Forrest City is a city in St. Francis County, Arkansas, United States, and the county seat.[3] It was named for General Nathan Bedford Forrest, a notable Confederate war hero who later became the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Shortly after the end of the Civil War, he had a construction crew camped here, who were completing a railroad between Memphis and Little Rock. The population was 15,371 at the 2010 census, an increase from 14,774 in 2000. The city identifies as the "Jewel of the Delta".[4]

Forrest City, Arkansas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Motto(s): One Forrest City, moving forward, one step at a time | |

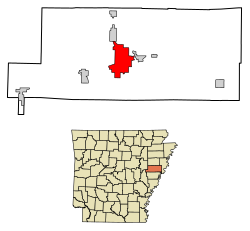

Location of Forrest City in St. Francis County, Arkansas | |

| Coordinates: 35°00′20″N 90°47′19″W / 35.00556°N 90.78861°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arkansas |

| County | St. Francis |

| Area | |

• Total | 20.31 sq mi (52.60 km2) |

| • Land | 20.25 sq mi (52.43 km2) |

| • Water | 0.07 sq mi (0.17 km2) |

| Elevation | 249 ft (76 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 13,015 |

| • Density | 642.87/sq mi (248.22/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code | 72335 |

| FIPS code | 05-24430 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2403637[2] |

| Website | cityofforrestcityar |

History

edit19th century

editOn October 13, 1827, St. Francis County, located in the east central part of Arkansas, was officially organized by the Arkansas Territorial Legislature in Little Rock.

Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate General and later the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, became interested in the area around Crowley's Ridge during the American Civil War. In 1866, General Forrest and C. C. McCreanor contracted to finish the Memphis & Little Rock Railroad from Madison located on the St. Francis River to DeValls Bluff on the west bank of the White River. The route traversed the challenging Crowley's Ridge and L'Anguille River bottoms. In 1868, train service through Forrest City was established.

Forrest later built a commissary on Front Street. Colonel V.B. Izard began the task of designing the town at the same time. Most residents were calling the area "Forrest's Town," which was later named Forrest City and was incorporated on May 11, 1870.

The county seat was initially located in the now defunct town of Franklin until 1840, when it was moved to Madison. In 1855 it was moved to Mount Vernon where the court house burned in 1856 destroying county records. This prompted a move back to Madison. The county seat was moved to Forrest City in 1874, where the courthouse was assigned to a wooden structure. When it burned shortly thereafter, county records were again destroyed.

In 1889, the city was the site of a white race riot that resulted in their expulsion of African American leaders.

20th century

editThe Imperial Council of Jugamos, a fraternal organization of African Americans founded in 1910 by Wallace Leon Purifoy had its headquarters in Forrest City.[5] The Forrest City Herald printed its constitution in 1916.[6] The New Castle Herald noted the group and its officers in 1919.[7]

In 1940, Forrest City was a stop for the Choctaw Rocket, a passenger train operated by the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad. Service was discontinued in 1964. Evidence that giant mastodons roamed the slope was revealed in 1949 when workmen excavating for sewer improvements found bones of the massive beasts within the city limits.

In 1988, Forrest City High School held its first integrated prom. After school integration was ordered in the mid-1960s, Forrest City eliminated school-sponsored dances and social activities. For 23 years, social clubs and individual families had organized a racially segregated prom.[8]

21st century

editIn 2018, the city elected Cedric Williams as mayor; Williams is the third African American mayor in the city's history.[9]

Geography

editAccording to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 16.3 square miles (42 km2), 16.2 square miles (42 km2) of which is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) (0.37%) of which is water.

Forrest City is located on Crowley's Ridge, a geological phenomenon that rises above the flat Mississippi Delta terrain that surrounds it. This north-south running highland is some three miles wide and 300 feet above sea level. Several species of trees not indigenous to Arkansas are found here, including beech, butternut, sugar maple, and cucumber trees.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 903 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,021 | 13.1% | |

| 1900 | 1,361 | 33.3% | |

| 1910 | 2,484 | 82.5% | |

| 1920 | 3,377 | 36.0% | |

| 1930 | 4,594 | 36.0% | |

| 1940 | 5,699 | 24.1% | |

| 1950 | 7,607 | 33.5% | |

| 1960 | 10,544 | 38.6% | |

| 1970 | 12,521 | 18.8% | |

| 1980 | 13,803 | 10.2% | |

| 1990 | 13,364 | −3.2% | |

| 2000 | 14,774 | 10.6% | |

| 2010 | 15,371 | 4.0% | |

| 2020 | 13,015 | −15.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White | 3,046 | 23.4% |

| Black or African American | 9,184 | 70.56% |

| Native American | 42 | 0.32% |

| Asian | 78 | 0.6% |

| Other/Mixed | 219 | 1.68% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 446 | 3.43% |

As of the 2020 U.S. census, there were 13,015 people, 4,358 households, and 2,655 families residing in the city.

Government and infrastructure

editThe Federal Bureau of Prisons Federal Correctional Complex, Forrest City is in Forrest City.[12][13]

The United States Postal Service operates the Forrest City Post Office.[14]

Woodruff Electric Cooperative, a non-profit rural electric utility cooperative, is headquartered in Forrest City.

Local landmarks

editThe Forrest City Chamber of Commerce is located in the 100-year-old Becker House. This house has served a variety of functions since being sold by the Becker family. It was an antique store and later a home furnishings boutique before being occupied by the Chamber.

Forrest City had five sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places including:

- Campbell House

- First United Methodist

- Forrest City High School (aka, "Old Central")

- Mann House

- Stuart Springs

Education

editForrest City School District operates public schools, including Forrest City High School.

Circa 2014 KIPP Delta established the grade 5-8 KIPP Forrest City College Preparatory School in Forrest City, which occupied several temporary buildings and a portion of a Catholic church which had a lease agreement with KIPP. In 2018 KIPP Delta asked the State of Arkansas for permission to close KIPP Forrest City and send students to the Helena-West Helena facility.[15]

Notable people

edit- Barrett Astin, former professional baseball player, Cincinnati Reds

- Little Buddy Doyle, blues guitarist, singer and songwriter

- Lewis P. Featherstone, former U.S. Representative[16]

- Al Green, singer and minister

- Willie Hale, rhythm and blues guitarist, singer and songwriter

- John W. Henry, principal owner, Boston Red Sox

- Chris Hicky, music video director

- Mark W. Izard, 3rd Governor of the Nebraska Territory

- Jason Jones, professional football player

- Don Kessinger, born in Forrest City, professional baseball player and manager.[17]

- Albert King, blues artist

- Henry Loeb, mayor of Memphis, Tennessee

- Cara McCollum, 2013 Miss New Jersey[18]

- Gilbert Morris, award-winning Christian author

- King Perry, jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, arranger, and bandleader

- Jimmy Rogers, football player

- Cal Slayton, comic book artist

- Vernon Sykes, member of Ohio House of Representatives

- Dwight Tosh, Republican member of the Arkansas House of Representatives

- Winston P. Wilson, U.S. Air Force Major General and Chief of the National Guard Bureau

- Dennis Winston, professional football player

- G. Wood, one of four actors to appear in both the 1970 film M*A*S*H and the television series M*A*S*H.

- Marshall Wright, former member of the Arkansas House of Representatives

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Forrest City, Arkansas

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Office of the Mayor". Archived from the original on October 28, 2011.

- ^ Richardson, Clement (June 7, 1919). "The National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race". National Publishing Company – via Google Books.

- ^ Jugamos, Imperial Council of (June 7, 1916). "Constitution and General Laws of the Imperial Council of Jugamos". Forrest City Herald Print – via Google Books.

- ^ "1919 - 01 15 -". January 15, 1919. p. 4 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ McIntosh, Barbara (May 2, 1988). "The Class That Crossed the Great Divide; In Arkansas, a High School's First Integrated Prom". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 18, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ Nix, Ryan (February 3, 2020). "Tide Is Turning: Black Mayors Popping Up Across Arkansas". Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Forrest City city, Arkansas[permanent dead link]." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on May 1, 2011.

- ^ "FCI Forrest City Medium Contact Information Archived January 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on May 1, 2011. "FCI FORREST CITY MEDIUM FEDERAL CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTION 1400 DALE BUMPERS ROAD FORREST CITY, AR 72335"

- ^ "Post Office Location - FORREST CITY Archived 2012-08-30 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 1, 2011.

- ^ Howell, Cynthia (December 2, 2018). "KIPP schools seek campus closure in Arkansas". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- ^ Welch, Melanie (2012). "Lewis Porter Featherstone (1851–1922)". Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture.

- ^ Reichler, Joseph L., ed. (1979) [1969]. The Baseball Encyclopedia (4th ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-578970-8.

- ^ Miller, Lindsey (June 18, 2013). "Forrest City Native Cara McCollum Wins Miss New Jersey". Arkansas Times.