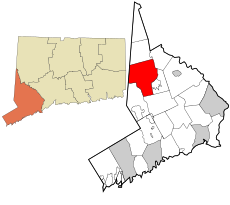

Danbury (/ˈdænbɛəri/ DAN-bair-ee) is a city in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States, located approximately 50 miles (80 km) northeast of New York City. Danbury's population as of 2020 was 86,518. It is the third-largest city in Western Connecticut, and the seventh-largest city in Connecticut.[3] Located within the heart of the Housatonic Valley region, the city is a commercial hub of western Connecticut, an outer-ring commuter suburb of New York City, and an historic summer colony of the New York metropolitan area and New England.[4]

Danbury | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: The Hat City | |

| Coordinates: 41°24′08″N 73°28′16″W / 41.40222°N 73.47111°W | |

| Country | United States |

| U.S. state | Connecticut |

| County | Fairfield |

| Region | Western CT |

| Incorporated (town) | 1702 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1889 |

| Consolidated | 1965 |

| Villages/Neighborhoods | Beaverbrook Beckettville Germantown Great Plain Hayestown Long Ridge King Street Lake Waubeeka Mill Plain Miry Brook Pembroke Wooster Heights |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Roberto Alves (D) |

| Area | |

• City | 44.19 sq mi (114.45 km2) |

| • Land | 41.95 sq mi (108.64 km2) |

| • Water | 2.24 sq mi (5.81 km2) |

| • Urban | 123.6 sq mi (320.1 km2) |

| Elevation | 397 ft (121 m) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

• City | 86,518 |

| • Density | 2,062.4/sq mi (779.56/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Codes | 06810–06811, 06813 |

| Area code(s) | 203/475 |

| FIPS code | 09-18430 |

| GNIS feature ID | 206580 |

| Airport | Danbury Municipal Airport |

| Interstates | |

| U.S. Highways | |

| State Routes | |

| Commuter rail | |

| Website | www |

Danbury is nicknamed the "Hat City", because it was once the center of the American hat industry, during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The mineral danburite is named after Danbury, while the city itself is named for Danbury in Essex, England.[5]

Danbury is home to Danbury Hospital, Western Connecticut State University, Danbury Fair Mall, and Danbury Municipal Airport.

History

editDanbury was settled by colonists in 1685, when eight families moved from what are now Norwalk and Stamford, Connecticut. The Danbury area was then called Pahquioque by its namesake, the Algonquian-speaking Pahquioque Native Americans (they are believed to have been a band of the Paugusset people), who occupied lands along the Still River. Bands were often identified by such geographic designation but they were associated with the larger nation by culture and language).

One of the original settlers in Danbury was Samuel Benedict, who bought land from the Paquioque in 1685, along with his brother James Benedict, James Beebe, and Judah Gregory. This area was also called Paquiack ("open plain" or "cleared land") by the Paquioque.[6] In recognition of the wetlands, the settlers chose the name Swampfield for their town. In October 1687, the general court decreed the name Danbury. The general court appointed a committee to lay out the new town's boundaries. A survey was made in 1693, and a formal town patent was granted in 1702.

During the Revolutionary War, Danbury was an important military supply depot for the Continental Army. Sybil Ludington, 16-year-old daughter of American Colonel Henry Ludington, is said to have made a 40-mile ride in the early hours of the night on April 26, 1777, to warn the people of Danbury and her father's forces in Putnam County, New York, of the approach of British regulars, helping them muster in defense; these accounts, originating from the Ludington family, are questioned by modern scholars.[7][8][9]

During the following day on April 26, 1777, the British, under Major General William Tryon, burned and sacked Danbury, but fatalities were limited due to Ludington's warning. The central motto on the seal of the City of Danbury is Restituimus, (Latin for "We have restored"), a reference to the destruction caused by the Loyalist army troops. The American General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield by the British forces which had raided Danbury, but at the beginning of the battle, the Americans succeeded in driving the British forces down to Long Island Sound.[10] Wooster is buried in Danbury's Wooster Cemetery; the private Wooster School in Danbury also was named in his honor.

In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, a group expressing fear of persecution by the Congregationalists of that town, in which he used the expression "Separation of Church and State". It is the first known instance of the expression in American legal or political writing. The letter is on display at the Unitarian-Universalist Congregation of Danbury.

The first Danbury Fair was held in 1821. In 1869, it became a yearly event; the last edition was in 1981. The fairgrounds were cleared to make room for the Danbury Fair Mall, which opened in autumn 1986.[11]

In 1835, the Connecticut Legislature granted a rail charter to the Fairfield County Railroad, but construction was delayed because of lack of investment. In 1850, the organization's plans were scaled back, and renamed the Danbury and Norwalk Railroad. Work moved quickly on the 23 mi (37 km) railroad line. In 1852, the first railroad line in Danbury opened,[12] with two trains making the 75-minute trip to Norwalk.

The central part of Danbury was incorporated as a borough in 1822. The borough was reincorporated as the city of Danbury on April 19, 1889. The city and town were consolidated on January 1, 1965.

The first dam to be built on the river, to collect water for the hat industry, impounded the Kohanza Reservoir. This dam broke on January 31, 1869, under pressure of ice and water. The ensuing flood of icy water killed 11 people within 30 minutes, and caused major damage to homes and farms.[13]

As a busy city, Danbury attracted traveling shows and tours, including Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in 1900. It featured young men of the Oglala Sioux nation, who re-enacted events from frontier history. Oglala Sioux Albert Afraid of Hawk died on June 29, 1900, at age 21 in Danbury during the tour. He was buried at Wooster Cemetery. In 2012, employee Robert Young discovered Afraid of Hawk's remains. The city consulted with Oglala Sioux leaders of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and arranged repatriation of the remains to the nation. This meeting occurred in the Health Sciences Library of Danbury Hospital with assistance of the Chaplain. Wrapped in a bison skin, the remains were transported to Manderson, South Dakota, to Saint Mark's Episcopal Cemetery, for reburial by tribal descendants.[14][15]

In 1928 local plane pilots bought a 60-acre (24 ha) tract near the Fairgrounds, known as Tucker's Field, and leased it to the town. This was developed as an airport, which is now Danbury Municipal Airport (ICAO: KDXR).

Connecticut's largest lake, Candlewood Lake (of which the extreme southern part is in Danbury), was created as a hydroelectric power facility in 1928 by building a dam where Wood Creek and the Rocky River meet near the Housatonic River in New Milford.

During World War II, Danbury's federal prison was one of many sites used for the incarceration of conscientious objectors. One in six inmates in the United States' federal prisons was a conscientious objector, and prisons like Danbury found themselves suddenly filled with large numbers of highly educated men skilled in social activism. Due to the activism of inmates within the prison, and local laborers protesting in solidarity with the conscientious objectors, Danbury became one of the nation's first prisons to desegregate its inmates.[16][17][18]

On August 18–19, 1955, the Still River, which normally meandered slowly through downtown Danbury, overflowed its banks when Hurricane Diane hit the area, dropping six inches of rain on the city. This was in addition to the nine inches that fell from Hurricane Connie five days earlier.[19] The water flooded stores, factories and homes along the river from North Street to Beaver Brook, causing $3 million in damages. Stores downtown on White Street between Main and Maple were especially hard hit. On October 13–16, another 12 inches of rain fell on Danbury, causing the worst flooding in the city's history. This time, the river damaged all bridges across it, effectively cutting the city in half for several days. Flooding was more widespread than in August, and the same downtown areas hit in August were devastated once again. The resulting damage was valued at $6 million, and two people lost their lives. The City determined the river in the downtown area had to be tamed. $4.5 million in federal and state funding were acquired as part of a greater urban renewal project to straighten, deepen, widen, and enclose the river in a concrete channel through the downtown. At the same time, roads were relocated and rebuilt, 123 major buildings were razed and 104 families were relocated. This began various efforts by the City through 1975 towards urban renewal, using another $22 million of federal funding. However, these efforts failed to reinvigorate the central business district.[20]

On February 13, 1970, brothers James and John Pardue detonated time bombs (injuring 26 people) at the police station, Union Savings Bank and in their getaway car to cover their escape from robbing the bank at gunpoint, the culmination of a two-year crime spree that included four bank robberies and five murders.[21]

The flawed primary mirror of the Hubble Space Telescope was ground and polished in Danbury by Perkin-Elmer's Danbury Optical System unit from 1979 to 1981. It was mistakenly ground to the wrong shape due to the use of a miscalibrated testing device. The mistake was not discovered until after the telescope was in orbit and began to be used. The effects of the flaw were corrected during the telescope's first servicing mission in 1993.

In the August 1988 issue of Money magazine, Danbury topped the magazine's list of the best U.S. cities to live in, mostly due to low crime, good schools, and location.[22]

A case that would make national headlines and play out for over four years began on September 19, 2006, when eleven day laborers, who came to be known as the "Danbury 11", were arrested in Danbury. A sting operation had been set up where day laborers were lured into a van whose driver, a disguised Danbury police officer posing as a contractor, promised them work. The laborers were driven to a parking lot where, if it was determined they were in the US illegally, were arrested by agents of ICE and the Danbury police. Yale University law students represented the men pro bono and filed a civil rights lawsuit against the city on their behalf. On March 8, 2011, it was confirmed a settlement had been reached in the case whereby Danbury agreed to pay the laborers $400,000 (Danbury's insurance carrier paid the settlement plus legal fees of close to $1,000,000, less a $100,000 deductible). The federal government agreed to pay them $250,000. As part of the settlement, the City did not admit any wrongdoing and there were no changes in the city's policies or procedures.[23][24][25]

Hatmaking in Danbury

editIn 1780, what is traditionally considered to be the first hat shop in Danbury was established by Zadoc Benedict. (Hatmaking had existed in Danbury before the Revolution.) The Benedict shop had three employees, and they made 18 hats weekly.[26][27][28]: 47–48 By 1800, Danbury was producing 20,000 hats annually, more than any other city in the U.S.[29] Due to the fur felt hat coming back into style for men and increasing mechanization in the 1850s, by 1859 hat production in Danbury had risen to 1.5 million annually. By 1887, thirty factories were producing 5 million hats per year.[28]: 52 Around this time, fur processing was separated from hat manufacturing when the P. Robinson Fur Cutting Company (1884) on Oil Mill Road and the White Brothers' factory began operation.[29]

By 1880, workers had unionized, beginning decades of labor unrest. They struggled to achieve conditions that were more fair, going on strike; with management reacting with lockouts. Because of the scale of the industry, labor unrest and struggles over wages affected the economy of the entire town. In 1893, nineteen manufacturers locked out 4000 union hatters. In 1902, the American Federation of Labor union called for a nationwide boycott of Dietrich Loewe, a Danbury non-union hat manufacturer. The manufacturer sued the union under the Sherman Antitrust Act for unlawfully restraining trade. In the 1908 Danbury Hatters' Case the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the union was liable for damages. In the 1930s and 1940s, there were a number of violent incidents during several strikes, mostly involving scab workers brought in as strikebreakers.[28]: 58–61

Beginning in 1892, the industry was revolutionized when the large hat factories began to shift to manufacturing unfinished hat bodies only, and supplying them to smaller hat shops for finishing. While Danbury produced 24% of America's hats in 1904, the city supplied the industry with 75% of its hat bodies.[28]: 57 The turn of the century was the heyday of the hatting industry in Danbury, when it became known as the "Hat City" and the "Hatting Capitol of the World". Its motto was "Danbury Crowns Them All".

Mercury poisoning

editThe use of mercuric nitrate in the felting process poisoned many workers in the hat factories, creating a condition called erethism, also called "mad hatter disease."[30] The condition, known locally as the "Danbury shakes", was characterized by slurred speech, tremors, stumbling, and, in extreme cases, hallucinations.[31][32] The effect of mercury on the workers' health was first noted in the late 19th century. While workers in the Danbury factories lobbied for controls on mercury in the early 20th century, a government study on the health effects of mercury was not conducted until 1937. The State of Connecticut announced a ban on mercury in hatmaking in 1941.[33]

While Danbury hat factories stopped using mercury in the 1940s, the mercury waste has remained in the Still River and adjacent soils, and has been detected at high levels in the 21st century.[27][34][35][better source needed]

Industry decline

editBy the 1920s, the hat industry was in decline. By 1923, only six manufacturers were left in Danbury, which increased the pressure on workers. After World War II, returning GIs went hatless, a trend that accelerated through the 1950s, dooming the city's hat industry.[28]: 64–65 The city's last major hat factory, owned by Stetson, closed in 1964.[36] The last hat was made in Danbury in 1987 when a small factory owned by Stetson closed.[37][38]

Historic pictures

edit-

Main Street looking east from White Street, 1907

-

National Hat Factory, about 1912

-

View of a hat factory, 1911

-

Danbury station, c. 1910

-

Revolutionary Sycamore

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, Danbury has a total area of 44.3 square miles (115 km2), of which 42.1 square miles (109 km2) is land and 2.2 square miles (5.7 km2), or 4.94%, is water. The city is located in the foothills of the Berkshire Mountains on low-lying land just south of Candlewood Lake (the City includes the southern parts of the lake). It developed along the Still River, which flows generally from west to east through the city before joining the Housatonic River. The city's terrain includes rolling hills and not-very-tall mountains to the west and northwest called the Western Highland. Ground elevations in the city range from 378 feet to 1,050 feet above sea level.

A geologic fault known as Cameron's Line runs through Danbury.

Neighboring Connecticut towns

editPollution

editThe hatmaking fur-removal process was based on the use of mercury nitrate. The waste caused serious water pollution as the hat manufacturers dumped it into the Still River throughout the late 19th century and into the 1940s. This toxic product flowed into the Housatonic River and Long Island Sound, affecting water quality and various fish and other organisms.[27][39]

Field studies conducted in the Still River basin in the 21st century have detected the continuing presence of high levels of mercury in the river sediments and nearby soils.[27][34]

Climate

editDanbury has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), with four distinct seasons, resembling Hartford more than coastal Connecticut or New York City. Summers are hot and humid, while winters are cold with significant snowfall. The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 28.0 °F (−2.2 °C) in January to 74.5 °F (23.6 °C) in July; on average, temperatures reaching 90 or 0 °F (32 or −18 °C) occur on 18 and 3.1 days of the year, respectively. The average annual precipitation is approximately 56.04 inches (1,420 mm), which is distributed fairly evenly throughout the year; snow averages 49.3 inches (125 cm) per season, although this total may vary considerably from year to year. Extremes in temperature range from 106 °F (41 °C) on July 22, 1926, and July 15, 1995 (the highest temperature recorded in Connecticut[40]) down to −18 °F (−28 °C) on February 9, 1934.

| Climate data for Danbury, Connecticut (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1937–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

78 (26) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

97 (36) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

100 (38) |

91 (33) |

82 (28) |

80 (27) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 57.9 (14.4) |

58.6 (14.8) |

69.1 (20.6) |

83.3 (28.5) |

90.3 (32.4) |

93.7 (34.3) |

96.0 (35.6) |

93.6 (34.2) |

87.7 (30.9) |

79.2 (26.2) |

69.3 (20.7) |

59.2 (15.1) |

97.7 (36.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.1 (2.3) |

39.8 (4.3) |

47.9 (8.8) |

61.0 (16.1) |

71.8 (22.1) |

80.6 (27.0) |

85.5 (29.7) |

82.2 (27.9) |

75.1 (23.9) |

63.2 (17.3) |

51.1 (10.6) |

40.5 (4.7) |

61.2 (16.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 28.0 (−2.2) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

37.8 (3.2) |

49.7 (9.8) |

60.0 (15.6) |

69.3 (20.7) |

74.4 (23.6) |

72.3 (22.4) |

64.4 (18.0) |

52.7 (11.5) |

41.9 (5.5) |

32.5 (0.3) |

51.1 (10.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 19.9 (−6.7) |

21.1 (−6.1) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

38.5 (3.6) |

48.2 (9.0) |

58.1 (14.5) |

63.4 (17.4) |

61.8 (16.6) |

54.0 (12.2) |

42.2 (5.7) |

32.7 (0.4) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

41.1 (5.0) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 1.3 (−17.1) |

5.2 (−14.9) |

12.0 (−11.1) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

34.3 (1.3) |

44.4 (6.9) |

52.5 (11.4) |

49.8 (9.9) |

38.7 (3.7) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

18.0 (−7.8) |

8.7 (−12.9) |

−1.4 (−18.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −18 (−28) |

−16 (−27) |

−9 (−23) |

14 (−10) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

38 (3) |

37 (3) |

23 (−5) |

16 (−9) |

0 (−18) |

−11 (−24) |

−18 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.74 (95) |

3.28 (83) |

4.43 (113) |

4.17 (106) |

4.23 (107) |

4.83 (123) |

4.98 (126) |

4.88 (124) |

4.89 (124) |

4.97 (126) |

4.02 (102) |

4.65 (118) |

56.04 (1,423) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 15.7 (40) |

11.0 (28) |

10.4 (26) |

1.7 (4.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.9 (4.8) |

8.6 (22) |

49.3 (125) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 7 (18) |

9 (23) |

6 (15) |

1 (2.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (2.5) |

5 (13) |

12 (30) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12.0 | 10.8 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 13.1 | 12.0 | 10.7 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 134.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.0 | 6.0 | 4.7 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 5.5 | 26.6 |

| Source: NOAA[41][42] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1756 | 1,527 | — |

| 1790 | 3,031 | +98.5% |

| 1800 | 3,180 | +4.9% |

| 1810 | 3,606 | +13.4% |

| 1820 | 3,873 | +7.4% |

| 1830 | 4,311 | +11.3% |

| 1840 | 4,504 | +4.5% |

| 1850 | 5,964 | +32.4% |

| 1860 | 7,234 | +21.3% |

| 1870 | 8,753 | +21.0% |

| 1880 | 11,666 | +33.3% |

| 1890 | 19,473 | +66.9% |

| 1900 | 19,474 | +0.0% |

| 1910 | 23,502 | +20.7% |

| 1920 | 22,325 | −5.0% |

| 1930 | 26,955 | +20.7% |

| 1940 | 27,921 | +3.6% |

| 1950 | 30,337 | +8.7% |

| 1960 | 39,382 | +29.8% |

| 1970 | 50,781 | +28.9% |

| 1980 | 60,470 | +19.1% |

| 1990 | 65,585 | +8.5% |

| 2000 | 74,848 | +14.1% |

| 2010 | 80,893 | +8.1% |

| 2020 | 86,518 | +7.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[43] 2018 Estimate[44] Population by Decade 1790–2010[45] State of Connecticut[46] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[47] | ||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[48] | Pop 2010[49] | Pop 2020[50] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 50,945 | 46,309 | 37,963 | 68.06% | 57.25% | 43.88% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 4,743 | 5,030 | 5,630 | 6.34% | 6.22% | 6.51% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 131 | 106 | 70 | 0.18% | 0.13% | 0.08% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 4,068 | 5,399 | 5,339 | 5.44% | 6.67% | 6.17% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 13 | 21 | 25 | 0.02% | 0.03% | 0.03% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 1,096 | 1,845 | 2,980 | 1.46% | 2.28% | 3.44% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 2,061 | 1,998 | 5,821 | 2.75% | 2.47% | 6.73% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 11,791 | 20,185 | 28,690 | 15.75% | 24.95% | 33.16% |

| Total | 74,848 | 80,893 | 86,518 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

It's estimated that the population of Danbury as of 2015 is 84,657.[2] As of the 2010 census, there were 80,893 people and 29,046 households in the city, with 2.73 persons per household. 44.1% of the population spoke a language other than English at home. The population density was 1,921.4 people per square mile. There were 31,154 housing units at an average density of 740.0 per square mile. The racial makeup of the city was 68.2% White, 25.0% Hispanic or Latino (of any race), 7.2% African American, 0.40% Native American, 6.8% Asian, less than 0.10% Pacific Islander, 7.6% from other races, and 4.5% from two or more races. 32% of the population was foreign born. Of particular note is a sizeable population of residents of Portuguese and Brazilian heritage. They are served by locally based Portuguese-language print and broadcast media.

6.7% of the population was under the age of 5, and 21.1% was under the age of 18. 11.1% of the population was 65 years of age or older. 50.9% of the population was female.

The per capita income for the city was $31,411. 11.1% of the population was below the poverty line. The median gross monthly rent was $1,269.

In 2015 the median income for a household in the city was approximately $66,676.[51]

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of October 31, 2023 [52] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Active voters | Inactive voters | Total voters | Percentage | |

| Unaffiliated | 19,671 | 1,287 | 20,958 | 45.53% | |

| Democratic | 14,260 | 787 | 15,047 | 32.69% | |

| Republican | 8,760 | 487 | 9,247 | 20.08% | |

| Minor parties | 731 | 52 | 783 | 1.7% | |

| Total | 43,422 | 2,613 | 46,035 | 100% | |

When ZIP codes were introduced in 1963, the 06810 code was given to all of Danbury; it was shared with a then-still-rural New Fairfield to its north. In 1984, the 06810 Zip Code was cut back to areas of Danbury south of Interstate 84. A new 06811 ZIP code was created for areas north of Interstate 84. New Fairfield received its own code, 06812.

Economy

editIn 2016 Danbury's workforce was approximately 79,400 workers. 12,200 (15.4%) of them worked in goods producing industries. 67,200 (84.6%) of them worked in service providing industries which includes: trade, transportation and utilities (17,300), professional and business services (9,400), leisure and hospitality (7,300), government (10,200) and all other (23,000). In Nov. 2016, the unemployment rate for the Danbury Labor Market Area was 3.0%, compared to 3.7% for the State and 4.6% nationally.[53]

The top employers in the city in 2020 were:[54]

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Western CT Health Network-Danbury | 3,300 |

| 2 | Boehringer Ingelheim | 2,500 |

| 3 | Danbury School Systems | 2,400 |

| 4 | Cartus | 1,300 |

| 5 | IQVIA | 1,040 |

| 6 | Western Connecticut State University | 650 |

| 7 | Praxair | 602 |

| 8 | UTC B.F. Goodrich | 550 |

| 9 | City of Danbury | 548 |

| 10 | Pitney Bowes | 315 |

Government

editThe chief executive officer of Danbury is the Mayor, who serves a two-year term. The current mayor is Roberto L. Alves (D). The Mayor is the presiding officer of the City Council, which consists of 21 members, two from each of the seven city wards, and seven at-large.[55] The City Council enacts ordinances and resolutions by a simple majority vote. If after five days the Mayor does not approve the ordinance (similar to a veto), the City Council may re-vote on it. If it then passes with a two-thirds majority, it becomes effective without the Mayor's approval. The current City Council consists of 14 Republicans and 7 Democrats.[55][56] Danbury has six state representatives as of 2021; Raghib Allie-Brennan D-2, Stephen Harding R-107, Patrick Callahan R-108, David Arconti D-109, Bob Godfrey D-110 and Kenneth Gucker D-138.[57] There is one state senator, Julie Kushner D-24. Danbury is represented in the United States Congress by U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes (D).

Danbury's Fiscal Year 2020–2021 mill rate is 27.60.[58]

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 53.15% 16,318 | 45.50% 13,971 | 1.35% 415 |

| 2020 | 58.93% 18,869 | 39.94% 12,788 | 1.13% 364 |

| 2016 | 55.75% 16,084 | 40.30% 11,626 | 3.95% 1,139 |

| 2012 | 58.45% 15,290 | 40.48% 10,590 | 1.07% 281 |

| 2008 | 59.41% 16,028 | 39.78% 10,732 | 0.81% 219 |

| 2004 | 51.34% 13,477 | 47.24% 12,399 | 1.42% 372 |

| 2000 | 55.13% 12,987 | 39.78% 9,371 | 5.09% 1,199 |

| 1996 | 53.59% 12,102 | 35.27% 7,965 | 11.14% 2,515 |

| 1992 | 38.35% 9,909 | 39.90% 10,310 | 21.75% 5,621 |

| 1988 | 42.10% 10,071 | 57.23% 13,690 | 0.66% 158 |

| 1984 | 35.38% 8,922 | 64.01% 16,143 | 0.61% 154 |

| 1980 | 40.04% 9,374 | 48.30% 11,308 | 11.67% 2,732 |

| 1976 | 46.50% 10,379 | 52.76% 11,777 | 0.74% 166 |

| 1972 | 37.51% 8,186 | 60.81% 13,271 | 1.69% 368 |

| 1968 | 48.12% 9,602 | 44.85% 8,948 | 7.03% 1,403 |

| 1964 | 69.30% 12,932 | 30.70% 5,728 | 0.00% 0 |

| 1960 | 54.53% 10,363 | 45.47% 8,640 | 0.00% 0 |

| 1956 | 34.11% 5,816 | 65.89% 11,233 | 0.00% 0 |

Infrastructure

editEducation

editPublic schools

editDanbury Public Schools operates most public schools, with Danbury High School belonging to the district. The other public high school, Henry Abbott Technical High School, is within the Connecticut Technical High School System. Each high school is grades 9 through 12. An alternative school by the name of Alternative Center for Excellence is housed off-campus, and its graduates receive Danbury High School diplomas upon completion of their studies.[61] Danbury also has 3 public middle schools for grades 6 through 8: Broadview Middle School, Rogers Park Middle School and Westside Middle School Academy.[62] There are 13 elementary schools in Danbury. These schools are Academy for International Studies Magnet School (K–5), Ellsworth Avenue (K–5), Great Plain (K–5), Hayestown (K–5), King Street Primary (K–3) and King Street Intermediate (4–5), Mill Ridge Primary (K–3), Morris Street (K–5), Park Avenue (K–5), Pembroke (K–5), Shelter Rock (K–5), South Street (K–5) and Stadley Rough (K–5).[63]

Parochial schools

editRoman Catholic schools in Danbury reside within the administration of the Diocese of Bridgeport and include:

- 1 high school: Immaculate High School (9–12)

- 3 elementary schools: St Peter-Sacred Heart School (Pre-K–8),[64] St. Gregory the Great School (Pre-K–8),[65] and St. Joseph School (Pre-K–8)

Other parochial schools in Danbury are:

Private schools

edit- Hudson Country Montessori School[68]

- New England Country Day School[69]

- Wooster School

Post-secondary schools

editDanbury is home to Western Connecticut State University and a campus of Naugatuck Valley Community College.[70]

Danbury Federal Correctional Institution

editDanbury is the site of a low-security men's and women's prison, the Danbury Federal Correctional Institution, located near the border with New Fairfield.[71] Built in the 1940s to house men, the facility was converted to a women's prison in 1994 to address a shortage of beds for low-security female inmates in other facilities. However, overcrowding at federal facilities for low-security males prompted a reconversion to a male prison, beginning in 2013, and relocation of the female inmates from the low-security Pembroke Road facility to other locations.[72] As of 2016, an adjacent satellite camp houses up to 193 women.[71][73] A new $25 million women's facility was completed and began accepting female inmates in December 2016.[74]

Libraries

editThe Danbury Public Library was established in 1869.[75]

The Long Ridge Library is a small library occupying an old schoolhouse on Long Ridge Road in Danbury. It was founded in 1916.[76]

Places of worship

editDanbury is home to numerous churches, three synagogues, two mosques, and a Hindu temple.

Mass media

editDanbury is in the New York City TV market and receives its TV stations. Some TV stations in the Hartford-New Haven are also available to Danbury viewers.

- The News-Times – a daily newspaper owned by Hearst Communications.

- Tribuna Newspaper – a biweekly, bilingual (Portuguese/English) news publication.

- HamletHub Danbury – a local news publication.

- WFAR-FM, 93.3 MHz, low-power – religious (Christian) and ethnic/Portuguese-language programming.

- WLAD-AM, 800 kHz, 1000 watts (daytime), 287 watts (nighttime) – news/talk format, owned by the Berkshire Broadcasting Corporation.

- WDAQ-FM 98.3 MHz, 1300 watts – hot adult contemporary format, owned by the Berkshire Broadcasting Corporation.

- WDAQ-HD2 FM, 103.7 MHz – alternative rock format, owned by the Berkshire Broadcasting Corporation.[77]

- WDAQ-HD3 FM, 107.3 MHz – new country music, owned by the Berkshire Broadcasting Corporation.[78]

- WDAQ-HD4 FM, 94.5 MHz – "The Hawk" – classic rock format, owned by the Berkshire Broadcasting Corporation.[79]

- WAXB, 850 kHz AM / 94.5 MHz FM, 2500 watts (daytime only) – Spanish-language adult hits, owned by the Berkshire Broadcasting Corporation.

- WXCI-FM, 91.7 MHz, 3000 watts – non-profit, college radio station, owned by Western Connecticut State University and operated by past and present students

- WRKI-FM, 95.1 MHz, 50000 watts – classic rock music, owned by Townsquare Media; debuted on December 24, 1976.

- WDBY-FM, 105.5 MHz ("Kicks 105.5") – contemporary country music, owned by Townsquare Media.

- WINE-AM, 940 kHz – Portuguese, owned by International Church of the Grace of God, Inc.

Public utilities

editThe Public Utilities Division operates and maintains the City of Danbury's Water Division, water utility infrastructure, sanitary sewer infrastructure, which includes several large water supply dams, a closed landfill, landfill gas collection system, and administer programs for recycling and disposal of solid waste.[80] The Division oversees a Water Pollution Control Plant, operated by Veolia Water North America, and a public yard waste management processing center, located on Plumtrees Road, in accordance with an agreement between the City of Danbury and Total Landscaping and Tree Service. The sewer fund makes up 80 percent of Danbury's 2019–2020 Adopted Capital Projects Budget, accounting for $103 million of the $127 million budget to maintain the plant.[81]

In October 2020, the city renamed its water pollution control plant the John Oliver Memorial Sewer Plant after John Oliver, the host of the late-night comedy program Last Week Tonight with John Oliver jokingly insulted the city. Oliver attended the unveiling ceremony in person as a condition of Mayor Boughton.[82][83]

Transportation

editHighways

editInterstate 84 and U.S. Route 7 are the main highways in the city. I-84 runs west to east from the lower Hudson Valley region of New York to Waterbury and Hartford. US 7 runs south to north from Norwalk (connecting to I-95) to the Litchfield Hills region. The two highways overlap in the downtown area. The principal surface roads through the city are Lake Avenue, West Street, White Street, and Federal Road. Other secondary state highways are U.S. Route 6 in the western part of the city, Newtown Road, which connects to US 6 east of the city, Route 53 (Main Street and South Street), Route 37 (North Street, Padaranam Road, and Pembroke Road), and Route 39 (Clapboard Ridge Road and Ball Pond Road). Danbury has 242 miles of streets.[84]

Buses

editLocal bus service is provided by Housatonic Area Regional Transit (HART), and connects the entire Greater Danbury region as well as various train stations along the Harlem Line in Putnam County and Westchester County. A shuttle also operates between Downtown Danbury and Norwalk.

Railroad

editDanbury is the terminus of the Danbury branch line of the MTA Metro-North Railroad which begins in Norwalk. The Danbury Branch provides commuter rail service from Danbury, to South Norwalk, Stamford, and Grand Central Terminal in New York City. The line was first built by the Danbury and Norwalk Railroad which was later bought by the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad Company. Danbury was an important junction between the Danbury Branch and the Maybrook Line. The Maybrook line was the New Haven's main freight line which terminated in Maybrook, New York, where the New Haven exchanged traffic with other railroads. After the ill-fated Penn Central took over the New Haven, the Maybrook line was shut down when a fire on the Poughkeepsie Bridge made the line unusable. Today, the historic station is part of the Danbury Railway Museum. The Providence and Worcester Railroad, along with the Housatonic Railroad provide local rail freight service in Danbury.

Frequent direct rail access to New York City is also available from Brewster station along Metro-North's Harlem Line. The station is located just over the New York state line, roughly 8 miles from downtown. Plans are also being made to connect Danbury station to the Harlem Line, utilizing existing Maybrook Line track which is owned by the MTA. This plan has been dubbed the "Fast track to NYC", as it will provide more frequent access between Danbury and Grand Central Terminal. In June 2022, a $2 million federal grant was approved to study the environmental impacts of the project.[85]

Airports

editDanbury is within reasonable distance of 11 airports: four general aviation, two regional, five international. The city is also the location of Danbury Municipal Airport (DXR).

| General aviation airports | Distance from Downtown/Location |

|---|---|

| Danbury Municipal Airport | 2 miles southwest in Danbury, Connecticut |

| Waterbury–Oxford Airport | 18 miles northeast in Oxford, Connecticut |

| Sikorsky Memorial Airport | 23 miles southeast in Stratford, Connecticut |

| Teterboro Airport | 49 miles southwest in Teterboro, New Jersey |

| Regional airports | Distance form Downtown/Location |

|---|---|

| Westchester County Airport | 26 miles southwest in Westchester County, New York |

| Tweed New Haven Airport | 30 miles southeast in East Haven, Connecticut |

| Stewart Airport | 34 miles west in Newburgh, New York |

| International airports | Distance from Downtown/Location |

|---|---|

| LaGuardia Airport | 48 miles southwest in Queens, New York |

| John F. Kennedy International Airport | 54 miles south in Queens, NY |

| Bradley International Airport | 55 miles northeast in Windsor Locks, Connecticut |

| Newark Liberty International Airport | 61 miles southwest in Newark, New Jersey |

Sites of interest

editHiking trails

edit- Bear Mountain Reservation[86]

- The Old Quarry Nature Center has two short educational trails on 39 acres (16 ha)[87]

- Tarrywile Mansion and Park[88] has 21 miles (34 km) of trails and several ponds on 722 acres (292 ha), as well as a Victorian mansion and gardens. The Ives Trail runs through the park.

- The Ives Trail is a 20-mile stretch of trail that runs from Bennett's Pond in Ridgefield through Danbury to Redding. The Charles Ives House and Hearthstone Castle are located along this trail.

Parks

edit- Bear Mountain Park

- Blind Brook Park

- Candlewood Town Park

- Danbury Dog Park at Margerie Lake Reservoir

- Danbury Dog Park at Miry Brook

- Elmwood Park

- Farrington Woods

- Hatters Park

- Highland Playground

- Joseph Sauer Memorial Park

- Kennedy Park

- Lake Kenosia Park

- Lions Club Children's Park on Rowan Street

- Memorial Park

- Old Quarry Nature Center

- Richter Park

- Rogers Park

- Rogers Park Playground

- Stephen A. Kaplanis Field

- Still River Greenway

- Tarrywile Park

- Tom West Park[89]

Museums

editOther

edit- The Connecticut 9/11 Memorial by sculptor Henry Richardson is located in Danbury in Elmwood Park.[90]

- The Danbury Fair Mall was built on the old fairgrounds in 1986.

- Danbury is also home to an Army Reserve Special Operations unit, the 411th Civil Affairs Battalion.

- Danbury Hospital is a 456-bed[91] hospital, serving patients in Fairfield County, Connecticut and Putnam County, New York.[92] The hospital is the home of the new Praxair Regional Heart and Vascular center,[93] providing state of the art cardiovascular care to this growing region including open heart surgery and coronary angioplasty.

- Richter Park Golf Course is Danbury's municipal golf course[94] and hosts numerous tournaments such as the annual Danbury Amateur and American Junior Golf Association majors. It has won a variety of awards, including being a "Top 10 Connecticut Course" and the "#2 Best Public Course in the NY Metropolitan Area".[95]

- The Summit at Danbury is one of the largest office complexes in Connecticut

- Danbury Ice Arena

- The John Oliver Memorial Sewer Plant

National Register of Historic Places

edit| Name | Location | Date added to NRHP |

|---|---|---|

| Ball and Roller Bearing Company | 20–22 Maple Ave. | September 25, 1989 |

| Charles Ives House | 7 Mountainville Ave. | May 26, 1976 |

| Hearthstone | 18 Brushy Hill Rd. | December 31, 1987 |

| John Rider House | 43 Main St. | added December 23, 1977 |

| Locust Avenue School | Locust Ave. | June 30, 1985 |

| Main Street Historic District | Boughton, Elm, Ives, Keeler, Main, West and White Sts. | December 29, 1983 |

| Meeker's Hardware | 86–90 White St. | July 9, 1983 |

| Octagon House | 21 Spring St. | June 7, 1973 |

| P. Robinson Fur Cutting Company | Oil Mill Rd. | December 30, 1982 |

| Tarrywile | Southern Blvd. & Mountain Rd. | February 6, 1988 |

| Union Station (Danbury Railway Museum) | White St. and Patriot Dr. | October 25, 1986 |

| Richter House (Richter Memorial Park) | 100 Aunt Hack Road | September 17, 2010 |

Sports

editIce hockey

editThe United Hockey League (UHL) expanded to Danbury in 2004. The Danbury Trashers played their first season at the Danbury Ice Arena in October 2004. Among those on the roster included Brent Gretzky (brother of hockey legend Wayne Gretzky) and Scott Stirling (son of former New York Islanders coach Steve Stirling). Scott's older brother, Todd, coached the Trashers in the 2004–2005 season. The team folded in 2006 after its owner, coach and management were charged (and later convicted) of several charges of wire fraud and racketeering.[96][97][98]

On December 27, 2009, Danbury was named the first city to officially have a team in the newly formed Federal Hockey League (FHL). The team was named the Danbury Whalers, bringing back the name "Whalers" to Connecticut for the first time since 1997 when the Hartford Whalers of the WHA/NHL moved to North Carolina and became the Carolina Hurricanes. At the end of the 2014–2015 season, the Danbury Ice Arena evicted the Danbury Whalers. However, a new FHL Danbury team called the Danbury Titans was approved for the 2015–2016 season, owned by local car dealership owner Bruce Bennett. The Titans folded after two seasons.[99]

The Danbury Ice Arena was sold and put under new management in 2019. The arena then added a third FPHL franchise called the Danbury Hat Tricks, a Tier III junior team called the Danbury Colonials, and the relocation of the Premier Hockey Federation's Connecticut Whale. In 2020, the arena added a Tier II junior team called the Danbury Jr. Hat Tricks and the Tier III team also rebranded to the same name.

Other sports

editThe Danbury Westerners, a member of the New England Collegiate Baseball League, play their home games at Rogers Park in Danbury.

Danbury-based amateur soccer team Villanovence FC play in the United Premier Soccer League.

Danbury High School carries a strong athletic tradition in wrestling, boys and girls track and field, boys cross country, baseball, tennis, basketball, and football. The wrestling, boys cross country, and boys track teams have all numerous state titles and New England championships. All three programs are considered to be nationally ranked annually.

Western Connecticut State University is a member of the NCAA Division III, the Eastern College Athletic Conference, and the Little East Conference. The university fields teams in baseball, basketball, lacrosse, football, soccer, softball, swimming, tennis, and volleyball. WestConn also fields several nationally competitive club sports on campus including Men's Rugby, Women's Rugby, Dance Team, Cheerleading, and Men's Hockey.

The Danbury Hatters Cricket Club formed in 2001 and has been playing cricket in Southern Connecticut along with other cities such as Norwalk, Stamford, Bridgeport, New Haven, Waterbury and West Haven. Their home ground is Broadview Middle School.[100]

The Western Connecticut Militia is a semi-professional football team that played in the New England Football League from 2011 to 2016, winning the league championship the last year. The team played its home games in Danbury during that period. After taking 2017 off, the team joined Major League Football for the 2018 season, playing its home games in New Fairfield, CT.[101]

Notable people

edit- Alex Pereira (brazilian, 07/07/1987), also known as "Alex Poatan", professional wrestler | UFC World Champion, Champion UFC 295, UFC 300, UFC 303 and UFC 307

- Glover Teixeira, Professional MMA Fighter in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) and former champion of the Light heavyweight (MMA) division

- Renata Adler, author, journalist and film critic

- Willard H. Allen (1893–1957), New Jersey secretary of agriculture

- Marian Anderson (1897–1993), singer

- Sylvia Sydney (1910–1999), actress[102]

- James Montgomery Bailey, 19th century Danbury News editor

- Matt Barnes, professional baseball player

- Zadoc Benedict, the first hat maker of Danbury

- Jonathan Brandis (1976–2003), actor

- Peter Buck (1930–2021), co-founder, Subway sandwich restaurants[103]

- Austin Calitro, professional football player

- Ray Cappo, singer

- Neil Cavuto, television anchor

- Frank Conniff (1914–1971), 1956 Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist

- Mackenzie Fierceton, activist

- Ken Green, professional golfer

- Lee Hartell, Medal of Honor recipient

- Charles Ives (1874–1954), composer[104]

- Joe Lahoud, professional baseball player

- Steven Kaplan, American economist and professor

- Carole King, singer-songwriter[105]

- Rose Wilder Lane, author, writer, daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder

- Jimmy Monaghan, Irish musician and former boxer

- Jerry Nadeau, professional auto racing driver

- Steven Novella, neurologist and noted skeptic

- Laura Nyro (1947–1997), musician, songwriter, bandleader, singer

- Elizabeth Peyton, painter

- Chet Powers a.k.a. Dino Valenti (1937–1994), musician and songwriter

- George Radachowsky, professional football player

- William R. Ratchford, three term U.S. Congressman

- Allen Ritter, music producer

- Delvin Rodríguez, professional boxer

- Neil Rudenstine, past president of Harvard University

- James A. Ryan, U.S. Army brigadier general[106]

- Chauncey Foster Ryder, Postimpressionist painter

- Trevor Siemian, professional football player

- Christian Siriano, fashion designer

- Ian Smith, panelist on VH1's Celebrity Fit Club

- Lee Smith, Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame, Relief Pitcher [107]

- Ronnie Spector, singer[108]

- Roy M. Terry, Chief of Chaplains of the U.S. Air Force

- John Toland (1912–2004), 1971 Pulitzer Prize-winning historian[109]

- TJR (birth name Thomas Joseph Rozdilsky), musician

- John Hubbard Tweedy, U.S. Congressional Delegate from the Wisconsin Territory[110]

- Samuel Tweedy (1776–1868), U.S. Representative from Connecticut

- Jenna von Oÿ, actress

- William A. Whittlesey, former U.S. Congressman

- Zalmon Wildman (1775–1835), U.S. Representative from Connecticut

Cultural references

edit- Danbury's sewage plant has been named the "John Oliver Memorial Sewer Plant" in honor of comedian John Oliver after a lighthearted social media exchange between Oliver and mayor Mark Boughton following Oliver's satirical criticism of Danbury on Last Week Tonight with John Oliver in August 2020. Oliver donated $55,000 to local charities in exchange for the renaming.[111] In October 2020, Oliver visited Danbury for the official unveiling of the renamed plant.

- In Robert Lawson's children's novel Rabbit Hill, the story's anthropomorphic rabbit characters preserve by oral tradition the memory of Danbury being burned by the British during the American War of Independence and later of the town's young men going off to fight in the American Civil War and many of them not coming back.[112]

- The Netflix series Orange Is the New Black was based off of the Federal Women's Prison located in Danbury.

Sister cities

editSee also

edit- CityCenter Danbury, a redevelopment project in the city's downtown

- Greater Danbury, the metropolitan area centered on the city

References

edit- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "QuickFacts Danbury city, Connecticut". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ "Race, Hispanic or Latino, Age, and Housing Occupancy: 2020 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File (QT-PL), Danbury city, Connecticut". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Charles, Eleanor. "If You're Thinking of Living In / Danbury, Conn.; Bustling, but Studded With Lakes, Ponds", The New York Times, March 14, 1999. Accessed September 18, 2024.

- ^ Eno, Joel N. (1903). "The Nomenclature of Connecticut Towns". The Connecticut Magazine. Vol. 8, no. 11. p. 331. OCLC 1015837896. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ^ "A Student's Guide to Danbury, Connecticut". November 4, 2009. Archived from the original on December 15, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ Paula D. Hunt, "Sybil Ludington, the Female Paul Revere: The Making of a Revolutionary War Heroine." New England Quarterly (2015) 88#2, pp. 187–222, quote p 187 online Archived April 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tucker, Abigail (March 2022). "Did the Midnight Ride of Sibyl Ludington Ever Happen?". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Eschner, Sybil (April 26, 2017). "Was There Really a Teenage, Female Paul Revere?". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Sybil Ludington: a Revolutionary Hero Archived December 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, traverseforwomen.com; accessed February 23, 2015.

- ^ Ravo, Nick, "Country Fair Becomes Land of the Lava Lamp Archived July 29, 2018, at the Wayback Machine", The New York Times, September 4, 1987

- ^ Danbury Museum and Historical Society. "Timeline" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ Danbury Museum and Historical Society. "Kohanza Disaster" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ "Albert Afraid-of-Hawk". Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Hassan, Diane; Cedrone, Sarajane (September 20, 2015). "Rediscovering Albert Afraid-of-Hawk". Connecticut Explored. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ D'Emilio, John (2003). Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0684827808.

- ^ Kosek, Joseph Kip (2009). Acts of Conscience: Christian Nonviolence and Modern American Democracy. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231144186.

- ^ Bennett, Scott H. (2003). Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915–1963. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815630034.

- ^ Hanrahan, Ryan. "Way Too Much Weather". ryanhanrahan.com. Ryan Hanrahan. Archived from the original on November 24, 2016. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- ^ Devlin, William; Janick, Herbert (April 2013). Danbury's third Century: From Urban Status to Tri-Centennial. Danbury, CT: Western Connecticut State University. pp. 229–241. ISBN 978-0-9889243-1-4.

- ^ Pirro, John (February 12, 2012). "Pardue brothers bombed Danbury 42 years ago today". newstimes. Hearst Media Services Connecticut. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Richard Eisenberg and Debra Wishik Englander (August 1, 1988). "The Best Places to Live in America in our second annual rating of 300 U.S. areas, the Northeast and California score best – though a New Jersey city is last". Money Magazine. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Somma, Ann Marie (August 16, 2014). "Where are they now? The Danbury 11 not forgotten". newstimes. Hearst Media Services Connecticut, LLC. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Perrefort, Dirk (March 9, 2011). "City officials reach $400,000 settlement with Danbury 11 day laborers". newstimes. Hearst Media Services Connecticut, LLC. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Robinson, Alfons o. "The public deserves to know the truth about the Danbury 11 case". Hearst CT News Blogs. Hearst Communications, Inc. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Pirro, John (February 1, 2011). "The rise—and fall—of hatting in Danbury". Danbury News-Times. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Varekamp, Johan. "'Mad Hatters' Long Gone, But The Mercury Lingers On". Daily University Science News. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Devlin, William E. (1984). We Crown Them All (First ed.). Windsor Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-89781-092-9.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Inventory--Nomination Form: P. Robinson Fur Cutting Company". October 15, 1982. Submitted to the National Park Service by the Connecticut Historical Commission. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Buckell, M; Hunter, D; Milton, R; Perry, KM (February 1993) [1946]. "Chronic mercury poisoning". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 50 (2): 97–106. doi:10.1136/oem.50.2.97-a. PMC 1061245. PMID 8435354.

- ^ "Mercury Workshop" (PDF). Ohio Indoor Air Quality Coalition. 2008. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

In the late 1800s hat makers, or hatters, used to use mercury nitrate when working with beaver fur to make felt. Over time, the hatters started exhibiting apparent changes in personality and also experienced tremors or shaking. Mercury poisoning attacks the nervous system, causing drooling, hair loss, uncontrollable muscle twitching, a lurching gait, and difficulties in talking and thinking clearly. Stumbling about in a confused state with slurred speech and trembling hands, affected hatters were sometimes mistaken for drunks. The ailment became known as 'The Danbury Shakes' in the community of Danbury where hat making was a major industry. In very severe cases, they experienced hallucinations. The term 'mad as a hatter' may be a product of mercury toxicity.

- ^ McDowell, Lee (2017). Mineral Nutrition History: The Early Years. Design Pub. p. 658. ISBN 978-1-5069-0459-7. Archived from the original on September 22, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Wajda, Shirley T. (December 12, 2019). "Ending the Danbury Shakes: A Story of Workers' Rights and Corporate Responsibility". Connecticut History. Archived from the original on October 22, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Bronsther, Rachel; Welsh, Patrick. Mercury in Soils and Sediments (Report). Wesleyan University. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ Lerman-Sinkoff, Sarah Tziporah (April 2014). Transport and Fate of Historic Mercury Pollution from Danbury, CT through the Still and Housatonic Rivers (BA thesis). Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University. doi:10.14418/wes01.1.1052. Archived from the original on September 8, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Devlin, William E.; Janick, Herbert F. (April 2013). Danbury's Third Century: From Urban Status to Tri-Centennial (First ed.). Danbury, CT: Western Connecticut State University. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-0-9889243-1-4.

- ^ Serra, Janet (June 2, 2011). "Magnificent Millinery: Three Centuries of Women's Hats in Danbury CT". Connecticut Travel. Western Connecticut Convention and Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ Libov, Charlotte (March 20, 1988). "Mecca for the Bargain Hunter". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Varekamp, JC; Buchholtz ten Brink, MR; Mecray, EL; Kreulen, B (Summer 2000). "Mercury in Long Island Sound Sediments". Journal of Coastal Research. 16 (3): 613–626. JSTOR 4300074.

- ^ "Connecticut". Netstate, LLC. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Danbury, CT". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Bethel population; Bridgewater population; Brookfield population; Danbury population; New Fairfield population; New Milford population; Newtown population; Redding population; Ridgefield population; Sherman population Archived June 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Hvceo.org. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ Office of the Secretary of the State Archived September 13, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Sots.state.ct.us. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Danbury city, Connecticut". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Danbury city, Connecticut". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Danbury city, Connecticut". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ St. Hilaire, David W. "Comprehensive Financial Annual Report" (PDF). City of Danbury. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Registration and Party Enrollment Statistics" (PDF). Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ St. Hilaire, David. "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). City of Danbury, CT. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ Danbury Dept. of Finance. "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, City o Danbury" (PDF). City of Danbury, CT. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ a b "City of Danbury, Connecticut – City Council". City of Danbury, Connecticut. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Perkins, Julia (November 3, 2021). "Who was elected in Danbury? Here are the results". NewsTimes. Hearst CT Media. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ "State Legislators". CBIA. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ "Mill Rates". Office of Policy and Management. Archived from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ "General Elections Statement of Vote 1922". Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ "Election Night Reporting". CT Secretary of State. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ "Academic s". Alternative Center for Excellence. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ "Danbury Public Schools". Archived from the original on June 23, 2005. Retrieved June 27, 2005.

- ^ "Danbury Public Schools". Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ "Saint Peter School". Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ "St. Gregory the Great School - Danbury, Connecticut .:. Welcome". Archived from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "Colonial Hills Christian Academy". Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "Immanuel Lutheran School, Danbury, CT". Archived from the original on July 3, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "Hudson Montessori School". Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ "New England Country Day School Profile - Danbury, Connecticut (CT)". Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "NVCC Danbury Campus". NVCC. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ a b "FCI Danbury". Federal Bureau of Prisons. Archived from the original on September 3, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Ryan, Maggie (July 17, 2013). "FCI Danbury Prison Being Converted to House Males". Correctional News. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ^ Freedman, Dan. "Women's prison construction to start this summer". Connecticut Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Ryser, Bob (December 2, 2016). "Enhanced FCI set to reopen to women". The News-Times.

- ^ "Our History". Friends of the Danbury Library. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ "Danbury's Long Ridge Library Embraces Past, Moves Toward Future". Danbury Daily Voice. February 20, 2013. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ Perrefort, Dirk (August 11, 2015). "Danbury gets a new alternative rock station". newstimes. The News-Times. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Venta, Lance (July 5, 2016). "107.3 The Bull Launches In Danbury". radioINSIGHT. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ Venta, Lance (February 26, 2020). "94.5 The Hawk Flies Into Danbury Classic Rock Duel". Radio Insight. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ "Public Utilities". Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "City of Danbury 2019-2020 Adopted Budget Book" (PDF). Danbury-CT. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Danbury Renames Sewer Plant for Comedian John Oliver". NBC Connecticut. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "City of Danbury Won't Waste John Oliver's Donation, on One Condition". NBC Connecticut. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ St. Hilaire, David W. "Comprehensive Financial Annual Report" (PDF). City of Danbury. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ https://www.masstransitmag.com/rail/news/21269671/ct-danburys-long-shot-fast-track-to-nyc-now-more-of-a-reality-with-hope-of-2m-federal-grant Archived December 9, 2022, at the Wayback Machine Mass Transit CT: Danbury's 'long shot' fast track to NYC now 'more of a reality' with hope of $2M federal grant

- ^ "Bear Mt. Reservation Danbury, CT". BerkshireHiking.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "Old Quarry Nature Center, 5 Maple La., Danbury, CT 06810". Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "Tarrywile Park and Mansion, Danbury, CT: Hiking, Weddings, and Events". Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "Parks". City of Danbury. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Pelland, Dave. "9/11 Memorial, Danbury". CTMonuments.net. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ "About Danbury Hospital". Danbury Hospital. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ 2006 Book of Business Lists, Facts and People, published by Westfair Communications Inc. of White Plains, N.Y., in conjunction with its Fairfield County Business Journal, page 57

- ^ Danbury Hospital, Western Connecticut Health Network Archived February 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Danhosp.org. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ Richter Park Golf Course - Danbury, CT Archived July 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Richterpark.com. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ Richter Park Golf Course - Course Stats Archived August 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Richterpark.com. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ Ali, Karen (June 10, 2006). "29 people, 7 firms charged in probe". News-Times. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ "Former Controller of Danbury Trash Companies is Sentenced". United States Attorney's Office District of Connecticut. August 11, 2009. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ "Trashers coach gets probation in trash probe". Boston Herald. Associated Press. October 21, 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Lacey, Ryan (August 3, 2017). "Titans throw in the towel". Hearst Media Services CT. LLC. The News-Times.

- ^ "Danbury Cricket Club". CricClubs.com. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Militia Join the MLF!". Western Connecticut Militia. www.HomeTeamsONLINE.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ^ Steinberg, Alyssa Gallin (December 31, 1999). "Sylvia Sidney". The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. Jewish Women's Archive. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Peter Buck". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Dixon, Ken, "Music Hall of Fame proposed for state", article in Connecticut Post in Bridgeport, Connecticut, April 26, 2007 ("Charles Ives (1874–1954) of Danbury")

- ^ Gurock, Jeffrey S. (2021). Lake Waubeeka: A Community History. The History Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1467149464.

- ^ Marquis, Albert Nelson, ed. (1919). Who's Who In America. Vol. X. Chicago, IL: A. N. Marquis & Company. pp. 2355–2356 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gregory, Richard (June 30, 2016). "Pitching great Lee Smith shares words of wisdom with local ballplayers". newstimes.com. The News-Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Hardaway, Liz (January 13, 2022). "Ronnie Spector, lead of The Ronnettes, Danbury resident dies at 78". News Times. Hearst Connecticut Media. Archived from the original on January 13, 2022. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ Saxton, B. (January 5, 2004). "Renowned 'Rising Sun' author Toland dies in Danbury". The News-Times. Danbury, Connecticut. Archived from the original on July 23, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Index to Politicians: Tutton to Tylee Archived July 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. The Political Graveyard. Retrieved on July 15, 2013.

- ^ McCarthy, Tyler (October 11, 2020). "Danbury, Connecticut officially naming sewage plant after John Oliver following feud". foxbusiness.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ CARY, BILL. "1930s Connecticut Mansion That Was Home to Children's Book Illustrator Robert Lawson". www.mansionglobal.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2021.