Downfall (German: Der Untergang) is a 2004 historical war drama film written and produced by Bernd Eichinger and directed by Oliver Hirschbiegel. It is set during the Battle of Berlin in World War II, when Nazi Germany is on the verge of total defeat, and depicts the final days of Adolf Hitler (portrayed by Bruno Ganz). The cast includes Alexandra Maria Lara, Corinna Harfouch, Ulrich Matthes, Juliane Köhler, Heino Ferch, Christian Berkel, Alexander Held, Matthias Habich, and Thomas Kretschmann. The film is a German-Austrian-Italian co-production.

| Downfall | |

|---|---|

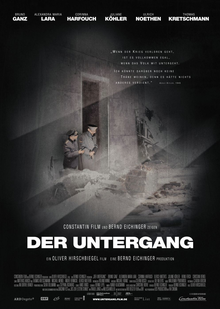

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Oliver Hirschbiegel |

| Screenplay by | Bernd Eichinger |

| Based on | |

| Produced by | Bernd Eichinger |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Rainer Klausmann[1] |

| Edited by | Hans Funck[1] |

| Music by | Stephan Zacharias[1] |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Constantin Film (Germany and Austria) Newmarket Films (USA and United Kingdom) 01 Distribution (Italy) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 155 minutes[2] |

| Countries | Germany United Kingdom Italy Austria[3] |

| Languages | German Italian[2] |

| Budget | €13.5 million[4] (approx. US$16 million) |

| Box office | $92.2 million[5] |

Principal photography took place from September to November 2003, on location in Berlin, Munich, and Saint Petersburg, Russia. As the film is set in and around the Führerbunker, Hirschbiegel used eyewitness accounts, survivors' memoirs, and other historical sources during production to reconstruct the look and atmosphere of 1940s Berlin. The screenplay was based on the books Inside Hitler's Bunker by historian Joachim Fest and Until the Final Hour by Traudl Junge, one of Hitler's secretaries, among other accounts of the period.

The film premiered at the Toronto Film Festival on 14 September 2004. It was controversial with audiences for showing a human side of Hitler, and for its portrayal of members of the Third Reich. It later received a wide theatrical release in Germany under its production company Constantin Film. The film grossed over $92 million. Critics gave favourable reviews, particularly for Ganz's performance as Adolf Hitler and Eichinger's screenplay. It was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 77th Academy Awards.

Plot

editIn 1942, Adolf Hitler invites several young women to interview for the position of personal secretary at the Wolf's Lair on the Eastern Front. Traudl Junge is overjoyed when he chooses her.

In April 1945, the Red Army has pushed Germany's forces back in the ensuing Battle of Berlin. On Hitler's 56th birthday, the shelling of Berlin's city centre starts. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler tries to persuade Hitler to leave Berlin, but Hitler refuses. Himmler leaves to negotiate with the Allies secretly. Later, SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein, Himmler's liaison officer at Hitler's headquarters, attempts to persuade Hitler to flee, but Hitler insists that he will win or die in Berlin. SS doctor Obersturmbannführer Ernst-Günther Schenck is ordered to leave Berlin in Operation Clausewitz but persuades an SS general to let him stay in Berlin. In the streets, Hitler Youth Peter Kranz's father approaches his son's unit and tries to persuade him to leave. Peter, who destroyed two enemy tanks, denounces his father.

At a meeting in the Führerbunker, Hitler forbids the overwhelmed 9th Army to retreat, instead ordering Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner's units alongside Lieutenant General Walther Wenck's 12th Army to mount a counter-attack. The generals find the orders impossible and irrational. Above ground, Hitler awards Peter the Iron Cross, hailing him as braver than his generals. In his office, Hitler talks to armaments minister Albert Speer about his scorched earth policy. Speer is concerned about the destruction of Germany's infrastructure, but Hitler believes the German people are weak and deserve death. Hitler's companion Eva Braun holds a party in the Reich Chancellery, which is interrupted by artillery fire. Her brother-in-law Fegelein tries to persuade Eva to leave Berlin with Hitler, but she refuses.

On the frontline, General Helmuth Weidling is informed he will be executed for allegedly ordering a retreat. Weidling comes to the Führerbunker to clear himself of the charges. His action impresses Hitler, who promotes him to oversee all of Berlin's defences. At another meeting, Hitler learns that Steiner did not attack because his unit lacked sufficient force. Hitler becomes enraged at this and launches into a furious tirade, claiming that everyone has failed him and denouncing his generals as cowards and traitors. He acknowledges that the war is lost but says that he would rather commit suicide than leave Berlin.

SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke asks Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels to stop sending inexperienced soldiers to the battlefront as they are easy prey for the Red Army. Goebbels refuses, claiming that the German people deserve their fate for voting the Nazis into power. Schenck witnesses old men being executed by the Feldgendarmerie for refusing to fight. Hitler receives a message from Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, requesting state leadership for himself. In response, Hitler declares Göring as committing a coup d'etat, ordering his dismissal and arrest. Speer makes a final visit to the Führerbunker and admits that he has defied orders to destroy Germany's infrastructure. Hitler, however, does not punish Speer, and lets him leave Berlin. Peter returns to find his unit dead and runs back home. Hitler continues to imagine ways for Germany to turn the tide. At dinner, Hitler learns of Himmler's secret negotiations with the Allies, sending him into another rage, and he orders Himmler's execution. He discovers that Fegelein has deserted his post and has him executed despite Eva's pleas. SS physician Obergruppenführer Ernst-Robert Grawitz asks Hitler's permission to evacuate for fear of Allied reprisal. Hitler refuses, leading Grawitz to kill his family and himself using grenades.

The Red Army continues advancing as Berlin's supplies run low and German morale plummets. Hitler hopes that even without Steiner, Wenck's 12th Army will save Berlin. After midnight, Hitler dictates his last will and testament to Junge before marrying Eva. The following morning, Hitler learns that the 12th Army is unable to save Berlin. Refusing surrender, Hitler plans his death. He administers poison to his dog Blondi, bids farewell to the bunker staff, and commits suicide with Eva. They are cremated with petrol in a ditch in the Chancellery garden.

Goebbels assumes the Chancellorship but immediately decides to commit suicide after General Hans Krebs fails to negotiate a ceasefire with Red Army Colonel General Vasily Chuikov, who still insists on Germany's unconditional surrender. Goebbels' wife Magda poisons their six children with cyanide capsules before committing suicide with Goebbels. Many officials and soldiers, including Krebs and German diplomat SS-Brigadeführer Walther Hewel commit suicide as well after learning of Germany's defeat. Weidling announces the unconditional surrender of German forces in Berlin not long before Peter discovers that his parents were murdered by a band of Nazi fanatics. The remaining occupants of the bunker attempt to flee the city but soon end up surrounded by the Red Army. Junge is the only occupant who continues her escape, and Peter joins her as they sneak through Red Army soldiers before finding a bicycle and escaping Berlin.

Cast

editNazi Party and civilians

edit- Bruno Ganz as Adolf Hitler

- Alexandra Maria Lara as Traudl Junge

- The real Traudl Junge appears in opening and the closing of the movie via footage from the documentary Im toten Winkel.

- Ulrich Matthes as Joseph Goebbels

- Corinna Harfouch as Magda Goebbels

- Juliane Köhler as Eva Braun

- Birgit Minichmayr as Gerda Christian

- Donevan Gunia as Peter Kranz

- Karl Kranzkowski as Wilhelm Kranz

- Ulrike Krumbiegel as Dorothee Kranz

- Michael Brandner as Hans Fritzsche

- Anna Thalbach as Hanna Reitsch

- Bettina Redlich as Constanze Manziarly

- Elizaveta Boyarskaya as Erna Flegel

- Oliver Stritzel as Johannes Hentschel

- Heino Ferch as Albert Speer

Wehrmacht

edit- Mathias Gnädinger as Hermann Göring

- Dieter Mann as Wilhelm Keitel

- Dietrich Hollinderbäumer as Robert Ritter von Greim

- Christian Redl as Alfred Jodl

- Rolf Kanies as Hans Krebs

- Michael Mendl as Helmuth Weidling

- Justus von Dohnányi as Wilhelm Burgdorf

- Hans H. Steinberg as Karl Koller

- Klaus B. Wolf as Alwin-Broder Albrecht

- Devid Striesow as Fritz Tornow

Schutzstaffel

edit- Ulrich Noethen as Heinrich Himmler

- Thomas Thieme as Martin Bormann

- Christian Hoening as Ernst-Robert Grawitz

- Thomas Kretschmann as Hermann Fegelein

- Alexander Held as Walther Hewel

- André Hennicke as Wilhelm Mohnke

- Matthias Habich as Werner Haase

- Thomas Limpinsel as Heinz Linge

- Thorsten Krohn as Ludwig Stumpfegger

- Jürgen Tonkel as Erich Kempka

- Igor Romanov as Peter Högl

- Igor Bubenchikov as Franz Schädle

- Christian Berkel as Ernst-Günther Schenck

- Fabian Busch as Gert Stehr

- Götz Otto as Otto Günsche

- Heinrich Schmieder as Rochus Misch

Additional cast members in smaller roles include Alexander Slastin as Vasily Chuikov, Elena Dreyden as Inge Dombrowski, Norbert Heckner as Walter Wagner, Silke Nikowski as Frau Grawitz, Leopold von Buttlar as Sohn Grawitz, Veit Stübner as Tellermann, Boris Schwarzmann as Matvey Blanter, Vsevolod Tsurilo as Russian Adjutant, Vasily Reutov as Theodor von Dufving. The Goebbels children are portrayed by Alina Sokar (Helga), Charlotte Stoiber (Hilda), Gregory Borlein (Helmut), Julia Bauer (Hedda), Laura Borlein (Holde), and Amelie Menges (Heide).

Production

editDevelopment

editProducer and screenwriter Bernd Eichinger wanted to make a film about Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party for twenty years but was, at first, discouraged after its enormity prevented him from doing so.[6] Eichinger was inspired to begin the filmmaking process after reading Inside Hitler's Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich (2002) by historian Joachim Fest.[7][8][6] Eichinger also based the film on the memoirs of Traudl Junge, one of Hitler's secretaries, called Until the Final Hour: Hitler's Last Secretary (2002).[9][10] When writing the screenplay, he used the books Inside the Third Reich (1969), by Albert Speer,[11] one of the highest-ranking Nazi officials to survive both the war and the Nuremberg trials; Hitler's Last Days: An Eye-Witness Account (1973), by Gerhard Boldt;[12] Das Notlazarett unter der Reichskanzlei: Ein Arzt erlebt Hitlers Ende in Berlin (1995) by Ernst-Günther Schenck; and Soldat: Reflections of a German Soldier, 1936–1949 (1992) by Siegfried Knappe as references.[13]

After completing the script for the film, Eichinger presented it to director Oliver Hirschbiegel. Though he was interested in exploring how the people of Germany "could have plumbed such depths", as a German, Hirschbiegel hesitated to take it as he "reacted to the idea of Nazism as a taboo". Hirschbiegel eventually agreed to helm the project.[14][13]

Casting

editWhen Bruno Ganz was offered the role of Hitler, he was reluctant to accept the part, and many of his friends advised against it,[4][15] but he believed that the subject had "a fascinating side", and ultimately agreed to take the role.[16] Ganz studied the Hitler and Mannerheim recording for four months to properly mimic Hitler's conversational voice and Austrian dialect. Ganz came to the conclusion that Hitler had Parkinson's disease, noting his observation of Hitler's shaky body movements present in the newsreel Die Deutsche Wochenschau, and decided to visit a hospital to study patients with the disease.[16] Ganz auditioned in the casting studio with makeup for half an hour and tested his voice for Hirschbiegel who was convinced by his performance.[4][17]

Alexandra Maria Lara was cast as Traudl Junge; she was given Junge's book Until the Final Hour (2002), which she called her "personal treasure", to read during filming. Before she was cast, she had seen André Heller's documentary film Im toten Winkel which impressed her and influenced her perspective on Junge.[18][19]

Filming and design

editPrincipal photography lasted twelve weeks from September to November 2003, under the working title Sunset.[20][13] The film is set mostly in and around the Führerbunker; Hirschbiegel made an effort to accurately reconstruct the look and atmosphere of World War II through eyewitness accounts, survivors' memoirs, and other historical sources. Hirschbiegel filmed in the cities of Berlin, Munich, and Saint Petersburg, Russia, with a run-down industrial district along the Obvodny Canal used to portray the historical setting in Berlin.[20][21] Hirschbiegel noted the depressing atmosphere surrounding the shoot, finding relief through listening to Johann Sebastian Bach's music.[15] Alexandra Maria Lara also mentioned the depressing and intense atmosphere during filming. To lighten the mood, Lara's colleagues engaged in activities such as football, while Ganz tried to keep a happy mood by retiring during shooting breaks.[19]

The film was produced on a €13.5 million budget.[4] The bunker and Hitler's Wolf's Lair were constructed at Bavaria Studios in Munich by production designer Bernd Lepel.[17][1] The damaged Reich Chancellery was depicted through the use of CGI. Hirschbiegel decided to limit the use of CGI, props and sets so as not to make the set design look like that of a theatre production,[17] explaining:

The only CGI shot that's been used in the film was the one with the [Reich Chancellery] because of course we could not reconstruct that – that's the only thing. I'm very proud of that, because if you do a war movie, you cannot do that and build sets. You feel the cardboard. You feel that it's all made to entertain, and it takes away from that horror that war basically means.[17]

Themes

editAccording to Eichinger, the film's overlying idea was to make a film about Hitler and wartime Germany that was very close to historical truth, as part of a theme that would allow the German nation to save their own history and "experience their own trauma". To accomplish this, the film explores Hitler's decisions and motives during his final days through the perspective of the individuals who lived in the Führerbunker during those times.[22] Eichinger chose not to include mention of the Holocaust because it was not the topic of the film. He also thought it was "impossible" to show the "misery" and "desperation" of the concentration camps cinematically.[23][24]

Portrayal

editDuring production, Hirschbiegel believed that Hitler would often charm people using his personality, only to manipulate and betray them.[15] Many of the people in the film, including Traudl Junge, are shown to be enthusiastic in interacting with Hitler instead of feeling threatened or anxious by his presence and authority. The production team sought to give Hitler a three-dimensional personality, with Hirschbiegel telling NBC: "We know from all accounts that he was a very charming man – a man who managed to seduce a whole people into barbarism."[25] He said Hitler was "like a shell", attracting people with self-pity, but inside the shell was only "an enormous will for destruction".[15]

The film explores the suicides and deaths of the Nazi Party as opposed to the people who choose life. Hitler's provision of cyanide pills to those in the bunker and the Goebbels' murder of their children are shown as selfish deeds while people such as Schenck, who chose to help the injured and escape death, are shown as rational and generous.[26][27] In the DVD commentary, Hirschbiegel said that the events in the film were "derived from the accounts, from descriptions of people" in the bunker.[28] The film also includes an introduction and closing with the real Junge in an interview from Im toten Winkel, where she admits feeling guilt for "not recognizing this monster in time".[27] While the majority of the characters in the film are based on actual people, the character Peter Kranz is fiction as he is based on Alfred Czech, a 12-year-old who saved a dozen of German soldiers from a Russian attack in his home village of Goldenau (now Złotniki, Poland). The character's name may be different, but the scene is real.[29]

Release

editDownfall premiered at the Toronto Film Festival on September 14, 2004.[12][30] After first failing to find a distributor, the film was eventually released on September 16 in Germany by Constantin Film.[8][31] It premiered in the U.S. in Manhattan on February 18, 2005, under Newmarket Films.[32] On its broadcast in the UK, Channel 4 marketed it with the strapline: "It's a happy ending. He dies."[33]

Box office and awards

editDownfall sold nearly half a million tickets in Germany for its opening weekend and attracted 4.5 million viewers in the first three months.[34][30] The final North American gross was $5,509,040, while $86,671,870 was made with its foreign gross.[5] The film made $93.6 million altogether.[13]

Downfall was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 77th Academy Awards.[35] It won the 2005 BBC Four World Cinema competition.[36] The film was also ranked number 48 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.[37]

Home media

editThe film was released on DVD in August 2 2005 by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment.[38] Shout! Factory released a collector's edition Blu-ray in March 2018, with a "making-of" featurette, cast and crew interviews, and audio commentary from director Oliver Hirschbiegel.[39] The film was released on Ultra HD Blu-ray in Germany in 2024.

TV Extended Version

editIn addition to the theatrical version, which has a length of 150 minutes, there was also an extended version produced especially for television. First aired by Das Erste on 19 October 2005, the 25 minutes longer Extended Version was played in two parts each with a length of approx. 90 minutes.[40][41] Later it was also released on DVD. The Extended Version features many new scenes in the bunker and shows more of the bombed-out Berlin.[42]

Reception

editCritical response

editThe review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 90% based on 141 reviews from critics, with a weighted average of 8/10. The website's consensus reads, "Downfall is an illuminating, thoughtful and detailed account of Hitler's last days."[43] On Metacritic, the film was awarded the "Must-See" badge, holding a weighted average of 82 out of 100 based on 35 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[44]

Reviews for the film were often very positive,[45] despite debate surrounding the film from critics and audiences upon its release ().[46][24] Ganz's portrayal of Hitler was singled out for praise;[47][48][49] David Denby for The New Yorker said that Ganz "made the dictator into a plausible human being".[50] Addressing other critics like Denby, Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert said the film did not provide an adequate portrayal of Hitler's actions, because he felt no film could, and that no response would be sufficient. Ebert said Hitler was, in reality, "the focus for a spontaneous uprising by many of the German people, fueled by racism, xenophobia, grandiosity and fear".[51]

Hermann Graml, history professor and former Luftwaffe helper, praised the film and said that he had not seen a film that was "so insistent and tormentingly alive". Graml said that Hitler's portrayal was presented correctly by showing Hitler's will "to destroy, and his way of denying reality".[52] Julia Radke of the German website Future Needs Remembrance praised the film's acting and called it well crafted and a solid Kammerspielfilm, though it could lose viewer interest due to a lack of concentration on the narrative perspective.[53] German author Jens Jessen said that the film "could have been stupider" and called it a "chamber play that could not be staged undramatically". Jessen also said that it was not as spectacular as the pre-media coverage could have led one to believe, and it did not arouse the "morbid fascination" the magazine Der Spiegel was looking for.[54]

Hitler biographer Sir Ian Kershaw wrote in The Guardian that the film had enormous emotive power, calling it a triumph and "a marvellous historical drama". Kershaw also said that he found it hard to imagine anyone would find Hitler to be a sympathetic figure in his final days.[31] Wim Wenders, in a review for the German newspaper Die Zeit, said the film was absent of a strong point of view for Hitler which made him harmless, and compared Downfall to Resident Evil: Apocalypse, stating that in Resident Evil the viewer would know which character was evil.[4][46]

Humanization concerns

editThey just got it wrong. Bad people do not walk around with claws like vicious monsters, even though it might be comforting to think so. Everyone intelligent knows that evil comes along with a smiling face.[15]

Downfall was the subject of dispute by critics and audiences in Germany before and after its release, with many concerned regarding Hitler's portrayal in the film as a human being with emotions in spite of his actions and ideologies.[46][31][55] The portrayal sparked debate in Germany due to publicity from commentators, film magazines, and newspapers,[25][56] leading the German tabloid Bild to ask the question, "Are we allowed to show the monster as a human being?"[25]

It was criticized for its scenes involving the members of the Nazi party,[23] with author Giles MacDonogh criticizing the portrayals as being sympathetic towards SS officers Wilhelm Mohnke and Ernst-Günther Schenck,[57] the former of whom was accused of murdering a group of British prisoners of war in the Wormhoudt massacre.[N 1] At a discussion in London, Hirschbiegel said that the allegations that Schenck had performed unethical medical experiments were unproven.[60] Russian press visited the set, making the producers uneasy and occasionally defensive. Yana Bezhanskay, director of Globus Film, Constantin's Russian partner, raised her voice to Russian journalists and said: "This is an antifascist film and nowhere in it do you see Hitler praised."[20]

Cristina Nord from Die Tageszeitung criticized the portrayal, and said that though it was important to make films about perpetrators, "seeing Hitler cry" had not informed her on the last days of the Third Reich.[61] Some have supported the film: Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, director of Hitler: A Film from Germany (1977), felt the time was right to "paint a realistic portrait" of Hitler.[15] Eichinger replied to the response from the film by stating that the "terrifying thing" about Hitler was that he was human and "not an elephant or a monster from Mars".[8] Ganz said that he was proud of the film; though he said people had accused him of "humanizing" Hitler.[56]

When Rochus Misch, Hitler's bodyguard from 1940, was asked about the film's historical accuracy in a 2005 interview, he stated that although it was factually accurate, the film had “Americanized” what had happened in real life. He noted that Hitler never screamed in the bunker and that the bunker was generally quiet. Misch opined that the film portrayal of the murder of the Goebbels children was inaccurate as he alleged that it was Frau Goebbels who was behind the murder as opposed to both Frau and Joseph Goebbels. Furthermore, whilst Misch had contemplated suicide as depicted in the film, the event occurred differently in reality.[62]

Parodies

editDownfall is well known for its rise in popularity due to many internet parody videos and memes which use several scenes in the film: when Hitler phones General der Flieger Karl Koller about Berlin's April 20 bombardment; when Hitler discusses a counterattack against advancing Soviet forces with his generals; where Hitler becomes angry after hearing that Steiner's attack never happened, due to a lack of forces; when Hitler hears Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring's telegram; when Hitler is having dinner and discovers Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler secretly made a surrender offer to the Western Allies; and where Hitler orders Otto Günsche to find SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein. In the videos the original German audio is retained, but new subtitles are added so that Hitler and his subordinates seem to be reacting to an issue or setback in present-day politics, sports, entertainment, popular culture, or everyday life.[63][64][65][66] In addition, some users combine footage from the film with other sources, dub the German dialogue over video games and/or footage from other films and TV series, or edit images of the characters onto pre-existing or animated footage, often for greater comic effect.[67][68][65]

Hirschbiegel spoke positively about these parodies in a 2010 interview with New York magazine, saying that many of them were funny and a fitting extension of the film's purpose.[69] Nevertheless, Constantin Film asked video sites to remove them.[63] The producers initiated a removal of parody videos from YouTube in 2010.[70] This prompted more posting of parody videos of Hitler complaining that the parodies were being taken down, and a resurgence of the videos on the site.[68]

One particular parody was the subject of BP Refinery v Tracey, where a BP employee named Scott Tracey was terminated from his job for a video satirising collective bargaining negotiations at the company he was working in. Tracey managed to successfully appeal his unfair dismissal to the Full Federal Court who decided that the video in question was not offensive, and had his job reinstated and received $200,000 in compensation.[71]

See also

edit- Adolf Hitler in popular culture

- Vorbunker

- The Bunker – 1981 English language TV movie that broadly depicts the same events starring Anthony Hopkins as Adolf Hitler

References

editInformational notes

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Elley, Derek (16 September 2004). "Downfall". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ a b "DOWNFALL (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 24 December 2004. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ "Downfall (2004)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Eichinger-Film "Der Untergang": Bruno Ganz spielt späten Hitler". Spiegel Online (in German). 16 April 2003. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ a b "DOWNFALL". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ a b Landler, Mark (15 September 2004). "The All-Too-Human Hitler, on Your Big Screen". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Vande Winkel 2007, p. 187.

- ^ a b c Summers, Sue (20 March 2005). "Now the Germans have their say". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Denby, David (14 February 2005). "Back in the Bunker". The New Yorker. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Machtans & Ruehl 2012.

- ^ Oren, Michael B. (4 July 2005). "Pass the Fault". The New Republic. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ a b Bathrik, David (1 November 2007). "Whose Hi/story Is It? The U.S. Reception of Downfall". New German Critique. 34 (3). Duke University Press: 1–16. doi:10.1215/0094033X-2007-008. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d Niemi 2018.

- ^ Trapani, Salvatore (5 February 2005). "The Downfall – Interview: Oliver Hirschbiegel • Director". Cineuropa. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Johnston, Sheila (30 April 2015). "The dangers of portraying Hitler". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ a b Diver, Krysia; Moss, Stephen (25 March 2003). "Desperately seeking Adolf". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d Cavagna, Carlo. "Interviews: DOWNFALL". AboutFilm.Com. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Bonke, Johannes (17 September 2004). "Alexandra Maria Lara über ihr Gefühls-Chaos" (in German). Filmreporter.de. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b Sarkar, David (25 August 2004). "Das Böse kann niemals eindimensional sein" (in German). Planet Interview. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Varoli, John (7 October 2003). "A War-Torn Berlin Reborn in Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Meza, Ed (12 August 2003). "Hitler pic lands in Russia". Variety. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Mazierska 2011.

- ^ a b "Controversial Hitler Film Opens Across Germany". Deutsche Welle. 17 September 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ a b Borcholte, Andreas (15 September 2004). ""Der Untergang": Die unerzählbare Geschichte". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Eckardt, Andy (16 September 2004). "Film showing Hitler's soft side stirs controversy". NBC News. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ Vande Winkel 2007.

- ^ a b Bangert 2014.

- ^ Fuchs, Cynthia (3 August 2005). "Downfall (2004)". PopMatters. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Fordy, Tom. "'I never thought people would empathise with Hitler': The truth about the Führer's Downfall". The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ a b Bendix 2007.

- ^ a b c Kershaw, Ian (17 September 2004). "The human Hitler". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (18 February 2005). "The Last Days of Hitler: Raving and Ravioli". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Hitler: The Lost Files". The Irish Times. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "German film on Hitler's demise a box office hit". The Irish Times. 20 September 2004. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ "Hitler Film Wins Oscar Nomination". DW. 26 January 2005. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ "Downfall wins BBC world film gong". BBC. 26 January 2006. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema – 48. Downfall". Empire.

- ^ Atanasov, Svet (8 August 2005). "Downfall". DVD Talk. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ "Downfall Collector's Edition Blu-ray Detailed". Blu-ray.com. 12 February 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Entry for the Extended Version of “Downfall" in the Online-Filmdatenbank.

- ^ Uwe Mantel (20 October 2005). ""Der Untergang": Erster Teil des Hitler-Films erfolgreich". DWDL.de (in German). Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Comparison between the theatrical version and the extended version of “Downfall" on Movie-Censorship

- ^ "Downfall (Der Untergang) (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ "Downfall Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Vande Winkel 2007, p. 212.

- ^ a b c "A film depicting Adolf Hitler's human side is attracting crowds and stirring debate in Germany". Columbia University. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (1 April 2005). "Downfall Review". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Newman, Kim (10 May 2017). "Downfall Review". Empire. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Smithey, Cole (9 May 2005). "German Filmmakers do Justice to the Fall of Hitler's Empire". Smart New Media.

- ^ Denby, David (14 February 2005). "David Denby's comments on Der Untergang". The New Yorker. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (11 March 2005). "Downfall". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ ""Der Untergang": Faktisch genau, dramaturgisch lau". Der Spiegel (in German). 16 August 2004. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Radke, Julia (1 November 2004). "Hirschbiegel: Der Untergang. Filmrezension". Future Needs Remembrance (in German). Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Jessen, Jens [in German] (26 August 2004). "Stilles Ende eines Irren unter Tage". Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Vande Winkel 2007, p. 208.

- ^ a b "My Hitler part in 'Downfall'". The Irish Times. 26 March 2005. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Eberle & Uhl 2005, p. xviii.

- ^ Weale 2012.

- ^ Fischer 2008, p. 26.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (5 April 2005). "Bunker film 'is too kind to Nazis'". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Furlong, Ray (16 September 2004). "'Human' Hitler disturbs Germans". BBC. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ "Hitler's bodyguard" https://www.salon.com/2005/02/21/nazi_3/ Salon

- ^ a b Finlo Rohrer (13 April 2010). "The rise, rise and rise of the Downfall Hitler parody". BBC News. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Internetting: a user's guide #18 – How downfall gained cult status". The Guardian. London. 5 July 2013. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Kobra – Del 2 av 12: Hitlerhumor" (in Swedish). SVT Play. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ Brady, Tara (31 July 2015). "Oliver Hirschbiegel: from Hitler to Princess Diana and back again". The Irish Times. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ Boutin, Paul (25 February 2010). "Video Mad Libs With the Right Software". The New York Times. pp. B10. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

In various home-subtitled remakes over the last few years, Hitler explodes when told that the McMansion he was trying to flip is in foreclosure, that the band Oasis has split up, that the Colts lost the Super Bowl or that people keep making more "Downfall" parodies.

- ^ a b Evangelista, Benny (23 July 2010). "Parody, copyright law clash in online clips". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Rosenblum, Emma (15 January 2010). "The Director of Downfall Speaks Out on All Those Angry YouTube Hitlers". New York. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ Finlo Rohrer (21 April 2010). "Downfall filmmakers want YouTube to take down Hitler spoofs". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ Zhou, Naaman (15 November 2019). "BP worker fired over Downfall video appeals, saying Fair Work did not understand meme". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

Bibliography

- Bangert, Axel (2014). The Nazi Past in Contemporary German Film: Viewing Experiences of Intimacy and Immersion. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781571139054.

- Bendix, John (Spring 2007). "Facing Hitler: German Responses to 'Downfall'". German Politics and Society. 25 (1 (82)): 70–89. doi:10.3167/gps.2007.250104. JSTOR 23742889.

- Bösch, Frank (2007). "Film, NS-Vergangenheit und Geschichtswissenschaft. Von Holocaust zu Der Untergang". Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. 55 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1524/vfzg.2007.55.1.1. ISSN 0042-5702.

- Fischer, Thomas (2008). Soldiers of the Leibstandarte. J. J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0921991915.

- Fisher, Jaimey; Prager, Brad (2010). The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and Its Politics at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814333778.

- Eberle, Henrik; Uhl, Matthias, eds. (2005). The Hitler Book: The Secret Dossier Prepared for Stalin. Translated by MacDonogh, Giles. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-366-8.

- Machtans, Karolin; Ruehl, Martin A. (30 November 2012). Hitler – Films from Germany: History, Cinema and Politics since 1945. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 9781137032386.

- Mazierska, Ewa (12 July 2011). European Cinema and Intertextuality: History, Memory and Politics. Springer. ISBN 9780230319547.

- Niemi, Robert (2018). 100 Great War Movies: The Real History Behind the Films. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440833861.

- Weale, Adrian (2012). Army of Evil: A History of the SS. New York; Toronto: NAL Caliber (Penguin Group). ISBN 978-0-451-23791-0.

Further reading

- Bischof, Willi, ed. (2005). Filmri:ss; Studien über den Film "Der Untergang". Münster: Unrast Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89771-435-9. (studies about the Film)

- Fest, Joachim (2004). Inside Hitler's Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-13577-5.

- Fischer, Thomas (2008). Soldiers of the Leibstandarte. J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-921991-91-5.

- Junge, Traudl; Müller, Melissa; Bell, Anthea (2004). Until the Final Hour: Hitler's Last Secretary. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55970-728-2.

- O'Donnell, James P (2001) [1978]. The Bunker: The History of the Reich Chancellery Group, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-25719-7.

- Vande Winkel, Roel (2007). "Hitler's Downfall, a film from Germany (Der Untergang, 2004)". In Engelen, Leen; Vande Winkel, Roel (eds.). Perspectives on European Film and History. Gent: Academia Press. pp. 182–219. ISBN 978-90-382-1082-7. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

External links

edit- Der Untergang (Downfall) at IMDb

- Germania – Vision and Crime – exhibition by Berliner Unterwelten. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015.

- Richardson, Jay (4 September 2005). "Interview with director Oliver Hirschbiegel". Future Movies.