Damnatio ad bestias (Latin for "condemnation to beasts") was a form of Roman capital punishment where the condemned person was killed by wild animals, usually lions or other big cats. This form of execution, which first appeared during the Roman Republic around the 2nd century BC, had been part of a wider class of blood sports called Bestiarii.

The act of damnatio ad bestias was considered a common form of entertainment for the lower class citizens of Rome (plebeians). Killing by wild animals, such as Barbary lions,[1] formed part of the inaugural games of the Flavian Amphitheatre in AD 80. Between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, this penalty was also applied to the worst of criminals, runaway slaves, and Christians.

History

editThe exact purpose of the early damnatio ad bestias is not known and might have been a religious sacrifice rather than a legal punishment,[2] especially in the regions where lions existed naturally and were revered by the population, such as Africa, India and other parts of Asia. For example, Egyptian mythology had a chimeric Underworld demon, Ammit, who devoured the souls of exceptionally sinful humans, as well as other lion-like deities, such as Sekhmet, who, according to legend, almost devoured all of humanity soon after her birth. There are also accounts of feeding lions and crocodiles with humans, both dead and alive, in Ancient Egypt and Libya.[citation needed]

Similar condemnations are described by historians of Alexander the Great's campaigns in Central Asia. A Macedonian named Lysimachus, who spoke before Alexander for a person condemned to death, was himself thrown to a lion, but overcame the beast with his bare hands and became one of Alexander's favorites.[3] It is important to note that this has no real proof, and if real was likely a weakened/juvenile lion. In northern Africa, during the Mercenary War, Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca threw prisoners to the beasts,[4] whereas Hannibal forced Romans captured in the Punic Wars to fight each other, and the survivors had to stand against elephants.[5]

Lions were rare in Ancient Rome and human sacrifice was banned there by Numa Pompilius in the 7th century BC, according to legend. Damnatio ad bestias appeared there not as a spiritual practice but rather a spectacle. In addition to lions, other animals were used for this purpose, including dogs, wolves, bears, leopards, tigers, hyenas, and crocodiles. It was combined with gladiatorial combat and was first featured at the Roman Forum and then transferred to the amphitheaters.[citation needed]

Terminology

editWhereas the term damnatio ad bestias is usually used in a broad sense, historians distinguish two subtypes: obicĕre bestiis[citation needed] (to throw to beasts) where the humans are defenseless, and damnatio ad bestias, where the punished are both expected and prepared to fight.[6] In addition, there were professional beast fighters trained in special schools, such as the Roman Morning School, which received its name by the timing of the games.[7] These schools taught not only fighting but also the behavior and taming of animals.[8] The fighters were released into the arena dressed in a tunic and armed only with a spear (occasionally with a sword). They were sometimes assisted by venators (hunters),[9] who used bows, spears and whips. Such group fights were not human executions but rather staged animal fighting and hunting. Various animals were used, such as elephants, rhinoceroses, wild boars, buffaloes, hippopotamuses, aurochs, bears, lions, tigers, leopards, hyenas, and wolves. The first such staged hunting (Latin: venatio) featured lions and panthers, and was arranged by Marcus Fulvius Nobilior in 186 BC at the Circus Maximus on the occasion of the Greek conquest of Aetolia.[10][11] The Colosseum and other circuses still contain underground hallways that were used to lead the animals to the arena.

History and description

editThe custom of submitting criminals to lions was brought to ancient Rome by two commanders, Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, who defeated the Macedonians in 167 BC, and his son Scipio Aemilianus, who conquered the African city of Carthage in 146 BC.[13] It was originally a military punishment, possibly borrowed from the Carthaginians. Rome reserved its earliest use for non-Roman military allies found guilty of defection or desertion.[2] The sentenced were tied to columns or thrown to the animals, practically defenseless (i.e. obicĕre bestiis).

Some documented examples of damnatio ad bestias in Ancient Rome include the following: Strabo witnessed[14] the execution of the rebel slaves' leader Selurus.[15][11] The bandit Laureolus was crucified and then devoured by an eagle and a bear, as described by the poet Martial in his Book of Spectacles.[16][17] Such executions were also documented by Seneca the Younger (On anger, III 3), Apuleius (The Golden Ass, IV, 13), Titus Lucretius Carus (On the Nature of things) and Petronius Arbiter (Satyricon, XLV). Cicero was indignant that a man was thrown to the beasts to amuse the crowd just because he was considered ugly.[18][19] Suetonius wrote that when the price of meat was too high, Caligula ordered prisoners, with no discrimination as to their crimes, to be fed to circus animals.[20] Pompey used damnatio ad bestias for showcasing battles and, during his second consulate (55 BC), staged a fight between heavily armed gladiators and 18 elephants.[5][21][22]

The most popular animals were tigers, which were imported to Rome in significant numbers specifically for damnatio ad bestias.[11] Brown bears, brought from Gaul, Germany and even North Africa, were less popular.[23][24] Local municipalities were ordered to provide food for animals in transit and not delay their stay for more than a week.[11][25] Some historians believe that the mass export of animals to Rome had a serious impact on wildlife numbers in North Africa.[26]

Execution of Christians

editThe use of damnatio ad bestias against Christians began in the 1st century AD. Tacitus states that during the first persecution of Christians under the reign of Nero (after the Fire of Rome in AD 64), people were wrapped in animal skins (called tunica molesta) and thrown to dogs.[27] This practice was followed by other emperors who moved it into the arena and used larger animals. Application of damnatio ad bestias to Christians was intended to equate them with the worst criminals, who were usually punished this way.

There is a widespread view among contemporary specialists[28] that the prominence of Christians among those condemned to death in the Roman arena was greatly exaggerated in earlier times. There is no evidence for Christians being executed at the Colosseum in Rome.[29]

According to Roman laws, Christians were:[30][better source needed]

- Guilty of high treason (majestatis rei)

- For their worship Christians gathered in secret and at night, making unlawful assembly, and participation in such collegium illicitum or coetus nocturni was equated with a riot.

- For their refusal to honor images of the emperor by libations and incense

- Dissenters from the state gods (άθεοι, sacrilegi)

- Followers of magic prohibited by law (magi, malefici)

- Confessors of a religion unauthorized by the law (religio nova, peregrina et illicita), according to the Twelve Tables).

The spread of the practice of throwing Christians to beasts was reflected by the Christian writer Tertullian (2nd century AD). He states that the general public blamed Christians for any general misfortune and after natural disasters would cry "Away with them to the lions!" This is the only reference from contemporaries mentioning Christians being thrown specifically to lions. Tertullian also wrote that Christians started avoiding theatres and circuses, which were associated with the place of their torture.[31]

"The Passion of St. Perpetua, St. Felicitas, and their Companions", a text which purports to be an eyewitness account, as written by Vibia Perpetua, of a group of Christians condemned to damnatio ad bestias at Carthage in AD 203, states that the men were required to dress in the robes of a priest of the Roman god Saturn, the women as priestesses of Ceres. They were brought back out in separate groups and first the men, then the women, exposed to a variety of wild beasts.

At the resistance of Perpetua, however, the tribune relented and the prisoners were allowed to enter wearing their own clothing.[32] The two young women, Perpetua and a slave girl Felicitas, were reserved as a finale to the executions to face a wild cow. Since it was thought that public nudity would not cast doubt on their fidelity, further degradation was added by not only fully exposing them to the beast but using one of their own sex rather than the usual male animal. The implication was that the women were shown as not being women enough to commit adultery.[33] After having all their clothing removed Perpetua and Felicitas were driven into the arena covered only in see-through netting. As this proved too much for the crowd, they were brought back to be clothed in plain loose garments before being sent in again to face the beast.[34]

This is also not the only instance of such treatment being used on Christian women, many also customarily subjected to other punishments and harsh tortures beforehand.[35] More generally though, in contrast to their clothed male counterparts, women were tied fully naked to stakes or pillars with their hands behind their backs.[36] Full body exposure of a female to a bull after being entirely stripped of all her clothing was one aspect of her shaming, the implications being that she was not regarded in the same way as attired male competitors and allowed to fight any "beast" but rendered helpless, and that being denuded in public would imply a charge of adultery on the part of the woman.[33]

Those who survived the first animal attacks were either brought back out for further exposure to the beasts or executed in public by a gladiator.[37]

The persecution of Christians ceased by the 4th century AD. The Edict of Milan (AD 313) gave them freedom of religion.

Penalty for other crimes

editRoman laws, which are known to us through the Byzantine collections, such as the Code of Theodosius and Code of Justinian, defined which criminals could be thrown to beasts (or condemned by other means). They included:

- Deserters from the army[38]

- Those who employed sorcerers to harm others, during the reign of Caracalla.[39] This law was re-established in AD 357 by Constantius II[40]

- Poisoners; by the law of Cornelius, patricians were beheaded, plebeians thrown to lions, and slaves were crucified[38][41]

- Counterfeiters, who could also be burned alive[38][42]

- Political criminals. For example, after the overthrow and assassination of Commodus, the new emperor threw to lions both the servants of Commodus and Narcissus who strangled him. Even though Narcissus brought the new emperor to power, he committed a crime of murdering the previous one.[43] The same punishment was applied to Mnesteus who organized the assassination of Emperor Aurelian.[44]

- Patricides, who were normally drowned in a leather bag filled with snakes (poena cullei), but could be thrown to beasts if a suitable body of water was not available.[38]

- Instigators of uprisings, who were either crucified, thrown to beasts or exiled, depending on their social status.[45]

- Those who kidnapped children for ransom, according to the law of AD 315 by the Emperor Constantine the Great,[40] were either thrown to beasts or beheaded.

The sentenced was deprived of civil rights; he could not write a will, and his property was confiscated.[46][47] Exception from damnatio ad bestias was given to military servants and their children.[38] Also, the law of Petronius (Lex Petronia) of AD 61 forbade employers to send their slaves to be eaten by animals without a judicial verdict. Local governors were required to consult a Roman deputy before staging a fight of skilled gladiators against animals.[48]

The practice of damnatio ad bestias was abolished in Rome in AD 681.[6] It was used once after that in the Byzantine Empire: in 1022, when several disgraced generals were arrested for plotting a conspiracy against Emperor Basil II, they were imprisoned and their property seized, but the royal eunuch who assisted them was thrown to lions.[49]

Notable victims, according to various Christian traditions

edit- Ignatius of Antioch (AD 107, Rome)[50]

- Glyceria (AD 141, Trayanopolis, Thrace)[51]

- Blandina (AD 177, Lyon)

- Perpetua and Felicity, Saturus and others (AD 203, presumably Carthage)

- Germanicus, second half of the 2nd century, Smyrna, (mentioned in the Martyrdom of Polycarp of Smyrna)

- Euphemia, (AD 303, probably at Chalcedon)

- Marciana of Mauretania, (AD 303, Caesarea, Mauretania Caesariensis)

- Agapius (AD 306, Caesarea)

Survived, according to various legends

edit- An early description of escape from the death by devouring is in the story of Daniel in the Book of Daniel (c. 2nd century BC).

- The Greek writer Apion (1st century AD) tells the story of a slave Androcles (during Caligula's rule) who was caught after fleeing his master and thrown to a lion. The lion spared him, which Androcles explained by saying that he pulled a thorn from the paw of the very same lion when hiding in Africa, and the lion remembered him.[52]

- Mammes of Caesarea, according to Christian legend

- Paul (according to apocrypha and the medieval legends, based on his note "when I have fought with beasts at Ephesus", 1 Corinthians, 15:32)

- Thecla, according to the apocryphal story Acts of Paul and Thecla

- An anecdotal escape is reported in the biography of Emperor Gallienus (in the Augustan History).[53] A man was caught after selling the emperor's wife glass instead of gems. Gallienus sentenced him to face lions, but ordered that a capon rather than a lion be let into the arena. The emperor's herald then proclaimed "he has forged, and was treated the same". The merchant was then released.

Description in popular culture

editLiterature

edit- Tommaso Campanella in his utopia The City of the Sun suggests using damnatio ad bestias as a form of punishment.[54]

- George Bernard Shaw. Androcles and the Lion

- Henryk Sienkiewicz. Quo Vadis

- Lindsey Davis. Two for the Lions

Film

edit- Fights against wild animals in the arena of the Roman Colosseum were displayed in Gladiator (2000) and other films.

Music

edit- The Canadian death metal band Ex Deo has a song titled "Pollice Verso (Damnatio ad Bestia)" on the album Caligvla.

- The British black metal band Cradle of Filth has a song titled "You will know the Lion by his Claw" and uses this line in its lyrics.

- The Hungarian black metal band Harloch[55] has an album Damnatio ad bestias.[56][57]

-

Martyr in the Circus Arena by Fyodor Bronnikov, 1869

-

Martyrdom of Saint Marcienne, 15th-century miniature

-

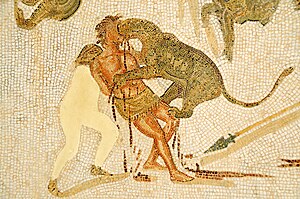

Bear devouring a criminal. Roman mosaic

-

Ignatius of Antioch torn by lions

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "African lion, Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (PDF). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-2831700458.

- ^ a b Alison Futrell (November 2000). Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power. University of Texas Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-292-72523-2. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Гаспаров М.Л. Занимательная Греция. Infoliolib.info. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ Polybius. General History of I 82, 2

- ^ a b Pliny the Elder. Natural history. VIII, Sec. VII.

- ^ a b Тираспольский Г. И. Беседы с палачом. Казни, пытки и суровые наказания в Древнем Риме (Conversations with an executioner. Executions, torture and harsh punishment in ancient Rome). Moscow, 2003. (in Russian)

- ^ Библиотека Archived 2004-09-02 at the Wayback Machine. Invictory.org. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ Гладиаторы Archived 2008-09-16 at the Wayback Machine. 4ygeca.com. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ "Venatio I". cuny.edu. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Livy. History of Rome from the founding of the city XXXIX 22, 2

- ^ a b c d Мария Ефимовна Сергеенко. Krotov.info. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ Micke-Broniarek, Ewa (2006). Gallery of Polish painting. Muzeum Narodowe w Warzawie. p. 151. ISBN 8371003277.

Represented by Siemiradzki is the ancient Roman staging of the myth at the Emperor Nero's wish. He ordered that a young fair Christian woman be put to death in the same way as part of the games at the amphitheatre.

- ^ Livy. Epitoma. "History of Rome from the founding of the city"

- ^ Strabo, VI, II, 6

- ^ Strabo. "Geography: Book VI, Chapter 2". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ Martialis. Liber spectaculorum. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Martialis.net, М. Валерий Марциал Archived 2011-07-23 at the Wayback Machine. Martialis.net. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ Cicero. Letters. Vol. 3. p. 461. Letter (Ad) Fam., VII, 1. (DCCCXCV, 3)

- ^ Cicero. Letters. Vol. 1. p. 258. Letter (Ad) Fam., VII, 1. (CXXVII, 3)

- ^ Suetonius. Lives of the Twelve Caesars. p. 118 (IV Gaius Caligula, 27, 1)

- ^ Dio Cassius. Roman history XXXIX in 1938, 2.

- ^ Plutarch. Pompey, 52

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural History VIII, 64

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural history. VIII, 53

- ^ Cod. Theod. XV; tit. XI. 1–2

- ^ Немировский. История древнего мира. (The history of the ancient world) Ch. 1. p. 86 // Тираспольский Г. И. Беседы с палачом (Conversations with an executioner)

- ^ Tacitus. Annals, XV, 44

- ^ "Secrets of the Colosseum". smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Hopkins, Keith (2011). The Colosseum. Profile Books. p. 103. ISBN 978-1846684708.

- ^ Гонения на христиан в Римской империи Archived 2008-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Ateismy.net. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ "О прескрипции против еретиков". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- ^ Shaw, Brent D. The Passion of Perpetua. p. 5.

- ^ a b Shaw, Brent D. The Passion of Perpetua. p. 7.

- ^ Shaw, Brent D. The Passion of Perpetua. p. 9.

- ^ Shaw, Brent D. The Passion of Perpetua. p. 18.

- ^ Shaw, Brent D. The Passion of Perpetua. p. 8.

- ^ Bomgardner, D.L. (10 October 2002). The Story of the Roman Amphitheatre. Routledge. pp. 141–143. ISBN 978-0415301855.

- ^ a b c d e "The Civil Law". sps11.

- ^ Волхвы (Volkhvy) (in Russian)

- ^ a b "The Civil Law". sps15.

- ^ (истории) Archived 2009-09-09 at the Wayback Machine. www.diet.ru. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ "ГЛАВА 1. ИСТОРИЯ И ПРЕДПОСЫЛКИ ВОЗНИКНОВЕНИЯ ФАЛЬШИВОМОНЕТНИЧЕСТВА // Право России". Allpravo.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ VI: Светлейший муж Вулкаций Галликан. АВИДИЙ КАССИЙ, Властелины Рима. Биографии римских императоров от Адриана до Диоклетиана. Krotov.info. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ XXVI: Флавий Вописк Сиракузянин. БОЖЕСТВЕННЫЙ АВРЕЛИАН, Властелины Рима. Биографии римских императоров от Адриана до Диоклетиана. Krotov.info. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ Grafsky, V. G. "General History of Law and State" (in Russian).

- ^ "The Civil Law". sps6.

- ^ Digests of Justinian. Vol. 7–2. Moscow. 2005. p. 191, fragment 29.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Digests of Justinian. Vol. 7–2. Moscow. 2005. p. 191, fragment 31.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "История Византии. Том 2 (Сборник)". Historic.ru. 2 June 2005. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Frank Northen Magill; Christina J. Moose; Alison Aves (1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The ancient world. Taylor & Francis. p. 587. ISBN 978-0893563134. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ St. Glyceria, Virginmartyr, at Heraclea|Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese. Antiochian.org. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ Aulus Gellius (2nd century), Attic Nights, Vol. 14

- ^ Властелины Рима. Krotov.info. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ ГОРОД СОЛНЦА Томмазо Кампанелла. Krotov.info. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ "Harloch – Encyclopaedia Metallum: The Metal Archives". metal-archives.com. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Harloch – Damnatio ad Bestias – Encyclopaedia Metallum: The Metal Archives". metal-archives.com. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Damnatio ad Bestias". harloch.hu. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

Bibliography

edit- Scott, S. P. (1932). The Civil Law, including The Twelve Tables, The Institutes of Gaius, The Rules of Ulpian, The Opinions of Paulus, The Enactments of Justinian, and The Constitutions of Leo.. Central Trust Company.

Further reading

edit- Donald G. Kyle (1998). Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome. Routledge. ISBN 0415096782.

- Katherine E. Welch (2007). The Roman Amphitheatre – From its Origins to the Colosseum. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521809443.

- Boris A. Paschke (2006). "The Roman ad bestias Execution as a Possible Historical Background for 1 Peter 5.8". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. 28 (4): 489–500. doi:10.1177/0142064x06065696. S2CID 170597982.