The grass snake (Natrix natrix), sometimes called the ringed snake or water snake, is a Eurasian semi-aquatic non-venomous colubrid snake. It is often found near water and feeds almost exclusively on amphibians.

| Grass snake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Genus: | Natrix |

| Species: | N. natrix

|

| Binomial name | |

| Natrix natrix | |

| |

| Natrix natrix range map | |

| Synonyms | |

Subspecies

editMany subspecies are recognized, including:[2]

- Natrix natrix algirus (fide Sochurek, 1979)

- Natrix natrix astreptophora (Seoane, 1885)

- Natrix natrix calabra Vanni & Lanza, 1983

- Natrix natrix cypriaca (Hecht, 1930)

- Natrix natrix fusca Cattaneo, 1990

- Natrix natrix gotlandica Nilson & Andrén, 1981

- Natrix natrix natrix (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Natrix natrix persa (Pallas, 1814)

- Natrix natrix schweizeri L. Müller 1932

- Natrix natrix scutata (Pallas, 1771)

Natrix natrix helvetica (Lacépède, 1789) was formerly treated as a subspecies, but following genetic analysis it was recognised in August 2017 as a separate species, Natrix helvetica, the barred grass snake. Four other subspecies were transferred from N. natrix to N. helvetica, becoming N. helvetica cettii, N. helvetica corsa, N. helvetica lanzai and N. helvetica sicula.[3]

Description

editThe grass snake is typically dark green or brown in colour with a characteristic yellow or whitish collar behind the head, which explains the alternative name ringed snake. The colour may also range from grey to black, with darker colours being more prevalent in colder regions, presumably owing to the thermal benefits of being dark in colour. The underside is whitish with irregular blocks of black, which are useful in recognizing individuals. It can grow to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) or more in length.[4][5]

Distribution

editThe grass snake is widely distributed in mainland Europe, ranging from mid Scandinavia to southern Italy. It is also found in the Middle East and northwestern Africa.

Grass snakes in Britain were thought to belong to the subspecies N. n. helvetica but have been reclassified as the barred grass snake Natrix helvetica. Any records of N. natrix in Britain are now considered to have originated from imported specimens.[3]

Ecology

editFeeding

editGrass snakes mainly prey on amphibians, especially the common toad and the common frog, although they may also occasionally eat ants and larvae. Captive snakes have been observed taking earthworms offered by hand, but dead prey items are never taken. The snake will search actively for prey, often on the edges of the water, using sight and sense of smell (using Jacobson's organ). They consume prey live without using constriction.[6]

-

Eating an eastern tree frog

-

Eating a common toad

-

Eating European perch

Habitat

editGrass snakes are strong swimmers and may be found close to fresh water, although there is evidence individual snakes often do not need bodies of water throughout the entire season.[6]

The preferred habitat appears to be open woodland and "edge" habitat, such as field margins and woodland borders, as these may offer adequate refuge while still affording ample opportunity for thermoregulation through basking. Pond edges are also favoured and the relatively high chance of observing this secretive species in such areas may account for their perceived association with ponds and water.

Grass snakes, like most reptiles, are at the mercy of the thermal environment and need to overwinter in areas which are not subject to freezing. Thus, they typically spend the winter underground where the temperature is relatively stable.[6]

Reproduction

editAs spring approaches, the males emerge first and spend much of the day basking in an effort to raise body temperature and thereby metabolism. This may be a tactic to maximise sperm production, as the males mate with the females as soon as they emerge up to two weeks later in April, or earlier if environmental temperatures are favourable. The leathery-skinned eggs are laid in batches of eight to 40 in June to July and hatch after about 10 weeks. To survive and hatch, the eggs require a temperature of at least 21 °C (70 °F), but preferably 28 °C (82 °F), with high humidity. Areas of rotting vegetation, such as compost heaps, are preferred locations. The young are about 18 centimetres (7 in) long when they hatch and are immediately independent.[6]

Migration

editAfter breeding in summer, snakes tend to hunt and may range widely during this time, moving up to several hundred metres in a day.[6] Prey items tend to be large compared to the size of the snake, and this impairs the movement ability of the snake. Snakes that have recently eaten rarely move any significant distance and will stay in one location, basking to optimize their body temperature until the prey item has been digested. Individual snakes may only need two or three significant prey items throughout an entire season.

Ecdysis (moulting)

editEcdysis occurs at least once during the active season. As the outer skin wears and the snake grows, the new skin forms underneath the old, including the eye scales which may turn a milky blue/white colour at this time—referred to as being 'in blue'. The blue-white colour comes from an oily secretion between the old and new skins; the snake's coloration will also look dull, as though the animal is dusty. This process affects the eyesight of the snakes and they do not move or hunt during this time; they are also, in common with most other snakes, more aggressive. The outer skin is eventually sloughed in one piece (inside-out) and normal movement activity is resumed.[6]

Defence

editIn defence they can produce a garlic-smelling fluid from the anal glands, and feign death (thanatosis) by becoming completely limp[7] when they may also secrete blood (autohaemorrhage) from the mouth and nose.[8] They may also perform an aggressive display in defence, hissing and striking without opening the mouth. They rarely bite in defense and lack venomous fangs. When caught they often regurgitate the contents of their stomachs.

Grass snakes display a rare defensive behavior involving raising the front of the body and flattening the head and neck so that it resembles a cobra's hood, although the geographic ranges of grass snakes and of cobras overlap very little. However, the fossil record shows that the extinct European cobra Naja romani occurs in Miocene-aged strata of France, Germany, Austria, Romania, and Ukraine and thus overlapped with Natrix species including the extinct Natrix longivertebrata, suggesting that the grass snake's behavioral mimicry of cobras is a fossil behavior, although it may protect against predatory birds which migrate to Africa for the winter and encounter cobras there.[9]

Protection and threats

editThe species has various predator species, including corvids, storks, owls and perhaps other birds of prey, foxes, and the domestic cat.

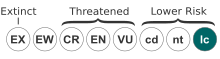

In Denmark it is protected,[10] as all five species of reptiles were protected in 1981. Two of the subspecies are considered critically endangered: N. n. cetti (Sardinian grass snake) and N. n. schweizeri.[1]

Mythology

editBaltic

editIn the Baltic mythology, the grass snake (Lithuanian: žaltys, Latvian: zalktis) is seen as a sacred animal.[11][12] It was frequently kept as a pet, living under a married couple's bed or in a special place near the hearth. Supposedly, snakes ate food given to them by hand.[13]

After the Christianization of Lithuania and Latvia, the grass snake still retained some mythological significance. In spite of the serpent's symbolic meaning as a symbol of evil in Christianity, in Latvia and Lithuania there were various folk beliefs, dating even to the late 19th century, that killing grass snakes might bring grave misfortune or that an injured snake will take revenge on the offender. The ancient Baltic belief of grass snakes as household spirits transformed into a belief that there is a snake (known or not to the inhabitants) living under every house; if it leaves, the house will burn down.[14] Common Latvian folk sayings include "who kills a grass snake, kills his happiness" and "when the Saulė sees a dead grass snake, she cries for 9 days".[15]

Well-known literary works based on these traditions include Lithuanian folk tale Eglė the Queen of Serpents (Eglė žalčių karalienė) and the Latvian folk fairytale "The grass snake's bride" (Zalkša līgava). These works include another common theme in Baltic mythology: that grass snakes wear crowns (note grass snake's yellow spots) and that there is a king of snakes who wears a golden crown. In some traditions the king of snakes changes every year; he drops his crown in spring and the other snakes fight for it (possibly based on the mating of grass snakes).[16]

Today grass snakes hold a meaning of house blessing among many Latvians and Lithuanians. One tradition is to put a bowl of milk near a snake's place of residence, although there is no evidence of a grass snake ever drinking milk.[17][18] Driven by late 19th century and 20th century Romantic nationalism, grass snake motifs in Latvia have gained a meaning of education and wisdom, and are common ornaments in the military, folk dance groups and education logos and insignia. They are also found on the Lielvārde Belt.[19] The grass snake has also become one of the main symbols of the Lithuanian neo-pagan movement Romuva.

Roman

editVirgil in his 29 BC Georgics (book III, lines 425-439: [1]) describes the grass snake as a large feared snake living in marshes in Calabria, eating frogs and fish.

Gallery

edit-

Hunting in early autumn, Sweden

-

Copulation

-

Grass snake in a pond in the nature resort in Zell am See, Salzburg (state), Austria.

-

Grass snake eating a frog in the forest in Poland

References

edit- ^ a b European Reptile & Amphibian Specialist Group (1996). "Natrix natrix". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T14368A4436775. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T14368A4436775.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Natrix natrix at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 3 May 2017.

- ^ a b Kindler, Carolin; Chèvre, Maxime; Ursenbacher, Sylvain; Böhme, Wolfgang; Hille, Axel; Jablonski, Daniel; Vamberger, Melita; Fritz, Uwe (2017), "Hybridization patterns in two contact zones of grass snakes reveal a new Central European snake species", Scientific Reports, 7 (1): 7378, Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.7378K, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07847-9, PMC 5547120, PMID 28785033

- ^ "Grass snake (Natrix natrix)". Wildsgk Arkive. Archived from the original on 2017-04-19. Retrieved 2017-04-18.

- ^ "Grass snake". The Woodland Trust. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Peter (1991). Ecology and vagility of the grass snake Natrix natrix helvetica (PhD thesis). University of Southampton.

- ^ Milius, Susan (October 28, 2006). "Why Play Dead?". Science News. 170 (18): 280–1. doi:10.2307/4017568. JSTOR 4017568. S2CID 85722243.

- ^ Gregory, Patrick T.; Leigh Anne Isaac; Richard A Griffiths (2007). "Death feigning by grass snakes (Natrix natrix) in response to handling by human "predators"". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 121 (2): 123–129. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.121.2.123. PMID 17516791. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ^ Pokrant, Felix (24 October 2017). "Grass snakes (Natrix natrix, N. astreptophora) mimicking cobras display a 'fossil behavior'". Vertebrate Zoology. 67 (2): 261–269. doi:10.3897/vz.67.e31593 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ "Snog". Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark. Miljø- og Fødevareministeriet. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Lūvena, Ivonne. "Egle — zalkša līgava. Pasaka par zalkti — baltu identitāti veidojošs stāsts" [Spruce – the Bride of the Grass Snake. The Folk Tale about Grass Snake as a Story of Baltic Identity]. In: LATVIJAS UNIVERSITĀTES raksti. n. 732: Literatūrzinātne, folkloristika, māksla. Rīga: LU Akadēmiskais apgāds, 2008. p. 16-22.

- ^ Eckert, Rainer (1998). "On the Cult of the Snake in Ancient Baltic and Slavic Tradition (based on language material from the Latvian folksongs)". Zeitschrift für Slawistik. 43 (1): 94–100. doi:10.1524/slaw.1998.43.1.94. S2CID 171032008.

- ^ Straižys, Vytautas (1997). "The Cosmology of the Ancient Balts". Journal for the History of Astronomy. Supplement. 28 (22): S57 – S81. Bibcode:1997JHAS...28...57S. doi:10.1177/002182869702802207. S2CID 117470993.

- ^ Britannica encyclopedia of world religions. Doniger, Wendy., Encyclopaedia Britannica, inc. Chicago, IL: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 2006. ISBN 9781593394912. OCLC 319493641.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Folklora Ailab".

- ^ "Ticējumi čūskas".

- ^ "Article "bringer of blessing"".

- ^ "Latvijas Daba".

- ^ "Zalkša zīme". Zīmju taka (in Latvian). 2014-01-31. Retrieved 2018-04-24.