Oliver LaGrone (December 9, 1906 – October 15, 1995) was an African-American sculptor, poet, educator, and humanitarian. In 1974, a post-secondary scholarship was created in his name, enlarged and refocused in 1991 for graduates of the public high school of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

LaGrone's artistic creations focused primarily on honoring African-American capacity and accomplishment. His sculptures can be seen at three campuses of The Pennsylvania State University (Harrisburg, State College, Scranton), The State Museum of Pennsylvania, at the Unitarian Church of Harrisburg, the Schomburg Center of New York City, the Albuquerque Museum, and at Albuquerque's Richardson Pavilion of the New Mexico Hospitals. Other of his sculptures are held privately. His collected poetry is held by the Special Collections Library of The Pennsylvania State University as well as by numerous other academic libraries and private collections.

Family of origin, 1906-1927

editClarence Oliver LaGrone was born December 9, 1906, in McAlester, in Indian Territory, the year before the Territory became part of the new state of Oklahoma. His father, William Lee LaGrone, born ten years after the abolition of slavery in the United States, to formerly enslaved parents,[1] had settled in Indian Territory because of the relative freedoms it afforded. William LaGrone had left Mississippi in 1895, in fear of his life following an altercation with two white men over their attack on William's mother. William had married Lula Evelyn Cochran in Alabama after she and her parents helped him recover from his flight. They migrated to Texas, seeking safety from potential pursuers.[2]

LaGrone's normal school-educated father served on the school board and as an ordained pastor of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church.[3] Education was important to William LaGrone, particularly educating blacks in the importance of their heritage, a legacy that informed his son's life's work.[4] "My father was a gifted writer, and also a builder, and extremely creative," LaGrone recalled. "He regaled us with his poems. I was brought up in an environment like that."[5] LaGrone credited his mother as a pillar in his artistic and emotional development.[6] "My parents had beautiful voices. I patterned my speech after theirs," LaGrone commented during a newspaper interview in his later years.[7]

The LaGrone family owned property and were community leaders. In 1929, repeated dangerously expressed jealousy over their accomplishments drove them to move from the several small towns in which they had hoped for peace in Okmulgee County, Oklahoma, to Albuquerque, New Mexico.[8]

College years, 1928-1938

editHoward University

editLaGrone's older brother, Hobart, had attended Fisk University. After graduation he worked in Washington, D.C., and in 1928 invited his younger brother, Oliver, to live with him while working for a degree.[9] In the fall Oliver LaGrone enrolled at Howard University, planning to become a lawyer.

LaGrone interacted closely with faculty member Dr. Carter G. Woodson, "Father of Black History". During the summer of 1929 he served as an assistant to Woodson, interviewing people in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas and Oklahoma for Woodson and Lorenzo Greene's upcoming volume, The Negro Wage Earner. Additionally, LaGrone sold books on black culture promoted by Dr. Woodson. Oliver LaGrone also absorbed interest in unionism from a political science faculty member, young Dr. Ralph Bunche.[10]

New Mexico

editThe country's Great Economic Depression led to LaGrone having to leave Howard University after completing only his first year. The precipitous death of his father, and the disabling effects on his mother of a car accident meant his earning power was essential at home.[11] LaGrone and his older brother, Hobart, opened a funeral parlor to help support the family. This opportunity to study anatomy later informed Oliver LaGrone's sculpting talents.[12][13] He also sang for three years with a semi-professional quartet on radio programs.[14]

LaGrone felt drawn to create, sculpting in the mahogany-like pinyon pine so plentiful in the New Mexico landscape. In 2005 the Unitarian Church of Harrisburg received a letter from an elderly New Mexican man who had met LaGrone while both were attending the University of New Mexico. He was hoping to find LaGrone's 1930 sculpture, "Black", carved from pinyon wood. Seventy-five years after first seeing the sculpture, he wrote, "I was shocked and speechless at the grandeur of the figure; then I walked around to look at the back of it and immediately started crying. This magnificent human being, standing so proud, had his hands chained behind his back. It was the most striking thing I had ever seen that depicted the condition of the black race living in this country. My emotional response broke down any barriers that might have existed between us. . . . During that period, there was no way I could buy any of his work, but if I could find the black man with chained hands, I would try to find whatever amount of money was required to own it for the few years I have left." The work had been long since purchased and later was given to the Detroit chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, but its image remained potent 75 years later.[15] "Black" was the same displayed sculpture that several years later led to LaGrone's return to college.[16] The sculpture is now privately held.

University of New Mexico

editOliver LaGrone was working in Albuquerque at odd jobs, and in the household of a civil engineer whose spouse admired LaGrone's gracious manner. After seeing one of his sculptures, she took LaGrone to the president of the University of New Mexico (UNM), to assure that the young black man would be enrolled. His previously un-nurtured artistic talent came to the fore when in 1934 he began to attend the University of New Mexico, majoring in sociology and minoring in fine arts. As teaching assistant to architect-sculptor, William Emmet Burk, Jr.,[12][17] he launched into a lifetime of expressed reflection on the intersection of sentiment and form.

Among LaGrone's UNM professors was a man who was friends with the roving journalist Ernie Pyle. From 1935 to 1941, Pyle was visiting America's small towns, creating Scripps-Howard syndicated newspaper columns as he went. The two men stopped by a university art exhibit which included work by LaGrone. Pyle then devoted one of his 1938 columns to LaGrone's sculptural talents.[18][19][20] "I know of nothing that would please me more than to have written the first piece in public print about a man who would someday be referred to all over the world as 'Oliver LaGrone--you know, the sculptor,'" wrote Pyle.[21]

Works Progress Administration

editLaGrone was among artists assisted by the Federal Art Project arm of the Works Progress Administration.[22][23] In 1937 he won a competition to create a sculpture[24] for the then new Carrie Tingley Children's Hospital,[25] an institution established to address the increasing incidence of infantile paralysis. The sculpture Mercy reflects LaGrone's Oklahoma memories of his mother caring for him during repeated and lengthy childhood bouts with malaria.[26] His 1937 cast marblestone sculpture was recast in bronze in 1991 for display in Albuquerque. One casting was placed in the Richardson Pavilion of the University of New Mexico hospital housing the previously relocated Tingley Hospital, on the floor dedicated to specialized care for children with orthopedic or chronic physical rehabilitation problems. Another casting of Mercy is displayed in the sculpture garden of the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History.[27][28]

Marriage

editLaGrone graduated from the University of New Mexico's School of Education in 1938 with a Bachelor of Science degree.[29] Also in 1938, he married Irmah Cooke, herself a budding playwright and poet.[30] Her father, James D. Cooke, had been the founder and editor of the Gary Sun, an Indiana newspaper. A decade earlier, he had been murdered after advocating that his African American readers not purchase from businesses where African Americans were forbidden to work.[31] To be near Mrs. LaGrone's remaining family, the couple took up residence in Michigan. There LaGrone joined the family real estate business. A daughter, Lotus Joy (married surname Johnson) was born in 1940.[32]

Art and unionism in Detroit, 1941-1953

editCranbrook Academy of Art

editBy 1941 the young family had moved to Detroit, to be near Mrs. LaGrone's remaining family. At his wife's encouragement, LaGrone explored Cranbrook Academy of Art in nearby Bloomfield Hills. The result of the inquiry was a personal invitation from faculty member Carl Milles, noted Swedish sculptor, to work as his protege. LaGrone thereby became the first African-American to attend Cranbrook, from November 1941 to July 1942.[33] [34] Milles arranged that LaGrone receive a McGregor Fund grant for advanced study in sculpture.[35] Milles supplemented the grant from his personal funds.[36] LaGrone's tuition was covered by a scholarship from the Student Aid Foundation of Michigan.[37] Cranbrook's archives received, after LaGrone's death, papers and photographs donated by his daughter in 1997, and, later, memorabilia from the scholarship established in his name.

United Auto Workers

editOliver LaGrone felt responsibility and desire to actively oppose the advance of fascism by participating directly in the U.S. effort in World War II. An old football injury prevented him from joining the armed services, so in 1942 he took a production job at Ford Motors' huge River Rouge complex. However, recurrent work accidents led to his employment with the United Auto Workers union. From 1943 to 1948, he was its director of visual education, supervising a department, and speaking and showing films to union auto workers across the country.

Internal tension between LaGrone's artistic side and his humanitarian sentiments resurfaced. His interests brought him into Detroit's renaissance of black artists, not unlike the Harlem Renaissance in New York. Both cultural movements focused on literature, music, theater, art and politics. During this time he wrote his first poetry, reflecting on his Detroit experiences. He gathered them into a collection for his 1949 volume Footfalls.[38]

During his union staff days, in 1947, he divorced.[39]

Paul Robeson

editLaGrone and Paul Robeson, the singer, actor and civil rights activist, knew each other. Their lives both included interests in football, law, and the arts. Robeson performed Shakespeare's Othello on Broadway in 1943, in the first-ever American production to feature a black actor with an otherwise all-white cast. When, during the Communist witch-hunting era of U.S. Senator Joe McCarthy, the Detroit Loyalty Committee asked LaGrone to inform on Robeson, LaGrone refused. Ensuing harassment and physical threats by Detroit police[40] also resulted in LaGrone's losing employment, forcing him to resort to selling pots and pans door-to-door to survive. Later, he drew on his personal relationship with Robeson, to create for The Pennsylvania State University's main campus, under commission from the PSU Alumni Association, a bust of Robeson.[41] Unveiled in 1986, it is featured in the Paul Robeson Cultural Center of the Student Union in State College, Pennsylvania.[42]

Public school teaching and more, 1954-1969

editPublic school teacher

editFrom 1954 through 1969, Oliver LaGrone taught in Detroit public schools. He was first an emergency substitute, then a specialist in arts and crafts, and, by 1967, a high school instructor in African-American history. From 1956 through 1960, he matriculated at Wayne State University, his post-baccalaureate work gaining him teacher certification in special education and in art.[43] His teaching was backdrop to his Detroit accomplishments in both art and poetry circles.[44]

Advocate and artist

editA photograph of LaGrone standing near Dr. Ethelene Crockett playing organ is telling, as it offers a tip-off to LaGrone's view on the link between advocacy and art.[45] The photo was taken at a Detroit gathering of civil rights activists, including Detroit resident Rosa Parks (seated right). LaGrone sculpted a bust of Dr. Crockett's noted spouse, civil rights activist, lawyer, judge, Congressman George Crockett, Jr. During this period LaGrone served for two years, 1968–1970, on the Michigan Council on the Arts. He served on the African Art Gallery Fund Committee of the Detroit Institute of Arts.[46] From 1964 on, he was a life member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.[47][48] "It occurred to me early on that you're not going to be satisfied until you find a way to combine your art with social commentary"[49] "To me the artist should put being a great human being before being an artist. Therefore, people, and the society in which they live, are important to me. I've always been torn between history and sociology on one hand and poetry and art on the other."[50]

Oliver LaGrone's poems appeared in The Negro Digest and the New York Times Sunday Book Review, as well as other publications. He was invited to read his poetry in public literary venues and in radio interviews.[51] Boone House, a black-initiated cultural center for artists in Detroit, saw him among its regular poetry readers.[52] In 1963 he published his volume They Speak of Dawns, celebrating the centennial year of the Emancipation Proclamation. A complementary pair of poems contrast the Freedom Rider and the astronaut, both harbingers of the future.[53] He was a member of a panel of poets at the 1966 Black Arts Convention in Detroit[54] and the same year won first prize in an annual Michigan poetry contest.[55] He appeared in seven poetry anthologies, including: Beyond the Blues, 1962; New Negro Poets: U.S.A., 1964; Poesie Negro Americain, 1964; Ten: An Anthology of Detroit Poets, 1965; For Malcolm, 1967; The Poetry of the Negro 1764-1970, 1970, Langston Hughes, Ed.; The American Equation, 1972, and The Study of Literature, 1978.[56]

A respected creator, LaGrone frequently exhibited art, juried art shows and lectured and served on panel discussions in the Detroit area.[57] LaGrone's 1958 sculpture, The Dancer, won a prize in an exhibit at Wayne State University. The piece was inspired by dancer, choreographer and anthropologist, Dr. Pearl Primus, pioneer American interpreter of African dance. Three years later, LaGrone sculpted Rev. Charles A. Hill,[58] known for his courageous, practical support of those who championed the cases of worker's and civil rights, long before those efforts became recognized social movements. LaGrone continued sculpting personally and took on private sculpting students.[59] In 1964, the Detroit chapter of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History commissioned of LaGrone a representation of the poet and writer Langston Hughes. Hughes had since the 1920s been noted as a leader in the Harlem Renaissance. Hughes' work celebrated the dignity and beauty of black life, in harmony with Oliver LaGrone's interests. Upon Hughes' death, as part of the poet's estate, the graceful lines of Hughes' face, sculpted by LaGrone, became part of the collections of the Schomburg Center.[60] The center is a New York Public Library research branch on black culture, where the sculpture is in reserve with the Art and Artifacts Division.[61]

African influence

editIn 1968 LaGrone was invited by friends in Togo to establish a base to from there explore the history of West African culture. Learning of the 1400s advanced cast bronzes of the historic kingdom of Benin, deepened his understanding of African art.[62] LaGrone much later stated to a reporter, "My African ancestors invented the lost-wax method of casting, so whenever I work in bronze I am reminded that I am carrying on the work begun by my people."[63] And, "I work in bronze because that was the metal of my ancestors. Don't tell me they didn't possess a sophisticated knowledge of metallurgy".[64]

By 1970 the Detroit City Council recognized both LaGrone's "academic standing and artistic gift" and "his human sensitivity to personal, social and cultural issues".[46] The commendation was presented at a testimonial dinner given by "Friends of Oliver LaGrone" as he prepared to leave Detroit.[65]

On the road

editIntroduction to comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory, who had already been drawing on portions of LaGrone's poetry in some of his presentations, inspired a new development for Oliver LaGrone. Personally encouraged by Gregory, LaGrone created "Odyssey of the Afro-American and His Art", a series which would take him across the country to scheduled speaking engagements in 24 states, arranged through the American Program Bureau.[12][66] Traveling with a selection of his sculptures, he would describe their inspiration and creation, recite his relevant poetry, and promote respect for black culture and history. The lectures and gallery talks addressed topics such as, "The Odyssey of the Afro-American and his Art", "The Black Aesthetic", "Black Protest, Art, and Western Humanism", and "History's Roots in Art". Through realistic sculptures of black faces he focused on black contributions to America, drawing on the enduring fraternity of creative spirits from all cultures in all times.[67]

Pennsylvania State University, 1970-1976

editFaculty member

editOne such trip for Oliver LaGrone's art-culture presentations took him through Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. He was invited by a friend on the faculty at the capitol campus of The Pennsylvania State University (PSU) to speak to his class. That led in 1970 to LaGrone's being solicited to offer studio art classes and to lecture on African American history. In 1972 he was appointed Special Assistant to the PSU Vice-president for Undergraduate Affairs.[68] In 1974–1975, he served as Artist-in-Residence at PSU, traveling to offer art seminars at all of its then twenty-one campuses. By then, his large sculpture, University as Family, was installed on the library lawn of PSU Scranton .[69][70] With permission, he modeled the youngest of the four figures on the face of the daughter of friends.[71]

LaGrone was also the featured speaker at the annual convention of the National Federation of State Poetry Societies in June 1974.

Representing PSU

editIn 1975 LaGrone was asked to represent PSU on the 21-member Pennsylvania Bicentennial Commission.[72] He is included in a 1976 volume, sponsored by Henry Ford III, featuring 100 African American leaders. The cover is a picture of LaGrone, former Ford employee and former auto workers' union staffer.[73] The LaGrone Cultural Arts Center in the Olmsted Building at Penn State Harrisburg features several of the artist's sculptures, including The Dancer. A smaller version of University as Family, at PSU Scranton, is in the Harrisburg campus's Rowland Sculpture Garden, located behind the Olmsted facility. LaGrone's bust of Paul Robeson graces the black student offices within the student union at the PSU main campus in State College, Pennsylvania. During his Pennsylvania years, Oliver LaGrone lived in the state capital, Harrisburg. The city's mayor proclaimed February 3, 1983 to be "Oliver LaGrone Day". In 1984 his respect for all brought him a position on the city's Human Relations Commission.[74] The "LaGrone Day" recognition was repeated in 1993.[75]

Active retirement, 1977-1995

editRetiring from PSU, LaGrone established a sculpting studio in the Educational-Cultural Center of Hershey, Pennsylvania, teaching children and adults.[76] Later, he continued to sculpt and teach, 1980–1983,[77] as artist-in-residence for the Boas Center for Learning, a program in the Harrisburg School District administered by the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts[78] through a grant received from the National Endowment for the Arts.[79] In 1986, the Pennsylvania Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) Holiday Commission presented LaGrone's MLK bust to the state museum.[80][81][82] He published the volume Dawnfire and Other Poems in 1989.[12] Columnist Chuck Stone wrote, "An awesome renaissance man -- sculptor, poet, writer, painter, scholar, laborer, inventor and teacher. Oliver LaGrone is a towering intellect, a man of prodigious creativity and physical vigor."[83]

Single since 1947, LaGrone had in 1976 married Lillian Pauline Mitchell Graham,[2][84] retired principal of an Erie, Pennsylvania public school.[55] They moved to Albuquerque in 1977, then Harrisburg, and in 1986 moved to Hamlet, North Carolina, Mrs. LaGrone's family home.[85] LaGrone divorced again in 1992 and moved back to Detroit.[12]

A syndicated newspaper columnist wrote, "He is a charmer, Oliver LaGrone. He is also an elegant man and eloquent speaker, with a knowing spirit. He sprinkles his prose with poetry. Of himself he softly incants: 'Out of the amorphous or chaotic he coaxes order, form, beauty. He is a creator of 3-D communications.'"[86]

LaGrone was active with the Unitarian Church of Harrisburg (UCH)[87] from 1975 to 1986. His bust of Harriet Tubman (cast bronze) was purchased for the church by friends and he gave the bust George Washington Carver (plaster, bronze patina) to UCH. The church has also been gifted two other LaGrone sculptures. Ballet to Disco[88] (cast bronze) is composed of two separate figures, mounted so their complementary positions can be opposed in multiple ways, as intended by LaGrone. Mask[89] (plaster, bronze patina) is an African-themed wall piece. Members recall LaGrone's positive outlook and adroit observations, as when he once responded in conversation, "Forgive me. I'm as thick as the Peruvian jungle".[90] His physical strength and singing of "Old Man River" became personal hallmarks as well.[91] At age 82, LaGrone, a boxer and football player in his youth, still had "a grip like a vice, as strong as a crocodile's bite" observed the minister.[92]

While living near his daughter and family in Detroit, LaGrone hosted civil rights activist Rosa Parks at his 87th birthday party.[93] Still sculpting and writing poetry, LaGrone died at age 89, on October 15, 1995.[94]

Two and a half years after Oliver LaGrone's death, about two-hundred people gathered at PSU Harrisburg in March 1998, to celebrate his life contributions. It was also a dedication renaming the Minority Student Center in the student union, the LaGrone Cultural Arts Center. A PSU official stated, "Oliver was very charismatic, very approachable. He had a command of the English language. He could see art in everything. He was so warm."[95] A newspaper interviewer described him as, "urbane, gracious, graceful . . . [with a] melodious, hypnotic voice"[96] Sixteen years later the university honored LaGrone's impact with another organized gathering.[97]

Oliver LaGrone Scholarship

editOliver LaGrone in 1974 inspired the creation of a scholarship program in his name.[98][55] The scholarship founders were primarily from the Unitarian Church of Harrisburg. LaGrone donated the proceeds from the sale of a bronze casting of The Dancer. Other monies to establish and build the scholarship came from fundraisers large and small, with the donations of many individuals and organizations in the years to follow. A newspaper quoted LaGrone in 1986, advising young people, "Read. Read. Read. Lives of great men and women all remind us that, when you find an area of interest, work, work, to know all you can about it and learn to both give and receive graciously."[99]

The Oliver LaGrone Scholarship program was reconfigured in 1991, focusing funds on one graduate of Harrisburg High School. It annually offers the largest local scholarship[100] available to a graduate of the city's public high school.

LaGrone sculptures

editPublicly accessible

edit- Mercy, 1937, marblestone cast 1937, bronze cast 1991. University of New Mexico Hospitals, Albuquerque, Carrie Tingley Hospital, Richardson Pavilion, 5th-floor inpatient lobby; also at Albuquerque Museum, sculpture garden.[101] Casting in 1991 courtesy of the National New Deal Preservation Association and estate of Naomi Ashley.[102] 48" h. x 27" w. x 36" d.

- Bust of George Washington Carver, 1950, plaster, bronze patina. Unitarian Church of Harrisburg since 1973; possibly cast bronze for former G.W. Carver School, Oakdale Gardens, Detroit. 17" h. x 12" w. x 10" d.

- The Dancer, 1958, cast bronze, LaGrone Cultural Arts Center, Pennsylvania State University Harrisburg, W132 Olmsted Bldg.; also at PSU Scranton library; also at City Hall, City of Harrisburg.[103] Inspired by dancer, choreographer and anthropologist, pioneer American interpreter of African dance, Dr. Pearl Primus. LaGrone further wrote a poem about this hero.[104]

- Bust of Reverend Charles A. Hill, Sr., 1961, cast bronze, Hartford Memorial Baptist Church, Detroit.[105]

- Head of Langston Hughes, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York City Libraries. Viewing by appointment,.[106] 11" h. x 8.5" w. x 10.5" d.

- Bust of Harriet Tubman, bef. 1974, cast bronze. LaGrone Cultural Arts Center, Pennsylvania State University Harrisburg, W132 Olmsted Building; also at Unitarian Church of Harrisburg, foyer. 14.5"h. x 11" w. x 9.5" d.

- The University as Family, 1975, cast bronze. Pennsylvania State University Scranton, library lawn; smaller form in Pennsylvania State University Harrisburg, Olmsted Building rear, Rowland Sculpture Garden, dedicated October 11, 1993;[46][107] 28" h. x 12" w. x 8" d. Youthful Kathryn Fritz a model for the child.

- Ballet to Disco, 1979, cast bronze, two figures,.[108] 17.5" h. x 11" w. x 9" d.

- Mask, 1980, plaster, bronze patina, African motif wall-piece. Unitarian Church of Harrisburg. 20" h. x 10" w. x 2" d.,

- Bust of Paul Robeson, abt. 1985, cast bronze. Pennsylvania State University (University Park), Robeson Cultural Center, commissioned by PSU Alumni Association, presented April 12, 1986.[46] (see LaGrone's "Lines to the Black Oak" in New Black Voices, ed. Abraham Chapman (New York: Mentor-New American Library, 1972))

- Bust of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., bef. 1986, cast bronze. Pennsylvania State Museum, presented June 29, 1986.[46] Reserve, Catalogue #86.45;

- Bust of Dr. Carter G. Woodson, plaster, bronze patina. LaGrone Cultural Arts Center, Pennsylvania State University Harrisburg, W132 Olmsted Bldg.; gifted by Lotus Joy LaGrone Johnson, Oliver LaGrone's daughter, on the dedication of the renamed Center, 1998.

Privately held

editAt least thirty-six other LaGrone sculptures are privately held, carved from pinyon pine or Honduras mahogany, molded in plaster and painted with a bronze patina, or cast in marblestone or bronze. The works, created from 1930 to at least 1994, include bas reliefs, twelve busts, and statuary up to forty-eight inches in height. African American themes of resilience and achievement predominate. Frederick Douglass, Aretha Franklin, Rosa Parks, and Sojourner Truth are among the persons represented. LaGrone said, ."I have been faced with the need of saying something about the black presence in America . . . [as] a way to touch the psyche of America."[109] "If America is to accept what she is morally, she has to accept the contributions of such men as Frederick Douglass and such women as Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth."[110] Detail regarding various privately held sculptures is available through the Unitarian Church of Harrisburg.[111]

LaGrone poetry

edit- Footfalls: Poetry From America's Becoming, 1949, Pennsylvania State University, Special Collections Library (UP). Available by appointment, 104 Paterno, Brockson, PS356F55. Also held by other academic libraries.

- "They Speak of Dawns: A Duo-Poem Written for the Centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, 1863-1963", 1963, Pennsylvania State University, Special Collections Library (UP). Available by appointment, 104 Paterno, Brockson, PS3562.A285T45. Also held by other academic libraries.

- Dawnfire and Other Poems, 1989, Pennsylvania State University, Special Collections Library (UP). Available by appointment, 104 Paterno, Brockson, PS3562.A314D3, 1989. Also held by other academic libraries.[112]

Images

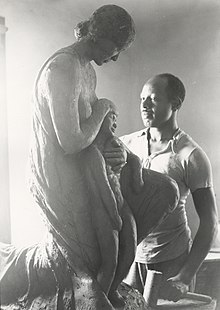

edit- Mercy, in the process of being cast in plaster by creator Oliver LaGrone, in 1937. The action photo of the WPA sculptor and University of New Mexico graduate is held by the Palace of Governor's digital photo archive, a department of the state's New Mexico History Museum. Accompanying newspaper articles describe columnist Ernie Pyle's admiration for LaGrone's talents, "Ex-student Hailed As Sculptor" (left of sculpting photo) and LaGrone's 1987 return to repair the much-loved work before it was recast, in bronze, "Detroit Sculptor Ends Visit Here". Neighboring photos in the group of five address the brother, Hobart, with whom LaGrone learned anatomy.[113]

- Mercy, here in the sculpture garden of the Albuquerque Museum.[114] Two bronze castings were made, in 1991, honoring the work's WPA heritage. LaGrone had been asked in 1987 to come to Albuquerque to restore the sick child's much-rubbed toe on his original sculpture, and to speak at the 50th anniversary of Carrie Tingley Hospital.[115] Child patients there today, now a specialized component of the University of New Mexico Hospitals, are also assured the continuing succor of LaGrone's sculpture.[116]

- Bust of Reverend Charles Andrew Hill, Sr., pastor of Hartford Memorial Baptist Church in Detroit for 48 years, was known for his courageous, practical support of those who championed the causes of worker's and civil rights, long before those efforts became recognized social movements. See image by scrolling past several photos with text to LaGrone's "The Bronze Portrait of Charles A. Hill. Sr."[117]

- LaGrone sculpting at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, under the tutelage of internationally recognized faculty member Carl Milles, November 1941 to July 1942. Milles had studied with sculptor Auguste Rodin. For multiple images within Cranbrook Archives, at Digital Image Database; enter 'LaGrone' in the search box.[118]

- While teaching in Detroit public schools, LaGrone continued to sculpt. An advocate for universalism, his work celebrated African-Americans of significant contribution to American life. Detroit Institute of Arts, 1960s. At the institute's webpage, go to Art, Collections; enter 'LaGrone' in the search box. Sculptures pictured, left to right: on floor, tall, Heritage; at sculptor's elbow, Oedipus Reckless; on floor, Bust of George Washington Carver; Father and Son; The Dancer.[119]

- LaGrone read his poetry regularly during public performances with other noted black Detroit poets. A 1965 photo records him seated on the left, Melvin Tolson in the center, and Dudley Randall on the right.[120]

- Early in LaGrone's tenure at The Pennsylvania State University Harrisburg, he wrote a poem honoring an African American staff secretary who felt racism at work.[121]

- LaGrone's University as Family, is in near-life size on The Pennsylvania State University campus at Scranton.[122] LaGrone also gave the work in smaller form to the PSU Harrisburg campus.[123] It is today installed there in the sculpture garden behind the Ohlmsted building.[124]

- A 1989 interview with LaGrone is featured in a video outlining his social-justice-informed artistic accomplishments as the inspiration for the Oliver LaGrone Scholarship.[125] Note that when LaGrone sings "Old Man River" to underlie the video's close, the lyrics he uses are those reshaped by actor and singer Paul Robeson after the Jerome Kern song first appeared, in the 1939 movie "Showboat". Instead of 'old man river' accepting without care his lack of freedom, what LaGrone sings champions universal rights.

References

edit- ^ Public Opinion, Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, "People who teach are the luckiest people in the world", February 21, 1981, p. 8; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ a b South, Gail T., Oliver LaGrone: Time Walker, a Masters thesis for The Pennsylvania State University Harrisburg, 1976, ch. 1, pp.3-4. In preparation for writing the thesis, Gail South, in addition to studying LaGrone's poetry and sculptures, taped interviews with him over the course of a year. The interactions give potency to her descriptions of his developing emotions and thought processes. In 2013 the thesis was reprinted and updated by the committee administering the Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Fund of the Unitarian Church of Harrisburg. Throughout this article, references to the work use the page numbers from the reprinted work, with chapter numbers also citing location in the original.

- ^ Press Journal, Middletown, Pennsylvania, "Sculptor Oliver LaGrone Recalls a Mother's Note", Vol. 85, No. 35, August 27, 1975, pp. 1-2; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Myers, Julia R., Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 Through the Black Arts Movement, Eastern Michigan University Art Galleries, 2020, p.10; Myers treats LaGrone in a distinct section, as well as in embedded references to Harold Neal's respect for LaGrone the man and artist.

- ^ Albuquerque Journal, Albuquerque, New Mexico, "Ex-N.M. Sculptor LaGrone Hard at Work at 87", January 16, 1994, Section G, p.9, by Marsha Miro for Knight-Ridder newspapers; copy from Albuquerque Museum files in Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ "A Prince Hall Place Resident Profile: Oliver LaGrone", Prince Hall Place newsletter, Detroit, Winter 1994; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Middletown Press Journal, Middletown, Pennsylvania, "Sculptor Oliver LaGrone Recalls A Mother's Note", August 31, 1973; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 1, p. 5 and ch. 3, p. 12

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 2, p.9

- ^ Time Walker. ch. 2., p. 11

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 4, p. 13

- ^ a b c d e "Celebrating An Artist's Life", memorial service program, Detroit, October 21, 1995

- ^ Washington Daily News, "Howard University Boy Undertaker While Seeking Art Fame", April 21, 1928

- ^ C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Correspondence to the Unitarian Church of Harrisburg from Wallace Thorp, February 28, 2005; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills,, Michigan

- ^ The Patriot, "Children Throng Artist's Class", Feb. 18, 1973, p. 3

- ^ Architect, sculptor, designer and teacher; Burk described further at http://www.askart.com

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 4, pp. 14-15

- ^ Albuquerque Tribune,"Seeing New Mexico", 1938; LaGrone Curriculum Vitae 1988, LaGrone Art Culture Programs

- ^ Correspondence from Ernie Pyle to Oliver LaGrone, May 21, 1938, copy from Albuquerque Museum artist files; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Philadelphia Daily News, "LaGrone: a 'Living Legend in Black'", April 30, 1982, by Chuck Stone; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ [1]

- ^ WPA photo of LaGrone sculpting in New Mexico, taken in 1930s by Kelly Williams, not indexed until 1958

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3][permanent dead link]

- ^ LaGrone letter to Greg Johnson, Director, Public Relations, Carrie Tingley Hospital, University NM, Albuquerque, New Mexico, June 3, 1985; copy from Albuquerque Museum file on LaGrone; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ [4]

- ^ Flynn, Kathryn A. and Andrew Connors, Treasures on New Mexico Trails: Discover New Deal Art and Architecture Sunstone Press, 1995.

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 4, p. 15

- ^ Irmah Cooke Zampty memorial service program and obituary, March 26, 1994, Detroit, Michigan; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 5, p.16

- ^ Celebrating An Artist's Life, memorial service program, Detroit, October 21, 1995, C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ [5][permanent dead link]

- ^ Cranbrook Archives also hold audio interviews with LaGrone, available for research by appointment with the archives.

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 5, pp. 16-17

- ^ Unitarian Universalist World, "UU sculptor has 'worked out of many bags'", Unitarian Universalist Association: Boston, Massachusetts, August 15, 1977, pp. 1-2; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Cranbrook Academy of Art, C. Oliver LaGrone application, 1941

- ^ Timewalker ch. 6, pp. 19-22

- ^ Timewalker, ch. 6, p.23

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 6, pp.20-23

- ^ LaGrone Art Culture Programs, Curriculum vitae, 1987; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Minority Arts Committee, Student Union, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania , "Mr. Oliver LaGrone: Sculptor Poet, Lecturer", lecture publicity, February 1, 1987, Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Timewalker, ch. 7, pp. 24-26

- ^ Myers, Julia R., Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 Through the Black Arts Movement, Eastern Michigan University Art Galleries, 2020, p. 19

- ^ [6]

- ^ a b c d e Minority Arts Committee, Student Union, Pennsylvania State University Harrisburg, "Mr. Oliver LaGrone: Sculptor, Poet, Lecturer", lecture publicity, February 1, 1987

- ^ LaGrone Art Culture Program brochure, 1987; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ The Anson Record, "LaGrone to Exhibit", May 15, 1990, C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Philadelphia Daily News, LaGrone: a 'Living Legend in Black, by Chuck Stone, April 20, 1982

- ^ Press and Journal, Sculptor Oliver LaGrone Recalls A Mother's Note, Middletown, Pennsylvania, August 27, 1975

- ^ Boyd, Melva Joyce, Wrestling with the Muse: Dudley Randall and the Broadside Press. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003. p. 136.

- ^ Abandon Automobile: Detroit City Poetry 2001. ed., Melba Joyce Boyd and M.S. Liebler, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2001. p. 28

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 7, p. 25

- ^ Negro Digest, Vol. 15, No. 10, p. 55 (within convention article, pp. 54-58)

- ^ a b c Deccolades, 10th Anniversary Celebration program, Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Fund; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ LaGrone Art Culture Programs: Oliver LaGrone Curriculum Vitae" (likely printed 1987); Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ LaGrone in "Neal", p.19

- ^ Rev. Charles A. Hill

- ^ Celebrating An Artist's Life, memorial service program, Detroit, October 21, 1995; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ plaque on base states: "Presented to Langston Hughes by the Detroit Branch of the Association for Study of Negro Life and History, National Negro History Week Celebration, February 9, 1964, Sculptor, Oliver LaGrone"

- ^ New York City Public Library, Schomburg Center, Art and Artifacts Division, 212-491-2241 for viewing appointment

- ^ Timewalker, ch. 6, p. 27

- ^ Albuquerque Journal, "Sculptor Restores 'Mercy'", Section C, p. 1, May 8, 1987, by Bonnie Christina Celine; copy from Albuquerque Museum file on LaGrone; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Philadelphia Daily News, LaGrone: a 'Living Legend in Black, April 30, 1982, p. 44, by Chuck Stone; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ The Hershey Star, 'Oliver LaGrone: Resident Sculptor At Educational-Cultural Center', by Nancy Zell, sec. 2, p. 1, Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 9, p. 30

- ^ LaGrone Art Culture Programs: Oliver LaGrone Curriculum Vitae, likely printed 1987; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Shackley, Ann Allen and Sue P. Chandler, Living Black American Authors: A Biographical Dictionary, New York: R.R. Bowker, 1973, p. 39

- ^ [7]

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 9, pp. 30-31

- ^ Personal account, Dr. Paul and Lydia Fritz, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, April 27, 2016, in "Memories of Oliver LaGrone: Conversations" by Cordell Affeldt recounting LaGrone admirers' remarks, Nov 13, 2012;Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 9, p. 31

- ^ Living Legends in Black, Edward J. Bailey II, ed., Detroit Bailey Publishing Co., 1976

- ^ Timewalker, Epilogue, p.48

- ^ framed 1993 proclamation displayed at Unitarian Church of Harrisburg

- ^ The Hershey Star, "Oliver LaGrone: Resident Sculptor At Educational-Cultural Center", March 6, 1975, Sec. 2, p. 1; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Papers, Cranbrook Archive, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ LaGrone Art-Culture Program brochure, 1986; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomington Hills, Bloomington Hills, Michigan

- ^ Pennsylvania Council on the Arts

- ^ 'Timewalker', Epilogue, p. 48

- ^ Minority Arts Committee, Student Union, PSU Harrisburg, "Mr. Oliver LaGrone: Sculptor, Poet, Lecturer, lecture publicity, Feb. 1, 1987, Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ State Museum of Pennsylvania, Reserve, Catalogue #86.46

- ^ state_museum

- ^ Philadelphia Inquirer-Daily News, "LaGrone, A Living Legend", by Chuck Stone, April 30, 1982

- ^ Time Walker, Chronology, p, iv

- ^ Philadelphia Inquirer, "For sculptor, 87, essential elements are clay and time", pp. F1, F3, February 18, 1994

- ^ Albuquerque Journal,"Ex-N.M. Sculptor LaGrone Hard at Work at 87", Section G, p. 9, January 16, 1994, by Marsha Miro, Knight-Ridder newspapers

- ^ Unitarian Church of Harrisburg, 1280 Clover Lane, Harrisburg, PA 17113; 717-564-4761; harrisburguu.org

- ^ Gifted by UCH members, LaGrone scholarship founder Lowery, and Marilyn McHenry in 1999

- ^ Gifted by former UCH members Dr. Paul and Lydia Fritz, early LaGrone scholarship activists, in 2016

- ^ Personal account, Marilyn McHenry, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, April 27, 2016; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Personal email, David Powell, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, August 15. 2016; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ The Sentinel (Carlisle, Pennsylvania), "Sculptor proves 'universality' knows no color", by Cynthia Jacobsen, May 20, 1989, sec. D, pp. 1-2; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archive, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Prince Hall Place Newsletter", "Clarence Oliver LaGrone", Winter 1993-1994; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomington Hills, Michigan

- ^ 'Time Walker', Epilogue, p. 48

- ^ Patriot-News, "Center at Penn State Harrisburg to be renamed for Oliver LaGrone,", April 12, 1998, p. I8

- ^ Middletown Press-Journal, 'Sculptor Oliver LaGrone Recalls A Mother's Note', August 31, 1973; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ [8]

- ^ scholarship program in his name (see Education list, drop-down LaGrone Scholarship)

- ^ Richmond County Daily Journal, Rockingham North Carolina, 1986; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ The Burg, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, "A Legacy of Learning: Artist Oliver LaGrone devoted his life to teaching others. A scholarship in his name ensures that his work continues." July 31, 2014 (http://www.theburgnews.com/tag/oliver-lagrone)

- ^ Flynn, Kathryn A. and Andrew Connors, Treasures of New Mexico Trails: Discover New Deal Art and Architecture, Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunshine Press, 1995

- ^ Time Walker, ch. 13, p. 40

- ^ Time Walker Chronology iv

- ^ Time Walker, Poems, p. 62.

- ^ Hartford Memorial Baptist Church, Detroit.

- ^ Arts and Artifacts Division, 212-491-2241

- ^ Time Walker, Chronology, iv, and ch. 13, p. 41

- ^ individualized mounting designed and constructed by UCH member John Quimby

- ^ "Oliver LaGrone: Artist, Educator, Humanitarian", compact disc produced by Unitarian Church of Harrisburg (Pennsylvania), including a 1989 interview.

- ^ The Sentinel (Carlisle, Pennsylvania), Sculptor proves 'universality' knows no color, by Cynthia Jacobson, May 20. 1989, sec D, p. 1

- ^ Unitarian Church of Harrisburg

- ^ South, Gail. Oliver Lagrone:: Time Walker. Penn State University.

- ^ [9]

- ^ [10]

- ^ "Oliver LaGrone Honored By Hospital", 1990; C. Oliver LaGrone Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ Campus News, "WPA art conserved, reinstalled on Tingley hospital first floor", Feb 16, 2004; Oliver LaGrone Scholarship Committee Papers, Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- ^ [11]

- ^ [12]

- ^ [13]

- ^ [14]

- ^ [15]

- ^ [16]

- ^ [17]

- ^ [18]

- ^ [19]