Anchorage (Tanaina: Dgheyay Kaq'; Dgheyaytnu), officially the Municipality of Anchorage, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Alaska. With a population of 291,247 at the 2020 census,[5][9] it contains nearly 40 percent of the state's population. The Anchorage metropolitan area, which includes Anchorage and the neighboring Matanuska-Susitna Borough, had a population of 398,328 in 2020,[10] accounting for more than half the state's population. At 1,706 sq mi (4,420 km2) of land area, the city is the fourth-largest by area in the U.S.[11]

Anchorage

Dgheyay Kaq' (Tanaina) | |

|---|---|

| Municipality of Anchorage | |

|

| |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto: Big Wild Life | |

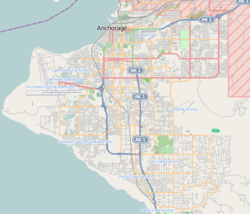

Interactive map of Anchorage | |

| Coordinates: 61°13′00″N 149°53′37″W / 61.21667°N 149.89361°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alaska |

| Borough | Anchorage |

| Settled | 1914 |

| Incorporated |

|

| Named for | The anchorage at the mouth of Ship Creek |

| Government | |

| • Body | Anchorage Assembly |

| • Mayor | Suzanne LaFrance |

| • Alaska Senate | Senators

|

| • Alaska House | Representatives

|

| Area | |

| 1,946.69 sq mi (5,041.89 km2) | |

| • Land | 1,706.89 sq mi (4,420.81 km2) |

| • Water | 239.80 sq mi (621.08 km2) |

| • Urban | 78.8 sq mi (204 km2) |

| Elevation | 102 ft (31 m) |

| Population | |

| 291,247 | |

• Estimate (2023)[6] | 286,075 |

| • Rank | |

| • Density | 170.6/sq mi (65.88/km2) |

| • Urban | 249,252 (US: 164th)[4] |

| • Urban density | 2,718.4/sq mi (1,049.6/km2) |

| • Metro | 398,807 (US: 137th) |

| Demonyms |

|

| GDP | |

| • Consolidated city-borough | $27.809 billion (2022) |

| • Metro | $31.569 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC-9 (AKST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-8 (AKDT) |

| ZIP code | 99501–99524, 99529–99530, 99599 |

| Area code | 907 |

| Geocode | 1398242 |

| FIPS code | 02-03000 |

| Climate | Dfc |

| Website | muni.org |

Anchorage is in Southcentral Alaska, at the terminus of the Cook Inlet, on a peninsula formed by the Knik Arm to the north and the Turnagain Arm to the south.[12] First settled as a tent city near the mouth of Ship Creek in 1915 when construction on the Alaska Railroad began, Anchorage was incorporated as a city in November 1920.[13][14] In September 1975, the City of Anchorage merged with the Greater Anchorage Area Borough, creating the Municipality of Anchorage.[15] The municipal city limits span 1,961.1 sq mi (5,079.2 km2), encompassing the urban core, a joint military base,[16] several outlying communities, and almost all of Chugach State Park.[17] Because of this, less than 10 percent of the Municipality (or Muni) is populated, with the highest concentration of people in the 100 square-mile area that makes up the city proper, on a promontory at the headwaters of the inlet, commonly called Anchorage, the City of Anchorage, or the Anchorage Bowl.[18]

Due to its location, almost equidistant from New York City, Tokyo, and Murmansk, Russia (straight over the North Pole), Anchorage lies within 10 hours by air of nearly 90 percent of the global north.[19][20] For this reason, Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport is a common refueling stop for international cargo flights and home to a major FedEx hub, which the company calls a "critical part" of its global network of services.[21][22]

Anchorage has won the All-America City Award four times: in 1956, 1965, 1984–85, and 2002, from the National Civic League.[23] Kiplinger has named it the United States' most tax-friendly city.[24]

History

editArchaeological evidence discovered at Beluga Point just south of Anchorage proper, along the Turnagain Arm, suggests that habitation of the Cook Inlet began 5,000 years ago by a group of Alutiiq people who arrived by kayak. As this population moved on, they were followed by a second wave of Alutiiq occupation beginning roughly 4,000 years ago, followed by a third wave around 2,000 years ago. Around 500 AD the Chugach Alutiiq were displaced by the arrival of Dena'ina Athabaskans, who entered through the mountain passes. The Dena'ina had no fixed settlements, migrating throughout the area with the seasonal changes, fishing along coastal streams and rivers in the summer, hunting moose, mountain goats, and Dall sheep in early fall, and picking berries in late fall. They tended to winter near trading junctions along common travel routes, where they traded with other Dena'ina and Ahtna tribes from nearby areas.[25]

Captain James Cook was among the first European explorers to map the Alaskan coastline, and many of the geographical features (mountains, islands, rivers, waterways, etc.) still bear the names he gave them. Cook was searching for the fabled Northwest Passage, a route that would provide a shorter means of reaching the Pacific from Europe than the difficult Northeast Passage around the north of Asia, or south around South America. On May 15, 1778, after enduring weeks of hard weather, Cook turned into an inlet between two landmarks he called Cape Douglas and Mount St. Augustine. He anchored his ship, HMS Resolution, at a place he called "Anchor Point" (later named "Anchorage" as another Anchor Point existed to the south near Homer, Alaska), near a creek he dubbed "Ship Creek" nestled between two large arms (waterways). Cook spent ten days exploring the inlet named after him. He first sent William Bligh to scout the north arm, where he met with the Dena'ina Natives of the Eklutna area, who told him the name of the Knik Arm and that it was not the Northwest Passage, but rather an outlet for two rivers (the Knik and Matanuska Rivers). Cook then sailed south to scout the other arm, and in a bad mood after running the Resolution aground on a sandbar on his way back out of the shallow waters, called it "River Turnagain", having found no sign of the passage there either.[26]

In the 19th century, Russian presence in South-Central Alaska was well-established. The Russians placed trading posts along Cook Inlet, such as the Shelikhov-Golikov Company's post at Niteh on the Palmer Flats (between the Knik and Matanuska Rivers), which in turn created small agricultural communities in Ninilchik, Seldovia, and Eklutna. The Russians also introduced diseases such as smallpox that had devastating effects on the local Native population, which plummeted by half just 10 years after the first census.[25]

In 1867, U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward brokered a deal to purchase Alaska from Imperial Russia for $7.2 million, or about two cents an acre ($129.1 million in 2023 dollars).[27] His political rivals lampooned the deal as "Seward's folly", "Seward's icebox" and "Walrussia". In 1888, gold was discovered along Turnagain Arm just south of modern-day Anchorage, leading to a new influx of prospectors, and small towns such as Spenard, Hope, Rainbow, Bird, Indian, and Girdwood began to spring up.

Alaska became an organized incorporated United States territory in 1912. Anchorage, unlike every other large town in Alaska south of the Brooks Range, was neither a fishing nor mining camp. The area surrounding Anchorage lacks significant economic metal ores. A number of Dena'ina settlements existed along Knik Arm for years. By 1911 the families of J. D. "Bud" Whitney and Jim St. Clair lived at the mouth of Ship Creek and were joined there by a young forest ranger, Jack Brown, and his bride, Nellie, in 1912.[28]

The city grew from its happenstance choice as a site for railroad construction to begin in 1914. The waters near Ship Creek were deep enough for barges and small ships to dock, and under the direction of Frederick Mears, it became a railroad-construction port for the Alaska Engineering Commission. The area near the mouth of Ship Creek, where the railroad headquarters was, quickly became a tent city. Anchorage formed at a time when proponents of Prohibition were gaining traction, and as part of an effort to stem the flow of the alcohol trade, at the direction of President Woodrow Wilson and with the symmetry of the US Army, a town site was mapped out on higher ground to the south of the tent city, with the condition that a person's land could be repossessed if caught breaking the alcohol laws.[25] Anchorage has been noted in the years since for its order and rigidity compared with other Alaska town sites.[14] In 1915, territorial governor John Franklin Alexander Strong encouraged residents to change the city's name to one that had "more significance and local associations".[29] In the summer of that year, residents held a vote to change the city's name; a plurality favored the name "Alaska City",[29] but the territorial government ultimately declined to change the city's name.[29] Anchorage was incorporated on November 23, 1920.[14]

Construction of the Alaska Railroad continued until its completion in 1923. The city's economy in the 1920s and 1930s centered on the railroad. Colonel Otto F. Ohlson, the Swedish-born general manager of the railroad for nearly two decades, became a symbol of residents' contempt due to the firm control he maintained over the railroad's affairs, which by extension became control over economic and other aspects of life in Alaska.

Between the 1930s and the 1950s, the city experienced massive growth as air transportation and the military became increasingly important. Aviation operations in Anchorage commenced along the firebreak south of town (today's Delaney Park Strip), which residents also used as a golf course. An increase in air traffic led to clearing of a site directly east of town site boundaries starting in 1929; this became Merrill Field, which served as Anchorage's primary airport during the 1930s and 1940s, until Anchorage International Airport superseded it in 1951. Merrill Field still sees a significant amount of general aviation traffic.

Elmendorf Air Force Base and the United States Army's Fort Richardson were constructed in the 1940s, and served as the city's primary economic engine until the 1968 Prudhoe Bay discovery shifted the thrust of the economy toward the oil industry.

The Good Friday earthquake of March 27, 1964, hit Anchorage hard at a magnitude of 9.2, killing 115 people and causing $116 million in damages ($750 million in 2023 dollars).[27][30][31][32] The earth-shaking event lasted nearly five minutes; most structures that failed remained intact for the first few minutes then failed with repeated flexing.[31][32] It was the world's fourth-largest earthquake in recorded history.[31][32] Broadcaster Genie Chance has been credited with holding Anchorage together, as she immediately rushed to the Anchorage Public Safety Building and stayed on the KENI airwaves for almost 24 continuous hours.[33] Chance, effectively designated as the public safety officer by the city's police chief,[34] was instrumental in Anchorage's relief and recovery efforts as she coordinated response efforts, connected urgent needs with available resources, disseminated information of available shelters and food sources, and passed messages among loved ones over the air, reuniting families.[33] Because the city and surrounding suburban area was built on top ground consisting of glacial silt, the prolonged shaking from the earthquake caused soil liquefaction, leading to massive cracks in roadways and collapse of large swaths of land. One of Anchorage's most affected residential areas, the Turnagain neighborhood, saw dozens of homes originally at 250 to 300 feet above sea level sink to sea level. Rebuilding and recovery dominated the remainder of the 1960s.

In 1968, ARCO discovered oil in Prudhoe Bay on the Alaska North Slope, and the resulting oil boom spurred further growth in Anchorage. In 1975, the City of Anchorage and the Greater Anchorage Area Borough (which includes Eagle River, Girdwood, Glen Alps, and several other communities) merged into the geographically larger Municipality of Anchorage[14] The city continued to grow in the 1980s, and capital projects and an aggressive beautification campaign took place.

Several attempts have been made to move Alaska's state capital from Juneau to Anchorage, or to a site closer to Anchorage. The motivation is straightforward: the "railbelt" between Anchorage and Fairbanks contains most of Alaska's population. Robert Atwood, owner of the Anchorage Times and a tireless booster for the city, championed the move. Alaskans rejected attempts to move the capital in 1960 and 1962, but in 1974, as Alaska's center of population moved away from Southeast Alaska and to the railbelt, voters approved it. Communities such as Fairbanks and much of rural Alaska opposed moving the capital to Anchorage for fear of concentrating more power in the state's largest city. As a result, in 1976, voters approved a plan to build a new capital city near Willow, about 70 mi (110 km) north of Anchorage. In the 1978 election, opponents to the move reacted by campaigning to defeat a nearly $1 billion bond issue to fund construction of the new capitol building and related facilities ($4 billion in 2023 dollars).[27] Later attempts to move the capital or the legislature to Wasilla, north of Anchorage, also failed.[35] Anchorage has over twice as many state employees as Juneau, and is to a considerable extent the center of Alaska's state and federal government activity.[36]

Geography

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

Anchorage is in Southcentral Alaska. At 61 degrees north, it lies slightly farther north than Oslo, Stockholm, Helsinki and Saint Petersburg, but not as far north as Reykjavík or Murmansk. It is northeast of the Alaska Peninsula, Kodiak Island, and Cook Inlet, due north of the Kenai Peninsula, northwest of Prince William Sound and the Alaska Panhandle, and nearly due south of Denali.

The city is on a strip of coastal lowland and extends up the lower alpine slopes of the Chugach Mountains. Point Campbell, the westernmost point of Anchorage on the mainland, juts out into Cook Inlet near its northern end, at which point it splits into two arms. To the south is Turnagain Arm, a fjord that has some of the world's highest tides. Knik Arm, another tidal inlet, lies to the west and north. The Chugach Mountains on the east form a boundary to development, but not to the city limits, which encompass part of the wild alpine territory of Chugach State Park.

The city's sea coast consists mostly of treacherous mudflats. Newcomers and tourists are warned not to walk in this area because of extreme tidal changes and the very fine glacial silt. Unwary victims have walked onto the solid seeming silt revealed when the tide is out and have become stuck in the mud. The two recorded instances of this occurred in 1961 and 1988.[37]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the municipality has an area of 1,961.1 square miles (5,079.2 km2); 1,697.2 square miles (4,395.8 km2) of which is land and 263.9 square miles (683.4 km2) of it is water. The total area is 13.5% water.

Boroughs and census areas next to the Municipality of Anchorage are Matanuska-Susitna Borough to the north, Kenai Peninsula Borough to the south and Chugach Census Area to the east. The Chugach National Forest, a national protected area, extends into the southern part of the municipality, near Girdwood and Portage.

Cityscape

editWildlife

editA diverse wildlife population exists within urban Anchorage and the surrounding area. Approximately 250 black bears and 60 grizzly bears live in the area. Bears are regularly sighted within the city. Moose are also a common sight; in the Anchorage Bowl, there is a summer population of approximately 250 moose, increasing to as many as 1,000 during the winter. They are a hazard to drivers, with over 100 moose killed by cars each year. Two people were stomped to death, in 1993 and 1995, in Anchorage.[38] Cross-country skiers and dog mushers using city trails have been charged by moose on numerous occasions; the Alaska Department of Fish and Game has to kill some individual aggressive moose in the city every year. Dall sheep are often viewed quite close to the road at Windy Point.[39] Approximately thirty northern timber wolves reside in the Anchorage area. In 2007, several dogs were killed by timber wolves while on walks with their owners.[40][41] There are also beaver dams in local creeks and lakes, and sightings of foxes and kits in parking lots close to wooded areas in the spring are common. Along the Seward Highway headed toward Kenai, there are common sightings of beluga whales in the Turnagain Arm. Lynxes are occasionally sighted in Anchorage as well. Within the Municipality there are also a number of streams that host salmon runs. Fishing for salmon at Ship Creek next to downtown is popular in the summer.

Climate

edit| Anchorage | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Anchorage has a subarctic climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfc on the borderline of Dfb, Trewartha Eolo bordering on Dclo) but with strong maritime influences that lead to a relatively moderate climate,[43] in contrast to the much more continental Fairbanks. Most of its precipitation falls in late summer. Average daytime summer temperatures range from approximately 55 to 78 °F (13 to 26 °C); average daytime winter temperatures are about 5 to 30 °F (−15.0 to −1.1 °C). Anchorage has a frost-free growing season that averages slightly over 101 days. According to local folklore, when a native plant called fireweed goes to seed after a full bloom, the first snowfall of winter is 6 weeks away.[44]

Average January low and high temperatures at Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport (ANC) are 11 to 23 °F (−12 to −5 °C) with an average winter snowfall of 75.5 in (192 cm).[45] The 2011–2012 winter had 134.5 in (341.6 cm), which made it the[46] snowiest winter on record, topping[46][47] the 1954–1955 winter with 132.8 in (337.3 cm). The coldest temperature ever recorded at the original weather station at Merrill Field on the East end of 5th Avenue was −38 °F (−38.9 °C) on February 3, 1947.[nb 1]

Summers are mild (although cool compared to the contiguous US and even interior Alaska), and it can rain frequently, although not abundantly. Average July low and high temperatures are 52 to 66 °F (11 to 19 °C) and the highest reading ever recorded was 90 °F (32.2 °C) on July 4, 2019.[48] The average annual precipitation at the airport is 16.63 in (422 mm).[45] Anchorage's latitude causes summer days to be very long and winter daylight hours to be very short. The city is often cloudy during the winter, which further decreases the amount of sunlight experienced by residents.[49]

The coldest daily maximum recorded in Anchorage was −19 °F (−28 °C) in January 1989, while the coldest daily maximum on average between 1991 and 2020 was 1 °F (−17 °C).[45] Warm summer nights do not occur even with the bayside location and extensive daylight; the mildest night on record was 63 °F (17 °C)[when?]. The mean temperature is 59 °F (15 °C).[45]

Due to its proximity to active volcanoes, ash hazards are a significant, though infrequent, occurrence. The most recent notable volcanic activity centered on the multiple eruptions of Mount Redoubt during March–April 2009, resulting in a 25,000 ft (7,600 m) high ash cloud as well as ash accumulation throughout the Cook Inlet region. Previously, the most active recent event was an August 1992 eruption of Mount Spurr, which is 78 mi (126 km) west of the city.[50] The eruption deposited about 3 mm (0.1 in) of volcanic ash on the city. The clean-up of ash resulted in excessive demands for water and caused major problems for the Anchorage Water and Wastewater Utility.

The average temperature of the sea ranges from 35.8 °F (2.1 °C) in February to 53.1 °F (11.7 °C) in August.[51]

| Climate data for Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport, Alaska (1991−2020 normals,[52] extremes 1953−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 50 (10) |

49 (9) |

53 (12) |

69 (21) |

77 (25) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

82 (28) |

73 (23) |

64 (18) |

54 (12) |

51 (11) |

90 (32) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 41.8 (5.4) |

42.7 (5.9) |

44.2 (6.8) |

56.3 (13.5) |

69.5 (20.8) |

74.5 (23.6) |

76.0 (24.4) |

73.7 (23.2) |

65.0 (18.3) |

54.8 (12.7) |

42.7 (5.9) |

42.3 (5.7) |

77.7 (25.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 22.7 (−5.2) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

33.0 (0.6) |

45.1 (7.3) |

56.3 (13.5) |

63.4 (17.4) |

66.2 (19.0) |

64.0 (17.8) |

55.7 (13.2) |

42.0 (5.6) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

44.1 (6.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 16.9 (−8.4) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

25.8 (−3.4) |

37.5 (3.1) |

48.1 (8.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

59.6 (15.3) |

57.5 (14.2) |

49.3 (9.6) |

36.3 (2.4) |

23.6 (−4.7) |

19.4 (−7.0) |

37.6 (3.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 11.0 (−11.7) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

18.6 (−7.4) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

40.0 (4.4) |

48.4 (9.1) |

52.9 (11.6) |

50.9 (10.5) |

42.9 (6.1) |

30.7 (−0.7) |

18.3 (−7.6) |

13.8 (−10.1) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −9.3 (−22.9) |

−3.6 (−19.8) |

1.2 (−17.1) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

30.7 (−0.7) |

40.5 (4.7) |

46.7 (8.2) |

42.7 (5.9) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

16.1 (−8.8) |

0.8 (−17.3) |

−4.9 (−20.5) |

−13.2 (−25.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −34 (−37) |

−28 (−33) |

−24 (−31) |

−4 (−20) |

17 (−8) |

33 (1) |

36 (2) |

31 (−1) |

19 (−7) |

−5 (−21) |

−21 (−29) |

−30 (−34) |

−34 (−37) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.75 (19) |

0.86 (22) |

0.69 (18) |

0.43 (11) |

0.65 (17) |

1.02 (26) |

1.82 (46) |

2.93 (74) |

3.10 (79) |

1.82 (46) |

1.19 (30) |

1.16 (29) |

16.42 (417) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.4 (31) |

13.4 (34) |

11.0 (28) |

4.0 (10) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

5.6 (14) |

12.6 (32) |

18.2 (46) |

77.9 (198) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 16.4 (42) |

19.0 (48) |

19.9 (51) |

12.7 (32) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

3.2 (8.1) |

8.8 (22) |

14.7 (37) |

24.5 (62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.1 | 7.9 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 8.6 | 11.7 | 14.4 | 14.9 | 11.5 | 9.8 | 10.8 | 115.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.8 | 7.8 | 6.1 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 7.7 | 10.8 | 47.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.4 | 71.4 | 66.1 | 64.3 | 61.6 | 65.6 | 71.4 | 75.1 | 75.9 | 74.5 | 77.1 | 77.1 | 71.1 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 8.1 (−13.3) |

11.1 (−11.6) |

15.4 (−9.2) |

24.1 (−4.4) |

33.4 (0.8) |

42.4 (5.8) |

48.6 (9.2) |

47.8 (8.8) |

40.6 (4.8) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

15.3 (−9.3) |

10.6 (−11.9) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 82.9 | 120.5 | 195.8 | 235.3 | 288.7 | 274.7 | 250.1 | 203.9 | 159.8 | 117.1 | 80.6 | 51.8 | 2,061.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 41 | 48 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 48 | 44 | 42 | 41 | 38 | 37 | 30 | 46 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[45][53][54] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[55] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Anchorage | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 36.9 (2.8) |

35.8 (2.1) |

36.1 (2.3) |

37.5 (3.0) |

42.4 (5.8) |

47.7 (8.8) |

52.4 (11.3) |

53.1 (11.7) |

51.6 (10.9) |

47.5 (8.6) |

43.0 (6.1) |

39.6 (4.2) |

43.6 (6.5) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 7.0 | 9.0 | 12.0 | 15.0 | 18.0 | 19.0 | 18.0 | 16.0 | 13.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 12.5 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[55] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Campbell Airstrip (Anchorage Alaska) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 20 (−7) |

26 (−3) |

35 (2) |

45 (7) |

58 (14) |

66 (19) |

68 (20) |

65 (18) |

55 (13) |

41 (5) |

26 (−3) |

22 (−6) |

44 (7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 2 (−17) |

4 (−16) |

9 (−13) |

22 (−6) |

33 (1) |

41 (5) |

47 (8) |

44 (7) |

35 (2) |

22 (−6) |

7 (−14) |

5 (−15) |

23 (−5) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 10.0 (25) |

16.0 (41) |

18.0 (46) |

9.0 (23) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

9.0 (23) |

11.0 (28) |

2.0 (5.1) |

75.2 (191.61) |

| Source: NOAA[45] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 1,856 | — | |

| 1930 | 2,277 | 22.7% | |

| 1940 | 3,495 | 53.5% | |

| 1950 | 11,254 | 222.0% | |

| 1960 | 44,397 | 294.5% | |

| 1970 | 48,081 | 8.3% | |

| 1980 | 174,431 | 262.8% | |

| 1990 | 226,338 | 29.8% | |

| 2000 | 260,283 | 15.0% | |

| 2010 | 291,826 | 12.1% | |

| 2020 | 291,247 | −0.2% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 286,075 | [56] | −1.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[57][58] | |||

Anchorage first appeared on the 1920 U.S. Census.[59] It incorporated that same year and in 1975 it was consolidated with its borough.

2020 census

editAt the 2020 census, Anchorage had 291,247 people.[9] Racial makeup was 63.8% White (57.1% were non-Hispanic or Latino), 10.0% Asian, 9.1% American Indian or Alaska Native, 6.0% African American, and 8.4% from two or more races; 9.4% of the people were Hispanic or Latino. The age distribution was 6.9% of the population under the age of 5; 24.0% under 18; 64.3% aged 18–64; and 11.7% aged 65 and up. Males were 50.9% of the people; females, 49.1%. Veterans were 9.3%, and 10.9% of the people were born outside the United States. There were 119,276 housing units and 106,567 households; the average household size was 2.69 persons. In 17.8% of households, a language other than English was spoken at home. In 95.9% of households there was a computer; 90.0% of households had broadband Internet connections. 93.9% of the population had a high school diploma or higher with 36.1% having a Bachelor's degree or higher. 8.4% of the population under the age of 65 had a disability with 11.1% of the same age group having no health insurance. 68.5% of the population were in the civilian labor force. The median household income was $84,928 and the per capita income from May 2019–April 2020 was $41,415. The poverty rate was 9.5%.

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[60] | Pop 2010[61] | Pop 2020[62] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 181,982 | 182,814 | 158,232 | 69.92% | 62.64% | 54.33% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 14,667 | 15,308 | 13,777 | 5.64% | 5.25% | 4.73% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 18,326 | 22,047 | 22,480 | 7.04% | 7.55% | 7.72% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 14,208 | 23,208 | 27,281 | 5.46% | 7.95% | 9.37% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 2,335 | 5,776 | 9,844 | 0.90% | 1.98% | 3.38% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 583 | 562 | 1,922 | 0.22% | 0.19% | 0.66% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 13,383 | 20,050 | 31,273 | 5.14% | 6.87% | 10.74% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 14,799 | 22,061 | 26,438 | 5.69% | 7.56% | 9.08% |

| Total | 260,283 | 291,826 | 291,247 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

editAccording to the 2010 census, Anchorage had a population of 291,826 and its racial and ethnic composition was as follows:[63][64][65]

- White: 66.0% (62.6% non-Hispanic)

- Two or more races: 8.1%

- Asian: 8.1% (3.3% Filipino, 1.2% Korean, 1.1% Hmong, 0.41% Chinese, 0.35% Thai)

- American Indian and Alaska Natives: 7.9% (1.4% Iñupiat, 1.1% Yup'ik, 0.8% Aleut)

- Black or African American: 5.6%

- Other race: 2.3%

- Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders: 2.0% (1.4% Samoan)

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race): 7.6% (4.4% Mexican, 1.2% Puerto Rican, 0.71% Dominican)

| Racial composition | 2010[66] | 1990[67] | 1970[67] | 1950[67] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 66.0% | 80.7% | 87.2% | 97.2% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 62.6% | 78.7% | n/a | n/a |

| Black or African American | 5.6% | 6.4% | 5.9% | n/a |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 7.9% | 6.4% | 1.8% | 1.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 7.6% | 4.1% | 2.4%[68] | n/a |

| Asian | 8.1% | 4.8% | 1.0% | n/a |

According to the 2010 census, the largest national ancestry groups were as follows: 17.3% German, 10.8% Irish, 9.1% English, 6.9% Scandinavian (3.6% Norwegian, 2.2% Swedish, 0.6% Danish) and 5.6% French/French Canadian ancestry.[69][70]

According to the 2010 American Community Survey, approximately 82.3% of residents over the age of five spoke only English at home. Spanish was spoken by 3.8% of the population; speakers of other Indo-European languages made up 3.0% of the population; those who spoke Asian and Pacific Islander languages at home were 9.1%; and speakers of other languages made up 1.8%.[71]

In 2010, there were 291,826 people, 107,332 households and 70,544 families residing in the municipality. The population density was 171.2 per square mile (66.1/km2). There were 113,032 housing units at an average density of 59.1 per square mile (22.8/km2). There were 107,332 households, out of which 33.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.4% were married couples living together, 11.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.3% were non-families. 24.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.64 and the average family size was 3.19. The age distribution was 26.0% under 18, 11.2% from 18 to 24, 29.0% from 25 to 44, 26.6% from 45 to 64, and 7.2% who were 65 or older. The median age was 32.9 years. 50.8% of the population was male and 49.2% were female.[72]

The median income for a household in the municipality was $73,004, and the median income for a family was $85,829. The per capita income for the municipality was $34,678. About 5.1% of families and 7.9% of the population were below the poverty line.[73][74] Of the city's population over the age of 25, 33.7% held a bachelor's degree or higher, and 92.1% had a high school diploma or equivalent.[69]

Languages

editIn 2010, 83.7% (220,304) of Anchorage residents aged five and older spoke only English at home, while 4.5% (11,769) spoke Spanish, 2.5% (6,654) Tagalog, 1.6% (4,108) various Pacific Island languages, 1.4% (3,636) various Native American/Alaska Native languages, 1.1% (2,994) Korean, 0.6% (1,646) German, 0.6% (1,502) Hmong, 0.5% (1,307) Russian, and Japanese was spoken as a main language by 0.5% (1,185) of the population over the age of five. In total, 16.3% (43,010) of Anchorage's population aged five and older spoke a mother language other than English.[75]

As of September 7, 2006[update], 94 languages were spoken by students in the Anchorage School District.[76]

Economy

editAnchorage's largest economic sectors include transportation, military, municipal, state and federal government, tourism, corporate headquarters (including regional headquarters for multinational corporations) and resource extraction. Large portions of the local economy depend on Anchorage's geographical location and surrounding natural resources. Anchorage's economy traditionally has seen steady growth, though not quite as rapid as many places in the lower 48 states. With the notable exception of a real estate-related crash in the mid-to-late 1980s, which saw the failure of numerous financial institutions, it does not experience as much pain during economic downturns.[citation needed]

The Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport (TSAIA) is the world's fourth busiest airport for cargo traffic, surpassed only by Memphis, Hong Kong, and Shanghai Pudong. This traffic is strongly linked to Anchorage's location along great circle routes between Asia and the lower 48. In addition, the airport has an abundant supply of jet fuel from in-state refineries in North Pole and Kenai. This jet fuel is transported to the Port of Anchorage, then by rail or pipeline to the airport.

The Port of Anchorage receives 95 percent of all goods destined for Alaska. Ships from Totem Ocean Trailer Express and Horizon Lines arrive twice weekly from the Port of Tacoma in Washington. Along with handling these activities, the port is a storage facility for jet fuel from Alaskan refineries, which is used at both TSAIA and Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER).

The existing port was substantially built in the late 1950s and is reaching the end of its useful life. Beginning in 2017, the Port of Anchorage is undertaking an extensive 7-year Anchorage Port Modernization Project[77] to upgrade its aging infrastructure, support larger deeper draft vessels, and future proof the port seismically and environmentally for another 75 years.

The United States military has two large installations, Elmendorf Air Force Base and Fort Richardson, which originally stemmed from the branching off of the U.S. Air Force from the U.S. Army following World War II. In a cost-cutting effort initiated by the 2005 BRAC proceedings, the bases were combined. JBER was created, which also incorporated Kulis Air National Guard Base near TSAIA. The combination of these three bases employ approximately 8,500 civilian and military personnel. These individuals along with their families comprise approximately ten percent of the local population. During the Cold War, Elmendorf became an important base due to its proximity to the Soviet Union, particularly as a command center for numerous forward air stations established throughout the western reaches of Alaska (most of which have since closed).

While Juneau is the official state capital of Alaska, more state employees reside in the Anchorage area. Approximately 6,800 state employees work in Anchorage compared to about 3,800 in Juneau. The State of Alaska purchased the Bank of America Center (which it renamed the Robert B. Atwood Building) to house most of its offices, after several decades of leasing space in the McKay Building (now the McKinley Tower) and later the Frontier Building.

The resource sector, mainly petroleum, is arguably Anchorage's most visible industry, with many high-rise buildings bearing the logos of large multinationals such as Hilcorp and ConocoPhillips. While field operations are centered on the Alaska North Slope and south of Anchorage around Cook Inlet, the majority of offices and administration are found in Anchorage. The headquarters building of ConocoPhillips Alaska, a subsidiary of ConocoPhillips, is in downtown Anchorage.[78] It is also the tallest building in Alaska. Many companies who provide oilfield support services are likewise headquartered outside of Anchorage but maintain a substantial presence in the city, most notably Arctic Slope Regional Corporation and CH2M Hill.

Four small airlines, Alaska Central Express,[79] Era Aviation,[80] Hageland Aviation Services,[81] and PenAir, are headquartered in Anchorage.[82] Alaska Airlines (at one point headquartered in Anchorage, but now headquartered in the Seattle area), has major offices and facilities at TSAIA, including the offices of the Alaska Airlines Foundation.[83] Prior to their respective dissolutions, airlines MarkAir, Reeve Aleutian Airways and Wien Air Alaska were also headquartered in Anchorage.[84][85][86] The Reeve Building, at the corner of West Sixth Avenue and D Street, was spared the wrecking ball when the city block it sits on was cleared to make way for the Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall, and was incorporated into the mall's structure. In 2013, Forbes named Anchorage among its list of Best Places for Business and Careers.[87]

Five Alaska Native regional corporations are based in Anchorage: The Aleut Corporation, Bristol Bay Native Corporation, Calista Corporation, Chugach Alaska Corporation, and Cook Inlet Region, Inc.

Anchorage does not levy a sales tax. However, it charges a 12% bed tax on hotel stays and an 8% tax on car rentals.[88] Since about 2000, in response to strong revenue and occupancy rates, major hotel developers from the Lower 48 have been building new hotels along C Street from International Airport Road to just north of Tudor Road, with two more to open in 2017, making this half-mile stretch of C Street a new "hotel row".[89] From Anchorage people can easily head south to popular fishing locations on the Kenai Peninsula or north to locations such as Denali National Park and Fairbanks.

Arts

editLocated next to Town Square Park in downtown Anchorage, the Alaska Center for the Performing Arts is a three-part complex that hosts numerous performing arts events each year. The facility can accommodate more than 3,000 people. In 2000, nearly 245,000 people visited 678 public performances. It is home to eight resident performing arts companies and has featured mega-musicals performed by visiting companies. The center also hosts the International Ice Carving Competition as part of the Fur Rendezvous festival in February.

The Anchorage Concert Association brings 20 to 30 events to the community each year, including Broadway shows like Disney's The Lion King, Les Misérables, Mamma Mia!, The Phantom of The Opera, West Side Story, and others. The Anchorage Chamber Music Festival draws international guest artists and faculty to perform a summer concert series, and teach a Chamber Intensive program for young musicians. The Sitka Summer Music Festival presents an "Autumn Classics" festival of chamber music for two weeks each September on the campus of Alaska Pacific University. Orchestras include the Anchorage Symphony Orchestra and the Anchorage Youth Symphony.

Annually in January, the Anchorage Folk Festival takes place at the University of Alaska Anchorage, featuring concerts, dances, and workshops with featured guest artists and over 130 performances by volunteer singers, dancers, musicians, and storytellers.

- Alaska Native Heritage Center[90]

- Alaska Museum of Natural History[91]

- Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum

- Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center[92]

- Oscar Anderson House Museum[93]

- Wells Fargo Alaska Heritage Library & Museum[94]

The city of Anchorage provides three municipal facilities large enough to hold major events such as concerts, trade shows and conventions. Downtown facilities include the Alaska Center for the Performing Arts, William A. Egan Civic & Convention Center and the recently completed Dena'ina Civic and Convention Center, which will be connected via skybridge to form the Anchorage Civic & Convention District. The Sullivan Arena hosts sporting events as well as concerts and annual trade shows.

Sports

edit| Team | Sport | League | Began | Folded | Venue (capacity) | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchorage Bucs | Baseball | Alaska Baseball League | 1981 | Mulcahy Stadium (3500) | 0 | |

| Anchorage Glacier Pilots | Baseball | Alaska Baseball League | 1969 | Mulcahy Stadium (3500) | 5 (1969, 1971, 1986, 1991, 2001) | |

| Chugiak-Eagle River Chinooks | Baseball | Alaska Baseball League | Relocated from Fairbanks in 2010 | Loretta French Park (600) | 1 (2007) | |

| Alaska Aces | Hockey | ECHL | 1989 | 2017 | Sullivan Arena (6,290 (seated), 6,490 (with standing room)) | 3 (2006, 2011, 2014) |

| Anchorage Wolverines | Hockey | North American Hockey League | 2021 | Ben Boeke Ice Arena | 0 | |

| Anchorage Northern Knights | Basketball | Continental Basketball Association | 1977 | 1982 | West Anchorage High School Gymnasium | 1 (1980) |

National attention focuses on Anchorage on the first Saturday of each March, when the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race kicks off with its ceremonial start downtown on Fourth Avenue. Anchorage is also home to the Fur Rendezvous Open World Championship Sled Dog Races, a three-day dog sled sprint event consisting of three timed races of 25.5 mi (41.0 km) each. Held each February, the event is part of the annual Fur Rendezvous, a winter sports carnival.

Anchorage is home to three teams in the Alaska Baseball League: the Anchorage Bucs and Anchorage Glacier Pilots, which both play at Mulcahy Stadium, and the Chugiak-Eagle River Chinooks based at Lee Jordan Field in Chugiak.[95]

Anchorage has no professional sports teams. The most recent to call the city home was the Alaska Aces of the ECHL. The Aces were very successful during their time in Anchorage, claiming three league titles, four conference championships, and eight division championship during their 29-year history (1989–2017). The Aces affiliated with various National Hockey League teams, including the Calgary Flames, Minnesota Wild, and Vancouver Canucks. After the 2016–17 season, the team ceased operations and was sold to a group in Portland, Maine, where it became the Maine Mariners in the 2018–19 season. In 2021, the NAHL approved the addition of an expansion team in Anchorage.[96] The expansion team, named the Anchorage Wolverines, began competing in the Midwest Division for the 2021–22 season.

The University of Alaska Anchorage Seawolves are a member of the National Collegiate Athletic Association. UAA has Division I teams in gymnastics and hockey, as well as several other Division II teams. UAA sponsors the annual Great Alaska Shootout, an annual NCAA Division I basketball tournament featuring colleges and universities from across the United States along with the UAA team.

Anchorage is the finish line for the Sadler's Ultra Challenge wheelchair race.

The city hosts four rugby clubs: the Bird Creek Barbarians RFC, the Anchorage Thunderbirds,[97] the Mat Valley Maulers RFC, and the Spenard Green Dragons.[98] The season runs from April through September.

The Anchorage Northern Knights gained national attention when they joined the eight-team Eastern Basketball Association in 1977, a league whose nearest competitor was 5,000 mi (8,000 km) from Anchorage. The Knights captured the 1979–80 league championship, and featured several players who would play in the NBA, most notably Brad Davis, a future player and broadcaster for the Dallas Mavericks. They competed in the renamed Continental Basketball Association for five seasons until the economic recession ended their run in 1982.

The city was the U.S. candidate for hosting the 1992 and 1994 Winter Olympics, but lost to Albertville, France, and Lillehammer, Norway, respectively. Anchorage is a premier cross-country skiing city, in terms of density of groomed trails within the urban core. There are 105 mi (169 km) of maintained ski trails in the city, some of which reach downtown. The same trail system also provides access to Chugach State Park, a 495,000-acre (200,000 ha) high alpine park.[99] The Tour of Anchorage is an annual 50-kilometer ski race within the city[100] and was the Host for the 2009 and 2010 US Senior National Cross Country Ski Championship.[101]

Anchorage is also home to Alaska's first WFTDA flat track women's roller derby league, the Rage City Rollergirls.[102]

The Anchorage Football Stadium is also a noteworthy sports venue.

The 1989 World Junior Ice Hockey Championships was played in Anchorage.

Parks and recreation

editParks, gardens, and wildlife refuges

edit- Alaska Native Heritage Center[103]

- The Alaska Botanical Garden has over 900 species of hardy perennials and 150 native plant species[104]

- Alaska Zoo[105]

- Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center[106]

- Anchorage Coastal Wildlife Refuge

- Delaney Park Strip

- Kincaid Park

- Point Woronzof Park

- Flattop Mountain Recreation Area

- Westchester Lagoon/Margaret Eagan Sullivan Park

Many of Anchorage's parklands are interconnected with green belts that follow the lakes and streams that form the natural watershed, creating water/parkland (blue/green) interfaces in the pluvial flood zones, which helps minimize the risk of floods damaging homes and businesses.[107]

Recreational facilities

edit- Arctic Valley Ski Area[108]

- Alyeska Resort[109]

- Hilltop Ski Area[110]

- Kincaid Park[111]

- Tony Knowles Coastal Trail

Points of interest

edit- Moose's Tooth Pub & Pizzeria, a pub and pizzeria ranked 3rd best in the United States[112]

- Anchorage Museum

Government and politics

edit| Year | Office | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Senator | Murkowski 42–32% |

| House | Young 65–34% | |

| Governor | Parnell 57–41% | |

| 2012 | President | Romney 53–43% |

| House | Young 61–32% | |

| 2014 | Senator | Begich 48–47% |

| House | Young 47–46% | |

| Governor | Walker 49–45% | |

| 2016 | President | Trump 47–42% |

| Senator | Murkowski 45–25% | |

| House | Young 48–40% | |

| 2018 | House | Galvin 51–49% |

| Governor | Begich 48–48% | |

| 2020 | President | Biden 49–47% |

| Senator | Sullivan 50–47% | |

| House | Galvin 51–49% |

Anchorage is governed by an elected mayor and 11-member assembly, with the assistance of a city manager. These positions are nonpartisan (as are all municipal elected offices in Alaska): no candidates officially run under any party banner. All 11 members are elected from districts known as sections. Five of the sections elect two members from designated seats, while the remaining section elects one member. Before the 1980 United States Census, the single-member section was the one centered around the northern Anchorage communities of Chugiak and Eagle River. Since then, the area encompassing Downtown Anchorage and surrounding neighborhoods has served as the city's single-member section. The mayor (along with members of the school board) is elected in a citywide vote. In practice, major candidates' party affiliation and political ideology are usually well known and highlighted by local media for the purpose of framing debate. The city's mayor is Suzanne LaFrance. Along with seven sister cities in the SCI program[clarification needed], Anchorage has a cultural exchange program with Montenegro.

In the 2017 municipal election, Christopher Constant and Felix Rivera became the first openly gay candidates elected to Anchorage public office.[113][114]

Anchorage generally leans toward Republican candidates in both state and presidential elections. But since the establishment of the municipality in 1975, there have been two Democratic mayors (Tony Knowles and Mark Begich), each of whom was elected to two consecutive terms and later to statewide office. Downtown, Girdwood, and much of both the west and east parts of town trend Democratic. Areas closest to the military bases, including Eagle River, and south Anchorage are the municipality's most Republican areas. Midtown is relatively moderate. In 2020, Joe Biden became the first Democrat to win Anchorage since Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 68,169 | 46.97% | 70,933 | 48.87% | 6,031 | 4.16% |

| 2016 | 61,066 | 46.97% | 53,953 | 41.50% | 14,999 | 11.54% |

| 2012 | 66,430 | 53.06% | 54,026 | 43.15% | 4,745 | 3.79% |

| 2008 | 76,959 | 56.91% | 55,221 | 40.84% | 3,040 | 2.25% |

| 2004 | 76,807 | 59.93% | 47,676 | 37.20% | 3,681 | 2.87% |

| 2000 | 67,959 | 57.15% | 34,726 | 29.20% | 16,235 | 13.65% |

| 1996 | 51,627 | 52.79% | 32,638 | 33.37% | 13,538 | 13.84% |

| 1992 | 45,253 | 41.38% | 32,889 | 30.07% | 31,227 | 28.55% |

| 1988 | 50,508 | 61.16% | 29,412 | 35.62% | 2,659 | 3.22% |

| 1984 | 60,987 | 68.70% | 25,158 | 28.34% | 2,627 | 2.96% |

| 1980 | 38,956 | 59.10% | 15,186 | 23.04% | 11,774 | 17.86% |

| 1976 | 31,884 | 61.46% | 17,136 | 33.03% | 2,857 | 5.51% |

| 1972 | 23,918 | 63.31% | 10,859 | 28.74% | 3,003 | 7.95% |

| 1968 | 13,833 | 45.10% | 13,005 | 42.40% | 3,831 | 12.49% |

| 1964 | 9,051 | 40.07% | 13,537 | 59.93% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 11,119 | 53.71% | 9,581 | 46.29% | 0 | 0.00% |

Voting trends show that Downtown Anchorage votes Democratic in large margins, while Spenard, Turnagain/Inlet View, and University/Airport Heights are relatively moderate and swing in elections. The remaining Anchorage areas have traditionally trended Republican.[116] In 2018, Anchorage began conducting municipal elections by mail (as directed by the assembly in 2015) and had the highest voter turnout in the city's history.[117]

Anchorage-Eagle River sends 16 representatives (as of 2018[update], nine Republicans and seven Democrats) to the 40-member Alaska House of Representatives and eight senators (five Republicans and three Democrats) to the 20-member Senate. When seats from the neighboring Mat-Su Borough are added, more than half the Alaska state legislature comes from the Anchorage metropolitan area. This is often used as an argument for moving the state capital from Juneau to the Anchorage area.

Public safety

editWith a reported strength of 383 sworn officers, the Anchorage Police Department is the largest police department in the state, serving an area of 159 square miles with a population of 300,950.[118] Until 2016, Alaska State Troopers provided policing for the southern regions of Anchorage along Turnagain Arm. After their withdrawal, Girdwood contracted with the neighboring city of Whittier for its policing,[119] and the following year APD provided contract policing to other Turnagain Arm communities.[120] The Fire & EMS Operations Division of the Anchorage Fire Department (AFD) includes thirteen fire stations with over 300 personnel covering three rotating 24-hour shifts. Additionally, there are volunteer fire departments in Girdwood and Chugiak and fire departments on Elmendorf Air Force Base and Fort Richardson, as well as the Airport Police and Fire Department.[121]

| Violent crimes[nb 2] per 100,000 pop. |

Property crimes[nb 3] per 100,000 pop. | |

|---|---|---|

| Anchorage[122] | 837.7 | 3,518.0 |

| Alaska[123] | 638.8 | 2,852.5 |

| U.S. cities, pop. 100,000–249,999[124] |

519.6 | 3,846.8 |

| U.S. cities, pop. 250,000–499,999[124] |

757.7 | 4,216.6 |

| U.S. total[123] | 403.6 | 2,941.9 |

Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports

| ||

In 2010, Anchorage reported 837.7 violent crimes per 100,000 population and 3,518.0 property crimes per 100,000 population (see table). Anchorage's crime rate, both for violent and property crimes, is higher than for Alaska as a whole or for the U.S. as a whole. When compared with U.S. cities of similar size, Anchorage has a slightly higher rate of violent crime and a slightly lower rate of property crime. Anchorage, and Alaska in general, have very high rates of sexual assault in comparison with the rest of the country, with Anchorage's annual rate of forcible rapes over three times as high as for the U.S. as a whole. In 2010, the rate of rape for Anchorage was 90.9 per 100,000 population,[122] while the U.S. rate was 27.5 per 100,000 population.[123] Alaska Natives are victimized at a much higher rate than their representation in the population.[125]

The Anchorage Community Survey, a public survey conducted in 2004–05 by the Justice Center at University of Alaska Anchorage, found that overall, Anchorage residents are fairly satisfied with the performance of the Anchorage Police Department.[126] Most survey respondents perceived the justice system to be "somewhat effective" or "very effective" at apprehending and prosecuting criminal suspects, bringing about just outcomes, and reducing crime.[127]

Education

editPublic education in all of Anchorage municipality, including Eagle River, Chugiak, Fort Richardson and Elmendorf Air Force Base, is managed by the Anchorage School District,[128] the 87th largest district in the United States, with nearly 50,000 students attending 98 schools.[129] There are also a number of choices in private education, including both religious and non-denominational schools.

Anchorage has four higher-education facilities that offer bachelor's or master's degrees: the University of Alaska Anchorage,[130] Alaska Pacific University, Charter College,[131] and the Anchorage campus of Texas-based Wayland Baptist University. The University of Alaska Fairbanks also has a small Center for Distance Education downtown. Other continuing education facilities in Anchorage include the Grainger Leadership Institute, Nine Star Enterprises, CLE International, Nana Worksafe, and PackBear DBA Barr & Co.

Ninety percent of Anchorage's adults have high-school diplomas, 65 percent have attended one to three years of college, and 17 percent hold advanced degrees.[citation needed]

Anchorage has the most ethnically diverse schools in the United States, including the three most diverse high schools, the three most diverse middle schools, and the 19 most diverse elementary schools. Even the least diverse schools in Anchorage rank in the top 1% nationally.[132]

The Chugach School District operates neighborhood schools in Valdez–Cordova Census Area, Alaska, as well as the supplementary Voyage to Excellence Residential School in Anchorage; its board office is in Anchorage.[133] The Aleutian Region School District, which operates schools in areas of the Aleutian Islands, has its district administrative offices in Anchorage.[134]

Media

editAnchorage's leading newspaper is the Anchorage Daily News,[135] a citywide daily newspaper. Other newspapers include the Alaska Star,[136] serving primarily Chugiak and Eagle River, the Anchorage Press,[137] a free weekly covering mainly cultural topics, and The Northern Light,[138] the student newspaper of the University of Alaska Anchorage. Anchorage's major network television affiliates are KTUU 2 (NBC), KTBY 4 (Fox), KAUU 5 (CBS/MyNetworkTV), KAKM 7 (PBS), KTVA 11 (Rewind TV), KYUR 13 (ABC/CW), and KDMD 33 (Ion/Telemundo/MeTV). Anchorage is one hour behind the Pacific Time Zone, and receives the same network feed as the West Coast. Weekday primetime runs from 7 to 10 pm. Effectively, programs are viewed at the same local hour as those in the Central Time Zone. The city's only cable television provider is General Communication, Inc. (GCI). However, Dish Network and DirecTV offer satellite television service in Anchorage and the surrounding area using East Coast feeds.

There are many radio stations in Anchorage; see List of radio stations in Alaska for more information.

Health and utilities

editProvidence Alaska Medical Center on Providence Drive in Anchorage is the largest hospital in Alaska and is part of Providence Health & Services in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, and California. It features the state's most comprehensive range of services. Providence Health System has a history of serving Alaska, beginning when the Sisters of Providence of Montreal first brought health care to Nome in 1902. As the territory grew during the following decades, so did efforts to provide care. Hospitals were opened in Fairbanks in 1910 and Anchorage in 1937.

Alaska Regional Hospital on DeBarr Road opened in 1958 as Anchorage Presbyterian Hospital, downtown at 825 L Street. This predecessor to Alaska Regional was a joint venture between local physicians and the Presbyterian Church. In 1976 the hospital moved to its present location on DeBarr Road, and is now a 254-bed licensed and accredited facility. Alaska Regional has expanded services and in 1994, Alaska Regional joined with HCA, one of the nation's largest healthcare providers.

Alaska Native Medical Center on Tudor Road provides medical care and therapeutic health care to Alaska natives—229 tribes—at the Anchorage site and at 15 satellite facilities throughout the state. ANMC specialists also travel to clinics in the bush to provide care. The 150-bed hospital is also a teaching center for the University of Washington's regional medical education program. ANMC houses an office of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium and Southcentral Foundation jointly own and manage ANMC.

Electric power in the Anchorage area is provided by Chugach Electric Association, a nonprofit, member-owned cooperative founded in 1948. From 1932 to 2020, the Municipality of Anchorage operated its own electric utility, Municipal Light & Power (ML&P). Historically, ML&P served the older, more urbanized regions of the city, while Chugach served newer areas of town, suburbs, and rural areas. Chugach acquired ML&P in 2020, with the sale finalized in October.[139] Post-acquisition, the Chugach cooperative had over 92,000 members.[140]

Most homes have natural gas-fueled heat. ENSTAR Natural Gas Company is the sole provider for Anchorage, servicing some 90-percent of the city's population.

The Municipality of Anchorage owns and operates the Anchorage Water and Wastewater Utility, serving some 55,000 customer accounts with water from Eklutna Lake, which is mainly meltwater from Eklutna Glacier. Anchorage Municipal Solid Waste Services and Anchorage Refuse conduct trash removal in the city depending on location.

Transportation

editMajor highways

edit- AK-1 passing through downtown Anchorage

- AK-3 branching off from AK-1 in Gateway, 35 miles northeast of Anchorage city

Alaskans do not use numerical route designations in everyday discourse, preferring the named designations—in this case the Seward Highway (for AK-1 south of the city), the Glenn Highway (for AK-1 northeast of the city), and the Parks Highway (for AK-3).

Highway to Highway

editOn and off since the 1960s, the Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities, in coordination with the Federal Highway Administration and the Municipality of Anchorage (or the lineal predecessors of those entities), have been exploring the concept of a roadway connecting the endpoints of the Seward and Glenn highways. The project is called "Highway to Highway", and the most recent concept for this project is that of a "trenched" freeway through the heart of Anchorage.

Highway to Highway was included in the 2005 Long Range Transportation Plan, and would cost at least $575 million ($862 million in 2023 dollars).[27] – by far the largest urban infrastructure project in Alaska's history.

Public transit

editAnchorage has a bus system called People Mover,[141] with a hub downtown and satellite hubs at Dimond Center and Muldoon Mall. The People Mover provides carpool organization services. The public paratransit service known as AnchorRides[142] provides point-to-point accessible transportation services to seniors and those who experience disabilities.

Rail

editThe Alaska Railroad offers year-round freight service along the length of its rail system between Seward (the southern terminus of the system), Fairbanks (the northern terminus of the system), and Whittier (a deep water, ice-free port). Daily passenger service is available during summer (May 15 – September 15), but is reduced to one round-trip per week between Anchorage and Fairbanks during the winter.[143][144][145] Passenger terminals exist at Talkeetna, Denali National Park, Fairbanks, and several other locations. These communities are also served by bus line from Anchorage. The Ship Creek Shuttle connects downtown with the Ship Creek area, including stops at the Alaska Railroad depot.

Anchorage also is conducting a feasibility study on a commuter rail and light rail system.[146][147] For the commuter rail system, Anchorage would use existing Alaska Railroad tracks to provide service to Whittier, Palmer, Seward, Wasilla, and Eagle River.

Air transport

editThe Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport, 6 mi (9.7 km) south of downtown Anchorage, is the airline hub for the state, served by many national and international airlines, including Seattle-based Alaska Airlines as well as many intrastate airlines and charter air services. The airport is the primary international air freight gateway in the nation. By weight, five percent of the value of all United States international air cargo moved through Anchorage in 2008.[148] During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was briefly the busiest airport in the United States due to sustained volume of cargo flights through Alaska while passenger travel sharply decreased in other American airports.[149] Next to Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport is Lake Hood Seaplane Base, the largest Seaplane Base in the world. Merrill Field, a general aviation airport on the edge of downtown, was the 87th-busiest airport in the nation in 2010.[150] There are also ten smaller private (mostly Department of Transportation) general aviation airports within the city limits.[151]

Notable people

editSister cities

editAnchorage has seven sister cities.[152]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ In an average winter, the first snow happens in mid-October and begins to thaw in mid-March, but snow can sometimes be present until the end of April. The high temperature would usually drop below freezing at the beginning of November. The average first frost happens during the first half of September and the average last frost happens during the second half of May. In March 2002, a record snow storm, 26.7 inches, hit Anchorage."Temperature Records for Anchorage Alaska" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ Includes of murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault.

- ^ Includes burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson.

References

edit- ^ Cochran, Jessica. "Alaska Cultural Connections: Los Anchorage". Archived from the original on March 15, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ Cole, Dermot (September 25, 2011). "'Los Anchorage' may seem a world apart, but it's not alien territory". Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". United States Census Bureau. January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product: All Industries in Anchorage Municipality County, AK". www.fred.stlouisfed.org.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Anchorage, AK (MSA)". www.fred.stlouisfed.org.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts Anchorage Municipality (County), Alaska; Anchorage municipality, Alaska". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "2020 Census Data - Cities and Census Designated Places" (Web). State of Alaska, Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Jegede, Abayomi (July 2, 2021). "Top 10 Largest Cities in USA by Land Area". Trendrr. Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Alaska Geography". Archived from the original on October 18, 2014.

- ^ Naske, Claus-M. (1987). Alaska: A History of the 49th State. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8061-2573-2.

- ^ a b c d "Community Database Online, Anchorage". Alaska Division of Community and Regional Affairs. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ "Municode Library". Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Fulton, William; Daniels, Jessica; de la Peña, Benjamin (2008). "Case Studies in Smart Growth Implementation – Anchorage, Alaska" (PDF). Smart Growth Leadership Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- ^ State of Alaska. "Chugach State Park, Alaska State Parks". alaska.gov. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "Anchorage Bowl Land Use Plan Map – Anchorage Bowl Comprehensive Plan – Community Discussion Draft 2/29/16" (PDF). Municipality of Anchorage. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "Anchorage Int'l Airport Serves as Pit Stop for Global Cargo Carriers – Airport Improvement Magazine". airportimprovement.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ "Iceland airline's 'over the top' flights will connect Alaska to Europe". Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Latest Global News" (PDF). About FedEx. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "Alaskan airport set to be the new stopover between Europe and Asia-Pacific". Independent.co.uk. February 9, 2021. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "National Civil League All-America winners by state". National Civic League. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ "Top 10 Tax-Friendly Cities". Kiplinger. April 24, 2007. Archived from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c Aunt Phil's Trunk: Bringing Alaska's history alive! Volume 3 by Laurel Bill, Phyllis Carlson – Aunt Phil's Trunk LLC 2016 pp. 1–5

- ^ Captain Cook: Master of the Seas by Frank McLynn, Yale University Press, 2011[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ a b c d Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ A Gathering of Saints in Alaska: an informal chronicle of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the state of Alaska. Alaska: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1983. p. 306.

- ^ a b c Jones, Preston (2010). City for Empire: An Anchorage History, 1914–1941. University of Alaska Press. pp. 169–70. ISBN 978-1602230859. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS): NCEI/WDS Global Historical Tsunami Database. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (1972). "Search Parameters Year = 1964 Location contains 'prince'". NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. doi:10.7289/V5PN93H7.

- ^ a b c "The Great Alaska Earthquake of 1964". Geophysical Institute, UAF. Alaska Earthquake Information Center. Archived from the original on April 7, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Historic Earthquakes, Prince William Sound, Alaska". USGS. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ a b "Genie Chance and the Great Alaska Earthquake". The New York Times. May 22, 2020. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "When a Quake Shook Alaska, a Radio Reporter Led the Public Through the Devastating Crisis". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "Alaska History and Cultural Studies – Governing Alaska – The Capital of Alaska". akhistorycourse.org. Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "State of Alaska Workforce Profile: Fiscal Year 2023" (PDF). doa.alaska.gov. Alaska Department of Administration. Retrieved December 13, 2024.

- ^ Kaniut, Larry (1999). Danger Stalks the Land: Alaskan Tales of Death and Survival. St. Martins Press. pp. 2–6, 287–91. ISBN 978-1466824898. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "Moose Stomps Man to Death on College Campus". Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Alaska Highway Drives from Anchorage". Alaska.org. Archived from the original on September 20, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

- ^ "Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game, Living with Wildlife in Anchorage: a Cooperative Planning Effort". State of Alaska. April 2000. Archived from the original on January 5, 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ "North Side wolf pack attacks, kills dogs". Anchorage Daily News. December 11, 2007. Archived from the original on October 19, 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Data". Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ "Climate". Archived from the original on July 31, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ^ "Fireweed: Countdown to Winter". Human Flower Project. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "Record-breaking Snowfall in Anchorage". ktuu.com. April 7, 2012. Archived from the original on April 8, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ "Snowfall Records for Anchorage Alaska" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ Alaska Bakes with Alltime Heat Records Archived March 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

Weather Underground. June 21, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2016 - ^ "For November, December, and January, average monthly percent possible sunshine (the hours of direct sunlight experienced, divided by the possible hours of sunlight for the location) is below 35%". Climate.umn.edu. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012."For an explanation of the concept "percent possible sunlight". Data Through 2005 Average Percent Possible Sunshine at National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2006.

- ^ "Mt. Spurr's 1992 Eruptions". Alaska Volcano Observatory. Archived from the original on December 9, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ "Anchorage Water Temperature – United States – Sea Temperatures". World Sea Temperatures. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ "Station: Anchorage INTL AP, AK". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 14, 2023. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "WMO climate normals for Anchorage/INTL, AK 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 14, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Anchorage, Alaska, USA - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 1. ISBN 978-0810830332

- ^ "Population" (PDF). U.S. Decennial Census 1920. United States Census Bureau. p. 544. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Anchorage municipality, Alaska". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Anchorage municipality, Alaska". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Anchorage municipality, Alaska". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau". FactFinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on May 21, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau". FactFinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau". FactFinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Anchorage Municipality, Alaska". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 3, 2011. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ From 15% sample

- ^ a b "U.S. Census Bureau". FactFinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau". FactFinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau". FactFinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau". FactFinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Anchorage (municipality) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". Quickfacts.census.gov. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau". FactFinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 13, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Anchorage Municipality County, Alaska". Modern Language Association. Archived from the original on August 15, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "About the Anchorage School District – Languages our students speak". ASD Online – Anchorage School District. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- ^ "Anchorage Port Modernization Project". portofanc.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ "North Slope National Petroleum Reserva Alaska 2008/2009 Exploration Drilling Program Archived September 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." ConocoPhillips Alaska. November 2008. Page 1 (1/8). Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived June 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." Alaska Central Express. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived August 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." Era Aviation. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived November 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Hageland Aviation Services. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived December 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." PenAir. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ "The Alaska Airlines Foundation Archived March 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine." Alaska Airlines. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ "World Airline Directory." Flight International. March 22–28, 1995. 761 Archived March 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "World Airline Directory." Flight International. March 30, 1985. 111 Archived March 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^ "About Us". Reeve Aleutian Airways. Archived from the original on August 27, 1999. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ "Best Places For Business and Careers – Forbes". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 8, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Alaska Taxable 2008" (PDF). Alaska Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development. January 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ "'Hotel Row' springs up in Midtown Anchorage, updated September 28, 2016". Alaska Dispatch News. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ "Alaska Native Heritage Center". Alaskanative.net. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ "Alaska Museum of Natural History". Alaskamuseum.org. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ "The Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center". Anchoragemuseum.org. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ "anchoragehistoric.org". anchoragehistoric.org. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ Alaskan Heritage Museum Archived August 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Wells Fargo. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Chugiak–Eagle River Chinooks – Alaska Baseball League". cerchinooks.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "NAHL team in Anchorage, Alaska approved for the 2021–22 season". North American Hockey League. March 22, 2021. Archived from the original on March 22, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.