The eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus) is a marsupial found in the eastern third of Australia, with a population of several million. It is also known as the great grey kangaroo and the forester kangaroo. Although a big eastern grey male can typically weigh up to 69 kg (152 lb) and have a length of well over 2 m (6 ft 7 in),[4] the scientific name, Macropus giganteus (gigantic large-foot), is misleading: the red kangaroo of the semi-arid inland is larger, weighing up to 90 kg (200 lb).

| Eastern grey kangaroo[1] Temporal range: Early Pliocene – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A female and joey at the Brunkerville | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Macropodidae |

| Genus: | Macropus |

| Species: | M. giganteus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Macropus giganteus Shaw, 1790

| |

| |

| Eastern grey kangaroo range | |

Taxonomy

editThe eastern grey kangaroo was described by George Shaw in 1790 as Macropus giganteus.

Subspecies

editWhile two subspecies were recognised by Mammal Species of the World (MSW),[1] there is some dispute as to the validity of this division, and the subspecies are not recognised by the Australian Mammal Society,[5] the IUCN,[2] or the American Society of Mammalogists, which produces the successor of the MSW.[6] Albert Sherbourne Le Souef created the Tasmanian subspecies in 1923, based on coat colour.[7] In 1972 Kirsch and Poole published a paper supporting the concept of separate species for the eastern and western greys, but casting doubt on the subspecies M. g. tasmaniensis, as

...these subspecies, or species as Le Souef (1923) would have it in the case of the Tasmanian forester, are based on so little study of so little material that we do not believe that they should be recognized as such at this time.[8]: 336

A later study published in 2003 was also critical of the division, stating that

Phylogenetic comparisons between M. g. giganteus and M. g. tasmaniensis indicated that the current taxonomic status of these subspecies should be revised as there was a lack of genetic differentiation between the populations sampled."[9]

The subspecies recognised by Mammal Species of the World were:

- Macropus giganteus giganteus – found in eastern and central Queensland, Victoria, New South Wales and southeastern South Australia

- Macropus giganteus tasmaniensis – (commonly known as the forester kangaroo) endemic to Tasmania

Description

editThe eastern grey kangaroo is the second largest and heaviest living marsupial and native land mammal in Australia. An adult male will commonly weigh around 50 to 66 kg (110 to 146 lb) whereas females commonly weigh around 17 to 40 kg (37 to 88 lb). They have a powerful tail that is over 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long in adult males.[10] Large males of this species are more heavily built and muscled than the lankier red kangaroo and can occasionally exceed normal dimensions. One of these, shot in eastern Tasmania weighed 82 kg (181 lb), with a 2.64 m (8 ft 8 in) total length from nose to tail (possibly along the curves). The largest known specimen, examined by Lydekker, had a weight of 91 kg (201 lb) and measured 2.92 m (9 ft 7 in) along the curves. When the skin of this specimen was measured it had a "flat" length of 2.49 m (8 ft 2 in).[11]

The eastern grey is easy to recognise: its soft grey coat is distinctive, and it is usually found in moister, more fertile areas than the red. Red kangaroos, though sometimes grey-blue in colour, have a totally different face than eastern grey kangaroos. Red kangaroos have distinctive markings in black and white beside their muzzles and along the sides of their face. Eastern grey kangaroos do not have these markings, and their eyes seem large and wide open.

Where their ranges overlap, it is much more difficult to distinguish between eastern grey and western grey kangaroos, which are closely related. They have a very similar body and facial structure, and their muzzles are fully covered with fine hair (though that is not obvious at a distance, their noses do look noticeably different from the noses of reds and wallaroos). The eastern grey's colouration is a light-coloured grey or brownish-grey, with a lighter silver or cream, sometimes nearly white, belly. The western grey is a dark dusty brown colour, with more contrast especially around the head.[12] Indigenous Australian names include iyirrbir (Uw Oykangand and Uw Olkola) and kucha (Pakanh).[13] The highest ever recorded speed of any kangaroo was 64 km/h (40 mph) set by a large female eastern grey kangaroo.[14]

-

adult M. g. tasmaniensis

-

juvenile M. g. tasmaniensis

-

female with joey M. g. tasmaniensis

Distribution and habitat

editAlthough the red is better known, the eastern grey is the kangaroo most often encountered in Australia, due to its adaptability. Few Australians visit the arid interior of the continent, while many live in and around the major cities of the southern and eastern coast, from where it is usually only a short drive to the remaining pockets of near-city bushland where kangaroos can be found without much difficulty.[15][16][17][18] The eastern grey prefers open grassland with areas of bush for daytime shelter and mainly inhabits the wetter parts of Australia.[19] It also inhabits coastal areas, woodlands, sub-tropical forests, mountain forests, and inland scrubs.[19]

Behaviour

editLike all kangaroos, it is mainly nocturnal and crepuscular,[12] and is mostly seen early in the morning, or as the light starts to fade in the evening.[20] In the middle of the day, kangaroos rest in the cover of the woodlands and eat there but then come out in the open to feed on the grasslands in large numbers.[12] The eastern grey kangaroo is predominantly a grazer, eating a wide variety of grasses, whereas some other species (e.g. the red kangaroo) include significant amounts of shrubs in their diet.

Eastern grey kangaroos are gregarious and form open-membership groups.[21] The groups contain an average of three individuals.[20] Smaller groups join to graze in preferred foraging areas, and to rest in large groups around the middle of the day.[20] They exist in a dominance hierarchy and the dominant individuals gain access to better sources of food and areas of shade.[12] However, kangaroos are not territorial. Eastern grey kangaroos adjust their behaviour in relation to the risk of predation with reproductive females, individuals on the periphery of the group and individuals in groups far from cover being the most vigilant.[21] Vigilance in individual kangaroos does not seem to significantly decrease when the size of the group increases. However, there is a tendency for the proportion of individuals on the periphery of the group to decline as group size increases.[21] The open membership of the group allows more kangaroos to join and thus provide more buffers against predators.[21]

-

Composite image of M. g. giganteus from Mount Annan, New South Wales

Reproduction

editEastern grey kangaroos are polygynous which means that one male mates with multiple females. Males do a lot of intraspecific competition for mates which includes male-male fights to determine dominance between the two males. When a dominant male finds a female in estrus, he will court the female and eventually they copulate.[22] After copulation, the male will guard the female from other males. This whole process from courting to when the male is done guarding the singular females is roughly an hour.[23]

Females may form strong kinship bonds with their relatives. Females with living female relatives have a greater chance of reproducing.[24] Most kangaroo births occur during the summer.[25] Eastern grey kangaroos are obligate breeders in that they can reproduce in only one kind of habitat.[26]

The female eastern grey kangaroo is usually permanently pregnant except on the day she gives birth; however, she has the ability to freeze the development of an embryo until the previous joey is able to leave the pouch. This is known as embryonic diapause, and will occur in times of drought and in areas with poor food sources. The composition of the milk produced by the mother varies according to the needs of the joey. Since lactation is very energy expensive, females that are lactating typically change some of their foraging habits. Some females will forage faster so they can tend to their joeys more, while others forage more aggressively so they can eat as much as possible.[27] In addition, the mother is able to produce two different kinds of milk simultaneously for the newborn and the older joey still in the pouch. Unusually, during a dry period, males will not produce sperm, and females will conceive only if there has been enough rain to produce a large quantity of green vegetation.[28] Females take care of the young without any assistance from the males. Female kangaroos with a joey often feed solitary in order to help separate themselves from the rest of the kangaroos in order to reduce predation.[29] The joeys are heavily reliant on their mothers for about 550 days, which is when they are weaned. Females sexually mature between 17 and 28 months, while males mature at around 25 months.[19]

-

M. g. tasmaniensis

-

female and joey interacting

-

female and joey browsing

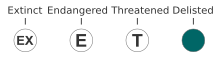

Status

editIt is popularly thought, but not confirmed by evidence,[30][31] that kangaroo populations have increased significantly since the European colonisation of Australia because of the increased areas of grassland (as distinct from forest), the reduction in dingo numbers, and the availability of artificial watering holes. The estimated population of the species Australia-wide in 2010 was 11.4 million.[32] In some places the eastern grey is so numerous it causes overgrazing and some individual populations have been culled in some parts of Australia (see, for example, the Eden Park Kangaroo Cull).[33][34][35] Despite the commercial harvest and some culls, the eastern grey remains common and widespread. Eastern greys are common in suburban and rural areas where they have been observed to form larger groups than in natural areas.[36] It still covers the entire range it occupied when Europeans arrived in Australia in 1788[37] and it often comes into conflict with agriculture as it uses the more fertile districts that now carry crops or exotic pasture grasses, which kangaroos readily eat.[38] Kangaroo meat has also been considered to replace beef in recent years, as their soft feet are preferable to hooves in erosion prone areas.[39]

References

edit- ^ a b Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Munny, P.; Menkhorst, P.; Winter, J. (2016). "Macropus giganteus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T41513A21952954. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T41513A21952954.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Species Profile".

- ^ "Discover the Fascinating Eastern Grey Kangaroo at Billabong Sanctuary". billabongsanctuary.com.au. Billabong Sanctuary. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "The AMTC Australian Mammal Species List. Version 4.1" (PDF). The Australian Mammal Society Inc. 2024. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ "Macropus giganteus G. K. Shaw, 1790". ASM Mammal Diversity Database. American Society of Mammalogists.

- ^ Le Souef, A.S. (1923). "The grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus), and its allies". Australian Zoologist. 3: 145–147.

- ^ Kirsch, J.A.W.; Poole, W.E. (1972). "Taxonomy and distribution of the grey kangaroos, Macropus giganteus Shaw and Macropus Fuliginosus (Desmarest), and their subspecies". Australian Journal of Zoology. 20 (3): 315–339. doi:10.1071/zo9720315.

- ^ Zenger, K.R.; Eldridge, M.D.B.; Cooper, D.W. (2003). "Intraspecific variation, sex-biased dispersal and phylogeography of the eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus)". Heredity. 91 (2): 153–162. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800293. PMID 12886282.

- ^ Green-Barber, J.; Ong, O.; Kanuri, A.; Stannard, H.; Old, J. (2017). "Blood constituents of free-ranging eastern grey kangaroos (Macropus giganteus)". Australian Mammalogy. 40 (2): 136–145. doi:10.1071/AM17002.

- ^ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ a b c d Dawson, Terence J. (1998). Kangaroos: Biology of the Largest Marsupials. Sydney, Australia: University of New South Wales Press. pp. 12–18. ISBN 0-86840-317-2.

- ^ Hamilton, Philip (5 July 1998). "eastern grey kangaroo, Macropus giganteus". Uw Oykangand and Uw Olkola Multimedia Dictionary. Kowanyama Land and Natural Resources Management Office. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ The Guinness Book of Records. 2004. p. 53.

- ^ "The Best Places to See Wild Kangaroos Near Sydney". Walk My World. 4 May 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "10 Best Places to See Wild Kangaroos near Melbourne". Walk My World. 20 February 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Wildlife in Brisbane – Top 10 Wild Native Australian Animals in Brisbane!". Brisbane Kids. 29 January 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "MELALEUCA BOARDWALK & KANGAROO TRAIL Coombabah Lakelands". Must Do Gold Coast. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Frith, H. J.; Calaby, J. H. (1969). Kangaroos. Melbourne, Australia: Cheshire Publishing. ASIN B0006BRQ7I.

- ^ a b c Green-Barber, J.; Old, J. (2018). "Is camera trap videography suitable for assessing activity patterns in eastern grey kangaroos?". Pacific Conservation Biology. 24 (2): 134–141. doi:10.1071/PC17051.

- ^ a b c d Colagross, A. M. L.; Cockburn, A. (1993). "Vigilance and grouping in the eastern grey kangaroo, Macropus giganteus". Australian Journal of Zoology. 41 (4): 325–334. doi:10.1071/ZO9930325.

- ^ Gelin, Uriel (29 September 2013). "Offspring sex, current and previous reproduction affect feeding behaviour in wild Eastern Grey Kangaroos. Animal behaviour". Animal Behaviour. 86 (5): 885–891. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.08.016.

- ^ Rioux-Paquette, Elise; Garant, Dany; Martin, Alexandre M.; Coulson, Graeme; Festa-Bianchet, Marco (2015). "Paternity in eastern grey kangaroos: moderate skew despite strong sexual dimorphism". Behavioral Ecology. 26 (4): 1147–1155. doi:10.1093/beheco/arv052. ISSN 1045-2249.

- ^ Jarman, P.J. (1993). "Individual behavior and social organisation of kangaroos". Physiology and Ecology. 29: 70–85.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, T. H. (1965). "Studies of Macropodidae in Queensland. 1. Food preferences of the grey kangaroo (Macropus major Shaw)". Queensland Journal of Agricultural and Animal Science. 22: 89–93.

- ^ Lee, A. K.; Cockburn, A. (1985). Evolutionary Ecology of Marsupials. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511661693. ISBN 9780511661693.

- ^ Montana, Luca; King, Wendy J.; Coulson, Graeme; Garant, Dany; Festa-Bianchet, Marco (1 June 2022). "Large eastern grey kangaroo males are dominant but do not monopolize matings". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 76 (6): 78. Bibcode:2022BEcoS..76...78M. doi:10.1007/s00265-022-03185-7. ISSN 1432-0762.

- ^ Burnie, David; Don E. Wilson (2001). Animal. New York, New York: DK Publishing, Inc. pp. 99–101. ISBN 0-7894-7764-5.

- ^ Jaremovic, Renata V.; Croft, David B. (1987). "Comparison of Techniques to Determine Eastern Grey Kangaroo Home Range". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 51 (4): 921–930. doi:10.2307/3801761. ISSN 0022-541X. JSTOR 3801761.

- ^ "Kangaroo culling begins at Australian site". NBC News. 19 May 2008.

- ^ "Kangaroo cull targets millions". BBC News. 21 February 2002.

- ^ "Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment".

- ^ "Kangaroo Culling on Defence lands – Fact Sheet" (PDF). tams.act.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Kangaroo culling begins at Australian site". NBC News. 19 May 2008.

- ^ "Kangaroo cull targets millions". BBC News. 21 February 2002.

- ^ Green-Barber, Jai M.; Old, Julie M. (2018). "Town roo, country roo: A comparison of behaviour in eastern grey kangaroos Macropus giganteus in developed and natural landscapes". Australian Zoologist. 39 (3): 520–533. doi:10.7882/AZ.2018.019.

- ^ Poole, W.E. (1983). "Eastern Grey Kangaroo, Macropus giganteus". In Strahan, R. (ed.). The Australian Museum 'Complete Book of Australian Mammals'. Photographic Index of Australian Wildlife. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. pp. 244–247. hdl:102.100.100/285010.

- ^ Edwards, G. (1989). "The interaction between macropodids and sheep: a review". In Grigg, G.; Jarman, P; Hume, I. (eds.). Kangaroos, wallabies and rat-kangaroos Volume 2. Sydney: Surrey Beatty and Sons. pp. 795–804.

- ^ "Eastern Grey Kangaroo – Australian Museum". australianmuseum.net.au. Retrieved 9 October 2018.