, free speech and public safety.[88] Iowan cities have struggled with finding the balance between avoiding criminalising poverty, while at the same time not encouraging begging, particularly that which is aggressive. There has also been widespread concern about the legitimacy of panhandlers and the significant amount of money that some are making. Cedar Rapids panhandler, Dawn, admitted that she has come across many illegitimate panhandlers. These include people who already have access to housing and financial assistance, and even some who pretend to be disabled or to be a veteran.[89]

A famous incident in Muscatine, Iowa, photos of which went viral, provides a prime example of the tensions that exist around the legitimacy of panhandlers. In December 2015, two young boys were panhandling, holding signs which read 'broke and hungry please'.[90] Pothoff, who worked nearby, offered the boys a job. The boys stated that they were 'not from around here', smirked and walked away. Pothoff then decided to join the boys on the side of the road, holding up his own sign, which read 'Offered these guys a job, they said no, don't give them money'.

Following the Supreme Court case, United States v Kokinda, 497 U.S. 720, 725 (1990), the right to beg for money is protected speech under the First Amendment.[91] Therefore, panhandling cannot be entirely prohibited. However, as per Ward v Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781, 791 (1989), US cities may enact 'reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions' which are narrowly drafted to 'serve a significant governmental interest' and also allow for this speech to occur in an alternative setting.[91]

This has led to a trend amongst many Iowan cities of enacting ordinances which control and restrict panhandling. In Bettendorf, aggressive panhandling, panhandling on a travelled portion of a roadway and soliciting on a bus, bus stop, within 15 feet of an automated teller machine or on Interstate 74 exit ramps between certain hours of the day are all prohibited.[92] A panhandling licence is required and this can be revoked for 6 months if any of these regulations are breached, in addition to a fine or incarceration.[93] Bettendorf grants panhandling licences for free, however licences must be renewed every 6 months and candidates must undergo a police check.[94]

Similarly, in Davenport, aggressive panhandling, soliciting within 20 feet of an automated teller machine or bank entrance, or on a roadway or median of a roadway are prohibited.[93] Police Chief Paul Sirorski admitted that the ordinance can be difficult to enforce and that the number of complaints concerning panhandlers in Davenport is increasing.[95] In light of community concerns, Davenport is set to review the ordinance.[96]

Iowa City has similar ordinances and has installed special purple parking meters which are used to fund homeless organizations.[97] The aim is to encourage people to give money to homeless programs through parking fees, rather than directly to beggars. However, some argue that it is better to donate money to panhandlers than to organizations as you can be sure that the money is going directly to the person without any loss through administrative costs.[98]

As Cedar Rapids currently has no ordinance controlling panhandling, there has been an increase in the number of panhandlers.[99] Cedar Rapids has also seen an increase in the number of complaints concerning panhandlers.[99] This has led to consideration of the introduction of an ordinance that would prohibit panhandling in certain areas. The ordinance also includes plans for police to be able to give resource cards to panhandlers. These cards provide a list of resources which provide housing, food and financial assistance.

Councils claim that these ordinances are necessary to ensure public safety and prevent traffic accidents. Other rationales behind these laws include 'to improve the image of the city to tourists, businesses and other potential investors' and to reflect the growing "compassion fatigue" of the city's middle and upper class after increasingly being exposed to widespread homelessness.[100] However, Saelinger (2006) argues that these laws '"criminalize" the very condition of being homeless'.[100] Saelinger (2006) also claims that through the implementation of these laws, governments have focused on making homelessness invisible, rather than working to eradicate it.[100] The aesthetics of cities has also influenced the enactment of these ordinances, with businesses complaining that panhandlers bother their customers and make them feel uncomfortable, in addition to ruining the image of the city.[97]

Kansas

editIn comparison with the US, Kansas continued to have an increasing level of homelessness until 2015. Between 2007 and 2015, homelessness across the US fell by 13 percent, while in Kansas it rose by more than 23 percent. Individuals predominantly fell victim to homelessness rather than families, generating this increase in homelessness.[101] This is in discord with Sedgwick County's reputation as one of the most successful counties in the US for providing shelter to homeless family members and individuals. Chronic homelessness was seen to be more prevalent and increasing as was the proportion of veterans subjected to sleeping on the streets.[101] However, Kansas currently holds approximately 0.5% of the total homelessness in the US, listing itself in the bottom third of all of the US states.[102]

Begging and associated crimes

editThere is much concern within Kansas regarding the legitimacy of begging and panhandling. For example, within Wichita alone, there are many reports of persons posing as homeless to make a quick income and fuel their addiction habits such as alcohol, drugs, and sex.[103] This has been seen to increase recently with the development of boutiques and shops that are drawing growing numbers of customers and tourists to the area. Residents have further complained that many whom are homeless are frequently choosing to bypass available services in order to maintain their lifestyle. This increase in 'untruthful' begging has resulted in further chronic homelessness, as those who are most genuinely in need are being sidelined by 'quick-fix intruders'.[103]

The consequences of begging and panhandling across Kansas is not uniform, it differs from county to county, with some counties choosing to acknowledge it as a crime and others rejecting its presence. Under Kansas' Wyandotte County code of ordinances, panhandling is deemed an unlawful act when it occurs in an aggressive manner.[104] The consequences of panhandling present as an unclassified misdemeanour, which under Wyandotte County law signifies that unless the penalty is otherwise stated, it will receive the same penalty as a Class C misdemeanour i.e., punishable by up to one month in jail and a fine of up to $500.[105] This is less severe in comparison to Wichita County whereby the act of begging is deemed as a crime of loitering and is penalized with a fine of up to $1,000, one year imprisonment, or both.[106]

Counties such as Shawnee County and Sedgwick differ, with Sedgwick County making no mention of such acts constituting crimes within its ordinance, Topeka follows suit. Such a scenario in Topeka occurred due to a 9–0 vote to defer action of panhandling, where a penalty of 179 days in jail and/or a fine up to $499 might have been applied if caught violating this ordinance.[107] This ordinance was only suspended indefinitely. If it is reviewed and passed, it may result in the banning of solicitation on private property unless prior permission has been granted from the property owner. Begging would not be affected and would remain legal.[108]

Topeka currently does hold laws against soliciting on public property, which have not been found to target the homeless, rather targeting many backpackers instead. According to Topeka law, it is illegal to solicit funds, rides, or contributions along roadways, meaning that persons whom present cardboard signs asking for lifts throughout the city can be liable to penalties.[109] Such a law has stemmed from the high prevalence of scams in the area, such as men saying they have mechanical issues with their cars and women citing domestic abuse and the need for funds to stay at a hotel, which has forced a public awareness and therefore campaigns in the area.[109]

Kansas has a variety of services available to those who encounter panhandlers with organizations such as Downtown Wichita[110] in association with the Wichita police, creating information on methods to stop panhandling. This has been developed in the mode of a myriad of pamphlets regarding available services for the homeless which can be printed off and distributed by businesses when they encounter persons panhandling or begging.[103] Such services often report back to the Homeless Outreach Team in an attempt to reduce the prevalence of homelessness in the long-term.[111]

Persons encountering panhandlers and beggars in Kansas, if unable to politely refuse, are encouraged to contact 911.[103][111]

Kentucky

editMany city and counties within the United States have enacted ordinances to limit or ban panhandling.[112] However, the legality of such laws has recently come under scrutiny, being challenged as a violation of individuals first amendment rights.[113] The first amendment states that "Congress shall make no law ... prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech."[114] It is therefore argued that stopping someone from asking for help from their fellow citizens is impeding on their right to free speech.

Panhandling laws differ throughout the state of Kentucky. In the city of Louisville, for example, it is an offence to panhandle in certain locations including: within 20 feet of a bus stop or ATM, in a crosswalk/ street, or anywhere that may be impeding others.[115] The ordinance places a strong emphasis on aggressive panhandling which had become a prominent issue within Louisville.[115] These municipal laws are one of the many that have recently come under scrutiny, being challenged as unconstitutional under first amendment rights.[113][116] In October 2016, a judge of the Jefferson Court District ruled against the laws, deeming them to be unconstitutional.[117] This decision is currently being reviewed by the Kentucky Supreme Court.[117]

In contrast, the city of Ashland, Kentucky has not come under scrutiny as their ordinance is less comprehensive and therefore less likely to impede individuals rights.[118] However, recently the ordinance was amended to further crack down on the act of panhandling, adding an amendment to stop panhandlers from walking out into traffic, in an attempt to keep both beggars and the public safe.[118]

Panhandling laws are often controversial as they are generally welcomed by the public, who can feel harassed.[119] However, it is also argued that they are disadvantaging the homeless and those in need.[119] As an attorney of the UCLA states, panhandling laws are "misdirected" and their purpose is to try and hide the problem of homelessness.[120]

In 2017, there were 4,538 reported homeless people in the state of Kentucky (0.10% of the population), which is consistent with rates of homelessness in many of Kentucky's neighboring states including Tennessee and Ohio.[121] This number of homeless in Kentucky has declined since 2014.[121] The Kentucky Interagency Council on Homelessness is working towards an end to homelessness, their mission; to end homelessness across the state of Kentucky, with clear outlined goals and strategies on how this is going to be achieved.[122] One of their main goals is to assist local municipalities to end homelessness within the state.[122]

The director for Homeless Prevention and Intervention in Kentucky, Charlie Lanter, says that in regards to panhandling, "if they're successful, then they have no incentive to go to a shelter or to go somewhere for food, or whatever their particular needs are ..."[123] which limits the organizations ability to assist the individual off the streets. In particular, the city of Owensber has had support from its homeless shelters in protecting panhandler's rights on the streets, for example, Harry Pedigo, the director of St. Benedicts Homeless Shelter in Kentucky wants local panhandlers to know that the homeless organizations are there to help and not judge their situation.[124]

Louisiana

editBegging, panhandling and homelessness have been prevalent issues for the state of Louisiana for some time, and correlate closely with its poverty rates. Particularly since the disastrous Hurricane Katrina, which hit many Southern American states in 2005, poverty has maintained at a high level[125] The hurricane led to 1,577 deaths in Louisiana alone, with $13 billion invested in flood insurance aid.[125]

Hurricane Katrina had devastating physical, environmental, and socio-economic impacts on Louisiana. Much of Louisiana, and New Orleans in particular, is made up of African-African, elderly and veteran populations, many of whom were plunged into further poverty once their houses were damaged by floods[126] As a result, begging and panhandling in Louisiana is not just a matter of economics, but also of gender, race and age.[126] Louisiana remains the third most impoverished state in the United States, with nearly 1 in 5 people living in poverty.[127]

Begging and panhandling is now illegal in the state of Louisiana. Bill HB115 was passed first through the Louisiana Legislative House in 2014, and approved by the Senate in 2015.[128] Through the criminalization of begging, offenders can now be given fines of approximately $200, or alternatively sentenced to up to 6 months in jail.[128] The bill specifically targets homeless populations in Louisiana, and applies to prostitution, hitchhikers and the general solicitation of money.[129]

Supporters of the Bill hope that the criminalization of begging will lead to fewer homeless and poor people on the streets[128] Louisiana State Representative Austin Badone, the creator of the begging and panhandling bill, suggests that many of these people are not actually in need, and described the process of begging as a "racket."[128] Those opposed to the criminalization of begging and panhandling maintain that the law is unconstitutional, as they view begging under the category of Freedom of Speech.[130]

As a result, HB 115 has sparked social and political debate since its administration, as many argue that begging is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.[131] Initially, this was said to only apply to non-aggressive forms of panhandling or begging, which do not include any use of force or threats.[131] However, the criminalization of all begging in Louisiana has called into question whether or not the bill breaches the First Amendment right.

Because of these claims, Louisiana has taken steps to showcase that the First Amendment is being protected. The city of Slidell, Louisiana voted in July 2016 to implement permits for beggars and homeless people.[132] This would legally allow begging and panhandling in certain outlined areas. If their application is approved, this permit would be valid for one year, and would be required to be displayed during panhandling and begging[132] The permit can also be denied if the applicant has previously been charged with misdemeanours such as harassment or other begging-related offences.[133] Enforcement is set to begin by local Slidell authorities in November 2016.[133]

Maine

editThere are over 4,000 homeless people in Maine.

Maryland

editIn 2015, it was estimated that each year over 50,000 people experience homelessness in Maryland.[134] Although Maryland is one of the nation's wealthiest states, over 50% of impoverished Marylanders live in "deep poverty", meaning that their annual income is less than half of the federally defined poverty level.[134] Homelessness in Maryland increased by 7 percent between 2014 and 2015 according to statistics released by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development.[135]

Begging and associated crimes in Maryland

editPanhandling in Maryland is widely protected under the First Amendment,[136] provided that the act does not include conduct which 'harasses, menaces, intimidates, impedes traffic or otherwise causes harm'.[137][138] The president of the nonpartisan First Amendment Center has stated that any legislation prohibiting the act of begging violates the constitution by "limiting a citizen's right to ask for help".[139] In 1994, Baltimore City enacted a zero-tolerance arrest policy to counter rising violent crime rates, prompting a push to reclaim public spaces by targeting beggars and homeless persons.[140] This resulted in the case of Patton v. Baltimore City (1994), where zero-tolerance arrest policies to reclaim public spaces were ruled to be unconstitutional, due to violation of the homeless' First Amendment right to freedom of association.[140]

Traffic hazards due to roadside solicitation have been identified as a cause of concern throughout Maryland, generating various attempts by legal officials to regulate panhandling in high traffic areas.[138] As a result, solicitation or panhandling is banned on or beside state roads under state law.[138] A statewide ban on panhandling and vending at all highway intersections was proposed in 2001, but was later revised to apply only to Charles County.[141]

In 2006, the Anne Arundel County Council enacted a ban on panhandling by children under 18 years old.[142] In April 2007, the Maryland General Assembly passed a bill banning panhandling beside and on Anne Arundel County roadways, as well as prohibiting the display of political signs or advertising messages on any public roadways.[142] The American Civil Liberties Union have consistently opposed solicitation bans, due to concerns that legislation may hinder the fundraising efforts of legitimate organizations.[142] A bill has since passed the House of Delegates in 2016, allowing the act of panhandling by firefighters and non-profit groups, pending their successful completion of traffic safety courses.[143]

In late 2011, legislation was proposed in Montgomery County which would require panhandlers to seek permits in order to engage in roadside solicitation, but this proposition was heavily scrutinized due to concerns that panhandling permits could constitute a breach of the First Amendment.[138] In September 2013, Montgomery County leaders announced a plan to instead purge panhandling from busy streets by encouraging citizens to donate money to not-for-profit shelters and food banks, rather than directly donating to panhandling persons.[144]

In 2012, Allegany County imposed narrow restrictions on panhandling, allowing only one day permit per person per year for roadside solicitations.[145] Other areas of Maryland with similar permit provisions include Cecil, Frederick and Baltimore counties.[145] In 2012, certain panhandling ordinances within Frederick County revived First Amendment debates after undercover police officers donated money to begging persons and subsequently arrested them on panhandling charges.[146] Frederick County police allegedly responded by indicating that their initiative in panhandling arrests was in response to reported 'quality of life' issues.[146]

In early 2013, legislation to ban the act of panhandling in commercial districts within Baltimore was put forward, but was met with backlash by a mass of protesters chanting "homes not handcuffs".[147] A revised bill was proposed in November, stipulating that panhandling would be prohibited only within 10 feet of outdoor dining areas.[147] In response, the president of Health Care for the Homeless in Baltimore County stated that the city already had stringent anti-begging laws and that the proposed legislation would merely make it easier to arrest impoverished citizens, which would in turn create further obstacles to their future self-sufficiency.[147]

In addition to aggressive panhandling, Takoma Park Municipal Code within Montgomery County currently prohibits panhandling in "darkness" (defined as the hours between sunset and sunrise)[148] as well as the solicitation of persons in motor vehicles and in specific locations including bus stops, outdoor cafes and taxi stands.[148]

Massachusetts

editIn 1969, the Pine Street Inn was founded by Paul Sullivan on Pine Street in Boston's Chinatown district and began caring for homeless destitute alcoholics.[149][150] In 1974, Kip Tiernan founded Rosie's Place in Boston, the first drop-in and emergency shelter for women in the United States, in response to the increasing numbers of needy women throughout the country.

In 1980, the Pine Street Inn had to move to larger facilities on Harrison Avenue in Boston[149][150] and in 1984, Saint Francis House had to move its operation from the St. Anthony Shrine on Arch Street to an entire ten-floor building on Boylston Street.[151]

In 1985, the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program was founded to assist the growing numbers of homeless living on the streets and in shelters in Boston and who were suffering from lack of effective medical services.[152][153]

In August 2007, in Boston, Massachusetts, the city took action to keep loiterers, including the homeless, off the Boston Common overnight after a series of violent crimes and drug arrests.[154]

In December 2007, Mayor Thomas M. Menino of Boston announced that the one-night homeless count had revealed that the actual number of homeless living on the streets was down.[155]

In October 2008, Connie Paige of The Boston Globe reported that the number of homeless in Massachusetts had reached an all-time high, primarily due to mortgage foreclosures and the national economic crisis.[156]

In October 2009, as part of the city's Leading the Way initiative, Mayor Thomas Menino of Boston dedicated and opened the Weintraub Day Center, the first city-operated day center for chronically homeless persons. It is a multi-service center providing shelter, counseling, health care, housing assistance, and other support services. It is a 3,400-square-foot (320 m2) facility located in the Woods Mullen Shelter. It is also meant to reduce the strain on the city's hospital emergency rooms by providing services and identifying health problems before they escalate into emergencies. It was funded by $3 million in grants from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD), the Massachusetts Medical Society, and Alliance Charitable Foundation,[157] and the United States Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).[158]

In 2010, there was a continued crackdown on panhandling in downtown Boston, especially the aggressive type. Summonses were being handed out with scheduled court appearances. The results were mixed, and in one upscale neighborhood, Beacon Hill, the resolve of the Beacon Hill Civic Association, which has received only one complaint about panhandlers, was to try to solve the bigger problem, not by criminal actions.[159]

Due to economic constraints in 2010, Governor Deval Patrick had to cut the Commonwealth of Massachusetts 2011 budget so dental care for the majority of adults, including most homeless people, covered by MassHealth (Medicaid) would no longer be provided except for cleaning and extractions, with no fillings, dentures, or restorative care.[160][161] This does not affect dental care for children. The measure took effect in July 2010 and affects an estimated 700,000 adults, including 130,000 seniors.[162]

In September 2010, it was reported that the Housing First Initiative had significantly reduced the chronic homeless single-person population in Boston, Massachusetts, although homeless families were still increasing. Some shelters were reducing the number of beds due to lowered numbers of homeless, and some emergency shelter facilities were closing, especially the emergency Boston Night Center.[163]

There is sometimes corruption and theft by the employees of a shelter, as evidenced by a 2011 investigative report by FOX 25 TV in Boston wherein several Boston public shelter employees were found stealing large amounts of food over some time from the shelter's kitchen for their private use and catering.[164][165]

In October 2017, Boston Mayor Marty Walsh announced the hire of a full-time outreach manager for the Boston Public Library (BPL), whose focus would be to work with staff to provide assessment, crisis intervention, and intensive case management services to homeless individuals who frequent the library. The position is currently based at BPL's Central Library in Copley Square and is funded through the City of Boston's Department of Neighborhood Development and the Boston Public Library, and managed in partnership with Pine Street Inn.[166]

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic caused economic hardship for many residents, resulting in housing precarity and even homelessness for some.[167][168][169]

Michigan

editIn 2014, Michigan had 97,642 homeless individuals on its streets.[170] In the VI-SPADT (Vulnerability Index and Service Prioritization Decision Assistance tool) initiated by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) alongside the Michigan State Housing Development Authority (MSHDA) it was found that 2,462 individuals had 4,564 interactions with the police between June 2014 and April 2015.[170] The 2014 VI-SPADT found that minority populations were overrepresented. 52% of the homeless population were a part of a minority group, as well as people with disabilities of long duration such as chronic health conditions, mental health/cognitive conditions and substance abuse (65%).[170]

The criminalization of panhandling in Michigan has been the subject to much debate in public opinion and in the courts:

In 2011 and 2013, Grand Rapids was the center for this debate. In 2011, the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan (ACLU) filed a federal lawsuit challenging a law that makes begging a crime as a violation of free speech.[171] Prior to this, the ACLU discovered that police officers had been arresting, prosecuting and jailing individual people for requesting financial assistance on the streets. Between 2008 and 2011, there were approximately 400 arrests made by Grand Rapids under an old law that criminalizes the act of begging – 211 of these cases resulted in jail time.[171]

The ACLU focused on the cases of two men. James Speet was arrested for holding a sign reading "Need a Job. God Bless" and Ernest Sims, a veteran, was arrested for asking for spare change for a bus fare.[172] The debate was seated in the fact that other individuals and organizations were allowed to raise funds on the streets without being charged for a crime, yet these man were jailed for the same principle.[171]

The results of these cases were positive for the ACLU side – Judge Robert Jonker ruled in 2012 that the law is unconstitutional and in 2013 the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that begging is protected speech under the First Amendment.[171] On the opposition side of this case and wider debate was the State Attorney General Bill Schuette who appealed the ruling that the state law violated the First Amendment. Schuette contended that the city and the state safety is at risk and there were concerns around pedestrian and vehicle traffic, protection of businesses and tourism, as well as fraud.[173]

The state and argued that it had an interest in preventing Fraud – Schuette contended that not all who beg are legitimately homeless or use the funds they raise to meet basic needs, the money goes to alcohol and other substances. The court agreed with Schuette that preventing fraud and duress are in the interest of the state, but directly prohibiting begging does not align with the prevention of fraud as they are not necessarily intertwined.[173]

This debate resurfaced again in 2016 with the two sides again being prevention of unwanted behaviours and preservation of constitutional rights. In Battle Creek, officials passed a pair of proposals that are aimed at limiting panhandling and loitering throughout the city.[174] City commissioners were split in the vote along with the general public. Under the new ordinances the following situations could lead to legal apprehension by the police – remaining idly within 25 feet of an intersection without a license; soliciting money from anyone near building entrances, restrooms, ATMS or in line; panhandling between sunset and sunrise on public property without an official license or permit; approaching another person in a way that would cause a reasonable person to feel terrorized, intimidated or harassed; forcing oneself upon another i.e. continuing to ask for money after being turned down. Any violations can be considered civil infractions and can result in fines. The bill, aimed at targeting 'aggressive' panhandling was passed in September 2016.[174]

There are a range of implications that come along with the criminalization of begging behaviours. Jessica Vail is the program manager of the Grand Rapids Area Collation to End Homelessness and contends that it is more cost efficient for people to not be homeless and it also keeps our criminal justice system from getting overloaded.[175] Don Mitchell conducted research in 1998 on the criminalization of behaviours associated with homelessness and begging and highlighted the negative effect this has on the cycle of homelessness and crime.[176]

Criminalizing behaviours that are necessary for the survival of homeless people such as begging, sleeping and sitting in public, loitering in parks and on streets and urinating and defecating in public leads them to be subjects of the criminal justice system.[176] ACLU legislative liaison Shelli Weisberg consolidates this notion of a cyclical disadvantage in 2016 – fining people who cannot afford to pay a fine for something they cannot avoid doing and then putting them in a system where they cannot afford to defend themselves or challenge these offences questions how just the criminalization of such acts is.[177]

Minnesota

editIn Minnesota, the prevalence of panhandling, solicitation and begging in relation to homelessness have been deemed to be distinctive to each city. For example, in Stevens County, administrators of social service programs unanimously agreed that rural poverty is distinguishable by location and panhandlers have a low presence in Stevens County, while a high frequency in the city of Minneapolis situated in Hennepin County.[178]

In 2013, a statewide study conducted by the Wilder Foundation on Homelessness indicated the presence of 10,214 homeless in Minnesota. The one-day count was conducted by 1,200 volunteers around 400 locations known to attract homeless such as transitional housing, shelters, drop in sites, hot meal programs and church basements. An increase of six percent in homeless were observed since the last study in 2009, while 55% of the homeless population were females and over 46% were under the age of 21.[179]

In a study conducted by St Stephen's Street Outreach staff, 55 panhandlers were surveyed in downtown Minneapolis to determine why people beg and how local police treat panhandlers. Individual responses neither collectively favoured negative or positive responses for the interaction between police and panhandlers. Examples of responses include that the police 'give you trouble', tell them to 'get the hell out of here' and 'give you a ticket', while other individuals believed that police were 'usually understanding', 'gentle' and 'very friendly and helpful'.[180]

The city council has passed an ordinance that allows those who aggressively solicit or engage in solicitation in prohibited locations to be criminally charged.[181] Minnesota state law does not prohibit passive panhandling, such as holding a sign without verbal interaction and focuses on aggressive panhandling as a breach of the law. Other cities in Minnesota such as Rochester, Brooklyn Center and St Paul have similar versions of the ordinance and have all avoided judicial scrutiny on the grounds of protecting individual privacy against assault based behaviour.[182]

Efforts by the population of Minnesota to redirect the money given to panhandlers to organizations that aim to end homelessness have been implemented in the city of Minneapolis. An example of this is 'Give Real Change', a campaign that began in 2009 with the aim to end homelessness for 300 to 500 people in areas within Minneapolis by the end of 2025. Billboards implemented by the campaign that display 'Say NO To Panhandling and YES To Giving,' urge community members to stop giving money to beggars and alternatively donate it to an organization that allocates money to shelters to end homelessness. The executive director of St Stephens Human Services, Gail Dorfman is a supporter of the initiative and believes that it can act as a long-term solution for homelessness.[183]

In 2020, the City of Minneapolis featured officially and unofficially designated camp sites in city parks for people experiencing homelessness that operated from June 13, 2020, to January 7, 2021. The emergence of encampments on public property in Minneapolis was the result of pervasive homelessness, mitigations measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Minnesota, local unrest after the murder of George Floyd, and an experimental policy of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board that permitted encampments.[184]

At its peak in the summer of 2020, there were thousands of people camping at dozens of park sites across the city. Many of the encampment residents came from outside of Minneapolis to live in the parks.[185] By the end of the permit experiment, four people had died in the city's park encampments,[185] including the city's first homicide victim of 2021, who was stabbed to death inside a tent at Minnehaha Park on January 3, 2021.[186]

Mississippi

editIn 2016, there were at least 1,738 homeless people in Mississippi, according to the 2016 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress prepared by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development.[187] This number is likely to be much greater as this survey only provides a snapshot of homelessness rates at the time of data collection in January 2016. Although homeless people in Mississippi comprise less than 1% of the total US homeless population and there has been a 37% reduction in the number of homeless people in Mississippi from 2010 figures, the state has a comparably high rate of unsheltered homeless people (50%) which is only surpassed by US states such as California, Oregon, Hawaii and Nevada.[187] The state has the second highest rate of unsheltered homeless veterans in the country (60%) and the fourth highest rate of unsheltered homelessness for people with a disability (84%).[187]

Anti-panhandling laws

editHigh rates of homeless people living without suitable accommodation and in public areas creates greater awareness of their presence both by the local community and policing agencies and has resulted in the introduction of laws directed against acts associated with homelessness, otherwise known as vagrancy including begging or panhandling. While in most US states such legislation is primarily enacted and included in city ordinances rather than state law, in Mississippi, the 2015 Mississippi Code provides for a specific definition of vagrancy that allows for "able-bodied persons who go begging for a livelihood" to be punished as vagrants as they are seen to be committing crimes against public peace and security.[188]

Title 99, Chapter 29 of the Code mandates law enforcement officers to arrest known vagrants with those deemed 'vagrant' subjected to fines for a first offence and up to six months imprisonment and the payment of court costs for subsequent offences.[189] These definitions and penalties for homelessness have remained largely unchanged historically in the state of Mississippi which has tended to define vagrants to include those living in idleness or without employment and having no means of support, prostitutes, gamblers as well as beggars.[190]

Those who fall under these population groups continue to be defined as vagrants under the 2015 Mississippi Code.[191] Controversially, such wide and discriminatory definitions have been tied to Mississippi's poor race relations with African Americans with vagrancy legislation in the latter half of the 19th century linked to "keeping black people in their rightful place" on the slave plantations.[192]

As a consequence, Mississippi's 'Black Code' on vagrancy applied in a racially discriminatory manner to African Americans such as ex-slaves and 'idle blacks' as well as white Americans who associated themselves with African Americans.[193] While Mississippi was the first US state to enact such discriminatory and punitive legislation against African Americans, it was certainly not the last, with states including South Carolina, Alabama and Louisiana following Mississippi's lead with similar 'Black Code' legislation in 1865 that targeted homeless ex-slaves.[192]

In Jackson, Mississippi's largest city, begging or panhandling is specifically prohibited under the definition of "commercial solicitation". Begging is banned within 15 feet of public toilets, automatic teller machines (ATMs), parking lots, outdoor eating areas, pay telephones, bus stops, subway stations and entirely within the central business district.[194] Begging is banned after sunset and before sunrise and it is unlawful to "aggressive solicit" by blocking the path of another person, following another person, using abusive language or making a statement or gesture that would cause fear by a reasonable person.[194]

Penalties for a first offence include a warning, citation or seven days community service, subject to law enforcement and prosecutor discretion. For subsequent offences, penalties may include up to 30 days community service, a $1,000 fine or up to 30 days imprisonment.[194] However, passive solicitation is not unlawful. This means that simply holding a sign asking for money is not illegal and in fact, is protected by the Jackson city ordinance that prohibits panhandling. Similar legislation that prohibits begging is also in place in Mississippi's second largest city, Gulfport.[195]

In July 2012, Jackson City Councilman Quentin Whitwell proposed tripling existing fines and implementing longer jail sentences for panhandling in response to heightened community concern about aggressive panhandlers and an escalating panhandling "epidemic".[196] However, this proposal was later rejected by the Jackson City Council amidst concerns from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Mississippi that prohibiting panhandling under city ordinances may violate First Amendment rights under the US Constitution that protect freedom of speech.[197]

On the streets of Jackson, for people experiencing homelessness such as Raymond Quarles, city ordinances such as those originally proposed to prohibit begging increase their susceptibility to counter-productive law enforcement attention and policing activity. For instance, Raymond was arrested at least 10 times in as little as one month in Jackson shortly after experiencing homelessness from the combined effects of relationship breakdown, financial stress and a deterioration in physical health. What Raymond and the ACLU call for are additional support services to assist homeless community members find employment, housing and other support services rather than a "revolving door of crime" and entry into the criminal justice system that is perpetuated through simplistic bans on panhandling and other associated acts of vagrancy.[197]

While the US Supreme Court has not decisively decided on this issue and there is considerable debate as to whether begging constitutes conduct or speech, Fraser (2010) suggests that begging is likely to constitute speech and therefore blanket bans on begging in public areas enacted by local governments as in the case of Mississippi cities such as Jackson and Gulfport are likely to be unconstitutional and in breach of the First Amendment.[198]

Montana

editThis section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2023) |

Nebraska

editIn 2016, over 10,000 people were considered to be living without permanent accommodation in Nebraska, with a little over half of those situated in Omaha and a quarter in the state's capitol of Lincoln.[199] According to The University of Nebraska-Lincoln's Centre on Children, Families and Law a little over half of Nebraska's homeless population is situated in Omaha and a quarter in Lincoln with the balance in spread over the rest of the state.[199] Approximately 10 percent of those homeless in Nebraska are considered 'chronically homeless' and have either been homeless for an entire year or homeless four times in a three-year period.[199] Such statistics have prompted the Nebraskan Government to implement a newly revised 10-year plan for dealing with homelessness which a vision of '[supporting] a statewide Continuum of Care that coordinates services provided to all people and that promotes safe, decent, affordable, and appropriate housing resulting in healthy and viable Nebraskan communities'.[200]

Charles Coley, executive director of the Metro Area Coalition of Care of the Homeless and member of the Nebraska Commission on Housing and Homelessness said that '[the commission] chose to strategically to align [their] goals with the goals of the federal strategic plan to prevent homelessness'.[201] Coley further stated that the 'four goals are end chronic homelessness, secondarily end veteran homelessness, thirdly end child/family and youth homeless and then finally set a path to reducing overall homelessness'. Of those currently living without permanent accommodation in Nebraska, a portion of those are Veterans and those fleeing domestic violence.[201]

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits 'the making of any law respecting an establishment of religion, ensuring that there is no prohibition on the free exercise of religion and abridging the freedom of speech'. In the United States, Panhandling is typically protected by the First Amendment as one has the right to free speech with many states and cities respecting citizen's right to free speech and allowing panhandling.[202] In the Nebraskan city of Omaha, panhandling is currently illegal.[203] Previously, the Omaha Panhandling Ordinance stipulated that 'anyone who wants to solicit money – other than a religious organization or a charity – must obtain written permission from the police chief' with religious organizations and charities protected under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.[203]

As of December 2015, Omaha's current panhandling ordinance states that aggressive panhandling, such as approaching someone several times to ask for money or touching them without consent, is punishable by imprisonment or fine.[204] The new Omaha ordinance also outlaws other particular forms of panhandling including asking for money within 15 feet of an ATM or other location where money is dispensed, following someone to ask them for money, panhandling on private property such as going to someone's front door and asking for money, and panhandling in street traffic.[203][204]

The American Civil Liberties Union has raised numerous concerns over Omaha's previous and current panhandling ordinance as it was a violation of the First Amendment and entered negotiations with the City Attorney's Office about their unconstitutional ordinances.[204] The City Council however did not back down from their stance on panhandling, stating that they originally wanted to implement a blanket ban on the practice as it is a safety hazard and must place the safety of their citizens first.[204]

As a response to Omaha's panhandling ordinance, the Open Door Mission[204] has begun to pass out 'compassion cards' for people to give panhandlers instead of money. The cards resemble a business card which guides the individuals to the Open Door Mission and the services they provide including shelter, food, transportation, clothes and toiletries, and are able to pick people up from the corner of 14th and Douglas Streets.[204]

Nevada

editThis section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023) |

New Jersey

editBegging laws in the state of New Jersey are determined by the ordinances set by each local government. Depending on where an individual is begging the rules and punishments can vary greatly. For example, in Middle Township, it is prohibited to aggressively beg within 100 feet of an ATM, with a first offence punishable by up to a $250 fine, 30 days jail and 5 days community service.[205] Whereas, in New Brunswick, all begging within 25 feet of any bank or ATM is considered aggressive begging, which allows police to issue a cease and desist notice. Failure to comply with the notice may incur a $50 fine for each day of being in violation.[206]

In 2013, the local governments of Middle Township and Atlantic City reached national headlines for passing ordinances that require individuals to register for a free yearly permit before being allowed to beg for money in public.[207][208] Local officials and lawmakers of Middle Township adopted the ordinance in response to complaints from the public in relation to the forceful and persistent tactics used by some panhandlers.[209] However, these begging permits did not last with Middle Township passing amendments that remove the need for permits,[210] and Atlantic City also repealing the permit requirement in April 2016.[211]

The constitutionality of anti-begging laws are contested. Bill Dressel of the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness explains that "it's a complicated area of the law – it's in flux".[212] Recent judicial decisions in the US Supreme Court have challenged local ordinances that prohibit or regulate panhandling in a way that is too vague. Since the decision of Reed v Town of Gilbert the courts have largely struck down panhandling bans on the grounds that they inappropriately limit the content of the speech of individuals that are panhandling.[213] Supporters of anti-begging laws argue that these ordinances do not curtail free speech as they only seek to regulate the manner of begging rather than what is being said.[214]

In 2015, John Fleming, a wheelchair-confined homeless man was arrested in New Brunswick and charged with 'disorderly conduct' for sitting on the sidewalk with a sign that read "BROKE – PLEASE HELP – GOD BLESS YOU – THANK YOU".[215][216] The New Jersey chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU–NJ) successfully challenged the local ordinance on the grounds it violated a person's First Amendment right to free expression.[217] Deputy legal director of ACLU–NJ, Jeanne LoCicero, explained that panhandling, from a constitutional standpoint, is no different from a Girl Scout troop soliciting cookie sales or collecting signatures on a petition.[218] Thus, merely targeting panhandling is problematic as it seeks to prohibit the content of the speech and not the manner of speech. The City of New Brunswick agreed to settle the case by repealing the two ordinances – one that required a permit for begging and another banning unauthorised begging – as there were "legitimate concerns regarding the constitutionality of the Ordinances".[219]

In Paterson, alleged panhandlers arrested by police are given the chance, after being fingerprinted, to engage with social service programs that address their particular needs.[220] Paterson's Police Director, Jerry Speziale, says that the initiative is a "new way to address those in need and enhance the quality of life for all".[221] However, community views on panhandling is vexed, with some Paterson council members calling upon the police to crack down on those whom have dropped out of rehabilitation programs and resumed begging. Paterson Councilman, Alex Mendez, raised that it is an issue of weak enforcement and repeated targeting of panhandlers would eliminate the problem.[222]

An ongoing police crackdown on panhandling was launched in Newark, in July 2016, seeking to deter panhandling in busy areas of the city.[223] Newark Police Director, Anthony Ambrose, said the days of leniency were over, "a panhandler definitely isn't a welcoming sight ... [t]hese operations will continue until the panhandlers get the message". Civil rights activists question the legality of the crackdown, citing the successful case of John Fleming and ACLU-NJ in challenging unconstitutional prohibitions on begging.[224]

New Mexico

editHomelessness is a serious issue throughout the state of New Mexico. Through a demographic examination it becomes evident that New Mexico has a high proportion of ethnographies that are currently and historically socioeconomically disadvantaged.[225] Only Alaska has a higher ratio of Native Americans, and it has a large Hispanic population. Homelessness is a direct cause from an individual not being able to provide themselves with the most basic of necessities to maintain a healthy life hence having a higher proportion of individuals in poverty places a greater risk of an individual becoming homeless.