Friedreich's ataxia (FRDA) is a rare, inherited, autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects the nervous system, causing progressive damage to the spinal cord, peripheral nerves, and cerebellum, leading to impaired muscle coordination (ataxia). The condition typically manifests in childhood or adolescence, with initial symptoms including difficulty walking, loss of balance, and poor coordination. As the disease progresses, it can also impact speech, vision, and hearing. Many individuals with Friedreich's ataxia develop scoliosis, diabetes, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a serious heart condition that is a leading cause of mortality in patients.

| Friedreich's ataxia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Spinocerebellar ataxia, FRDA, FA |

| |

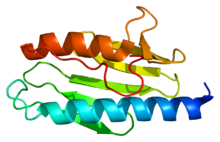

| Frataxin | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Neurology, Genetics |

| Symptoms | Muscle weakness, ataxia, fatigue, speech difficulties, scoliosis, heart disease, diabetes |

| Complications | Cardiomyopathy, scoliosis, diabetes |

| Usual onset | Childhood or adolescence |

| Duration | Long-term, progressive |

| Causes | Mutation in FXN gene |

| Risk factors | Family history (autosomal recessive inheritance) |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical evaluation, genetic testing, MRI, electromyography |

| Treatment | Symptom management, physical therapy, |

| Medication | Omaveloxolone |

| Prognosis | Progressive; reduced life expectancy |

| Frequency | 1 in 50,000 (United States) |

| Deaths | Often due to cardiac complications |

Friedreich's ataxia is caused by mutations in the FXN gene, which result in reduced production of frataxin, a protein essential for mitochondrial function, particularly in iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis. The deficiency of frataxin disrupts cellular energy production and leads to oxidative stress, contributing to the neurological and systemic symptoms associated with the disorder.

There is currently no cure for Friedreich's ataxia, but treatment focuses on symptom management and slowing disease progression. In 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Omaveloxolone as the first treatment for Friedreich's ataxia. This medication works by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation in neurons, which helps improve motor function in some patients. Ongoing research continues to explore potential therapies aimed at increasing frataxin levels, protecting mitochondria, and addressing the genetic cause of the disease. Although life expectancy may be reduced, particularly due to cardiac complications, advancements in care and treatment have improved outcomes for many individuals with Friedreich's ataxia.

Symptoms

editSymptoms typically start between the ages of 5 and 15, but in late-onset FRDA, they may occur after age 25 years.[1] The symptoms are broad, but consistently involve gait and limb ataxia, dysarthria and loss of lower limb reflexes.[1]

Classical symptoms

editThere is some variability in symptom frequency, onset and progression. All individuals with FRDA develop neurological symptoms, including dysarthria and loss of lower limb reflexes, and more than 90% present with ataxia.[1] Cardiac issues are very common with early onset FRDA .[1] Most individuals develop heart problems such as enlargement of the heart, symmetrical hypertrophy, heart murmurs, atrial fibrillation, tachycardia, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and conduction defects. Scoliosis is present in about 60%. 7% of people with FRDA also have diabetes and having diabetes has an adverse impact on people with FA, especially those that show symptoms when young.[2][3]

Other symptoms

editPeople who have been living with FRDA for a long time may develop other complications. 36.8% experience decreased visual acuity, which may be progressive and could lead to functional blindness.[3] Hearing loss is present in about 10.9% of cases.[3] Some patients report bladder and bowel symptoms.[4] Advanced stages of disease are associated with supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, most commonly atrial fibrillation.[1]

Other later stage symptoms can include, cerebellar effects such as nystagmus, fast saccadic eye movements, dysmetria and loss of coordination (truncal ataxia, and stomping gait).[1] Symptoms can involve the dorsal column such as the loss of vibratory sensation and proprioceptive sensation.[1]

The progressive loss of coordination and muscle strength leads to the full-time use of a wheelchair. Most young people diagnosed with FRDA require mobility aids such as a cane, walker, or wheelchair by early 20s.[5] The disease is progressive, with increasing staggering or stumbling gait and frequent falling. By the third decade, affected people lose the ability to stand or walk without assistance and require a wheelchair for mobility.[6]

Early-onset cases

editNon-neurological symptoms such as scoliosis, pes cavus, cardiomyopathy and diabetes are more frequent among the early-onset cases.[1]

Genetics

editFRDA is an autosomal-recessive disorder that affects a gene (FXN) on chromosome 9, which produces an important protein called frataxin.[7]

In 96% of cases, the mutant FXN gene has 90–1,300 GAA trinucleotide repeat expansions in intron 1 of both alleles.[8] This expansion causes epigenetic changes and formation of heterochromatin near the repeat.[7] The length of the shorter GAA repeat is correlated with the age of onset and disease severity.[9] The formation of heterochromatin results in reduced transcription of the gene and low levels of frataxin.[10] People with FDRA might have 5-35% of the frataxin protein compared to healthy individuals. Heterozygous carriers of the mutant FXN gene have 50% lower frataxin levels, but this decrease is not enough to cause symptoms.[11]

In about 4% of cases, the disease is caused by a (missense, nonsense, or intronic) point mutation, with an expansion in one allele and a point mutation in the other.[12] A missense point mutation can have milder symptoms.[12] Depending on the point mutation, cells can produce no frataxin, nonfunctional frataxin, or frataxin that is not properly localized to the mitochondria.[13][14]

Pathophysiology

editFRDA affects the nervous system, heart, pancreas, and other systems.[15][16]

Degeneration of nerve tissue in the spinal cord causes ataxia.[15] The sensory neurons essential for directing muscle movement of the arms and legs through connections with the cerebellum are particularly affected.[15] The disease primarily affects the spinal cord and peripheral nerves.[medical citation needed]

The spinal cord becomes thinner and nerve cells lose some myelin sheath.[15] The diameter of the spinal cord is smaller than that of unaffected individuals mainly due to smaller dorsal root ganglia.[16] The motor neurons of the spinal cord are affected to a lesser extent than sensory neurons.[15] In peripheral nerves, a loss of large myelinated sensory fibers occurs.[15]

Structures in the brain are also affected by FRDA, notably the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum.[16] The heart often develops some fibrosis, and over time, develops left-ventricle hypertrophy and dilatation of the left ventricle.[16]

Frataxin

editThe exact role of frataxin remains unclear.[17] Frataxin assists iron-sulfur protein synthesis in the electron transport chain to generate adenosine triphosphate, the energy molecule necessary to carry out metabolic functions in cells. It also regulates iron transfer in the mitochondria by providing a proper amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to maintain normal processes.[18] One result of frataxin deficiency is mitochondrial iron overload, which damages many proteins due to effects on cellular metabolism.[19]

Without frataxin, the energy in the mitochondria falls, and excess iron creates extra ROS, leading to further cell damage.[18] Low frataxin levels lead to insufficient biosynthesis of iron–sulfur clusters that are required for mitochondrial electron transport and assembly of functional aconitase and iron dysmetabolism of the entire cell.[19]

Diagnosis

editBalance difficulty, loss of proprioception, an absence of reflexes, and signs of other neurological problems are common signs from a physical examination.[6][20] Diagnostic tests are made to confirm a physical examination such as electromyogram, nerve conduction studies, electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, blood tests for elevated glucose levels and vitamin E levels, and scans such as X-ray radiograph for scoliosis.[21] MRI and CT scans of brain and spinal cord are done to rule out other neurological conditions.[22] Finally, a genetic test is conducted to confirm.[22]

Other diagnoses might include Charcot-Marie-Tooth types 1 and 2, ataxia with vitamin E deficiency, ataxia-oculomotor apraxia types 1 and 2, and other early-onset ataxias.[23]

Management of Symptoms

editPhysicians and patients can reference the clinical management guidelines for Friedreich ataxia.[24] These guidelines are intended to assist qualified healthcare professionals in making informed treatment decisions about the care of individuals with Friedreich ataxia.[25]

Therapeutics

editOmaveloxolone

edit

Omaveloxolone, sold under the brand name Skyclarys, is a medication used for the treatment of Friedreich's ataxia.[26][27] It is taken by mouth.[26]

The most common side effects include an increase in alanine transaminase and an increase of aspartate aminotransferase, which can be signs of liver damage, headache, nausea, abdominal pain, fatigue, diarrhea and musculoskeletal pain.[27]

Omaveloxolone was approved for medical use in the United States in February 2023,[26][27][28][29][30] and in the European Union in February 2024.[31] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers it to be a first-in-class medication.[32]Rehabilitation

editPhysical therapists play a critical role in educating on correct posture, muscle use, and the identification and avoidance of features that aggravate spasticities such as tight clothing, poorly adjusted wheelchairs, pain, and infection.[33]

Physical therapy typically includes intensive motor coordination, balance, and stabilization training to preserve gains.[34] Low-intensity strengthening exercises are incorporated to maintain functional use of the upper and lower extremities.[34] Stretching and muscle relaxation exercises can be prescribed to help manage spasticity and prevent deformities.[34] Other physical therapy goals include increased transfer and locomotion independence, muscle strengthening, increased physical resilience, "safe fall" strategy, learning to use mobility aids, learning how to reduce the body's energy expenditure, and developing specific breathing patterns.[34] Speech therapy can improve voice quality.[35]

Devices

editWell-fitted orthoses can promote correct posture, support normal joint alignment, stabilize joints during walking, improve range of motion and gait, reduce spasticity, and prevent foot deformities and scoliosis.[5]

Functional electrical stimulation or transcutaneous nerve stimulation devices may alleviate symptoms.[5]

As progression of ataxia continues, assistive devices such as a cane, walker, or wheelchair may be required for mobility and independence. A standing frame can help reduce the secondary complications of prolonged use of a wheelchair.[36][37]

Managing Cardiac Involvement

editCardiac abnormalities can be controlled with ACE inhibitors such as enalapril, ramipril, lisinopril, or trandolapril, sometimes used in conjunction with beta blockers. Affected people who also have symptomatic congestive heart failure may be prescribed eplerenone or digoxin to keep cardiac abnormalities under control.[5]

Surgical Intervention

editSurgery may correct deformities caused by abnormal muscle tone. Titanium screws and rods inserted in the spine help prevent or slow the progression of scoliosis. Surgery to lengthen the Achilles tendon can improve independence and mobility to alleviate equinus deformity.[5] An automated implantable cardioverter-defibrillator can be implanted after a severe heart failure.[5]

Prognosis

editThe disease evolves differently in different people.[36] In general, those diagnosed at a younger age or with longer GAA triplet expansions tend to have more severe symptoms.[5]

Congestive heart failure and abnormal heart rhythms are the leading causes of death,[38] but people with fewer symptoms can live into their 60s or older.[22]

Epidemiology

editFRDA affects Indo-European populations. It is rare in East Asians, sub-Saharan Africans, and Native Americans.[39] FRDA is the most prevalent inherited ataxia, affecting approximately 1 in 40,000 with European descent.[15] Males and females are affected equally. The estimated carrier prevalence is 1:100.[5] A 1990–1996 study of Europeans calculated the incidence rate was 2.8:100,000.[40] The prevalence rate of FRDA in Japan is 1:1,000,000.[41]

FRDA follows the same pattern as haplogroup R1b. Haplogroup R1b is the most frequently occurring paternal lineage in Western Europe. FRDA and Haplogroup R1b are more common in northern Spain, Ireland, and France, rare in Russia and Scandinavia, and follow a gradient through central and eastern Europe. A population carrying the disease went through a population bottleneck in the Franco-Cantabrian region during the last ice age.[42]

History

editThe condition is named after the nineteenth century German pathologist and neurologist, Nikolaus Friedreich.[43] Friedreich reported the disease in 1863 at the University of Heidelberg.[44][45][46] Further observations appeared in a paper in 1876.[47]

Frantz Fanon wrote his medical thesis on FRDA, in 1951.[48]

A 1984 Canadian study traced 40 cases to one common ancestral couple arriving in New France in 1634.[49]

FRDA was first linked to a GAA repeat expansion on chromosome 9 in 1996.[50]

Society and culture

editThe Cake Eaters is a 2007 independent drama film that stars Kristen Stewart as a young woman with FRDA.[51]

The Ataxian is a documentary that tells the story of Kyle Bryant, an athlete with FRDA who completes a long-distance bike race in an adaptive "trike" to raise money for research.[52]

Dynah Haubert spoke at the 2016 Democratic National Convention about supporting Americans with disabilities.[53]

Geraint Williams in an athlete affected by FRDA who is known for scaling Mount Kilimanjaro in an adaptive wheelchair.[54]

Shobhika Kalra is an activist with FRDA who helped build over 1000 wheelchair ramps across the United Arab Emirates in 2018 to try to make Dubai fully wheelchair-friendly by 2020.[55]

Butterflies Still Fly is a 2023 film, based on a true story, directed by Joseph Nenci. Italo is a light-hearted journalist, darkened by a personal drama that distracts him from work. He encounters with Giorgia, a young girl suffering from Friedreich's Ataxia, who will change his life.

Comedienne Fiona Cauley has Friedrich's Ataxia and often uses her disability and wheelchair in her comedic routines.

Research

editThere is no cure for Friedreich's ataxia, and treatment development is directed toward slowing, stopping, or reversing disease progression. In 2019, Reata Pharmaceuticals reported positive results in a phase 2 trial of RTA 408 (Omaveloxolone or Omav) to target activation of a transcriptional factor, Nrf2.[56] Nrf2 is decreased in FRDA cells.[57][58][59][60]

There are several additional therapies in trial. Patients can enroll in a registry to make clinical trial recruiting easier. The Friedreich's Ataxia Global Patient Registry is the only worldwide registry of Friedreich's ataxia patients to characterize the symptoms and establish the rate of disease progression.[61] The Friedreich's Ataxia App is the only global community app which enables novel forms of research.[62]

As of May 2021, research continues along the following paths.

Improve mitochondrial function and reduce oxidative stress

edit- Vatiquinone is being developed by PTC Therapeutics. Vatiquinone is a para-benzoquinone and targets the NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (quinone 1) (NQO1) enzyme to increase the biosynthesis of glutathione.[63]

- Retrotope is advancing RT001. RT001 is a deuterated synthetic homologue of ethyl linoleate, an essential omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid which is one of the major components of lipid membranes, particularly in mitochondria. Oxidation damage might be reduced if the polyunsaturated fatty acids in the lipids were made more rigid and less susceptible to oxidation by the replacement of hydrogen atoms with the heavy hydrogen isotope deuterium.[64]

Modulation of frataxin controlled metabolic pathways

edit- Dimethyl fumarate has been shown to increase frataxin levels in FRDA cells, mouse models, and humans. DMF showed an 85% increase in frataxin expression over 3 months in multiple sclerosis .[65]

Frataxin replacements or stabilizers

edit- EPO mimetics are orally available peptide imitations of erythropoietin. They are small molecules erythropoietin receptor agonists designed to activate the tissue-protective erythropoietin receptor.[66][67]

- Etravirine, an antiviral drug used to treat HIV, was found in a drug repositioning screening to increase frataxin levels in peripheral cells.[68] Fratagene Therapeutics is developing a small molecule called RNF126 to inhibit an enzyme which degrades frataxin.[69]

Increase frataxin gene expression

edit- Resveratrol might improve mitochondrial function.[70]

- Nicotinamide (vitamin B3) was found effective in preclinical FRDA models and well tolerated.[11]

- An RNA-based approach might unsilence the FXN gene and increase the expression of frataxin. Non-coding RNA (ncRNA) could be responsible for directing the localized epigenetic silencing of the FXN gene.

- Lentivirus-mediated delivery of the FXN gene has been shown to increase frataxin expression and prevent DNA damage in human and mouse fibroblasts.[71]

- CRISPR Therapeutics received a grant from the Friedreich's Ataxia Research Alliance to investigate gene editing as a potential treatment for the disease in 2017.[72]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Cook A, Giunti P (2017). "Friedreich's ataxia: Clinical features, pathogenesis and management". British Medical Bulletin. 124 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldx034. PMC 5862303. PMID 29053830.

- ^ McCormick A, Farmer J, Perlman S, Delatycki M, Wilmot G, Matthews K, et al. (2017). "Impact of diabetes in the Friedreich ataxia clinical outcome measures study". Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 4 (9): 622–631. doi:10.1002/acn3.439. PMC 5590524. PMID 28904984.

- ^ a b c Reetz K, Dogan I, Hohenfeld C, Didszun C, Giunti P, Mariotti C, et al. (2018). "Nonataxia symptoms in Friedreich Ataxia" (PDF). Neurology. 91 (10): e917–e930. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006121. PMID 30097477. S2CID 51956258.

- ^ "Friedreich Ataxia Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Friedreich ataxia clinical management guidelines". Friedreich Ataxia Research Alliance (USA). 2014. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ a b Parksinson MH, Boesch S, Nachbauer W, Mariotti C, Giunti P (August 2013). "Clinical features of Friedreich's ataxia: classical and atypical phenotypes". Journal of Neurochemistry. 126 (Supplement 1): 103–17. doi:10.1111/jnc.12317. PMID 23859346.

- ^ a b Klockgether T (August 2011). "Update on degenerative ataxias". Current Opinion in Neurology. 24 (4): 339–45. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834875ba. PMID 21734495.

- ^ Clark E, Johnson J, Dong YN, Mercado-Ayon, Warren N, Zhai M, et al. (November 2018). "Role of frataxin protein deficiency and metabolic dysfunction in Friedreich ataxia, an autosomal recessive mitochondrial disease". Neuronal Signaling. 2 (4): NS20180060. doi:10.1042/NS20180060. PMC 7373238. PMID 32714592.

- ^ Dürr A, Cossee M, Agid Y, Campuzano V, Mignard C, Penet C, et al. (October 1996). "Clinical and genetic abnormalities in patients with Friedreich's ataxia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (16): 1169–75. doi:10.1056/nejm199610173351601. PMID 8815938.

- ^ Montermini L, Andermann E, Labuda M, Richter A, Pandolfo M, Cavalcanti F, et al. (August 1997). "The Friedreich ataxia GAA triplet repeat: premutation and normal alleles". Human Molecular Genetics. 6 (8): 1261–6. doi:10.1093/hmg/6.8.1261. PMID 9259271.

- ^ a b Bürk K (2017). "Friedreich Ataxia: current status and future prospects". Cerebellum & Ataxias. 4: 4. doi:10.1186/s40673-017-0062-x. PMC 5383992. PMID 28405347.

- ^ a b Cossée M, Dürr A, Schmitt M, Dahl N, Trouillas P, Allinson P, et al. (February 1999). "Friedreich's ataxia: point mutations and clinical presentation of compound heterozygotes". Annals of Neurology. 45 (2): 200–6. doi:10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<200::AID-ANA10>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 9989622. S2CID 24885238.

- ^ Lazaropoulos M, Dong Y, Clark E, Greeley NR, Seyer LA, Brigatti KW, et al. (August 2015). "Frataxin levels in peripheral tissue in Friedreich ataxia". Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 2 (8): 831–42. doi:10.1002/acn3.225. PMC 4554444. PMID 26339677.

- ^ Galea CA, Huq A, Lockhart PJ, Tai G, Corben LA, Yiu EM, et al. (March 2016). "Compound heterozygous FXN mutations and clinical outcome in friedreich ataxia". Annals of Neurology. 79 (3): 485–95. doi:10.1002/ana.24595. PMID 26704351. S2CID 26709558.

- ^ a b c d e f g Delatycki MB, Bidichandani SI (2019). "Friedreich ataxia- pathogenesis and implications for therapies". Neurobiology of Disease. 132: 104606. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104606. PMID 31494282. S2CID 201839487.

- ^ a b c d Hanson E, Sheldon M, Pacheco B, Alkubeysi M, Raizada V (2019). "Heart disease in Friedreich's ataxia". World Journal of Cardiology. 11 (1): 1–12. doi:10.4330/wjc.v11.i1.1. PMC 6354072. PMID 30705738.

- ^ Maio N, Jain A, Rouault TA (2020). "Mammalian iron–sulfur cluster biogenesis: Recent insights into the roles of frataxin, acyl carrier protein and ATPase-mediated transfer to recipient proteins". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 55: 34–44. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.11.014. PMC 7237328. PMID 31918395.

- ^ a b Sahdeo S, Scott BD, McMackin MZ, Jasoliya M, Brown B, Wulff H, et al. (December 2014). "Dyclonine rescues frataxin deficiency in animal models and buccal cells of patients with Friedreich's ataxia". Human Molecular Genetics. 23 (25): 6848–62. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu408. PMC 4245046. PMID 25113747.

- ^ a b "Role of Frataxin, a Protein Implicated in Friedreich Ataxia, in Making Iron-Sulfur Clusters♦". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288 (52): 36787. 2013. doi:10.1074/jbc.P113.525857. PMC 3873538. S2CID 220291178.

- ^ Corben LA, Lynch D, Pandolfo M, Schulz JB, Delatycki MB, Clinical Management Guidelines Writing Group (November 2014). "Consensus clinical management guidelines for Friedreich ataxia". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 9: 184. doi:10.1186/s13023-014-0184-7. PMC 4280001. PMID 25928624.

- ^ Brigatti KW, Deutsch EC, Lynch DR, Farmer JM (September 2012). "Novel diagnostic paradigms for Friedreich ataxia". Journal of Child Neurology. 27 (9): 1146–51. doi:10.1177/0883073812448440. PMC 3674546. PMID 22752491.

- ^ a b c "Friedreich's Ataxia Fact Sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Friedreich ataxia NIH page". NIH Rare diseases. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ "FDRA Guidelines". Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Corben LA, Collins V, Milne S, Farmer J, Musheno A, Lynch D, et al. (2022). "Clinical management guidelines for Friedreich ataxia: Best practice in rare diseases". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 17 (1): 415. doi:10.1186/s13023-022-02568-3. PMC 9652828. PMID 36371255.

- ^ a b c "Skyclarys- omaveloxolone capsule". DailyMed. 12 May 2023. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "FDA approves first treatment for Friedreich's ataxia". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 February 2023. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2023. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Reata Pharmaceuticals Announces FDA Approval of Skyclarys (Omavaloxolone), the First and Only Drug Indicated for Patients with Friedreich's Ataxia". Reata Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Press release). 28 February 2023. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ Lee A (June 2023). "Omaveloxolone: First Approval". Drugs. 83 (8): 725–729. doi:10.1007/s40265-023-01874-9. PMID 37155124. S2CID 258567442. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Subramony SH, Lynch DL (May 2023). "A Milestone in the Treatment of Ataxias: Approval of Omaveloxolone for Friedreich Ataxia". Cerebellum. 23 (2): 775–777. doi:10.1007/s12311-023-01568-8. PMID 37219716. S2CID 258843532.

- ^ "Skyclarys EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 14 December 2023. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ New Drug Therapy Approvals 2023 (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Report). January 2024. Archived from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Aranca TV, Jones TM, Shaw JD, Staffetti JS, Ashizawa T, Kuo SH, et al. (February 2016). "Emerging therapies in Friedreich's ataxia". Neurodegenerative Disease Management. 6 (1): 49–65. doi:10.2217/nmt.15.73. PMC 4768799. PMID 26782317.

- ^ a b c d Chien H, Barsottini O (10 December 2016). Chien HF, Barsottini OG (eds.). Movement Disorders Rehabilitation. Springer, Cham. pp. 83–95. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46062-8. ISBN 978-3-319-46062-8.

- ^ Lowit A, Egan A, Hadjivassiliou M (2020). "Feasibility and Acceptability of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment in Progressive Ataxias". The Cerebellum. 19 (5): 701–714. doi:10.1007/s12311-020-01153-3. PMC 7471180. PMID 32588316.

- ^ a b Ojoga F, Marinescu S (2013). "Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation for Ataxic Patients" (PDF). Balneo Research Journal. 4 (2): 81–84. doi:10.12680/balneo.2013.1044.

- ^ Leonardi L, Aceto MG, Marcotulli C, Arcuria G, Serrao M, Pierelli F, et al. (March 2017). "A wearable proprioceptive stabilizer for rehabilitation of limb and gait ataxia in hereditary cerebellar ataxias: a pilot open-labeled study". Neurological Sciences. 38 (3): 459–463. doi:10.1007/s10072-016-2800-x. PMID 28039539. S2CID 27569800.

- ^ Doğan-Aslan M, Büyükvural-Şen S, Nakipoğlu-Yüzer GF, Özgirgin N (September 2018). "Demographic and clinical features and rehabilitation outcomes of patients with Friedreich ataxia: A retrospective study" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 64 (3): 230–238. doi:10.5606/tftrd.2018.2213. PMC 6657791. PMID 31453516. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ Vankan P (2013). "Prevalence gradients of Friedreich's Ataxia and R1b haplotype in Europe co-localize, suggesting a common Palaeolithic origin in the Franco-Cantabrian ice age refuge". Journal of Neurochemistry. 126: 11–20. doi:10.1111/jnc.12215. PMID 23859338.

- ^ Dürr A, Cossee M, Agid Y, Campuzano V, Mignard C, Penet C, et al. (October 1996). "Clinical and genetic abnormalities in patients with Friedreich's ataxia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (16): 1169–75. doi:10.1056/NEJM199610173351601. PMID 8815938.

- ^ Kita K (December 1993). "[Spinocerebellar degeneration in Japan--the feature from an epidemiological study]". Rinsho Shinkeigaku = Clinical Neurology. 33 (12): 1279–84. PMID 8174325.

- ^ Vankan P (August 2013). "Prevalence gradients of Friedreich's ataxia and R1b haplotype in Europe co-localize, suggesting a common Palaeolithic origin in the Franco-Cantabrian ice age refuge". Journal of Neurochemistry. 126 (Suppl 1): 11–20. doi:10.1111/jnc.12215. PMID 23859338. S2CID 39343424.

- ^ Nicolaus Friedreich at Who Named It?

- ^ Friedreich N (1863). "Ueber degenerative Atrophie der spinalen Hinterstränge" [About degenerative atrophy of the spinal posterior column]. Arch Pathol Anat Phys Klin Med (in German). 26 (3–4): 391–419. doi:10.1007/BF01930976. S2CID 42991858.

- ^ Friedreich N (1863). "Ueber degenerative Atrophie der spinalen Hinterstränge" [About degenerative atrophy of the spinal posterior column]. Arch Pathol Anat Phys Klin Med (in German). 26 (5–6): 433–459. doi:10.1007/BF01878006. S2CID 34515886.

- ^ Friedreich N (1863). "Ueber degenerative Atrophie der spinalen Hinterstränge" [About degenerative atrophy of the spinal posterior column]. Arch Pathol Anat Phys Klin Med (in German). 27 (1–2): 1–26. doi:10.1007/BF01938516. S2CID 46459932.

- ^ Friedreich N (1876). "Ueber Ataxie mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der hereditären Formen" [About ataxia with special reference to hereditary forms]. Arch Pathol Anat Phys Klin Med (in German). 68 (2): 145–245. doi:10.1007/BF01879049. S2CID 42155823.

- ^ Adam Shatz, "Where Life Is Seized" Archived 12 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, London Review of Books, 19 January 2017

- ^ Barbeau A, Sadibelouiz M, Roy M, Lemieux B, Bouchard JP, Geoffroy G (November 1984). "Origin of Friedreich's disease in Quebec". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 11 (4 Suppl): 506–9. doi:10.1017/S0317167100034971. PMID 6391645.

- ^ Campuzano V, Montermini L, Moltò MD, Pianese L, Cossée M, Cavalcanti F, et al. (March 1996). "Friedreich's ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion". Science. 271 (5254): 1423–7. Bibcode:1996Sci...271.1423C. doi:10.1126/science.271.5254.1423. PMID 8596916. S2CID 20303793.

- ^ Holden S (13 March 2009). "The Cake Eaters". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ "Devastating Diagnosis Pushes Local Man To Live Bigger". CBS Sacramento. 30 May 2015. Archived from the original on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "How the DNC Is Subtly Rebuking Donald Trump's Mockery of a Disabled Reporter". Slate. 27 July 2016. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Man with rare nerve condition climbs Mount Kilimanjaro to raise money for charity". ITV. 25 November 2018. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Shobhika Kalra: Meet the Dubai woman in wheelchair who helped build 1,000 ramps across UAE". GULF NEWS. 30 October 2018. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ Reisman SA, Lee CY, Meyer CJ, Proksch JW, Sonis ST, Ward KW (May 2014). "Topical application of the synthetic triterpenoid RTA 408 protects mice from radiation-induced dermatitis". Radiation Research. 181 (5): 512–20. Bibcode:2014RadR..181..512R. doi:10.1667/RR13578.1. PMID 24720753. S2CID 23906747.

- ^ Shan Y, Schoenfeld RA, Hayashi G, Napoli E, Akiyama T, Iodi Carstens M, et al. (November 2013). "Frataxin deficiency leads to defects in expression of antioxidants and Nrf2 expression in dorsal root ganglia of the Friedreich's ataxia YG8R mouse model". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 19 (13): 1481–93. doi:10.1089/ars.2012.4537. PMC 3797453. PMID 23350650..

- ^ "A Phase 2 Study of the Safety, Efficacy, and Pharmacodynamics of RTA 408 in the Treatment of Friedreich's Ataxia (MOXIe)". 1 October 2020 – via clinicaltrials.gov.

- ^ "FARA – Part 2 of the Phase II MOXIe study (RTA 408 or omaveloxolone)". www.curefa.org. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Lynch DR, Farmer J, Hauser L, Blair IA, Wang QQ, Mesaros C, et al. (January 2019). "Safety, pharmacodynamics, and potential benefit of omaveloxolone in Friedreich ataxia". Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 6 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1002/acn3.660. PMC 6331199. PMID 30656180.

- ^ "FA Global Patient Registry (FAGPR)". FA Global Patient Registry (FAGPR). 5 October 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ "The FA App". The FA App). Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Enns GM, Kinsman SL, Perlman SL, Spicer KM, Abdenur JE, Cohen BH, et al. (January 2012). "Initial experience in the treatment of inherited mitochondrial disease with EPI-743". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 105 (1): 91–102. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.10.009. PMID 22115768.

- ^ Indelicato E, Bosch S (2018). "Emerging therapeutics for the treatment of Friedreich's ataxia". Expert Opinion on Orphan Drugs. 6: 57–67. doi:10.1080/21678707.2018.1409109. S2CID 80157839.

- ^ Jasoliya M, Sacca F, Sahdeo S, Chedin F, Pane C, Brescia Morra V, et al. (June 2019). "Dimethyl fumarate dosing in humans increases frataxin expression: A potential therapy for Friedreich's Ataxia". PLOS ONE. 14 (6): e0217776. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1417776J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217776. PMC 6546270. PMID 31158268.

- ^ Miller JL, Rai M, Frigon NL, Pandolfo M, Punnonen J, Spencer JR (September 2017). "Erythropoietin and small molecule agonists of the tissue-protective erythropoietin receptor increase FXN expression in neuronal cells in vitro and in Fxn-deficient KIKO mice in vivo". Neuropharmacology. 123: 34–45. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.05.011. PMID 28504123. S2CID 402724.

- ^ "STATegics, Inc. Announces a New Grant from Friedreich's Ataxia Research Alliance" (PDF).

- ^ Alfedi G, Luffarelli R, Condò I, Pedini G, Mannucci L, Massaro DS, et al. (March 2019). "Drug repositioning screening identifies etravirine as a potential therapeutic for friedreich's ataxia". Movement Disorders. 34 (3): 323–334. doi:10.1002/mds.27604. PMID 30624801. S2CID 58567610.

- ^ Benini M, Fortuni S, Condò I, Alfedi G, Malisan F, Toschi N, et al. (February 2017). "E3 Ligase RNF126 Directly Ubiquitinates Frataxin, Promoting Its Degradation: Identification of a Potential Therapeutic Target for Friedreich Ataxia". Cell Reports. 18 (8): 2007–2017. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.079. PMC 5329121. PMID 28228265.

- ^ "Jupiter Orphan Therapeutics, Inc. Enters into a Global Licensing Agreement with Murdoch Childrens Research Institute" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Khonsari H, Schneider M, Al-Mahdawi S, Chianea YG, Themis M, Parris C, et al. (December 2016). "Lentivirus-meditated frataxin gene delivery reverses genome instability in Friedreich ataxia patient and mouse model fibroblasts". Gene Therapy. 23 (12): 846–856. doi:10.1038/gt.2016.61. PMC 5143368. PMID 27518705.

- ^ Melão A (19 October 2017). "CRISPR Therapeutics Receives FARA Grant to Develop Gene Editing Therapies for Friedreich's Ataxia". Friedreich's Ataxia News. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.