The Promise Ring was an American rock band from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, that is recognized as part of the second wave of emo. Among various other EPs and singles, the band released four studio albums during their initial run: 30° Everywhere (1996), Nothing Feels Good (1997), Very Emergency (1999), and Wood/Water (2002). Their first two albums solidified their place among the emo scene; their third effort shifted toward pop music, while their final record was much more experimental in nature. The band initially broke up in 2002 and has reunited sporadically since then to perform live, but no new material from the band has since been released. They were last active for a live performance in 2016.

The Promise Ring | |

|---|---|

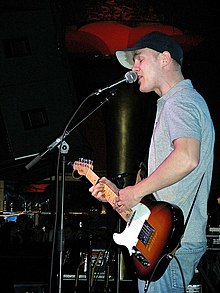

Frontman Davey von Bohlen in 2007 | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Discography | The Promise Ring discography |

| Years active |

|

| Labels | |

| Members |

|

| Past members |

|

The Promise Ring was formed in 1995 by guitarist Jason Gnewikow and drummer Dan Didier. Cap'n Jazz guitarist Davey von Bohlen joined the band soon thereafter and became the band's vocalist. The trio remained the Promise Ring's core members throughout its history. The band has employed a host of other bass guitarists throughout its existence, but their last bassist Scott Schoenbeck has remained with the group the longest. The Promise Ring have had a significant impact on emo music, influencing numerous bands such as Dashboard Confessional, Basement, Title Fight, and Pet Symmetry.[1][2][3][4]

History

editFormation (1995)

editThe Promise Ring was formed in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, from the aftermath of two groups in February 1995: guitarists Jason Gnewikow and Matt Mangan (both from None Left Standing), and drummer Dan Didier and bassist Scott Beschta (both from Ceilishrine).[5] Mangan moved to Indianapolis soon after the group formed,[6] prompting the band to invite Cap'n Jazz guitarist Davey von Bohlen as Mangan's replacement.[7] Bohlen was friends with Gnewikow prior to this, but Didier and Beschta became new acquaintances to him after joining the group.[6] The band recorded a three-track demo which included "Jupiter", "12 Sweaters Red" and "Mineral Point" that March,[8] and played their first show shortly afterward.[9] In June, the group went on a 10-day tour of the East Coast; Bohlen soon returned to tour with Cap'n Jazz to support the release of their debut, Shmap'n Shmazz. After the ninth day of that tour, Cap'n Jazz broke up,[6] and Bohlen was able to focus his time on the Promise Ring.[5]

Early releases and 30° Everywhere (1996–1997)

editThe Promise Ring released a 7-inch vinyl single through Foresight Records, which contained the tracks "Watertown Plank" and "Mineral Point".[5] Foresight was owned by a friend of theirs.[10] The band then went on tour, performing in church halls and basements across the US.[10] Texas Is the Reason guitarist Norman Brannon acquired copies of the group's demo and 7-inch single and gave them to Jade Tree co-founder Tim Own.[6] Shortly afterwards, the band was signed to the independent label for a three-album contract.[11] After further touring at the start of 1996,[10] the Falsetto Keeps Time EP was released in February,[12] and was followed by a split single with Texas Is the Reason in May.[13] Both releases were successful, with the band continuing to tour and work on material that would feature on their debut album.[10]

The Promise Ring's first studio album titled 30° Everywhere, was released by Jade Tree in September 1996.[14] Retrospectively, band members have voiced their dislike of the record; according to Bohlen, the album was recorded in only five days. The band additionally was confused about how they wanted to approach the music on the new record; Bohlen described the situation as one "where we had no idea what we wanted to do or how we wanted it to come out."[6] Didier later spoke of his dislike of Casey Rice's engineering on the record, as well as Bohlen's illness during the recording: "it was the wrong recording at the wrong time with the wrong person."[6]

Despite this, the release was an underground success, earning the group's attention from independent publications.[5] The attention was drawn and aided by the inclusion of "A Picture Postcard", which had earlier appeared on Falsetto Keeps Time and would go on to become a staple of the emo genre.[15] The song again appeared as part of an EP titled The Horse Latitudes, which effectively reissued the band's earlier work in early 1997.[5] Although the band had 500–600 copies of 30° Everywhere to sell over the course of several gigs, the album sold out at CBGB's.[6] The band further promoted 30° Everywhere starting with a six-week US tour with Texas Is the Reason,[10] followed by a European tour in April–May 1997.[10]

Nothing Feels Good (1997–1998)

editImmediately following the European tour's conclusion, the band began writing new material for their second album,[10] sometimes jamming for inspiration.[11] The group went to Memphis, Tennessee, and recorded the album, titled Nothing Feels Good, at Easley McCain Recording with producer J. Robbins of Jawbox.[10] The relationship between Didier and Beschta throughout the sessions progressively deteriorated.[6] Around the release of Nothing Feels Good,[16] For the album's supporting tour, Beschta was replaced on bass by Tim Burton, a former bandmate of Gnewikow's in None Left Standing. [5] A music video was made for the album's fourth track, "Why Did Ever We Meet"; it was directed by Darren Doane.[9] Though the sessions were marked by turbulence, the album received excellent critical reception,[17][18][19][20] and was featured on best-of album lists for the year by The New York Times and Teen People.[10]

In February 1998, the band was traveling back home from a show[21] while on tour with Hum[6] during a snowstorm.[5] While driving through Nebraska, their van flipped over after Bohlen hit a bump on the road;[21] Bohlen flew head-first through the windshield. Bohlen (who had head trauma), Burton (who had broken bones),[15] and Didier were released from the hospital the following morning. Gnewikow, however, was in the intensive care unit for three further weeks due to a broken collarbone and other injuries.[21] Following the van accident, the band decided to replace their bassist once again, hiring Scott Schoenbeck in favor of Burton.[5] The band took a six-week break to recover from the van accident before resuming shows with Jimmy Eat World in the East Coast of the US,[6] and a European stint with Jets to Brazil. The band again toured with Jets to Brazil across the US in October and Japan in November.[22]

Boys + Girls, Very Emergency and Electric Pink (1998–2001)

editIn October 1998, the band released the Boys + Girls EP, which contained the two tracks "Tell Everyone We're Dead" and "Best Looking Boys".[23] In March 1999, the band performed new material during a few shows, leading up to their European tour that April. Following that stint, the group began recording their next album Very Emergency, at Inner Ear Studios in Washington, D.C.[24] J. Robbins would return as the producer of the new album, but production credit was this time split between Robbins and the band.[25] Robbins, Jenny Toomey and Smart Went Crazy member Hilary Soldati made guest appearances on the album. The recordings were mixed at Smart Studios, before they were mastered by Alan Douches at West Side Music.[25]

Jade Tree released Very Emergency on September 28, 1999.[26] Around the time of release, they went on a brief tour to promote the album on the East Coast and in Canada with Euphone.[27] Doane returned to film the music video for "Emergency! Emergency!";[9] the band agreed to make the video because Doane volunteered to do it for free.[28] It premiered on 120 Minutes in October.[29] The band reconvened with Robbins to tour the US with his band, Burning Airlines, through October and November;[10] they were joined by Pele and the Dismemberment Plan, among others. Further shows were added with Burning Airlines, pushing the trek into early December.[30] The band performed in Japan in February 2000,[31] before taking a break. They went on an American East Coast and Midwest tour the following month[32] with Rich Creamy Paint, the Explosion and Pele.[33]

In May and June, the band was scheduled to go on a European tour with Burning Airlines,[34] however, on the day they were due to leave to begin the shows,[35] Bohlen was diagnosed with meningioma, a brain tumor variant. The tour was immediately cancelled[36] and Bohlen underwent surgery on May 8.[37] Up to this point, he had been suffering from strong headaches whenever the band performed for a year and a half.[35] Two outtakes from the Very Emergency sessions were included on the Electric Pink EP, released in mid-May.[38] The band took the next few months off to recuperate.[39] They began playing shows again in September, when the band supported Bad Religion[40] for three weeks on their US tour;[35] however, Bohlen developed a post-operative infection during this stint that resulted in the group dropping off.[36] They played shows in February 2001 to make up for the cancelled shows they had planned for December.[41]

New record label, Wood/Water and disbandment (2001–2002)

editAfter finishing the rescheduled tour dates in February, the Promise Ring went and worked on material with Kristian Riley of Citizen King.[42] By March 2001, the band had parted ways with Jade Tree, as the label was unable to give the amount of financial support that the band was looking for.[43] After being courted by Epitaph Records,[44][45] the group signed with their imprint Anti- later that year.[35][46] With Anti-, the group were also looking to move further away from emo, which the band had become increasingly known for while on Jade Tree. Bohlen would liken his band and the label to each other as stylistically synonymous.[47][48] The group also experienced licensing conflicts with Jade Tree, resulting in difficulties distributing the Promise Ring's releases to labels in other countries, including European releases of Electric Pink and album releases in Japan.[11]

Coinciding with an April and May 2001 tour with Camden, their frontman William Seidel was welcomed to the Promise Ring as their touring keyboardist.[49][50][51] With Didier, Bohlen, and Gnewikow being fans of the Smiths and Blur, the band chose Stephen Street to produce their fourth album, as he had produced for both of those groups.[52] The band ran into budget issues after Street went on vacation and were unable to contact him,[53] so they instead decided to split the recording between Street in the London and Mario Caldato Jr. in Los Angeles. "Say Goodbye Good" was produced by Caldato during this period, but the majority of the record ended up being produced by Street at Jacobs Studios in Farnham.[54][55] Schoenbeck was unhappy with the stylistic change during the Los Angeles sessions and left before working with Street.[45][52] He was replaced by Ryan Weber of Camden for the remainder of the album's recording.[56][57]

The title, Wood/Water, was announced in December 2001; it would be released on April 23, 2002.[58] It was preceded by an online release of "Get on the Floor" in March,[59] as well as an appearance at South by Southwest later that month.[36] During this performance, Bohlen fainted; he had additional surgery over the next few weeks involving a plate being implanted in his head.[60] Wood/Water was made available for streaming in its entirety on March 26, 2002, via a microsite before its April 23 release.[61][62][63] The album spawned a single and music video for "Stop Playing Guitar". The video was posted online on May 3, and it was directed by former GusGus members Arni + Kinski.[64][65] The song was also released as a single on July 9 on 7" vinyl and CD.[66][67][68]

To promote the album, the Promise Ring began by delivering two acoustic in-store performances, and then headlined a US tour in April and May 2002, being supported by the Weakerthans.[69] On May 24, 2002, the band performed on Late Night with Conan O'Brien,[70] then moved on to a supporting slot on Jimmy Eat World's tour of the UK. Wood/Water was released in the UK during this stint on May 27, 2002.[71][72] The Promise Ring's supporting slot for Jimmy Eat World continued into some US dates in late July and early August 2002.[72] In September and October, the band made what would be their final appearances as part of the 2002 Plea for Peace tour.[73]

Although the Promise Ring planned to film a video for "Suffer Never" after Plea for Peace,[45] Epitaph and Anti- announced on October 14, 2002, that they had broken up.[74] The band explained the following week that they had decided to focus on other projects, and had been considering parting ways for several months.[75]

Related acts and reunions

editThe first side project originating from the Promise Ring began in 1999, when Bohlen and Didier formed the acoustic side project Vermont, which featured Chris Rosenau of Pele.[76] Seidel and Weber formed Decibully in 2001, with Gnewikow joining them briefly as their drummer.[77] In late 2000, Bohlen was a guest on "A Praise Chorus" by Jimmy Eat World, who the Promise Ring had befriended on tour;[78] the song became a promotional single for its parent album, Bleed American, in 2002.[79] In 2003, Bohlen and Didier formed In English with Eric Axelson, formerly of the Dismemberment Plan; the group would later become known as Maritime.[80] They released their debut studio album Glass Floor in 2004 through DeSoto Records after it had been passed on by Anti-,[80][81] and have since released four more studio albums.

The Promise Ring has reunited for several reunion shows and tours. These began with a one-off show at the Flower 15 Festival in late November 2005 at Metro Chicago.[82] Following a tweet in November 2011,[83] the band played two reunion shows in February 2012.[84] To coincide with the reunion, the Promise Ring announced they would be releasing a rarities collection in the summer of 2012 on former (and reunited) manager Jeff Castelaz's record label, Dangerbird Records;[85] this collection never surfaced. Between May and September 2012, the band played a variety of US shows and festivals, including The Bamboozle, Riot Fest, and Fun Fun Fun Fest.[86][87][88] Around the time of the latter performance, Didier said they had "no interest at all to write new music" and that they had "no plan whatsoever" to play together again.[88] On New Year's Eve 2015, the band played Nothing Feels Good in its entirety at a one-off show at Metro Chicago; when asked about more material, Didier said: "Maybe more shows, but definitely not new music".[89] They then appeared at the 2016 Wrecking Ball festival.[90]

Musical style

editThe Promise Ring's style has been described at various points throughout their career as emo,[5][91] indie rock,[5][91] pop-punk,[91] power pop,[92][93][94] and indie pop.[95] The group began as a continuation of the founding members' previous bands: emo bands None Left Standing, Ceilishrine, and Cap'n Jazz, all of whom played a particular kind of emo localized in the Midwestern United States.[5] The Promise Ring became known as part of "second wave" emo,[96] which was more geographically diverse than the first; Theo Cateforis wrote in Grove Music Online that the Promise Ring became leaders of this period alongside Austin, Texas-based Mineral and Seattle, Washington-based Sunny Day Real Estate.[97] Over the duration of their original run, the Promise Ring would progressively distance themselves from the genre, moving towards pop between Nothing Feels Good[15] and Very Emergency[98][99][100] and starting from scratch on Wood/Water with their new label.[47][48]

Their debut record 30° Everywhere carried post-hardcore and punk rock influences,[6][15] and has been praised as a benchmark and blueprint for emo as a whole.[44] Though the band reportedly did not like the album in retrospect,[6][101] it was praised for its "very catchy, very intense, [and] very powerful" material.[102] The group opted for a cleaner, more pop-oriented sound on Nothing Feels Good, which contrasted 30° Everywhere and the punk-like approach Bohlen used in Cap'n Jazz,[15] with critics noting a shift toward power pop[15][19][103] in addition to the band's already established emo sound.[104][105][106] Nothing Feels Good is noted for pushing the band to the forefront of the emo scene,[28] which helped to forge the way for subsequent landmark releases by their peers, such as Something to Write Home About (1999) by the Get Up Kids and Bleed American (2001) by Jimmy Eat World.[105]

Nothing Feels Good and the Boys + Girls EP foreshadowed the Promise Ring completely shifting toward pop,[107] which was fully displayed on Very Emergency.[98][99][100] The sessions with Riley sparked another stylistic turn, differing significantly from that of Very Emergency;[55][49] Wood/Water, the only full-length to follow the band's releases on Jade Tree, was an alternative country,[56][108] indie rock,[109][110] and pop album,[111] with elements of roots rock, alternative pop,[17] and psychedelic pop.[52]

Members

edit|

Most recent lineup

|

Past members

Touring members

|

Timeline

edit

Discography

editStudio albums

- 30° Everywhere (1996)

- Nothing Feels Good (1997)

- Very Emergency (1999)

- Wood/Water (2002)

References

editCitations

- ^ Stanton, Leanne Aciz (January 18, 2017). "An Interview With Dashboard Confessional: Their Hearts.Beat.HERE". The Aquarian Weekly. Archived from the original on October 3, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ Reid, Sean (July 19, 2010). "INTERVIEW: BASEMENT". Alter the Press. Archived from the original on December 9, 2023. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

90's Emo bands like Promise Ring, Mineral, Braid are a few that we are influenced by, and recently I have been playing a lot of Smoking Popes and Jets to Brazil, which are having a strong impact on our newer material.

- ^ "Title Fight". The Music. October 19, 2009. Archived from the original on November 16, 2023. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ Anderl, Tim (July 13, 2015). "INTERVIEW: PET SYMMETRY TALK ABOUT PIZZA & ACTOR EDDIE FURLONG". New Noise Magazine. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Huey, Steve. "The Promise Ring | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on March 26, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Galil, Leor (February 24, 2012). "An oral history of The Promise Ring". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "Cap'n Jazz | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ The Promise Ring (1995). The Promise Ring (sleeve). Self-released.

- ^ a b c "FAQ". The Promise Ring. Archived from the original on October 18, 2000. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The Promise Ring". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on February 20, 1999. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c Hiller, Joachim (September–November 2000). "Promise Ring". Ox-Fanzine (in German). Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ "Falsetto Keeps Time - The Promise Ring". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "The Promise Ring/Texas Is the Reason - The Promise Ring / Texas Is the Reason". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "30° Everywhere - The Promise Ring". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Cepeda, Eduardo (August 31, 2017). "The Promise Ring's 'Nothing Feels Good' Proved There Was Room for Pop in Emo". Vice. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ "Nothing Feels Good - The Promise Ring". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ a b Butler, Blake. "Nothing Feels Good – The Promise Ring". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Hiller, Joachim (1997). "Promise Ring Nothing feels good CD". Ox-Fanzine (in German). Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Mirov, Nick (December 1997). "Promise Ring: Nothing Feels Good". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 19, 2003. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Pelone, Joe (December 9, 2011). "The Promise Ring - Nothing Feels Good". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2018. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c Salamon 1999, p. 148

- ^ "News". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on February 21, 1999. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ "Boys + Girl - The Promise Ring". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ "News". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on April 20, 1999. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b The Promise Ring (1999). Very Emergency (booklet). Jade Tree. JT1043/7 92258 1043 2 5.

- ^ Butler, Blake. "Very Emergency - The Promise Ring | Release Info". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "News". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on October 6, 1999. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Jacks 1999, p. 68

- ^ "News". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on November 4, 1999. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ "Tours". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on November 4, 1999. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "Tours". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on February 29, 2000. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "News". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on February 29, 2000. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ "Tours". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on March 10, 2000. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "Tours". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on May 10, 2000. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Green, Stuart (February 1, 2000). "Promise Ring The Difference A Year Makes". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c Heller, Greg (February 12, 2002). "Promise Ring Knock Off "Wood"". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 7, 2002. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Rock Beat: Santana, AC/DC, Promise Ring ..." MTV. May 12, 2000. Archived from the original on March 18, 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ "News". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on May 10, 2000. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ "News". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ "The Promise Ring". The Promise Ring. Archived from the original on February 12, 2005. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Tanzilo, Bobby (January 23, 2001). "The Promise Ring hits the road". OnMilwaukee. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Tarlach, Gemma (April 22, 2002). "From Promise Rings' trials emerges gem of a record". Anti-. Archived from the original on December 25, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Gironi, Carlo (April 8, 2002). "An Interview With The Promise Ring". Anti-. Archived from the original on December 25, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Heller, Jason (April 25, 2002). "Promise Keepers". Westword. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c Heisel, Scott (August 28, 2002). "The Promise Ring". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Wargo, Nanette (September 28, 2001). "Promise Ring Records New LP for Anti". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Crane, Zac (May 9, 2002). "What To Do? On its latest, The Promise Ring changes everything except its name". Anti-. Archived from the original on December 25, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Hiller, Joachim (March–May 2002). "Promise Ring". Ox-Fanzine (in German). Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Downs, Gordon (May 15, 2002). "A Whole New Promise". Anti-. Archived from the original on December 30, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ "Tours". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on April 9, 2001. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "Bio". Decibully. Archived from the original on December 17, 2003. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Stewart, Barb (April 26, 2002). "The Promise Ring Suffer Nevermore". Anti-. Archived from the original on December 25, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Menocal, Peter (October 2002). "Interview: The Promise Ring". Kludge. Archived from the original on December 16, 2002. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "The Promise Ring". Anti-. Archived from the original on February 14, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ a b The Promise Ring (2002). Wood/Water (booklet). Anti-. 6617-2.

- ^ a b Herboth, Eric J. "The Promise Ring - Wood/Water". LAS Magazine. Archived from the original on December 13, 2005. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Tours". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on April 9, 2001. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "The Promise Ring announce the official release date for their upcoming album". Anti-. February 6, 2002. Archived from the original on February 6, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (March 3, 2002). "New Promise Ring MP3 on Anti.com". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Abbott, Spencer H. (May 7, 2002). "Eye of the Tiger". Anti-. Archived from the original on December 25, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ White, Adam (March 26, 2002). "Hear the entire new Promise Ring record". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "The Promise Ring's 'Wood/Water' is out! Hear it in full on the TPR 'Microsite' and download a new MP3!". Anti-. April 23, 2002. Archived from the original on June 3, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ White, Adam (January 14, 2002). "Promise Ring to release Woodwater on April 23". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "The new Promise Ring video for 'Stop Playing Guitar' is now up!". Anti-. May 3, 2002. Archived from the original on June 3, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ "The Promise Ring shoot video for 'Stop Playing Guitar'". The Promise Ring. Archived from the original on October 31, 2003. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "Stop Playing Guitar - The Promise Ring". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ The Promise Ring (2002). "Stop Playing Guitar" (sleeve). Anti-. 1068-7.

- ^ The Promise Ring (2002). "Stop Playing Guitar" (sleeve). Anti-. 1068-2.

- ^ White, Adam (March 18, 2002). "Massive Promise Ring Update". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Heisel, Scott (April 7, 2002). "Promise Ring to appear on Conan O'Brien". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Begrand, Adrien (May 31, 2002). "The Promise Ring Wood/Water". PopMatters. Archived from the original on June 7, 2002. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Heisel, Scott (May 12, 2002). "Jimmy continues in never-ending quest to Eat World". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ White, Adam (July 22, 2002). "Plea For Peace / Take Action dates with bands!". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on August 25, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "Daily News". Kludge. Archived from the original on March 5, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Alvarez, Ted (October 22, 2002). "Promise Ring Split". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 30, 2002. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Vermont | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 17, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Mass, Tyler (April 10, 2014). "Decibully talks history, break-up, Milwaukee Day reunion". Milwaukee Record. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Wallace, Brian (July 26, 2001). "Pop Goes Emo on Jimmy Eat World's Bleed American". MTV. Archived from the original on May 19, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ^ Jimmy Eat World (2002). "A Praise Chorus" (sleeve). DreamWorks Records. DRMR-14007-2.

- ^ a b Wood, Mikael (July 16, 2004). "Emo-plus". The Boston Phoenix. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ McMahan, Tim (June 8, 2004). "Maritime: No More Promises". Lazy-I. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022 – via Tim McMahan.

- ^ Tanzilo, Bobby (February 15, 2012). "Is The Promise Ring back for good?". OnMilwaukee. Archived from the original on July 22, 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Aubin (November 18, 2011). "Are the Promise Ring back together?". Punknews.org. Archived from the original on November 22, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Yancey, Bryne (November 22, 2011). "Exclusive: The Promise Ring announce Milwaukee and Chicago shows, plan rarities album". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ "The Promise Ring Reunite for Two Shows & Rarities Album in 2012 « Dangerbird Records". Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ Yancey, Bryne (April 30, 2012). "The Promise Ring announce summer tour dates, including Bamboozle". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Roffman, Michael (May 15, 2012). "Elvis Costello, Iggy and the Stooges, and The Jesus and Mary Chain head Riot Fest 2012". Consequence. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Solomon, Dan (November 7, 2012). "The Promise Ring Reunion Comes to a Close". MTV Hive. Archived from the original on November 15, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Payne, Chris (December 31, 2015). "The Promise Ring Talks Rare New Year's Eve Reunion Show, What Future Holds". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ "The Promise Ring + Milemarker at Wrecking Ball 2016". Jade Tree. March 22, 2016. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hyden, Steven (February 25, 2012). "The Promise Ring Reunite at Milwaukee's Turner Hall". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "Promise Ring Poppier On 'Woodwater'". Billboard. April 19, 2002. Archived from the original on September 20, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Promise Ring". Jade Tree. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ Dookey, Spence (May 2–8, 2002). "Metroactive Music | The Promise Ring". Metroactive. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ D'Angelo, Peter J. "The Promise Ring - Horse Latitudes". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Sims, Josh (2014). 100 Ideas that Changed Street Style. London: Laurence King.

- ^ Cateforis, Theo (July 25, 2013). "Emo". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2240803.

- ^ a b Mirov, Nick (November 1, 1999). "Promise Ring: Very Emergency". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Raftery, Brian M. (November 12, 1999). "Very Emergency". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Kandell, Steve (December 8, 1999). "Polished Power Pop". MTV. Archived from the original on February 15, 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ King, Ian (October 4, 2019). "Emo at the Crossroads: 'Very Emergency' and 'Something to Write Home About' at 20". Under the Radar. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ Butler, Blake. "30° Everywhere – The Promise Ring". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Dookey, Spence (May 3, 2002). "Float On". Anti-. Archived from the original on December 25, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Eakin, Marah (November 21, 2015). "An app for lists, live Rush, and 3 old Promise Ring favorites". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Damante, Mike (January 14, 2016). "Essential album: The Promise Ring-'Nothing Feels Good'". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Blest, Paul (June 18, 2014). "Jade Tree: The Essentials, the Overlooked, and the Rightfully Forgotten". Vice. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Butler, Blake. "Very Emergency - The Promise Ring". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ D'Angelo 2002, p. 5

- ^ Finnell, Scott (April 18, 2002). "The Promise Ring 'Wood/Water'". Anti-. Archived from the original on December 25, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Mohager, Kamruz (March 27, 2002). "The Promise Ring 'Wood/Water'". Anti-. Archived from the original on December 25, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ Citations regarding publications calling the album pop:

- D'Angelo 2002, p. 5

- Murray, Noel (May 21, 2002). "The Promise Ring: Wood/Water". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Ahmed, Imran (September 12, 2005). "Promise Ring : Wood/Water". NME. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Wigger, Ian (2002). "The most important CDs of the week". Der Spiegel (in German). Archived from the original on June 6, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Hiller, Joachim (March–May 2002). "Promise Ring". Ox-Fanzine (in German). Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

Sources

- D'Angelo, Peter (April 22, 2002). "The Week's Best New Music". CMJ New Music Report. Vol. 71, no. 759. ISSN 0890-0795.

- Jacks, Kelso (October 18, 1999). "In the Event of a Very Emergency..." CMJ New Music Report. 60 (639). ISSN 0890-0795. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Salamon, Jeff (November 1999). "Emotional Rescue". Spin. 15 (11). ISSN 0886-3032. Archived from the original on August 2, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

External links

edit- The Promise Ring at Facebook

- The Promise Ring discography at Discogs

- The Promise Ring artist page at Jade Tree