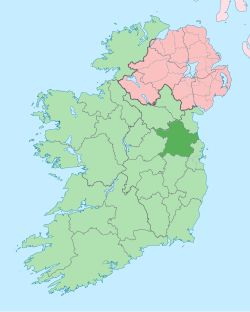

County Meath (/miːð/ MEEDH; Irish: Contae na Mí or simply an Mhí, lit. 'middle') is a county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Ireland, within the province of Leinster. It is bordered by County Dublin to the southeast, Louth to the northeast, Kildare to the south, Offaly to the southwest, Westmeath to the west, Cavan to the northwest, and Monaghan to the north. To the east, Meath also borders the Irish Sea along a narrow strip between the rivers Boyne and Delvin, giving it the second shortest coastline of any county. Meath County Council is the local authority for the county.

County Meath

Contae na Mí | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: The Royal County | |

| Motto(s): Irish: Tré Neart le Chéile "Stronger Together" | |

| Anthem: "Beautiful Meath" (unofficial) | |

| |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| Region | Eastern and Midland |

| History | Date |

| Kingdom of Meath | Antiquity |

| Lordship of Meath | 1172 |

| Shired | 1297 |

| Division of Meath | 1542 |

| County town | Navan (1898–) Trim (1297–1898) |

| Government | |

| • Local authority | Meath County Council |

| • Dáil constituencies | |

| • EP constituency | Midlands–North-West |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,342 km2 (904 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 14th |

| Highest elevation | 276 m (906 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 220,826 |

| • Rank | 8th |

| • Density | 94/km2 (240/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166 code | IE-MH |

| Vehicle index mark code | MH |

| Website | Official website |

| |

Meath is the 14th-largest of Ireland's 32 traditional counties by land area, and the 8th-most populous, with a total population of 220,826 according to the 2022 census.[2] The county town and largest settlement in Meath is Navan, located in the centre of the county along the River Boyne. Other towns in the county include Trim, Kells, Laytown, Ashbourne, Dunboyne, Slane and Bettystown.

Colloquially known as "The Royal County", the historic Kingdom of Meath was the seat of the High King of Ireland and, for a time, was also the island's fifth province. Ruled for centuries by the Southern Uí Néill dynasty, in the late 1100s the kingdom was invaded by the Anglo-Norman conqueror Hugh de Lacy, who ousted the Uí Néill and established himself as the Lord of Meath. This lordship gradually diminished in size before being formally shired as County Meath in 1297, which was further sub-divided into Meath and Westmeath in 1542. The county took its present boundaries in 1977, when much of Drogheda was transferred to County Louth.[3]

Meath has an abundance of historical sites, including the Hill of Tara, Hill of Slane, Newgrange, Knowth, Dowth, Loughcrew, the Abbey of Kells, Trim Castle and Slane Castle. The county was also the site of the seminal Battle of the Boyne, which was fought near Oldbridge in 1690, ending in the defeat of James II and his flight to France. It is the only county in Leinster to have Gaeltacht regions, at Ráth Chairn and Baile Ghib, and is also one of only two counties outside of the west of Ireland to have an official Gaeltacht (the other being County Waterford).

Geography and subdivisions

editMeath is the 14th-largest of Ireland's 32 counties by area, and the eighth-largest in terms of population.[4] It is the second-largest of Leinster's 12 counties in size, and the third-largest in terms of population. Meath borders seven counties – Dublin and Louth to the east, Westmeath and Offaly to the west, Kildare to the south, and Cavan and Monaghan to the north. Meath's coastline stretches for roughly 20 km (12 mi) along the Irish Sea between the Boyne and Delvin rivers, making it the second shortest coastline of any coastal county.[5] The county town, Navan, is the largest settlement in Meath, and is situated on the River Boyne in the middle of the county. Navan is approximately 50 km (31 mi) from Dublin and 140 km (87 mi) from Belfast.

Physical geography

editOwing to the fertile agricultural plains along the Boyne valley, which dominate the county, Meath's landscape is largely rural in nature. However, it is also one of the most densely populated counties in Ireland, with a population density of 94 people per km2. Centuries of exhaustive harvesting and reclamation for agriculture have severely reduced the extent of bogland in the county, especially in comparison to the neighbouring Midland counties. However, small areas of bogland survived, such as Jamestown Bog, Girley Bog and Killyconny Bog, and are currently protected as either Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) or Natural Heritage Areas (NHAs).[6]

The River Boyne, at 112 km (70 mi) in length, is Meath's dominant geographic feature and is synonymous with the county, having defined its history and culture over millennia. The two most prominent tributaries of the Boyne are the Leinster Blackwater, which has its source in Cavan and flows south for 68 km (42 mi) before joining the Boyne at Navan, and the Enfield Blackwater, which has its source in Kildare and flows north for 25 km (16 mi) before joining the Boyne at Donore. In the east of the county, both the River Nanny and the Delvin River flow to the Irish sea, with the latter demarcating the border with County Dublin.

As of 2017, there is a total of 13,326 ha (32,929 acres) of forest cover in the county, representing 5.7% of the total land area. This is an increase from just 11,200 ha (27,676 acres) (4.8%) in 2006. Nevertheless, Meath is Ireland's third-least forested county and remains well below the national average of 11% forest cover.[7] Historically, Meath was extensively forested, but experienced a near total deforestation between the 16th and 18th centuries. Although it has rebounded in recent years, the low forest cover compared to other counties can be explained by the lack of a significant commercial forestry industry within the county. Meath is one of the smallest contributors to the national timber supply, and over two-thirds of Meath's forests are broadleaf – the highest of any county – as opposed to more commercially viable conifers. Additionally, three-quarters of forests within the county are privately owned.[8]

Climate

editUnder Köppen climate classification, Meath experiences a maritime temperate oceanic climate with cool winters, mild humid summers, and a lack of temperature extremes. Met Éireann records the climate data for Meath from their station at Dunsany, situated 83 m (272 ft) above sea level. The average maximum January temperature is 7.3 °C (45 °F), while the average maximum July temperature is 19.6 °C (67 °F). On average, the sunniest months are May and June, while the wettest month is October with 87 mm (3 in) of rain, and the driest month is June with 67 mm (3 in).[9] Humidity is high year-round and rainfall is evenly distributed throughout the year. A number of synoptic stations which record rainfall are located throughout the county. The driest parts of the county are in the east and south, while the wettest are in the west. Julianstown near the east coast receives 781 mm (31 in) of rainfall per year, while Oldcastle in the west receives 1,002 mm (39 in). The annual precipitation at Dunsany is 847 mm (33 in).

Snow showers generally occur between November and March, but prolonged or heavy snow events are rare. Although frost is common in the central and western areas of the county, temperatures typically fall below 0 °C (32 °F) on just a few days per year. The lowest ever temperature in Meath was recorded in December 2010, at −13.3 °C (8 °F).[10] Summer daytime temperatures range between 15 °C (59 °F) and 22 °C (72 °F), with temperatures rarely going beyond 25 °C (77 °F). As with rainfall, the sunniest areas of the county are located along the coast. The climate gets progressively duller and wetter inland due to the convective development of clouds over land.

Geology

editThe county's geological landscape is predominantly made up of Lower Carboniferous limestone, which underlies approximately 75% of the county. These were laid down following the erosion of mountain ranges which formed due to the closure of the Iapetus Ocean. The eroded mountains became basins in which limestone sediments and carbonate mud were deposited. The oldest rocks in the county are Ordovician in age and are found in thin layers near Slane and at Stamullen, while the youngest rocks are of Paleogene age, and were formed as a result of volcanic activity. These are found in small dykes and sills throughout the county. Crustal stretching beneath Ireland during the Carboniferous allowed fluids to infiltrate through faults in the rock, and extensive mineralisation occurred.[11] Most notably, zinc-bearing Sphalerite and lead-bearing Galena were deposited in vast quantities, giving Ireland the highest concentration of zinc per square kilometre on Earth.[12] The ubiquity of these minerals gave rise to the term "Irish-type" lead-zinc deposits, which is a descriptive term for lead-zinc deposits hosted in carbonate rocks.[13]

Meath's landscape was shaped during the Last Glacial Period, which ended 11,700 years ago. The soils of the county are mostly derived from glacial till, consisting of a mix of clay, sand and gravel which were deposited by glacial melt-water. In the north of the county near the border with Cavan, a small series of drumlins were formed from boulder clay. Loughs typically form in between the poorly-drained inter-drumlin areas, however unlike in neighbouring Cavan and Westmeath, Meath has no sizable loughs, other than Lough Sheelin, on which the county shares a small coastline in its westernmost tip.[14]

Meath is largely flat and much of the county lies below 100 m (330 ft) above sea-level. The minor hills in the far west of the county at Loughcrew, and in the north at Carrickleck are the only upland areas of any significance. Slieve na Calliagh, at just 276 m (906 ft) in height, is the highest point in the county, making it the second lowest county top in Ireland. Carrickleck Hill, near the Cavan border, is the second highest peak in Meath, at 173 m (568 ft).[15] The Hill of Tara is located south of Navan and, although just 155 m (509 ft) in height, is the most prominent feature in the local topography, commanding a panoramic view of the surrounding area.

Baronies

editThere are eighteen historic baronies in the county.[16] While baronies continue to be officially defined units, they are no longer used for many administrative purposes, and the barony boundaries in County Meath which continuously changed from the 16th to 19th centuries were last finalised in 1807. Their official status is illustrated by Placenames Orders made since 2003, where official Irish names of baronies are listed under "Administrative units". The largest barony in Meath is Kells Upper, at 49,552 acres (201 km2), and the smallest barony is Dunboyne, at 16,781 acres (68 km2).

- Deece Upper (Déise Uachtarach)

- Deece Lower (Déise Íochtarach)

- Duleek Upper (Damhliag Uachtarach)

- Duleek Lower (Damhliag Íochtarach)

- Dunboyne (Dún Búinne)

- Fore (Baile Fhobhair)

- Kells Upper (Ceanannas Uachtarach)

- Kells Lower (Ceanannas Íochtarach)

- Lune (Luíne)

- Morgallion (Machaire Gaileang)

- Moyfenrath Upper (Maigh Fionnráithe Uachtarach)

- Moyfenrath Lower (Maigh Fionnráithe Íochtarach)

- Navan Upper (An Uaimh Uachtarach)

- Navan Lower (An Uaimh Íochtarach)

- Ratoath (Ráth Tó)

- Skreen (An Scrín)

- Slane Upper (Baile Shláine Uachtarach)

- Slane Lower (Baile Shláine Íochtarach)

Civil parishes and townlands

editTownlands are the smallest officially defined geographical divisions in Ireland, there are approximately 1,634 townlands in the county. Historic town boundaries are registered as their own townlands and much larger than rural townlands which, within County Meath, are typically small in size, ranging from just 1 acre to 2,681 acres, with the average size of a townland in the county (excluding towns) being 356 acres.

Towns and villages

editEuropean statistical region

editFor statistical purposes at EU level, the county is part of the Mid-East Region – a NUTS III entity – which is in turn part of the level II NUTS entity – Eastern and Midland Region.

Governance and politics

editLocal government

editMeath County Council is the local authority governing County Meath. It has 40 councillors, and the county is divided into divided into six local electoral areas, each of which also forms a municipal district: Ashbourne (6), Kells (7), Laytown–Bettystown (7), Navan (7), Ratoath (7) and Trim (6).[17][18]

Fine Gael currently hold 11 seats, Fianna Fáil hold 9, Sinn Féin hold 6, Aontú hold 2, and the Social Democrats hold 1. There are 11 independent councillors. Council elections are held every 5 years, with the next election due to be held in June 2029. The 2024 Meath local elections had a voter turnout of 48.0%, a very slight decrease of 0.1% on the 2019 election. The highest turnout was at Kells (55.0%) and the lowest was at Trim (43.9%).[19]

The council has three representatives on the Eastern and Midland Regional Assembly.[20]

The county town is Navan, where the county hall and government are located, although Trim, the former county town, has historical significance and remains a sitting place of the circuit court.

| Party | Seats | FPv% | % Change since 2019 | Seat Change since 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine Gael | 11 | 24.4% | 5.2% | 1 | |

| Fianna Fáil | 9 | 20.9% | 4.4% | 3 | |

| Sinn Féin | 6 | 13.4% | 3.5% | 3 | |

| Aontú | 2 | 6.4% | 1.6% | 1 | |

| Social Democrats | 1 | 1.6% | 0.6% | ||

| Labour | 0 | 1.8% | 0.6% | 1 | |

| Independent | 11 | 28.0% | 4.1% | 1 | |

Former districts

editCounty Meath was divided under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 into the rural districts of Ardee No. 2, Dunshaughlin, Kells, Meath, Navan, Oldcastle, Trim, and Edenderry No. 3, and the urban districts of An Uaimh (Navan), Ceannanus Mór (Kells), and Trim.[21] The rural districts were abolished in 1925.[22] The urban districts became town councils in 2002.[23] All town councils in Ireland were abolished in 2014.[24]

National elections

editCounty Meath is within four Dáil constituencies:[25]

- Cavan–Monaghan – comprises the entirety of counties Cavan and Monaghan, with a small portion of northern County Meath;

- Louth – comprises the entirety of County Louth, with the electoral divisions of Julianstown and St. Marys (Part) in County Meath;

- Meath East – lies entirely within the borders of the county;

- Meath West – comprises the western portion of the county and includes a part of the neighbouring county of Westmeath;

From 1923 to 1937, and again from 1948 to 2007, there was one Meath constituency. From 1937 to 1948 the county was within the Meath–Westmeath constituency. Between 1923 and 2007 a total of 31 general elections and by-elections were held. Following the demise of Cumann na nGaedheal in the 1930s, national politics in the Meath and Meath–Westmeath constituencies was dominated by Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and Labour Party. During those years, the Meath and Meath–Westmeath constituencies returned a total of 106 TDs to Dáil Éireann, of which 54 were from Fianna Fáil, 34 from Fine Gael and 11 from Labour; with Cumann na nGaedheal and the Farmers' Party returning 6 and 1 TDs respectively in the 1920s and 1930s.[26] No other party would win a Dáil seat in Meath until 2011, when Peadar Tóibín was elected to Meath West for Sinn Féin.

Meath East and Meath West return 6 TDs to the Dáil. In the most recent general election in 2020, Sinn Féin won 2 of the 6 seats, Fine Gael won 2, and Fianna Fáil and Aontú both won 1 seat each. The voter turnout at the 2016 general election was 61.5% in Meath West, and 63.4% in Meath East.

European elections

editThe county is part of the 4-seat Midlands–North-West constituency for elections to the European Parliament.

History

editThe county is colloquially known by the nickname "The Royal County", owing to its history as the seat of the High King of Ireland.[27][28][29] It formed from the eastern part of the former Kingdom of Mide but now forms part of the province of Leinster. Historically, the kingdom and its successor territory the Lordship of Meath included all of the counties Meath, Fingal and Westmeath as well as parts of counties Cavan, Longford, Louth, Offaly and Kildare. The seat of the High King of Ireland was at Tara. The archaeological complex of Brú na Bóinne in the north-east of the county is 5,000 years old and is a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site.[30]

Pre-history

editThe earliest known evidence of human settlement in the county is the Mesolithic flints found at Randalstown north of Navan, which were uncovered during the construction of the tailings pond for Tara Mines in the 1970s. These flints have been dated to 9,500 BC and are one of the earliest traces of pre-historic humans in Ireland. The excavation site at Randalstown also revealed other evidence of hunter-gatherer society, such as a fulacht fiadh and mounds of burnt soil and stone.[31]

Farming was established in the area during the Neolithic period. This provided a surplus of time and resources which was spent constructing great stone monuments to the dead, such as passage graves, court cairns and wedge tombs. There are hundreds of surviving examples of these dotted across the landscape, however, the most famous Neolithic monuments in Ireland are those at Brú na Bóinne – Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth. These tombs were constructed prior to 3,000 BC making them older than Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids. The site is believed to have been of religious significance and is decorated with megalithic art. Newgrange, the largest pre-historic tomb in Ireland, is most famous for its alignment with the equinoxes, when sunlight shines through a 'roofbox' and floods the inner chamber.[32][33] In constructing the tomb the early settlers displayed an advanced knowledge of astronomy and a calendar system. However, a writing system would not be developed until the 1st century BC, with the emergence of Ogham.

The arrival of the Celts to Ireland around 500 BC heralded the beginning of the Iron Age and the establishment of most of what would define Gaelic Irish culture for millennia; including Primitive Irish, Irish mythology, Celtic paganism and an early form of the Gaelic calendar. The ancient monuments of the Boyne Valley were assimilated into Celtic culture and mythology, with Cú Chulainn said to have been conceived at Newgrange. Furthermore, tradition states that Sláine mac Dela, of the Fir Bolg, cleared the forest at Brú na Bóinne and built the monuments, becoming the first High King of Ireland. It was during the Celtic period that Meath was divided into 8 túatha, the primary political unit of Celtic Ireland. The túatha were independent petty kingdoms ruled by a chief who was elected by members of their extended family.

Early Christian period (400–1169)

editKingdom of Meath

editDue to a lack of extensive written historical records prior to the 5th century AD, the early history of Meath is murky and largely mythologised. Irish legend purports that the title of "High King of Ireland" stretches back millennia, however, it is today known that the Hill of Tara did not become a seat of power until the early centuries AD.[34] In the 400s, Niall of the Nine Hostages, King of the Uí Néill, conquered southward from Ulster and established a kingdom in Meath. As was commonplace in Ireland at the time, the achievements of Niall and his sons were propagandised and mythicised by bards to such an extent that much of what is known about them is considered fictional. Nevertheless, the dynasty of the Uí Néill had become firmly established in the centre of Ireland and they proclaimed themselves the Kings of Tara and Kings of Uisnech.[35] The Uí Néill dynasty subsequently divided into two septs, the Northern Uí Néill who remained in Ulster, and the Southern Uí Néill who now ruled over several small, disjointed kingdoms established throughout modern-day Meath, Westmeath and Dublin.

Following the split, a series of internecine conflicts erupted between members of the Uí Néill septs. The feud was eventually resolved, and as part of the resolution, it was decided that the position of King of Tara would alternate between the northern and southern Uí Néill septs. The title alternated between the two septs for over 500 years, with every second king travelling south from Ulster for an inauguration ceremony at Tara.[36] By 740, Domnall Midi of the Clann Cholmáin dynasty, the most powerful branch of the southern Uí Néill, had conquered or subdued all neighbouring clans in Meath, and the Uí Néill were recognised as their suzerain. Domnall was now in possession of both Tara, the seat of the Uí Néill, and the Hill of Uisneach, which held symbolic significance as the geographical centre of Ireland. Having secured his power in the heart of the island, Domnall now presided over a unified Kingdom of Mide (Meath), a name derived from the Old Irish meaning "middle".[37]

The first annalistic mention of a "High King of Ireland" or "Ard-Rí" was Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid, King of Mide, who died in 862 AD, having achieved many victories against both the Norse and the kingdoms of Ulster. Later historians would retroactively apply the title of "High King" to the earlier Kings of Tara, although there were no contemporary references to either the Kings of Tara or Mide being referred to as Ard-Rí prior to the 9th century.[38] During the reign of Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill in the 970s, the fort of Dun-na-Scia near Lough Ennell became the permanent royal residence, thereby creating two seats of power within the kingdom – one for the High King and one for the King of Mide.[39]

In the late 10th century, the Dalcassians to the south, led by Brian Boru, consolidated their hold over Munster, with Boru establishing himself as King of Munster. The ascendancy of this longtime rival kingdom posed a serious threat to High King Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, so the two leaders met at Clonfert in 997 and agreed upon a truce, whereby Boru was granted overlordship of the southern half of the island. The Kingdom of Leinster immediately rebelled against Boru and allied with the Norse Kingdom of Dublin. Mide and Munster formed a defensive alliance and, after a series of campaigns throughout 998–999, crushed the forces of Leinster and Dublin, which both became vassals of Munster.

Boru now believed that Munster was the most powerful kingdom in Ireland and therefore he, and not Máel Sechnaill, should be the High King. Máel Sechnaill's claim to the kingship was challenged by Boru in 1002 at the Hill of Tara. The Meath king requested a month-long truce to rally his subordinates to his side, which Boru accepted, however, Máel Sechnaill was quickly abandoned by his northern Uí Néill kinsmen. Having failed to raise enough troops to challenge Boru, he was forced to abdicate, thus ending the hereditary right of the Uí Néill to the title of High King. Although they remained Kings of Meath, the power and prestige of the southern Uí Néill would never recover.[40]

Monastic settlement

editTraditional accounts of the arrival of Saint Patrick and Christianity to Ireland are centred on Meath and its legendary High Kings. Folklore states that he travelled to the kingdom to light a Paschal Fire on the Hill of Slane, in defiance of High-King Lóegaire mac Néill, who was on the nearby Hill of Tara celebrating a pagan festival. Patrick was then summoned to the king's court and so impressed Lóegaire with his teachings that he was allowed to continue preaching Christianity across Ireland. While Christian missionaries were documented in Ireland long before the time of Saint Patrick, and accounts of his activities are heavily shrouded in myth, what is known is that by the late 6th century AD Christianity had supplanted Celtic Paganism in every corner of the island.[41] In a similar manner to how the Celts assimilated prehistoric traditions into their beliefs, many Celtic pagan beliefs and festivities were adapted to Celtic Christianity, such as Samhain, which became Halloween, and Imbolc, which became St. Brigid's Day.

By the 7th century a network of monasteries and religious settlements had been set up throughout Ireland and Western Scotland, supported by local kings and chieftains. Beginning at this time, the "Golden Age of Irish Christianity" lasted for several centuries. Irish Scholars preserved invaluable Latin texts and Gaelic monasteries developed into centres of learning which attracted theologians from across Europe. These monasteries sent missionaries to northern and central Europe to re-ignite Christianity and Latin tradition in areas where it had lapsed following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. One of Ireland's national nicknames, "the land of saints and scholars", is in reference to this period.

Patronage of the Church was also used as a political tool to project wealth and prestige in Irish kingdoms until the 16th century. Successive High Kings and Kings of Meath supported the establishment of prominent religious settlements and institutions, such as Kells and Clonard Abbey, the latter of which taught Ireland's most significant saints, dubbed the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. During the golden age, the monasteries of Meath were associated with several of Ireland's most famous artefacts, which are considered to be among the finest examples of Insular and medieval Christian art in existence.[42]

-

Tara Brooch,

c. 7th century -

Donore Handle,

c. 8th century -

Book of Kells,

c. 9th century -

Kells Crozier,

c. 10th century -

St. Patrick's Shrine,

c. 11th century

As knowledge of the importance and wealth of the Irish monasteries became more widely known, they began to attract the attention of Vikings, who were raiding throughout Britain and Ireland in the 8th century. The most distinctive feature of Irish monasteries, their round towers, were built in response to these Viking raids. Eventually, the Vikings established kingdoms and founded Ireland's first cities along coastal areas, including in neighbouring Dublin. The High Kings and lesser kingdoms waged near-continuous war with these Norse-Gael settlers for over two centuries.

Lordship of Ireland (1169–1542)

editNorman period

editIn 1166, Diarmait Mac Murchada was banished from Ireland by the High King Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair for the abduction of Lady of Meath Derbforgaill ingen Maeleachlainn, wife of Tigernán Ua Ruairc, King of Breifne. Mac Murchada returned with Norman allies and landed at Bannow in Wexford in 1169, after which they conquered northward throughout 1169–70, initiating the Norman Invasion of Ireland. In response, the High King assembled an alliance which included King Magnus Ua Máel Sechlainn of Meath as well as soldiers from Connacht, Breifne and Dublin along with their respective kings. They confronted Mac Murchada's forces at Ferns and an agreement was reached whereby Mac Murchada was acknowledged as king of Leinster, in return for acknowledging Ruaidrí as his overlord and agreeing to send his foreign allies away permanently.[43] However, Mac Murchada breached the agreement and enlisted more Normans to his side before continuing his conquests, capturing Dublin in 1171 and forcing the capitulation of Magnus Ua Máel Sechlainn.

Following Mac Murchada's death in May 1171, Strongbow succeeded him as King of Leinster and, once again, Magnus joined the High-King's coalition army to oust the Normans, however, their forces were routed during an unsuccessful siege of Dublin. Fearing that Strongbow was growing too powerful and might set up his own independent kingdom in Ireland, Henry II of England landed in Ireland in October 1171 to establish control over both the Irish and the Normans. Henry's campaign in Ireland was largely successful and he managed to reign in the Normans as well as a few Irish kingdoms which also submitted to him. Most crucially, he retained the city of Dublin, and Baron Hugh de Lacy was made its bailiff.[44] Henry's appointment of de Lacy was intended to act as a counterbalance to Strongbow. However, in order to achieve this, de Lacy would need a strong holding on Irish soil and it was decided that the Kingdom of Meath was to be granted to de Lacy.

This grant posed an issue for Henry as the previous decade had been a tumultuous time in Meath. There were four rival heirs to the kingship and each claimant held a different part of the kingdom. The strongest claim came from the King of Breifne, Tigernán Ua Ruairc, who – through conquest, marriage and an alliance with the church – had subsumed almost all of eastern Meath into his kingdom by the time of the Norman arrival.[45] Strongbow also had nominal claim to Meath as King of Leinster. A war of succession within the Clann Cholmáin dynasty meant that both Magnus and Art Ua Máel Sechlainn were also vying for the kingship of Meath. To circumvent this problem, Henry defined the borders of Meath as they had been in 1153 and ignored all subsequent subdivisions. In March 1172 he granted control of Meath to de Lacy on the condition that de Lacy could personally retain the kingdom with near total autonomy if he could conquer it.

Shortly after Henry left Ireland, Hugh de Lacy invaded Meath, setting up countless motte and bailey fortifications throughout the kingdom. de Lacy made the ecclesiastic centre of Trim his stronghold, constructing a huge ringwork castle defended by a stout double palisade and external ditch on top of the hill. With de Lacy now at the border of Ua Ruairc's outermost settlement of Kells, a parlay was arranged and the two leaders met on the Hill of Ward for negotiations. During these negotiations, a dispute erupted and de Lacy's men killed Ua Ruairc. Both sides blamed the other, with the Irish annals reporting that Ua Ruairc was "treacherously slain".[46]

By 1175, de Lacy had conquered the entire territory, executing Magnus Ua Máel Sechlainn that year. He expanded existing settlements into charter towns throughout Meath, including Trim, Athboy, Kells and Navan; and he married Rose Ní Conchobair, the High-King's daughter, in order to cement his claim as Lord of Meath.

Hugh de Lacy died in 1186 and several informal divisions and feuds among de Lacy's descendants over control of the lordship followed over the next century. The Lordship was formally shired in 1297 into the County of Meath.[47] Following this, Meath developed into the largest and wealthiest shire in Ireland, with the eastern portion characterized by well-populated market towns, nucleated villages and a strong commercial focus on labour-intensive cereal cultivation, with one English official noting that Meath was "as well inhabited as any shire in England".[48] Many of the Lordship of Ireland's judges, barristers and government officials such as Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, Chief Baron of the Irish Exchequer and Chief Justice of the Common Pleas for Ireland hailed from the county.

Between the 13th and 15th centuries, English power diminished significantly in Ireland for three primary reasons. Firstly, there was a reconsolidation and resurgence in the power of the Irish kingdoms which had been shattered during the Norman invasion. Secondly, the onset of the Black Death devastated nucleated settlements such as walled Anglo-Norman towns but had a significantly smaller impact in more sparsely populated Gaelic kingdoms. Lastly, and of most concern to the English crown, the gradual gaelicisation of the Normans meant that many of the most prominent Anglo-Norman families, who were meant to act as England's viceroys in Ireland, no longer followed English laws or customs.[49]

English authority continued to retreat eastward until Trim, Athboy and Kells were the outermost settlements of The Pale, an area centred around Dublin where English law was still obeyed. This situation meant that by the 1500s part of County Meath was within the Pale while other areas – which were inhabited by both the Gaelic Irish as well as Normans who were once loyal to the Crown – were now outside the control of the authorities in Dublin.[50]

Kingdom of Ireland (1542–1800)

editTudor conquest

editThe papal bull Laudabiliter of Pope Adrian IV, issued in 1155, recognised the Angevin monarch as Dominus Hibernae (Latin for "Lord of Ireland"). When Pope Clement VII excommunicated Henry VIII in 1533, the constitutional position of the lordship in Ireland became uncertain. Following Henry's split with the church, the Tudors heralded the end of monastic Meath. Church Lands which comprised roughly one-third of the county were seized and granted to Protestant English statesmen and soldiers as a form of payment. Monasteries were suppressed and their treasures were either looted or scattered by Irish scholars to protect them. [49] Meath was invaded by Tyrone and its allies in 1539 who raided as far south as Navan, which was razed to the ground. King Conn O'Neill had been recognized as "King of our realm in Ireland" by Pope Paul III and was encouraged to expel Protestant influence from the island.[51] However, the conflict stoked an unexpectedly swift reaction from the typically lethargic Dublin government, and Tyrone was defeated by Lord Deputy Grey and forced to sue for peace in 1541.

Henry had broken away from the Holy See and declared himself the head of the Church in England, and subsequently refused to recognise the Roman Catholic Church's vestigial sovereignty over Ireland. For this reason, and also to address England's waning power in Ireland, Henry proclaimed the Kingdom of Ireland in 1542, with himself as its monarch. The following year, the Counties of Meath and Westmeath Act was passed by the Parliament of Ireland and Meath was officially divided in two. The act was intended to allow a more effective administration in both counties, particularly in Westmeath, which England had lost control of. A new shire town at Mullingar was established along with four new baronies, while Trim retained its status as the shire town of Meath.[52]

Despite the general loyalty of the "Old English" of Meath to the government in Dublin, the introduction of new Anglican English settlers, seen as more reliable by the English government, undermined the power of the Anglo-Norman aristocracy who had remained overwhelmingly Catholic following the Reformation. Although there was a fervent anti-Catholic sentiment in England at this time, no punitive laws were enacted out of fear that they would provoke further rebellion. However, this changed following England's victory over the Irish kingdoms in the Nine Years' War in 1603. With Ireland subdued, the English pursued a series of Penal Laws restricting the rights of Catholics, which were accelerated following the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

Protestant Ascendancy

editThe uneasy peace that had persisted between Catholics and Protestants for several decades unravelled when the anti-Catholic Long Parliament gained traction in England in 1640. Fearing further persecution, the dispossessed Irish of Ulster went into rebellion in 1641 to regain the lands they had lost to the plantations.[53] Exaggerated news of brutal Catholic massacres against Protestants spurred the English into aggressive action, and the peaceful lands of Meath were indiscriminately ransacked by puritanical armies in retribution. In response, the lords of Meath met at Trim and issued their remonstrance to King Charles I. Sir John Read was sent to deliver it; however, gripped by anti-Catholic hysteria, officials in Dublin seized Read and tortured him, questioning whether the King and his Catholic wife Henrietta were in league with the Irish rebels.

As the rebellion intensified, the Ulstermen once again conquered southward into Meath, crushing an English garrison at the Battle of Julianstown. A contingent of Old English lords led by Viscount Gormanston rode out to halt their advance. A parlay was arranged at the Hill of Crufty and the Irish, led by O'Moore and O'Reilly, met with the Anglo-Norman gentry of Meath. Seeing that they fought for a common cause, the leaders of the two sides embraced amid the acclamation of their followers, and the lords of Meath rode home to rally their forces against the English.[54]

On 22 March 1642 the Catholic hierarchy held a synod at Kells and almost unanimously agreed that the rebellion was a just war. They drafted a Confederate Oath of Association in May and Meath lawyer Nicholas Plunkett encouraged Catholic nobles to take up the oath. After the outbreak of the English Civil War, an assembly was held in Kilkenny and the provisional government of Confederate Ireland was established, which took up arms with the Royalists against the Parliamentarians. The Royalists were crushed by Oliver Cromwell, who then set about ending the Irish Confederate Wars by engaging in an unquestionably brutal conquest of Ireland, resulting in the death of up to 40% of the island's population.[55]

Following the conquest, further Penal Laws were enacted and Catholics were forbidden to hold government office and stripped of their lands under the Down Survey. Former aristocratic families were forced to send their children abroad for education to Irish seminaries in France and the Spanish Netherlands. The "New English" along with those who had converted to Anglicanism occupied the Parliament, becoming what would later be termed the Protestant Ascendancy. This period also saw an influx of Huguenots into Meath, and surnames such as Beaufort and Metge appeared in the county for the first time.

Some Old English families were able to recover their lands and return to Meath following the restoration of King James II. Although James did little to improve the overall situation of Irish Catholics, he was backed by them during the Glorious Revolution, while Protestants overwhelmingly backed William of Orange during the Williamite War in Ireland. The defeat of the Jacobites at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690 forced James to flee to France, ending the prospect of an autonomous Irish kingdom. This battle is seen as a seminal event in Irish history and is still celebrated every year by Ulster Unionists.

Towards the end of the 18th century the Penal Laws were relaxed and Catholic merchant families such as Fay and Connolly were granted trading privileges in Trim and Navan. Celebrated Meath sculptor Edward Smyth was commissioned by Catholics in Navan to produce a crucifix for the town's new chapel in 1792, which is still located in the church to this day.[31] As sectarian tensions eased, liberal ideas began to spread among members of the Protestant Ascendancy, such as Wolfe Tone and Henry Grattan, and many came to see themselves as citizens of an Irish nation and championed Catholic emancipation. Ireland briefly secured parliamentary independence through the Constitution of 1782 which ushered in Ireland's first economic boom in centuries, as trade flourished and the population grew exponentially. However, these freedoms were abruptly ended with the Act of Union 1800, when Ireland was subsumed into the United Kingdom.

19th century

editThe economic boom of the late 18th century came to a sudden and catastrophic halt following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. During the war, Ireland had become known as the "Food larder of Europe", and the tenant farmers and landlords of Meath relied heavily on tillage, which fetched an artificially high price due to a surge in wartime demand. Further, a substantial number of Irish soldiers who comprised as much as 25% of the entire British Army and Navy during the war were now made redundant. As post-war trade between Britain and Europe recovered, demand for Irish tillage collapsed; however, rents remained the same and the population continued to boom. As economic stagnation set in, the once well-managed, prosperous estates of Meath gave way to mismanagement and absenteeism, and the tenant farmers were pushed further into poverty.[56][57]

This dire economic state resulted in a surge of Irish nationalism and demands to repeal the disastrous Act of Union. Nationalist sentiment was widespread in Meath, as reflected in the Meath Parliamentary constituency, which returned several of 19th century Ireland's most prominent nationalist politicians, including Daniel O'Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell and Michael Davitt. Owing to its symbolic place in the national psyche, Daniel O'Connell held a rally on the Hill of Tara in August 1843 which was attended by between 500,000 and 1 million people, making it one of the largest crowd gatherings in Irish history.[58]

To address rising poverty and growing unrest in Ireland, the British government set up workhouses in the 1830s and began constructing railroads. However, these efforts were largely unsuccessful and the impoverished of Meath, pushed to the brink by high rents and mass unemployment, were wiped out by the Great Famine of 1845–49. Having reached over 183,000 in 1841, the population of Meath would fall to 67,000 by 1900. The famine had a lasting cultural, societal and linguistic effect on the county. Pre-famine census records show that Meath had been a region with an "undoubted Irish speaking majority",[59] but by the late 1800s the Irish language was virtually extinct within the county. The famine-era workhouse and mass grave at Dunshaughlin is today a memorial to its victims.

The famine shed light on the detrimental effects that Ireland's land laws were having on the economic and social well-being of the country, and the British government's lacklustre response to the crisis further strengthened the cause of Irish nationalists. The Protestant Ascendancy went into steep decline following the famine and many landholders were effectively bankrupt, leading to the ad hoc sale of lands to unproductive use. The push for reform escalated in the 1870s into a period of sporadic violence and civil unrest known as the Land Wars.

Thomas Brennan, of Yellow Furze, co-founded the Irish National Land League in 1879 alongside Michael Davitt. His staunch republicanism and socialist leanings put him at odds with the League's executive, and he was excluded from the Irish National League set up by Parnell in 1882. Brennan moved to the United States and raised money for the republican cause, advocating total Irish independence as opposed to Home Rule to the Irish-American diaspora.[60] This revealed an ideological divide within the nationalist movement, between those who favoured greater legislative independence under the British crown, as had been achieved in the 1780s, and those who advocated for completely severing ties with the United Kingdom.

Some of the political reforms desired by the nationalists were finally realised under the Local Government Act of 1898. The act set up urban and rural districts as well as county councils to take over local government from landlords. Under the reforms, small sub-councils and boroughs were abolished and Meath County Council was granted full control over the jurisdiction. The council sat at Navan, which became the new county town of Meath, ending Trim's 600-year status as Meath's shire town.[61][62]

20th century

editThe reforms proposed by the UK government failed to stem the rising tide of nationalism, which spilled over into the 20th century as the 1916 Easter Rising. The Battle of Ashbourne was one of the few skirmishes which took place outside of Dublin during the rising and was its sole success. On 28 April 1916, members of the Dublin Volunteers Fifth (Fingal) battalion, led by Thomas Ashe, surrounded a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) police station in Ashbourne and demanded their surrender. RIC reinforcements were dispatched from Navan and upon arriving at the scene a firefight ensued during which 8 RIC members were killed and 15 wounded, forcing them to retreat. On the orders of Patrick Pearse, Ashe and his battalion surrendered the following day.[63]

Meath's Eamonn Duggan served as the IRA's director of intelligence during and after the rising and was a signatory of the Anglo-Irish treaty in 1921. Meath largely sided with the pro-treaty forces during the Civil War, with the Louth–Meath constituency returning one anti-treaty and four pro-treaty TDs in the 1922 general election. Duggan later joined Cumann na nGaedheal and held various ministerial offices until his death in 1936. Following independence, various government-backed Gaelic revival efforts were centred on the county and its history, including the foundation of 5 Gaeltacht areas within Meath, and the symbolic hosting of the Tailteann Games.

The declining population of Meath gradually stabilised as emigration balanced with high natural birth rates. Outward migration from the county remained substantial until the reforms of Seán Lemass in the 1960s strengthened industry by injecting capital into the economy and abandoning the policy of autarky.[64] These reforms, coupled with EEC membership in 1973, brought jobs and investment into the county, and the extraction and textile industries prospered. By the 1971 census, Meath's population had surpassed 70,000 for the first time in eighty years. Despite a severe recession in the 1980s, the growth of Meath's economy and population became exponential in the late 1990s and early 2000s during the Celtic Tiger era.

As places such as Trim, Navan and Kells developed into major commuter towns of Dublin, the county grew increasingly reliant on the overheated construction sector, leaving Meath hard-hit by the property collapse in 2008. From 2014 onward, the economy experienced a robust recovery, and by 2016 Meath had the third lowest unemployment rate in Ireland.[65] Meath surpassed its pre-famine population in 2011, becoming one of only five counties in the State to do so.

Places of interest

editAs a consequence of its location in the centre of Ireland, Meath has an abundance of historic sites.

All periods of Irish history are represented in the landmarks of the county, spanning from the prehistoric tombs at Brú na Bóinne, the early Christian monasteries at Kells and Bective, the Norman-era fortifications at Trim and Dunmoe, the manor houses and estates of the 17th and 18th centuries such as those at Bellinter and Slane, the famine-era workhouse and graveyard at Dunshaughlin, all the way up to the Battle of Ashbourne historic site, which commemorates the sole victory of the Irish Volunteers during the 1916 Easter Rising.

In terms of natural attractions, the county has a relatively tame landscape compared to other parts of Ireland, with no mountains, a short coastline and generally little forest cover. There are however a number of National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) protected sites within the county. The River Nanny Estuary & Shore and the River Boyne & River Blackwater are listed as Special Protection Areas.

Additionally, all bogs within the county; those being Mount Hevey, Girley, Killyconny, Molerick and Jamestown are listed as either Special Areas of Conservation or Natural Heritage Areas. Lough Bane, Lough Glass, White Lough, Ben Loughs and Lough Doo are all also protected by the NPWS.

Landmarks

edit- Athcarne Castle

- Athlumney Castle

- Ballinlough Castle

- Battle of the Boyne Visitor Centre

- Bective Abbey

- Bellinter House

- Boyne Hill Estate

- Clonard Abbey

- Dangan Castle

- Dardistown Castle

- Donaghmore Round Tower

- Dowth

- Dunsany Castle and Demesne

- Dunmoe Castle

- Dunshaughlin Famine Workhouse

- Fairyhouse Racecourse

- Fourknocks Passage Tomb

- Gormanston Castle

- Hill of Slane

- Hill of Tara

- Hill of Ward

- Irish Military War Museum

- Kells Abbey

- Killeen Castle

- Knowth

- Loughcrew

- Newgrange

- Oldcastle World War I POW Camp

- Robertstown Castle

- St. Mary's Abbey

- Skryne Castle

- Skryne Monastic Site

- Slane Castle

- Spire of Lloyd

- Tailteann

- Tattersalls Country House

- Trim Castle

- Trim Cathedral

Natural attractions

edit- Balrath Woods

- Bettystown Beach

- Boyne Valley

- Girley Bog

- Grove Gardens

- Jamestown Bog

- Killyconny Bog

- Larchill Arcadian Gardens

- Loughs of the Upper Boyne Valley

- Leinster Blackwater

- Lough Sheelin

- Loughcrew Historic Gardens

- Molerick Bog

- Mount Hevey Bog

- Nanny Estuary

- Rathbeggan Lakes

- Slieve na Calliagh

- Sonairte National Ecology Centre

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1841 | 183,828 | — |

| 1851 | 140,748 | −23.4% |

| 1861 | 110,373 | −21.6% |

| 1871 | 95,558 | −13.4% |

| 1881 | 87,469 | −8.5% |

| 1891 | 76,987 | −12.0% |

| 1901 | 67,497 | −12.3% |

| 1911 | 65,091 | −3.6% |

| 1926 | 62,969 | −3.3% |

| 1936 | 61,405 | −2.5% |

| 1946 | 66,232 | +7.9% |

| 1951 | 66,337 | +0.2% |

| 1956 | 66,762 | +0.6% |

| 1961 | 65,122 | −2.5% |

| 1966 | 67,323 | +3.4% |

| 1971 | 71,729 | +6.5% |

| 1979 | 90,715 | +26.5% |

| 1981 | 95,419 | +5.2% |

| 1986 | 103,881 | +8.9% |

| 1991 | 105,370 | +1.4% |

| 1996 | 109,732 | +4.1% |

| 2002 | 134,005 | +22.1% |

| 2006 | 162,831 | +21.5% |

| 2011 | 184,135 | +13.1% |

| 2016 | 195,044 | +5.9% |

| 2022 | 220,826 | +13.2% |

| [2][66] | ||

Meath had a population of 220,826 according to the 2022 Census; an increase of 25,252 (+13.2 percent) since the 2016 census of Ireland, making it the second fastest growing county in Ireland, after County Longford. Population growth from 2016 to 2022 included a natural increase of 3,558 people (+1.62 percent) since the last census, coupled with an increase of 22,078 people (10.0%) due to net migration into the county. Immigration from people born outside of the Republic of Ireland resulted in a net increase of 10,687 people. Migration of those from other Irish counties, primarily from neighbouring County Dublin, produced a net increase of 11,391 people. Owing to its proximity to Dublin, Meath is the least indigenous county in Ireland, with just 71,356 usual residents (32.4 percent) recorded as being born within the county. Just under half of all Meath residents (49.2 percent) were born elsewhere in the State, and the remaining 18.3 percent were born abroad.[67] The county's population density was 94 people/km2 in 2022, making it one of just 8 counties in Ireland with a population density above the all-island average density of 83.5 people/km2.

In 2022, 6.4 per cent of the county's population was reported as younger than 5 years old, 23.5 per cent were between 5 and 19, 57.8 per cent were between 20 and 65, and 12.3 per cent of the population was older than 65. 5,661 people (2.6 per cent) were over the age of 80. Across all age groups, there was a roughly even split between females (50.2 per cent) and males (49.8 per cent).[68]

In 2021, there were 2,847 births within the county, and the average age of a first time mother was 31.6 years.[69]

Population trends

editThe population of Meath suffered a significant decline between 1841 and 1901, decreasing by almost two-thirds (183,828 to 67,497); it stabilised between 1901 and 1971 (67,497 to 71,729), and there was a substantial increase between 1971 and 1981 to 95,419. This increase was mainly due to a baby boom locally. The population then continued to increase at a constant rate, before increasing at an explosive rate between 1996 and 2002, from 109,732 to 134,005. This is due primarily to economic factors, with the return of residents to live in the county, and also an echo effect of the 1970s baby boom. The census of 2022 gives a figure of 220,296, including a dramatic increase in inward migration to the county. Meath is one of only 5 counties in the state which has a population higher than its 1841 pre-famine peak.

This population growth has seen divergent trends emerge in recent years, with mild depopulation in the north and west of the county more than offset by large increases in the population of the eastern and south-eastern parts of the county, principally owing to inward migration to districts that have good proximity via road to the business parks on the western outskirts of Dublin. The accession of Poland and the Baltic States to the European Union in 2004 resulted in a significant influx of workers from these countries to work in sectors such as agriculture, quarrying, construction and catering.[70]

Migration

editThe five largest foreign national groups in Meath are: Polish (2.2 percent), British (1.9 percent), Romanian (1.6 percent), Lithuanian (1.3 percent), American (0.6 percent), Latvian (0.6 percent), and Nigerian (0.6 percent).

| Country | Poland | United Kingdom | Romania | Lithuania | United States | Latvia | Nigeria | Brazil | India |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizenship (Country only) |

3,933 | 2,756 | 3,170 | 3,030 | 312 | 1,082 | 476 | 834 | 925 |

| Citizenship (Dual Irish-Country) |

903 | 1,042 | 525 | 190 | 1,091 | 183 | 552 | 152 | 57 |

| Combined Population (2022) | 4,836 | 3,798 | 3,695 | 3,220 | 1,403 | 1,265 | 1,028 | 986 | 982 |

Ethnicity

editIn 2022, the racial composition of the county was:[72]

- 89.9% White (78.7% White Irish, 10.7% Other White Background, 0.5% Irish Traveler)

- 2.6% Asian

- 1.8% Black

- 1.9% Others including mixed

- 3.8% Not stated

Religion

editAccording to the 2022 Census, published by the Central Statistics Office, 82.6% of County Meath's residents identify with a religion. 80.0% affiliate with Christianity and its various denominations, and the other 2.6% are adherents of non-Christian religions. The remaining 13.1% have no religion, with 4.3% of people not stating their religion.

The largest denominations by number of adherents in 2022 were the Roman Catholic Church with 159,410; followed Orthodox Christianity with 6,512; the Church of Ireland, England, Anglican and Episcopalian with 4,446; and all other Christian denominations including Presbyterian, Pentecostal, Lutheran and Evangelical with 5,176 adherents. Among the non-Christian denominations, Muslims are by far the largest group, with 3,153 adherents, followed by Hinduism with 881 and Buddhism with 330. Additionally, 9,495 people did not state their religion.[73]

The Cathedral of Saint Patrick in Trim was the seat of the former Diocese of Meath, which is now the Diocese of Meath and Kildare in the Church of Ireland. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Meath has its seat at Mullingar, County Westmeath. A former cathedral was located at Clonard Abbey, however, it was destroyed by fire in 1206. Thomas Deenihan is the current Bishop of Meath. The county's largest Presbyterian church is located in Kells, and the Navan Muslim Community Centre, which is primarily used as a mosque, is located on Kennedy Road in Navan.

Continuing the trend which has been observed throughout Ireland since the Census of 2006, a significant increase in the number of people who identified as having no religion was observed in the 2022 census. This demographic has increased by 260% since 2011, from 7,990 to 28,771. People with no religion now account for 13.1% of the county's population, up from 8.1% in 2016.

Irish language

editMeath contains Leinster's only Gaeltacht areas, at Ráth Chairn, close to Athboy, and Baile Ghib, located northwest of Navan. With a combined area of 44 km2, they are the two smallest Gaeltachts in Ireland. As of 2022, there were 2,093 people living within the Meath Gaeltacht areas, of which 1,179 (56.3 percent) stated that they were Irish speakers.[74]

Unlike the Gaeltachts of the west of Ireland, the Meath Gaeltachts are the result of a government gaelicisation scheme to reintroduce the Irish language to the east of the country. In total, 5 Irish-speaking settlements were set up in Meath between 1935 and 1939 – Ráth Chairn, Baile Ghib, Cill Bhríde, Cluain an Ghaill and Baile Ailin. They were established on fertile land which had been allowed to fall into disrepair by absentee landlords and was consequently repossessed by the Irish Land Commission. In total, 122 Irish-speaking families moved to the county. They were primarily from Connemara, but some families were also from County Kerry.

Over the years Cill Bhríde was subsumed into Ráth Chairn, and Cluain an Ghaill was subsumed into Baile Ghib. The fifth and final Gaeltacht to be set up – Baile Ailin – failed after a generation, as several Irish-speaking families moved away and day-to-day use of the Irish language failed to take hold amongst the children of those who remained. The two surviving settlements were officially recognised as Gaeltacht areas in 1967.[75]

According to the 2022 Census, 39.8 per cent of Meath residents were able to speak Irish, up from 38.6 percent in 2016. Of that, there were 2,594 Gaeilgeoirí (people who speak Irish everyday outside of the education system) in County Meath.[76] In addition, 27,566 people stated that they speak Irish daily within the education system only. The Greater Dublin Area has the highest number of Irish-medium schools in Ireland, and there are seven Gaelscoileanna outside the Gaeltacht areas within Meath.[77]

Urban areas

editNavan is the county town and by far the largest settlement in Meath. It is also the 4th largest town in the state, excluding cities.

Meath is predominantly an urban county, although a large percentage of its residents live in rural areas. According to the 2022 Census, 56 percent of the county lived in urban areas, and the remaining 44 percent lived in rural areas. Just over half of the county's population (52.1 percent) live in the ten largest towns. Historically, the largest towns in Meath were located in the north and west of the county, such as Trim, Navan and Kells. However, in recent years settlements in the south and east of the county such as Ashbourne, Dunboyne, and the coastal agglomeration of Bettystown, Laytown, Mornington and Donacarney have expanded significantly, and the majority of the county's fastest growing towns are now located in these areas.

| Rank | Constituency | Pop. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Navan Ashbourne |

1 | Navan | Meath West | 33,886 | Laytown–Bettystown–Mornington–Donacarney Ratoath | ||||

| 2 | Ashbourne | Meath East | 15,680 | ||||||

| 3 | Laytown–Bettystown–Mornington–Donacarney | Louth | 15,642 | ||||||

| 4 | Ratoath | Meath East | 10,077 | ||||||

| 5 | Trim | Meath West | 9,563 | ||||||

| 6 | Drogheda (Southern Environs) | Louth | 8,145 | ||||||

| 7 | Dunboyne | Meath East | 7,155 | ||||||

| 8 | Dunshaughlin | Meath East | 6,644 | ||||||

| 9 | Kells | Meath West | 6,608 | ||||||

| 10 | Duleek | Meath East | 4,899 | ||||||

Economy

editThe Central Statistics Office estimates that Meath's Total Household Income in 2017 was €5.253 billion, ranking 6th among Irish counties. Meath also ranks 6th in the country by per capita disposable income, at €20,493 or 95.8% of the State average.[79] Meath residents are also the 6th highest per capita tax contributors to the State, returning a total of €1.311 billion in taxes in 2017 – roughly equivalent to the entire Midlands Region. Major industries include services, retail, agriculture and food processing, mining, manufacturing and tourism.

Services, retail and hospitality

editServices, retail and the hospitality industry are the primary employers in the county. Navan was historically a manufacturing town, and involved in the household goods sector. Navan was also a centre in the Irish carpet-making industry, before this was lost to overseas competition.[80]

Tourism benefits from the abundance of historically important pre-historic and early Christian sites, as well as castles and manor houses within the county, many of which are currently in use as hotels. Due to its rich history, Meath is marketed by Fáilte Ireland, the country's national tourism agency, as "Ireland's Heritage Capital". Good local infrastructure means that most of Meath's tourist attractions are located within a one-and-a-half-hour drive from Dublin Airport. Despite this, Meath received just 162,000 overseas tourists in 2017 – placing it 17th out of 26 counties.[81] Tourism is worth in excess of €50 million to the local economy each year.

In addition to historic attractions, Meath is home to scenic lakes, beaches, wooded areas and several European-designated areas of ecological significance. The only permanent amusement park in Ireland is Emerald Park, located in Ashbourne, which has 3 roller coasters, including Cú Chulainn, Ireland's largest roller-coaster.

Meath also has a growing science and biotechnology field. In 2018, Shire, one of the world's largest pharmaceutical companies, opened a €350 million international disease research centre in Dunboyne, which was sold to Merck & Co. in 2020.[82]

Agriculture

editThe agricultural products of the county are beef, pork, dairy, poultry, vegetables and cereals. Meath has a strong farming tradition and up until the 1911 Census the most commonly listed occupation in the county was farm labourer. Meath is ranked 2nd in the country for the production of vegetables and 2nd for the production of rapeseed oil.

As of 2018, Meath has the country's 8th largest cattle herd with 275,301 cows. Dairy production was the largest and most profitable agricultural sector in the county and 63.7% of all cattle were dairy cows. The remaining 36.3% were beef cattle. The county also has Ireland's 9th largest sheep herd (150,571 sheep) and 14th largest pig herd (40,259).[83] Meat processors such as Kepak and Dawn Meats are large employers within the county.

There are 4,620 farms in the county, with a total farmed area of 194,886 ha (481,574 acres), accounting for 83% of land area. Of this, 31,201 ha (77,099 acres) was under tillage, the 3rd highest in the country. Although Irish agriculture is heavily dominated by pasture farming, Meath's favourable climate and easterly location give it a much greater capacity than most counties for agricultural diversification, reflected in its robust tillage and vegetable production sectors. The average size of a farm in the county is 42 ha (104 acres), well above the national average of 31 ha (77 acres).

Agriculture supports thousands of jobs within the county and, according to the Irish Farmers' Association, the total value of agricultural produce from Meath in 2018 was €541 million, ranking it 6th in Ireland.[84]

Extraction and energy

editDue to the geology of the area, Meath has enormous reserves of Lead and Zinc, which are extracted at Tara Mine in Navan. Tara is both Europe's largest and deepest mine and is currently owned by Boliden AB. The mine commenced operations in 1977, and a total of 85 million tonnes of ore has been extracted from it, producing an average of 2.6 million tonnes of zinc ore annually.[85]

Glacial deposits of gravel exist in a band stretching from the Offaly border at Edenderry, to the sea at Laytown. This is the basis of a long quarrying tradition. The local availability of large deposits of limestone and shale also gave rise to a significant cement production industry within the county. The two largest cement facilities are at Kinnegad and Platin, the latter of which is owned by Irish Cement and has the capacity to produce 2.8 million tonnes of cement per annum, which is primarily transported via rail to Dublin for use or export.

Ireland's first waste-to-energy plant opened in Duleek in 2011 and produces 17 MW of electricity per annum. SSE Airtricity aim to build a 208 MW gas-fired power plant south of Drogheda. Meath has a small but growing biomass industry, however other forms of renewable energy such as wind power and hydroelectricity have stalled due to widespread objections. There is an abundance of natural subterranean faults where water from hot springs, such as those Enfield, rise to the surface at 25 °C. There is potential for these to be used for Shallow Geothermal Energy generation.[86]

Infrastructure

editRoad

editThe county is served by four motorway routes. The M3 connects Navan to Dublin and runs from just south of Kells to Clonee, a distance of 48 km (30 mi). The M4 passes through the south of the county and serves as the main road to both Sligo and Galway, when it divides at Kinnegad into the N4 and the M6. The M1 Dublin to Belfast route traverses East Meath for 17 km (11 mi) before bypassing Drogheda.

A 13 km (8.1 mi) stretch of the N2 from Ashbourne to the Dublin border at Ward Cross was upgraded to the M2 motorway in 2009. Two national primary routes pass through the county, The N3 and the N2. The M3 becomes the N3 south of Kells before continuing on to County Cavan, a distance of 12 km (7.5 mi). The N2 begins at Ashbourne and crosses the county for roughly 30 km (19 mi) before entering County Louth near Collon. Two national secondary routes pass through the county. The majority of the N51 Drogheda to Mullingar route is located within Meath, and crosses the county for 40 km (25 mi), passing through Slane, Navan and Athboy.[87]

The N52 which stretches from Nenagh, where it joins the M7, to Dundalk, where it joins the N1, crosses the county for 36 km (22 mi) and passes through Kells. Bus Éireann, as well as private coach operators, provide bus services to villages and towns across the county. Areas close to Dublin city in southern and eastern Meath such as Clonee and Dunboyne are also served by Dublin Bus.

Rail

editIrish Rail provides frequent rail services from Dunboyne and M3 Parkway to Dublin city centre. Laytown railway station and Gormanston railway station have a commuter rail service and are located along Dublin's Northern Commuter Line which runs from Dundalk to Dublin. A commuter train service (Western Commuter Line) passes through Enfield, although the service is less frequent as the station is primarily used for the long-distance Irish rail routes to Longford and Sligo.

Navan is currently served by a freight-only spur railway line from Drogheda on the Dublin-Belfast main line, for freight traffic (zinc and lead concentrate from Tara Mines in Navan to Dublin Port) connecting at Drogheda. Currently, the only commuter rail from Dublin to Navan must also pass through Drogheda. The direct Dublin–Navan railway line remains disused, though still intact. In June 2018, the Department of Transport stated that it would review reopening the line by extending the link past the M3 parkway in 2021.[88]

Air

editFor commercial and international flights, Meath is serviced by Dublin Airport, which is the closest international airport to the county and has good road links with most major towns. For light aircraft and recreational flying, there are several airstrips located throughout the county which serve as the base of operations for local flying clubs.

The Trim Aerodrome is primarily used for microlight flying. The Ballybog Airstrip opened in 1990 and provides a number of recreational aviation activities such as hot air balloon rides and air shows. There are also airfields at Navan and at Moyglare, across the river rye from Kilcock, County Kildare.

There is also a military landing strip at Gormanstown Camp which is not actively used for aircraft. However, the Irish Defence Forces continue to utilise the airstrip for ground-to-air combat training.

Sport

editGAA

editGaelic football is the most popular sport in the county, and the Meath county football team competes annually in Division 2 of the National Football League, the provincial Leinster Senior Football Championship and the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship. Meath has long been the second power of Leinster football, behind rivals Dublin, and 26 Leinster Senior Football Championship Finals have been contested between the two, of which Meath emerged victorious on 9 occasions. In total, Meath has won 21 Leinster titles, making the county the second most successful in the province after Dublin. Given the pre-eminence of Dublin in recent years, Meath's rivalry with Louth is now often regarded as the most heated contest, especially after Meath's highly controversial win over Louth in the 2010 Leinster Final.

Meath has won the national football league 7 times, between 1933 and 1994, the fifth most titles in Ireland. Additionally, Meath has won the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship, the most prestigious competition in Gaelic football, on 7 occasions between 1949 and 1999, also making it the fifth most successful county in Ireland. Meath has also won Leinster's O'Byrne Cup on 10 occasions, the joint-second most after Kildare.

Within the county, Gaelic football clubs compete annually in the Meath Senior Football Championship. The first championship was played in 1887, in which Dowdstown beat Kells by 1 goal to nothing. The most successful club in Meath is Navan O'Mahonys with 20 Senior Football Championship titles. The most successful club at the provincial level is Walterstown, which has won 2 Leinster Senior Club Football Championship titles in 1980 and 1983. No team from Meath has ever won the All-Ireland Senior Club Football Championship.

In Hurling, the Meath county hurling team competes in Division 2 of the National Hurling League, as well as in the Leinster Senior Hurling Championship and the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship. Meath is not a dual county, and has never won a provincial or national hurling title.

As with football, the Meath Senior Hurling Championship is held every year. The first championship in 1902 was won by the Navan Hibernians. The most successful hurling club in the county is Kilmessan, with 29 titles, followed by Trim, with 28. No club team from Meath has ever won the Leinster Senior Club Hurling Championship, and has therefore never qualified for the All-Ireland Senior Club Hurling Championship.

Equestrian activities

editHorse racing, horse breeding and horse training are popular in Meath. There are 54 studs within the county, including the Dollanstown Stud and Estate, which is one of the most expensive private properties in Ireland. Race courses within the county include Navan, Fairyhouse and Bellewstown, which host both National Hunt and Flat horse races, such as the Brownstown Stakes, the Bobbyjo Chase, the Lismullen Hurdle and the Irish Grand National. The latter has been held at Fairyhouse since 1870. Beach horse racing also takes place at the Laytown Racecourse.

The Tattersalls Country House and equestrian grounds, which hosts the International Horse Trials and Country Fair each year, is located opposite the Fairyhouse Racecourse near Ratoath.

Artist Letitia Marion Hamilton from Dunboyne won an Olympic bronze medal for oils and watercolours in the 1948 Summer Olympics for her depiction of The Meath Hunt Point-to-Point Races.

Other sports

editAs with much of the rest of Ireland, association football is a popular spectator sport within Meath. The two most prominent football clubs in the county are Parkvilla F.C. and Dunboyne A.F.C., which both compete in the Leinster Senior League. The lower-tier Meath and District League comprises clubs from counties Meath, Louth, Cavan and Monaghan. Despite being one of the most populous counties in Ireland, it took until 2018 for Dunboyne's Darragh Lenihan to become the first player from Meath to have represented the Republic of Ireland national football team. Since then, Jamie McGrath of Athboy and Evan Ferguson of Bettystown have represented the side.

Golf is also widely played, and there are numerous golf and links courses in Meath. Killeen Castle in Dunsany has an 18-hole championship golf course which was designed by Jack Nicklaus in 2009, and was the venue for the 2011 Solheim Cup. Knightsbrook Golf Club in Trim also has a championship golf course which was designed by Christy O'Connor in 2006. The County Meath Golf Club in Trim and Royal Tara Golf Club near Navan are two of the most popular golfing locations in the county. Links golf is also played adjacent to the Irish sea coast at the Laytown & Bettystown Golf Club.

Athletics within the county is organised by the Meath Athletics Board, which oversees the county's 18 athletics clubs. The board is based in Claremont Stadium in Navan, which is a 400m Tartan Athletics Track and Field Stadium. Sara Treacy of Dunboyne AC represented Ireland in the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

Several teams from Meath compete in the Leinster League in Rugby union, most notably Ashbourne RFC, Athboy RFC, Navan R.F.C. and North Meath RFC. Former Leinster and Ireland wing Shane Horgan, from Bellewstown, played for Boyne RFC in Drogheda at youth level.

Notable people

edit

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Census 2022 – Summary Results – FY003A- Population". 30 May 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Census of Population 2022 – Preliminary Results". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). 23 June 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ Tully, James (19 October 1976). "Local Government Provisional Order Confirmation Act, 1976". Office of the Irish Attorney General. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ Corry, Eoghan (2005). The GAA Book of Lists. Hodder Headline Ireland. pp. 186–191. ISBN 0-340-89695-7.

- ^ "Irish Coastal Habitats: A Study of Impacts on Designated Conservation Areas" (PDF). heritagecouncil.ie. Heritage Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Protected Sites in Ireland". NPWS. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "National Forestry Inventory, Second Cycle 2012". DAFM. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "National Forestry Inventory, Third Cycle 2017". DAFM. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Met Eireann, Historical Data". Met Eireann. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "The Extreme Cold Spell of November–December 2010" (PDF). Met Eireann. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Geology of County Meath" (PDF). geoschol.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "A comparison between clumped C-O and fluid inclusion temperatures for carbonates associated with Irish-type Zn-Pb orebodies" (PDF). Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Ashton, John; Blakeman, Rob. (2016). "The Giant Navan carbonate-hosted Zn–Pb deposit: exploration and geology: 1970–2015". Applied Earth Science IMM Transactions Section B. 125 (2): 75–76. Bibcode:2016AdEaS.125...75A. doi:10.1080/03717453.2016.1166607. S2CID 131635951.

- ^ "Soils of County Meath" (PDF). Teagasc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "North Midlands Area – Slieve Na Calliagh Hill". MountainViews. Ordnance Survey Ireland. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Placenames Database of Ireland – Baronies.

- ^ County of Meath Local Electoral Areas and Municipal Districts Order 2018 (S.I. No. 628 of 2018). Signed on 19 December 2018. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book.

- ^ County of Meath Local Electoral Areas and Municipal Districts (Amendment) Order 2019 (S.I. No. 8 of 2019). Signed on 17 January 2019. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book.

- ^ "Elections 2024: Meath County Council round-up". RTÉ. 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Local Government Act 1991 (Regional Assemblies) (Establishment) Order 2014 (S.I. No. 573 of 2014). Signed on 16 December 2014. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 25 August 2022.

- ^ "1926 Census: Table 9: Population, Area and Valuation of urban and rural districts and of all towns with a population of 1,500 inhabitants or over, showing particulars of town and village population and of the number of persons per 100 acres" (PDF). Central Statistics Office. p. 22. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ Local Government Act 1925, s. 3: Abolition of rural district councils (No. 5 of 1925, s. 3). Enacted on 26 March 1925. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 22 December 2021.

- ^ Local Government Act 2001, 6th Sch.: Local Government Areas (Towns) (No. 37 of 2001, 6th Sch.). Enacted on 21 July 2001. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 21 May 2022.

- ^ Local Government Reform Act 2014, s. 24: Dissolution of town councils and transfer date (No. 1 of 2014, s. 24). Enacted on 27 January 2014. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 21 May 2022.

- ^ Electoral (Amendment) (Dáil Constituencies) Act 2017, Schedule (No. 39 of 2017, Schedule). Enacted on 23 December 2017. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Historic Election Results Database". electionsireland.org. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Meath County Council. "Meath – a rich and royal land". Archived from the original on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ countymeath.com. "County Meath – Newgrange, Slane Castle and the Book of Kells". Archived from the original on 9 March 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ Rowan Kelleher, Suzanne (2004). Frommer's Ireland from $80 a Day (20th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: Wiley Publishing, Inc. p. 204. ISBN 0-7645-4217-6.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Brú na Bóinne – Archaeological Ensemble of the Bend of the Boyne". whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ a b "History of Meath". Navan Historical Society. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Carrowkeel Cairn G Archived 1 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The Megalithic Portal.

- ^ "The Winter Solstice Illumination of Newgrange". Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.