The grey reef shark or gray reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, sometimes misspelled amblyrhynchus or amblyrhinchos)[2] is a species of requiem shark, in the family Carcharhinidae. One of the most common reef sharks in the Indo-Pacific, it is found as far east as Easter Island and as far west as South Africa. This species is most often seen in shallow water near the drop-offs of coral reefs. It has the typical "reef shark" shape, with a broad, round snout and large eyes. It can be distinguished from similar species by the plain or white-tipped first dorsal fin, the dark tips on the other fins, the broad, black rear margin on the tail fin, and the lack of a ridge between the dorsal fins. Most individuals are less than 1.88 m (6.2 ft) long.

| Grey reef shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Carcharhinus |

| Species: | C. amblyrhynchos

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos (Bleeker, 1856)

| |

| |

| Range of the grey reef shark | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Carcharias amblyrhynchos Bleeker, 1856 | |

The grey reef shark is a fast-swimming, agile predator that feeds primarily on free-swimming bony fishes and cephalopods. Its aggressive demeanor enables it to dominate many other shark species on the reef, despite its moderate size. Many grey reef sharks have a home range on a specific area of the reef, to which they continually return. However, they are social rather than territorial. During the day, these sharks often form groups of five to 20 individuals near coral reef drop-offs, splitting up in the evening as the sharks begin to hunt. Adult females also form groups in very shallow water, where the higher water temperature may accelerate their growth or that of their unborn young. Like other members of its family, the grey reef shark is viviparous, meaning the mother nourishes her embryos through a placental connection. Litters of one to six pups are born every other year.

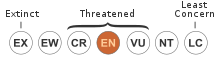

The grey reef shark was the first shark species known to perform a threat display, a stereotypical behavior warning that it is prepared to attack.[3] The display involves a "hunched" posture with characteristically dropped pectoral fins, and an exaggerated, side-to-side swimming motion. Grey reef sharks often do so if they are followed or cornered by divers to indicate they perceive a threat. This species has been responsible for a number of attacks on humans, and should be treated with caution, especially if it begins to display. It has been caught in many fisheries and is susceptible to local population depletion due to its low reproduction rate and limited dispersal. As a result, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed this species as endangered.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

editDutch ichthyologist Pieter Bleeker first described the grey reef shark in 1856 as Carcharias (Prionodon) amblyrhynchos, in the scientific journal Natuurkundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indië. Later authors moved this species to the genus Carcharhinus. The type specimen was a 1.5 metres (4.9 ft)-long female from the Java Sea.[4] Other common names used for this shark around the world include black-vee whaler, bronze whaler, Fowler's whaler shark, graceful shark, graceful whaler shark, grey shark, grey whaler shark, longnose blacktail shark, school shark, and shortnose blacktail shark. Some of these names are also applied to other species.[2]

In older literature, the scientific name of this species was often given as C. menisorrah.[5] The blacktail reef shark (C. wheeleri), native to the western Indian Ocean, is now regarded as the same species as the grey reef shark by most authors. It was originally distinguished from the grey reef shark by a white tip on the first dorsal fin, a shorter snout, and one fewer upper tooth row on each side.[6] Based on morphological characters, vertebral counts, and tooth shapes, Garrick (1982) concluded the grey reef shark is most closely related to the silvertip shark (C. albimarginatus).[7] This interpretation was supported by a 1992 allozyme phylogenetic analysis by Lavery.[8]

Description

editThe grey reef shark has a streamlined, moderately stout body with a long, blunt snout and large, round eyes. The upper and lower jaws each have 13 or 14 teeth (usually 14 in the upper and 13 in the lower). The upper teeth are triangular with slanted cusps, while the bottom teeth have narrower, erect cusps. The tooth serrations are larger in the upper jaw than in the lower. The first dorsal fin is medium-sized, and no ridge runs between the second dorsal fin and it. The pectoral fins are narrow and falcate (sickle-shaped).[4]

The coloration is grey above, sometimes with a bronze sheen, and white below. The entire rear margin of the caudal fin has a distinctive, broad, black band. Dusky to black tips are on the pectoral, pelvic, second dorsal, and anal fins.[9] Individuals from the western Indian Ocean have a narrow, white margin at the tip of the first dorsal fin; this trait is usually absent from Pacific populations.[5] Grey reef sharks that spend time in shallow water eventually darken in color, due to tanning.[10] Most grey reef sharks are less than 1.9 m (6.2 ft) long.[4] The maximum reported length is 2.6 m (8.5 ft) and the maximum reported weight is 33.7 kg (74 lb).[9]

Distribution and habitat

editThe grey reef shark is native to the Indian and Pacific Oceans. In the Indian Ocean, it occurs from South Africa to India, including Madagascar and nearby islands, the Red Sea, and the Maldives. In the Pacific Ocean, it is found from Southern China to northern Australia and New Zealand, including the Gulf of Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia.[4][9] This species has also been reported from numerous Pacific islands, including American Samoa, the Chagos Archipelago, Easter Island, Christmas Island, the Cook Islands, the Marquesas Islands, the Tuamotu Archipelago, Guam, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, New Caledonia, the Marianas Islands, Palau, the Pitcairn Islands, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, the Hawaiian Islands, and Vanuatu.[1]

Generally a coastal, shallow-water species, grey reef sharks are mostly found in depths less than 60 m (200 ft).[11] However, they have been known to dive to 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[2] They are found over continental and insular shelves, preferring the leeward (away from the direction of the current) sides of coral reefs with clear water and rugged topography. They are frequently found near the drop-offs at the outer edges of the reef, particularly near reef channels with strong currents,[12] and less commonly within lagoons. On occasion, this shark may venture several kilometers out into the open ocean.[4][11]

Biology and ecology

editAlong with the blacktip reef shark (C. melanopterus) and the whitetip reef shark (Triaenodon obesus), the grey reef shark is one of the three most common sharks inhabiting Indo-Pacific reefs. They actively expel most other shark species from favored habitats, even species larger in size.[3] In areas where this species co-exists with the blacktip reef shark, the latter species occupies the shallow flats, while the former stays in deeper water.[4] Areas with a high abundance of grey reef sharks tend to contain few sandbar sharks (C. plumbeus), and vice versa; this may be due to their similar diets causing competitive exclusion.[11] The consumptive influence of grey reef sharks on reef fish communities is likely to vary depending on whether sharks forage within the reef environment, or on pelagic resources (like they have been observed to do at Palmyra Atoll).[13]

On the infrequent occasions when they swim in oceanic waters, grey reef sharks often associate with marine mammals or large pelagic fishes, such as sailfish (Istiophorus platypterus). One account has around 25 grey reef sharks following a large pod of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.), along with 25 silky sharks (C. falciformis) and a single silvertip shark.[14] Rainbow runners (Elagatis bipinnulata) have been observed rubbing against grey reef sharks, using the sharks' rough skin to scrape off parasites.[15]

Grey reef sharks are themselves prey for larger sharks, such as the silvertip shark.[9] At Rangiroa Atoll in French Polynesia, great hammerheads (Sphyrna mokarran) feed opportunistically on grey reef sharks that are exhausted from pursuing mates.[16] Known parasites of this species include the nematode Huffmanela lata and several copepod species that attach to the sharks' skin,[17][18] and juvenile stages of the isopods Gnathia trimaculata and G. grandilaris that attach to the gill filaments and septa (the dividers between each gill).[19][20]

Feeding

editGrey reef sharks feed mainly on bony fishes, with cephalopods such as squid and octopus being the second-most important food group, and crustaceans such as crabs and lobsters making up the remainder. The larger sharks take a greater proportion of cephalopods.[21] These sharks hunt individually or in groups, and have been known to pin schools of fish against the outer walls of coral reefs for feeding.[15] Hunting groups of up to 700 grey reef sharks have been observed at Fakarava atoll in French Polynesia.[22][23] They excel at capturing fish swimming in the open, and they complement hunting whitetip reef sharks, which are more adept at capturing fish inside caves and crevices.[4] Their sense of smell is extremely acute, being capable of detecting one part tuna extract in 10 billion parts of sea water.[14] In the presence of a large quantity of food, grey reef sharks may be roused into a feeding frenzy; in one documented frenzy caused by an underwater explosion that killed several snappers, one of the sharks involved was attacked and consumed by the others.[24]

Life history

editDuring mating, the male grey reef shark bites at the female's body or fins to hold onto her for copulation.[14] Like other requiem sharks, it is viviparous; once the developing embryos exhaust their supply of yolk, the yolk sac develops into a placental connection that sustains them to term. Each female has a single functional ovary (on the right side) and two functional uteri. One to four pups (six in Hawaii) are born every other year; the number of young increases with female size. Estimates of the gestation period range from 9 to 14 months. Parturition is thought to take place from July to August in the Southern Hemisphere and from March to July in the Northern Hemisphere. However, females with "full-term embryos" have also been reported in the fall off Enewetak. The newborns measure 45–60 cm (18–24 in) long. Sexual maturation occurs around seven years of age, when the males are 1.3–1.5 m (4.3–4.9 ft) long and females are 1.2–1.4 m (3.9–4.6 ft) long. Females on the Great Barrier Reef mature at 11 years of age, later than at other locations, and at a slightly larger size. The lifespan is at least 25 years.[4][21][25]

Behavior

editGrey reef sharks are active at all times of the day, with activity levels peaking at night.[4] At Rangiroa, groups of around 30 sharks spend the day together in a small part of their collective home range, dispersing at night into shallower water to forage for food. Their home range is about 0.8 km2 (0.31 sq mi).[26] At Enewetak in the Marshall Islands, grey reef sharks from different parts of the reef exhibit different social and ranging behaviors. Sharks on the outer ocean reefs tend to be nomadic, swimming long distances along the reef, while those around lagoon reefs and underwater pinnacles stay within defined daytime and nighttime home ranges.[27] Where strong tidal currents occur, grey reef sharks move against the water, toward the shore with the ebbing tide and back out to sea with the rising tide. This may allow them to better detect the scent of their prey, or afford them the cover of turbid water in which to hunt.[26]

Little evidence of territoriality is seen in the grey reef shark; individuals tolerate others of their species entering and feeding within their home ranges.[28] Off Hawaii, individuals may stay around the same part of the reef up to three years,[29] while at Rangiroa, they regularly shift their locations up to 15 km (9.3 mi).[28] Individual grey reef sharks at Enewetak become highly aggressive at specific locations, suggesting they may exhibit dominant behavior over other sharks in their home areas.[3]

Sociality

editSocial aggregation is well documented in grey reef sharks. In the northwestern Hawaiian Islands, large numbers of pregnant females have been observed slowly swimming in circles in shallow water, occasionally exposing their dorsal fins or backs. These groups last from 11:00 to 15:00, corresponding to peak daylight hours.[29] Similarly, at Sand Island off Johnston Atoll, females form aggregations in shallow water from March to June. The number of sharks per group differs from year to year. Each day, the sharks begin arriving at the aggregation area at 09:00, reaching a peak in numbers during the hottest part of the day in the afternoon, and dispersing by 19:00. Individual sharks return to the aggregation site every one to six days. These female sharks are speculated to be taking advantage of the warmer water to speed their growth or that of their embryos. The shallow waters may also enable them to avoid unwanted attention by males.[10]

Off Enewetak, grey reef sharks exhibit different social behaviors on different parts of the reef. Sharks tend to be solitary on shallower reefs and pinnacles. Near reef drop-offs, loose aggregations of five to 20 sharks form in the morning and grow in number throughout the day before dispersing at night. In level areas, sharks form polarized schools (all swimming in the same direction) of around 30 individuals near the sea bottom, arranging themselves parallel to each other or slowly swimming in circles. Most individuals within polarized schools are females, and the formation of these schools has been theorized to relate to mating or pupping.[26][27]

Threat display

editThe "hunch" threat display of the grey reef shark is the most pronounced and well-known agonistic display (a display directed toward competitors or threats) of any shark. Investigations of this behavior have been focused on the reaction of sharks to approaching divers, some of which have culminated in attacks. The display consists of the shark raising its snout, dropping its pectoral fins, arching its back, and curving its body laterally. While holding this posture, the shark swims with a stiff, exaggerated side-to-side motion, sometimes combined with rolls or figure-8 loops. The intensity of the display increases if the shark is more closely approached or if obstacles are blocking its escape routes, such as landmarks or other sharks. If the diver persists, the shark may either retreat or launch a rapid, open-mouthed attack, slashing with its upper teeth.[3]

Most observed displays by grey reef sharks have been in response to a diver (or submersible) approaching and following it from a few meters behind and above. They also perform the display toward moray eels, and in one instance toward a much larger great hammerhead (which subsequently withdrew). However, they have never been seen performing threat displays toward each other. This suggests the display is primarily a response to potential threats (i.e. predators) rather than competitors. As grey reef sharks are not territorial, they are thought to be defending a critical volume of "personal space" around themselves. Compared to sharks from French Polynesia or Micronesia, grey reef sharks from the Indian Ocean and western Pacific are not as aggressive and less given to displaying.[3]

Human interactions

editGrey reef sharks are often curious about divers when they first enter the water and may approach quite closely, though they lose interest on repeat dives.[4] They can become dangerous in the presence of food, and tend to be more aggressive if encountered in open water rather than on the reef.[14] There have been several known attacks on spearfishers, possibly by mistake, when the shark struck at the speared fish close to the diver. This species will also attack if pursued or cornered, and divers should immediately retreat (slowly and always facing the shark) if it begins to perform a threat display.[4] Photographing the display should not be attempted, as the flash from a camera is known to have incited at least one attack.[3] Although of modest size, they are capable of inflicting significant damage: during one study of the threat display, a grey reef shark attacked the researchers' submersible multiple times, leaving tooth marks in the plastic windows and biting off one of the propellers. The shark consistently launched its attacks from a distance of 6 m (20 ft), which it was able to cover in a third of a second.[15] As of 2008, the International Shark Attack File listed seven unprovoked and six provoked attacks (none of them fatal) attributable to this species.[30]

Although still abundant in pristine sites, grey reef sharks are susceptible to localized depletion due to their slow reproductive rate, specific habitat requirements, and tendency to stay within a certain area. The IUCN has assessed the grey reef shark as endangered; this shark is taken by multispecies fisheries in many parts of its range and used for various products such as shark fin soup and fishmeal.[2] Another threat is the continuing degradation of coral reefs from human development. There is evidence of substantial declines in some populations. Anderson et al. (1998) reported, in the Chagos Archipelago, grey reef shark numbers in 1996 had fallen to 14% of 1970s levels.[31] Robbins et al. (2006) found grey reef shark populations in Great Barrier Reef fishing zones had declined by 97% compared to no-entry zones (boats are not allowed). In addition, no-take zones (boats are allowed but fishing is prohibited) had the same levels of depletion as fishing zones, illustrating the severe effect of poaching. Projections suggested the shark population would fall to 0.1% of pre-exploitation levels within 20 years without additional conservation measures.[32] One possible avenue for conservation is ecotourism, as grey reef sharks are suitable for shark-watching ventures, and profitable diving sites now enjoy protection in many countries, such as the Maldives.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b Simpfendorfer, C.; Fahmi, Bin Ali, A.; , D.; Utzurrum, J.A.T.; Seyha, L.; Maung, A.; Bineesh, K.K.; Yuneni, R.R.; Sianipar, A.; Haque, A.B.; Tanay, D.; Gautama, D.A.; Vo, V.Q. (2020). "Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T39365A173433550. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T39365A173433550.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos". FishBase. April 2009 version.

- ^ a b c d e f Martin, R.A. (March 2007). "A review of shark agonistic displays: comparison of display features and implications for shark-human interactions". Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology. 40 (1): 3–34. doi:10.1080/10236240601154872.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization. pp. 459–461. ISBN 978-92-5-101384-7.

- ^ a b Randall, J.E.; Hoover, J.P. (1995). Coastal fishes of Oman. University of Hawaii Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-8248-1808-1.

- ^ a b Fowler, S.L.; Cavanagh, R.D.; Camhi, M.; Burgess, G.H.; Cailliet, G.M.; Fordham, S.V.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. & Musick, J.A. (2005). Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. pp. 106–109, 284–285. ISBN 978-2-8317-0700-6.

- ^ Garrick, J.A.F. (1982). Sharks of the genus Carcharhinus. NOAA Technical Report, NMFS Circ. 445.

- ^ Lavery, S. (1992). "Electrophoretic analysis of phylogenetic relationships among Australian carcharhinid sharks". Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 43 (1): 97–108. doi:10.1071/MF9920097.

- ^ a b c d Bester, C. Biological Profiles: Grey Reef Shark Archived 2008-06-04 at the Wayback Machine. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on April 29, 2009.

- ^ a b Economakis, A.E.; Lobel, P.S. (1998). "Aggregation behavior of the grey reef shark, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, at Johnston Atoll, Central Pacific Ocean". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 51 (2): 129–139. doi:10.1023/A:1007416813214. S2CID 46066734.

- ^ a b c Papastamatiou, Y.P.; Wetherbee, B.M.; Lowe, C.G. & Crow, G.L. (2006). "Distribution and diet of four species of carcharhinid shark in the Hawaiian Islands: evidence for resource partitioning and competitive exclusion". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 320: 239–251. Bibcode:2006MEPS..320..239P. doi:10.3354/meps320239.

- ^ Dianne J. Bray, 2011, Grey Reef Shark, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, in Fishes of Australia, accessed 25 August 2014, http://www.fishesofaustralia.net.au/Home/species/2881 Archived 2014-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dunn, Ruth E.; Bradley, Darcy; Heithaus, Michael R.; Caselle, Jennifer E.; Papastamatiou, Yannis P. (2022-01-21). "Conservation implications of forage base requirements of a marine predator population at carrying capacity". iScience. 25 (1): 103646. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j3646D. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103646. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 8728395. PMID 35024583. S2CID 245303571.

- ^ a b c d Stafford-Deitsch, J. (1999). Red Sea Sharks. Trident Press. pp. 19–24, 27–32, 74–75. ISBN 978-1-900724-28-9.

- ^ a b c Bright, M. (2000). The Private Life of Sharks: The Truth Behind the Myth. Stackpole Books. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-0-8117-2875-1.

- ^ Whitty, J. (2007). The Fragile Edge: Diving and Other Adventures in the South Pacific. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-618-19716-3.

- ^ Justine, J. (July 2005). "Huffmanela lata n. sp. (Nematoda: Trichosomoididae: Huffmanelinae) from the shark Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos (Elasmobranchii: Carcharhinidae) off New Caledonia". Systematic Parasitology. 61 (3): 181–184. doi:10.1007/s11230-005-3160-8. PMID 16025207. S2CID 915034.

- ^ Newbound, D.R.; Knott, B. (1999). "Parasitic copepods from pelagic sharks in Western Australia". Bulletin of Marine Science. 65 (3): 715–724.

- ^ Coetzee, M.L.; Smit, N.J.; Grutter, A.S. & Davies, A.J. (February 2009). "Gnathia trimaculata n. sp. (Crustacea: Isopoda: Gnathiidae), an ectoparasite found parasitising requiem sharks from off Lizard Island, Great Barrier Reef, Australia". Systematic Parasitology. 72 (2): 97–112. doi:10.1007/s11230-008-9158-2. PMID 19115084. S2CID 8645018.

- ^ Coetzee, M.L.; Smit, N.J.; Grutter, A.S. & Davies, A.J. (2008). "A New Gnathiid (Crustacea: Isopoda) Parasitizing Two Species of Requiem Sharks from Lizard Island, Great Barrier Reef, Australia". Journal of Parasitology. 94 (3): 608–615. doi:10.1645/ge-1391r.1. PMID 18605791.

- ^ a b Wetherbee, B.M.; Crow, C.G. & Lowe, C.G. (1997). "Distribution, reproduction, and diet of the gray reef shark Carcharhinus amblyrhychos in Hawaii". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 151: 181–189. Bibcode:1997MEPS..151..181W. doi:10.3354/meps151181.

- ^ "Gombessa IV expedition". Archived from the original on 2020-06-11. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ^ Gombessa IV on arte.tv (archive.org)

- ^ Halstead, B.W.; Auerbach, Paul S. & Campbell, D.R. (1990). A Color Atlas of Dangerous Marine Animals. CRC Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8493-7139-4.

- ^ Robbins, W.D. (2006). Abundance, demography and population structure of the grey reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) and the white tip reef shark (Triaenodon obesus) (Fam. Charcharhinidae). PhD thesis, James Cook University.

- ^ a b c Martin, R.A. Coral Reefs: Grey Reef Shark. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on April 30, 2009.

- ^ a b McKibben J.N.; Nelson, D.R. (1986). "Pattern of movement and grouping of gray reef sharks, Carcharhinus amblyrhyncos, at Enewetak, Marshall Islands". Bulletin of Marine Science. 38: 89–110.

- ^ a b Nelson, D.R. (1981). "Aggression in sharks: is the grey reef shark different?". Oceanus. 24: 45–56.

- ^ a b Taylor, L.R. (1993). Sharks of Hawaii: Their Biology and Cultural Significance. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 21–24. ISBN 978-0-8248-1562-2.

- ^ ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark. International Shark Attack File, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. Retrieved on May 1, 2009.

- ^ Anderson, R.C.; Sheppard, C.; Spalding, M. & Crosby, R. (1998). "Shortage of sharks at Chagos". Shark News. 10: 1–3.

- ^ Robbins, W.D.; Hisano, M.; Connolly, S.R. & Choat, J.H. (2006). "Ongoing collapse of coral reef shark populations". Current Biology. 16 (23): 2314–2319. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.044. PMID 17141612.

External links

edit- "Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, Grey reef shark" at FishBase

- "Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos (Grey Reef Shark)" at IUCN Red List

- "Biological Profiles: Grey reef shark" at Florida Museum of Natural History Archived 2008-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Coral Reefs: Grey Reef Shark" at ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research

- "Species description of Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos" at Shark-References.com

- Photos of Grey reef shark on Sealife Collection