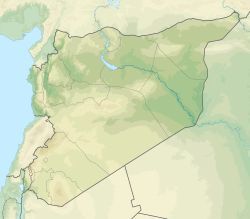

Deir ez-Zor (Arabic: دَيْرُ ٱلزَّوْرِ / دَيْرُ ٱلزُّور, romanized: Dayru z-Zawr / Dayru z-Zūr) is the largest city in eastern Syria and the seventh largest in the country. Located on the banks of the Euphrates River 450 km (280 mi) to the northeast of the capital Damascus, Deir ez-Zor is the capital of the Deir ez-Zor Governorate.[3] In the 2018 census, it had a population of 271,800.

Deir ez-Zor

دير الزور | |

|---|---|

City | |

Suspension bridge of Deir ez-Zor • Memorial of Armenian genocide Euphrates River • March 8 Square Panorama of Deir ez-Zor | |

| Coordinates: 35°20′N 40°9′E / 35.333°N 40.150°E | |

| Country | Syria |

| Governorate | Deir ez-Zor Governorate |

| District | Deir ez-Zor District |

| Subdistrict | Deir ez-Zor Subdistrict |

| Control | |

| Date of establishment | 3000 BC (old Deir Ezzour) |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Munhal Nader Hanawi[2] |

| • Mayor | Mohamed Ibrahim Samra |

| Elevation | 210 m (690 ft) |

| Population (2018 census) | |

• Total | 271,800[1] |

| Demonym(s) | Deiri Arabic: ديري, romanized: Dayri |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Area code(s) | Country code: 963 City code: 051 |

| Geocode | C5086 |

| Climate | BWh |

| International airport | Deir ez-Zor Airport |

| |

Etymology

editAd-Deir is a common shorthand for Deir ez-Zor. In the Syriac language of the Assyrian Christian population, Zeʿūrta (ܙܥܘܪܬܐ) means "little"; hence, Dīrā Zeʿūrta means "small habitation".[4] The current name, which has been extended to the surrounding region, indicates an ancient site for one of the Early Christian secluded Syriac monasteries established during the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire and Apostolic Age throughout Mesopotamia.[5] Although Deir (ܕܝܪܐ), which is Arabic (borrowed from Syriac) for "monastery", is believed to have been kept throughout the various Medieval and modern age renamings, Zor, which indicates the riverbank bush, appeared only in some late Ottoman records of the Deir ez-Zor Vilayet.[6]

Many different romanizations are used, including Deir Ezzor, Deir Al-Zor, Deir-al-Zour,[7] Dayr Al-Zawr, Der Ezzor, Deir Azzor, Der Zor, and Deirazzor.

History

editAncient history

editArchaeological findings in Deir ez-Zor indicate that the area has been inhabited since the ninth millennium BC. While the current location of the city has not always had a significant population, it was always an urban area, usually subordinate to more powerful Semitic cities, such as kingdoms like the Kingdom of Mari, which rose in the third millennium BC.[8]

During the third millennium BC, the Amorites settled the area and established the kingdom of Yamhad, one of whose urban centers was the city of Deir Ez-Zor (alongside Mayadeen, Qars, and Tarka and its capital of Aleppo). The city didn't suffer during the succession of major empires (such as the Akkadian Empire, Old Assyrian Empire, Babylonian Empire, Hittite Empire, Middle Assyrian Empire and Neo-Assyrian Empire) when some military campaigns by the emperors were destroying entire urban centers for fear of future rebellion, as Deir al-Zour was too small to be considered a threat, and the region was incorporated into Assyria during the Iron Age.[8]

In the third century BC, Alexander the Great crossed the region and built the city of Dura-Europos. Although influenced by Greek culture, the Semitic Aramaic language remained prevalent in the city. When Syria came under the Roman Empire in 64 BC, Deir Ez-Zor was a small, marginal village known as Azdra, which the Romans made the center of the region and founded a strong military garrison. Deir Ez-Zor came under the reign of Queen Zenobia of Palmyra in the third century, within an autonomous federation of the Roman Empire.[9]

Muslim conquest

editAfter the end of the Ridda wars in the Arabian Peninsula, Abu Bakr sent four armies to the Levant, led by Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan, Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah, Amr ibn al-Aas, and Shurahbil ibn Hasana. Because of the strength and size of the armies of the Byzantine Empire, Abu Bakr ordered Khalid ibn al-Walid to march with half of the Muslim Arab army to the Levant and command the armies there.

Khalid set off with his army towards Sham and opened Bosra and then defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Ajnadayn. After Umar ibn Al-Khattab became caliph in 13 AH (634 AD), Khalid was replaced by Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah. Abu Ubaidah was ordered to complete the conquest. He took Damascus, Baalbek, Homs, Hama and Latakia.

After the successive defeats of the Byzantine army, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius requested the help of the Assyrian Christians in Mesopotamia. They mobilized a large army and headed towards Homs, now the base of Abu Ubaidah in northern Syria, which they besieged. Heraclius also sent soldiers from Alexandria. Omar ibn al-Khattab wrote to Saad ibn Abi Waqqas to request support Abu Ubaidah with forces from Iraq, who were then organized under Iyad ibn Ghanm. When the Byzantines who were besieging Homs heard about the army coming from Iraq, they withdrew from Homs. Saad ordered Iyad to invade Upper Mesopotamia, which he conquered in 17 AH, including Deir Ez-Zor.

At the time, Deir Ez-Zor were adherents of Syriac Christianity and Judaism. There was a Christian monastery in Monastery of the Hermits, which became Omari Mosque. Many of the town's indigenous Christians left.[10]

During the Abbasid era, Deir Ez-Zor grew. The agriculture in the region prospered because of advances in irrigation. The small town, now called 'Deir Al-Rumman,' did not record any significant events during the decline of the Abbasid state and the ensuing Mamluk period until its destruction by the Mongols in the thirteenth century.[8]

Ottoman Era

editFirst Ottoman Era (1517–1864)

editThe first Ottoman era extended from the date the Ottomans entered Syria in 1517 until 1864, where the Ottomans found Deir Ez-Zor a small town on the upper Euphrates and chose it as a center for their employees and settled in some of tribal sheikhs to protect the trade route between Aleppo and Baghdad and The tribe members began to visit it to communicate the men of power and buy their needs.[8]

Some Arab and European travellers visited it and described its construction, economy, and the nature of its inhabitants. According to the description, "Its houses are adjacent over an artificial hill, and its inhabitants are strong, polite, and welcome guests. Their crops were wheat, barley, cotton, and corn, along with orchards full of fruit species, including palm trees, lemons, and oranges, the chess game is common among elders".[8]

Deir Ez-Zor has repeatedly been subjected to Bedouin attacks for looting and has been greatly affected by these attacks, including the attacks of Wahhabis in 1807; it was repeatedly plundered and destroyed by the Bedouin because the Ottoman Empire had not subdued them as it was preoccupied with its wars and the corruption of its sultans and officials. The city's people armed themselves with guns and organized a national army to defend the city resulting in the decline of the Bedouin attacks. Still, its negative effects were the shrinking of the city. Still, the isolation benefited the city's people because they relied on themselves to make many of their needs and those of neighboring villages, such as axes, spears, swords, gunpowder, and weaving cotton.[8]

When security was relatively stable, the commercial convoys started passing through the area, and Deir ez-Zor was a station for them, providing them with food, feed, and comfort. The khans were established in it, and the road between Aleppo and Baghdad began to revive it and get it out of isolation. Young people start traveling to Hauran with the beginning of the spring for trading or work and then return in the early fall; they also travel to Aleppo, Baghdad, Mardin and Urfa for trading.[8]

In 1831 Ibrahim Pasha took over Deir ez-Zor and annexed it to Hama Sanjak and appointed Maejun Agha governor of the city, Egyptian rule remained until 1840 when the authority of the Ottoman returned to the city, Perhaps the most prominent feature of Ibrahim Pasha's rule is the proliferation of weapons among the city's inhabitants, especially rifles, known as "Brahimiyat," which constituted a major tool to defend the city and repel Bedouin attacks.[11]

Second Ottoman Era (1864–1918)

editZor Sanjak

editOn 2 January 1858, the Ottoman government launched a military campaign under the command of Omar Pasha (Croatian) consisting of 500 soldiers to subdue the tribes in the Euphrates region. The campaign reached Deir Ez-Zor city and fought against the city's residents, where 16 Ottoman soldiers were killed. After the Ottoman army subdued the city, Omar Pasha recruited 16 young men from the city to replace the Ottoman soldiers killed.[12]

In 1864 the city revolted against Ottoman rule, and Soraya Pasha, the governor of Aleppo, sent a military force to suppress it. After the campaign, Soraya Pasha came to Deir ez-Zor He made it the center of the district's headquarters (Qaimakamiyya), and he returned to Aleppo after appointing Omar Pasha governor, whose rule did not last more than 6 months. Khalil Bey Saqib was appointed as Kaymakam of Deir ez-Zor after it was annexed to Aleppo.

During his reign, it established the government house (Dar Al Saraya), a military barracks, a hospital and some trade markets. Some of the arrivals from Urfa settled in the city to help Khalil Bey Saqib with the administration, as well as starting campaigns to settle the Bedouin in urban centers on the Euphrates.[13]

In 1868, the Qaimakamiyya was transformed to the Zor Sanjak, which did not report to the wali but reported directly to the Grand Vizier in Istanbul. Its ruler (Mutasarrıf) was granted wide powers and its area was extended to include the city of Raqqa and Hasakah.[12]

The rulers (Mutasarrıfs) solidified security, especially during Arslan Pasha's reign, and were interested in organizing and planning the city, building schools and streets and established the first public park. They also built bridges on the Euphrates and some mosques and encouraged afforestation and they used boats to cross the Euphrates. They reformed the tax system and introduced European uniforms into the city and did not generalize it.

The era of the Zor Sanjak lasted 54 years, where 29 Mutasarrıfs successively ruled it, the most recent being Hilmi Bey, who left the city with the Ottoman army on 6 November 1918. The continuous change of rulers (Mutasarrıfs) and lack of resources and disruption of conditions in the Ottoman Empire affected negatively on the urban, economic, cultural and social activity of the city. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought calamities, with many young people being recruited, famine and disease spread, livelihoods were confiscated, trade stopped and agriculture declined. But in the opinion of historian Abdul Qadir Ayyash, Deir ez-Zor owed its civilization to the Ottoman rulers despite their mistakes.[12]

Armenian genocide

editAt the beginning of World War I in 1914, the Ottoman Empire began systematic campaigns to kill and displace Armenians. Beginning April 1915, this was carried out through massacres, forced deportations, and displacement, which were marches under harsh conditions designed to lead to the death of the deportees. Researchers estimate the number of Armenian victims as between 1 million and 1.5 million.[14][15]

Deir ez-Zor was the last destination of the forced displacement of Armenian convoys and the scene of killings and slaughter by the Turkish gendarmerie, where the Ottoman authorities planned to exterminate Armenians. These plans failed because the people of Deir ez-Zor regretted what happened to the Armenian men, women, and children, prompting the mayor Haj Fadel Al-Aboud to help protect them and provide them with food, housing, safety and livelihoods.[16][17]

Despite Armenians coming to the region as part of death marches, the liberation that they achieved ultimately benefited the city, increasing population and growth rates. Historically, the city of Deir ez-Zor has been a special place for Armenians in Syria and the Armenian Diaspora. The Armenian genocide Memorial Church, which was officially built in 1991, includes a museum containing some remains, collectibles and maps for memory of the martyrs who died in that area by the Ottoman Turks. The city later became a pilgrimage destination for hundreds of thousands of Armenians on 24 April each year, after being declared in 2002 by Catholicos Aram I of the Armenian Orthodox of Cilicia as a pilgrimage to the Armenians.[18][19]

Post World War I

editFirst government of Haj Fadel

editTrouble broke out in the city of Deir al-Zour after the Ottomans left on 6 November 1918, where people began looting and stealing from each other across the area, so it was necessary to have a strong authority for protecting the city and its people and that led Al-Hassan who was the mayor to form his first government in the city and asking all tribal leaders in the villages and surrounding districts to support him and pledge allegiance to him. One of the priorities of this government was maintain the security and running the affairs of the city. This government later known as the "Haj Fadel Government".[20][21][22]

The government continued until the arrival of Sharif Nasser, the cousin of prince Faisal Bin Al-Hussein, on 1 December 1918, and Mar'i Pasha al-Mallah on 7 December 1918.[23]

British period

editOn 11 January 1919, the British army occupied the city via the Iraqi border and annexed it to Iraqi territory. The British government took care of the security and cleanliness of the city and set up a primary school that started teaching English. Fadel Al-Aboud remained mayor, During this period, Fadel Al-Aboud and a number of leaders of the Baggara tribe, Agedat and other tribes represented the Euphrates region at the Syrian National Congress held in late June 1919 Which declared on 8 March 1920 the independence of Syria and establishment of Arab Kingdom of Syria and the appointment of Faisal Ibn Al-Sharif Hussein as King.[24][25]

The people of Deir ez-Zor sought to get rid of British rule and wrote their wish to the Arab government in Damascus, The Iraqi officers of the Iraqi "Al-'Ahd Party" in Damascus wanted to occupy Deir ez-Zor to make it a base to liberate Iraq from the British occupation. So they appointed Ramadan al-Shallash as governor of Raqqa to be a step to liberate Deir ez-Zor, Officer Ramadan al-Shallash came and occupied Deir ez-Zor with the help of her people and "Albu Saraya" clan, and British troops withdrew on 27 December 1919 to the Iraqi border.[26]

Second government of Haj Fadel

editOn 27 December 1919, Ramadan al-Shallash took over the administration of Deir Ez-Zor as a military ruler, and his authority was nominal and the real ruling was to the city's notables, and they were not satisfied with his actions. Hence, they took him out of the city after two months.[27]

After the Battle of Maysalun on 24 July 1920 and occupation of Damascus by the French forces, the city of Deir ez-Zor was in a state of chaos and insecurity, which prompted Al-Hassan to form his second government, Which has done great services in protecting the city and maintaining the security of its people despite its limited capabilities. This government continued its work until 23 November 1920, when it was dissolved by a decision of the French occupation authorities.[28][29]

King Faisal left Syria for Hauran then Haifa and from there to Como in Italy then to London in October 1920 at the invitation of the British royal family, Upon his departure, the monarchy in Syria ended and began the French Mandate era.

French Mandate

editIn July 1920, French General Henri Gouraud issued an ultimatum to the government of King Faisal, known as the "Gouraud ultimatum ", he set four days to accept it.

Although the Syrian government accepted the ultimatum and accepted the demands of General Gouraud to demobilize the Syrian army and withdraw the soldiers from the mounds of the village of Majdal Anjar in violation of the decision of the Syrian National Congress, on 24 July 1920, French troops began to march on the orders of General Goubeier (By order of General Gouraud) towards Damascus, While the Syrian army stationed on the border was retreating, and when General Gouraud asked about this matter, replied that Faisal's message by accepting the ultimatum had reached him after the deadline.

on 24 July 1920, the Battle of Maysalun ended with the loss of the Syrian army and the death of the Minister of War Yusuf al-'Azma, After its control over the entire Syrian territory, France resorted to the fragmentation of Syria into several independent states or entities:

- State of Damascus (1920).

- State of Aleppo (1920).

- Alawite State (1920).

- The State of Greater Lebanon (1920).

- Jabal Druze State (1921).

- Sanjak of Alexandretta (1921).

The city of Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa and Al-Hasakah were followed to Aleppo.

When the French colonial forces entered Deir Ez-Zor on 9 November 1921, the region was locally ruled by Fadel Al-Aboud, a member of an aristocratic family; after a while, protests and demonstrations against occupation broke out, A group of French armored vehicles and dozens of soldiers encircled the house of Fadel Al-Aboud, where he was arrested and transferred to the military airport of Deir al-Zour and then transported by military aircraft to Aleppo, where he was imprisoned in the castle and during his imprisonment he met with the leader Ibrahim Hanano, In June 1922 he was released and returned to Deir Ez-Zor.[30][29]

Later, Fadel Al-Aboud was sentenced to exile to the city of Jisr al-Shughour after he was accused of preparing a revolt against French colonialism in protest against the military campaign by the French army against the Bukhabur tribes that refused to pay taxes to the French colonizer, and insulting Wali Deir al-Zour Khalil Isaac, who was cooperating with the French.[31][32][33][30]

In June 1922, under the pressure of the Syrian people and the continued demonstration, Gouraud declared the creation of a Syrian federation on a federal basis between Damascus, Aleppo, and Alawite state, provided that the Federation should have a president elected for one non-renewable year, The council of the Federation held its first meeting in June 1922 in the city of Aleppo and issued resolution No. / 1 / to form the Federal Government, Subhi Barakat, who is close to the French colonial authorities, was elected president of the federation.

The struggle against the Mandate

editThere were contacts between the leaders of the Great Syrian Revolution and some patriots of Syrian east area as Mohammed Al-Ayyash, who met in Damascus with Dr. Abdul Rahman Shahbandar, leader of the People's Party, and discussed with him the issue of extending the revolution to the Euphrates region and opened a front against the French to disperse their forces, and ease the pressure on the rebels of Ghouta and Jabal al-Arab, after returned Al-Ayyash from Damascus he started to arouse the enthusiasm of the people of Deir ez-Zor and invite them to fight, and agreed with his brother Mahmoud to go to the villages of the Albu Saraya clan that living west of Deir ez-Zor and which have a strong friendship with his father Ayyash Al-Haj, to form revolutionary groups with them to strike the French forces.[34][35][36]

Al-Ayyash managed to form a revolutionary group of thirteen armed men who were ready to take any military action against the French forces, They are:[37][38][39][34]

- Mahmoud Al-Ayyash

- Hakami Al-Abed Al-Salameh (Al-Shumaitiya village).

- Aziz Al-Ali Al-Salamah (Al-Shumaitiya village).

- Haji Ali Al-Abed Al-Salama (Al-Shumaitiya village).

- Hassan Al-Abed Al-Salamah (Al-Shumaitiya village).

- Hamza Al-Abed Al-Salama (Al-Shumaitiya village).

- Aslibi Masoud Al-Abdul Jalil (Al-Shumaitiya village).

- Khaleef Al-Hassan Al-Muhammad (Al-Kuraitia village).

- Lions of Hamdan (Al-Kuraitia village).

- Ahmed Al-Hassan (Al-Kuraitia village).

- Hameed Al-Sultan (Al-Kuraitia village).

- Abdullah Al-Khalaf Ibrahim (Deir ez-Zor city).

- Hamad Bin Rdaini – Al-Baggara tribe.

Some Syrians working with the French at translation centers, and others were secretly at the service of the revolutionaries and reporting news and information to Mohammed ِAl-Ayyash about the situation and movements of the French and their activities and the timing of their military operations. This helped Al-Ayyash guides the revolutionaries to strike the French forces.

In early June 1925, the translators informed Mohammed Al-Ayyash that a military vehicle carrying four French officers from France to inspect the French military construction departments in Syria and Lebanon would leave accompanied by their French driver Deir Ez-Zor on its way to Aleppo. He instructed his brother Mahmoud to set up an ambush in Ain Albu Gomaa on the road between Deir Ez-Zor and Al-Raqqa, where the highway runs through a profound valley and has a narrow stone bridge.[22][35][36][34]

If each of the criminals who committed this terrible offense deserves dying once, the gang leader Mohammed ِAl-Ayyash deserves hanging twice.

When the military vehicle arrived, the revolutionaries attacked and arrested the officers and took them with their car after they took their weapons to a desert called "Al-Aksiyya", and threw them with their driver in one of the abandoned wells where they died.[40][41][42]

The French were incensed for losing contact with their officers and began an extensive campaign including planes to search for them and when they found their bodies and inquired from the informants about the names of the revolutionaries, they sent a large military force equipped with heavy guns and planes to attack the Albu Saraya clan and blockade it.

French planes began bombing the clan villages with a devastating bombardment where the houses were destroyed, as were children and women and killed. Livestock was destroyed, as well as farms and crops. Civilians were killed, among them "Hanash Al-Mousa Al-Ani," "Ali Al-Najras," and a pregnant woman, and many were wounded by bullets and shrapnel from Airplane bombs. All of this was to pressure the people to surrender the revolutionaries.

When the French realised that the bombing did not convince the local people to give up the revolutionaries, they threatened to arrest the women of the revolutionaries, their mothers and sisters until the revolutionaries surrender themselves to the French, when the news arrived to the revolutionaries, they emerged from their hideouts and surrendered themselves to avoid arresting their women.[43][44]

The revolutionaries were tried in Aleppo, where The family of Ayyash Al-Haj appointed lawyer Fathallah Al-Saqqal to defend her; the court heard (officer Bono) head of the French intelligence in Deir Ez-Zor, who said: If each of the criminals, who committed this terrible offense deserve dying once, the gang leader Mohammed Al-Ayyash is deserving hanging twice.[40][41][42]

The French High Commissioner in Beirut, Maurice Sarrail, issued Decision No. 49S / 5 in August 1925, which ordered the exile of all members of the Ayyash Al-Haj family to the city of Jableh, Mahmoud ِAl-Ayyash and 12 of his companions were sentenced to death. The execution was carried out by firing squad on 15 September 1925 in the city of Aleppo. Mohammed ِAl-Ayyash was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment on the island of Arwad in Tartous city.[45]

Shortly after Ayyash Al-Haj family's living in Jableh, the French authorities assassinated Ayyash Al-Haj in a café outside the city by poisoning his coffee, and prevented the transfer of his body to Deir Ez-Zor city for reasons of public security, He was buried in Jableh in the cemetery of Sultan Ibrahim ibn Adham Mosque where the absent prayers held for the spirit of this martyr mujahid in all the Syrian cities.[40][41][42]

Independence

editThe city was neglected during the reign of the first Syrian republic and illiteracy was rampant by 95%. However, some achievements belonged to that stage, such as building the suspension bridge and the establishment of the first bank in addition to the palace of justice, the national library, the city museum, and the municipal stadium; during this period, literary and cultural clubs increased, electricity existed, and cafes became widespread.

The city participated vigorously in the sixtieth strike in 1936 and saw a large march on 10 February 1936; this strike led to the signing of the independence agreement between Syria and France and the arrival of the national bloc to power after parliamentary elections held at the end of the year in which three deputies represented the city.[46]

In 1941, the twenty-fifth government was formed in the modern history of Syria and the tenth in the era of the first Syrian Republic. The first after Taj al-Din al-Hassani became president. which gathered the various pillars of politics in Syria, during which the independence of Syria was proclaimed. The federal rule recognized the financial and administrative independence of Lattakia and Sweida. In this government, Mohammad Bey al-Ayesh took over the Ministry of National Economy to be the first minister from Deir ez-Zor and the Eastern Province. after his tenure, it dedicated the tradition of allocating a ministerial seat to a bourgeoisie in Deir Ez-Zor in successive Syrian Governments. And in the same year (1941), British-led forces defeated the Vichy French during the Syria–Lebanon campaign, which included a battle over Deir ez-Zor. They handed administration of the region to the Free French.[46][47]

The city has maintained its struggle and political role in addition to its civil activity even during the independence phase; in 1946, the wheat uprising against Governor Makram al-Atassi began due to the monopoly of the authority with the good wheat in the city, and the people succeeded in obtaining their rights.

In 1952 cotton cultivation was widespread, and automated pumping engines were introduced, which increased the area of arable land and cotton became the first crop of the city instead of wheat. The discovery of oil and salt during the reign of the second Syrian republic near the city helped to develop and expand urbanization and the increase the number of public and private companies that working in it, as well as increasing migration from the countryside towards it.[48]

Civil war

editProtests (2011–2012)

editDeir ez-Zor was one of the first cities that saw large demonstrations at the start of the Syrian civil war. The demonstrations began in the city on 15 March 2011, which was the first day in the movement of protests demanding the overthrow of the Syrian government. On 15 April 2011, a large demonstration was launched from the city's stadium despite the using of live bullets by the security forces and the militias supporting it.[49][50]

In the demonstrations on Friday, 22 April 2011 (the sixth Friday in the history of the Syrian revolution), the statue of Basil al-Assad was shot down, until then, the Syrian government had been cautious about the protests in Deir ez-Zor, because of their clan nature and the size of their area and the presence of quantities of weapons in it stored from the days of the Iraq war. When the demonstrators headed towards the statue of Basil al-Assad, the riot police fired only in the air. It is said that the demonstrators were not shot and prevented from dropping the statue because the security commanders did not know or appreciate the reaction that the people of the city could issue if one of the demonstrators were killed.[51]

Syrian security forces took complete control of the city in August 2011, but the Free Syrian Army (associated with the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces) returned to take control in June 2012.

Partial ISIS takeover (2014–2017)

editBy the beginning of 2014, ISIS announced the annexation of the city after ousting the FSA and a detachment of Syrian Armed Forces remained besieged in a small section of Deir Ez-Zor.[52] The Deir Ez Zor district remained one of the few Syrian Government strongholds in eastern Syria for more than two years.

ISIS militants launched an offensive in May 2015, capturing Palmyra and cutting off the remaining supply line to Deir ez-Zor.[53] The city was then effectively under siege by ISIS, leaving supplies to be solely delivered by transport helicopters.[53] ISIS attempted to stop the supplies by daily attacking the Deir Ez-Zor Airbase. However, their attempts failed due to the presence of the elite Republican Guards of the 104th Airborne Brigade led by Brigadier General Issam Zahreddine.[53]

From 10 April 2016 to 31 August 2017, the World Food Programme supplied the city with food and essential relief items through a high-altitude airdrop service. With a Russian contracted Il-76 aircraft and parachute systems provided by Canada, the US, and Russia, a total of 8015 pallets with an average weight of 754 kg were dropped into the besieged city of Deir-Ez-Zor. Three hundred nine flights were performed during the operational period.

Assad government control (2017–2024)

editIn early September 2017, the Syrian Arab Army, moving from al-Sukhnah, reached the stronghold and joined the besieged garrison. Shortly after that, the siege of both the city as well as the city's airport were lifted.[54][55] By 3 November 2017, the SAA had fully recaptured the city.[56] Concurrently with its operations to capture Deir ez-Zor, the Syrian Army launched a campaign to secure the whole western bank of the Euphrates, which ended on 17 December 2017.

From 8 September 2017 to 23 March 2019, a military operation east of the Euphrates River led by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the CJTF–OIR took place against the last bastion of the Islamic State in Syria. The campaign ended with a decisive victory for the SDF and its allies, and resulted in the capture of all of ISIL territory in the Deir ez-Zor Governorate after the Battle of Baghuz Fawqani.

In December 2022, oil workers were killed by ISIS.[57] In late August 2023, multiple skirmishes took place between SDF fighters and local Arab tribes which left dozens killed.[58] On 6 December 2024, pro-government forces withdrew from the city during the Deir ez-Zor offensive.[59] Subsequently, the Syrian Democratic Forces captured the city.[60]

Following clashes between rebel forces under the Military Operations Command and the SDF, the city ended up in the hands of rebel forces after the SDF withdrew on 11 December 2024.[61]

Economy

editThe city and its rural surrounding is a fertile and prosperous farming area, with livestock-breeding (for awassi sheep), cereals and cotton crops. Many agribusiness institutions work there as well.

Since the discovery of light crude petroleum in the Syrian desert it has become a centre for the country's petroleum extraction industry.[62] It is also a minor centre for tourism with many tourist facilities such as traditional French-style riverbank restaurants, up to 5-star hotels, a hub for trans-desert travel and an airport (IATA code: DEZ) in Al-Jafra suburb. There are salt mines nearby.

Culture

editThe majority of Deiries (from Deir ez-Zor) are Arab Muslims, with a few Armenian and Assyrian/Syriac families.

Deir ez-Zor was the final concentration place for Deir ez-Zor Camps for annihilating the Armenian deportation caravans. Tens of thousands of surviving men, women and children were systematically killed on the banks of the Euphrates River. The Armenian genocide Memorial Church commemorated the memory of Genocide victims who lost their lives, but it was destroyed on 21 September 2014 by ISIS.

Successive waves of new settlers from surrounding countrysides and provinces were heavily related to severe drought in late 1950s and 1990s most of them looking for standard jobs and giving up their farming and herding lifestyle. The Mesopotamian variety of Arabic is used in the city; a slight influence of the Aleppo dialect can be noticed as well. Dominated by Sunni Muslims, Christianity in Deir ez-Zor can be traced back to the Apostolic Age, with few active churches and chapels belong to different congregations.

The city was also famous for the Deir ez-Zor suspension bridge (Arabic: الجسر المعلق) which spanned the Euphrates[3] and was destroyed in 2013 during the civil war. The Deir ez-Zor Museum keeps thousands of antiquities collected from nearby archaeological sites in Northern Mesopotamia.

Main campuses of Al-Furat University and Aljazeera University are also located there.[63] Many other polytechnic schools and professional institutes provide tertiary education are based in the city as well.

The local daily newspaper Al Furat and few other publications are published there and circulated in neighbouring Al-Hasakah and Raqqa governorates.

International relations

editDeir ez-Zor is home to the third Armenian diplomatic mission in Syria; the Honorary Consulate of Armenia, opened on 11 February 2010.[64]

Deir ez-Zor Airport is an under-developed domestic and international terminal and important hub mostly connecting with Damascus and destinations in the Persian Gulf region.

Twin cities

editClimate

editKöppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies it as hot desert (BWh).

| Climate data for Deir Ez-Zor (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–1978) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.5 (72.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

32.7 (90.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

41.6 (106.9) |

44.2 (111.6) |

47.5 (117.5) |

47.8 (118.0) |

43.0 (109.4) |

41.0 (105.8) |

31.5 (88.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

47.8 (118.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

32.5 (90.5) |

37.7 (99.9) |

40.6 (105.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

27.2 (80.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.8 (46.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

33.6 (92.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

22.9 (73.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

20.6 (69.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.8 (60.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

17.6 (63.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 28.1 (1.11) |

24.1 (0.95) |

27.8 (1.09) |

22.2 (0.87) |

8.6 (0.34) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.01) |

8.0 (0.31) |

12.4 (0.49) |

24.1 (0.95) |

155.8 (6.13) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.8 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 27.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 67 | 57 | 49 | 38 | 27 | 26 | 28 | 32 | 42 | 57 | 75 | 48 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 161.2 | 179.2 | 223.2 | 243.0 | 310.0 | 351.0 | 372.0 | 356.5 | 309.0 | 257.3 | 207.0 | 161.2 | 3,130.6 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 5.2 | 6.4 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 10.0 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 11.5 | 10.3 | 8.3 | 6.9 | 5.2 | 8.6 |

| Source 1: Deutscher Wetterdienst[66]Meteostat[67] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA(precipitation and sun 1961–1990)[68] | |||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Deir ez-Zor city population". Archived from the original on 31 July 2012.

- ^ "الرئيس الأسد يصدر مَراسيم بتعيين محافظين جدد لخمس محافظات" [President Al-Assad issues decrees appointing new governors for five governorates]. S a N A. SANA. 17 October 2024. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Syrian Ministry of Tourism (in Arabic)". Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- ^ R. Payne Smith, Thesaurus Syriacus, s.v. ܕܝܪܐ; ܙܥܘܪܬܐ

- ^ Moffett, S. H. (1992): A History of Christianity in Asia: Beginnings to 1500. Harper, San Francisco. ISBN 0-06-065779-0

- ^ Shaw, S. J. (1978): The Ottoman Census System and Population, 1831–1914. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 9: 325–338.

- ^ BBC TV World News (7 Dec 2015) – Deir-al-Zour is variant used by BBC News

- ^ a b c d e f g Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing and distribution. p. 148.

- ^ Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing and distribution. p. 149.

- ^ Nouri, Abdel Karim (1907). Deir Ezzor. Al-Mashreq Magazine. p. 38.

- ^ Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing and distribution. p. 150.

- ^ a b c Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing and distribution. p. 152.

- ^ Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing and distribution. p. 151.

- ^ "United Nations Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities". Armenian genocide. 2 July 1985.

- ^ Fuat Dündar (2011). "Pouring a People into the Desert:The "Definitive Solution" of the Unionists to the Armenian Question". In Ronald Grigor Suny; Fatma Muge Gocek; Norman M. Naimark (eds.). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0-19-978104-1.

- ^ "Armenians in Deir ez-Zor, Syria". khabararmani. 17 February 2015.

- ^ Hanna, Abdullah (9 March 2018). "How the Syrians narrated the Armenian tragedy in 1915 and dealt with it". Alaraby.

- ^ Al-Ahmed, Safwan (26 April 2014). "Deir Ezzor is free of Armenians in memory of their massacres". Orient.

- ^ "Der Zor, Syria, Armenian Genocide Monument and Memorial Complex". www.armenian-genocide.org.

- ^ Bukhapur revolution with dates and evidence، Website Al-Muhasan City.. Archived 10 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alayyash، Abdul Qader، Prepare: Walid al-Mashouh، Hadarat Wady Alfurat ،Al Ahali for printing publishing and distribution، First Edition، 1989، P 152..

- ^ a b Sabbagh, Rand (2017). "Deir Ezzor a city on the banks of paradise". Al-Quds Al-Arabi Newspaper. Vol. 8789. pp. 34–35.

- ^ "Alhaj Fadel Alaboud, An article published in Baggara tribe Web site, 30/03/2009". Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing and distribution. pp. 153–154.

- ^ Zidane, Rgda (1 January 2015). "First Arab government and dreams of independence". Alsouria. Archived from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing and distribution. p. 153.

- ^ Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing and distribution. p. 154.

- ^ Alayyash، Abdul Qader، Prepare: Walid al-Mashouh، Hadarat Wady Alfurat ،Al Ahali for printing publishing and distribution، First Edition، 1989، P 154..

- ^ a b Alshamary, Anwar, Biggest Baggara Tribe, Dar Almaref, Homs, 1996, Page: 363..

- ^ a b Fattouh, Issa, Abdul Qader Ayyash Researcher and Historian, Almarifa Magazine, Ministry of Culture in the Syrian Arab Republic, No 646, year 56, July 2017, p 155..

- ^ Alnigress، Mahmoud، Bo Jimaa Bottel، Furat newspaper، 2005..

- ^ Sabbagh, Rend, Deir al-Zour city on the banks of Paradise, Al Quds Al Arabi, Twenty-eighth year, 09/04/2017 number 8789, page 34..

- ^ Al-Saqal, Fathallah, wholesale execution, Manarat al-Furat magazine, 09/2009, p. 29..

- ^ a b c d Al-Shaheen, Mazen Mohammad Fayez (2009). History of Deir Ezzor Governorate. Syria – Deir ezzor: Dar Alturath. p. 753.

- ^ a b "Memoirs of Lawyer Fathallah Al-Saqqal". Al-Furat Magazine: 28. 2009.

- ^ a b Sheikh Khafaji, Ghassan (2018). "Abdelkader Ayyash in his folk museum". The Culture and Heritage of Deir Ezzor. Alt URL

- ^ Qaisar, Saab (2015). "Abdul Qader Ayash, Mirror of the Euphrates Valley". Al-Watan Newspaper. 2220: 10.

- ^ Alngers, Mahmoud (2005). "One of the epics of heroic martyrdom in the Euphrates Valley". Al-furat Newspaper.

- ^ Alarfi, Subhi (2008). "Denshway in Syria hero Mahmoud Ayyash". Manaraa Euphrates Magazine: 46.

- ^ a b c "Deir Ezzor in the Syrian National Social Party". Al-Benaa Newspaper. 2015.

- ^ a b c Fattouh, Issa (2017). "Abdul Qader Al-Ayyash Researcher and historian". Almarifa Magazine. 646: 153–159.

- ^ a b c Morshed, Faisal (2016). "Druze Unitarians and the Syrian Revolution". Sasapost. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Alt URL

- ^ "محمد العايش 1880 -1968". 7 October 2012 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Marzouq, Yasser (2012). "Mohammed Al-Ayesh". Syrianna Magazine. 55: 11.

- ^ Sheikh Khafaji, Ghassan (2019). Golden Biography – Deir ez-Zor Bride of the Euphrates and the Syrian island. Syria - Damascus: House of the Raslan Foundation for Printing. pp. 320–321. ISBN 9789933005962.

- ^ a b Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing, and distribution. p. 157.

- ^ Mackenzie, Compton (1951). Eastern Epic. London: Chatto & Windus. OCLC 1412578.P.122

- ^ Ayyash, Abdul Qader (1989). The civilization of the Euphrates Valley. Syria – Damascus: Ahali for printing, publishing and distribution. p. 161.

- ^ "Demonstration in Damascus demanding freedom". Aljazeera.net. 15 March 2011.

- ^ "Syria, security uses batons and gas to prevent a mass demonstration from reaching the center of Damascus". BBC Arabic. 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Demonstrations of "Freedom Prisoners Friday" start in several Syrian cities". France 24 Channel. 15 July 2011.

- ^ "Syria: "Dozens" killed in the army's invasion of Deir Ezzor and Houla". BBC Arabic. 7 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Chris Tomson (12 December 2015). "100,000 Civilians under ISIS Siege in Eastern Syria". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Syrian army breaks Isis' three-year-long siege of Deir Ezzor: Liberating the city will mean relief for its 70,000 residents as Isis, feeling the pressure, begins to conscript female fighters The Independent, 5 September 2017.

- ^ Syrian Army breaks ISIS' siege on Deir Ezzor Airport and Hrabesh and Tahtouh neighborhoods SANA, 9 September 2017.

- ^ Isil facing endgame after fall of last city in its caliphate The Telegraph, 3 November 2017.

- ^ "Eastern Syria attack kills at least 10 oil workers: State media". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "U.S. backed Kurdish-led forces in eastern Syria battle Arab tribal unrest". Yahoo News. 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Towards the capital Damascus.. Regime forces withdraw from several points in Deir Ezzor, Al-Mayadeen and Al-Bukamal" (in Arabic). SOHR. 6 December 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "US-backed Syrian Kurds seize eastern city of Deir el-Zor, sources say". Reuters. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "Syrian armed opposition takes control of Deir ez-Zor". Trend News Agency. 11 December 2024.

- ^ International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook. Petroleum Economist. Institute for the Study of War. Oil infrastructure across Syria and Iraq (map). in BBC News. (18 May 2015). "Battle for Iraq and Syria in maps". Retrieved 18 May 2015. BBC News website

- ^ Al Jazeera University Archived 2 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Jude.edu.sy. Retrieved on 29 October 2013.

- ^ Thawra news (in Arabic)

- ^ Al-Baath news (in Arabic) Archived 3 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Klimatafel von Deir Ezzor / Syrien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ "Deir Ezzor Climate : Temperature 1991-2020". Meteostat. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ "Deir Ezzor Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 26 April 2017.