Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev

On 10 November 1982, Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the third General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and the fifth leader of the Soviet Union, died at the age of 75 after suffering heart failure following years of serious ailments. His death was officially acknowledged on 11 November simultaneously by Soviet radio and television. Brezhnev was given a state funeral after three full days of national mourning, then buried in an individual tomb on Red Square at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis. Yuri Andropov, Brezhnev's eventual successor as general secretary, was chairman of the committee in charge of managing Brezhnev's funeral, held on 15 November 1982, five days after his death.

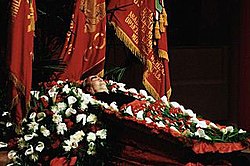

Body of Leonid Brezhnev, lying in state at the Pillar (Column) Hall of the House of the Unions | |

| Date | 10–15 November 1982 (42 years ago) |

|---|---|

| Location | Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Organized by | Yuri Andropov |

| Participants |

|

| Burial | Kremlin Wall Necropolis |

| Lying in state | Pillar (Column) Hall House of the Unions |

| Honor guard | Taman Division Kantemir Division |

| Funeral reception hosts | Yuri Andropov Nikolai Tikhonov Andrei Gromyko Vasili Kuznetsov |

The funeral was attended by forty‑seven heads and deputy heads of state, twenty‑three heads and deputy heads of government, forty heads of foreign government ministries, six leaders of foreign legislatures, and five princes. Most of the world's Communist party-led nations in 1982 were represented, while forty‑seven Communist parties from countries where the party was not in power also sent representatives. United States President Ronald Reagan sent Vice President George H. W. Bush. Eulogies were given by Yuri Andropov, Dmitry Ustinov, Anatoly Alexandrov, Viktor Pushkarev, and Alexei Gordienko.

Final year

editBrezhnev had suffered various cardiovascular ailments since 1974.[1] By 1982, the most deleterious of these had become arteriosclerosis of the aorta and cardiac ischemia and arhythmia,[2] all of which exacerbated by his heavy smoking,[3] obesity,[4] and dependence on tranquilizers and sleeping medication.[5][a]

Brezhnev previously broached the subject of his retirement with Yuri Andropov and Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko in 1979.[7] With no precedent or procedures existing for the voluntary retirement of a general secretary,[8][b] a majority of the Politburo instead preferred the stability provided by keeping the status quo and eschewing changes to the leadership[11] despite a minority view of the need for "a breath of fresh air".[12] With the Politburo's request that he remain, Brezhnev did not demur: "If you are all of this opinion, then I will keep working a little longer."[7]

The Politburo was nominally successful in keeping many of Brezhnev's ailments secret.[13] However, the decision to forgo retirement meant that by the beginning of 1982, a number of events began to more publicly illustrate the decline of Brezhnev's health, during what would be, his final year in office.

January–April, 1982

editAt Mikhail Suslov's funeral on 25 January 1982, Brezhnev "seemed confused" by elements of the ceremony, showing uncertainty over when to salute passing troops. While other Politburo members remained standing, Brezhnev was twice seen to move behind the Lenin Mausoleum parapet to sit in a chair and drink liquid from a mug.[14] Three weeks later, while attending the funeral of fellow Central Committee member Konstantin Grushevoi, Brezhnev was seen weeping profusely while offering sympathies to Grushevoi's widow—a scene broadcast uncensored—the first time Brezhnev was shown overcome with emotion on Soviet television.[15]

On 6 March 1982, while at Vnukovo airport to greet visiting Polish Prime Minister Wojciech Jaruzelski, Brezhnev's gait was shuffled and he appeared to be laboring for breath.[16] Four days later, on 10 March, Brezhnev met with President Mauno Koivisto of Finland.[17] At those meetings, as well as two days later at an International Women's Day gala at the Bolshoi Theatre, Brezhnev's health had noticeably improved. Brezhnev's visit to the Bolshoi was his fourth public appearance in five days.[16]

Tashkent factory accident

editOn 22 March 1982, Brezhnev began a visit to Soviet Central Asia which included a particularly rigorous schedule of "medal-giving ceremonies, speeches, and visits to industrial and agricultural enterprises".[18] On 25 March[19] while touring the Chkalov aircraft factory in Tashkent with Uzbek Communist Party first secretary Sharaf Rashidov, Brezhnev was injured when balustraded-catwalk scaffolding suddenly collapsed under the weight of a number of assembled factory workers, falling on top of Brezhnev and his security detail, giving Brezhnev a concussion and fracturing his right clavicle.[20] The subsequent secrecy surrounding this accident led Western journalists to speculate that Brezhnev had suffered a stroke, supposedly during his return flight from Tashkent, as there was no news footage of Brezhnev's arrival in Moscow after the 2,770-kilometre (1,720 mi) journey.[21][22] The lack of footage was an unusual breach of protocol on the part of the Soviet press, who invariably documented the top leadership arrivals after important functions abroad.[23] Upon landing at Moscow's Vnukovo airport, Brezhnev was removed from his Ilyushin Il-62 aircraft by stretcher and taken to the Kremlin Polyclinic[24] where, according to Western reports, he remained unconscious in a coma in critical condition for several days.[21][25] Brezhnev's injuries placed additional strain on an already precarious state of health,[26] a circumstance which contributed to a lengthened recovery time—his broken collarbone, for example—one injury which "subsequently refused to mend".[27]

Most of the engagements on Brezhnev's calendar, including a state visit by South Yemeni President Ali Nasser Mohammed, were cancelled in the immediate aftermath of the accident.[28] For the Soviet Foreign Ministry, the dual tasks of denying Brezhnev's injuries while explaining his conspicuous absences became a more complicated effort. The Ministry's initial response was to release a written statement on 5 April claiming Brezhnev was on a "routine winter vacation",[29] but their pronouncement did nothing to stem a growing speculation that Brezhnev had died as a result of his injuries.[30] In light of this, a fuller press conference was staged at the Academy of Sciences on 14 April, however, the choice of a substitute physician—Nikolay Nikolayovich Blokhin, in place of Brezhnev's cardiologist Evgeny Chazov—did little to stop the rumors, with Blokhin merely parroting the Foreign Ministry's earlier claim that Brezhnev was taking a "routine winter rest".[31]

In a further bid to project normalcy, on 16 April Defence Minister Ustinov gave the first public comments by a Politburo member since the accident when he presented an award to the city of Sochi while extolling Brezhnev's wartime record in a speech.[31][32] Two days later on 18 April, a proposal which had been sent to the Soviets earlier on 6 April by American President Ronald Reagan was utilized in a newer effort to negate the rumors of Brezhnev's death.[33] Reagan had invited Brezhnev to join him at an upcoming United Nations disarmament conference in New York in June, stating "I think it would be well if he and I had a talk."[34] The Politburo made use of this proposal to issue a counter-proposal of their own, wherein Brezhnev, in response to a staged question posed in Pravda, suggested meeting with Reagan in either Finland or Switzerland in October instead of June, the arbitrary date of October being set far enough into the future in the hopes that it might "dash domestic and foreign speculation on the Soviet leader's health and on his viability as a functioning leader".[35]

This motivation was noted by American ambassador to the Soviet Union Arthur Hartman, who held a meeting on 19 April with Soviet Minister of Culture Pyotr Demichev.[31] During the meeting Demichev emphasized the importance of a summit taking place irrespective of the October date Brezhnev's answer gave in Pravda, which contrasted with Soviet media emphasis on October rather than June. According to Hartman, the variance in dates was "additional indication that the public mention of October has the ulterior purpose of reassuring Soviet citizens that Brezhnev will still be around six months from now."[36] The rumors involving Brezhnev's death were not quashed until approximately four weeks after the accident, on 22 April 1982, when Brezhnev finally appeared in public looking "considerably thinner" at the Kremlin Palace of Congresses during celebrations marking the 112th anniversary of Lenin's birth.[37][38]

May–August, 1982

editBrezhnev's next public appearance was at the annual May Day festivities on 1 May 1982, where he stood on the balcony of Lenin's Mausoleum for the entire 90-minute parade, albeit displaying a demeanor which "confirmed earlier impressions of a man, for whom, public occasions were a strain."[39] On 23 May 1982, Brezhnev spoke at the Kremlin for 30 minutes in a slurred speech where he expressed approval of President Reagan's offer of new strategic arms negotiations.[40]

On 25 May, Brezhnev held meetings with Austrian President Rudolf Kirchschläger. The following day, 26 May, it was announced that Yuri Andropov had stepped down as head of the KGB after being appointed during a plenum meeting to a top position in the Communist Party Secretariat. Western analysts speculated that Andropov's move to the Secretariat strengthened his position among the other possible successors to Brezhnev, while noting that there was "no setback to the standing of Konstantin Chernenko", a fellow member of the Secretariat who, "by dint of his close association with Brezhnev" was "certain to figure in any succession struggle". Western analysts also stated that there was "no tangible sign of any diminution" in Brezhnev's control.[41] However, insiders to the 26 May meeting did observe that Brezhnev "could hardly walk" and needed to be "supported by a security guard disguised as an assistant". When Brezhnev attempted to climb a riser to another part of the stage, "he almost fell and the guard had to literally drag him" to his seat, where he sat for the rest of the meeting with a blank stare, in a condition likened to that of a "living mummy".[42]

In July, Brezhnev left Moscow for his usual summer vacation at a Black Sea retreat on the Crimean peninsula, where, in August, he was visited by Polish Prime Minister Jaruzelski, who updated Brezhnev with a "sobering account of continuing resistance" to martial law in Poland.[43]

September–October, 1982

editSeptember 1982 saw speculation from Soviet government sources on the topic of Brezhnev's retirement, when those sources suggested that Brezhnev might leave office with extraordinary honors, possibly in December 1982, about the time of celebrations for the 60th anniversary of the formal establishment of the Soviet Union in 1922. Western experts said that the reports of the impending resignation were possibly part of a campaign by Politburo members to either try to push Brezhnev out of office or to undercut the chances of Chernenko in any succession.[44]

Despite suggestions of retirement, the month of September 1982 saw the appearance of Brezhnev continuing to work. On 14 September, Brezhnev reaffirmed support for the Palestine Liberation Organization.[45] Remarks given on 16 September at a dinner for the visiting President of South Yemen, Ali Nasser Mohammed (rescheduled after the first visit was cancelled in the aftermath of Brezhnev's Tashkent accident) signaled Brezhnev's desire to allow the Soviet Union a greater role in any new Middle East peace process.[46] On 21 September Brezhnev met with Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in Moscow.[47] Although the prime minister spoke with Brezhnev regarding Indian concern over increasing influence on Pakistan from the United States and China,[48] she reportedly avoided other difficult discussions during their meetings, owing to Brezhnev's "shaky grasp of issues".[49]

The last week of September saw Brezhnev returning to Soviet Central Asia, with a visit to Baku, where he expressed a desire to strengthen Sino-Soviet relations in a speech given before the local Soviet leadership of Azerbaijan.[50] Brezhnev's speech in Baku was notable for an unusual moment of "levity and confusion" when, after mistakenly referring to Azerbaijan as 'Afghanistan', it became apparent that Brezhnev was reading from the wrong speech. When given the correct papers to read from, Brezhnev remarked that the mistake—while "not his fault"—would be fixed by him starting the speech again "from the beginning".[51]

On 28 October 1982, Brezhnev gave a speech to Soviet military leaders assembled at the Kremlin, where he pledged support for "a drive to increase the combat-readiness of the Soviet armed forces", and for an "upgrading of military technology" to counter the United States, which he described as threatening to "push the world into the flames of nuclear war". Brezhnev also re-emphasized the need for good relations with China, the fostering of which being described as "of no small importance".[52][53]

On 30 October 1982, Brezhnev exchanged his final correspondence with President Reagan, who had written ten days earlier regarding the condition of Soviet dissident Anatoly Shcharansky. Reagan had received word of a hunger strike that Shcharansky began on 27 September while imprisoned in Chistopol[54] and had sent Brezhnev a letter suggesting Shcharansky's release so that he could emigrate to Israel.[55] Brezhnev replied that because Shcharansky was a criminal in the eyes of Soviet jurisprudence, the matter "lies within the exclusive competence of the Soviet State" and that "there are neither legal nor any other grounds for resolving it in the manner you would wish."[56]

November final public appearance

editOn Sunday 7 November 1982, three days before he died, Brezhnev marked the 65th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution by attending the annual military parade through Red Square. Wearing tinted spectacles to guard against the sunlight and showing little animation, Brezhnev stood on the balcony of Lenin's Mausoleum along with other members of the Politburo for two hours in subfreezing temperatures as military regiments of troops and armored vehicles filed past.[57] In a speech at the Kremlin after the parade, Brezhnev remarked upon the Soviet Union's "essence of our policy" as "peaceableness" and spoke of the "sincere striving for equitable and fruitful cooperation with all who want such cooperation", while noting his "profound belief that exactly such a way will lead mankind to peace for the living and would-be generations."[58]

Death and declaration

editOn Monday 8 November 1982, Brezhnev spent the October Revolution's observed holiday hunting at Zavidovo.[59] On Tuesday 9 November, Brezhnev spent what was to be his last morning at his office in the Kremlin meeting with Andropov, working on documents, and speaking by telephone with Internal Affairs minister Nikolai Shchelokov.[8] Brezhnev then took his midday sleep. When he awoke he found his afternoon appointment with Tolya the barber cancelled by Brezhnev's bodyguard Medvedev, after the barber showed up to work severely inebriated.[c] Medvedev ended up styling Brezhnev's hair himself, and Brezhnev left the Kremlin at 19:30 MSK (UTC+3:00). Traveling in Brezhnev's ZiL limousine, Medvedev lit a cigarette "so Brezhnev could inhale [passively] the smoke".[61] Brezhnev retired to bed before the Tuesday evening newscast, his only complaint being that he "couldn't eat much".[59]

On the morning of Wednesday 10 November, Brezhnev's bodyguards found him "lying motionless in his bed".[59] A brief effort was made to resuscitate him until the cardiologist Chazov, whom Medvedev had summoned from the Kremlin Polyclinic, quickly determined that he had already been dead for several hours[62] after suffering heart failure.[63]

The first hint to the Soviet people that a death had occurred within the top leadership came Wednesday evening at 19:15 MSK on Channel 1, when a television program in honor of the "Day of the Militia Men" was replaced by a documentary on Vladimir Lenin.[64] At 21:00 MSK on the Soviet state television newscast Vremya (Время), the hosts wore somber clothes instead of their normally informal dress. An unscheduled program of war reminiscences aired after the newscast, while on Channel 2, an ice hockey game was replaced with a concert featuring Tchaikovsky's Pathétique symphony.[65]

At first, Soviet citizens believed it was Andrei Kirilenko who had died, as he had not been present at the 65th anniversary of the October Revolution a few days earlier[65] (he died in 1990).[66] Speculation that it was Brezhnev who had died began when it was noted that Brezhnev had failed to sign a message of greetings published by TASS to José Eduardo dos Santos, the Angolan president, on the occasion of Angola's Independence Day. In previous years the message was signed by Brezhnev, but on this occasion it was signed in the name of the Central Committee.[67]

Confirmation of Brezhnev's death was eventually made public on Thursday 11 November, simultaneously by Soviet radio and television hosts.[65] The television announcement was read at 11:00 MSK by Igor Kirillov in a distinctively somber style, with reverential pauses between statements of the "grievous loss" suffered by the Soviet people of an "outstanding politician and statesman of our time", along with Kirillov's reassurances that the party remained "capable of carrying out its historic mission".[68]

Condolences

editUpon news of Brezhnev's death, Syrian President Hafez al-Assad declared seven days of mourning.[69] Cuba and Laos declared four days of mourning; Nicaragua, Afghanistan, India, Vietnam, and Kampuchea all declared three days of mourning, while North Korea declared one day of mourning.[70][71] Argentina also declared one day of mourning—specifically for 15 November—while directing that the Argentine flag fly at half-mast for three days.[72]

Pope John Paul II promised "a particular thought for the memory of the illustrious departed one", while former West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt said Brezhnev's death would "be painfully felt". The government of the People's Republic of China expressed "deep condolences", while Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi said "he [Brezhnev] stood by us in our moment of need."[65]

In Tokyo, chief cabinet secretary Kiichi Miyazawa issued Japan's official statement describing Brezhnev's death as "a truly regretful event for the development of friendly relations", and offered condolences to "the bereft family and people of the Soviet Union".[73] French President François Mitterrand spoke of Brezhnev as "a great leader of the Soviet Union, a statesman whose eminent role in the world will be remembered by history", while Queen Elizabeth II's statement described how she "learned with regret of the death of President Brezhnev", and imparted "in my own name and on behalf of the British people ... our sympathy to you and the people of the Soviet Union."[74]

Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi remarked that Brezhnev tried all means to "achieve world peace".[75][dubious – discuss] On 12 November Guyanese president Forbes Burnham wrote a message in the Soviet embassy's condolence book in Georgetown, where he noted how the Soviet Union had lost "a leader and statesman whose consuming interest and self-imposed objective was a world where peace dominated."[76]

Speaking at a Veterans Day ceremony, American President Ronald Reagan called Brezhnev "one of the world's most important figures for nearly two decades" while expressing his hope for an improvement in Soviet–US relations.[77] Reagan then visited the Soviet embassy in Washington, D.C., on 13 November to sign a message in the embassy's condolence book.[78] Reagan later described having "a strange feeling in that place", noting how no one, except the ambassador, was smiling.[79] Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin noticed Reagan appearing "guarded and very inhibited when entering the embassy ... wondering what kind of place it was", but stated that Reagan seemed "more in his element by the end of his visit".[80]

Andropov's succession

editThe twenty-four hour delay in declaring the death of Brezhnev was later seen by First World commentators as proof of an ongoing power struggle in the Soviet leadership over who would succeed as general secretary. Prior to this, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko were both seen as equal candidates for the position.[57] When the announcement confirming Brezhnev's death was finally made, it stated that Yuri Andropov was elected chairman of the committee in charge of managing Brezhnev's funeral, suggesting Andropov had overtaken Chernenko as Brezhnev's most-likely successor.[65]

The Central Committee election confirming Andropov as general secretary took place on 12 November. The plenary meeting began with a speech by Andropov where he first eulogized Brezhnev, whose life "came to an end at a time when his thoughts and efforts were set on the solution of the major tasks of economic, social and cultural development laid down by the 26th Congress", then went on to address the meeting members who "met today to ensure the continuation of the cause to which he [Brezhnev] gave his life".[81] After recognizing a minute of silence in honor of Brezhnev, Chernenko took the floor to speak on the election. Chernenko in his speech quickly nominated Andropov to become general secretary, stating Andropov had "assimilated well, Brezhnev's style of leadership" while "possessing modesty ... respect for the opinion of other comrades, and passion for collective work".[82] The ensuing vote was unanimous in selecting Andropov to be the new general secretary.[83]

Funeral service

editThe Taman and Kantemir Guard divisions of the Moscow militsiya sealed off downtown Moscow on Friday 12 November.[84] Large avenues were tightly guarded by the police and the Moscow military garrison while soldiers, wearing black-edged red armbands, stood in front of the House of the Unions, the building itself decorated with numerous red flags and other communist symbols.[65]

Brezhnev's body lay in state within the Pillar, or Column Hall, of the House of the Unions for three full days, a period of mourning during which Soviet citizens, government officials, and various foreign dignitaries came to pay their respects and lay wreaths at the foot of Brezhnev's bier. Andropov and other members of the Politburo paid their respects to Brezhnev's family, including his widow Viktoria Brezhneva, daughter Galina Brezhneva, and son Yuri Brezhnev, who were all seated within a reception area adjacent to Brezhnev's bier.[85] Despite the Soviet state's official atheist status, Patriarch Pimen, Moscow patriarch and head of the Russian Orthodox Church, attended Brezhnev's lying in state along with three metropolitans and an archbishop. Pimen, who supported Soviet policies at home and abroad while keeping his ecclesiastical work "well within the bounds established by the state", also offered his condolences to Brezhnev's widow and daughter during his visit.[86]

On the day of the funeral itself, Monday 15 November, Brezhnev's coffin was placed on an artillery carriage and towed by an olive-green BRDM-2 armored vehicle of the Red Army in a procession to Lenin's Mausoleum on Red Square. At the head of the procession, a large portrait of Brezhnev was carried by members of the military[87] who, in turn, were followed by the members of Brezhnev's family, dozens of wreaths, and Brezhnev's military and civilian medals carried by Soviet colonels and other military officers.[88] During Soviet funerals, the deceased's medals are placed on pillows which later accompany the coffin in a procession to the gravesite.[89] As Brezhnev had more than two hundred medals, several had to be placed on each pillow. Brezhnev's medal escort ultimately comprised forty-four persons.[90]

In addition to the Soviet officials, foreign dignitaries and other VIP's gathered within the Red Square grandstand, a number of ordinary Soviet citizens were assembled in Red Square to act as a 'silent' audience. Due to concerns over the large number of dignitaries present, this rectangular space of citizens was surrounded by a two-chain security cordon of military and civilian officers, a cordon which did not break until the last of the dignitaries had left Red Square.[91]

Eulogies

editOnce the funeral procession arrived at Red Square, eulogies were given from the Lenin Mausoleum balcony by Andropov, defence minister Dmitry Ustinov, and by three representatives of the 'people': President of the Academy of Sciences Anatoly Alexandrov; factory worker of the Moscow Plant of Calculating and Analytical Machines, Viktor Viktorovich Pushkarev; and Alexei Fedorovich Gordienko, the first secretary of the Dneprodzerzhinsk City Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine,[92] the city where Brezhnev began his party work in 1937.[93]

Andropov's eulogy offered praise for Brezhnev's détente policy, where he "consistently fought, with all the ardor of his soul, for the relaxation of international tension, for delivering mankind from the threat of nuclear war", as well as praise for Brezhnev's "strengthening the cohesion of the socialist community and the unity of the international Communist movement".[94] Ustinov's eulogy similarly touched on Brezhnev's role as an "outstanding architect of détente" while mentioning Brezhnev's position as political commissar in the Soviet 18th Army during World War II, noting how Brezhnev led his men "with the fiery party word".[95] Anatoly Alexandrov's eulogy noted how Brezhnev "deeply and correctly assessed the necessary relationship between fundamental and applied research," with Brezhnev providing "great assistance in developing new areas of science" through the "creation of the energy base of the Soviet Union", and that by doing so, Brezhnev "achieved a manifold increase in the economic and defence power of our country".[96]

Pushkarev's eulogy commended Brezhnev for "how close to his heart he took the needs of the people, the instructions of the electors", while acknowledging "with what great warmth he treated every person with whom he had to meet". Gordienko's eulogy described Brezhnev as someone of "rare charm" who "closely connected with his native city, with our city party organization" where, for all his busy work, he still "found time and opportunity to delve into our affairs, supporting us with a warm word and fatherly advice." Gordienko called attention to the working people of Dneprodzerzhinsk and the entire Dnepropetrovsk region as "constantly feeling the attention and care of our beloved Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev", where his "warm, sincere conversations with fellow countrymen" left interlocutors with an understanding of Brezhnev's "deep interest in their life and work".[96]

Burial

editAfter the eulogies were delivered, a military orchestra played the third movement of Chopin's Sonata No. 2 as pallbearers led by Andropov and Nikolai Tikhonov carried the coffin to a grave site located just to the left of Yakov Sverdlov, an aide to Lenin, and to the right of Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder of the secret police.[97] Brezhnev's family then made their farewells, with his widow Viktoria and daughter Galina kissing Brezhnev on the face in accordance with Russian Orthodox traditions. As Brezhnev's body was lowered into the grave, tugboats on the Moscow River sounded their signal horns.[95] The Soviet national anthem was played along with the ceremonial firing of several volleys of artillery.[98] While gravediggers began to shovel the dirt, Brezhnev's family and colleagues immediately surrounding the grave carefully tossed in their own handfuls,[99] in accordance with Soviet funeral traditions.[100] The conclusion of the burial service featured a military parade with sailors in black uniforms, infantry troops in brown, border units in dark green and airmen in blue uniforms marching ten abreast through Red Square.[101]

Brezhnev's body reportedly sustained two falls before it was buried. The first occurred on 12 November when Brezhnev's body fell through the bottom of the coffin as it was being lifted into place on its catafalque at the lying in state in the House of the Unions. After that incident, a new, metal-plated coffin was made, and as it was being lowered into the grave on 15 November, the gravediggers could not handle its weight, and the coffin fell with a loud crash into the grave.[102] The second occurrence of Brezhnev's body being dropped is disputed by one of the gravediggers, Georgy Kovalenko, who in 1990 gave an account of the event in a Sobesednik supplement to Komsomolskaya Pravda, where he stated that he lowered Brezhnev's coffin "by the book ... quickly and gently as if by a high-speed elevator". Kovalenko stated that the sound resembling a crash that viewers heard on television during a live broadcast of the funeral was actually "the sound of the Kremlin clock and a cannon salute".[103]

Foreign delegations

editFollowing the burial service in Red Square, a funeral reception for attending delegations of foreign state dignitaries and Communist party representatives was held at the Kremlin in St. George's Hall, with the Soviet leadership's four ranking members present: General Secretary Andropov (as leader of the CPSU); acting President Vasili Kuznetsov (as interim head of state); Premier Tikhonov (as head of government); and Minister Gromyko (as head of foreign affairs).[97] Each foreign delegation stood in line in strict order, with the leaders of the Warsaw Pact and other Soviet satellite countries first, followed by leaders of foreign communist parties and finally, leaders and representatives of the remaining non‑Socialist countries.[104] A great number of foreign Communist Party delegations attended Brezhnev's funeral despite the International Department's attempts at limiting the dispersal of invitations. Not wanting the "small fry" to show up, the Department's intentions were thwarted when these smaller delegations simply bypassed the Department and went to the Soviet embassies located in their respective countries in order to "snatch" tickets themselves.[105]

British Foreign Secretary Francis Pym was unsuccessful in convincing Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to attend the funeral. Thatcher, whose relations with Pym were "frosty", had remained "skeptical of the idea that summit talks between the leaders of the two superpowers could do any good", and thus was "wary of closer contact with the Communist world".[106] Thatcher dismissed Pym as foreign secretary in 1983 and later agreed to attend the funerals of Andropov in 1984 and Chernenko in 1985.

Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau was lobbied by certain members of his government not to attend Brezhnev's funeral, in particular, by Canadian Ambassador to the United States Allan Gotlieb, who suggested strong domestic concerns from the Polish-Canadian diaspora over Soviet support of martial law in Poland merited sending Governor General Edward Schreyer instead.[107] Nevertheless, Trudeau decided to attend the main funeral service in Red Square and the lying in state in the House of the Unions with his 10-year-old son, future Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.[108] The funeral reception held in St. George's Hall, Pierre Trudeau attended alone.[109]

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi left Moscow immediately following the funeral reception in St. George's Hall in order to attend the funeral of Indian spiritual leader Vinoba Bhave, who had died earlier that day.[110]

Italy—at that time, the Western nation with the largest number of Communist Party members serving in the government—sent a delegation comprising five individuals, including President of the Italian Senate and former prime minister Amintore Fanfani; Foreign Minister Emilio Colombo; and three out of the 310 Communist Party members serving in the Italian legislature: Senator Paolo Bufalini; Chamber of Deputies member Giancarlo Pajetta; and fellow Chamber of Deputies member and Italian Communist Party general secretary, Enrico Berlinguer.[105]

Although invited, Albania was conspicuous for being the only Communist-led nation not to send a delegation to the funeral.[111]

American delegation

editAccording to President Reagan, the Soviets made a suggestion that any American delegation to the funeral should comprise no more than three people.[77] American Secretary of State George Shultz and National Security Advisor William Clark both tried to persuade Reagan to attend the funeral. Reagan however decided not to go, with administration officials giving the reason that Soviet and American leaders never made such gestures of attendance in the past, along with concern over the possibility of Reagan's attendance being seen as "hypocritical grandstanding" in light of his prior criticisms of the Soviets.[67] Reagan himself stated at a news conference that his decision not to attend was additionally influenced by a conflict in schedules, with his own schedule calling for "visits here by a head of state next week".[112] This was in reference to the forthcoming visit of Helmut Kohl, the interim chancellor of West Germany since the October 1982 collapse of Helmut Schmidt's Social Democratic government, whose first visit to the White House as chancellor was planned for Monday, 15 November 1982, the same day as Brezhnev's funeral.[113] Reagan also said that while "our goal is and will remain a search for peace" with the Soviets, he believed such searching could continue "without my attendance at the services".[112]

In place of his own attendance Reagan sent a delegation headed by Vice President Bush, who happened to be overseas conducting a seven-nation tour of Africa at the time.[114] After receiving word from Reagan redirecting him to the funeral, Bush flew from Lagos, Nigeria to Frankfurt, West Germany, where a majority of the aides and staff accompanying him on the African tour were disembarked to wait while Bush continued on to Moscow without them.[115] Upon his arrival at Sheremetyevo airport on 14 November, Bush and Second Lady Barbara Bush—along with Shultz, who had arrived earlier from Washington[116]—were taken to the House of the Unions where they were joined by American ambassador to the Soviet Union Arthur Hartman and the ambassador's wife Donna. As an orchestra inside the Pillar Hall played Åse's Death from Edvard Grieg's Peer Gynt, the five Americans made their way in procession towards the foot of Brezhnev's bier where they paid their respects by bowing their heads. When the group turned to leave, a Soviet protocol officer motioned them over to an area where the members of Brezhnev's family were seated, whereupon Brezhnev's widow, Viktoria, rose to greet Bush, who conveyed to her the "condolences of Reagan and the American people".[117]

Gus Hall, the longtime general secretary of the American Communist Party, attended Brezhnev's funeral separately from the American government's delegation.[118]

Actor Chuck Connors contacted White House Press Secretary Larry Speakes shortly after Brezhnev's death announcement, asking to be included with the American government's delegation travelling to Moscow. Connors was told of the limit of three representatives suggested by Soviet funeral officials, and that because of this, he could not be accommodated. Connors had met Brezhnev briefly in San Clemente, California, during Brezhnev's 1973 state visit.[119]

American businessman Armand Hammer, a close acquaintance of Brezhnev's, brought along his friend American film producer Jerry Weintraub to the funeral. Weintraub had previously mentioned in a telephone conversation with Vice President Bush that he [Weintraub] did not have an invitation and would not be attending. However, owing to his arrival in Moscow accompanied by Hammer, Weintraub was granted an invitation positioning him within a VIP section close to the Mausoleum, surprising Bush (seated farther away) who wondered after their earlier conversation how it was that he came to see Weintraub "not only at the funeral, but basically seated inside the coffin".[120] According to Weintraub, Bush complained that he and Shultz were seated "in the back, away from the cameras" because "the Russians did not want them to be seen on television".[121] While positioned farther away from the Mausoleum than Weintraub was, Bush was still seated from his perspective "very close to the front" (the first few rows of Red Square's grandstand) offering Bush a vantage point to the "goose-stepping, armswinging, elite guard marching in".[122]

Bush–Andropov meeting

editFollowing the funeral reception in St. George's Hall, Andropov and Foreign Minister Gromyko held a formal sit-down meeting with Bush, Shultz, and Hartman in one of the state reception rooms of the Kremlin palace.[123] The meeting was the highest level held between the Americans and the Soviets since the Carter–Brezhnev summit 3+1/2 years earlier.[124] During the meeting Andropov raised concerns regarding the United States, in particular, his belief that "due to US actions, at present almost the entire stock of stability between the two countries ... had been carelessly squandered."[125] Andropov criticized "American interference in internal Soviet affairs" just before moving to conclude his statement, at which point he issued an apology for assigning criticisms to the United States "on this, not the most auspicious occasion" where "he [Bush] and Secretary Shultz had come to Moscow to express condolences and sympathy to the Soviet Union at this moment of grief."[126] Bush's response lamented the lack of time which prevented him from either rebutting Andropov's contentions or "detailing the list of Soviet actions which we would consider hostile".[127] Bush went on to describe aspects of the funeral which drew his interest, such as "the young men who had marched in the parade at the ceremony today", a display which reminded him fondly of his own four sons (who were of similar age).[128] Bush also mentioned his hope that related US‑Soviet negotiations underway at that time in Geneva would continue to "bear fruit".[129]

After meeting with Andropov, Bush and Shultz were taken to the American embassy to meet with seven Pentecostals who had taken refuge inside and were living in the embassy since June 1978 after being denied exit visas from the Soviet Union. Bush and Shultz both expressed their hope that "the time will soon come when they can leave".[130] Bush was then taken to the airport where, after a brief stopover in Frankfurt to pick up his waiting aides and staff, he resumed his African tour by flying to Harare for a state visit of Zimbabwe.[131]

In his report on the funeral proceedings sent to Reagan by Bush while still aboard Air Force Two, Bush stated that Andropov "seemed sure of himself" and that "much of the rhetoric was predictable and accusatory."[132] Bush described the only moment of levity during the Andropov meeting as occurring when Andropov "smiled" at Bush's suggestion that they each had something in common, with Bush director of the CIA at the same time Andropov was in charge of the KGB.[133]

Shultz met with Reagan in the Oval Office upon returning to Washington to discuss the funeral visit. Shultz conceded that his initial instinct favoring Reagan's attendance at the funeral turned out to be wrong, and that Reagan "was right not to go".[134]

List of foreign dignitaries

editThe foreign dignitaries who attended Brezhnev's funeral:[135][136]

- Babrak Karmal · Afghan Revolutionary Council chairman

- Oliver Tambo · African National Congress president

- Mohamed Chérif Messaadia · Algerian National Liberation Front general secretary

- José Eduardo dos Santos · Angolan president

- Adnan Omran · Arab League assistant secretary general

- Julio Martínez Vivot · Argentine defence minister

- Zelman Cowen · Australian former governor-general

- Rudolf Kirchschläger · Austrian president

- Willibald Pahr · Austrian foreign minister

- Franz Muhri · Austrian Communist Party chairperson

- A. Mahmoud · Bahraini National Liberation Front representative

- M.H. Ali Khan · Bangladeshi transport & communications minister

- Manzurul Ahsan Khan · Bangladeshi Communist Party central committee secretary

- Wilfried Martens · Belgian prime minister

- Louis Van Geyt · Belgian Communist Party chairman

- Romain Vilon Guézo · Beninese National Revolutionary Assembly president

- Jorge Kolle Cueto · Bolivian Communist Party general secretary

- Samuel Akuna Mpuchane · Botswanan ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Sizinio Pontes Nogueira · Brazilian ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Todor Zhivkov · Bulgarian Communist Party general secretary and State Council chairman

- Grisha Filipov · Bulgarian premier

- Dimitar Zhulev · Bulgarian ambassador to the Soviet Union

- U Kyaw Khin · Burmese ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Emile Mworoha · Burundian National Assembly president

- Samuel Eboua · Cameroonian agriculture minister

- Pierre Trudeau · Canadian prime minister

- William Kashtan · Canadian Communist Party general secretary

- Abílio Duarte · Cape Verdean National Assembly president and foreign minister

- Luis Corvalán · Chilean Communist Party general secretary

- Huang Hua · Chinese State Councillor and foreign minister

- Ma Xusheng · Chinese foreign ministry's Soviet and East European department chief

- Wang Jinqing · Chinese foreign ministry official

- Yang Shouzheng · Chinese ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Héctor Cherry · Colombian permanent representative to the United Nations

- Manuel Cepeda Vargas · Colombian Communist Party representative

- Denis Sassou Nguesso · Congolese president

- Fidel Castro · Cuban president

- Carlos Rafael Rodríguez · Cuban vice president

- Ramiro Valdés Menéndez · Cuban vice president and interior minister

- Rene Anillo Capote · Cuban ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Spyros Kyprianou · Cypriot president

- Gustáv Husák · Czechoslovak president

- Lubomír Štrougal · Czechoslovak premier

- Vasiľ Biľak · Czechoslovak Communist Party central committee secretary

- Čestmír Lovětínský · Czechoslovak ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Prince Henrik · Danish crown representative

- Poul Schlüter · Danish prime minister

- Uffe Ellemann-Jensen · Danish foreign minister

- Jørgen Jensen · Danish Communist Party chairman

- Narciso Isa Conde · Dominican Communist Party general secretary

- Mamdouh Salem · Egyptian former prime minister

- Michel Kamel · Egyptian Communist Party general secretary

- Khaled Mohieddin · Egyptian National Progressive Union Party general secretary

- Mario Aguiñada Carranza · Salvadoran Communist Party central committee politburo member

- Mengistu Haile Mariam · Ethiopian Provisional Military Administrative Council chairman

- Mauno Koivisto · Finnish president

- Pär Stenbäck · Finnish foreign minister

- Jouko Kajanoja · Finnish labor minister and Communist Party chairman

- Pierre Mauroy · French prime minister

- Claude Cheysson · French foreign minister

- Maurice Faure · French National Assembly foreign affairs chairman

- Georges Marchais · French Communist Party general secretary

- Maxime Gremetz · French Communist Party official and former member of the National Assembly

- Erich Honecker · East German Socialist Unity Party general secretary and State Council chairman

- Willi Stoph · East German premier

- Horst Sindermann · East German Volkskammer president

- Gerald Götting · East German State Council deputy chairman

- Günter Mittag · East German Socialist Unity Party economic minister

- Karl Carstens · West German president

- Hans-Dietrich Genscher · West German vice chancellor and foreign minister

- Herbert Mies · West German Communist Party chairman

- Horst Schmitt · West Berliner Socialist Unity Party chairman

- Andreas Papandreou · Greek prime minister

- Dimitris Maroudas · Greek deputy prime minister

- Karolos Papoulias · Greek deputy foreign minister

- Charilaos Florakis · Greek Communist Party general secretary

- Paul Scoon · Grenadian governor-general

- Bernard Coard[137] · Grenadian deputy prime minister and finance minister

- Louis Lansana Beavogui · Guinean prime minister

- Luís Cabral · Bissau-Guinean former president and PAIGC central committee general secretary

- Bishwaishwar Ramsaroop · Guyanese vice president

- Cheddi Jagan · Guyanese National Assembly minority leader and People's Progressive Party general secretary

- René Théodore · Haitian Communist Party general secretary

- Rigoberto Padilla Rush · Honduran Communist Party general secretary

- János Kádár · Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party general secretary

- Pál Losonczi · Hungarian Presidential Council chairman

- Sándor Rajnai · Hungarian ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Haraldur Kröyer · Icelandic ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Indira Gandhi · Indian prime minister

- N.K. Krishnan · Indian Communist Party national council secretary

- Adam Malik · Indonesian vice president

- Mostafa Mir-Salim · Iranian presidential representative and advisor

- Taha Muhie-eldin Marouf · Iraqi vice president

- Patrick Hillery · Irish president

- Michael O'Riordan · Irish Communist Party general secretary

- Meir Vilner · Israeli Communist Party general secretary and Hadash coalition Knesset member

- Amintore Fanfani · Italian Senate of the Republic president

- Emilio Colombo · Italian foreign minister

- Paolo Bufalini · Italian Communist Party member of the Senate of the Republic and Party Provincial Federation of Rome secretary

- Enrico Berlinguer · Italian Communist Party general secretary and member of the Chamber of Deputies

- Giancarlo Pajetta · Italian Communist Party member of the Chamber of Deputies and member of the European Parliament

- Zenkō Suzuki · Japanese prime minister

- Yoshio Sakurauchi · Japanese foreign minister

- Mitsuhiro Kaneko · Japanese Communist Party general secretary

- Ichio Asukata · Japanese Socialist Party chairman

- Mudar Badran · Jordanian prime minister and defence minister

- Heng Samrin[d] · Kampuchean People's Revolutionary Party general secretary and State Council president

- Robert Ouko · Kenyan foreign minister

- Pak Song-chol · North Korean vice president

- Kim Yǒng-ch'ae · North Korean communications minister

- Gil Jae-gyeong · North Korean Workers' Party central committee international department deputy chairman

- Kwon Hee-gyong · North Korean ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Abdulaziz Hussein · Kuwaiti minister of state for cabinet affairs

- Prince Souphanouvong · Laotian president

- Phoumi Vongvichit · Laotian deputy prime minister

- Khamphay Boupha · Laotian deputy foreign minister

- Khamta Duangthongla · Laotian ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Ibrahim Halawi · Lebanese economy, trade & tourism minister

- George Hawi · Lebanese Communist Party general secretary

- Evaristus Rets'elisitsoe Sekhonyana · Lesothoan deputy prime minister and planning, employment & economic affairs minister

- Abdul Salam Jalloud · Libyan former prime minister

- Colette Flesch · Luxembourgish vice president and economic, justice, and foreign affairs minister

- René Urbany · Luxembourgish Communist Party president

- Edouard Rabeony · Malagasy Military Development Committee chairman

- Moussa Traoré · Malian president

- Agatha Barbara · Maltese president

- Anthony Vassallo · Maltese Communist Party general secretary

- Philibert Duféal · Martinican Communist Party general secretary

- Miguel González Avelar · Mexican Senate of the Republic president

- Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal · Mongolian People's Great Khural presidium chairman

- Jambyn Batmönkh · Mongolian Council of Ministers chairman

- D. Gotov · Mongolian ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Prince Sidi Mohammed bin Hassan al-Alawi · Moroccan crown representative

- Ali Yata · Moroccan Party of Progress and Socialism general secretary

- Samora Machel · Mozambican president

- Joaquim Chissano · Mozambican foreign minister

- Mário da Graça Machungo · Mozambican planning minister

- Gijs van Aardenne · Dutch vice prime minister and economic affairs minister

- Daniel Ortega · Nicaraguan Junta of National Reconstruction coordinator

- Moumouni Adamou Djermakoye · Nigerien public health & social affairs minister

- Alex Ifeanyichukwu Ekwueme · Nigerian vice president

- Prince Harald · Norwegian crown representative

- Kåre Willoch · Norwegian prime minister

- Kjell Colding · Norwegian security and foreign affairs state secretary

- Hans Kleven · Norwegian Communist Party chairman

- Muhammad Zia ul-Haq · Pakistani president

- Sahabzada Yaqub Khan · Pakistani foreign minister

- Yasser Arafat · Palestine Liberation Organization chairman

- Na’im al-Ashab · Palestinian Communist Party central committee politburo member and Jordanian Communist Party representative

- Ananías Maidana · Paraguayan Communist Party central committee politburo member

- Imelda Marcos · Filipino first lady, Metro Manila governor, and human settlements minister

- Wojciech Jaruzelski · Polish prime minister and Military Council of National Salvation chairman

- Henryk Jabłoński · Polish State Council chairman

- Józef Czyrek · Polish United Workers' Party central committee secretariat member

- Vasco Futscher Pereira · Portuguese foreign minister

- Álvaro Cunhal · Portuguese Communist Party general secretary

- Nicolae Ceaușescu · Romanian president

- Constantin Dăscălescu · Romanian prime minister

- Ștefan Andrei · Romanian foreign minister

- Libero Barulli and Maurizio Gobbi · Sammarinese captains regent

- Ermenegildo Gasperoni · Sammarinese Communist Party chairman

- Amath Dansokho · Senegalese Party of Independence and Labour deputy general secretary

- Maxime Ferrari · Seychellois foreign minister

- Sorie Ibrahim Koroma · Sierra Leonean vice president

- Moses Mabhida · South African Communist Party general secretary

- Sam Nujoma · South West Africa People's Organisation president

- José Pedro Pérez-Llorca · Spanish foreign minister

- Jaime Ballesteros Pulido · Spanish Communist Party deputy general secretary

- Francisco Romero Marín · Spanish Communist Party central committee presidium member

- Francisco López Real · Spanish Socialist Workers' Party executive committee member

- Abdul Cader Shahul Hameed · Sri Lankan foreign minister

- Prince Bertil · Swedish crown representative

- Olof Palme · Swedish prime minister

- Rolf Hagel · Swedish Communist Party president

- Bo Hammar · Swedish Communist Left Party executive committee member

- Pierre Aubert · Swiss vice president

- Armand Magnin · Swiss National Councillor and Labour Party general secretary

- Hafez al-Assad · Syrian president

- Daniel Naame · Syrian Communist Party central committee politburo member

- Aboud Jumbe · Tanzanian vice president and Zanzibari Revolutionary Council chairman

- Mohammed Chaker · Tunisian justice minister

- Mohamed Harmel · Tunisian Communist Party general secretary

- Bülend Ulusu · Turkish prime minister

- İlter Türkmen · Turkish foreign minister

- Paulo Muwanga · Ugandan vice president

- Francis Pym · British foreign secretary

- Iain Sutherland · British ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Gordon McLennan · British Communist Party general secretary

- Javier Pérez de Cuéllar · United Nations secretary general

- Chikh Békri · UNESCO deputy director-general

- George H. W. Bush · American vice president

- George Shultz · American secretary of state

- Arthur A. Hartman · American ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Gus Hall · American Communist Party general secretary

- Rodney Arismendi · Uruguayan Communist Party general secretary

- Giovanni Battista Marini Bettolo Marconi · Pontifical Academy of Sciences academician council-member and Accademia dei XL president

- José Alberto Zambrano Velasco · Venezuelan foreign minister

- Trường Chinh · Vietnamese State Council chairman

- Nguyễn Cơ Thạch · Vietnamese foreign minister

- Đình Nho Liêm · Vietnamese ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Ali Abdullah Saleh · North Yemeni president

- Ali Nasser Mohammed · South Yemeni president

- Petar Stambolić · Yugoslav Presidency president

- Mitja Ribičič · Yugoslav Presidency member

- Lazar Mojsov · Yugoslav foreign minister

- Milojko Drulović · Yugoslav ambassador to the Soviet Union

- Humphrey Mulemba · Zambian United National Independence Party general secretary

- Canaan Banana · Zimbabwean president

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ According to Brezhnev's physicians these included the medications secobarbital, diazepam, nitrazepam and lorazepam.[6]

- ^ Although Brezhnev's predecessor Nikita Khrushchev did make a formal request to the Central Committee asking to be released from his duties as general secretary due to "advanced age" and the "state of his health",[9] minutes from the meetings held on 13–14 October 1964 indicate his request was not voluntary, with Khrushchev given no choice in the matter to request otherwise.[10]

- ^ The barber Tolya visited Brezhnev twice daily: in the morning for his shave and to have his hair coiffured, and in the afternoon following Brezhnev's midday sleep to have his hair coiffured a second time.[60] According to Medvedev, Tolya's inebriated appearance at Brezhnev's final hair appointment was not an isolated occurrence.[61]

- ^ Kampuchea's de facto government sent their representative to Brezhnev's funeral while its de jure government-in-exile did not attend.

References

edit- ^ Steele (1983), p. 8.

- ^ Kevorkov (1995), p. 205.

- ^ Altman, Lawrence K. (13 November 1982). "4 Serious Ailments Plagued Brezhnev". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45496. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023.

- ^ Schattenberg (2022), p. 201.

- ^ Schattenberg (2022), pp. 312, 314–315, 319, 342–345; Dönninghaus & Savin (2021), pp. 94–96, 99; Raleigh (2016), p. 848; Brezhnev (2016), pp. 900, 929, 953, 1122, 1136; Mitrokhin & Polowy (2009), p. 884; Sukhodrev (2008), p. 352; Korobov (2002), pp. 71–76; Chazov (1992), pp. 126, 129, 131–132.

- ^ Mlechin (2011), p. 554; Korobov (2002), p. 72.

- ^ a b Mlechin (2011), p. 575.

- ^ a b Dönninghaus & Savin (2021), p. 100.

- ^ Artizov (2007), p. 230.

- ^ Artizov (2007), pp. 217, 227–228, 250.

- ^ Schattenberg (2022), pp. 348–349; Gorbachev (1996), p. 114.

- ^ Gorbachev (1995), p. 18.

- ^ Schattenberg (2022), p. 314.

- ^ Burns, John F. (22 February 1982). "Kremlin's Next Occupant: Guessing Game Revives". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45232. p. A2. Archived from the original on 22 February 2023.

- ^ Doder (1988), p. 74.

- ^ a b Burns, John F. (6 March 1982). "After Suslov's Death, A String of Soviet Surprises". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45244. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Finn Ends Moscow Visit". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45249. 11 March 1982. p. A7. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022.

- ^ "Brezhnev Said to Leave Clinic in Moscow". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45274. 5 April 1982. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 532.

- ^ Schattenberg (2022), p. 346; Kolesnichenko (2010), p. 29; Medvedev (2010), pp. 96–97; Doder (1988), p. 64; Solovyov & Klepikova (1986), p. 4.

- ^ a b Medvedev (1983), p. 9.

- ^ Doder, Dusko (2 April 1982). "Brezhnev Reported to Be Seriously Ill". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (1 April 1982). "Brezhnev is Reported in Hospital". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45270. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023.

- ^ Chernyaev (2006), p. 17.

- ^ Burns, John F. (4 April 1982). "Soviet Leaders Clinic Remains Under Close Guard". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45273. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022.

- ^ Arbatov (1992), p. 192.

- ^ Schattenberg (2022), pp. 346, 348.

- ^ "Soviet Union, Lion in Winter: Rumors of Brezhnev's Decline". Time. Vol. 119, no. 15. 12 April 1982. p. 40. ISSN 0040-781X.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (6 April 1982). "Soviet Foreign Ministry Now Says Brezhnev is on a Winter Vacation". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45275. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022.

- ^ Burns, John F. (18 April 1982). "Brezhnev Offers Talk with Reagan in Europe in Fall". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45287. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "Norman Bailey Files (National Security Council) RAC Box 3: Soviet Policy (May 1982–June 1982), Soviet Trends April 1982 — Chronology April 1-30, 1982" (PDF). Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library. 27 May 1982. p. 17.

- ^ Wilson (2016), pp. 531–532.

- ^ Temko, Ned (19 April 1982). "Maneuvering Over Date of A Reagan-Brezhnev Summit". The Christian Science Monitor. Boston. p. 2. Archived from the original on 10 June 2024.

- ^ Smith, Hedrick (6 April 1982). "Reagan Proposes Brezhnev Join Him at the U.N. in June". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45275. Archived from the original on 6 April 2022.

- ^ Wilson (2016), pp. 531–533.

- ^ Wilson (2016), pp. 532–533.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (23 April 1982). "Brezhnev At Rally, Scotching 4 Weeks of Mystery and Rumor". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45292. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022.

- ^ Medvedev (1983), p. 10.

- ^ Burns, John F. (2 May 1982). "A Frail Brezhnev at May Day Parade". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45301. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022.

- ^ "Brezhnev Replies On Nuclear Arms". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45322. 23 May 1982. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (27 May 1982). "KGB Chief Quits for Higher Duties". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45326. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022.

- ^ Chernyaev (2006), p. 28.

- ^ "Polish Leader Visits Brezhnev in Crimea". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45408. 17 August 1982. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022.

- ^ "Soviet Officials Hint Brezhnev May Retire". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45427. 5 September 1982. Archived from the original on 5 September 2022.

- ^ "Support for the P.L.O. Affirmed by Brezhnev". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45437. 15 September 1982. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Soviet Offers a 6-Point Plan for Peace in the Middle East". The New York Times. Vol. 131, no. 45438. 16 September 1982. Archived from the original on 16 September 2022.

- ^ "Mrs. Gandhi Finishes Talks with Brezhnev". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45444. 22 September 1982. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022.

- ^ Bernd Schaefer (translator). "Information about the Visit of Indira Gandhi to the USSR" (30 September 1982) [Memorandum of Conversation]. Cold War International History Project, File: SAPMO-BArch, DY 30, No. 13941, TsK-Abteilung Internationale Beziehungen der Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (German Federal Archives). Wilson Center.

- ^ Doder (1988), p. 97.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (27 September 1982). "Brezhnev Stresses Issue of China Ties". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45449. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021.

- ^ Chernyaev (2010), p. 505; Doder (1988), pp. 96–97; Medvedev (1983), p. 10.

- ^ Burns, John F. (28 October 1982). "Brezhnev Charges U.S. is Threatening Nuclear Conflict". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45480. p. A1. Archived from the original on 28 October 2024.

- ^ Chernyaev (2006), p. 56.

- ^ "Shcharansky Said to Start Hunger Strike in Prison". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45450. Reuters. 28 September 1982. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024.

- ^ Wilson (2016), pp. 761–762.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 766.

- ^ a b Smith, Hedrick (11 November 1982). "U.S. Foresees No Early Policy Shifts". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45494. p. D21.

- ^ Burns, John F. (8 November 1982). "Brezhnev Renews Call for Detente But Warns West". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45491. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Schattenberg (2022), p. 355.

- ^ Musaelyan (2015), p. 145; Medvedev (2010), p. 84.

- ^ a b Medvedev (2010), p. 101.

- ^ Medvedev (2010), p. 102; Karpov (2000), p. 464; Chazov (1992), p. 168.

- ^ Mlechin (2011), p. 612; Medvedev (1983), p. 20.

- ^ Sell (2016), p. 114.

- ^ a b c d e f Blake, Patricia (22 November 1982). "The Soviets: Changing the Guard". Time. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023.

- ^ Krebs, Albin (15 May 1990). "Andrei P. Kirilenko Dead at 84; A Brezhnev Ally in the Politburo". The New York Times. Vol. 139, no. 48236. p. B6. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022.

- ^ a b Weisman, Steven R. (12 November 1982). "Brezhnev Dead at 75; No Successor Named; Reagan Pledges an Effort to Improve Ties". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45495. p. A12. Archived from the original on 12 November 2023.

- ^ "Igor Kirillov, Soviet Union's Leading Anchorman Who Delivered the Official Line, from Gagarin's Spaceflight to the Fall of the Berlin Wall, is Dead of Covid-19 at 89". The Times. 9 November 2021. Archived from the original on 26 October 2024.

- ^ Seale (1990), p. 398.

- ^ Kim (2011), pp. 59–60.

- ^ "World Praises, Condemns Brezhnev". UPI. 12 November 1982.

- ^ Nutting (1983), p. 57.

- ^ "A Wake-Up Call for Reagan, A Gold Rush in Hong Kong" (PDF). Manchester Herald. Manchester, CT. UPI. 11 November 1982. p. 4.

- ^ "World Leaders Comment on Brezhnev's Death". UPI. 11 November 1982.

- ^ Daily Report: Soviet Union. The Service. 1982. p. 18.

- ^ Reid (1982), p. 33.

- ^ a b Wilson (2016), p. 783.

- ^ "Reagan Visits the Soviet Embassy". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45497. 14 November 1982. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 784.

- ^ Dobrynin (1995), pp. 511–512.

- ^ Ebon (1983), pp. 269–270.

- ^ Ebon (1983), p. 272.

- ^ Burns, John F. (13 November 1982). "Andropov is Chosen to Head Soviet Party; Vows He Will Continue Brezhnev Policies". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45496. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023.

- ^ Seale (1990), p. 398; Medvedev (1983), p. 20.

- ^ "At Brezhnev's Bier, Grandeur, Gloom and the Lurking Presence of the KGB". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45496. 13 November 1982. p. A4. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (14 November 1982). "Huge Gathering of World Leaders is Expected for Brezhnev's Funeral". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45497. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023.

- ^ Ford (2016), p. 77.

- ^ Blake, Patricia (29 November 1982). "Soviet Union: The Andropov Era Begins". Time. Archived from the original on 29 November 2023.

- ^ Rudnev (1974), pp. 126–127.

- ^ Bacon (2002), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Chernyaev (2006), p. 68.

- ^ Medvedev (1983), p. 23.

- ^ Bacon (2002), p. 6.

- ^ "Text of Andropov's Speech at Brezhnev's Funeral". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45499. Translated by the Soviet press agency TASS. AP. 16 November 1982. p. A10. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023.

- ^ a b Burns, John F. (16 November 1982). "Brezhnev Buried Amid Moscow Pomp". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45499. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023.

- ^ a b Речъ A.П. Алeкcaндрoвa, B.В. Пyшкapeвa и A.Ф. Гopдиeнкo [Speeches by A.P. Alexandrov, V.V. Pushkarev and A.F. Gordienko]. Известия [Izvestia] (in Russian). Vol. 320, no. 20301. 16 November 1982.

- ^ a b Doder, Dusko (16 November 1982). "Brezhnev Buried Next to Stalin in Moscow Rites". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023.

- ^ Ford (2016), p. 78.

- ^ "Bush, Shultz, Soviet Chief Huddle as Brezhnev Buried in Stolid Style; Security Blankets Red Square Rites". Miami Herald. 16 November 1982. Archived from the original on 16 November 2024.

- ^ Rudnev (1974), p. 127.

- ^ Doder (1988), p. 108.

- ^ Medvedev (1983), pp. 23–24.

- ^ "Didn't Drop Body of Brezhnev, Soviet Gravedigger Says". Los Angeles Times. United Press International. 7 June 1990. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022.

- ^ Sumiala, Lounasmeri & Lukyanova (2022), p. 269.

- ^ a b Chernyaev (2006), p. 66.

- ^ Brown (2022), pp. 122, 382.

- ^ Gotlieb (2007), p. 106.

- ^ Young (2017), p. 110.

- ^ Igor Kirillov (15 November 1982). Время – похороны брежнева – иностранные сановники торжественное возложение и прием в георгиевском зале кремля [Vremya – Brezhnev's Funeral – Foreign Dignitaries at the Lying-in-State Ceremony and Reception in the Georgievsky Hall of the Kremlin] (Elektronika VM-12) (Videotape). Время. Event occurs at 29:05.

- ^ Wilson (1986), p. 113.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (19 December 1982). "USSR Turns 60, But Some 'Friends' Will Skip the Party". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45532. Archived from the original on 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Transcript of President Reagan's News Conference on Foreign and Domestic Matters". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45495. 12 November 1982. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Daily Diary of President Ronald Reagan: Monday, November 15, 1982" (PDF). Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library.

- ^ "Bush to Interrupt Tour Of Africa for Funeral". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45496. 13 November 1982. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021.

- ^ Merry (2010), p. 121.

- ^ Gwertzman, Bernard (13 November 1982). "U.S. Delegation To Seek Talks in Moscow". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45496. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (15 November 1982). "Bush and Shultz Voice Hope of Gain in Ties with Soviet". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45498. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021.

- ^ Chernyaev (2006), pp. 66, 68–69.

- ^ "Actor Asks to Attend Brezhnev's Funeral". UPI. 12 November 1982. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024.

- ^ Weintraub & Cohen (2011), pp. 238–241.

- ^ Weintraub & Cohen (2011), p. 240.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 795.

- ^ Merry (2010), p. 122.

- ^ "Bush Holds Frank Talks With Soviet". Miami Herald. 16 November 1982. Archived from the original on 16 November 2024.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 785.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 786.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 788.

- ^ Wilson (2016), pp. 788, 795.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 791.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 793.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (16 November 1982). "Bush Meets with Andropov in Brief, 'Substantive' Talks". The New York Times. Vol. 132, no. 45499. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021.

- ^ Wilson (2016), pp. 794–795.

- ^ Wilson (2016), p. 794.

- ^ Reagan, Ronald. "White House Diaries Entry: Tuesday, November 16, 1982". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library.

- ^ Похороны Леонида Ильича Брежнева: Траурный митинг на Красной площади - Здесь же - многочисленные зарубежные гости, прибывшие на похороны Л.И. Брежнева [The Funeral of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev: Mass Service in Red Square – Foreign Guests In Attendance]. Правда [Pravda] (in Russian). Vol. 320, no. 23481. 16 November 1982.

- ^ Appearances of Soviet Leaders, January-December 1982 (PDF). Vol. CR 83-10605. Washington, D.C.: United States Central Intelligence Agency Directorate of Intelligence. March 1983. pp.197-198 (print), pp.482-483 (pdf). OCLC 32705401.

- ^ Chronology of Soviet Statements and Actions in Grenada: 7 September 1979 to 27 October 1983 (PDF) (Report). CIA. 30 October 1983.

Works cited

edit- Arbatov, Georgi A. (1992). The System: An Insider's Life in Soviet Politics (1st ed.). New York: Times Books. ISBN 0-81-29-1970-X. OCLC 1044127993.

- Artizov, Andrey N. [in Russian], ed. (2007). Никита Хрущев 1964: стенограммы пленума ЦК КПСС и другие документы [Nikita Khrushchev 1964: Transcripts of the Plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU] (in Russian). Moscow: Meždunarodnyj fond "Demokratija", Materik. ISBN 978-5-85646-173-1. OCLC 872163601.

- Bacon, Edwin (2002). "Reconsidering Brezhnev". In Bacon, Edwin; Sandle, Mark (eds.). Brezhnev Reconsidered. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780230501089. ISBN 978-0333794630. OCLC 1156652094.

- Brezhnev, Leonid (2016) [original date 1978-1982]. Artizov, Andrey N.; Dönninghaus, Victor; Ketzer, N.; Stepanov, A.S.; Korotkov, A.V. (eds.). Рабочие и дневниковые записи Леонида Брежнева в 3-х томах 1964-1982 [Work and Diary Entries of Leonid Brezhnev in Three Volumes 1964-1982] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Historical Literature. ISBN 978-5-99089-431-0. OCLC 1075979846.

- Brown, Archie (2022). The Human Factor: Gorbachev, Reagan, Thatcher, and the End of the Cold War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285653-1. OCLC 1295403442.

- Chazov, Evgeny I. [in Russian] (1992). Здоровье и власть: воспоминания кремлевского врача [Health and Power: Memories of a Kremlin Doctor] (in Russian). Moscow: Центрполиграф (Tsyentrpoligraf). ISBN 978-5-227-05794-5. OCLC 952184379.

- Chernyaev, Anatoly (2006). The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev – 1982. Translated by Anna Melyakova. National Security Archive. OCLC 144513966.

- Chernyaev, Anatoly (2010). Совместный исход: дневник двух эпох 1972-1991 [Common Outcome: Diary of Two Eras 1972-1991] (in Russian). Moscow: РОССПЭН (ROSSPEN). ISBN 9785824310252. OCLC 294760583.

- Dobrynin, Anatoly (1995). In Confidence: Moscow's Ambassador to America's Six Cold War Presidents. Univ Of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99644-8. OCLC 941875130.

- Doder, Dusko (1988). Shadows and Whispers: Power Politics Inside the Kremlin from Brezhnev to Gorbachev. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-010526-1. OCLC 15791133.

- Dönninghaus, Victor [in German]; Savin, Andrey I. (2021). Секрет, завернутый в тайну: здоровье Леонида Брежнева как элемент государственного механизма [A Riddle Wrapped in a Mystery: Health of Leonid Brezhnev as an Element of State Apparatus]. Гуманитарные науки в Сибири [Humanitarian Sciences in Siberia] (in Russian). 28 (3). Novosibirsk: Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences: 92–100. doi:10.15372/HSS20210313. S2CID 244333989.

- Ebon, Martin (1983). The Andropov File: The Life and Ideas of Yuri V. Andropov, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-018861-7. OCLC 9417207.

- Ford, Joseph A. (2016). "The Deaths of the General Secretaries of the CPSU". Funerary Practices and Political Succession: Three Regime Types (PhD thesis). The University of Chicago. ProQuest 1813705289.

- Gorbachev, Mikhail S. (1995). Жизнь и pеформы [Life and Reforms] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Новости. ISBN 978-5-7020-0953-7. OCLC 36023550.

- Gorbachev, Mikhail S. (1996). Memoirs. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385480192. OCLC 35270037.

- Gotlieb, Allan (2007). The Washington Diaries, 1981-1989. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-3563-0. OCLC 148996656.

- Karpov, Vladimir (2000). Вечерние беседы с Викторией Брежневой [Evening Conversations with Victoria Brezhneva]. Расстрелянные маршалы [Executed Marshals] (in Russian). Moscow: Вече (Veche). ISBN 978-5-7838-0526-4. OCLC 44649019.

- Kevorkov, Vjac̆eslav [in Russian] (1995). Der geheime Kanal: Moskau, der KGB und die Bonner Ostpolitik (The Secret Channel: Moscow, the KGB and Bonn's Ostpolitik) (in German). Rowohlt. ISBN 978-3-87134-224-0. OCLC 35789523.

- Kim, Yong-ho (2011). North Korean Foreign Policy: Security Dilemma and Succession. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-4862-4. OCLC 1291957293.

- Kolesnichenko, Aleksandr (2010). Как попасть в историю и анекдот. леонид ильич был одним из самых рисковых совецих вождей [The Risks Taken By Brezhnev: An Historical Anecdote]. Аргументы и факты [Arguments and Facts] (in Russian). 26 (21). Archived from the original on 19 November 2021 – via the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation.

- Korobov, Pavel (2002). К 75 годам Леонид Ильич совсем расслабился: интервью с Михаилом Косаревым, лечащим врачом Л. Брежнева [Interview with Mikhail Kosarev, the Attending Physician of L. Brezhnev]. Коммерсантъ-Власть [Kommersant-Vlast] (in Russian). 44. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021.

- Medvedev, Vladimir T. [in Russian] (2010). Человек за спиной [The Man Behind His Back] (in Russian) (2 ed.). Moscow: УП Принт (UP Print). ISBN 978-5-91487-010-9. OCLC 714329786.

- Medvedev, Zhores A. (1983). Andropov. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-01791-5. OCLC 1222889441.

- Merry, E. Wayne (2010). "Moscow, USSR—Consular/Political (Internal) Officer 1980-1983: Brezhnev's Death" (PDF). Foreign Affairs Oral History Project (Interview). Interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy. Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training.

- Mitrokhin, Nikolay; Polowy, Teresa (2009). "'Strange People' in the Politburo: Institutional Problems and the Human Factor in the Economic Collapse of the Soviet Empire". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 10 (4): 869–896. doi:10.1353/kri.0.0120. S2CID 159880095.

- Mlechin, Leonid M. (2011). Брежнев [Brezhnev] (in Russian). Moscow: Молодая гвардия (Molodaya Gvardiya). ISBN 978-5-235-03432-7. OCLC 799895105.

- Musaelyan, Vladimir (2015). Брежнев, которого не знали [Brezhnev, Whom They Didn't Know]. Коллекция Караван историй [Caravan of Stories Collection] (in Russian). Vol. 7. Moscow: 7days.

- Nutting, Wallace H. (1983). "Politico-Military Summary: Argentina". United States Southern Command 1982 Historical Report (PDF) (Report). 16-025-MDR. US Department of Defence – via the USSOUTHCOM/FOIA Office.

- Raleigh, Donald J. (2016). "Soviet Man of Peace: Leonid Il'ich Brezhnev and His Diaries". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 17 (4). doi:10.1353/kri.2016.0051. S2CID 157183233.

- Reid, Ptolemy (1982). "National Assembly Minutes: Sympathy on Death of Cde. Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev". Proceedings and Debates of the Second Session of the National Assembly of the Fourth Parliament Under the Constitution of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana (PDF) (Report). Vol. 9 – via the Guyanese National Assembly.

- Rudnev, Vladimir A. (1974). Советские обычаи и обряды [Soviet Customs and Rituals] (in Russian). Leningrad: Лениздат. OCLC 29554671.

- Schattenberg, Susanne [in German] (2022). Brezhnev: The Making of A Statesman. Translated by John Heath. I.B. Tauris, Bloomsbury PLC. doi:10.7788/9783412509934. ISBN 978-1-83860-638-1. OCLC 1227916961. S2CID 186937428.

- Seale, Patrick (1990). Asad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East. University of California Press. ISBN 978-1850430612. OCLC 717131521.

- Sell, Louis (2016). "Interregnum: Andropov in Power". From Washington To Moscow. Duke University Press. doi:10.1515/9780822374008-009. ISBN 978-0-8223-7400-8. S2CID 156286422.

- Solovyov, Vladimir; Klepikova, Elena (1986). Behind the High Kremlin Walls. Dodd, Mead & Co. ISBN 978-0-396-08710-6. OCLC 869170782.

- Steele, Jonathan (1983). Soviet Power: The Kremlin's Foreign Policy - Brezhnev to Andropov. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-49209-0. OCLC 489788029.

- Sukhodrev, Viktor M. (2008). Язык мой-друг мой: от Хрущева до Горбачева [My Language is My Friend: From Khrushchev to Gorbachev] (in Russian). Moscow: Тончу. ISBN 978-5-91215-010-4. OCLC 244952560.

- Sumiala, Johanna; Lounasmeri, Lotta; Lukyanova, Galina (2022). "Almost Immortal? The Ritual Transition of Power and the Dynamics of History in Three Cold War Media Events". Media History. 28 (2): 261–277. doi:10.1080/13688804.2021.1958671. S2CID 237681346.

- Weintraub, Jerry; Cohen, Rich (2011). When I Stop Talking, You'll Know I'm Dead. Twelve. ISBN 978-0-446-54816-8. OCLC 1073614353.

- Wilson, Boyd H. (1986). "Vinoba Bhave's Talks on the Gita". In Minor, Robert Neil (ed.). Modern Indian Interpreters of the Bhagavadgita. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-297-1. OCLC 751652796.

- Wilson, James G., ed. (2016). Soviet Union, January 1981–January 1983 (PDF). Foreign Relations of the United States 1981–1988 (Report). Vol. III. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Young, Huguette (2017). Justin Trudeau: The Natural Heir. Toronto: CNIB. ISBN 978-1-5252-6284-5. OCLC 1012508783.

External links

edit- Video of Brezhnev's state funeral

- Сообщение о смерти Л.И. Брежнева (11 November 1982) Original announcement of Brezhnev's death on Soviet television (in Russian)

- Время (15 November 1982) Abbreviated Soviet news report on Brezhnev's funeral, burial, and funeral reception (in Russian)

- CBS Evening News (11 November 1982) American news report on Brezhnev's death announcement

- CBS Evening News (14 November 1982) American news report on Vice President Bush's appearance at Brezhnev's lying in state (event occurs at 0:52 sec.)

- NBC Nightly News (2 April 1982) American news report on Brezhnev's hospitalization following his visit to Tashkent (event occurs at 14 mins 09 sec.)

- Brezhnev's tomb in Moscow at Wikimapia