The 1900 Galveston hurricane,[1] also known as the Great Galveston hurricane and the Galveston Flood, and known regionally as the Great Storm of 1900 or the 1900 Storm,[2][3] is the deadliest natural disaster in United States history.[4] The strongest storm of the 1900 Atlantic hurricane season, it left between 6,000 and 12,000 fatalities in the United States; the number most cited in official reports is 8,000. Most of these deaths occurred in and near Galveston, Texas, after the storm surge inundated the coastline and the island city with 8 to 12 ft (2.4 to 3.7 m) of water. As of 2024, it remains the fourth deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record, behind Hurricane Fifi of 1974. In addition to the number killed, the storm destroyed about 7,000 buildings of all uses in Galveston, which included 3,636 demolished homes; every dwelling in the city suffered some degree of damage. The hurricane left approximately 10,000 people in the city homeless, out of a total population of fewer than 38,000. The disaster ended the Golden Era of Galveston, as the hurricane alarmed potential investors, who turned to Houston instead. In response to the storm, three engineers designed and oversaw plans to raise the Gulf of Mexico shoreline of Galveston Island by 17 ft (5.2 m) and erect a 10 mi (16 km) seawall.

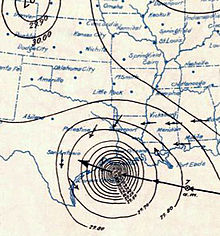

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane on September 8, just before landfall. | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 27, 1900 |

| Extratropical | September 11, 1900 |

| Dissipated | September 15, 1900 |

| Category 4 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 145 mph (230 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 936 mbar (hPa); 27.64 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 6,000–12,000 (Deadliest in U.S. history; fourth-deadliest Atlantic hurricane) |

| Damage | $1.25 billion (2023 USD) |

| Areas affected | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles (Dominican Republic and Cuba landfalls), Turks and Caicos Islands, Bahamas, Gulf Coast of the United States (Texas landfall), Midwestern United States, Mid-Atlantic, New England, Eastern Canada |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1900 Atlantic hurricane season | |

On August 27, 1900, a ship east of the Windward Islands detected a tropical cyclone, the first observed that year. The system proceeded to move steadily west-northwestward and entered the northeastern Caribbean on August 30. It made landfall in the Dominican Republic as a weak tropical storm on September 2. It weakened slightly while crossing Hispaniola, before re-emerging into the Caribbean Sea later that day. On September 3, the cyclone struck modern-day Santiago de Cuba Province and then slowly drifted along the southern coast of Cuba. Upon reaching the Gulf of Mexico on September 6, the storm strengthened into a hurricane. Significant intensification followed and the system peaked as a Category 4 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 145 mph (235 km/h) on September 8. Early on the next day, it made landfall to the south of Houston.[nb 1] The cyclone weakened quickly after moving inland and fell to tropical storm intensity late on September 9. The storm turned east-northeastward and became extratropical over Iowa on September 11. The extratropical system strengthened while accelerating across the Midwestern United States, New England, and Eastern Canada before reaching the Gulf of Saint Lawrence on September 13. After striking Newfoundland later that day, the extratropical storm entered the far North Atlantic Ocean and weakened, with the remnants last observed near Iceland on September 15.

The great storm brought flooding and severe thunderstorms to portions of the Caribbean, especially Cuba and Jamaica. It is likely that much of South Florida experienced tropical storm-force winds, though mostly minor damage occurred. Hurricane-force winds and storm surge inundated portions of southern Louisiana, though the cyclone left no significant structural damage or fatalities in the state. The hurricane brought strong winds and storm surge to a large portion of east Texas, with Galveston suffering the brunt of the impact. Farther north, the storm and its remnants continued to produce heavy rains and gusty winds, which downed telegraph wires, signs, and trees in several states. Fatalities occurred in other states, including fifteen in Ohio, two in Illinois, two in New York, one in Massachusetts, and one in Missouri. Damage from the storm throughout the U.S. exceeded US$34 million.[nb 2] The remnants also brought severe impact to Canada. In Ontario, damage reached about C$1.35 million, with CAD$1 million to crops.[nb 3] The remnants of the hurricane caused at least 52 deaths – and possibly as many as 232 deaths – in Canada, mostly due to sunken vessels near Newfoundland and the French territory of Saint-Pierre. Throughout its path, the storm caused more than $35.4 million in damage. ($1.3 billion in 2023.)[nb 4]

Meteorological history

editTropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The storm is believed to have originated from a tropical wave which moved off the west coast of Africa and then emerged into the Atlantic Ocean.[8] However, this is not completely certain because of the limited observational methods available to contemporary meteorologists, with ship reports being the only reliable tool for observing hurricanes.[9] The first formal sighting of the tropical storm occurred on August 27, about 1,000 mi (1,600 km) east of the Windward Islands, when a ship encountered an area of unsettled weather.[5][8] Over the next couple of days, the system moved west-northwestwards and is thought to have maintained its intensity as a weak tropical storm, before it passed through the Leeward Islands and entered the Caribbean Sea on August 31.[5]

On September 1, Father Reese Gangoite, the director of the Belen College Observatory in Havana, Cuba, noted that the storm was in its formative stages, with only vague indications of a small tropical cyclone to the southwest of Saint Croix.[10] During that day, the system passed to the south of Puerto Rico before it made landfall near Baní, Dominican Republic, early on September 2.[5] Moving west-northwestward, the storm crossed the island of Hispaniola and entered into the Windward Passage near Saint-Marc, Haiti, several hours later.[5] The system made landfall on Cuba near Santiago de Cuba during September 3, before it moved slowly west-northwestward across the island and emerged into Straits of Florida as a tropical storm on September 5.[5] As the system emerged into the Straits of Florida, Gangoite observed a large, persistent halo around the moon, while the sky turned deep red and cirrus clouds moved northwards. This indicated to him that the tropical storm had intensified and that the prevailing winds were moving the system towards the coast of Texas.[11] However, the United States Weather Bureau (as it was then called) disagreed with this forecast, as they expected the system to recurve and make landfall in Florida before impacting the American East Coast.[11][12] An area of high pressure over the Florida Keys ultimately moved the system northwestward into the Gulf of Mexico, where favorable conditions such as warm sea surface temperatures allowed the storm to intensify into a hurricane.[5][11]

In the eastern Gulf of Mexico on September 6, the ship Louisiana encountered the hurricane, and its captain, T. P. Halsey, estimated that the system had wind speeds of 100 mph (160 km/h).[13] The hurricane continued to strengthen significantly while heading west-northwestward across the Gulf. On September 7, the system reached its peak intensity with estimated sustained wind speeds of 145 mph (235 km/h), which made it equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale.[5] That day, the Weather Bureau realized that the storm was continuing west-northwestward across the Gulf of Mexico, rather than turning northward over Florida and the East Coast as it had predicted. However, Weather Bureau director Willis Moore insisted that the cyclone was not of hurricane intensity.[11] The hurricane weakened slightly on September 8 and recurved to the northwest as it approached the coast of Texas, while the Weather Bureau office in Galveston began observing hurricane-force winds by 22:00 UTC.[5][14]

The cyclone made landfall around 8:00 p.m CST on September 8 (02:00 UTC on September 9) to the south of Houston as a Category 4 hurricane.[5] While crossing Galveston Island and West Bay, the eye passed southwest of the city of Galveston.[15] The hurricane quickly weakened after moving inland, falling to tropical storm intensity late on September 9.[5] The storm lost tropical characteristics and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over Iowa by 12:00 UTC on September 11.[5] Moving rapidly east-northeastward, the extratropical system re-intensified, becoming the equivalent of a Category 1 hurricane over Ontario on September 12.[5] The extratropical remnants reached the Gulf of Saint Lawrence early the following day.[5] After crossing Newfoundland and entering the far northern Atlantic hours later, the remnants of the hurricane weakened and were last noted near Iceland on September 15 where the storm finally dissipated.[5]

Background

editThe city of Galveston, formally founded in 1839, had weathered numerous storms, all of which the city survived with ease. In the late 19th century, Galveston was a boomtown with the population increasing from 29,084 people in 1890 to 37,788 people in 1900.[16][17] The city was the fourth largest municipality in terms of population in the state of Texas in 1900, and had among the highest per capita income rates in the U.S.[18] Galveston had many ornate business buildings in a downtown section called The Strand, which was considered the "Wall Street of the Southwest".[19] The city's position on the natural harbor of Galveston Bay along the Gulf of Mexico made it the center of trade in Texas, and one of the busiest ports in the nation.[20] With this prosperity came a sense of complacency,[21] as residents believed any future storms would be no worse than previous events.[nb 5] In fact, Isaac Cline, director of the Weather Bureau's Galveston office, wrote an 1891 article in the Galveston Daily News that it would be impossible for a hurricane of significant strength to strike Galveston Island.[23]

A quarter of a century earlier, the nearby town of Indianola on Matagorda Bay was undergoing its own boom.[24] Then in 1875, a powerful hurricane blew through and nearly destroyed the town. Indianola was rebuilt,[25] though a second hurricane in 1886 caused most of the town's residents to move elsewhere.[26] Many Galveston residents took the destruction of Indianola as an object lesson on the threat posed by hurricanes. Galveston is built on a low, flat island, little more than a large sandbar along the Gulf Coast. These residents proposed a seawall be constructed to protect the city, but the majority of the population and the city's government dismissed their concerns.[27] Cline further argued in his 1891 article in the Daily News that a seawall was not needed due to his belief that a strong hurricane would not strike the island. As a result, the seawall was not built, and development activities on the island actively increased its vulnerability to storms. Sand dunes along the shore were cut down to fill low areas in the city, removing what little barrier there was to the Gulf of Mexico.[27]

Preparations

editOn September 4, the Weather Bureau's Galveston office began receiving warnings from the Bureau's central office in Washington, D.C., that a tropical disturbance had moved northward over Cuba. At the time, they discouraged the use of terms such as "hurricane" or "tornado" to avoid panicking residents in the path of any storm event. The Weather Bureau forecasters had no way of knowing the storm's trajectory, as Weather Bureau director Willis Moore implemented a policy to block telegraph reports from Cuban meteorologists at the Belen Observatory in Havana – considered one of the most advanced meteorological institutions in the world at the time – due to tensions in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War. Moore also changed protocol to force local Weather Bureau offices to seek authorization from the central office before issuing storm warnings.[11]

Weather Bureau forecasters believed that the storm had begun a northward curve into Florida and that it would eventually turn northeastward and emerge over the Atlantic.[11] As a result, the central office of the Weather Bureau issued a storm warning in Florida from Cedar Key to Miami on September 5.[28] By the following day, a hurricane warning was in effect along the coast from Cedar Key to Savannah, Georgia, while storm warnings were displayed from Charleston, South Carolina, to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, as well as from Pensacola, Florida, to New Orleans, Louisiana.[29] Cuban forecasters adamantly disagreed with the Weather Bureau, saying the hurricane would continue west. One Cuban forecaster predicted the hurricane would continue into central Texas near San Antonio.[12]

In Galveston on the morning of September 8, the swells persisted despite only partly cloudy skies. Largely because of the unremarkable weather, few residents saw cause for concern.[30] Few people evacuated across Galveston's bridges to the mainland,[31] and the majority of the population was unconcerned by the rain clouds that began rolling in by midmorning.[30] According to his memoirs, Isaac Cline personally traveled by horse along the beach and other low-lying areas to warn people of the storm's approach.[32] However, these accounts by Cline and his brother, Galveston meteorologist Joseph L. Cline, have since been in dispute.[33][34] Although Isaac Cline is credited with issuing a hurricane warning without permission from the Bureau's central office,[35] author Erik Larson points to his earlier insistence that a seawall was unnecessary and his notion that an intense hurricane could not strike the island, with Cline even considering it "simply an absurd delusion" to believe otherwise.[36] Further, according to Larson, no other survivors are known to have corroborated these accounts.[34]

Impact

editCaribbean

editAntigua reported a severe thunderstorm passing over on August 30, with lower barometric pressures and 2.6 in (66.0 mm) of rain on the island. In Puerto Rico, the storm produced winds up to 43 mph (69 km/h) at San Juan.[10] In Jamaica, heavy rainfall from the storm caused all rivers to swell. Floodwaters severely damaged banana plantations and washed away miles of railroads. Damage estimates ranged in the thousands of British pounds.[37] Heavy rains fell in Cuba in association with the cyclone, including a peak 24-hour total of 12.58 in (319.5 mm) in the city of Santiago de Cuba.[38] The city experienced its worst weather since 1877. The southern end of the city was submerged with about 5 ft (1.5 m) of water. Firefighters and police rescued and aided stranded residents. St. George, a German steamer, ran aground at Daiquirí.[39] A telegraph from the mayor of Trinidad, who was asking for assistance from the U.S. occupation government, indicated that the storm destroyed all crops and left many people destitute.[40]

United States

edit| Deadliest United States hurricanes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Fatalities |

| 1 | 4 "Galveston" | 1900 | 8,000–12,000 |

| 2 | 4 "San Ciriaco" | 1899 | 3,400 |

| 3 | 4 Maria | 2017 | 2,982 |

| 4 | 5 "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 2,823 |

| 5 | 4 "Cheniere Caminada" | 1893 | 2,000 |

| 6 | 3 Katrina | 2005 | 1,392 |

| 7 | 3 "Sea Islands" | 1893 | 1,000–2,000 |

| 8 | 3 "Indianola" | 1875 | 771 |

| 9 | 4 "Florida Keys" | 1919 | 745 |

| 10 | 2 "Georgia" | 1881 | 700 |

| Reference: NOAA, GWU[41][42][nb 6] | |||

The Great Galveston hurricane made landfall on September 8, 1900, near Galveston, Texas. It had estimated winds of 140 mph (225 km/h) at landfall, making the cyclone a Category 4 storm on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale.[5] The hurricane caused great loss of life, with a death toll of between 6,000 and 12,000 people;[31] the number most cited in official reports is 8,000,[26][43] giving the storm the third-highest number of deaths of all Atlantic hurricanes, after the Great Hurricane of 1780 and Hurricane Mitch in 1998.[44] The Galveston hurricane of 1900 is the deadliest natural disaster to strike the United States.[26][43] This loss of life can be attributed to the fact that officials for the Weather Bureau in Galveston brushed off the reports and they did not realize the threat.[45]

More than US$34 million in damage occurred throughout the United States,[14][46] with about US$30 million in Galveston County, Texas, alone.[14] If a similar storm struck in 2010, damage would total approximately US$104.33 billion (2010 USD), based on normalization, a calculation that takes into account changes in inflation, wealth, and population.[43] In comparison, the costliest United States hurricanes – Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017 – both caused about US$125 billion in damage.[47]

The hurricane occurred before the practice of assigning official code names to tropical storms was instituted, and thus it is commonly referred to under a variety of descriptive names. Typical names for the storm include the Galveston hurricane of 1900,[48] the Great Galveston hurricane,[1] and, especially in older documents and publications, the Galveston Flood.[49] It is often referred to by Galveston locals as the Great Storm of 1900 or the 1900 Storm.[2][3]

Florida to Louisiana

editPortions of South Florida experienced tropical storm-force winds, with a sustained wind speed of 48 mph (77 km/h) in Jupiter and 40 mph (64 km/h) in Key West.[10] The hurricane left "considerable damage" in the Palm Beach area, according to The New York Times. Many small boats were torn from their moorings and capsized. The bulkhead of the pier was washed away, while docks and several seawalls were damaged.[50] Rainfall in the state peaked at 5.7 in (140 mm) in Hypoluxo.[51] High winds in North Florida downed telegraph lines between Jacksonville and Pensacola.[52] In Mississippi, the city of Pass Christian recorded winds of 58 mph (93 km/h).[53] Tides produced by the storm inundated about 200 ft (61 m) of railroad tracks in Pascagoula (then known as Scranton), while a quarantine station on Ship Island was swept away.[54]

In Louisiana, the storm produced gale-force winds as far inland as DeRidder and as far east as New Orleans, with hurricane-force winds observed in Cameron Parish. Along the coast, storm surge inundated Johnson Bayou, while tides at some locations reached their highest level since the 1875 Indianola hurricane.[55] Winds and storm surge caused severe damage to rice crops, with at least 25% destroyed throughout the state.[56] The community of Pointe à la Hache experienced a near-total loss of rice crops.[57] Farther east, roads were flooded by storm surge in the communities of Gretna and Harvey near New Orleans, leaving the streets impassable via horses. Winds downed telegraph lines in the southeastern Louisiana in the vicinity of Port Eads.[54] Two men were initially presumed to have drowned after sailing away from Fort St. Philip and not returning in a timely manner,[58] but they were both later found alive.[59]

Texas

editNearly all of the damage in the United States occurred in Texas, with much of the damage in Galveston.[26] However, many communities outside of Galveston also suffered serious damage and it caused many casualties and affected many families economically,[46] with several cities reporting a near or complete loss of all buildings or homes, including Alta Loma, Alvin,[60] Angleton,[61] Brazoria, Brookshire,[60] Chenango,[62] El Campo,[61] Pearland,[60] and Richmond.[61] Throughout Texas – in areas other than Galveston – at least $3 million in damage occurred to cotton crops, $75,000 to telegraph and telephone poles, and $60,000 to railroads.[46]

At Alvin, 8.05 in (204 mm) of rain fell on September 8, the highest 24-hour total for that city in the month of September.[26] The city suffered nine fatalities and about $50,000 in damage.[46] In West Columbia, the storm destroyed the old capitol building of the former Republic of Texas.[26] Eight deaths occurred in the city.[46] In Quintana, the city experienced extensive damage during this storm and a flood in 1899, causing portions of the community to be abandoned.[26] Throughout Brazoria County alone, the hurricane caused nearly $200,000 in damage and 47 deaths.[46] Houston also experienced significant damage. The hurricane wrought damage to many buildings, including a Masonic temple, a railroad powerhouse, an opera house, a courthouse, and many businesses,[63] churches, homes, hotels, and school buildings.[64] Streets were littered with branches from shade trees and downed electrical wires, leaving several roads completely impassable to vehicles.[63] The city of Houston suffered about $250,000 in damage and two deaths,[46] one of which occurred when a man was struck by falling timber.[64]

A train heading for Galveston left Houston on the morning of September 8 at 9:45 a.m. CST (15:45 UTC).[65] It found the tracks washed out, and passengers were forced to transfer to a relief train on parallel tracks to complete their journey. Even then, debris on the track slowed the train's progress to a crawl. The 95 travelers on the train from Beaumont found themselves at the Bolivar Peninsula waiting for the ferry that would carry them to the island. When it arrived, the high seas forced the ferry captain to give up on his attempt to dock. The train crew attempted to return the way they had come, but rising water blocked the train's path.[66] Ten refugees from the Beaumont train sought shelter at the Point Bolivar lighthouse with 190 residents of Port Bolivar who were already there. The 85 who stayed with the train died when the storm surge overran the tops of the cars, while every person inside the lighthouse survived.[67]

Galveston

editFirst news from Galveston just received by train that could get no closer to the bay shore than 6 mi [9.7 km] where the prairie was strewn with debris and dead bodies. About 200 corpses counted from the train. Large steamship stranded 2 mi [3.2 km] inland. Nothing could be seen of Galveston. Loss of life and property undoubtedly most appalling. Weather clear and bright here with gentle southeast wind.

— G.L. Vaughan

Manager, Western Union, Houston,

in a telegram to the Chief of the U.S. Weather Bureau on the day after the hurricane, September 9, 1900[68]

At the time of the 1900 hurricane, the highest point in the city of Galveston was only 8.7 ft (2.7 m) above sea level.[23] The hurricane brought with it a storm surge of over 15 ft (4.6 m) that washed over the entire island. Storm surge and tides began flooding the city by the early morning hours of September 8. Water rose steadily from 3:00 p.m. (21:00 UTC) until approximately 7:30 p.m. (01:30 UTC September 9), when eyewitness accounts indicated that water rose about 4 ft (1.2 m) in just four seconds. An additional 5 ft (1.5 m) of water had flowed into portions of the city by 8:30 p.m. (02:30 UTC September 9).[14] The cyclone dropped 9 in (230 mm) of precipitation in Galveston on September 8, setting a record for the most rainfall for any 24-hour period in the month of September in the city's history.[69]

The highest measured wind speed was 100 mph (160 km/h) just after 6:15 p.m. on September 8 (00:15 UTC September 9), but the Weather Bureau's anemometer was blown off the building shortly after that measurement was recorded.[23] Contemporaneous estimates placed the maximum sustained wind speed at 120 mph (190 km/h). However, survivors reported observing bricks, slate, timbers, and other heavy objects becoming airborne, indicating that winds were likely stronger.[70] Later estimates placed the hurricane at the higher Category 4 classification on the Saffir–Simpson scale.[5] The lowest recorded barometric pressure was 964.4 mbar (28.48 inHg), but this was subsequently adjusted to the storm's official lowest measured central pressure of about 936 mbar (27.6 inHg).[31][5]

Few streets in the city escaped wind damage and all streets suffered water damage,[71] with much of the destruction caused by storm surge. All bridges connecting the island to the mainland were washed away, while approximately 15 mi (24 km) of railroad track was destroyed. Winds and storm surge also downed electrical, telegraph, and telephone wires. The surge swept buildings off their foundations and dismantled them. Many buildings and homes destroyed other structures after being pushed into them by the waves,[72] which even demolished structures built to withstand hurricanes.[70] Every home in Galveston suffered damage, with 3,636 homes destroyed.[14] Approximately 10,000 people in the city were left homeless, out of a total population of nearly 38,000.[73] Portrait and landscape artist Verner Moore White who moved from Galveston the day before the hurricane and survived, had his studio and much of his portfolio destroyed.[74] The Tremont Hotel, where hundreds of people sought refuge during the storm,[75] was severely damaged.[71] All public buildings also suffered damage, including city hall – which was completely deroofed –[72] a hospital, a city gas works, a city water works, and the custom house.[71] The Grand Opera House also sustained extensive damage, but was quickly rebuilt.[76]

Three schools and St. Mary's University were nearly destroyed. Many places of worship in the city also received severe damage or were completely demolished.[71] Of the 39 churches in Galveston, 25 experienced complete destruction, while the others received some degree of damage.[77] During the storm, the St. Mary's Orphans Asylum, owned by the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word, was occupied by 93 children and 10 sisters. As tides began approaching the property, the sisters moved the children into the girl's dorm, as it was newer and sturdier. Realizing they were under threat, the sisters had the children repeatedly sing Queen of the Waves to calm them. As the collapse of the building appeared imminent, the sisters used a clothesline to tie themselves to six to eight children. The building eventually collapsed. Only three of the children and none of the sisters survived.[78] The few buildings that survived, mostly solidly built mansions and houses along the Strand District, are today maintained as tourist attractions.[79]

Early property damage estimates were placed at $25 million.[71] However, itemized estimates from 1901 based on assessments conducted by the Galveston News, the Galveston chamber of commerce, a relief committee, and multiple insurance companies indicated that the storm caused just over $17 million in damage throughout Galveston, including about $8.44 million to residential properties, $500,000 to churches, $656,000 to wharves and shipping properties, $580,000 to manufacturing plants, $397,000 to mercantile buildings, $1.4 million to store merchandise, $670,000 to railroads and telegraph and telephone services, $416,000 to products in shipment, $336,000 to municipality properties, $243,000 to county properties, and $3.16 million to United States government properties. The total also included $115,000 in damage to schools and approximately $100,000 in damage to roads.[77]

The area of destruction – an area in which nothing remained standing after the storm – consisted of approximately 1,900 acres (768.9 ha) of land and was arc-shaped, with complete demolition of structures in the west, south, and eastern portions of the city, while the north-central section of the city suffered the least amount of damage.[71] In the immediate aftermath of the storm, a 3 mi (4.8 km) long, 30 ft (9.1 m) wall of debris was situated in the middle of the island.[72] As severe as the damage to the city's buildings was, the death toll was even greater. Because of the destruction of the bridges to the mainland and the telegraph lines, no word of the city's destruction was able to reach the mainland at first.[80]

On the morning of September 9, one of the few ships at the Galveston wharfs to survive the storm, the Pherabe, set sail and arrived in Texas City on the western side of Galveston Bay with a group of messengers from the city. When they reached the telegraph office in Houston early on September 10, a short message was sent to Texas Governor Joseph D. Sayers and U.S. President William McKinley: "I have been deputized by the mayor and Citizen's Committee of Galveston to inform you that the city of Galveston is in ruins." The messengers reported an estimated five hundred dead; this was initially considered to be an exaggeration.[81] The citizens of Houston knew a powerful storm had blown through and had prepared to provide assistance. Workers set out by rail and ship for the island almost immediately. Rescuers arrived to find the city completely destroyed.[82]

A survey conducted by the Morrison and Fourmy Company in early 1901 indicated a population loss of 8,124, though the company believed that about 2,000 people left the city after the storm and never returned. On this basis, the death toll is no less than 6,000,[83] while estimates range up to 12,000.[31] It is believed 8,000 people—20% of the island's population—had lost their lives.[82] Most had drowned or been crushed as the waves pounded the debris that had been their homes hours earlier.[84] A number of fatalities also occurred after strong winds turned debris into projectiles.[14] Many survived the storm itself but died after several days being trapped under the wreckage of the city, with rescuers unable to reach them. The rescuers could hear the screams of the survivors as they walked on the debris trying to rescue those they could.[84] More people were killed in this single storm than the total of those killed in at least the next two deadliest tropical cyclones that have struck the United States since.[85] The Galveston hurricane of 1900 remains the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history.[26] The disaster did not even spare the buried dead; a number of coffins, including reportedly that of actor-playwright Charles Francis Coghlan who had died in Galveston the previous year, were washed out of the local cemetery to sea by the tidal storm surge.[86]

Midwest

editAfter moving northward from Texas into Oklahoma, the storm produced winds of near 30 mph (48 km/h) at Oklahoma City.[87] The extratropical remnants of the cyclone then re-intensified to the equivalence of a tropical storm and continued to strengthen,[5] bringing strong winds to the Midwestern United States. High winds in Missouri toppled a brick wall under construction in St. Joseph, killing a man and severely injuring another.[88] In Illinois, particularly hard hit was the city of Chicago, which experienced wind gusts up to 84 mph (135 km/h).[10] Thousands of dollars in damage occurred to roofs, trees, signs, and windows. Several people were injured and two deaths occurred in the city, one from a live wire and the other was a drowning after a boat capsized in Lake Michigan.[89] In Wisconsin, many weather stations in the northern and central portions of the state recorded at least 1 in (25 mm) of rainfall, including a peak total of 4.25 in (108 mm) in Shawano.[90] Heavy rains fell in parts of Minnesota. The Minneapolis–Saint Paul area recorded 4.23 in (107 mm) of precipitation over a period of 16 hours. Farther north, several washouts occurred, especially in the northern areas of the state. A bridge, along with a few train cars, were swept away during a washout in Cold Spring.[91]

In Michigan, the storm produced winds around 60 mph (97 km/h) at Muskegon. Tides from Lake Michigan were the highest in several months. According to The Times Herald, the city of Marshall experienced "the severest windstorm of the season", which uprooted trees and damaged several buildings. Throughout the state, winds left at least $12,000 in losses to peach orchards, with many peach trees uprooted. Significant losses to apples and pears also occurred.[92] Rough seas in Lake Erie resulted in several maritime incidents offshore Ohio. The John B. Lyon, a 255 ft (77.7 m) steamer, capsized about 5 mi (8.0 km) north of Conneaut. Fourteen out of sixteen crew members drowned. A survivor suggested that the ship being overloaded may have been a factor in its sinking. About 10 mi (16 km) farther north, the schooner Dundee sank, causing at least one death. In another incident nearby, the steamer City of Erie, with about 300 passengers aboard, was hit by a wave that swept over the bulwarks. The engine slowed and the steamers later reached safety in Canada with no loss of lives.[93] In Toledo, strong winds disrupted telegraph services. Winds also blew water out of parts of the Maumee River and Maumee Bay to such an extent that they were impassable by vessels due to low water levels. A number of vessels were buried in mud several feet deep, while about 20 others were beached.[94]

New York

editOf the many cities in New York affected by the remnants of the hurricane, Buffalo was among the hardest hit. There, winds peaked at 78 mph (126 km/h), downing hundreds of electrical, telegraph, and telephone wires,[95] while numerous trees toppled and some branches fell onto roadways. An oil derrick blew away and landed on the roof of a house, crushing the roof and nearly killing the occupants.[96] A newly built iron works building was virtually destroyed, causing a loss of about $10,000.[97] At the Pan-American Exposition, the storm damaged several structures, including part of the government building, while two towers were destroyed. Losses at the exposition alone were conservatively estimated at $75,000.[98] One death occurred in Buffalo after a woman inadvertently touched a downed electrical wire obscured by debris.[95] Several nearby resorts received extensive damage. At Woodlawn Beach, several dozens of small boats and a pier were destroyed. Nearly all vessels owned by the Buffalo Canoe Club suffered severe damage or destruction at Crystal Beach. A toboggan slide and a restaurant were also destroyed. Losses in Crystal Beach reached about $5,000. Heavy crop losses occurred over western New York, with fallen apples and peaches completely covering the ground at thousands of acres of orchards. Losses reportedly ranged in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.[99]

The rapidly moving storm was still exhibiting winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) while passing well north of New York City on September 12.[100] The New York Times reported that pedestrian-walking became difficult and attributed one death to the storm. A sign pole, snapped by the wind, landed on a 23-year-old man, crushing his skull and killing him instantly, while two others were knocked unconscious. Awnings and signs on many buildings broke and the canvas roofing at the Fire Department headquarters was blown off.[101] Closer to the waterfront, along the Battery seawall, waves and tides were reported to be some of the highest in recent memory of the fishermen and sailors. Spray and debris were thrown over the wall, making walking along the waterfront dangerous. Small craft in New York Harbor were thrown off course and tides and currents in the Hudson River made navigation difficult.[102] In Brooklyn, The New York Times reported that trees were uprooted, signs and similar structures were blown down, and yachts were torn from moorings with some suffering severe damage.[103] Because of the direction of the wind, Coney Island escaped the fury of the storm, though a bathing pavilion at Bath Beach suffered damage from wind and waves.[101]

New England

editIn Connecticut, winds gusted up to about 40 mph (64 km/h). The apple crops, already endangered by drought conditions, suffered severe damage, with The Boston Globe noting that there was, "hardly an apple left on a tree in the entire state".[104] In the town of Orange, twelve large tents at a fair were ripped. At another fair in New Milford, fifteen tents collapsed, forcing closure of the fair.[105] Along the coast, the storm produced abnormally high tides, with tides reaching their highest heights in six years at Westbrook. Water reached the bulkheads and remained there for several hours.[106] In Rhode Island, the storm left damage in the vicinity of Providence. Telegraph and telephone services were interrupted, but not to such a large extent. Some small crafts in Narragansett Bay received damage, while apple orchards experienced slight losses.[107]

Lightning produced by the storm ignited several brush fires in Massachusetts, particularly in the southeastern portions of the state, with winds spreading the flames. In Plymouth and other nearby towns, some residents evacuated from the fires by boat. Most cottages around the Big Long, Gallows,[108] Halfway,[109] and Little Long ponds were reduced to burning coals.[108] In Everett, orchards in the Woodlawn section suffered complete losses of fruit. Two wooden frame building were demolished, while winds also toppled fences throughout the city.[110] Winds damaged many telephone and electric wires in Cambridge. A lineman sent to fix the electrical wires nearly died when a pole snapped during a fierce wind gust. Orchards in the city suffered near complete loss and many shade trees were also damaged. At least a few chimneys toppled and several others were left leaning. A bathhouse at Harvard University lost a portion of its tin roof and its copper cornices.[111] At Cape Cod, a wind speed of 45 mph (72 km/h) was observed at Highland Light in North Truro. Waves breached the sand dunes at multiple locations along the cape, with water sweeping across a county road at Beach Point in North Truro. A number of fishing boats sank and several fish houses received severe damage.[112] One man drowned in a lake near Andover while canoeing during the storm.[113]

Strong winds in Vermont generated rough seas in Lake Champlain. Early reports indicated that a schooner sunk near Adams Ferry with no survivors,[114] but the vessel was later found safely anchored at Westport, New York.[115] According to a man near the lake, all water from the New York portion of the lake was blown to the Vermont side, crashing ashore in waves as high as 15 to 20 ft (4.6 to 6.1 m).[114] In the state capital of Montpelier, several large trees at the state house were uprooted. Within Montpelier and vicinity, farmers suffered some losses to apples and corn. Telephone and telegraph services were almost completely cut off. In Vergennes, a number of telephone wires snapped, while many apples, pears, and plums were blown off the trees. Additional damage to fruit and shade trees occurred in Middlebury and Winooski.[115] The city of Burlington experienced its worst storm in many years. Winds downed all telephone and telegraph wires, whereas many trees had severe damage. Some homes were deroofed.[116]

In New Hampshire, the storm left wind damage in the city of Nashua. Winds tore roofs off a number of buildings, with several roofs landing on the streets or telephone wires. Chimneys in each section of the city collapsed; many people narrowly escaped injury or death. In Nashua and the nearby cities of Brookline and Hollis, thousands of dollars in losses occurred to apple crops, described as "practically ruined".[117] The city of Manchester was affected by "one of the most furious windstorms which visited this city in years". Telephone and telegraph communications were nearly completely out for several hours, while windows shattered and trees snapped. Street railway traffic experienced delays.[118] In Maine, the storm downed trees and chimney and caused property damage in the vicinity of Biddeford.[119]

Canada

edit| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Newfoundland (1)" | 1775 | 4,000–4,163† |

| 2 | "Nova Scotia (1)" | 1873 | 600† |

| 3 | "Nova Scotia (3)" | 1927 | 173–192† |

| 4 | "Labrador" | 1882 | 140 |

| 5 | Hazel | 1954 | 81 |

| 6 | "Newfoundland (2)" | 1883 | 80 |

| 7 | "Nova Scotia (2)" | 1926 | 55–58† |

| 8 | "Galveston" | 1900 | 52–232† |

| 9 | "Newfoundland (3)" | 1935 | 50† |

| 10 | "Saxby Gale" | 1869 | 37+ |

| † – Estimated total | |||

| Source: NOAA[120] | |||

From September 12–September 14, the extratropical remnants of the Galveston hurricane affected six Canadian provinces, resulting in severe damage and extensive loss of life. In Ontario, storm surge in Lake Ontario ranged from 8 to 10 ft (2.4 to 3.0 m), wreaking havoc on vessels, beaching several boats, destroying a number of boats, and setting some others adrift. Many other vessels canceled or postponed their departures. Winds reached as high as 77 mph (124 km/h) in Toronto, breaking windows throughout the city. A fire broke out at a flour mill in Paris, and the flames were fanned by the storm, resulting in $350,000 in damage to the mill and 50 other stores and offices. High winds downed electrical, telegraph, and telephone lines in many areas. Total crop damage in Ontario alone amounted to $1 million. Impact to crops was particularly severe at St. Catharines, where many apple, peach, pear, and plum orchards were extensively damaged, with a loss of thousands of dollars. One person died in Niagara Falls, when a man attempted to remove debris from a pump station, but he was swept away into the river instead. Maximum rainfall in Canada reached 3.9 in (100 mm) in Percé, Quebec.[121]

In Nova Scotia, damage was reported in the Halifax area. A plethora of fences and trees fell over, while windows shattered and a house under construction collapsed. Two schooners were driven ashore at Sydney and a brigantine was also beached at Cape Breton Island. Another schooner, known as Greta, capsized offshore Cape Breton Island near Low Point, with the fate of the crew being unknown. On Prince Edward Island, a few barns, a windmill, and a lobster factory were destroyed. Falling trees downed about 40 electrical wires. A house suffered damage after its own chimney fell and collapsed through the roof. Strong winds also tossed a boxcar from its track. A bridge and wharf at St. Peters Bay were damaged. Fruit crops were almost entirely ruined throughout Prince Edward Island. The majority of loss of life in Canada occurred due to numerous shipwrecks off the coasts of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island. The overall death toll in Canadian waters is estimated to be between 52 and 232, making this at least the eighth deadliest hurricane to affect Canada. The large discrepancy between the fatality figures is due to the fact that many people were reported missing. Thus, the exact number of deaths is unknown.[121]

Aftermath

edit| Costliest U.S. Atlantic hurricanes, 1900–2017 Direct economic losses, normalized to societal conditions in 2018[122] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Cost |

| 1 | 4 "Miami" | 1926 | $235.9 billion |

| 2 | 4 "Galveston" | 1900 | $138.6 billion |

| 3 | 3 Katrina | 2005 | $116.9 billion |

| 4 | 4 "Galveston" | 1915 | $109.8 billion |

| 5 | 5 Andrew | 1992 | $106.0 billion |

| 6 | ET Sandy | 2012 | $73.5 billion |

| 7 | 3 "Cuba–Florida" | 1944 | $73.5 billion |

| 8 | 4 Harvey | 2017 | $62.2 billion |

| 9 | 3 "New England" | 1938 | $57.8 billion |

| 10 | 4 "Okeechobee" | 1928 | $54.4 billion |

| Main article: List of costliest Atlantic hurricanes | |||

The city of Galveston was effectively obliterated.[123] With the city in ruins and railroads to the mainland destroyed, the survivors had little to live on until relief arrived. On September 9, Galveston city officials established the Central Relief Committee for Galveston Storm Sufferers (CRC), chaired by Mayor Walter C. Jones. The CRC was composed of subcommittees for specific aspects of relief efforts, including burial of the deceased, correspondence, distribution of food and water, finances, hospitalization and rehabilitation for the injured, and public safety.[72]

The dead bodies were so numerous that burying all of them was impossible. Initially, bodies were collected by "dead gangs" and then given to 50 African American men – who were forcibly recruited at gunpoint – to load them onto a barge. About 700 bodies were taken out to sea to be dumped. However, after gulf currents washed many of the bodies back onto the beach, a new solution was needed. Funeral pyres were set up on the beaches, or wherever dead bodies were found, and burned day and night for several weeks after the storm. The authorities passed out free whiskey to sustain the distraught men conscripted for the gruesome work of collecting and burning the dead.[124]

With thousands dead and roughly 2,000 survivors leaving the city and never returning according to a Morrison and Fourmy Company survey, Galveston initially experienced a significant population decline.[83] Between 1907 and 1914, Congregation B'nai Israel rabbi Henry Cohen and philanthropist Jacob Schiff spearheaded the Galveston Movement. Cohen, Schiff, and others created the movement to draw Jewish immigrants away from the crowded area along the East Coast and toward cities farther west, such as Galveston. Although approximately 10,000 Jewish immigrants arrived in Galveston during this period, few settled in the city or the island, but about one-fourth of them remained in Texas.[125] The 1910 Census reported a population of 36,891 people in Galveston. Although a decline from the 1900 Census, the population loss of thousands of people was nearly reversed.[126]

In the months prior to the hurricane, valet Charles F. Jones and lawyer Albert T. Patrick began conspiring to murder wealthy businessman William Marsh Rice in order to obtain his wealth. Patrick fabricated Rice's legal will with the assistance of Jones. Rice's properties in Galveston suffered extensive damage during the storm. After being informed of the damage, Rice decided to spend $250,000, the entire balance of his checking account, on repairing his properties. With the duo realizing that they would fail to obtain Rice's wealth, Patrick convinced Jones to kill Rice with chloroform as he slept. Immediately after murdering Rice, Jones forged a large check to Patrick in Rice's name. However, Jones misspelled Patrick's name on the check, arousing suspicion and eventually resulting in their arrests and convictions. Rice's estate was used to open an institute for higher learning in Houston in 1912, which was named Rice University in his honor.[127]

Rebuilding

editSurvivors set up temporary shelters in surplus United States Army tents along the shore. They were so numerous that observers began referring to Galveston as the "White City on the Beach".[128] In the first two weeks following the storm, approximately 17,000 people resided in these tents, vacant storerooms, or public buildings.[129] Others constructed so-called "storm lumber" homes, using salvageable material from the debris to build shelter.[128] The building committee, with a budget of $450,000, opened applications for money to rebuild and repair homes. Accepted applicants were given enough money to build a cottage with three 12 by 12 ft (3.7 by 3.7 m) rooms. By March 1901, 1,073 cottages were built and 1,109 homes had been repaired.[129]

Winifred Bonfils, a young journalist working for William Randolph Hearst, was the first reporter on the line at the hurricane's ground zero in Galveston. She delivered an exclusive set of reports and Hearst sent relief supplies by train.[130] By September 12, Galveston received its first post-storm mail. The next day, basic water service was restored, and Western Union began providing minimal telegraph service.[131] Within three weeks of the storm, cotton was again being shipped out of the port.[132]

A number of cities, businesses, organizations, and individuals made monetary donations toward rebuilding Galveston. By September 15, less than one week after the storm struck Galveston, contributions totaled about $1.5 million. More than $134,000 in donations poured in from New York City alone. Five other major cities – St. Louis, Chicago, Boston, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia – had also donated at least $15,000 by September 15.[133] By state, the largest donations included $228,000 from New York, $67,000 from Texas, $56,000 from Illinois, $53,000 from Massachusetts, and $52,000 from Missouri. Contributions also came from abroad, such as from Canada, Mexico, France, Germany, England, and South Africa,[70] including $10,000 each from Liverpool and Paris. Andrew Carnegie made the largest personal contribution, $10,000, while an additional $10,000 was donated by his steel company.[133]

It was one of those monstrosities of nature which defied exaggeration and fiendishly laughed at all tame attempts of words to picture the scene it had prepared. The churches, the great business houses, the elegant residences of the cultured and opulent, the modest little homes of laborers of a city of nearly forty thousand people; the center of foreign shipping and railroad traffic lay in splinters and debris piled twenty feet above the surface, and the crushed bodies, dead and dying, of nearly ten thousand of its citizens lay under them.

Clara Barton, the founder and president of the American Red Cross and famous for her responses to crises in the latter half of the 19th century, responded to the disaster and visited Galveston with a team of eight Red Cross workers. This would be the last disaster that Barton responded to, as she was 78 years old at the time and would retire in 1904. After Barton and the team observed the catastrophe, the Red Cross set up a temporary headquarters at a four-story warehouse in the commercial district. Her presence in Galveston and appeals for contributions resulted in a substantial amount of donations. Overall, 258 barrels, 1,552 pillow cases, and 13 casks of bedding, clothing, crockery, disinfectants, groceries, hardware, medical supplies, and shoes were received at the warehouse, while $17,341 in cash was donated to the Red Cross. Contributions, both monetary gifts and supplies, were estimated to have reached about $120,000.[72]

Before the hurricane of 1900, Galveston was considered to be a beautiful and prestigious city and was known as the "Ellis Island of the West" and the "Wall Street of the Southwest".[19][134] However, after the storm, development shifted north to Houston, which reaped the benefits of the oil boom, particularly after the discovery of oil at Spindletop on January 10, 1901.[135] The dredging of the Houston Ship Channel began by 1909,[136] which opened in 1914, ending Galveston's hopes of regaining its former status as a major commercial center.[137]

The Galveston city government was reorganized into a commission government in 1901, a newly devised structure wherein the government is made of a small group of commissioners, each responsible for one aspect of governance. This was prompted by fears that the existing city council would be unable to handle the problem of rebuilding the city. The apparent success of the new form of government inspired about 500 cities across the United States to adopt a commission government by 1920. However, the commission government fell out of favor after World War I, with Galveston itself switching to council–manager government in 1960.[138]

Protection

editTo prevent future storms from causing destruction like that of the 1900 hurricane, many improvements to the island were made. The city of Galveston hired a team of three engineers to design structures for protection from future storms – Alfred Noble, Henry Martyn Robert, and H. C. Ripley.[139] The three engineers recommended and designed a seawall. In November 1902, residents of Galveston overwhelmingly approved a bond referendum to fund building a seawall, passing the measure by a vote of 3,085–21.[124] The first 3 mi (4.8 km) of the Galveston Seawall, 17 ft (5.2 m) high, were built beginning in 1902 under the direction of Robert.[140][141] In July 1904, the first segment was completed, though construction of the seawall continued for several decades, with the final segment finished in 1963.[140] Upon completion, the seawall in its entirety stretched for more than 10 mi (16 km).[142]

Another dramatic effort to protect Galveston was its raising, also recommended by Noble, Robert, and Ripley, and similar to the earlier raising of Chicago and Sacramento, California. Approximately 15,000,000 cu yd (11,000,000 m3) of sand was dredged from the Galveston shipping channel to raise the city, some sections by as much as 17 ft (5.2 m).[139] Over 2,100 buildings were raised in the process of pumping sand underneath,[32] including the 3,000-st (2,700-t) St. Patrick's Church.[70] According to historian David G. McComb, the grade of about 500 blocks had been raised by 1911.[139] The seawall was listed among the National Register of Historic Places on August 18, 1977,[142] while the seawall and raising of the island were jointly named a National Historical Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers on October 11, 2001.[143]

In 1915, a storm similar in strength and track to the 1900 hurricane struck Galveston. The 1915 storm brought storm surge up to 12 ft (3.7 m), testing the integrity of the new seawall. Although 53 people on Galveston Island lost their lives in the 1915 storm, this was a great reduction from the thousands who died in 1900.[144] Other powerful tropical cyclones would test the effectiveness of the seawall, including Hurricane Carla in 1961, Hurricane Alicia in 1983, and Hurricane Ike in 2008. Carla primarily caused severe coastal flood-related damage to structures unprotected by the seawall.[26] Following Hurricane Alicia, the Corps of Engineers estimated that the seawall prevented about $100 million in damage.[126] Despite the seawall, Ike left extensive destruction in Galveston due to storm surge, with preliminary estimates indicating that up to $2 billion in damage occurred to beaches, dwellings, hospitals, infrastructure, and ports.[145] Damage in Galveston and surrounding areas prompted proposals for improvements to the seawall, including the addition of floodgates and more seawalls.[146]

Open Era and beyond

editIn historiography, the hurricane and the rebuilding afterward divide what is known as the Golden Era (1875–1900) from the Open Era (1920–1957) of Galveston. The most important long-term impact of the hurricane was to confirm fears that Galveston was a dangerous place to make major investments in shipping and manufacturing operations; the economy of the Golden Era was no longer possible as investors fled.[147] However, the city experienced a significant economic rebound beginning in the 1920s, when Prohibition and lax law enforcement opened up new opportunities for criminal enterprises related to gambling and bootlegging in the city. Galveston rapidly became a prime resort destination enabled by the open vice businesses on the island. This new entertainment-based economy brought decades-long prosperity to the island.[148]

To commemorate the hurricane's 100th anniversary in 2000, the 1900 Storm Committee was established and began meeting in January 1998. The committee and then-Mayor of Galveston, Roger Quiroga, planned several public events in remembrance of the storm, including theatrical plays, an educational fundraising luncheon, a candlelight memorial service, a 5K run, the rededication of a commemorative Clara Barton plaque, and the dedication of the Place of Remembrance Monument.[149] At the dedication of the Place of Remembrance Monument, the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word sang "Queen of the Waves" and placed 10 roses and 90 other flowers around the monument to commemorate the 10 nuns and 90 children who perished after the hurricane destroyed the St. Mary's Orphans Asylum.[150] Speakers at the candlelight memorial service included U. S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, who was born in Galveston; Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration D. James Baker; and CBS Evening News anchor Dan Rather, who gained fame for his coverage during Hurricane Carla in 1961.[151] The Daily News published a special 100th anniversary commemorative edition newspaper on September 3, 2000.[149]

The last reported survivor of the Galveston hurricane of 1900, Maude Conic of Wharton, Texas,[152] died November 14, 2004, at the claimed age of 116, although the 1900 census and other records indicate she was about 10 years younger than that.[153]

The Galveston Historical Foundation maintains the Texas Seaport Museum at Pier 21 in the port of Galveston. Included in the museum is a documentary titled The Great Storm, that gives a recounting of the 1900 hurricane.[154][155]

See also

edit- History of Galveston, Texas

- Hurricane Ike (2008) - Took an extremely identical track in 2008 and devastated southeastern Texas.

- Hurricane Harvey (2017) - Took a similar track and devastated southeastern Texas.

- Hurricane Laura (2020) — Took a nearly identical track in 2020.

- 1775 Newfoundland hurricane – Deadliest Canadian hurricane on record

- Great Hurricane of 1780 – Deadliest Atlantic hurricane recorded

- 1959 Mexico hurricane – The deadliest hurricane in Mexico

- 1970 Bhola cyclone – The deadliest tropical cyclone on record, worldwide

- Isaac's Storm – Erik Larson's non-fiction book recounting the hurricane and the life of Galveston meteorologist Isaac Cline

- "Wasn't That a Mighty Storm" – An American folk song about the 1900 Galveston hurricane, later popularized by musicians such as Eric Von Schmidt and Tom Rush

- A Weekend in September - Nonfiction book about the hurricane

Notes

edit- ^ In local time, Central Standard Time (CST), the hurricane made landfall in Texas around 8:00 p.m. on September 8. However, government meteorological agencies such as NOAA use Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which is six hours ahead of CST.[5][6]

- ^ All damage figures pertaining to the United States are in 1900 USD, unless otherwise noted

- ^ All damage figures pertaining to Canada are in 1900 CAD, unless otherwise noted

- ^ The Canadian dollar and United States dollar were roughly identical in value between January 1879 and August 1914.[7]

- ^ However, that view was not universally held by all Texas residents, particularly those advocating other Texas seaports. "Galveston Island, with all its boasted accumulation of people, habitations, wealth, trade and commerce, is but a waif of the ocean, a locality but of yesterday ... liable, at any moment, and certain, at no distant day, of being engulfed and submerged by the self-same power that gave it form. Neither is it possible for all the skillful devices of mortal man to protect this doomed place against the impending danger; the terrible power of a hurricane cannot be ... resisted. I should as soon think of founding a city on an iceberg." – D. E. E. Braman (1857).[22]

- ^ The storm category color indicates the intensity of the hurricane when landfalling in the U.S.

References

edit- ^ a b Trumbla, Ron (May 12, 2017). "The Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900". NOAA Celebrates 200 Years of Science, Service and Stewardship. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Rhor, Monica (May 19, 2016). "Great Storm of 1900 brought winds of change". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Stephens, Sara G. (December 31, 2012). "Portrait of a Legend: The Great Storm of 1900: St. Mary's Orphan Asylum". Houston Family Magazine. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ "NOAA Press Release". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "1900 Major Hurricane Not_Named (1900239N15318)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Central Standard Time Zone – CST". WorldTimeServer.com. November 14, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Powell, James (December 2005). "A History of the Canadian Dollar" (PDF). Bank of Canada. p. 97. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Frank, p. 130.

- ^ "Ship-based Observations". Hurricanes: Science and Society. University of Rhode Island. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Partagás, José Fernández (1997). Year 1900 (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 97, 99, 105–106. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Roker, Al (September 4, 2015). "Blown Away: Galveston Hurricane, 1900". American History Magazine. HistoryNet. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ a b Larson, p. 83.

- ^ Frank, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e f Cline, Isaac M. (September 23, 1900). Special Report on The Galveston Hurricane of September 8, 1900. Weather Bureau (Report). Galveston, Texas. as archived in Garriott, Edward B. (September 1900). "West Indian Hurricane of September 1–12, 1900" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 28 (9): 372–374. Bibcode:1900MWRv...28..371G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1900)28[371b:WIHOS]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Frank, p. 136.

- ^ "Isaac's Storm: A Man, A Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History". Galveston County Daily News. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ Texas Almanac: City Population History from 1850–2000 (PDF) (Report). Texas Almanac. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Galveston marks anniversary of disaster". Longview News-Journal. Longview, Texas. Associated Press. September 9, 2000. p. 4A. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Babineck, Mark (September 4, 2000). "A century ago, hurricane left thousands dead". Star-Gazette. Elmira, New York. Associated Press. p. 5A. Retrieved April 18, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sealy, Edward Coyle (July 7, 2017). "Galveston Wharves". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ Nguyen, Tuan C. (November 7, 2007). "The 10 Worst U.S. Natural Disasters". Live Science. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Braman, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Heidorn, Keith C. (September 1, 2000). "Weather people and history: Dr Isaac M. Cline: A Man of Storm and Floods – Part 2". The Weather Doctor. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Graczyk, Michael L. (November 16, 1986). "Town Abandoned After 2 Hurricanes: Ruins Mark Once-Busy Texas Port". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ Frantz, Helen B. (January 19, 2008). "Handbook of Texas Online: Indianola Hurricanes". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved November 27, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Roth, David M. (January 6, 2010). Texas Hurricane History (PDF) (Report). Camp Springs, Maryland: National Weather Service. p. 47. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Zalzal, Kate S. (September 8, 2016). "Benchmarks: September 8, 1900: Massive hurricane strikes Galveston, Texas". Earth Magazine. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ "Weather Indications". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. September 5, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved June 2, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fair Tonight". Evening Star. Washington, D.C. September 6, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved June 2, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The Galveston Hurricane of 1900". EyeWitnesstoHistory.com. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Weems, John Edward (March 21, 2016). "Galveston Hurricane of 1900". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- ^ a b "The 1900 Storm: An Island Washed Away". Galveston County Daily News. Archived from the original on January 24, 2001. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ^ Cline, p. 49.

- ^ a b Larson, p. 103.

- ^ Moore, Nolan (July 15, 2014). "10 Tragic Stories About America's Deadliest Disaster". ListVerse. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ Larson, p. 12.

- ^ "Destructive Storm in Jamaica". Chicago Tribune. September 8, 1900. p. 9. Retrieved September 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Garriott, Edward B. (September 1900). "West Indian Hurricane of September 1–12, 1900" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 28 (9): 376. Bibcode:1900MWRv...28..371G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1900)28[371b:WIHOS]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ "Bad Storm In Santiago". Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, The Evening News. September 4, 1900. p. 2. Retrieved September 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Cyclone in Cuba". The New York Times. September 7, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved February 14, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Blake, Eric S; Landsea, Christopher W; Gibney, Ethan J (August 10, 2011). The deadliest, costliest and most intense United States tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts) (PDF) (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 47. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ^ "Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico" (PDF). Milken Institute of Public Health. August 27, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c National Climatic Data Center, National Hurricane Center (August 10, 2011). "The deadliest, costliest and most intense United States tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts)" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 47. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ^ Meyer, Ava (August 29, 2018). "Five deadliest hurricanes as toll from Hurricane Maria raised". Thomson Reuters Foundation News. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- ^ "Deadly storm came with little warning". Houston Chronicle. December 17, 2007. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Estimated Losses". Houston Post. September 13, 1900. p. 4. Retrieved February 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2018. p. 2. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Little, Becky (April 12, 2019). "How the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 Became the Deadliest U.S. Natural Disaster". The History Channel. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ "The Death List". Anaconda Standard. September 13, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved May 2, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Many Wrecks On Florida Coast". The New York Times. September 8, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved April 13, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Schoner, R. W.; Molansky, S. (July 1956). National Hurricane Research Project No. 3: Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (and Other Tropical Disturbances) (PDF) (Report). United States Department of Commerce. p. 248. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ "Coast Storm Does Damage". Natchez Democrat. September 7, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved August 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "At Pass Christian". The Semi-Weekly Times-Democrat. New Orleans, Louisiana. September 11, 1900. p. 12. Retrieved August 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Fierce Gale". The Semi-Weekly Times-Democrat. New Orleans, Louisiana. September 11, 1900. p. 12. Retrieved August 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Roth, David M. (April 8, 2010). Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF) (Report). Camp Springs, Maryland: National Weather Service. p. 28. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ "Rice Crop Damaged". The Semi-Weekly Times-Democrat. New Orleans, Louisiana. September 11, 1900. p. 12. Retrieved September 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Farmers Lose Heavily". The Semi-Weekly Times-Democrat. New Orleans, Louisiana. September 11, 1900. p. 12. Retrieved September 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Two Lives Lost". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans. September 8, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved September 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Storm Spends Its Fierce Fury". The Times-Democrat. New Orleans. September 9, 1900. p. 2. Retrieved September 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Huge Wave From the Gulf". El Paso Herald. September 10, 1900. p. 5. Retrieved February 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Summary of Storm News". Victoria Advocate. Victoria, Texas. September 15, 1900. p. 2. Retrieved February 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Eight Dead at Chenango". Chicago Tribune. September 10, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved February 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Houston Suffered From Storm". Houston Post. September 10, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved February 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Hhuston [sic] A Mass Of Wreckage". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. September 11, 1900. p. 4. Retrieved February 12, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bixel, p. 20.

- ^ Larson, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Olafson, Steve (August 28, 2000). "Unimaginable devastation: Deadly storm came with little warning". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ^ Larson, p. 136.

- ^ September Normals, Means and Extremes for Galveston (Report). National Weather Service Houston/Galveston, Texas. 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Ramos, Mary G. (2008). "After the Great Storm: Galveston's response to the hurricane of 1900". Texas Almanac. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Map of Galveston, Showing Destruction By The Storm". Houston Post. September 27, 1900. p. 7. Retrieved December 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Turner, Elizabeth Hayes. "Clara Barton and the Formation of Public Policy in Galveston, 1900" (PDF). University of Houston–Downtown. pp. 3–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- ^ Burnett, John (November 30, 2017). "The Tempest At Galveston: 'We Knew There Was A Storm Coming, But We Had No Idea'". NPR. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- ^ Baker, James Graham; Southwestern Historical Quarterly Vol CXIII; April 2010

- ^ "Galveston Hurricane of 1900 - Panoramic View of Tremont Hotel". The Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "History of The Grand". The Grand 1894 Opera House. Archived from the original on January 2, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Property Loss". Pittsburgh Daily Post. March 10, 1901. p. 20. Retrieved December 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Sisters of Charity Orphanage". Galveston County Daily News. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "The Strand". Galveston.com & Company, Inc. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ "Galveston May be Wiped Out By Storm". The New York Times. September 9, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved May 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ousley, p. 276.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Brian K.; Korose, Tom (September 12, 2008). "Hurricane Ike Set to Slam Texas Coast; Thousands Flee". New York: Bloomberg News.

- ^ a b Larson, p. 160.

- ^ a b Coe, p. 28.

- ^ Larson, p. 146.

- ^ Charles Coghian's Body Missing. - New York Times - 25 September 1900; pg. 2;

- ^ "Storm Reached Oklahoma". Leavenworth Times. September 11, 1900. p. 8. Retrieved September 3, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "One Killed at St. Joseph". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. September 12, 1900. p. 2. Retrieved September 3, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Chicago Badly Damaged". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. September 12, 1900. p. 2. Retrieved September 3, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wilson, W. M. (September 1900). Report for September, 1900 (PDF) (Report). Climatological Data. Vol. 5. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Climate and Crop Service of the Weather Bureau. pp. 3–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2023 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- ^ "Twin Cities Visited". St. Louis Dispatch. September 12, 1900. p. 2. Retrieved February 2, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Storm in Michigan". The Times Herald. Port Huron, Michigan. September 12, 1900. p. 8. Retrieved February 2, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Explore Shipwrecks: John B. Lyon". Ohio State University's Sea Grant College Program. Archived from the original on August 31, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Water Driven from Toledo Harbor and Vessels Stuck in the Mud". The Cincinnati Enquirer. September 13, 1900. p. 2. Retrieved November 18, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Great Damage By The Storm In Buffalo". Buffalo Courier. September 13, 1900. p. 7. Retrieved January 31, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lifted Derricp [sic] From The Ground". Buffalo Courier. September 13, 1900. p. 7. Retrieved January 31, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Cast House Was Blown Down". Buffalo Courier. September 13, 1900. p. 7. Retrieved January 31, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Exposition's Loss Hard to Estimate". Buffalo Courier. September 13, 1900. p. 7. Retrieved January 31, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Havoc Caused at Nearby Resorts". Buffalo Courier. September 13, 1900. p. 7. Retrieved January 31, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Course of the Hurricane". The New York Times. September 13, 1900. p. 14. Retrieved February 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "City swept by high winds". The New York Times. September 13, 1900. p. 14. Retrieved February 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Water High at The Battery". The New York Times. September 13, 1900. p. 14. Retrieved February 11, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Storm in Brooklyn". The New York Times. September 13, 1900. p. 14. Retrieved February 11, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Connecticut Fruit Crop Gone". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved November 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Wind Broke Up Fairs". Hartford Courant. September 14, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved November 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Storm at Westbrook". Hartford Courant. September 14, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved November 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Damage at Providence". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved November 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Death Near to Many". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved November 24, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Death Near to Many". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 2. Retrieved November 24, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Everett Was Hit Hard". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved November 30, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Many Accidents in Cambridge". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved November 30, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Water Sweeps High on The Cape". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved November 30, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Joseph W. Smith Drowned". The Boston Globe. September 14, 1900. p. 7. Retrieved May 17, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Schooner Sunk". The Burlington Free Press. September 13, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved November 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Damage From Wind Storm". The Chelsea Herald. Randolph, Vermont. September 20, 1900. p. 5. Retrieved November 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Storm Strikes in Burlington". Montpelier Evening Argus. September 12, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved November 19, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Roofs Flying In Air". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved November 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Manchester Feels Its Fury". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved November 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Biddeford Feels the Wind". The Boston Globe. September 13, 1900. p. 3. Retrieved May 9, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rappaport, Edward N; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose (January 1995). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492 – 1994 (PDF) (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-47). United States National Hurricane Center. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ a b "1900-1". Environment and Climate Change Canada. November 20, 2009. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Weinkle, Jessica; et al. (2018). "Normalized hurricane damage in the continental United States 1900–2017". Nature Sustainability. 1: 808–813. doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0165-2.

- ^ Wildmoon, K. C. (September 8, 2008). "Hurricane destroyed Galveston in 1900". CNN. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Van Riper, A. Bowdoin. "The Great Galveston hurricane of 1900". The Ultimate History Project. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities – Galveston, Texas". Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census Bureau History: 1900 Galveston Hurricane". United States Census Bureau. September 2015. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "William March Rice and His Legacy". The Historical Society at Sam Houston Park. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ a b Bixel, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b "Work of Committees". Pittsburgh Daily Post. March 10, 1901. p. 20. Retrieved February 14, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kramarae, p. 343.

- ^ Bixel, p. 74.

- ^ Bixel, p. 76.

- ^ a b "Some of the Contributions to the Relief Fund". The Topeka Daily Capital. September 15, 1900. p. 1. Retrieved February 14, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dittrick, Paula (July 29, 1991). "Galveston was 'The Ellis Island of the West'". United Press International. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ Larson, p. 161.

- ^ Sibley, Marilyn M. (March 28, 2017). "Houston Ship Channel". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "J.H.W. Stele to Sayers, September 11–12, 1900". Texas State Library and Archives Commission. March 30, 2011. Archived from the original on November 17, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ Rice, Bradley R. (June 12, 2010). "Commission Form of Government". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c Smith, Michael A. "Post-storm rebuilding considered 'Galveston's finest hour'". Galveston County Daily News. Archived from the original on February 16, 2001. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- ^ a b "Seawall". Galveston and Texas History Center, Rosenberg Library. October 21, 2004. Archived from the original on March 21, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Kline, Charles R. (June 15, 2010). "Robert, Henry Martyn". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 22, 2019.