Criccieth, also spelled Cricieth ([ˈkrɪkjɛθ] ⓘ), is a town and community in Gwynedd, Wales, on the boundary between the Llŷn Peninsula and Eifionydd. The town is 5 miles (8 km) west of Porthmadog, 9 miles (14 km) east of Pwllheli and 17 miles (27 km) south of Caernarfon. It had a population of 1,826 in 2001,[1] reducing to 1,753 at the 2011 census.[2]

Criccieth

| |

|---|---|

The ruins of Criccieth Castle dominate the town | |

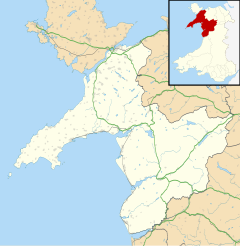

Location within Gwynedd | |

| Population | 1,753 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SH505385 |

| Community |

|

| Principal area | |

| Preserved county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CRICCIETH |

| Postcode district | LL52 |

| Dialling code | 01766 |

| Police | North Wales |

| Fire | North Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament | |

The town is a seaside resort, popular with families.[3] Attractions include the ruins of Criccieth Castle, which have extensive views over the town and surrounding countryside.[4] Nearby on Castle Street is Cadwalader's Ice Cream Parlour, opened in 1927,[5] and the High Street has several bistro-style restaurants.[3] In the centre is Y Maes, part of the original medieval town common.[6]

The town is noted for its fairs, held on 23 May and 29 June every year, when large numbers of people visit the fairground and the market which spreads through many of the streets of the town.[7]

Criccieth hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1975,[8] and in 2003 was granted Fairtrade Town status.[9] It won the Wales in Bloom competition each year from 1999 to 2004.[10]

The town styles itself the "Pearl of Wales on the Shores of Snowdonia".[11]

Etymology

editThe earliest recorded form of the place name Criccieth in Welsh is found in Brut y Tywysogion, where reference is made to the imprisonment of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn in the 'castle of Cruceith' (Middle Welsh orthography: Kastell Krukeith).[12] The form Cruciaith was used by Iolo Goch in a famous 14th century poem addressed to Sir Hywel y Fwyall, custodian of the castle.[13]

There are a number of theories as to the meaning, but the most popular is that it comes from crug caeth: caeth may mean 'prisoner' and thus the name could mean 'prisoner's rock', a reference to the imprisonment of one of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth's sons in the castle by his brother.[14] However, caeth has the primary meaning in Middle Welsh of 'serf[s]'[15] and the name could refer to a bond community nearby. In later medieval times the settlement was also known as Treferthyr (martyr's town), probably a reference to Saint Catherine, after whom the parish church is named.[14]

The Welsh Language Commissioner gives the standard form of the name as Cricieth.[16] However, the post town, Ordnance Survey and the legal name of the community all use the spelling Criccieth.[17] The town council has the power to change the legal name of the community, or to adopt different forms of the name for use in Welsh and English language contexts.[18] The council has been petitioned to adopt the Cricieth spelling on multiple occasions, dating back to at least 1969 when the county council asked the urban district council (the town council's predecessor) to change the name, but it declined to do so. This led to a row between the two councils over various road signs the county council had already put up with the Cricieth spelling.[19][20] The town council maintained its position of using the spelling Criccieth in both Welsh and English contexts when similar requests for it to change the name were made in 1985 and 2008.[21][22]

History

editThe area around Criccieth was settled during the Bronze Age, and a chambered tomb, Cae Dyni, survives on the coast to the east of the town; it consists of seven upright stones, and there are 13 cup marks, arranged in several groups.[23] Evidence from other sites on the Llŷn Peninsula suggests that the area was colonised by a wave of Celtic settlers, who explored the Irish Sea, probably around the 4th century BC. Ptolemy calls the peninsula Ganganorum Promontorium (English: Peninsula of the Gangani); the Gangani were a tribe of Irish Celts, and it is thought there may have been strong and friendly links with Leinster.[24]

Although it is thought that Criccieth Castle was built around 1230 by Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, who had controlled the area since 1202, the first record of the building was in 1239, when the administrative centre of Eifionydd was moved from Dolbenmaen.[25]

In the later years of his life, Llywelyn turned his attention to his successor. Welsh law stipulated that illegitimate sons had equal rights with legitimate sons; Llywelyn sought to ensure that Dafydd ap Llywelyn, his legitimate offspring, would inherit Gwynedd in place of his eldest, but illegitimate, son Gruffydd. On Llywelyn's death in 1240, Dafydd sought to secure his position. Dafydd was half English and feared that his pure Welsh half-brother would be able to gather support to overthrow him. Gruffydd was held prisoner in Criccieth Castle, until he was handed over to Henry III of England in 1241, and moved to the Tower of London.[26]

Dafydd ap Llywelyn died in 1246, without leaving an heir, and was succeeded by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, his nephew. Edward I had inherited the English throne in 1272, and in 1276 declared Llywelyn a rebel. By 1277, Edward's armies had captured the Isle of Anglesey, and were encamped at Deganwy; the settlement, the Treaty of Aberconwy, forced Llywelyn to acknowledge Edward as his sovereign, and stripped him of much of his territory. Dafydd ap Gruffydd, Llywelyn's younger brother, attacked the English forces at Hawarden in 1282, setting off a widespread rebellion throughout Wales;[27] Edward responded with a further invasion of Gwynedd, during which Llywelyn was killed on the battlefield at Cilmeri.[28]

With the final defeat of Gwynedd, Edward set about consolidating his rule in Wales. Criccieth Castle was extended and reshaped, becoming one of a ring of castles surrounding Edward's newly conquered territories. A township developed to support the garrison and a charter was granted in 1284; the charter was intended to create a plantation of English burgesses who would provide food for the soldiers from the arable land behind the Dinas and the grazings on the slopes beyond.[25] Weekly markets were held on Thursdays and there were annual fairs on 25 April and 18 October, the evangelical feasts of Saint Mark and Saint Luke.[6][29]

The new administration soon proved unpopular among the native Welsh, and in 1294, Madog ap Llywelyn led a national revolt against English rule. Criccieth was besieged for several months over the winter; 41 residents sought refuge within its walls, joining the garrison of 29 men under William de Leybourne, until supplies were brought in from Ireland the following April. The following year, the castle was again used as a prison, housing captives taken in Edward's wars against Scotland.[30]

Three Welshmen who had settled in the borough, which was supposedly reserved for the English, were evicted in 1337, but times were about to change. Hywel ap Gruffydd was appointed constable of the castle in 1359, the first Welshman to hold the post. The following year came mayor of the town, holding the office for twenty years; in a poem of praise, Iolo Goch described him as "a puissant knight, head of a garrison guarding the land".[29] By 1374 eight jurymen from the borough had Welsh names.[14]

Richard II was deposed and imprisoned in 1399, and died in mysterious circumstances the following year. Opposition to the new king, Henry IV, was particularly strong in Wales and Cheshire, and in 1400 serious civil unrest broke out in Chester. Henry had already declared Owain Glyndŵr, a descendant of the Princes of Powys, a traitor, and on 16 September 1400 Owain launched a revolt. He was proclaimed Prince of Wales, and within days a number of towns in the north east of Wales had been attacked. By 1401 the whole of northern and central Wales had rallied to Owain's cause, and by 1403 villages throughout the country were rising in support. English castles and manor houses fell and were occupied by Owain's supporters. Although the garrison at Criccieth Castle had been reinforced, a French fleet in the Irish Sea stopped supplies getting through, and the castle fell in the spring of 1404. The castle was sacked; its walls were torn down; and both the castle and borough were burned. The castle was never to be reoccupied, while the town was to become a small Welsh backwater, no longer involved in affairs of state.[30] The town was described in 1847 as follows,

It is a poor straggling place, with houses built without any regard to order, and having nothing worthy of notice save the ruins of the ancient castle, which stand on an eminence jutting into the sea. The population of Criccieth in 1841 was 811.[31]

The town expanded in the 19th century with the coming of new transportation links. In 1807 a turnpike road was built from Tremadog to Porthdinllaen, which was intended to be the main port for traffic to Ireland; and with the construction of the Aberystwith and Welsh Coast Railway in 1868, the town began to develop as a Victorian seaside resort.[25]

Criccieth solicitor David Lloyd George was elected as Liberal Member of Parliament for the Caernarfon Boroughs in 1890. He was to hold the seat for 55 years, during which he was Prime Minister from 1916 to 1922, contributing greatly to victory in the First World War (he was 'the man who won the war') through brilliant administration, leadership skills and personal energy, and negotiating the ill-fated Versailles peace treaty. Before that he was one of the great welfare reformers of the 20th century, starting old age pensions and unemployment payments. His position as a leading statesman brought Criccieth national and international prominence that it had never previously enjoyed; the town still has many locations connected with Lloyd George and his family.[32]

Disaster struck Criccieth in October 1927; a great storm in the Irish Sea stopped the tidal flow, causing a double high tide. High seas and strong on-shore winds destroyed houses at Abermarchnad, the pressure of the waves punching holes through the back walls; the houses subsequently had to be demolished and the occupants rehoused.[33]

Governance

editThere are two tiers of local government covering Criccieth, at community (town) and county level: Criccieth Town Council (Cyngor Tref Criccieth) and Gwynedd Council (Cyngor Gwynedd). The town council meets at the Memorial Hall on High Street.[34]

The town forms part of the Dwyfor Meirionnydd constituency for elections to the House of Commons, and also forms part of the Dwyfor Meirionnydd constituency for the Senedd.[17]

Administrative history

editCriccieth was an ancient parish.[35] It was also the main town in the ancient commote of Eifionydd, which in 1284 was made part of the new county of Caernarfonshire under the Statute of Rhuddlan.[36] Also in 1284 the town was made a borough under a charter granted by Edward I of England. The first mayor was William de Leybourne, who was appointed constable of the castle a month after the charter was granted.[29]

It became customary for the constable of the castle to also serve as mayor ex officio, and the Town Hall (also known as the Guildhall) was built within the castle grounds.[37] A government survey of boroughs in 1835 found that the borough corporation had very few powers. The role of mayor and constable of the castle had become hereditary; in 1835 it was held by William Ormsby-Gore, who lived in Shropshire.[38]

Given its limited powers, the borough was left unreformed when the Municipal Corporations Act 1835 reformed most ancient boroughs across the country into municipal boroughs. The old corporation continued to operate, but with very few functions. In order to provide more modern forms of local government, a local government district was created under the Criccieth Improvement Act 1873, which also disbanded the old borough corporation, replacing it with an elected local board.[39][40] Any residual claim Criccieth may have had to be called a borough was extinguished under the Municipal Corporations Act 1883.[41]

Local government districts were converted into urban districts under the Local Government Act 1894. The 1894 Act also directed that parishes could no longer straddle district boundaries, and so the part of Criccieth parish outside the urban district became a separate parish called Penllyn. The urban district was extended in 1934 to take in parts of the neighbouring parishes of Penllyn and Treflys, and again in 1938 to take in part of Llanystumdwy.[42]

Criccieth Urban District was abolished in 1974 under the Local Government Act 1972. A community called Criccieth was created instead, covering the area of the abolished urban district. District-level functions passed to Dwyfor District Council, which was in turn replaced in 1996 by Gwynedd Council.[43][44]

Geography

editCriccieth is located in Eifionydd on the Cardigan Bay shore of the Llŷn Peninsula. The town is south facing and built around the rocky outcrop containing Criccieth Castle, which effectively divides the shoreline in two at this point. The East Shore has a sandy beach with a shallow area for bathing, whilst the Marine Beach, to the west, is quieter and has a number of hotels and guest houses.[45]

The rhyolitic headland on which the castle is built is strong and not easily eroded. The cliffs to each side, however, are less resistant, being made up of glacial drift, layers of boulders, stones, clay and silt which were laid down during the last ice age. Sea walls were already in existence at the time of the first Ordnance Survey map in 1891, and the west shore sea wall had been extended and groynes built by 1913. Extensive remedial work was completed in 1965, and the defences were again strengthened in 1974 and 1985. In 1995 work was started on improving the defences along The Esplanade, followed in 1997 by further work to replace the crumbling gabions below Lôn Felin.[46] Submerged forests occur in a number of places off the Cardigan Bay coastline, including Criccieth; these are deposits of peat, soil and tree remains and appear to be post-glacial coastal lagoons and estuaries, which have been flooded by rising sea levels.[47]

The town has a temperate maritime climate which is influenced by the Gulf Stream. Frost and snow are rare; the last serious snowfall, of 6 inches (15 cm), was in 1985.[45] The climate results in a luscious, green countryside and many delicate plant species grow wild; gorse flowers throughout the year.[45] One plant unusual to Criccieth is Lampranthus multiradiatus (syn. Lampranthus roseus), known locally as the Oxenbould daisy and introduced in the late 19th century by a resident of Min-y-Mor.[45]

| Climate data for Criccieth | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.9 (55.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 83.8 (3.30) |

55.9 (2.20) |

66.0 (2.60) |

53.3 (2.10) |

48.3 (1.90) |

53.3 (2.10) |

53.3 (2.10) |

73.7 (2.90) |

73.7 (2.90) |

91.4 (3.60) |

99.1 (3.90) |

94.0 (3.70) |

845.8 (33.3) |

| Source: [48] | |||||||||||||

Demography

editAt the 2001 Census, Criccieth had a population of 1,826,[1] of which 62.76% were born in Wales, whilst 32.61% were born in England.[49] 62.54% of households were owner occupied, and 25.30% were in rented accommodation.[49]

| Population change in Criccieth | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | |

| Population | 396 | 459 | 530 | 648 | 811 | 797 | 498 | 901 | 1,213 | |

| Year | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 2001 | 2011 |

| Population | 1,507 | 1,406 | 1,376 | 1,886 | 1,449 | 2,290 | 1,652 | 1,672 | 1,826 | 1,753 |

| Sources:[50][51][52] | ||||||||||

Economy

editIn the 16th century, at the bottom of Lôn Felin stood the town's mill, powered by water from a millpond near to the present level crossing and fed from the Afon Cwrt.[6]

The herring industry was important by the 19th century, with horsedrawn carts converging on Abermarchnad to transport the catch to neighbouring villages. There was also a coal yard and other storehouses by the quay, where the Afon Cwrt enters the sea. Opposite stood a lime kiln, with lime produced both for local use and export, limestone for the kiln being unloaded from ships on the quay.[6]

At the 2001 Census 54.18% of the population were in employment, whilst the unemployment rate stood at 3.81%.[49] The proportion retired accounted for 22.99% of the inhabitants. Of those employed, 23.04% worked in the wholesale and retail trades and 19.86% in hotels and restaurants.[49]

Landmarks

editCriccieth Castle dominates the town, standing on a rock overlooking Cardigan Bay. Little survives of the original building, but the outer defences are still prominent. The inner bailey contains the earliest remains, including the inner gatehouse, which has two semi-circular towers. It is thought that the original living quarters were in the south west tower, overlooking the sea, and that the square north tower supported a catapult.[53]

To the south of Y Maes stands Caffi Cwrt, an early 18th century detached stone house where the burgesses held court when rain prevented them meeting in their usual location on the bridge. The house has been owned by just two families since 1729. Two medieval strip fields to the rear, Llain Fawr (large strip) and Llain Bella (furthest strip), formed most of the smallholding of Cwrt but were lost when the railway was built. Nearby, where the slate shop now stands, was a smithy.[6]

On Penpaled Road is a cottage, Penpaled, built in 1820 on a plot lying between two enclosed meadows. The meadows, Cae'r Beiliaid (bailiff's field) and Llain y Beiliaid (bailiff's strip) were subsequently to form part of the route of both the road and the railway.[6]

Further uphill stand a 17th-century whitewashed cottage, Ty'r Felin, and Foinavon, a yellow pebble-dashed building once owned by the Bird's Custard family.[6]

Morfin, on Tan-y-Grisiau Terrace was used as an office by David Lloyd George whilst he was practising as a solicitor. Nearby, Ty Newydd, a mid-16th century house, was originally built to house the estate bailiff. Criccieth's first council houses on the adjacent Henbont Road were built on land donated to rehouse families made homeless by the 1927 storm. Three 600-year-old cottages, originally thatched, make up Wellington Terrace. They are thought to be the oldest in the town.[6]

Castle Road is within the original settlement, Yr Hen Dref, though most of the houses are Victorian. Ty Mawr, however, originally a smallholding and later a public house, dates from the 16th century, whilst on the opposite side of the street a long stone building, divided into three cottages, Porth yr Aur, Trefan and Cemlyn, dates from 1700. The Castle Bakery next door features a stained glass insertion above the shop window which depicts bakers at work. In the past nearby residents could bring their own dough to be baked in the ovens. By the castle entrance Gardd y Stocs, a small green, was home to the town's stocks, whilst the building that houses the castle information centre was part of the town's guildhall.[6]

The heart of the old town is Y Dref. It was here that the weekly market was held, and it was also the venue for numerous political meetings.[6]

Edward I granted lands north of the borough to the Bishop of Bangor, and it is thought that Gardd yr Esgob on Lôn Bach formed part of these. In the 19th century one of the town's abattoirs stood here. Tan y Graig, a house at the end of a long garden, dates from at least 1800. Three 16th century fishermen's cottages stand in Rock Terrace. Named Sea Winds, Ty Canol and Ty Isaf, they have 14th century foundations.[6]

On the green at West Parade stands a shelter donated by Margaret Lloyd George, the wife of the former prime minister.[6]

Muriau on Lôn Fel includes a group of partly 17th century farm buildings set around a square, which were converted into houses by Elizabeth Williams Ellis of Chwilog. Muriau Poethion contains an early spiral staircase going round a large inglenook fireplace. North of Pwllheli Road, several mansions are along the lane, now named Lôn Fel Uchaf. Parciau was once owned by Ellis Annwyl Owen, rector of Llanystumdwy from 1837 to 1846, whilst Parciau Mawr has a notable 19th century hay barn. Bryn Awelon was the home of David Lloyd George before the First World War, and later of his daughter Megan. Nearby, on Arfonia Terrace, is Parciau Uchaf, a farmhouse dating from 1829.[6]

Y Gorlan on Caernarfon Road formed part of the small estate of Cefniwrch Bach, a hunting lodge for Edward I at the time the castle was being built, and is thought to have been a tannery in medieval times.[6]

Ger y Maes, the end house on Holywell Terrace, is close to an ancient well, Ffynnon y Saint, which supplied much of the town's water. The house had a spring inside a cupboard, and ginger beer was manufactured and sold. The house at the opposite end of the terrace was a dairy, and to the south are the ruins of the former animal pound, where stray animals were held before being sold.[6]

The former National Westminster Bank on the High Street has step gables and is a duplicate of a building at Talgarth in Powys. On the south side of the street are a number of 19th century shops, including the Medical Hall, dating from 1875 and Siop Newydd, built in 1869.[6]

At the eastern end of the Esplanade stands the Morannedd Café, built in 1954 by Clough Williams-Ellis.[6]

Talhenbont Hall is a Grade II listed manor house. It was built in 1607 was once the home of William Vaughan. In 1642, the owner William Lloyd was arrested as a Royalist sympathiser as Cromwell's men took over the hall. In 1758 Talhenbont was the largest single owned piece of land in the district of Eifionydd. The estate was occupied by Sir Thomas Mostyn, the sixth baronet, from 1796. In 1884 the estate was split into sections to pay off debts that had crept up during the Napoleonic Wars. It is now operated as a holiday centre.[54]

Notable people

edit- Sir Llewelyn Turner (1823 at Parkia – 1903), politician, Mayor of Caernarfon, 1859 to 1870.

- David Lloyd George (1863–1945), UK Prime Minister from 1916 to 1922; grew up in the nearby village of Llanystumdwy.[55]

- Margaret Lloyd George (1864–1941) Welsh humanitarian, wife of David Lloyd George

- Robert Jones (1891-1962) mathematician and aerodynamicist, world expert on the stability of airships.

- Group Captain Leslie Bonnet (1902–1985), RAF officer, writer and originator of the Welsh Harlequin Duck.[56]

- Megan Lloyd George (1902–1966), politician, first female MP in Wales, daughter of David Lloyd George

- William George (1912–2006), poet and nephew of David Lloyd George.[57]

- Joan Hutt (1913–1985), an artist and wife of Leslie Bonnet,[58] they lived at Ymwlch from 1949.

- Ruth Martin-Jones (born 1947), a former long jumper and heptathlete, bronze medallist at the 1973 Commonwealth games

- Paul Roberts (born 1977) a Welsh former footballer with over 340 club caps

- Dyfan Dwyfor, actor who won the Richard Burton Award at the National Eisteddfod in 2004,[59] is from Criccieth.[60]

Lifeboat station

editThe Royal National Lifeboat Institution lifeboat station stands on Lôn Felin and was built in 1853, although it was known as Porthmadoc Lifeboat Station until 1892. It was closed in 1931 but reopened in 1953. It operates an Atlantic 85 lifeboat but also has a smaller Arancia lifeboat which can get into shallower parts of the Glaslyn and Dwyryd estuaries than the larger boat can reach.[61]

Transport

editCriccieth lies on the A497, the main road running through the southern Llŷn Peninsula from Porthmadog to Pwllheli. The B4411 runs north from Criccieth to join the A487 near Garndolbenmaen, giving access to Caernarfon to the north.

The town is served by Criccieth railway station on the Cambrian Coast Line between Pwllheli and Machynlleth. Trains, operated by Transport for Wales, run through to Shrewsbury, Wolverhampton and Birmingham.[62] The station, which is unstaffed, has been adopted by the local community which provides flower displays, and has engaged local artists to paint scenes of the town on the previously boarded up windows[63]

Buses are operated by Caelloi Motors and Lloyds Coaches. Caelloi Motors, of Pwllheli, operate local service 3 from Pwllheli to Porthmadog. Lloyds Caches, of Machynlleth, operate TrawsCymru service T2 from Bangor to Aberystwyth via Caernarfon, Criccieth, Porthmadog, Dolgellau and Machynlleth.

Education

editPrimary education is provided by Ysgol Treferthyr on Lôn Bach, which has 131 pupils.[64] At the last school inspection by Estyn, in 2010, 7% of pupils were entitled to free school meals and over half came from homes where Welsh was the main spoken language. Welsh is the main medium of teaching, and 94% of the pupils can speak Welsh.[65] Secondary school pupils mainly attend Ysgol Eifionydd in Porthmadog.[66]

Culture

editCriccieth is a predominantly Welsh speaking community, with 64.2% of residents aged three and over being able to speak the language according to the 2011 Census.[67]

The Memorial Hall, fronting Y Maes, is a venue for concerts, dramas and other community events and the main venue during the annual Criccieth Festival. It was designed by Morris Roberts of Porthmadog in a fusion of the art deco and arts and crafts architectural styles and completed in 1925, the foundation stone having been laid in 1922 by David Lloyd George.[6]

The construction of Criccieth Library on the High Street was financed by Andrew Carnegie. A plaque inside the doorway commemorates local historian Colin Gresham.[6] Among the services provided is free broadband access.[68]

The National Eisteddfod was held in Criccieth in 1975, and a new housing estate, Gorseddfa marks the place where the Gorsedd stones then stood.[6]

The Brynhir Arms on the High Street dates from 1631. Originally a single storey farm building, it was extended in 1840 to serve the new turnpike road.[6]

The Lion Hotel, an old coaching inn, was built on Y Maes in 1731. It was here that the town's councillors would retire after their meetings in Cwrt.[6]

Several of the town's hotels, including the Marine Hotel on Min-y-Mor and the Caerwylan Hotel on Min-y-Traeth, date from the period after Porthmadog's new harbour was developed in 1811, when prosperous sea captains invested in properties where their wives could provide accommodation during the summer months.[6]

An inn had reputedly existed on the site of the George IV Hotel in 1600, but the present building on the High Street dates from 1830, shortly after the turnpike opened. In the 1920s the hotel boasted that it generated its own electricity, and, for a fee, it offered a fire and private bath in guests' rooms. Servants could stay at reduced rates when accompanying their masters.[6]

Clwb Cerdd Dwyfor stages performances at the Holiday Club Hall, ranging from traditional folk to opera and chamber music.[45]

Côr Eifionydd, a mixed voice choir, was formed in 1986 to compete in the National Eisteddfod at Porthmadog the following year. Conducted by Pat Jones, originally from Newcastle Emlyn, the choir has won a number of first prizes at the National Eisteddfod. They have toured internationally and have sung in the International Choral Festival in Paris.[69]

It used to be the custom, on Easter Sunday morning, for keys or pins to be thrown into Ffynnon Fair as an offering to Saint Catherine.[70]

The town features in Welsh Incident, a humorous poem published in 1950 by Robert Graves, which tells of the mysterious creatures that supposedly, one Tuesday afternoon, "... came out / From the sea caves of Criccieth yonder."[71] It is also the subject of Shipwrecked Mariners, a painting by English Romantic landscape painter Joseph Mallord William Turner; the painting uses his sketch of Criccieth Castle but, although the rock is depicted correctly, the building is a mirror image.[72]

There is a local legend that a piper named Dic, and two fiddlers named Twm and Ned, were once lured into a nearby cave by fairies. They were not seen again, but their music could still occasionally been heard coming from the cave.[73]

Religion

editReligion has been an important part of Criccieth's life since early days, and around 1300 St Catherine's Parish Church was built on what is thought to be the site of an early religious foundation. As the town developed so did the church, and in 1500 an extra nave was added.[25] The church was restored in 1869 by Henry Kennedy and Gustavus O'Donoghue of Bangor[74] It contains wooden panelling made from old box pews and a communion table dating from the 17th century. On the wall is a list of rectors stretching back to 1301. In the graveyard, the oldest stone commemorates the death in 1688 of Robert Ellis who was Groom of the Privy Chamber in Ordinarie to Catherine of Braganza, the wife of Charles II. Outside the west door is a sundial dating from 1734 with distances to ports in all directions.[6]

In 1749 St Catherine's was one of the buildings visited by Griffith Jones's Circulating School. Out of a population of 600, 543 illiterates were taught to read so that they would be able to understand the Bible.[6]

The nearby Rectory was built in 1831 by John Jones, son of the then rector Owen Jones, who had offered to have the house built if his son could succeed to the position. However, Erasmus Parry, rector from 1863 to 1884, was the first to officially live there.[6]

St Deiniol's Church was completed in 1887 by the Chester architects Douglas & Fordham.[75] Built as a chapel of ease for St Catherine's, it was financed by the Greaves family for the use of English speaking visitors as services at the parish church were held in Welsh. It eventually closed in 1988, its pipe organ being transported to Sydney in Australia.[6]

By the 19th century Wales was a predominantly nonconformist country, and this pattern was mirrored in Criccieth with the construction of a number of dissenting chapels. The Congregationalists had met on Castle Hill but 1886 saw the building of Jerusalem Congregational Chapel on Cambrian Terrace.[6]

Capel Uchaf on Caernarfon Road was built in 1791 by the Scottish Baptists. In 1841 the congregation broke away to become Particular Baptists, followers of Alexander Campbell and the Disciples of Christ. David Lloyd George's uncle often preached here and it was from the steps opposite, leading down into the Afon Cwrt, that the future prime minister was baptised. 1886 saw the Particular Baptists move to their new home at Berea on Tan-y-Grisiau Terrace, and in 1939 they joined the Mainstream Baptists.[6]

The Calvinistic Methodists originally met at Tan y Graig on Lôn Fach but moved to Tal Sarnau, a house on the site of the Memorial Hall. From here they moved again, to a site on the High Street, rapidly outgrowing the small chapel. The neo-classical Capel Mawr was built on the same site in 1813. A second chapel, Capel y Traeth on Penpaled Road, with a notable porticoed facade, was built at a cost of £2,040 in 1895 by Owen Roberts of Porthmadog. Previously known as Capel Seion, it was renamed in 1995 when the congregation merged with that of Capel Mawr, reuniting the two congregations that had separated in 1889.[6]

Salem Methodist Chapel was built on Salem Terrace in 1901. It is now a chapel of rest.[6]

Roman Catholics worship at the Church of the Holy Spirit on Caernarfon Road,[6] whilst Criccieth Family Church meets at the Holiday Club Hall on Lôn Ednyfed.[76]

For over a hundred years community hymn singing has taken place on Sunday evenings on the small green at Abermarchnad, the site of the old market of the original fishing village.[6]

At the 2001 census 82.19 per cent of the population claimed to be Christian, whilst 12.40 per cent stated that they had no religion.[49]

Sport

editCriccieth Tennis Club can claim to be one of the oldest clubs in existence today. It began in 1882 in the grounds of Parciau Mawr and transferred to its present site in 1884. It was first affiliated to the Lawn Tennis Association in 1896. Fifty-one open tournaments were held up to 1939, with players competing for the North Wales Championships.[77] Notables who played here[citation needed] included John Boynton Priestley, the novelist, playwright and broadcaster; Frank Riseley who partnered Sydney Smith and won the Men's Double Championship at Wimbledon in 1902 and 1906; his brother Bob Riseley who was on the Wimbledon Committee of Management for many years; Dodd and Mellet of South Africa; Dorothy Round Little who was Ladies' Singles Champion at Wimbledon in 1934 and 1937 and Mixed Doubles Champion in 1934, 1935 and 1936; Commander Philip Glover, Royal Navy champion; Thelma Cazalet-Keir, the Conservative feminist politician; Alan Davies; Duncan Macaulay, who was Secretary of the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club from 1946 to 1963; and Megan Lloyd George, the Liberal Party's Deputy Leader from 1949 to 1952.

Golf started in Criccieth with a few holes on Caerdyni Hill, but in 1906 Criccieth Golf Club opened.[78] It was an undulating nine-hole course on natural terrain with views of the coast and the mountains of Snowdonia. The penultimate hole was a challenging par 4 with a green 75 feet (23 m) above the tee, whilst the finishing hole was just 100 yards (91 m) long with the green 100 feet (30 m) below the tee.[79] The club holds the distinction of having three British prime ministers, Bonar Law, David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, play the course on the same day.[80] It closed on New Year's Eve, 2017.[81]

The town is a popular venue for sea anglers. From the East Shore, bass, dogfish, mackerel and whiting can be caught. The Stone Jetty, in addition, is a good spot for conger, pollock and wrasse dabs, whilst bass, dogfish, mackerel, pollock and whiting can all also be found from the Marine Beach.[82]

Criccieth, Llanystumdwy and District Angling Association, formed in 1927, controls the fishing rights on 8 miles (13 km) of the Afon Dwyfor and Afon Dwyfach. Each year between 2,000 and 3,000 sea trout and 30 to 40 salmon are caught;[83] the association runs a hatchery where between 8,000 and 10,000 sea trout are reared annually.[84] Gloddfa Lake, a disused quarry pool on Criccieth Golf Course, is a location for coarse fishing, with catches of rudd, roach and eels.[85]

Bathing is popular, particularly on the East Shore, which is sandy and has a safe shallow area for children.[45] At the eastern end is a rocky area with rock pools exposed at low tide.[86] Graig Ddu (English: Black Rock) marks the boundary with Black Rock Sands. The Marine Beach to the west of the castle is pebbly.[87] The water quality prediction is "good" and in 2009 both beaches were awarded a yellow flag seaside award.[88][89][90][91][92]

Surfing is possible at all stages of the tide, but there is a fairly exposed beach break that does not work very often. It is particularly flat in summer. Most of the surf comes from groundswells and the best swell direction is from the southwest, the beach break providing left- and right-handers. Offshore winds blow from the north-northeast.[93]

Crown green bowls is played at Criccieth Bowling Club, and there is a miniature golf course nearby.[94]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Census 2001". Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ "Town/electoral ward population 2011". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Visit Wales : Criccieth Accommodation".[dead link]

- ^ "Cadw : Criccieth Castle". Archived from the original on 17 November 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ Cadwalader's Ice Cream : About Us

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Eira and James Gleasure, Criccieth : A Heritage Walk, 2003, Cymdeithas Hanes Eifionydd Archived 29 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Wales, 28 pages

- ^ "CRICCIETH". www.ccbsweb.force9.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ "Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru : Eisteddfod Locations". Archived from the original on 23 May 2011.

- ^ "Fairtrade Foundation : Fairtrade Towns". Archived from the original on 1 February 2010.

- ^ Criccieth in Bloom : Trophies[permanent dead link]

- ^ "CRICCIETH". www.ccbsweb.force9.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 November 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ Thomas Jones (ed.), Brut y Tywysogyon. Peniarth MS. 20 (University of Wales Press, 1941), page 197.

- ^ D.R. Johnston (editor). Gwaith Iolo Goch (University of Wales Press, 1988), poem II.37.

- ^ a b c "British Broadcasting Corporation : Criccieth's History".

- ^ Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru (University of Wales Dictionary), vol. I, p. 385.

- ^ "Standardised Welsh Place-names list". Welsh Language Commissioner. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "Local Government Act 1972: Section 76", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1972 c. 70 (s. 76), retrieved 26 November 2024

- ^ "County would like 'Cricieth'". Daily Post. Liverpool. 29 December 1969. p. 7. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ Wynne Jones, Ivor (6 June 1970). "Place-name pundits at it again". Daily Post. Liverpool. p. 1. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "The C comes in to split a town". Daily Post. Liverpool. 18 February 1985. p. 17. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "Red letter day for place names?". BBC News. 10 September 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ Clifton Antiquarian Club : Cupmarks Discovered on the Cae Dyni Chambered Monument Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-20

- ^ Richard Sale, Best Walks in North Wales, 2006, Frances Lincoln, London, 300 pages, ISBN 978-0-7112-2423-0

- ^ a b c d Criccieth Visitors' Map and Brief History, 2002, Cymdeithas Hanes Eifionydd Archived 29 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Wales

- ^ The University of Sydney Library : Languishing in the Footnotes : Women and Welsh Medieval Historiography Retrieved 2009-08-19

- ^ Princes of Gwynedd : Llywelyn ap Gruffydd Archived 19 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-19

- ^ Cilmeri : Death of Llywelyn Archived 9 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-19

- ^ a b c "Cymdeithas Hanes Eifionydd : The Town and Borough of Criccieth". Archived from the original on 7 October 2011.

- ^ a b Criccieth Business and Shop Alert : Criccieth CastleRetrieved 2009-08-19

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.III, (1847), London, Charles Knight, p.1,017

- ^ Number 10 : The Official Site of the Prime Minister's Office : History and Tour : David Lloyd George Archived 25 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-19

- ^ "Cymdeithas Hanes Eifionydd : Storm". Archived from the original on 7 October 2011.

- ^ "Criccieth Town Council". Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ "Cricieth Ancient Parish / Civil Parish". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ Breverton, Terry (2009). Wales: A Historical Companion. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445609904. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ "Criccieth - The Old Town Hall". People's Collection Wales. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ Parliamentary Papers. 1838. p. 25. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "Criccieth Improvement Act 1873 (36 & 37 Vict. c.ccxliii)". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ Report of the Commissioners appointed to inquire into Municipal Corporations not subject to the Municipal Corporations Acts. 1880. p. 142. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ Municipal Corporations Act 1883 (46 & 46 Vict. Ch. 18) (PDF). 1883. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "Great Britain Dep through time | Census tables with data for the Country". www.visionofbritain.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "Local Government Act 1972", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1972 c. 70, retrieved 6 October 2022

- ^ "Local Government (Wales) Act 1994", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1994 c. 19, retrieved 9 October 2022

- ^ a b c d e f "EE". EE.

- ^ Coventry City Council : Learning Gateway : Coastal Management : Criccieth[permanent dead link]

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales : Maritime Archaeology in Wales Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-20

- ^ The Weather Channel : Criccieth Weather Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-17

- ^ a b c d e "Local statistics - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk.

- ^ "Cricieth AP/CP through time | Population Statistics | Total Population". www.visionofbritain.org.uk.

- ^ "Cricieth UD through time | Population Statistics | Total Population". www.visionofbritain.org.uk.

- ^ "HISTPOP.ORG - Error". www.histpop.org.

- ^ The Heritage Trail : Criccieth Castle Archived 12 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-20

- ^ "Wedding Venue North Wales & Self Catering Cottages, Snowdonia". www.talhenbonthall.co.uk.

- ^ Buckle, George Earle (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 31 (12th ed.).

- ^ "Leslie Bonnet", by Frank Dancaster. THE OLD LADY, June 1986.

- ^ "Lloyd George nephew dies, aged 94". BBC News. 20 November 2006.

- ^ "Obituary:Mrs J.V. Hutt. Caernarfon and Denbigh Herald, 1 February 1985.

- ^ "Chichester Festival Theatre : Dyfan Dwyfor". Archived from the original on 6 January 2010.

- ^ Price, Karen (10 May 2009). "Welsh actors on working for Royal Shakespeare Company". walesonline.

- ^ "Criccieth station history". RNLI. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Arriva Trains Wales : Cambrian Lines". Archived from the original on 28 July 2009.

- ^ Criccieth in Bloom : Current Projects[permanent dead link]

- ^ "My Local School". mylocalschool.wales.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ "A report on Ysgol Treferthyr". Estyn. Retrieved 13 April 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Estyn" (PDF). www.estyn.gov.wales. Archived from the original on 7 October 2006.

- ^ "2011 Census results by Community". Welsh Language Commissioner. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ "Cyngor Gwynedd : Criccieth Library". Archived from the original on 8 June 2011.

- ^ Côr Eifionydd : History Archived 22 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Rhŷs, Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx: Volume 2, 1901, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 420 pages

- ^ Old Poetry : Welsh Incident

- ^ British Broadcasting Corporation : Criccieth's History Retrieved 2009-08-20

- ^ Ash, Russell (1973). Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain. Reader's Digest Association Limited. p. 384. ISBN 9780340165973.

- ^ "The Incorporated Church Building Society : Church Plans Online : St Catherine". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ Hubbard, Edward (1991). The Work of John Douglas. London: Victorian Society. ISBN 0-901657-16-6.

- ^ "Criccieth Family Church". Archived from the original on 29 October 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ "Cymdeithas Hanes Eifionydd : Lawn Tennis". Archived from the original on 7 October 2011.

- ^ "Cymdeithas Hanes Eifionydd : Golf". Archived from the original on 7 October 2011.

- ^ Criccieth Golf Club : The Course

- ^ Criccieth Golf Club : Welcome

- ^ "Criccieth Golf Club, Gwynedd. (1905 - 2017)". www.golfsmissinglinks.co.uk.

- ^ "Angling Wales". Archived from the original on 21 October 2001. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ Angling Wales : Salmon and Sea Trout : River Dwyfor Archived 21 October 2001 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-20

- ^ Criccieth, Llanystumdwy and District Angling Association : Who We Are Archived 20 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2009-08-20

- ^ "Angling News : Fishing Venue Guide : Gwynedd". Archived from the original on 19 April 2009.

- ^ "Visitors Guide". www.criccieth.co.uk.

- ^ "Beaches". www.criccieth.co.uk.

- ^ "Environment Agency : Water Quality Classification Predictions for Bathing Waters in England and Wales under the Revised Bathing Water Directive" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2008.

- ^ Williams, Sally (30 April 2009). "Number of top quality beaches falls". walesonline.

- ^ "Keep Wales Tidy : Investment Brings Summer Joy" (PDF).

- ^ "Keep Wales Tidy : Seaside Award Resort Beach Criteria" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2007.

- ^ Environment Agency : Bathing Water Quality : Criccieth : 2008[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Criccieth Surf Forecast and Surf Reports (Wales - Lleyn, UK)". www.surf-forecast.com.

- ^ "Bowls Club : Criccieth Bowling Club". Archived from the original on 8 November 2007.

External links

edit- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). 1911.