The history of hip-hop dances encompasses the people and events since the late 1960s that have contributed to the development of early hip-hop dance styles, such as uprock, breaking, locking, roboting, boogaloo, and popping. African Americans created uprock and breaking in New York City. African Americans in California created locking, roboting, boogaloo, and popping—collectively referred to as the funk styles. All of these dance styles are different stylistically. They share common ground in their street origins and in their improvisational nature of hip hop.

More than 50 years old, hip-hop dance became widely known after the first professional street-based dance crews formed in the 1970s in the United States. The most influential groups were Rock Steady Crew, The Lockers, and The Electric Boogaloos who are responsible for the spread of breaking, locking, and popping respectively. The Brooklyn-based dance style uprock influenced breaking early in its development. Boogaloo gained more exposure because it is the namesake of the Electric Boogaloos crew. Uprock, roboting, and boogaloo are respected dance styles but none of them are as mainstream or popular as breaking, locking, and popping.

Parallel with the evolution of hip-hop music, hip-hop social dancing emerged from breaking and the funk styles into different forms. Dances from the 1980s such as the Running Man, the Worm, and the Cabbage Patch entered the mainstream and became fad dances. After the millennium, newer social dances such as the Cha Cha Slide and the Dougie also caught on and became very popular.

Hip-hop dance is not a studio-derived style. Street dancers developed it in urban neighborhoods without a formal process. All of the early substyles and social dances were brought about through a combination of events including inspiration from James Brown, DJ Kool Herc's invention of the break beat, the formation of dance crews, and Don Cornelius' creation of the television show Soul Train.

Beginning of breaking

editAccording to hip-hop activist Afrika Bambaataa[1] and b-boy Richard "Crazy Legs" Colón,[2] the purest hip-hop dance style, breaking (commonly called "breakdancing"), began in the early 1970s as elaborations on how James Brown danced to his song "Get on the Good Foot".[3] People mimicked these moves in their living rooms, in hallways, and at parties. It was at these parties that breaking flourished and developed with the help of a young Clive Campbell. Campbell, better known as DJ Kool Herc, was a Jamaican-born DJ who frequently spun records at neighborhood teenage parties in the Bronx.[4] Jeff Chang, in his book Can't Stop Won't Stop (2005), describes DJ Kool Herc's eureka moment in this way:

- Herc carefully studied the dancers. "I was smoking cigarettes and I was waiting for the records to finish. And I noticed people was waiting for certain parts of the record," he says. It was an insight as profound as Ruddy Redwood's dub discovery. The moment when the dancers really got wild was in a song's short instrumental break, when the band would drop out and the rhythm section would get elemental. Forget melody, chorus, songs—it was all about the groove, building it, keeping it going. Like a string theorist, Herc zeroed in on the fundamental vibrating loop at the heart of the record, the break.[5]

In response to this revelation, Herc developed the Merry-Go-Round technique to extend the breaks—the percussion interludes or instrumental solos within a longer work of music.[6] When he played a break on one turntable, he repeated the same break on the second turntable as soon as the first was finished. He then looped these records one after the other in order to extend the break as long as he wanted: "And once they heard that, that was it, wasn't no turning back," Herc told Chang. "They always wanted to hear breaks after breaks after breaks after breaks." It was during these times that the dancers, later known as break-boys or b-boys, would perform what is known as breaking.[5]

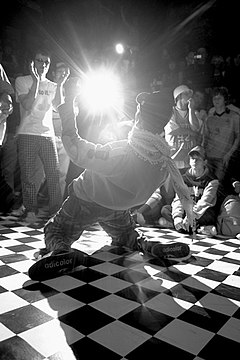

Breaking started out strictly as toprock, footwork-oriented dance moves performed while standing up.[7] Toprock usually serves as the opening to a breaker's performance before transitioning into other dance moves performed on the floor. A separate dance style that influenced toprock is uprock, also called rocking or Brooklyn uprock, because it comes from Brooklyn, New York.[8] The uprock dance style has its roots in gangs.[2][9] Although it looks similar to toprock, uprock is danced with a partner[10] and is more aggressive, involving fancy footwork, shuffles, hitting motions, and movements that mimic fighting.[7] When there was an issue over turf, the two warlords of the feuding gangs would uprock, and whoever won this preliminary dance battle decided where the real fight would be.[1][2] Because uprock's purpose was to moderate gang violence, it never crossed over into mainstream breaking as seen today, except for some specific moves adopted by breakers who use it as a variation for their toprock.[11]

Aside from James Brown and uprock, hip-hop historian Jorge "Popmaster Fabel" Pabon writes that toprock was also influenced by "tap dance, Lindy hop, salsa, Afro-Cuban, and various African and Native American dances."[12] From toprock, breaking progressed to being more floor-oriented, involving freezes, downrock, head spins, and windmills.[13][note 1] These additions occurred due to influences from 1970s martial arts films,[15] influences from gymnastics, and the formation of dance crews[16]—teams of street dancers who get together to develop new moves, create dance routines, and battle other crews. One b-boy move taken from gymnastics is called the flare, which was made famous by gymnast Kurt Thomas and is called the "Thomas flair" in gymnastics.[17]

B-boys Jamie "Jimmy D" White and Santiago "Jo Jo" Torres founded Rock Steady Crew (RSC) in 1977 in the Bronx.[18] Along with Dynamic Rockers and Afrika Bambaataa's Mighty Zulu Kings, they are one of the oldest continually active breaking crews.[note 2] For others to get into the crew, they had to battle one of the Rock Steady b-boys—that was their audition, so to speak.[20] The crew flourished once it came under the leadership of b-boy Richard "Crazy Legs" Colón. Crazy Legs opened a Manhattan chapter of the crew and made his friends and fellow b-boys Wayne "Frosty Freeze" Frost[note 3] and Kenneth "Ken Swift" Gabbert co-vice presidents.[20] RSC was instrumental in the spread of breaking's popularity beyond New York City. They appeared in Wild Style and Beat Street—1980s films about hip-hop culture—as well as in the movie Flashdance.[note 4] They also performed at the Ritz, at the Kennedy Center, and on the Jerry Lewis Telethon.[20] In 1981, the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts hosted a breaking battle between Dynamic Rockers and Rock Steady Crew.[23] The Daily News and National Geographic covered this event.[24] In 1982, their manager Ruza "Kool Lady" Blue organized the New York City Rap Tour, which featured Rock Steady Crew, Afrika Bambaataa, Cold Crush Brothers, the Double Dutch Girls, and Fab 5 Freddy.[25] This tour traveled to England and France, which spread hip-hop culture to those countries.[23][25] In 1983, they performed for Queen Elizabeth II at the Royal Variety Performance.[20] The following year, they recorded a song titled "(Hey You) The Rock Steady Crew", which was commercially released.[26] RSC now has satellite crews based in Japan, the United Kingdom, and Italy.[20]

Capoeira debate

editCapoeira is an Afro-Brazilian martial art, described by Pabon as "a form of self defense disguised as a dance."[27] Its influence on breaking is disputed and debated; one side believes that breaking came from capoeira, while the other side denies this. Capoeira is hundreds of years older than breaking, and uprock is similar in purpose to capoeira in that both translate aggressive combat movements into stylized dance. Both breaking and capoeira are performed to music and, since both art forms are acrobatic, some moves look similar to each other. However, capoeira is more rule-oriented. One rule in capoeira is that a capoeirista's back can never touch the ground.[28][29] In contrast, a breaker's back is almost always on the ground, and the only rule in breaking is that you do not touch your opponent during a battle.[30]

Jelon Vieira and Loremil Machado brought capoeira to the United States in 1975.[31] Throughout this decade Vieira taught capoeira workshops in New York City and started a capoeira performance company called Dance Brazil that toured across the United States.[31] In Gerard Taylor's Capoeira: The Jogo de Angola from Luanda to Cyberspace (2005), master capoeira teacher Mestre Acordeon is quoted as saying: "Demonstrations by Mestre Jelon [Vieira] and Loremil Machado are considered by many to be responsible for the incorporation of capoeira movements into breakdancing."[29] Former Village Voice reporter Sally Banes and her colleague, photographer Martha Cooper, witnessed breaking in 1980 while covering Henry Chalfant's photography exhibit of subway graffiti. She wrote of the dance: "Its spatial level called to mind capoeira, the spectacular Brazilian dance cum martial art form that incorporates kartwheels, kicks, and feints low to the ground, but the two were dissimilar enough in shape and timing that capoeira seemed at most only a distant relative, and certainly one the breakdancers weren't acquainted with—at least on a conscious level."[32] In his book Hip Hop Had a Dream (2008), Damien Morgan states: "Breakdancing can have its origins in capoeira, because it does not focus on injuring the opponent; it rather emphasizes skill towards your opponent, to express yourself away from violence... in most cases, it is blatantly obvious to see some of Breakdancing's foundations in Capoeira."[33]

"We didn't know what the f-ck no capoeira was, man. We were in the ghetto! There were no dance schools, nothing. If there was a dance it was tap and jazz and ballet. I only saw one dance in my life in the ghetto during that time, and it was on Van Nest Avenue in the Bronx and it was a ballet school. Our immediate influence in b-boying was James Brown, point blank."

Rock Steady Crew[2]

Several breaking practitioners and pioneers tend to side with the camp that does not believe breaking came from capoeira. B-boy Crazy Legs states: "We didn't know what the f-ck no capoeira was, man. We were in the ghetto!"[2] According to Pabon, "Unlike the popularity of the martial arts films, capoeira was not seen in the Bronx jams until the 1990s. Top rockin' seems to have developed gradually and unintentionally, leaving space for growth and new additions, until it evolved into a codified form."[27] B-boy crew Spartanic Rockers adds: "Despite of [sic] many rumours and opinions Breaking didn't originate from Capoeira but during the last few years many moves, steps and freezes of this Brazilian (fight-) dance have inspired more and more B-Girls and B-Boys who integrated them into their dance."[34] B-boy Ken Swift was breaking long before he saw capoeira: "In '78 I started [breaking] and I didn't see it [capoeira] til '92 ... I was around, too—I was in Brooklyn, Bronx, Queens, I went around and I didn't see it. What we saw was Kung Fu—we saw Kung Fu from the 42nd Street theaters. So those were our inspirations... when we did the Kung Fu sh-t we switched it up and we put this B-boy flavor into it..."[35]

Funk styles

editWhile breaking was developing in New York City, New York, other styles of dance were developing in California. Unlike breaking, the funk styles—which originated in California—were not originally hip-hop dance styles: they were danced to funk music rather than hip-hop music, and they were not associated with the other cultural pillars of hip-hop (DJing, graffiti writing, and MCing).[36][37][38] The funk styles are actually slightly older than breaking due to fact that boogaloo and locking were developed in the late 1960s.[39][40]

Locking and roboting

editLike breaking, the different moves within the funk styles occurred due to the formation of crews. Don "Campbellock" Campbell created locking, and in 1973 founded The Lockers (originally called The Cambellock Dancers) in Los Angeles.[41][42] Locking is characterized by consistently freezing or "locking" in place while dancing. Campbell developed locking accidentally while pausing in between dance moves when trying to remember how to do the Funky Chicken.[43] He developed routines based on his new style using these pauses or "locks."[44] Chang lists some of the other dance moves performed in locking, including "...points, skeeters, scooby doos, stop 'n go, which-away, and the fancies."[43]

The Lockers made several appearances on Soul Train[45]—the song-and-dance television program featuring funk music, soul music, disco, R&B, and social dancing. They also appeared on The Carol Burnett Show,[46] The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, The Dick Van Dyke Show, and Saturday Night Live.[27] Three original members of The Lockers were Toni Basil, who doubled as the group's manager; Charles "Charles Robot" Washington, a pioneer of roboting; and Fred "Mr. Penguin" Berry, who played the character of Rerun on the television show What's Happening!!.[47] Berry left the group in 1976 to be on the show and was replaced by street dancer Tony "Go-Go" Lewis.[47] After The Lockers disbanded, Tony Go-Go went on to open a locking school in Japan in 1985.[41]

Roboting comes from Richmond, California.[27] Before joining The Lockers, Charles Robot had his own dance crew called The Robot Brothers.[48] He was inspired in 1969 by Robert Shields of Shields and Yarnell, then-a young street artist performing his robotic movements in front of the Hollywood Wax Museum.[49] On October 27, 1973, The Jackson 5 performed "Dancing Machine" on Soul Train, which popularized roboting,[50] but this was not the first time the dance had been performed on the show. Charles Robot had performed roboting on Soul Train two years earlier with his dance partner Angela Johnson.[51]

Boogaloo and popping

editBoogaloo is a freestyle, improvisational street dance movement of soulful steps and robotic movements which make up the foundations of Popping dance and Turfing; Boogaloo can incorporate illusions, restriction of muscles, stops, robot and/or wiggling.[52] Throughout the 1960s and 1970s - Boogaloo groups in Oakland, CA such as One Plus One, the Black Resurgents and the Black Messengers would help popularize the dance.[53] Boogaloo street dance from Oakland would influence Northern California cities and movements would spread to Fresno via the West Coast Relays.[54][55] In Fresno, The Electric Boogaloos are another funk styles crew founded in Fresno in 1977[44] by Sam "Boogaloo Sam" Solomon, Nate "Slide" Johnson, and Joe "Robot Joe" Thomas.[46] Their name was originally The Electric Boogaloo Lockers, but they dropped "Lockers" the following year[44] at the urging of their manager Jeff Kutash[56] after the group moved from Fresno to Long Beach.[57] Boogaloo Sam is credited with innovating popping from earlier boogaloo movements done in Oakland, CA.[37][44][58] However, there is disagreement as to whether he created the dances himself or borrowed moves from other street dancers.[59][60] What is not contested is how influential he and his crew were in exposing popping and boogaloo to mainstream audiences.[59][61]

Boogaloo is both a style of dance and a style of music.[62] It started out as a fad dance, and several songs were released in the 1960s celebrating it including "Boogaloo Down Broadway", "My Baby Likes to Boogaloo", "Hey You! Boo-Ga-Loo", "Do the Boogaloo," "Boogaloo #3," and "Sock Boogaloo."[39][40] In response to this song-and-dance craze, Puerto Rican artists in New York City created a style of music called Bugalú (or Latin boogaloo) that combined mambo, soul, and R&B. Singer Joe Cuba was a pioneer of this style.[40][62]

Although boogaloo was already a fad dance and a music genre in the 1960s, it did not become a dance style until Boogaloo Sam learned it, expanded it, and started performing it in public venues.[63] He was influenced to expand boogaloo by cartoons; the 1960s social dances the Twist, the Popcorn, and the Jerk; and the movements of everyday people.[27][46] As a dance style, it is characterized by rolling hip, knee, and head movements as if the body has no bones.[63] Electric boogaloo is the signature dance style of The Electric Boogaloos.[64] It is a combination of boogaloo and popping.[63]

Popping is based on the technique of quickly contracting and relaxing muscles to cause a jerk in the dancer's body, referred to as a pop or a hit. Popping is also an inadvertent umbrella term that includes several other illusory dance styles such as ticking, liquid, tutting, waving, gliding, twisto-flex, and sliding.[38][44][58] Most of these cannot be traced to a specific person or group and may have influences earlier than hip-hop. Earl "Snake Hips" Tucker was a professional dancer in the 1920s who appeared in the film Symphony in Black and performed at the Cotton Club in Harlem.[65][66] Since hip-hop did not exist in the 1920s his style was considered jazz, but his "slithering, writhing" movement foreshadowed waving and sliding.[67]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Earl "Snake Hips" Tucker |

The most recognizable popping move is the moonwalk. In 1983, Michael Jackson performed the moonwalk—called the backslide in popping context[50]— on ABC's Motown 25 television special.[68] This performance popularized the moonwalk all over the world.[69] However, it was not the first time the backslide had been performed on television or on film. Cab Calloway performed the backslide in 1932,[70][71] and Bill Bailey performed it in the movies Cabin in the Sky (1943) and Rhythm and Blues Revue (1955).[72] Furthermore, in 1982 during a performance in London on Top of the Pops, street dancer Jeffrey Daniel performed the backslide during the song "A Night to Remember".[73][74]

In the 1970s, while Los Angeles was known for locking and Fresno was known for popping, several other cities in Northern California had their own local funk styles. Sacramento was known for a style called sac-ing, San Jose for dime stopping, and Oakland for snake hitting.[27] The San Francisco crew Granny and Robotroid incorporated stepping moves and JROTC rifle drill movements in their dancing to make a unique funk style called Fillmore strutting. This dance was named after the Fillmore district in San Francisco where Granny and Robotroid were from.[75] Granny and Robotroid performed on the Gong Show in 1976.[76] Although strutting had exposure on national television, it (and the rest of the localized funk styles) faded and never became mainstream.

Terminology

editWhen the movies Breakin' and Breakin' 2: Electric Boogaloo were released, all the styles of dance performed in those films were put under the "breakdance" label. In addition, Breakin was released outside the United States as Breakdance: The Movie.[77] The media followed suit by calling all represented styles "breakdancing", which caused a naming confusion among the general public.[27][63][78] This was problematic for two reasons.

The first reason is that "breakdancing" became an inadvertent umbrella term among the general public for both breaking and the funk styles. The funk styles were created in California independent from breaking, which was created in New York.[36][38] They are called funk styles because they were originally danced to funk music. This name gives them a separate identity from breaking, which is traditionally danced to break beats.[63]

The second reason this was problematic is that "breakdancing" was originally called b-boying or breaking by the street dancers who created it.[78][79] A break is a musical interlude during a song—the section on a musical recording where the singing stops and the percussive rhythms are the most aggressive. When 1970s hip-hop DJs played break beats, dancers reacted to those breaks with their most impressive dance moves.[79][80] DJ Kool Herc coined the terms "b-boys" and "b-girls", which stands for "break-boys" and "break-girls."[79] To describe the movement, the suffix "ing" was added after the word identifying the dancer (b-boying) or the music beat (breaking). According to Timothy "Popin Pete" Solomon, one of the original members of the Electric Boogaloos, and Raquel Rivera, author of the book New York Ricans from the Hip Hop Zone (2003), "breakdancing" is a media-coined term and incorrect.[81][82]

Dance crews

editA dance crew is a team of street dancers who come together to develop new moves and battle other crews. As hip-hop culture spread throughout New York City, the more often breaking crews got together to battle against each other. It was during this time that the different dance moves within breaking developed organically.[16][note 5] All styles of hip-hop are rooted in battling,[83] and being a part of a crew was the only way to learn when these styles began because they were not taught in studios: they all started out as social dances.[84]: 74 Forming and participating in a crew is how street dancers practiced, improved, made friends, and built relationships.[85] In breaking in particular, battling is how b-boys/b-girls improved their skill.[86]

Aside from Rock Steady Crew, several breaking crews were active in the 1970s such as Mighty Zulu Kings, Dynamic Rockers, New York City Breakers, SalSoul, Air Force Crew, Crazy Commanders Crew, Starchild La Rock, and Rockwell Association. In the same way b-boy crews were active on the east coast of the United States spreading breaking throughout New York, funk crews were also active on the west coast spreading the funk styles throughout California. Aside from The Lockers and The Electric Boogaloos, other funk styles crews such as Medea Sirkas/Demons of the Mind, Black Messengers, The Robot Brothers, The Go-Go Brothers, Granny and Robotroid, and Chain Reaction were active during the 1970s performing on stage.[87]

Chain Reaction was a four-man dance crew from Reseda, California, whose members included Thomas "T-Bopper" Guzman-Sanchez, Paul "Cool Pockets" Guzman-Sanchez, Robert "Bosco" Winters, and Mike "Deuce" Donley.[88] Just like The Electric Boogaloos had their own signature dance style called electric boogaloo, Chain Reaction also had their own signature dance style called crossover locking.[89] They performed on the talk show Thicke of the Night and in the movie Xanadu.[90] Xanadu premiered in 1980, four years earlier than the hip-hop dance classics Beat Street and Breakin'. Xanadu was the first time boogaloo, popping, and crossover locking were performed on film.[91] In 1984, T-Bopper created a new dance crew called United Street Force. By invitation, this crew performed at the White House for President Ronald Reagan.[92]

Crews still form based on friendships and neighborhoods. For example, dance crew Diversity—formed in 2007[93]—consists of brothers and friends from Essex and London. Crews also form for other reasons such as theme (Jabbawockeez), gender (ReQuest Dance Crew), ethnicity (Kaba Modern), dance style (Massive Monkeys), and age (Hip Op-eration). In 2013, Hip Op-eration performed an exhibition routine at the World Hip Hop Dance Championships in Las Vegas. At the time, their youngest member was 66.[94]

In the 1970s, b-boy crews were neighborhood-based and would engage in battles held at local block parties called "jams".[95] Today crews can battle in organized competitions with other crews from around the world. New Zealand crew ReQuest won the Australian-based competition World Supremacy Battlegrounds in 2009 and the American-based competition Hip Hop International in 2009 and 2010.[96] On October 12, 2010, the Vietnamese Ministry of Culture, Sport, and Tourism presented the Certificate of Merit to dance crew Big Toe for winning a variety of international dance competitions.[97] Dance crews are more prevalent in hip-hop, but hip-hop dance companies do exist. Examples include Zoo Nation (UK), Culture Shock (USA), Lux Aeterna (USA), Boy Blue Entertainment (UK), Unity UK (UK), Bounce Streetdance Company (Sweden), and Funkbrella Dance Company (USA).

Social dancing

editHip-hop social dancing (party dancing) began when hip-hop musical artists started to release songs with an accompanying dance. In 1990, rapper MC Hammer created the Hammer dance[98] and popularized it in his music video "U Can't Touch This". The Hammer dance was a social dance that became wildly popular and then faded as the album it was associated with, Please Hammer, Don't Hurt 'Em, lost popularity. Most social dances are short-lived fad dances, some are line dances, and others spawn new dance styles that stay relevant even after the life of the songs they came from come to an end. The development of hip-hop social dancing extends further back than the 1990s with the Charleston, a jazz dance; Chubby Checker's Twist, which was considered rock & roll; several 1970s fad dances made popular by James Brown; and the influence of the television show Soul Train.

The Charleston was created in the 1920s by African-Americans in Charleston, South Carolina as a rebellion against prohibition.[99] It gained popularity once it was embraced by Caucasians, but it was still considered an immoral dance due to its association with alcohol.[100] This dance relied on partnering and eventually led to the creation of Lindy Hop.[101] Lindy Hop and the Charleston fall under the swing dance genre; however, there is a dance move used in breaking that is taken from the Charleston called the Charlie rock.[11] Singer-songwriter Chubby Checker released the song "The Twist" with an accompanying dance of the same name in 1960. He performed the dance on the television show American Bandstand, and the song reached number one in 1960 and 1962.[102] The Twist was the most popular dance craze of the 1960s because it broke away from the trend of partner dancing enabling people to perform on their own.[103][104][105]

| Hip-Hop Social Dances | |

|---|---|

| Influences | |

The Charleston, the Twist, the Boogaloo, the Good Foot, the Funky Chicken

| |

| 1980s-1990s social dances | |

Two-step, the Wop, the Cabbage Patch, the Roger Rabbit, the Running Man, the Rooftop, the Hammer dance, the Humpty, the Worm, Kriss-Cross, the Bartman, the Butterfly*, the Kid 'n Play kick-step

| |

| 2000s-2010s social dances | |

Toe Wop, Harlem shake, the Chicken Noodle Soup, the Reject**, the Dougie, the Cat Daddy, Getting Lite, Shoulder Lean, Swag Surfin', Bernie Lean, Whip/Nae Nae, Twerking, the Dab

| |

| Line dances | |

Cha Cha slide, Cupid shuffle, the Soulja Boy

| |

| *The Butterfly came from Jamaica.[106] **The Reject is one of many dance moves used in Jerkin'. | |

James Brown was a major contributor to social dance. He popularized several fad dances in the 1970s such as the Mashed Potato,[107] the Boogaloo, and the Good Foot. His accompanying songs to these dances include "(Do the) Mashed Potatoes", "Do the Boogaloo", and "Get on the Good Foot". The song "Do the Boogaloo" influenced Boogaloo Sam when he created the boogaloo dance style,[63] and the Good Foot triggered the creation of breaking.[1] In addition, James Brown also popularized the Funky Chicken, which was a major influence to Don Campbell when he created locking.[43] In an interview with NPR, Lockers' member Adolpho "Shabba Doo" Quiñones stated "We're all children of James Brown... And you know, if James Brown was our father then you'd have to say Don Cornelius was our great uncle."[108]

In 1970, Don Cornelius created Soul Train.[109] Before officially becoming a crew, members of The Lockers made several appearances on this show.[45] They introduced different dance moves such as the Robot, Which-Aways, and the Stop-and-Go during the "Dance of the Week" segment of the broadcast.[108] Disco was very popular during the 1970s, so some dance styles at that time such as waacking and hustle stemmed from disco music rather than funk.[110][111] Hip-hop became more mainstream in the 1980s, and this surge in interest combined with the popularity of Soul Train kick-started the rise of hip-hop social dancing.

One of the more popular social dances created during the 1980s was the Cabbage Patch. The rap group Gucci Crew II created the dance and introduced it in their 1987 song of the same name, "The Cabbage Patch".[112] Another popular social dance was the Roger Rabbit. This dance imitates the floppy movements of the lead cartoon character as seen in the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit.[113] The rap duo Kid 'n Play created the Kid 'n Play kick-step and performed it in their 1990 movie House Party. It is a variation on the Charleston with elements of the Roger Rabbit and the Running Man.[114] The Running Man is one of the most recognizable hip-hop social dances. According to Essence magazine, Paula Abdul created the Running Man and taught the dance to Janet Jackson when she was working as her choreographer during Jackson's Control era.[115][note 6] Jackson further popularized the dance when she performed it in her 1989 music video "Rhythm Nation", and rapper MC Hammer kept the fervor going when he started to do the Running Man in his performances.[115] The pop duo LMFAO brought the Running Man back into the mainstream with their song "Party Rock Anthem", which was named the 2011 song of the summer by Billboard.com.[117] The accompanying dance in the song called The Shuffle combines three social dances: the Running Man, the (half) Charleston, and the T-step.[102]

DJ Troy "Webstar" Ryan and Bianca "Young B" Dupree released the song "Chicken Noodle Soup" in 2006. The dance was so popular, at one point YouTube had over 2,000 video clips of kids performing it.[118] The song sold 335,000 ringtones, but it was not strong enough to sustain momentum for the full length album "Webstar Presents: Caught in the Web", which was not successful.[118] For this reason, the Chicken Noodle Soup song and dance faded. The Dougie comes from Dallas, Texas.[119] The dance was named after the 1980s rapper Doug E. Fresh and popularized in the 2010 song "Teach Me How to Dougie" by the rap group Cali Swag District.[119] According to the Wall Street Journal, the Dougie has been particularly popular as a celebratory dance among professional athletes.[119] In 2010, CNN news anchor Wolf Blitzer performed the Dougie at the Soul Train Music Awards.[120]

Line dances

editThe Cha Cha Slide, the Cupid Shuffle, and the Soulja Boy are examples of urban line dances that were created from hip-hop songs of the same name. These line dances have the same premise as the more widely know Electric Slide. There are variations to the Electric Slide, but the dance is always performed to the song "Electric Boogie" by Marcia Griffiths.[121] In keeping with this tradition, the Cha Cha Slide, the Cupid Shuffle, and the Soulja Boy are always performed to their respective songs.

DJ Willie "Casper" Perry created the song "Cha Cha Slide" in 1996 for a personal trainer in his hometown Chicago.[122] It did not get commercial airplay until 2000 when Chicago radio station WGCI-FM started playing the song as part of its rotation. Soon after, other radio stations across the United States also started playing the song, and this increase in popularity led to a record deal with Universal Music Group.[123] After securing a deal, the label began producing and distributing instructional videos of the dance to nightclubs, which helped spread its popularity.[123] On February 20, 2011, dancers in Anaheim, California set a Guinness world record when 2,387 people performed the dance at the Anaheim Convention Center.[124]

The song "Cupid Shuffle" was released in February 2007 by singer Bryson "Cupid" Bernard from Lafayette, Louisiana. In August 2007, 17,000 people set a world record when they performed the Cupid Shuffle (dance) to his song in Atlanta.[118] The Soulja Boy dance became popular through MySpace when rapper DeAndre "Soulja Boy" Way posted his song "Crank That" to his MySpace page and uploaded an accompanying instructional video showing viewers how to perform the dance. After amassing more than 16 million page views, he was signed to Interscope Records.[118]

Footnotes

edit- ^ Crazy Legs invented the continuous back spin, commonly called the windmill.[14]

- ^ The Mighty Zulu Kings were founded by Afrika Bambaataa in 1973.[19]

- ^ Wayne "Frosty Freeze" Frost died on April 3, 2008. He invented the suicide, a move in which a b-boy does a front flip and lands on their back.[21]

- ^ Richard "Crazy Legs" Colón was one of Jennifer Beals' body doubles in Flashdance.[22]

- ^ B-boy Crazy Legs invented the windmill (continuous back spin) and 1990 (continuous hand spin) b-boy moves by accident.[14]

- ^ Paula Abdul also choreographed the 1987 film The Running Man.[116]

References

editCitations

- ^ a b c "Breakdancing, Present at the Creation". NPR.org. October 14, 2002. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Chang 2005, p. 116.

- ^ Chang 2005, p. 76.

- ^ Roug, Louise (February 24, 2008). "Hip-hop may save Bronx homes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- ^ a b Chang 2005, p. 79.

- ^ "Aug 11, 1973: Hip Hop is born at a birthday party in the Bronx". History.com. August 11, 2011. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Chang 2005, p. 115.

- ^ "Uprocking?!". Spartanic.ch. Archived from the original on July 3, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ^ Chang 2005, p. 138.

- ^ Chang 2006, p. 21. "The structure was different from b-boying/b-girling since dancers in b-boy/b-girl battles took turns dancing, while uprocking was done with partners."

- ^ a b "The Roots". Spartanic.ch. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Chang 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Chang 2005, pp. 117–118, 138.

- ^ a b Cook, Dave. "Crazy Legs Speaks". DaveyD.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

- ^ Chang 2006, p. 20. "Early influences on b-boying and b-girling also included martial arts films from the 1970s."

- ^ a b Chang 2005, p. 136.

- ^ Stoldt, David (October 1980). "Who Really Invented the Flair?" (PDF). International Gymnast Magazine. 22 (10). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Hess 2007, p. xxii. "1977: The Rock Steady Crew is founded by Jojo and Jimmy D in the Bronx, New York."

- ^ "History of the Mighty Zulu Kings". Ness4.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Milosheff, Peter (July 7, 2008). "Rock Steady Crew 32nd Anniversary". The Bronx Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- ^ Irwin, Demetria (April 2008). "Breakdancing pioneer, Frosty Freeze, passes away". New York Amsterdam News. 99 (17): 6. ISSN 0028-7121.

- ^ Del Barco, Mandalit. "Hip Hop Hooray: Breaking into the Big Time". NPR.org. !Mira! magazine. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ a b Kugelberg 2007, p. 59.

- ^ Feuer, Alan (July 7, 2008). "Breaking Out Of the Bronx: A Look Back; A Pioneering Dancer Is the Last of His Breed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2002.

- ^ a b Chang 2005, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 143.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pabon, Jorge. "Physical Graffiti... The History of Hip Hop Dance". DaveyD.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ^ Essien, Aniefre (2008). Capoeira Beyond Brazil: From a Slave Tradition to an International Way of Life. Berkeley: Blue Snake Books. p. 31. ISBN 9781583942550.

Cair no rolê: Roughly translated as "fall into a roll," this means that when you get knocked off your feet, don't fall flat on your back. Capoeiristas are supposed to be adept at this. In the game of capoeira only five parts of the body should touch the ground: your two hands, your two feet, and your head.

- ^ a b Taylor 2007, p. 170.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 135.

- ^ a b Assunção 2005, p. 190.

- ^ Banes, Sally (1994). Writing Dancing: In the Age of Postmodernism. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press. p. 128. ISBN 0819562688.

- ^ Morgan 2008, p. 29.

- ^ "The Roots". Spartanic.ch. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Delgado, Julie (September 26, 2007). "Capoeira and Break-Dancing: At the Roots of Resistance". Capoeira-Connection.com. WireTap Magazine. Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ a b Chang 2006, pp. 18–19. "Although dance forms associate with hip-hop did develop in New York City, half of them (that is, popping and locking) were created on the West Coast as part of a different cultural movement. Much of the media coverage in the 1980s grouped these dance forms together with New York's native dance forms (b-boying/b-girling and uprocking) labeling them all "breakdancing". As a result, the West Coast "funk" culture and movement were overlooked..."

- ^ a b Mackrell, Judith (September 28, 2004). "We have a mission to spread the word". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c Freeman, Santiago (July 1, 2009). "Planet Funk". Dance Spirit. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- ^ a b Nelson 2009, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b c Guzman-Sanchez 2012, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b "The History of Locking". LockerLegends.net. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- ^ Hess 2007, p. xxi. "1973: The Lockers dance group is started in Los Angeles by Don Campbell, the inventor of the locking dance style..."

- ^ a b c Chang 2006, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e Garofoli, Wendy (April 1, 2008). "Urban Legend". Dance Spirit. Archived from the original on May 23, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ a b McMillian, Stephen (June 29, 2011). "Diary of an Ex-Soul Train Dancer: Q&A with Shabba Doo of the Lockers". SoulTrain.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c Chang 2006, p. 23.

- ^ a b Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 44.

- ^ "Old School (O.G.) Hall of Fame". LockerLegends.net. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b McMillan, Stephen (June 18, 2012). "The Soul Train History Book Presents: The Mighty Mighty Jackson 5!". SoulTrain.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

After an Ultra Sheen commercial, The Jackson 5 opened with "Dancing Machine," the last track off Get It Together. This percolating tune, with its relentless throbbing beat anchored by Michael's soulful tenor and the brothers' "ooo-bop-diddy-bop" background vocals, had the Soul Train Gang dancing up a storm. During the song's instrumental break, Michael spun around and did the Robot, a dance that was among the popular fad dances done by the Soul Train Gang since Soul Train's inception... Michael's performance of the robot on the most popular show of the time with black kids, teens and young adults caught on and exposed the dance move to people in various parts of the country who may not have been familiar with the mechanical dance steps Michael so perfectly executed."

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 38.

- ^ The Preservatory Project (2016) Boogaloo Traditions: Interview with Boogaloo Vic & Boogaloo Dana

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez, T. (2012) "1965 and Soul Boogaloo", "The Oakland Funk Boogaloo Generation" Underground Dance Masters: Final History of a Forgotten Era. Praeger.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez, T. (2012) "Oakland Funk Boogaloo to Popping". Underground Dance Masters: Final History of a Forgotten Era. Praeger.

- ^ Higa, B. & Wiggins, C. (1996) "Electric Kingdom" The history of popping and locking, from the people who made it happen. Rap Pages. Sep. 1996: 52-67. Print.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 118.

- ^ "Electric Boogaloos Group History". ElectricBoogaloos.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ a b Chang 2006, p. 23. "Sam [Solomon]'s creation, popping, also became known as the unauthorized umbrella title to various forms within the dance. past and present. Some of these forms include Boogaloo, strut, dime stop, wave, tick, twisto-flex, and slides."

- ^ a b Pagett 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, pp. 110–113, 122.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 122.

- ^ a b Rubin 2007, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e f "'Funk Styles' History And Knowledge". ElectricBoogaloos.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ Morgan 2008, p. 38.

- ^ "Hip-Hop Dance History". DanceHere.com. July 7, 2008. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- ^ "Drop Me Off in Harlem". Kennedy-Center.org. August 29, 2008. Archived from the original on April 19, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ Held, Joy (August 29, 2008). "Earl "Snake Hips" Tucker: The King of Hip-Hop Dance?". Dance. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 121.

- ^ Jackson, Michael (2008). Thriller 25th Anniversary: The Book. ML Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0976889199.

- ^ Paggett 2008, p. 72.

- ^ DiLorenzo, Kris (April 1985). "The Arts. Dance: Michael Jackson did not invent the Moonwalk". The Crisis. 92 (4): 143. ISSN 0011-1422.

Shoot... We did that back in the '30s! Only it was called The Buzz back then.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, pp. 16–17.

- ^ "Remembering Michael Jackson (August 29, 1958 – June 25, 2009)". SoulCulture.com. June 25, 2011. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ "Jeffrey Daniel joins judging panel of Nigerian Idol". AllStreetDance.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, pp. 104–107.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 106.

- ^ "Release dates for Breakin' (1984)". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ a b Scholss 2009, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Israel (director) (2002). The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy (DVD). QD3 Entertainment.

- ^ Kugelberg 2007, p. 140.

- ^ Klopman, Alan (January 1, 2007). "Interview with Popin Pete & Mr. Wiggles at Monsters of Hip Hop – July 7–9, 2006, Orlando, Fl". Dance. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

An important thing to clarify is that the term 'Break dancing' is wrong, I read that in many magazines but that is a media term. The correct term is 'Breakin', people who do it are B-Boys and B-Girls. The term 'Break dancing' has to be thrown out of the dance vocabulary.

- ^ Rivera, Raquel (2003). "It's Just Begun: The 1970s and Early 1980s". New York Ricans from the Hip Hop Zone. New York City: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 72. ISBN 1403960437.

With the barrage of media attention [breaking] received, even terminology started changing. 'Breakdancing' became the catch-all term to describe what originally had been referred to as 'burning', 'going off', 'breaking', 'b-boying', and 'b-girling'. Dance styles that originated in the West Coast such as popping and locking were also grouped under the term 'breakdance. Even though many of hip hop's pioneers accepted the term for a while in the 1980s, they have since reclaimed the original terminology and rejected 'breakdance' as a media-fabricated word that symbolizes the bastardization and co-optation of the art form.

- ^ Schloss 2009, p. 10. "Battling is foundational to all forms of hip-hop and the articulation of its strategy—"battle tactics"—is the backbone of its philosophy of aesthetics."

- ^ Wisner, Heather (2006). "From Street to Studio". Dance. 80 (9): 74–76. ISSN 0011-6009.

- ^ Schloss 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Schloss 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, pp. 80, 104–106.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 57.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, pp. 60–64.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, pp. 73–74, 80.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Phillips, Jayvon (May 30, 2009). "'America's Best Dance Crew' and worldwide Diversity". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 23, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Lapan, Tovin (August 9, 2013). "World's oldest hip-hop dance crew gettin' its swagga on at Las Vegas competition". LasVegasSun.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ^ Schloss 2009, p. 116.

- ^ Tawhiao, Carly (August 20, 2010). "ReQuest on top of the world". Central Leader. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ "Big toe crew bags Asian hip-hop competition prize". The Vietnam News Agency. October 14, 2010.

With a number of prizes won at a variety of international competitions, Big Toe were awarded the Certificate of Merit on Oct. 12 by the Vietnam Electronic Sport and Recreational Sport Association under the Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism.

- ^ Pagett 2008, p. 104.

- ^ Knowles, Mark (2009). The Wicked Waltz and Other Scandalous Dances. Jefferson: MacFarland. pp. 136–139. ISBN 978-0786437085.

- ^ Pagett 2008, p. 168.

- ^ Stearns, Marshall and Jean (1968). Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York City: Macmillan. pp. 322–329.

- ^ a b White, Shelley. "Everyday I'm Shufflin': Top 10 Dance Crazes". AOL.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ^ "Dance". Ebony. 46 (10): 46–48. 1991. ISSN 0012-9011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ Bracaglia, Kate (September 19, 2011). "Sept. 19, 1960: Chubby Checker's "The Twist" hits number 1". AVClub.com. Archived from the original on April 16, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ^ Pagett 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Bury, Martine (2000). "Body Movin'". Vibe. 8 (3): 71. ISSN 1070-4701. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ Pagett 2008, p. 152.

- ^ a b Neil Conan (February 9, 2010). "How 'Soul Train' Got America Dancing". NPR.org (Podcast). Talk of the Nation from NPR News. Archived from the original on February 2, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Stelter, Brian (June 17, 2008). "After 38 Years, 'Soul Train' Gets New Owner". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 28, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ White, Shelley. "Everyday I'm Shufflin': Top 10 Dance Crazes". Music.AOL.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ Guzman-Sanchez 2012, p. 99.

- ^ Pagett 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Pagett 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Pagett 2008, p. 68.

- ^ a b Robertson, Regina (February 2, 2012). "Throwback: The Running Man". Essence. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Hanson, Mary Ellen (1995). Go! Fight! Win! Cheerleading in American Culture. Popular Press. p. 58. ISBN 0879726806.

- ^ Trust, Gary (September 8, 2011). "LMFAO's 'Party Rock Anthem' Named Billboard's 2011 Song of the Summer". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Crosley, Hillary (October 1997). "Song and Dance Routine". Billboard. Vol. 119, no. 43. pp. 14–15. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c Cohen, Ben (November 13, 2010). "What's the Latest Move in Sports? Doing the 'Dougie'". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ Joyella, Mark (November 29, 2010). "Happening Now: Wolf Blitzer Dances The Dougie At Soul Train Awards". Mediaite.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ^ Campbell-Livingston, Cecelia (October 3, 2012). "Truly outstanding". Jamaica Observer. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- ^ Pagett 2008, p. 156.

- ^ a b Hay, Carla (February 2001). "Mr. C The Slide Man Sets Off A Dance Craze On M.O.B.". Billboard. Vol. 113, no. 6. p. 9. ISSN 0006-2510.

The origins of the "Cha-Cha Slide" craze date back to 1996, when Mr. C created the dance for a personal trainer. The song then made its way to R&B station WGCI in Mr. C's hometown of Chicago. The station began playing the song in early 2000, and the tune garnered play in clubs, with label offers soon following. Once it was Universal's project, 'we made some instructional 'Cha-Cha Slide' dance videos and distributed them to clubs,' says senior VP of urban promotion Michael Horton. 'We also promoted the song at various black functions, such as homecoming events at black colleges.'

- ^ Mochan, Amanda (February 25, 2011). "Largest cha-cha slide dance". GuinnessWorldRecords.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

Bibliography

- Assunção, Matthias (2005). Capoeira: The History of an Afro-Brazilian Martial Art. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 0714680869.

- Chang, Jeff (2005). Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 031230143X.

- Chang, Jeff (2006). Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip-Hop. New York City: BasicCivitas. ISBN 0465009093.

- Guzman-Sanchez, Thomas (2012). Underground Dance Masters: Final History of a Forgotten Era. Santa Barbara: Praeger. ISBN 0313386927.

- Hess, Mickey, ed (2007). Icons of hip hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture. Volume I. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313339031.

- Kugelberg, Johan (2007). Born in the Bronx. New York City: Rizzoli International Publications Inc. ISBN 0789315408.

- Morgan, Damien (2008). Hip Hop Had a Dream. Volume I: The Artful Movement. Milton Keynes: AuthorHouse UK Ltd. ISBN 1438902042.

- Nelson, Tom (2009). 1000 Novelty & Fad Dances. Bloomington: AuthorHouse. ISBN 1438926383.

- Pagett, Matt (2008). The Best Dance Moves in the World... Ever. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0811863034.

- Rubin, Rachel; Melnick, Jeffrey (2006). Immigration and American Popular Culture: An Introduction. New York City: New York University Press. ISBN 0814775527.

- Schloss, Joseph (2009). Foundation: B-Boys, B-Girls and Hip-Hop Culture in New York. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195334051.

- Taylor, Gerard (2007). Capoeira: The Jogo de Angola from Luanda to Cyberspace. Volume II. Berkeley: Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1583941835.

External links

edit- "A Dance Teacher's Guide to Hip Hop" article from Dance Teacher magazine