Emile, or On Education (French: Émile, ou De l’éducation) is a treatise on the nature of education and on the nature of man written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who considered it to be the "best and most important" of all his writings.[1] Due to a section of the book entitled "Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar", Emile was banned in Paris and Geneva and was publicly burned in 1762, the year of its first publication.[2] It was forbidden by the Church being listed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.[a] During the French Revolution, Emile served as the inspiration for what became a new national system of education.[3] After the American Revolution, Noah Webster used content from Emile in his best-selling schoolbooks and he also used it to argue for the civic necessity of broad-based female education.[4]

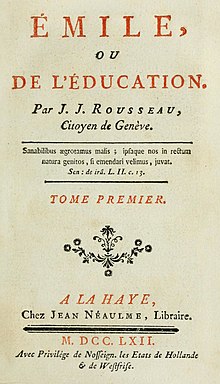

Title page of Rousseau's Emile | |

| Author | Jean-Jacques Rousseau |

|---|---|

| Language | French |

| Subject | Pedagogy |

Publication date | 1762 |

| Publication place | Republic of Geneva and France |

Published in English | 1763 |

Politics and philosophy

editThe work tackles fundamental political and philosophical questions about the relationship between the individual and society: how, in particular, the individual might retain what Rousseau saw as innate human goodness but remain part of a corrupting collectivity. It has a famous opening sentence: "Everything is good as it leaves the hands of the Author of things; everything degenerates in the hands of man".

Rousseau seeks to describe a system of education that would enable the natural man he identifies in The Social Contract (1762) to survive corrupt society.[5] He employs the novelistic device of Emile and his tutor to illustrate how such an ideal citizen might be educated. Emile is scarcely a detailed parenting guide but contains some specific advice on raising children.[6] It is regarded by some as the first philosophy of education in Western culture to have a serious claim to completeness and as one of the first Bildungsroman novels.[7]

Book divisions

editThe text is divided into five books: the first three are dedicated to the child Emile, the fourth to an exploration of the adolescent, and the fifth to outlining the education of his female counterpart Sophie, as well as to Emile's domestic and civic life.

Book I

editIn Book I, Rousseau discusses not only his fundamental philosophy but also begins to outline how one would have to raise a child to conform with that philosophy. He begins with the early physical and emotional development of the infant and the child.

Emile attempts to "find a way of resolving the contradictions between the natural man who is 'all for himself' and the implications of life in society".[8] The famous opening line does not bode well for the educational project—"Everything is good as it leaves the hands of the Author of things; everything degenerates in the hands of man".[9] But Rousseau acknowledges that every society "must choose between making a man or a citizen"[10] and that the best "social institutions are those that best know how to denature man, to take his absolute existence from him in order to give him a relative one and transport the I into the common unity".[11] To "denature man" for Rousseau is to suppress some of the "natural" instincts that he extols in The Social Contract, published the same year as Emile, but while it might seem that for Rousseau such a process would be entirely negative, this is not so. Emile does not lament the loss of the noble savage. Instead, it is an effort to explain how natural man can live within society.

Many of Rousseau's suggestions in this book are restatements of the ideas of other educational reformers. For example, he endorses Locke's program of "harden[ing children's] bodies against the intemperance of season, climates, elements; against hunger, thirst, fatigue".[12] He also emphasizes the perils of swaddling and the benefits of mothers nursing their own infants. Rousseau's enthusiasm for breastfeeding led him to argue: "[B]ut let mothers deign to nurse their children, morals will reform themselves, nature's sentiments will be awakened in every heart, the state will be repeopled"[13]—a hyperbole that demonstrates Rousseau's commitment to grandiose rhetoric. As Peter Jimack, the noted Rousseau scholar, argues: "Rousseau consciously sought to find the striking, lapidary phrase which would compel the attention of his readers and move their hearts, even when it meant, as it often did, an exaggeration of his thought". And, in fact, Rousseau's pronouncements, although not original, affected a revolution in swaddling and breastfeeding.[14]

Book II

editThe second book concerns the initial interactions of the child with the world. Rousseau believed that at this phase the education of children should be derived less from books and more from the child's interactions with the world, with an emphasis on developing the senses, and the ability to draw inferences from them. Rousseau concludes the chapter with an example of a boy who has been successfully educated through this phase. The father takes the boy out flying kites, and asks the child to infer the position of the kite by looking only at the shadow. This is a task that the child has never specifically been taught, but through inference and understanding of the physical world, the child is able to succeed in his task. In some ways, this approach is the precursor of the Montessori method.

Book III

editThe third book concerns the selection of a trade. Rousseau believed it necessary that the child must be taught a manual skill appropriate to his sex and age, and suitable to his inclinations, by worthy role models.[15]

Book IV

editOnce Emile is physically strong and learns to carefully observe the world around him, he is ready for the last part of his education—sentiment: "We have made an active and thinking being. It remains for us, in order to complete the man, only to make a loving and feeling being—that is to say, to perfect reason by sentiment".[17] Emile is a teenager at this point and it is only now that Rousseau believes he is capable of understanding complex human emotions, particularly sympathy. Rousseau argues that, while a child cannot put himself in the place of others, once he reaches adolescence and becomes able to do so, Emile can finally be brought into the world and socialized.[18]

In addition to introducing a newly passionate Emile to society during his adolescent years, the tutor also introduces him to religion. According to Rousseau, children cannot understand abstract concepts such as the soul before the age of about fifteen or sixteen, so to introduce religion to them is dangerous. He writes: "It is a lesser evil to be unaware of the divinity than to offend it".[19] Moreover, because children are incapable of understanding the difficult concepts that are part of religion, he points out that children will only recite what is told to them—they are unable to believe.

Book IV also contains the famous "Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar", the section that was largely responsible for the condemnation of Emile and the one most frequently excerpted and published independently of its parent tome. Rousseau writes at the end of the "Profession": "I have transcribed this writing not as a rule for the sentiments that one ought to follow in religious matters, but as an example of the way one can reason with one's pupil in order not to diverge from the method I have tried to establish".[20] Rousseau, through the priest, leads his readers through an argument which concludes only to belief in "natural religion": "If he must have another religion", Rousseau writes (that is, beyond a basic "natural religion"), "I no longer have the right to be his guide in that".[21]

Book V

editIn Book V, Rousseau turns to the education of Sophie, Emile's wife-to-be.

Rousseau begins his description of Sophie, the ideal woman, by describing the inherent differences between men and women in a famous passage:

In what they have in common, they are equal. Where they differ, they are not comparable. A perfect woman and a perfect man ought not to resemble each other in mind any more than in looks, and perfection is not susceptible of more or less. In the union of the sexes each contributes equally to the common aim, but not in the same way. From this diversity arises the first assignable difference in the moral relations of the two sexes.

For Rousseau, "everything man and woman have in common belongs to the species, and ... everything which distinguishes them belongs to the sex".[22] Rousseau states that women should be "passive and weak", "put up little resistance" and are "made specially to please man"; he adds, however, that "man ought to please her in turn", and he explains the dominance of man as a function of "the sole fact of his strength", that is, as a strictly "natural" law, prior to the introduction of "the law of love".[22]

Rousseau's stance on female education, much like the other ideas explored in Emile, "crystallize existing feelings" of the time. During the eighteenth century, women's education was traditionally focused on domestic skills—including sewing, housekeeping, and cooking—as they were encouraged to stay within their suitable spheres, which Rousseau advocates.[23]

Rousseau's brief description of female education sparked an immense contemporary response, perhaps even more so than Emile itself. Mary Wollstonecraft, for example, dedicated a substantial portion of her chapter "Animadversions on Some of the Writers who have Rendered Women Objects of Pity, Bordering on Contempt" in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) to attacking Rousseau and his arguments.

When responding to Rousseau's argument in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft directly quotes Emile in Chapter IV of her piece:

"Educate women like men," says Rousseau [in Emile], "and the more they resemble our sex the less power will they have over us." This is the very point I aim at. I do not wish them to have power over men; but over themselves.[24]

French writer Louise d'Épinay's Conversations d'Emilie made her disagreement with Rousseau's take on female education clear as well. She believes that females' education affects their role in society, not natural differences as Rousseau argues.[25]

Rousseau also touches on the political upbringing of Emile in book V by including a concise version of his Social Contract in the book. His political treatise The Social Contract was published in the same year as Emile and was likewise soon banned by the government for its controversial theories on general will. The version of this work in Emile, however, does not go into detail concerning the tension between the Sovereign and the Executive, but instead refer the reader to the original work.[26]

Émile et Sophie

editIn the incomplete sequel to Emile, Émile et Sophie (English: Emilius and Sophia), published after Rousseau's death, Sophie is unfaithful (in what is hinted at might be a drugged rape), and Emile, initially furious with her betrayal, remarks "the adulteries of the women of the world are not more than gallantries; but Sophia an adulteress is the most odious of all monsters; the distance between what she was, and what she is, is immense. No! there is no disgrace, no crime equal to hers".[27] He later relents somewhat, blaming himself for taking her to a city full of temptation, but he still abandons her and their children. Throughout the agonized internal monologue, represented through letters to his old tutor, he repeatedly comments on all of the affective ties that he has formed in his domestic life—"the chains [his heart] forged for itself".[28] As he begins to recover from the shock, the reader is led to believe that these "chains" are not worth the price of possible pain—"By renouncing my attachments to a single spot, I extended them to the whole earth, and, while I ceased to be a citizen, became truly a man".[29] While in La Nouvelle Héloïse the ideal is domestic, rural happiness (if not bliss), in Emile and its sequel the ideal is "emotional self-sufficiency which was the natural state of primitive, pre-social man, but which for modern man can be attained only by the suppression of his natural inclinations".[30] According to Dr. Wilson Paiva, member of the Rousseau Association, "[L]eft unfinished, Émile et Sophie reminds us of Rousseau's incomparable talent for producing a brilliant conjugation of literature and philosophy, as well as a productive approach of sentiment and reason through education".[31]

Reviews

editRousseau's contemporary and philosophical rival Voltaire was critical of Emile as a whole, but admired the section in the book which had led to it being banned (the section titled "Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar"). According to Voltaire, Emile is

a hodgepodge of a silly wet nurse in four volumes, with forty pages against Christianity, among the boldest ever known...He says as many hurtful things against the philosophers as against Jesus Christ, but the philosophers will be more indulgent than the priests.

However, Voltaire went on to endorse the Profession of Faith section and called it "fifty good pages... it is regrettable that they should have been written by... such a knave".[32]

The German scholar Goethe wrote in 1787 that "Emile and its sentiments had a universal influence on the cultivated mind".[33]

See also

edit- Original Stories from Real Life, a response text written by Mary Wollstonecraft

- Robinson Crusoe

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Confessions. Trans. J.M. Cohen. New York: Penguin (1953), 529-30.

- ^ E. Montin, "Introduction to J. Rousseau's Émile: or, Treatise on education by Jean-Jacques Rousseau", William Harold Payne, transl. (D. Appleton & Co., 1908) p. 316.

- ^ Jean Bloch traces the reception of Emile in France, particularly amongst the revolutionaries, in his book Rousseauism and Education in Eighteenth-century France Oxford: Voltaire Foundation (1995).

- ^ Harris, Micah (2024-09-01). "Noah Webster and the Influence of Rousseau on Education in America, 1785–1835". American Political Thought. 13 (4): 505–527. doi:10.1086/732277. ISSN 2161-1580.

- ^ William Boyd (1963). The Educational Theory of Jean Jacques Rousseau. Russell. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8462-0359-9.

- ^ Rousseau, responding in frustration to what he perceived as a gross misunderstanding of his text, wrote in Lettres de la montagne: "Il s'sagit d'un nouveau système d'èducation dont j'offre le plan à l'examen des sages, et non pas d'une méthode pour les pères et les mères, à laquelle je n'ai jamais songé". [It is about a new system of education, whose outline I offer up for learned scrutiny, and not a method for fathers and mothers, which I have never contemplated.] Qtd. in Peter Jimack, Rousseau: Émile. London: Grant and Cutler, Ltd. (1983), 47.

- ^ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Emile. Trans. Allan Bloom. New York: Basic Books (1979), 6.

- ^ Jimack, 33.

- ^ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Emile, or On Education. Trans. Allan Bloom. New York: Basic Books (1979), 37.

- ^ Rousseau, 39.

- ^ Roussesau, 40.

- ^ Rousseau, 47.

- ^ Rousseau, 46.

- ^ Jimack, 46-7.

- ^ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (1979). translation and notes by Allan Bloom (ed.). Emile or On Education. New York: Basic Books. pp. 202–207. ISBN 978-0465-01931-1. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Trouille, 16.

- ^ Rousseau, 203.

- ^ Rousseau, 222.

- ^ Rousseau, 259.

- ^ Rousseau, 313.

- ^ Rousseau, 314.

- ^ a b Rousseau, 358.

- ^ Todd, Christopher (1998). "Reviewed work: Rousseau and Education in Eighteenth-Century France, Jean Bloch". The Modern Language Review. 93 (4): 1111–1112. doi:10.2307/3736314. JSTOR 3736314.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, Mary (1792). A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. p. 80. ISBN 9783849681050.

- ^ Hageman, Jeanne Kathryn (1991). Les Conversations d'Emilie: The education of women by women in eighteenth century France. The University of Wisconsin – Madison. p. 28. OCLC 25301342.

- ^ Patrick J. Deneen, The Odyssey of Political Theory, p. 145. Google Books

- ^ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Emilius and Sophia; or, The Solitaries. London: Printed by H. Baldwin. (1783), 31.

- ^ Rousseau, Émile et Sophie, 46.

- ^ Rousseau, Émile et Sophie, 58.

- ^ Jimack, 37.

- ^ Paiva, Wilson. "(Re)visiting Émile after marriage: The importance of an appendix".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Will Durant (1967). The Story of Civilization Volume 10:Rousseau and Revolution. pp. 190–191.

- ^ Will Durant (1967). The Story of Civilization Volume 10:Rousseau and Revolution. p. 889.

33. Paiva, Wilson A. Discussing human connectivity in Rousseau as a pedagogical issue. Educ. Pesqui., São Paulo, v. 45, e191470, 2019. Link: http://educa.fcc.org.br/pdf/ep/v45/en_1517-9702-ep-45-e191470.pdf

Bibliography

edit- Bloch, Jean. Rousseauism and Education in Eighteenth-century France. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1995.

- Boyd, William. The Educational Theory of Jean Jacques Rousseau. New York: Russell & Russell, 1963.

- Jimack, Peter. Rousseau: Émile. London: Grant and Cutler, Ltd., 1983.

- Reese, William J. (Spring 2001). "The Origins of Progressive Education". History of Education Quarterly. 41 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5959.2001.tb00072.x. ISSN 0018-2680. JSTOR 369477. S2CID 143244952.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Emile, or On Education. Trans. Allan Bloom. New York: Basic Books, 1979.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Emilius and Sophia; or, The Solitaries. London: Printed by H. Baldwin, 1783.

- Trouille, Mary Seidman. Sexual Politics in the Enlightenment: Women Writers Read Rousseau. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1997.

External links

edit- The Emile of Jean-Jacques Rousseau at Columbia.edu – complete French text and English translation by Grace G. Roosevelt (an adaptation and revision of the Foxley translation)

- Emile at Project Gutenberg in an English translation by Barbara Foxley

- Rousseau's Émile; or, Treatise on education (abridged English translation by William Harold Wayne; 1892) at Archive.org

- Èmile public domain audiobook at LibriVox