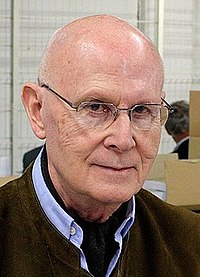

Dominique Venner (French: [vɛnɛʁ]; 16 April 1935 – 21 May 2013) was a French historian, journalist, and essayist. Venner was a member of the Organisation armée secrète and later became a European nationalist, founding the neo-fascist and white nationalist Europe-Action, before withdrawing from politics to focus on a career as a historian.[1] He specialized in military and political history. At the time of his death, he was the editor of the La Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire, a bimonthly history magazine.

Dominique Venner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 16 April 1935 Paris, France |

| Died | 21 May 2013 (aged 78) Paris, France |

| Cause of death | Suicide by gunshot |

| Occupation | Writer, historian, editor, soldier, activist |

| Genre | Non-fiction (History) |

| Notable works | Le Cœur rebelle, Baltikum: dans le Reich de la défaite, le combat des corps-francs, 1918-1923, Histoire et Tradition des Européens: 30000 ans d'identité, Ernst Jünger: Un autre destin européen |

| Notable awards | Broquette Gonin Price, 1981 (issued by the Académie française) |

On 21 May 2013, Venner outraged by the recent legalization of same-sex marriage in France, which he believed would result in a white genocide, killed himself inside the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris. In a suicide note, he said his death was an act in "defence of the traditional family" and in the "fight against illegal immigration". Venner believed that the far-right had become too soft and that peaceful demonstrations against same-sex marriage were not enough prevent a "total replacement of the population of France, and of Europe." The leader of the far-right National Front, Marine Le Pen, described the suicide as the act of a broken man desperately seeking to "re-awaken" his countrymen.[2]

Youth

editThe son of an architect who had been a member of Doriot's Parti populaire français[3] (the PPF), Venner volunteered to fight in the Algerian War, and served until October 1956. Upon his return to France he joined the Jeune Nation (Young Nation) movement. Following the violent suppression of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution he participated in the ransacking of the office of the French Communist Party on 7 November 1956.[4] Along with Pierre Sidos, he helped found the short-lived Parti Nationaliste (Nationalist Party) and was involved with the Mouvement populaire du 13-mai (Popular Movement of May 13) led by General Chassin. As a member of the Organisation armée secrète, he was jailed for 18 months in La Santé Prison as a political undesirable. He was freed in 1962.

Political writing and activism

editUpon his release from prison in the autumn of 1962, Venner wrote a manifesto entitled Pour une critique positive (Towards a positive critique), which has been compared by some to Vladimir Lenin's What is to be done?,[5] as it became a "foundational text of a whole segment of the ultra-right".[6] In the manifesto, Venner explored the reasons for the failure of the April 1961 coup and the divide that existed between "nationals" ("nationaux") and "nationalists" ("nationalistes") and called for the creation of a single revolutionary and nationalist organisation, which would be "monolithic and hierarchical" and composed of young, "disciplined and devoted" nationalist militants who would be ready for combat.

In January 1963, he created with Alain de Benoist a movement and magazine called Europe-Action, which he later led. He went on to found the Éditions Saint-Just, which operated in tandem with Europe-Action, and which was composed of nationalists, Europeanists, members of the Fédération des étudiants nationalistes ("Federation of Nationalist Students"), former OAS members, young militants and former collaborators like Lucien Rebatet. He was a member of Groupement de recherche et d'études pour la civilisation européenne (GRECE) (Research and Study Group for European Civilization) from its beginning until the 1970s.[7] He also created, with Thierry Maulnier, the Institut d'études occidentales (IEO) (Institute of Western Studies), and its revue, Cité-Liberté (City-Liberty), founded in 1970. The IEO was an enterprise that worked in parallel and in tandem with GRECE,[8] and the organisation attracted numerous intellectuals, including Robert Aron, Pierre Debray-Ritzen, Thomas Molnar, Jules Monnerot, Jules Romains, Louis Rougier, Raymond Ruyer and Paul Sérant. The IEO was anti-communist, pitted itself against what it saw as "mental subversion" and supported Western values.[9] The IEO dissolved in 1971, the same year Venner ceased all political activities in order to focus on his career as an historian.

Career as historian

editVenner was a specialist regarding weaponry and hunting and wrote several books on these subjects. His principal historical works were: Baltikum (1974), Le Blanc Soleil des vaincus (The White Sun of the Vanquished) (1975), Le Cœur rebelle (The Rebel Heart) (1994), Gettysburg (1995), Les Blancs et les Rouges (The Whites and the Reds) (1997), Histoire de la Collaboration (History of the Collaboration) (2000) and Histoire du terrorisme (History of Terrorism) (2002). His Histoire de l'Armée rouge (History of the Red Army) won the Prix Broquette-Gonin of history awarded by the Académie française in 1981.

In 1995, and with the advice of his friend François de Grossouvre, Venner published Histoire critique de la Résistance (Critical History of the Resistance), which highlighted the strong influence and presence of French nationalists in the Resistance (often called "vichysto-résistants"). The work was criticised by some for failing to probe Marshal Philippe Pétain's attitude towards the Resistance.[10]

In 2002, Venner wrote Histoire et tradition des Européens (History and Tradition of the Europeans), in which he set out what he believed to be the common cultural bases of European civilisation, and outlined his theory of "traditionalism" (a concept that, inter alia, assesses the specificities of each society and civilisation).

Venner served as editor in chief of the revue Enquête sur l'histoire (Study of History, or Historical Inquest) until its dissolution in the late 1990s. In 2002, he created La Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire (The New Historical Revue, temporarily renamed the NRH in 2006), a bimonthly magazine devoted to historical topics. The Revue has featured Bernard Lugan, Jean Tulard, Aymeric Chauprade, Jean Mabire, François-Georges Dreyfus, Jacqueline de Romilly and former ministers Max Gallo and Alain Decaux. He was a co-host of a radio program on Radio Courtoisie.

Some of his books have been translated into English, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Russian and Ukrainian.

Critical reception

editAs noted above, Venner has been awarded a prestigious prize by l'Académie française for one of his historical works.

When it appeared that the NRH might be dissolved, journalist Christian Brosio (among others) sprang to its defence, claiming the revue was unique in its aesthetic presentation, in its originality in the treatment of subjects covered, the depth of its analysis and the quality of its contributors.[11] Political scientist Gwendal Châton[12] has claimed that Venner has "integrated himself in the strategy of seeking out a newfound respectability: that of an intellectual", which he has used to "instrumentalise history to put history at the service of cultural struggle"[13] and that Venner's "traditionalism" and adherence to "European history and tradition" are a mere "rhetorical screen" designed to "mask" an "ideological continuity" from his earlier political activism.[14] Châton also alleges that Venner uses his historical revues to "manipulate history" in the guise of various rhetorical techniques.[15]

University Professor Christopher Flood has noted that the revue generally adheres to a right-wing outlook, commenting: "[...] the overall flavour has been persistently, if subtly, revisionist".[16] While adhering to Chauprade's views on the conflict of civilisations, the NRH does not contain explicitly racist themes[dubious – discuss]. In an editorial Venner commented that "The Japanese, the Jews, the Hindus and other peoples possess that treasure that has permitted them to confront the perils of history without disappearing. It is their misfortune that the majority of Europeans, and especially the French, are so impregnated with universalism that this treasure is lacking"[better source needed][17]

Suicide

editOn 21 May 2013, about 16:00, Venner committed suicide by firearm in the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris,[18] which led to the evacuation of approximately 1,500 people from the cathedral.[19] He had been an opponent of Muslim immigration to France and Europe, as well as what he believed to be the Americanization of European values and — most recently — the legalization of same-sex marriage in France. Despite the choice of Notre Dame as the place of his suicide, Venner was not a Christian.[20] He was a practicing pagan but also an admirer of Christian civilization.[21]

Only hours earlier, he had left a post on his blog, on the subject of forthcoming protests against the legalization of same-sex marriage.[22] In the post, Venner approves of the demonstrators' outrage at an "infamous law", but expresses doubt as to the efficacy of street protests to effect social change. He rebukes the protesters for ignoring the threat of "Afro-Maghreb immigration", which he predicts will lead to a "total replacement of the population of France, and of Europe."[23] He warns, "Peaceful street protests will not be enough to prevent it. [...] It will require new, spectacular, and symbolic actions to rouse people from their complacency [...] We enter into a time when words must be backed up by actions."[23]

In a letter sent to his colleagues at Radio Courtoisie, he characterizes his suicide as a rebellion "against pervasive individual desires that destroy the anchors of our identity, particularly the family, the intimate base of our multi-millennial society."[22] He explains his decision to commit suicide inside the cathedral: "I chose a highly symbolic place that I respect and admire."[24] According to the rector of Notre Dame de Paris, Venner left behind a letter for investigators.[25] It was subsequently reported that Venner was suffering from a serious illness at the time of his suicide.[22]

Shortly after his death was reported, a number of far-right personalities paid tribute to Venner and commended his public suicide. Marine Le Pen issued a tweet: "All our respect to Dominique Venner, whose final gesture, eminently political, was to try to awaken the people of France."[26] Bruno Gollnisch described him as an "extremely brilliant intellectual" whose death was "a protest against the decadence of our society."[26]

Others sought to distance themselves from Venner. Frigide Barjot, spokesperson for the anti-gay marriage movement "La Manif pour tous", told reporters that Venner had never been a member of her movement:[27] "This gentleman belonged to a movement known as the French Spring, which has nothing to do with us, and which we condemned long ago." She described his suicide as "an isolated personal act, very violent, ostentatious, and desperate."[27]

Works

edit- Guide de la contestation: les hommes, les faits, les événements, Robert Laffont, Paris, 1968, 256 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Ils sont fous, ces gauchistes ! Pensées. Choisies et parfois commentées par Dominique Venner, Éd. de la Pensée moderne, Paris, 1970, 251 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Guide de la politique, Balland, Paris, 1972, 447 p. + 12 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Pistolets et revolvers, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 1, Paris, 1972, 326 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Les Corps d'élite du passé (dir.), Balland, Paris, 1972, 391 p. [pas d'ISBN] – Réunit : Les Chevaliers teutoniques, par Jean-Jacques Mourreau, Janissaires, par Philippe Conrad, Mousquetaires, par Arnaud Jacomet, Grenadiers de la Garde, par Jean Piverd, et Cadets, par Claude Jacquemart.

- Monsieur Colt, Balland, coll. " Un Homme, une arme ", Paris, 1972, 242 p. + 40 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Carabines et fusils de chasse, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 2, Paris, 1973, 310 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Baltikum: dans le Reich de la défaite, le combat des corps-francs, 1918-1923, Robert Laffont, coll. " L'Histoire que nous vivons ", Paris, 1974, 365 p. + 16 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Armes de combat individuelles, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 3, Paris, 1974, 310 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Le Blanc Soleil des vaincus: l'épopée sudiste et la guerre de Sécession, 1607-1865, La Table ronde, Paris, 1975, 300 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Les Armes de la Résistance, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 4, Paris, 1976, 330 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- [Collectif], Les Armes de cavalerie (dir.), Argout, Paris, 1977, 144 p. ISBN 2-902297-05-X. Hors-série n° 4 de la revue Gazette des armes

- Les Armes blanches du IIIe Reich, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 5, Paris, 1977, 298 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Westerling: guérilla story, Hachette, coll. " Les Grands aventuriers ", Paris, 1977, 319 p. ISBN 2-01-002908-9.

- Les Armes américaines, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 6, Paris, 1978, 309 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Les Corps-francs allemands de la Baltique: la naissance du nazisme, Le Livre de poche, n° 5136, Paris, 1978, 508 p. ISBN 2-253-01992-5.

- Dominique Venner, Thomas Schreiber et Jérôme Brisset, Grandes énigmes de notre temps, Famot, Genève, 1978, 248 p. + 24 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Les Armes à feu françaises, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 7, Paris, 1979, 334 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Les Armes russes et soviétiques, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 8, Paris, 1980, 276 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Le Grand livre des armes, Jacques Grancher, Paris, 1980, 79 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Histoire de l'Armée rouge. Tome 1: La Révolution et la guerre civile: 1917-1924, Plon, Paris, 1981, 301 p. + 16 p. ISBN 2-259-00717-1.

- Le Mauser 96, Éd. du Guépard, Paris, 1982, 94 p. ISBN 2-86527-027-0.

- Dagues et couteaux, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 9, Paris, 1983, 318 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Histoire des armes de chasse, Jacques Grancher, Paris, 1984, 219 p. + 16 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Le Guide de l'aventure, Pygmalion, Paris, 1986, [pagination non connue] ISBN 2-85704-215-9.

- Les Armes blanches: sabres et épées, Éd. de la Pensée moderne et Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 10, Paris, 1986, 317 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Les Armes de poing: de 1850 à nos jours, Larousse, Paris, 1988, 198 p. ISBN 2-03-506214-4.

- Treize meurtres exemplaires: terreur et crimes politiques au XXe siècle, Plon, Paris, 1988, 299 p. ISBN 2-259-01858-0.

- L'Assassin du président Kennedy, Perrin, coll. "Vérités et légendes", Paris, 1989, 196 p. + 8 p. ISBN 2-262-00646-6.

- L'Arme de chasse aujourd'hui, Jacques Grancher, coll. " Le Livre des armes " n° 11, Paris, 1990, 350 p. [pas d'ISBN]

- Les Beaux-arts de la chasse, Jacques Grancher, coll. " Passions ", Paris, 1992, 241 p. [ISBN erroné]

- Le Couteau de chasse, Crépin-Leblond, coll. " Saga des armes et de l'armement ", Paris, 1992, 134 p. ISBN 2-7030-0099-5.

- Le Cœur rebelle, Les Belles-Lettres, Paris, 1994, 201 p. ISBN 2-251-44032-1.

- Gettysburg, Éd. du Rocher, Monaco et Paris, 1995, 321 p. ISBN 2-268-01910-1.

- Histoire critique de la Résistance, Pygmalion, Collection rouge et blanche, Paris, 1995, 500 p. ISBN 2-85704-444-5.

- Les armes qui ont fait l'histoire. Tome 1, Crépin-Leblond, coll. " Saga des armes et de l'armement ", Montrouge, 1996, 174 p. ISBN 2-7030-0148-7.

- Revolvers et pistolets américains: l'univers des armes (avec la collaboration de Philippe Fossat et Rudy Holst), Solar, coll. " L'Univers des armes ", 1996, 141 p. ISBN 2-263-02429-8.

- Histoire d'un fascisme allemand: les corps-francs du Baltikum et la révolution (sous-titré du Reich de la défaite à la nuit des longs couteaux 1918-1934), Pygmalion, Collection rouge et blanche, Paris, 1996, 380 p. + 16 p. ISBN 2-85704-479-8.

- Les Blancs et les Rouges: histoire de la guerre civile russe, 1917-1921, Pygmalion, Collection rouge et blanche, Paris, 1997, 396 p. + 16 p. ISBN 2-85704-518-2.

- Encyclopédie des armes de chasse: carabines, fusils, optique, munitions, Maloine, Paris, 1997, 444 p. ISBN 2-224-02363-4.

- Dictionnaire amoureux de la chasse, Plon, coll. " Dictionnaire amoureux ", Paris, 2000, 586 p. ISBN 2-259-19198-3.

- Histoire de la Collaboration (suivi des dictionnaires des acteurs, partis et journaux), Pygmalion, Paris, 2000, 766 p. ISBN 2-85704-642-1.

- Histoire du terrorisme, Pygmalion et Gérard Watelet, Paris, 2002, 248 p. ISBN 2-85704-749-5.

- Histoire et tradition des Européens: 30 000 ans d'identité, Éd. du Rocher, Monaco et Paris, 2002, 273 p. ISBN 2-268-04162-X.

- De Gaulle: la grandeur et le néant: essai, Éd. du Rocher, Monaco et Paris, 2004, 304 p. ISBN 2-268-05202-8.

- Le Siècle de 1914. Utopies, guerres et révolutions en Europe au XXe siècle, Pygmalion, Paris, 2006, 408 p. ISBN 2-85704-832-7.

- Le Choc de l’Histoire: Religion, mémoire, identité. Via Romana, Versailles, 2011. 179 p. ISBN 979-1090029071.

- Pourquoi je me suis tué, Avant-propos par un dernier verre, Last Litany Livres, La Chaire, 2013, 2 p. ISBN 1-61173-616-1.

References

edit- ^ John Lichfield (21 May 2013). "Far-right French historian, 78-year-old Dominique Venner, commits suicide in Notre Dame in protest against gay marriage". Independent. London. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ "France reacts to Dominique Venner's shock 'gesture'". BBC News. 22 May 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Notice biographique dans le Tome 1 du Dictionnaire de la politique française d'Henry Coston (1967).

- ^ Les Actualités françaises [archive], 14 November 1956; La Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire n°27, p. 52.

- ^ Pierre Milza, Fascismes français, passé et présent, Flammarion, 1988, p. 320

- ^ Pierre Milza, L'Europe en chemise noire. Les extrêmes droites en Europe de 1945 à aujourd'hui, Flammarion, collection "Champs", 2002, p. 193. In footnote 1 on p. 443 Milza notes, inter alia: "In December 1982, during the Congress of the Party of New Forces, Roland Hélie, of the Party's political executive, suggested members reread Venner's text", "En décembre 1982, lors du congrès du Parti des forces nouvelles, Roland Hélie, membre du bureau politique, conviait les militants à une relecture du texte de Venner". Cf. Pierre-André Taguieff, "La stratégie culturelle de la "Nouvelle Droite" en France (1968-1983)", in Vous avez dit fascismes ?, ed. Robert Badinter, Paris, Arthaud/Montalba, 1984, pp. 13-52.

- ^ Nouvelle École, août-septembre 1968.

- ^ According to Pierre-André Taguieff

- ^ see Pierre-André Taguieff, Sur la Nouvelle Droite. Jalons d'une analyse critique, "Descartes et cie", 1994.

- ^ Bénédicte Vergez-Chaignon, Les Vichysto-résistants: de 1940 à nos jours, Perrin, 2008, p. 721.

- ^ "Une revue d'histoire menacée", Valeurs actuelles, 28 juillet 2006.

- ^ Gwendal Châton, "L'histoire au prisme d'une mémoire des droites extrêmes: Enquête sur l'Histoire et La Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire, deux revues de Dominique Venner", dans Michel J. (dir.), Mémoires et Histoires. Des identités personnelles aux politiques de reconnaissance, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, coll. "Essais", 2005, pp. 213-243.

- ^ Gwendal Châton, "L'histoire au prisme d'une mémoire des droites extrêmes: Enquête sur l'Histoire et La Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire, deux revues de Dominique Venner", dans Michel J. (dir.), Mémoires et Histoires. Des identités personnelles aux politiques de reconnaissance, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, coll. "Essais", 2005, pp. 221-222.

- ^ Gwendal Châton, "L'histoire au prisme d'une mémoire des droites extrêmes: Enquête sur l'Histoire et La Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire, deux revues de Dominique Venner", dans Michel J. (dir.), Mémoires et Histoires. Des identités personnelles aux politiques de reconnaissance, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, coll. "Essais", 2005, p. 227.

- ^ Gwendal Châton, "L'histoire au prisme d'une mémoire des droites extrêmes: Enquête sur l'Histoire et La Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire, deux revues de Dominique Venner", dans Michel J. (dir.), Mémoires et Histoires. Des identités personnelles aux politiques de reconnaissance, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, coll. "Essais", 2005, p. 233

- ^ Journal of European Studies, 35(2), pp. 221-236.

- ^ ("Les Japonais, les Juifs, les Hindous et d'autres peuples possèdent ce trésor qui leur a permis d'affronter les périls de l'histoire sans disparaître. Pour leur malheur, la plupart des Européens, particulièrement les Français, imprégnés qu'ils sont d'universalisme, en sont dépourvus"). Venner, La NRH, n°8 (éditorial)

- ^ Suicide à Notre-Dame d'un ex-OAS

- ^ Angelique Chrisafis (21 November 2009). "French historian kills himself at Notre Dame Cathedral after gay marriage rant". Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ "France reacts to Dominique Venner's shock 'gesture'". BBC News. 22 May 2013.

- ^ Dominique Venner, « martyr » d’un contre-mai 68

- ^ a b c Un homme se suicide dans la cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris France Info. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ a b La manif du 26 mai et Heidegger

- ^ "Politique - Actualités, vidéos et infos en direct". Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ "Qui est Dominique Venner, le suicidé de la cathédrale Notre-Dame". Huffington Post (in French). Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Le FN "respecte" le suicidé d'extrême droite de Notre-Dame". Libération (in French). 21 May 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ a b Clémence Olivier (22 May 2013). "Suicide de Notre-Dame: Frigide Barjot prend ses distances avec Dominique Venner". France Info (in French). Retrieved 22 May 2013.

External links

edit- La Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire’s website (in French)

- Suicide note (in French)