This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2007) |

The Diocese of Portland (Latin: Dioecesis Portlandensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory, or diocese, of the Catholic Church for the entire state of Maine in the United States. It is a suffragan diocese of the metropolitan Archdiocese of Boston.

Diocese of Portland Dioecesis Portlandensis | |

|---|---|

| Catholic | |

Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception | |

Coat of arms | |

| Location | |

| Country | |

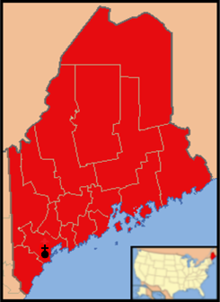

| Territory | Maine |

| Ecclesiastical province | Boston |

| Coordinates | 43°41′05″N 70°16′13″W / 43.68472°N 70.27028°W |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 33,040 sq mi (85,600 km2) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2020) 1,329,000 219,233[1] (16.5%) |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | July 29, 1853 |

| Cathedral | Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Bishop | James T. Ruggieri |

| Metropolitan Archbishop | Richard Henning |

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| portlanddiocese | |

The mother church of the Diocese of Portland is the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Portland. Robert Deeley was installed as bishop in 2014. On May 7, 2024, Deeley retired and James T. Ruggieri was ordained and installed as bishop.

History

edit1600 to 1783

editThe first Catholics in present-day Maine were French Jesuit priests who established missions among the Native American tribes. Saint Sauveur mission was founded on Mount Desert Island in 1613. Assumption Mission was established in Augusta in 1646.[2] The Catholic mission to the Penobscot Native Americans was established in 1688 by Louis-Pierre Thury.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Maine area was contested territory among the British, the French and later the Americans. In 1724, militiamen from the British colonies raided the Abenaki village at Norridgewock, killing scores of inhabitants along with their Jesuit priest, Sébastien Rale.[2]

1783 to 1853

editAfter the American Revolution ended in 1783, Pope Pius VI erected in 1784 the Prefecture Apostolic of the United States, encompassing the entire territory of the new nation. At this point, Maine had become part of the new State of Massachusetts. Pius VI created the Diocese of Baltimore, the first diocese in the United States, to replace the prefecture apostolic in 1789.[3][4] Jean-Louis Lefebvre de Cheverus, the future first bishop of the Diocese of Boston, performed missionary work with the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy in Maine in 1798.

Pope Pius VII erected the Diocese of Boston in 1808, including all of New England in its jurisdiction.[5] In 1820, Maine became its own state.[6][7][8] The early 19th century saw an influx of Irish Catholic immigrants to Maine. In 1833, St. Dominic's became the first Catholic church in Portland.[9] Bangor built its first Catholic Church, St. Michael's, in 1834.[10]

1853 to 1875

editOn July 29, 1853, Pope Pius IX erected the Diocese of Portland. He took New Hampshire and Maine from the Diocese of Boston to create the new diocese, making it a suffragan of the Archdiocese of New York. The pope appointed David Bacon of the Archdiocese of New York as the first bishop of Portland. At the beginning of Bacon's tenure, the diocese held only six priests and eight churches. When he died in 1874, it contained 63 churches, 52 priests, 23 parish schools, and a Catholic population of about 80,000.

Catholics faced bias and violence in some areas of the state. Mobs burned churches in Bath and Lewiston and tarred and feathered the priest in Ellsworth.[2]

1875 to 1900

editOn February 12, 1875, Pope Pius IX elevated the Diocese of Boston to the Archdiocese of Boston.[11] He moved the Diocese of Portland from the Archdiocese of New York to the new archdiocese.[12] That same month, the pope appointed James Healy from Boston as the new bishop. Healy was the first African-American Catholic bishop in the United States, although he kept his background a secret. Healy supervised the setup of the new Diocese of Manchester.

Early into his tenure as bishop, Healy became involved in a conflict with one of his priests, Jean Ponsardin of Biddeford, Maine. Healy suspected that Ponsardin had been stealing money that the diocese gave him to build a new church. After four years of construction, the building only had a basement and unfinished exterior walls.[13] Healy refused to give Ponsardin any more money and suspended him from ministry in October 1877.[13] Ponsardin then appealed his suspension to the Vatican, which created gossip among officials there.[14] Healy finally agreed to pay Ponsardin's debts on the condition that he leave the diocese.[13]

The Ponsardin matter caused such embarrassment for Healy that he submitted his resignation to Leo XIII in 1878, but the pope rejected it.[14] In 1884, Pope Leo XIII erected the Diocese of Manchester and removed New Hampshire from the Diocese of Portland.[15] This action reduced the diocese to its current territory, the State of Maine. By the time Healy died in 1900, the diocese had 92 priests, 86 churches, and 96,400 Catholics.

1900 to 1925

editLeo XIII appointed William O'Connell in 1901 as the new bishop of Portland. After five years as bishop there, he was appointed coadjutor archbishop of Boston. To replace O'Connell, Pope PIus X in 1906 appointed Louis Walsh from Boston. During his tenure as bishop, Walsh established several new parishes and schools, and renovated the cathedral.[16] His tenure was also marked by a wave of immigrants from Poland, Italy, Slovakia, and Lithuania.[17] He met vocal opposition from groups of French Canadian parishioners over the ownership of parish property, leading Walsh to place six of their leaders under interdict.[17]

Walsh's last years as bishop of Portland saw the rise of the Ku Klux Klan as a political force in Maine, particularly in Portland. The diocese's expanding parochial school system became a Klan rallying point. Walsh personally led the fight against the Barwise Bill, a Klan-supported measure in the Maine Legislature that would have prevented the state government from providing the Catholic Church with funds for any purpose. The Barwise Bill and two similar bills by State Senators Owen Brewster and Benedict Maher were defeated, the last in a statewide referendum.[18] Walsh died in 1924.

1925 to 1950

editAuxiliary Bishop John Murray of the Archdiocese of Hartford was appointed by Pope Pius XI in 1925 as bishop of Portland. In 1928, the pope renamed the Diocese of Portland as the Diocese of Portland in Maine. This action was to avoid confusion with the newly erected Archdiocese of Portland in Portland, Oregon.[19]

During his five-year tenure in Portland, Murray established thirty new parishes and a diocesan weekly newspaper, Church World, in 1930. During the Great Depression, Murray organized relief committees to raise money for the homeless and unemployed families. He was forced to mortgage church property to continue funding hospitals, orphanages, and other institutions. Consequently, the diocese accumulated millions of dollars in debt.[20] Murray was appointed archbishop of the Archdiocese of St. Paul in 1932.

Murray's replacement as bishop was Joseph McCarthy of Hartford, named by Pius XI in 1932. McCarthy used his power as a corporation sole to alleviate the debt accumulated by Murray by offering the diocesan property holdings as security for a successful bond issue.[21] By 1936, he had stabilized the diocesan financial situation.[17]

In 1938, McCarthy purchased the former Portland home of railroad executive Morris McDonald as his official residence.[21] He opened numerous elementary schools, high schools, and colleges during his tenure.[17] Pope Pius XII named Daniel Feeney as an auxiliary bishop in 1946; McCarthy delegated most administrative tasks to Feeney due to his own declining health.[17]

1950 to 2000

editIn 1952, Pius XII appointed Feeney as coadjutor bishop of the diocese. When McCarthy died in 1955, Feeney automatically became the new bishop of Portland.

Feeney opened new rectories, convents, schools, social centers, parish halls, and the diocesan chancery. In what he described as his greatest accomplishment, Feeney eliminated the diocesan debt burden dating back to the 1930s. In 1967, Peter Gerety from the Archdiocese of Hartford was appointed by Pope Paul VI as coadjutor bishop of Portland to assist Feeney. When Feeney died in 1969, Gerety automatically succeeded him as bishop of Portland.

As bishop, Gerety implemented the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council by modernizing the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, through the removal of the high altar, cathedra, pulpit, and communion rail.[22] He also provided housing for the elderly and expanded the diocesan Bureau of Human Relations.[22] In 1970, Paul VI appointed Edward O'Leary as auxiliary bishop in Portland. When Gerety left Portland in 1974 to become archbishop of the Archdiocese of Newark, the pope appointed O'Leary as Gerety's replacement.

During his tenure, O'Leary addressed the problem of an increasing Catholic population in the diocese with a decline in the number of priests.[17] He encouraged the greater involvement of laity and women in church administration, and developed a system of parish councils.[23] The diocese also joined the Maine Council of Churches during this time.[17] Pope John Paul II in 1988 appointed Auxiliary Bishop Joseph Gerry from the Diocese of Manchester as the next bishop of Portland when O'Leary resigned that year.

2000 to present

editGerry consolidated Maine parishes in Old Town, Lisbon, and Waterville and opened St. Dominic Regional High School in Auburn in 2002.[17]

After Gerry's retirement in 2004, Pope Benedict XVI appointed Auxiliary Bishop Richard. J. Malone from Boston as the new bishop. In 2012 Benedict XVI named Malone as bishop of the Diocese of Buffalo. In 2013, Pope Francis named Auxiliary Bishop Robert Deeley of Boston, as Malone's successor in Portland.[24]

On February 13, 2024 the appointment of Fr. James T. Ruggieri as Deeley's successor was announced.[25]

Sexual abuse

editIn 1998, nine male former students at the Jesuit-run Cheverus High School in Portland sued the Diocese of Portland, stating that they had been molested by James Talbot, a teacher, and Charles Malia, a coach.[26] The plaintiffs accused both Cheverus and the diocese of hiding information about the abusers, and said that both parties knew about previous accusations against Talbot in Massachusetts. Prior to working in Portland, Talbot had been employed at the Boston College High School in Boston. After receiving accusations of sexual abuse against him in Boston, the Jesuit Order had transferred Talbot to Cheverus.[27][26] By 2002, the Diocese of Portland had paid approximately $700,000 in settlement compensation to the Cheverus victims.[26]

- Talbot admitted his guilt and was fired. In September 2018, Talbot pled guilty to the sex abuse charges in Maine and immediately began serving two concurrent three-year prison sentences.[28][29]

- Malia retired in 1998, but did not admit his guilt until 2000.[30] Due to the statute of limitations in Maine, Malia could not be prosecuted for any of his crimes.[31]

In 2016, the Diocese of Portland settled six lawsuits for sexual abuse for an estimated $1.2 million.[32] The male plaintiffs accused James Vallely from Bangor of sexually abusing them between 1958 and 1977. In 2005, a former priest wrote to the diocese about Vallely, saying that Bishop Feeney had received sexual abuse allegations from five boys about Vallely during the 1950's. Feeney simply transferred Valley out of Bangor to another parish in a different town.[33] In 1993, after several men reported abuse by Vallely to the diocese, he was suspended and sent to Florida for treatment.[34]

By January 2019, the Society of Jesus' Northeast Province in the United States had acknowledged seven accused Jesuit clergy had taught at Cheverus.[35] In August 2019, Bishop Deeley launched an abuse reporting system for the diocese.[36]

In 2002, Gerry removed two priests from ministry in parishes in northern Maine. The two men, Michael Doucette and John Audibert, had admitted to sexually abusing different boys during the 1980s. Gerry said that the men would not be transferred to other parishes.[37] Audibert was permanently from priesthood functions in 2006 and told to live a live of prayer and penance.[38] Doucette was removed permanently from ministry in 2009.[38]

Ronald Paquin, a priest with the Archdiocese of Boston, was convicted in Maine in November 2018 of 11 counts of sexual abuse. During the 1980's, he sexually abused a Massachusetts altar boy during trips they took to Maine. Paquin was sentenced to 16 years in prison in May 2019 .[39][40] In April 2020, the Maine Supreme Judicial Court upheld 10 of Paquin's 11 convictions and vacated one of them.[41][42] The Vatican had laicized Paquin in 2004.[43]

Bishops

editBishops of Portland (in Maine)

edit- David William Bacon (1855–1874)

- James Augustine Healy (1875–1900)

- William Henry O'Connell (1901–1906), appointed Coadjutor Archbishop and later Archbishop of Boston (elevated to Cardinal in 1911)

- Louis Sebastian Walsh (1906–1924)

- John Gregory Murray (1925–1931), appointed Archbishop of Saint Paul

- Joseph Edward McCarthy (1932–1955)

- Daniel Joseph Feeney (1955–1969)

- Peter Leo Gerety (1969–1974), appointed Archbishop of Newark

- Edward Cornelius O'Leary (1974–1988)

- Joseph John Gerry (1988–2004)

- Richard Joseph Malone (2004–2012), appointed Bishop of Buffalo

- Robert Deeley (2014–2024)

- James T. Ruggieri (2024-)

Auxiliary bishops

edit- Daniel Joseph Feeney (1946–1955), appointed Bishop of Portland

- Edward Cornelius O'Leary (1970–1974), appointed Bishop of Portland

- Amédée Wilfrid Proulx (1975–1993)

- Michael Richard Cote (1995–2003), appointed Bishop of Norwich

Other diocesan priest who became bishop

editDenis Mary Bradley, appointed Bishop of Manchester in 1884

Parishes

editThe Diocese of Portland is currently divided into 30 Clusters/Parishes.[44]

Notable churches

editCathedral

editBasilica

editThe Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul is located in Lewiston. The parish traces its roots to 1872 and grew due to a wave of late 19th century immigration by French Canadians. Construction of the current church began in 1906 and continued until 1936, by which time it was the second largest church in New England.

Construction languished because the diocese split the parish in 1905 and 1923 and the new congregations took a portion of the parish treasury to establish and construct their own churches. In 1983, the church was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 2004, Pope Benedict XVI named the church a minor basilica.

Historic places

editSt. John The Evangelist Catholic Church is located in Bangor. John Bapst oversaw construction of the church beginning in 1855, and in 1973 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Education

editHigh schools

edit- Cheverus High School – Portland

- Saint Dominic Academy – Auburn

Public affairs

editOn January 6, 2000, the Associated Press reported that the Diocese of Portland had negotiated with and supported a Maine lawmakers' bill that barred discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation; this bill aimed to overcome the results of the Maine election in February 1998 that repealed the gay marriage law that Maine Governor Angus King signed into law. The diocese did not have a position on the February 1998 vote, citing ambiguities in the law while acknowledging discrimination as unjust.[45][46]

In November 2009 it was reported that the Diocese of Portland had contributed $550,000, or 20% of the total cash contributed to Stand For Marriage Maine, a successful campaign to prevent then-impending legalization of same-sex marriage in Maine.[47][48] Roughly 55% of the funds donated by the Diocese came from other out-of-state dioceses who donated money to the Diocese of Portland's PAC.[49]

Ecclesiastical province

editSee also

edit- Catholic Church by country

- Catholic Church in the United States

- Ecclesiastical Province of Boston

- Global organisation of the Catholic Church

- List of Roman Catholic archdioceses (by country and continent)

- List of Roman Catholic dioceses (alphabetical) (including archdioceses)

- List of Roman Catholic dioceses (structured view) (including archdioceses)

- List of the Catholic dioceses of the United States

References

edit- ^ "Congregational Membership Reports | US Religion". www.thearda.com. Retrieved 2024-01-25.

- ^ a b c "History". Diocese of Portland. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ "Our History". Archdiocese of Baltimore. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ "Freedom of Religion Comes to Boston | Archdiocese of Boston". www.bostoncatholic.org. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ Page on Archdiocese of Baltimore on Catholic Hierarchy web site.

- ^ Woodard, Colin. "Parallel 44: Origins of the Mass Effect", The Working Waterfront, August 31, 2010. [1] Archived May 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Woodard, Colin. The Lobster Coast: Rebels, Rusticators and the Forgotten Frontier (2004) Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-03324-3

- ^ "Maine History (Statehood)". www.maine.gov. Archived from the original on May 4, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ "St. Dominic's Church, Portland, ca. 1913". Maine Memory Network. Maine Historical Society.

- ^ "St. John's Church: A History and Appreciation: Produced on the Occasion of the Jubilee 2000". Bangor Public Library. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ "Boston (Archdiocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ^ "Springfield in Massachusetts (Diocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ^ a b c Hurst, Violet (November 19, 2021). "BISHOP HEALY WRITES TO ARCHBISHOP WILLIAMS FROM ROME". The Boston Pilot.

- ^ a b Foley, Albert S. (1969). Bishop Healy: Beloved Outcaste. New York: Arno Press. ISBN 9780405019258.

- ^ "Manchester (Diocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ^ "Most Rev. Louis S. Walsh, D.D." Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "History of the Portland Diocese". Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland.

- ^ '"Bishop Walsh Warns of Danger from Enkindling Religious Hatred Fires", Lewiston Daily Sun, Feb. 8, 1923, p. 1

- ^ "Portland in Oregon (Archdiocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ^ "Most Rev. John G. Murray, D.D." Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland.

- ^ a b "Most Rev. Joseph E. McCarthy". Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland.

- ^ a b "Most Rev. Peter L. Gerety, D.D." Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland.

- ^ "Most Rev. Edward C. O'Leary, D.D." Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ "Pope picks Bishop Robert Deeley to lead diocese in Maine". The Boston Globe. December 18, 2013. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- ^ "Rinunce e nomine, 13.02.2024" [Renunciations and appointments, 13.02.2024] (Press release) (in Italian). Holy See Press Office. February 13, 2024. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c Pfeiffer, Sacha (March 17, 2002). "Maine school struggles to deal with sex abuse issue". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Bodnar, Marissa (November 29, 2017). "Cheverus: Accusations against priest led to increased vigilance". Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ Marina Villaneuve / Associated Press (2018-09-24). "Ex-priest with Boston ties sent to prison again for child sexual abuse". The Patriot Ledger, Quincy, MA. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Writer, Megan GrayStaff (2018-09-24). "Ex-priest, Cheverus teacher goes to prison for sexually assaulting Freeport boy". Press Herald. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ "Ex-Coach Admits Abuse: Cheverus legend Charles Malia says he molested boys, by Peter Pochna, Portland Press Herald, March 4, 2000". www.bishop-accountability.org. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ^ "No Recent Sex Abuse Found in Malia Case, by Peter Pochna, Portland Press Herald, March 24, 2000". www.bishop-accountability.org. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ^ Staff Report (2016-08-15). "Portland Catholic Diocese settles with 6 sexual abuse victims for $1.2 million". Press Herald. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Staff Report (2016-08-15). "Portland Catholic Diocese settles with 6 sexual abuse victims for $1.2 million". Press Herald. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ "Rev. James P. Vallely". www.bishop-accountability.org. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ "Newly released list of priests accused of sex abuse includes 9 with Maine ties". Bangor Daily News. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ "Diocese of Portland launches abuse reporting system". WCSH. 15 August 2019. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ "Portland, Maine, Diocese Removes Two Priests Who Admitted Sex Abuse of Minors". Associated Press. 2015-03-25. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ a b McKiernan, Terry (2021-02-26). "Diocese of Portland ME - BishopAccountability.org". Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ Writer, Megan GrayStaff (2019-05-24). "Defrocked priest, 76, sentenced to spend 16 years in prison for sexually abusing boy in Maine". Press Herald. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ "Defrocked priest Ronald Paquin convicted of abusing another boy". Boston Herald. 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ "Maine's top court upholds defrocked priest's sex abuse convictions". Bangor Daily News. 2020-04-24. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ Writer, Matt ByrneStaff (2020-04-24). "Maine high court upholds sex crime convictions of defrocked priest". Press Herald. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ "Defrocked priest Ronald Paquin ordered to serve 16 years in Maine". www.boston.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ "Cluster Configurations". Diocese of Portland. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Catholic Diocese Supports Rights Proposal". Associated Press. January 6, 2000.

- ^ Meara, Emmet (November 8, 2000). "Failure looms for gay rights". Bangor Daily News. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- ^ Harrison, Judy (March 2, 2012). "Portland bishop says Catholic Church won't actively campaign against gay marriage". Bangor Daily News.

- ^ "Maine Ethics Commission Public Disclosure Site". Archived from the original on 2013-01-11. Retrieved 2016-03-03.

- ^ Cassels, Peter (November 10, 2009). "Analysis reveals Roman Catholic dioceses poured money into anti-marriage campaign in Maine". Edge Media Network.

External links

edit- Official website

- Catholic Hierarchy Profile of the Diocese of Portland

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.