The Ganja Khanate (also spelled Ganjeh; Persian: خانات گنجه, romanized: Khānāt-e Ganjeh) was a khanate under Iranian suzerainty, which controlled the town of Ganja and its surroundings, now located in present-day Azerbaijan.

Ganja Khanate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1747–1804 | |||||||||

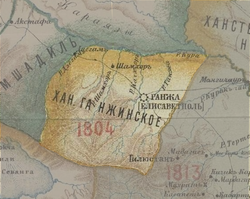

Russian map of the Ganja Khanate, dated 1901 | |||||||||

| Status | Khanate Under Iranian suzerainty | ||||||||

| Capital | Ganja | ||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (administration, judiciary, and literature) Arabic (religious studies) Turkic (locally) Armenian (locally) | ||||||||

| Religion | Shia Islam (majority) Armenian Apostolic Church (large minority) | ||||||||

| Khan | |||||||||

• 1748–1768 | Shahverdi Khan Ziyadoghlu (first) | ||||||||

• 1786–1804 | Javad Khan (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1747 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1804 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

It was governed by members of the Ziyadoghlu clan of the Turkic Qajar tribe, who had previously held the governorship of Karabakh under the Safavid dynasty of Iran. After the death of the Iranian shah (king) Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747), Shahverdi Khan Ziyadoghlu captured Ganja with the aid of the Georgian kings Teimuraz II (r. 1732–1762) and Heraclius II (r. 1744–1798). By paying tribute to either the Karabakh Khanate or Georgia, Shahverdi Khan tried to do everything possible to prevent the khanate from being attacked by his neighbors.

In 1762, he acknowledged the authority of the Zand ruler Karim Khan Zand (r. 1751–1779), who had established his authority in most of Iran. Following Karim Khan's death in 1779, internal chaos resumed. In 1795, Javad Khan submitted to the Qajar ruler Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, whose authority was growing in Iran.

Background

editGanja was a town in the South Caucasus, which had been a part of Iran since the reign of the Safavid king (shah) Ismail I (r. 1501–1524).[1][2] It was part of the province of Karabakh, which was governed by the Ziyadoghlu clan of the Turkic Qajar tribe.[3] Along with Erivan, Karabakh formed the Iranian-ruled part of Armenia, known as Iranian Armenia or Eastern Armenia.[4]

In 1735, after having repelled the Ottoman Empire, the Iranian military commander Nader recognized Ughurlu Khan Ziyadoghlu Qajar as the khan of Karabakh. The latter was later the only khan who did not support Nader when he petitioned to become shah of Iran at the assembly in Mughan. This made Nader Shah split the Karabakh province in order to curtail the power of the Qajars. The Zangezur district was given to the beglerbegi (governor-general) of Tabriz; the autonomy of the Armenian Melikdoms was restored, and Borchalu, Qazzaq and Shamshadil were given to the Georgian king Teimuraz II (r. 1732–1762). Ughurlu Khan was thus only left with Ganja and its surroundings.[5] Nader Shah had Iranian Armenia organized into four khanates; Erivan, Nakhichevan, Ganja, and Karabakh.[6] A khanate was a type of administrative unit governed by a hereditary or appointed ruler subject to Iranian rule. The title of the ruler was either beglarbegi or khan, which was identical to the Ottoman rank of pasha.[7] The khanates were still seen as Iranian dependencies even when the shahs in mainland Iran lacked the power to enforce their rule in the area.[8]

In November 1738, Ughurlu Khan died in a battle against Surkhay Khan of the Gazikumukh Khanate. In 1740, his son Shahverdi Khan Ziyadoghlu succeeded him, but in 1743 he had to seek sanctuary with Teimuraz II in Kartli due to supporting a claimant to the Iranian throne, Sam Mirza. Nader Shah subsequently gave the governorship of Ganja to his tupchi-bashi Hajji Khan.[5]

History

editFollowing Nader Shah's assassination in 1747, Iran fell into turmoil, especially in the South Caucasus. There the Georgians and local khans fought over land.[9]

Shahverdi Khan went back to Ganja, where he overthrew Hajji Khan with the aid of Teimuraz II and Heraclius II (r. 1744–1798). By paying tribute to either the Karabakh Khanate or Georgia, Shahverdi Khan tried to do everything possible to prevent the khanate from being attacked by his neighbors. He also arranged marriages for some of his children in order to form new alliances. His eldest son, Mohammad Hasan Khan, married the sister of Surkhay Khan, while one of his daughters married Ibrahim Khalil Khan of the Karabakh Khanate. After the death of that daughter, one of his other daughters married Ibrahim Khalil Khan. His youngest daughter was given in marriage to Hosein Khan of Shaki, and after the latters death, remarried Mohammad Hasan Agha, the eldest son of Ibrahim Khalil Khan.[10]

By 1762, the Zand ruler Karim Khan Zand (r. 1751–1779) had established his authority across most of Iran,[11] and was eventually acknowledged by Georgia and the various khans of the South Caucasus as their suzerain.[12] He had Shahverdi Khan's brother Reza Qoli taken to the city of Shiraz as a hostage.[13] In 1768, Shahverdi Khan was killed by one of his companions, and was succeeded by Mohammad Hasan Khan, who continued to pay tribute to Georgia and the Karabakh Khanate.[10] In 1778, another son of Shahverdi Khan, Mohammad Khan, became the new khan as a result of the internal issues there and disputes between him and his brothers. His two brothers, Javad Khan and Rahim Khan, fled to Karabakh and the Georgian city Tiflis, respectively.[13] In 1779, Karim Khan died, which led to renewed internal chaos.[12]

Exploiting the instability in Ganja, Heraclius II and Ibrahim Khalil Khan agreed to partition the Ganja khanate in 1780. They took control of Ganja's citadel, blinded Mohammad Khan, and chose Prince Kai-Khosrow Andronikashvili and Hazrat Qoli Beg as their own regents to manage each zone.[13] In 1783, Ibrahim Khalil Khan severed his ties to Georgia, due to the Treaty of Georgievsk that Heraclius II had signed with the Russians,[13] in which he agreed to renounce his loyalty to Iran in return for Russian protection.[14] Ibrahim Khalil Khan was able to organize a widespread rebellion in Ganja that resulted in the ascent to power of a Ziyadoghlu family member with the help of a Daghestani tribe.[13]

With Heraclius II's help, Rahim Khan briefly seized power in Ganja in 1785. However, in 1786, Ibrahim Khalil Khan helped Javad Khan become the new khan of Ganja. In 1787, Heraclius II and the Russian commander Stephan Burnashev intended to attack Ganja. Heraclius II, however, was compelled to make an arrangement with Fath-Ali Khan of Quba in 1789 and return the Shamshadil province to Ganja after Burnashev and his soldiers received orders to participate in the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792.[13] At the same time, the authority of the Qajar ruler Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar was growing in Iran.[15] Like Nader Shah, he saw the South Caucasus, including Georgia, as integral parts of Iran.[16]

Feeling betrayed by Heraclius II's actions and becoming aware of the autonomy enjoyed by the khans, Agha Mohammad Khan invaded the South Caucasus in 1795.[14] Javad Khan acknowledged his suzerainty to finally break free from his dominating neighbours.[13] With most of the region now either under Iranian rule, Agha Mohammad Khan marched to Heraclius II's capital, Tiflis.[17] He was shown the way by Javad Khan.[13] A severe battle followed, which resulted in the victory of Agha Mohammad Khan and Heraclius II's withdrawal. Tiflis was then looted by Agha Mohammad Khan's soldiers for two weeks, resulting in the death of many, as well as the enslavement of women and children.[18] With most of the borders of the Safavid realm reinstated, Agha Mohammad Khan crowned himself shah of Iran and advanced to Khorasan in order to conquer the final province.[19]

The Russian empress Catherine II the Great (r. 1762–1796) viewed the attack on Tiflis as an offense to Russia,[18] and used it as a reason to invade the South Caucasus. In March 1796, she sent a public declaration, written in Persian and Armenian, to all the khans and important figures of the region. The letter explained her reason behind the invasion as a way to protect Georgia and the rest of the South Caucasus from the "usurper" Agha Mohammad Khan.[19] Agha Mohammad Khan's absence convinced the khans (except Erivan and Shirvan) to acknowledge Russian suzerainty, although it only lasted briefly.[20] The Russian expedition was abandoned after the death of Catherine II in November 1796. In the spring of 1797, Agha Mohammad Khan went back to the South Caucasus. Every khan was either driven out, surrendered, or fled. However, he was assassinated in June 1797, which briefly led to renewed turmoil in the area.[18]

Russian conquest

editDuring the first Russo-Persian War (1804-1813), Ganja was considered by Russians, who had earlier supported the Georgian claim to the sovereignty over the khanate, as a town of foremost importance. General Pavel Tsitsianov several times approached Javad khan, asking him to submit to Russian rule, but each time was refused. On November 20, 1803, the Russian army moved from Tiflis, and in December, Tsitsianov started the siege preparations. After heavy artillery bombardment, on January 3, 1804, at 5 a.m., Tsitsianov gave the order to attack the fortress. After fierce fighting, the Russians were able to capture the fortress. Javad Khan was killed, together with his sons. According to a major study of the military events in the Caucasus by John F. Baddeley:

"Thus Gandja, on the pretence that from the time of Tamara it had really belonged to Georgia, though long lost to that country owing to the weakness of her rulers, was invaded, the capital city of the same name stormed after a month's siege (2 January 1804), Djavat Khan killed, and the khanate annexed. "Five hundred Tartars [Azerbaijanis] shut themselves up in a mosque, meaning, perhaps, to surrender, but an Armenian told the soldiers that there were some Daghestanis amongst them, and the name was a death-signal for all, so great is the exasperation of your Majesty's troops against those people for their raids into Georgia and the robber war they carry on", but all the women in the town were spared -- a rare occurrence in Caucasian warfare, and due to Tsitsianoff's strict injunctions."[21]

Ganja was renamed Elisabethpol in honor of Alexander's wife Elisabeth. In 1805 the imperial government officially abolished the khanate, and the military district of Elisabethpol was created. Descendants of the Ziyadoghlu Qajar dynasty bore the name of Ziyadkhanov in the Russian empire.

Administration and population

editIn terms of structure, the Ganja Khanate was a miniature version of Iranian kingship.[22] The administrative and literary language in Ganja until the end of the 19th century was Persian, with Arabic being used only for religious studies, despite the fact that most of the Muslims in the region spoke a Turkic dialect.[23] Persian was also spoken in the judiciary.[24]

The majority of the inhabitants in the Ganja Khanate were Shia Muslims.[25] There was also a large Christian population in the khanate, who were part of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[26] The Armenian community contributed significantly to the khan's income through a range of business endeavors as well as by paying the additional tax levied on non-Muslims.[27] When the Russian army invaded Ganja in 1804, the city had 10,425 residents,[28] which the modern historian Muriel Atkin considers to be "sparse".[27]

Coinage

editEven when the Afsharid dynasty began to decline, minting went on uninterrupted at Ganja. Type A coins bearing the deceased Nader Shah's name were the first to be produced. Type B coins with the phrase "ya, Karim" were first minted by Ganja after Karim Khan took over Iran. These two varieties each weighed one mithqal and were produced in accordance with the Iranian coin standard, being its first local standard. In 1768/69, Ganja started to manufacture lighter 4-shahi abbasi weighing 3.69 g (80% of the second Iranian weight standard), shortly after the number of shahi coins contained in abbasi increased from 4 to 5 across Iran. Up to 1773/74, these coins were in circulation. A new type C coin inscribed with a verse of Karim Khan was introduced as a result of the weight adjustment.[29]

In 1776/77, Iran undertook its next coin reform, which resulted in an increase from five to six shahi in abbasi. Similar to the last time, Ganja reacted to this reform by starting to mint a lighter version weighing 3.07 g (66.67%).[30] The Ganja coins from 1773–1776, however, seem to indicate that there was one more modification to the shahi in abbasi prior to the reform of 1776/77.[31]

The final coins by the Ganja Khanate date back to 1803. Following the Russian conquest, the khanate was instantly abolished, and coin minting stopped.[32]

List of Khans

edit| Khan | Period of Rule | Relationship with Predecessor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Shahverdi Khan | 1747 - 1761 | Member of the Ziyadoghlu branch of the Qajar dynasty. Asserted power. |

| Muhammad Hasan Khan | 1761 - 1781 | Son of Shahverdi Khan. Installed to power with Georgian help. |

| Ibrahim Khalil Khan | 1781 - 1784 | Khan of Karabakh. Took over Ganja Khanate. |

| Hajji Beg | 1784 - 1786 | Relative of Shahverdi Khan and Muhammad Hasan Khan. Rebelled against the Georgians and took back Ganja Khanate. |

| Rahim Khan | 1786 | Son of Shahverdi Khan and brother of Muhammad Hasan Khan. Asserted power after his death. |

| Javad Khan | 1786 - 3 January 1804 | Son of Shahverdi Khan and brother of Muhammad Hasan Khan and Rahim Khan. Enthroned after his brother Rahim was dethroned. |

References

edit- ^ Barthold & Boyle 1965, p. 975.

- ^ Bosworth 2000, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Bournoutian 2021, p. 250.

- ^ Bournoutian 1997, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 2021, p. 251.

- ^ Bournoutian 1997, p. 89.

- ^ Bournoutian 1976, p. 23.

- ^ Bournoutian 2016a, p. xvii.

- ^ Bournoutian 2016b, p. 107.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 2021, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Bournoutian 2021, p. 10.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 2021, p. 234.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bournoutian 2021, p. 252.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 2016b, p. 108.

- ^ Bournoutian 2021, p. 262.

- ^ Bournoutian 2021, p. 17.

- ^ Bournoutian 2016b, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b c Bournoutian 2016b, p. 109.

- ^ a b Bournoutian 2021, p. 18.

- ^ Bournoutian 2021, p. 19.

- ^ John F. Baddeley, The Russian Conquest of the Caucasus, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1908, p. 67, citing "Tsitsianoff's report to the Emperor: Akti, ix (supplement), p. 920".

- ^ Broers 2019, p. 116.

- ^ Bournoutian 1994, p. 1.

- ^ Swietochowski 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Behrooz 2023, p. 16.

- ^ Behrooz 2023, p. 17.

- ^ a b Atkin 1980, p. 83.

- ^ Behrooz 2023, p. 39.

- ^ Akopyan & Petrov 2016, p. 3.

- ^ Akopyan & Petrov 2016, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Akopyan & Petrov 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Akopyan & Petrov 2016, p. 6.

Sources

edit- Akopyan, Alexander; Petrov, Pavel (2016). "The Coinage of Īrawān, Nakhjawān, Ganja and Qarabāḡ Khānates in 1747–1827". State Hermitage: 1–9.

- Atkin, Muriel (1980). Russia and Iran, 1780–1828. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816609246.

- Barthold, W. & Boyle, J.A. (1965). "Gand̲j̲a". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469475.

- Behrooz, Maziar (2023). Iran at War: Interactions with the Modern World and the Struggle with Imperial Russia. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0755637379.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (2000). "Ganja". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume X/3: Fruit–Gāvbāzī. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 282–283. ISBN 978-0-933273-47-4.

- Bournoutian, George (1976). The Khanate of Erevan Under Qajar Rule: 1795–1828. University of California. ISBN 978-0-939214-18-1.

- Bournoutian, George (1994). A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-e Qarabagh. Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56859-011-0.

- Bournoutian, George (1997). "Eastern Armenia from the Seventeenth Century to the Russian Annexation". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. Vol. 1. St. Martin's Press. pp. 81–107. ISBN 0-312-10169-4.

- Bournoutian, George (2016a). The 1820 Russian Survey of the Khanate of Shirvan: A Primary Source on the Demography and Economy of an Iranian Province prior to its Annexation by Russia. Gibb Memorial Trust. ISBN 978-1-909724-80-8.

- Bournoutian, George (2016b). "Prelude to War: The Russian Siege and Storming of the Fortress of Ganjeh, 1803–4". Iranian Studies. 50 (1). Taylor & Francis: 107–124. doi:10.1080/00210862.2016.1159779. S2CID 163302882.

- Bournoutian, George (2021). From the Kur to the Aras: A Military History of Russia's Move into the South Caucasus and the First Russo-Iranian War, 1801–1813. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-44515-4.

- Broers, Laurence (2019). Armenia and Azerbaijan: Anatomy of a Rivalry. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-5052-2.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (2004). Russian Azerbaijan, 1905–1920: The Shaping of a National Identity in a Muslim Community. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52245-8.