The West African giraffe (Giraffa peralta[2] or Giraffa camelopardalis peralta), also known as the Niger giraffe,[1] is a species or subspecies of the giraffe distinguished by its light colored spots. Its last self-sustaining herd is in southwest Niger, supported by a series of refuges in Dosso Region and the tourist center at Kouré, some 80km southeast of Niamey.[3][4]

| West African giraffe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Near Kouré, Niger | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Giraffidae |

| Genus: | Giraffa |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | G. c. peralta

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Giraffa camelopardalis peralta Thomas, 1898

| |

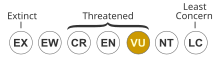

| |

| Range in dark orange | |

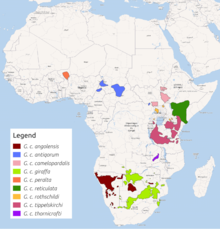

In the 19th century it ranged from Senegal to Lake Chad,[5] yet in 2011 this subspecies only survives in a few isolated pockets containing about 400 individuals in total.[6] All captive so-called "West African giraffe" are now known to be the Kordofan giraffe (G. c. antiquorum).[5]

Evolutionary history

editOlder studies on giraffe subspecies have caused some researchers to question the separate status of G. c. peralta and the Kordofan giraffe (G. c. antiquorum). Genetic testing published in 2007 confirmed the distinctiveness of the West African giraffe.[5][7][8][9]

Most captive giraffes from northwestern Africa are in French zoological parks, a result of the French colonies in West Africa. Those giraffes were formerly treated as G. c. peralta. However, since genetic analysis revealed that only giraffes to the west of Lake Chad belong to this subspecies, the populations in European zoos are in fact Kordofan giraffes (G. c. antiquorum). The West African giraffe is more closely related to the giraffes of East Africa than to those of Central Africa. Its ancestor may have migrated from East to North Africa during the Quaternary and then to West Africa with the development of the Sahara desert. At its largest, Lake Chad may have acted as a barrier between West African and Kordofan giraffes during the Holocene.[5]

Distribution and habitat

editThe Nigerien giraffe population relies upon seasonal migration between the relatively drought-resistant lowlands of the Niger River valley and the drier highlands near Kouré. In this area, Tiger bush habitat allows bands of trees to thrive in climates which might otherwise become more typical desert.

Former range

editBefore World War I, at the time of European colonial administrations, West African giraffe lived in pockets across the Sahel and savanna regions of West Africa. Population growth, involving more intensive farming and hunting, a series of droughts since the late 19th century, and environment destruction (both natural and human made) have all contributed to their dramatic decline. As late as the 1960s, prior to the Sahel drought that lasted into the early 1980s, populations identified as G. c. peralta existed in Senegal, Niger, eastern Mali, northern Benin, northern Nigeria, southwest Chad and northern Cameroon. However, recent genetic research has shown that the populations from northern Cameroon and southern Chad actually are the Kordofan giraffe (G. c. antiquorum).[5] Therefore, the giraffes that remain in Waza National Park (Cameroon) belong to the Kordofan giraffe, while the only remaining viable population of the West African giraffe is in Niger.[5] In Niger, herds have been reported from the Agadez Region and across the west and south of the country. Herds regularly traveled into the Gao Region of Mali as well and throughout the Niger River valley of Niger. Drought struck again in the 1980s and 1990s, and in 1991 there were less than 100 in the nation, with the largest herd in the western Dosso Region numbering less than 50 and scattered individuals along the Niger River valley moving from Benin to Mali and clinging on in the W National Park and nearby reserves.[4]

Ecology and behaviour

editThe West African giraffe survive primarily on a diet of leaves from Acacia albida and Hyphaene thebaica, as well as Annona senegalensis, Parinari macrophylla, Piliostigma reticulatum, and Balanites aegyptiaca.[4] In the late 1990s, an anti-desertification project for the area around Niamey encouraged the development of woodcutting businesses. An unintended effect of this was the destruction of much tiger bush and giraffe habitat within the region. The Nigerian government has since moved to limit woodcutting in the area.[10]

Conservation

editIn the mid-1990s there were only 49 in the whole of West Africa. These giraffes were formally protected by the Niger government and have now risen to 600.[11] Conservation efforts since the 1990s have led to a sizable growth in population, though largely limited to the single Dosso herd. From a low of 50 individuals, in 2007 the herd had grown to some 175 wild individuals,[12] 250 in 2010, and 310 in the Nigerian government's 2011 count.[3] There were about 400 to 450 wild individuals as of 2016.[6][13] Intensive efforts have been made within Niger, especially in the area just north of the Dosso Partial Faunal Reserve. From there, the largest existing herd migrates seasonally to the drier highlands along the Dallol Bosso valley, as far north as Kouré, some 80 km southeast of Niamey. This area, though under little formal regulation, is the centre for Nigerian and international efforts to maintain habitat, smooth relations between the herd and area farmers, and provide opportunities for tourism, organised by the Association to Safeguard Giraffes in Niger.

References

edit- ^ a b Fennessy, J.; Marais, A.; Tutchings, A. (2018). "Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. peralta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T136913A51140803. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T136913A51140803.en.

- ^ Groves, Colin; Grubb, Peter (2011). Ungulate Taxonomy. JHU Press. pp. 68–70. ISBN 9781421400938.

- ^ a b Niger : la population des girafes augmente de 24% en 2011 (officiel) Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Xinhua, 2012-03-01.

- ^ a b c Galadima, Mariama (16 July 2008). "Le Sanctuaire des Girafes". Centre d'Echange d'Informations sur la Biodiversité du Niger.

- ^ a b c d e f Hassanin, Alexandre; Ropiquet, Anne; Gourmand, Anne-Laure; Chardonnet, Bertrand; Rigoulet, Jacques (2007). "Mitochondrial DNA variability in Giraffa camelopardalis: consequences for taxonomy, phylogeography and conservation of giraffes in West and central Africa". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 330 (3): 265–274. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2007.02.008. PMID 17434121.

- ^ a b Fennessy, Julian; Bidon, Tobias; Reuss, Friederike; Kumar, Vikas; Elkan, Paul; Nilsson, Maria A.; Vamberger, Melita; Fritz, Uwe; Janke, Axel (2016). "Multi-locus Analyses Reveal Four Giraffe Species Instead of One". Current Biology. 26 (18): 2543–2549. Bibcode:2016CBio...26.2543F. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.036. PMID 27618261.

- ^ Brown, D. M.; Brenneman, R. A.; Koepfli, K. P.; Pollinger, J. P.; Milá, B; Georgiadis, N. J.; Louis Jr, E. E.; Grether, G. F.; Jacobs, D. K.; Wayne, R. K. (2007). "Extensive population genetic structure in the giraffe". BMC Biology. 5: 57. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-57. PMC 2254591. PMID 18154651.

- ^ "Not one but 'six giraffe species'". BBC News (21 December 2007)

- ^ "Giraffes and Frogs Provide More Evidence of New Species Hidden in Plain Sight". ScienceDaily (21 December 2007)

- ^ Geels, Jolijn (2006). Niger. Bradt UK/Globe Pequot Press US. ISBN 978-1-84162-152-4

- ^ "Northern giraffe: Giraffa camelopardalis". Giraffe Conservation Foundation. 14 March 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Projet d’étude et de conservation des Girafes du Niger, Association pour la Sauvegarde des Girafes du Niger (2007).

- ^ Müller-Jung, Friederike (26 September 2016). "Niger: Giraffes Make an Impressive Comeback in Niger". AllAfrica.com. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

Further reading

edit- I. Ciofolo. "West Africa's Last Giraffes: The Conflict between Development and Conservation," Journal of Tropical Ecology, Vol. 11, No. 4 (November 1995), pp. 577–588

- Yvonnick Le Pendu and Isabelle Ciofolo (1999). Seasonal movements of giraffes in Niger. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 15, pp 341–353

External links

edit- Media related to Nigerian Giraffes at Wikimedia Commons

- Data related to Giraffa camelopardalis peralta at Wikispecies

- West African Giraffe Photos & facts on African Wildlife Foundation's website