Valparaiso (/ˌvælpəˈreɪzoʊ/ VAL-pə-RAY-zoh), colloquially Valpo, is a city in and the county seat of Porter County, Indiana, United States.[4] The population was 34,151 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Chicago metropolitan area.

Valparaiso, Indiana | |

|---|---|

Lincolnway in downtown Valparaiso | |

| Nickname: Valpo | |

| Motto: "Vale of Paradise" | |

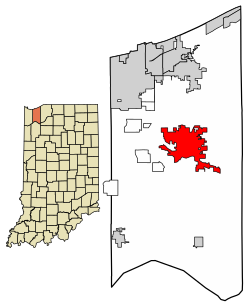

Location of Valparaiso in Porter County, Indiana. | |

| Coordinates: 41°28′34″N 87°02′25″W / 41.47611°N 87.04028°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Indiana |

| County | Porter |

| Township | Center |

| Incorporated | February 29, 1835 |

| Named for | Valparaíso, Chile |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jon Costas (R) |

| Area | |

• Total | 16.43 sq mi (42.57 km2) |

| • Land | 16.39 sq mi (42.44 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.12 km2) 0.32% |

| Elevation | 791 ft ([2] m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 34,151 |

| • Density | 2,084.16/sq mi (804.68/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 46383-46385 |

| Area code | 219 |

| FIPS code | 18-78326[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2397114[2] |

| Website | www |

History

editThe site of present-day Valparaiso was included in the purchase of land from the Potawatomi people by the U.S. Government in October 1832. Chiqua's town or Chipuaw[5] was located a mile east of the current Courthouse along the Sauk Trail. Chiqua's town existed from or before 1830 until after 1832.[6] The location is just north of the railroad crossing on State Route 2 and County Road 400 North.

Located on the ancient Native American trail from Rock Island to Detroit, the town had its first log cabin in 1834.[7] Established in 1836 as Portersville, county seat of Porter County, it was renamed to Valparaiso (meaning "Vale of Paradise" in Old Spanish) in 1837 after Valparaíso, Chile, near which the county's namesake David Porter battled in the Battle of Valparaiso during the War of 1812.[8] The city was once called the "City of Churches" due to the large number of churches located there at the end of the 19th century. Valparaiso Male and Female College, one of the earliest higher education institutions admitting both men and women in the country, was founded in Valparaiso in 1859, but closed its doors in 1871 before reopening in 1873 as the Northern Indiana Normal School and Business Institute. In the early 20th century, it became Valparaiso College, then Valparaiso University. It was initially affiliated with the Methodist Church but after 1925 with the Lutheran University Association (which has relationships both with the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, and with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) and expanded significantly after World War II.

From the 1890s until 1969, there were no African-American residents in Valparaiso. This has been attributed to Valparaiso being a sundown town.[9][10] There was also substantial activity by the Ku Klux Klan, which negotiated to purchase Valparaiso University in 1923.[11] The first African-American family to move to Valparaiso faced intimidation and eventually left the city when a visiting relative was murdered.[9][12] In recent years, the city's racial composition has diversified.

Valparaiso also has a long history of being a transportation hub for the region. In 1858, the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railroad reached Valparaiso, connecting the city directly to Chicago. By 1910, an interurban railway connected the city to Gary, Indiana. Today, while the city no longer has a passenger train station, it is still very much a part of the "Crossroads of America" due to its proximity to I-65, I-80, I-90, and I-94. Additionally, the Canadian National railroad still runs freight on the tracks, including through the downtown area.

Until 1991, Valparaiso was the terminal of Amtrak's Calumet commuter service.

Geography

editThe city is situated at the junctions of U.S. Route 30, State Road 2, and State Road 49.

According to the 2010 census, Valparaiso has a total area of 15.578 square miles (40.35 km2), of which 15.53 square miles (40.22 km2) (or 99.69%) is land and 0.048 square miles (0.12 km2) (or 0.31%) is water.[13]

Topography

editThe city is situated on the Valparaiso Moraine.

Glaciation has left numerous features on the landscape here. Kettle lakes and knobs make up much of this hilly area of Northwest Indiana. The Pines Ski Area is the only remaining kame in the city; the other one is under the university's Chapel of the Resurrection, however, grading of land in that area makes that particular kame almost nonexistent. Many glacial erratics can be found throughout the city. The moraine has left the city with mostly clay soil.

Climate

edit| Climate data for Valparaiso, Porter County Regional Airport, Indiana (1991-2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 66 (19) |

72 (22) |

87 (31) |

90 (32) |

98 (37) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

96 (36) |

89 (32) |

77 (25) |

70 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 33.9 (1.1) |

37.9 (3.3) |

49.1 (9.5) |

62.1 (16.7) |

73.0 (22.8) |

82.2 (27.9) |

85.0 (29.4) |

83.3 (28.5) |

77.6 (25.3) |

65.1 (18.4) |

50.5 (10.3) |

38.8 (3.8) |

61.5 (16.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 26.2 (−3.2) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

39.8 (4.3) |

50.9 (10.5) |

61.7 (16.5) |

71.4 (21.9) |

74.6 (23.7) |

72.8 (22.7) |

66.2 (19.0) |

54.6 (12.6) |

42.3 (5.7) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

51.8 (11.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 18.4 (−7.6) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

39.7 (4.3) |

50.5 (10.3) |

60.5 (15.8) |

64.2 (17.9) |

62.3 (16.8) |

54.8 (12.7) |

44.2 (6.8) |

34.2 (1.2) |

24.5 (−4.2) |

42.1 (5.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −26 (−32) |

−21 (−29) |

−7 (−22) |

10 (−12) |

26 (−3) |

33 (1) |

42 (6) |

38 (3) |

27 (−3) |

18 (−8) |

2 (−17) |

−20 (−29) |

−26 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.38 (60) |

2.24 (57) |

2.63 (67) |

3.74 (95) |

4.59 (117) |

4.33 (110) |

4.10 (104) |

3.57 (91) |

2.92 (74) |

3.93 (100) |

3.26 (83) |

2.58 (66) |

40.27 (1,024) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 14.6 (37) |

5.5 (14) |

6.7 (17) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

2.3 (5.8) |

9.4 (24) |

40 (101.56) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 12.6 | 8.4 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 13.4 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 9.1 | 10 | 10.9 | 11 | 126.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA (temperatures)[14] (precipitation and snow at water pumping station)[15] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: The Weather Channel (records),[16] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 522 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,698 | 225.3% | |

| 1870 | 2,765 | 62.8% | |

| 1880 | 4,461 | 61.3% | |

| 1890 | 5,090 | 14.1% | |

| 1900 | 6,280 | 23.4% | |

| 1910 | 6,987 | 11.3% | |

| 1920 | 6,518 | −6.7% | |

| 1930 | 8,079 | 23.9% | |

| 1940 | 8,736 | 8.1% | |

| 1950 | 12,028 | 37.7% | |

| 1960 | 15,227 | 26.6% | |

| 1970 | 20,020 | 31.5% | |

| 1980 | 22,247 | 11.1% | |

| 1990 | 24,414 | 9.7% | |

| 2000 | 27,428 | 12.3% | |

| 2010 | 31,730 | 15.7% | |

| 2020 | 34,151 | 7.6% | |

| Source: US Census Bureau | |||

2010 census

editAs of the census[17] of 2010, there were 31,730 people, 12,610 households, and 7,117 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,043.1 inhabitants per square mile (788.8/km2). There were 13,506 housing units at an average density of 869.7 units per square mile (335.8 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 89.9% White, 3.3% African American, 0.3% Native American, 2.1% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.2% from other races, and 2.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7.1% of the population.

There were 12,610 households, of which 28.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.6% were married couples living together, 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.9% had a male householder with no wife present, and 43.6% were non-families. 34.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 2.99.

The median age in the city was 33.4 years. 21.3% of residents were under the age of 18; 15.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.9% were from 25 to 44; 22.8% were from 45 to 64; and 13.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.6% male and 51.4% female.

2000 census

editAs of the census[3] of 2000, there were 27,428 people, 10,867 households, and 6,368 families residing in the city. The population density was 971.6 people/km2 (2,516 people/sq mi). There were 11,559 housing units at an average density of 409.4 units/km2 (1,060 units/sq mi). The racial makeup of the city was 94.35% White, 1.60% African American, 0.23% Native American, 1.49% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.79% from other races, and 1.52% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.34% of the population.

There were 10,867 households, out of which 28.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.9% were married couples living together, 9.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.4% were non-families. 33.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 21.2% under the age of 18, 17.4% from 18 to 24, 28.1% from 25 to 44, 20.2% from 45 to 64, and 13.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $45,799, and the median income for a family was $60,637. Males had a median income of $46,452 versus $26,544 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,509. About 4.8% of families and 9.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 8.1% of those under age 18 and 7.5% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

edit- Featured in Valparaiso, a play by Don DeLillo

- The Valparaiso Downtown Commercial District, Washington Street Historic District, and the Banta Neighborhood feature many historic homes; architectural designs include, Italianate, Arts & Crafts, and English/Cottswold.

Live theater

edit- Chicago Street Theatre, run by the local Community Theater Guild.[18]

- The Memorial Opera House, a musical theater venue.

- Valparaiso Theatrical Company, a non-profit community theatre group focused on providing fund-raising opportunities for other non-profit organizations through theatrical performance.[19]

Museums

edit- Brauer Museum of Art at Valparaiso University

- Museum of Fire Fighting[20]

- Porter County Museum, also known as the Old Jail Museum[21]

City fairs

editThe city holds two major festivals every year: the Popcorn Festival and the Porter County Fair. The Popcorn Festival is held on the first Saturday after Labor Day. It honors Orville Redenbacher, a former resident who built a popcorn factory there. Redenbacher participated in most of the festival's parades until his death in 1995. The festival also features foot racing events and multiple concerts in addition to typical fair activities. The Porter County Fair consists of carnival attractions and hosts a variety of shows such as a demolition derby, motocross races, and live musical performances.

Public library

editValparaiso has a public library, a branch of the Porter County Public Library System.[22]

Historic buildings and districts

edit- Porter County Courthouse replaced an earlier brick building in 1883. The current building is 128 feet by 98 feet. It was built with a square tower rising out of the center. The tower was 168 feet tall with a clock on each side. A fire in 1934 damaged in the interior requiring the removal of the tower.[23]

National Register of Historic Places

editThere are a number of buildings and districts in the city listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Conrad and Catherine Bloch House

- Haste-Crumpacker House

- Heritage Hall

- Immanuel Lutheran Church

- Dr. David J. Loring Residence and Clinic

- William McCallum House

- Charles S. and Mary McGill House

- Porter County Jail and Sheriff's House

- Porter County Memorial Opera Hall

- David Garland Rose House

- DeForest Skinner House

- Valparaiso Downtown Commercial District

- Washington Street Historic District (Valparaiso, Indiana)

Parks and recreation

editValparaiso has an extensive city park district. In 2005 there were 13 parks with another in the planning stages.[24]

Parks

edit200 East (East McCord Rd) – a community park with a playground; where many of the city's legendary athletes played football as youngsters. Football at 200 East Park is a staple for young kids growing up in the neighborhood.

Bicentennial Park (Burlington Beach Road & Campbell St) – Provides a full range of activities, including a playground, basketball courts, ball diamond and picnic shelters. A prairie restoration is under way in the north half of the park.

Central Park Plaza (Lincolnway and Lafayette St) – is the centerpiece of the Downtown Valparaiso revitalization and opened the summer of 2011. It has an outdoor amphitheater for concerts and other special events as well as a splash pad in the center of the park for kids to play.

Fairgrounds Park (Calumet & Evans Avenues) – Has the largest complex of ball diamonds and soccer fields in the city. A playground and basketball court are available. Numerous city sports leagues use Fairgrounds Park for their games and tournaments. The park is surrounded by a paved walking circuit that is well occupied on nice days.

Foundation Meadows (Campbell Street & Bullseye Lake Rd) – One of the city's newer parks.

Glenrose South (1500 Roosevelt Road) – Provides several ball diamonds and when school is out, Thomas Jefferson Middle Schools track is available for those interested in walking. Glenrose South has been the home of the Valparaiso Fourth of July Fireworks display and celebration since 2005.

Jessee-Pifer Park (Elmhurst & Madison Streets) – a community park with a basketball court and picnic shelter.

Kirchhoff Miller Woods, (Roosevelt Road & Institute St – a community park that provides for basketball, baseball, tennis, picnicking and a playground.

Ogden Gardens/Forest Park (Campbell Street and Harrison Blvd) – Ogden Gardens is the home of the city's botanical garden. The Campbell Street end is a formal garden with a variety of planting that bloom throughout the year. The Gazebo is a favorite place for weddings, wedding pictures and high school prom pictures. A Japanese garden is included with a 22,000-gallon Koi pond. Forest Park is to the west with an open grassy picnic area below a wooded picnic area with a shelter.

Rock Island (Coolwood Dr &, Frontage Rd) is a "tourist attraction" found in front of the Strack & Van Til grocery store just off of the US 30 highway. The curb that splits the right and left turn lanes has been responsible for a number car crashes and accidents. Over the weekend between May 17 and May 19 of 2024, community members decorated the curb with rocks, signs, traffic cones, and other miscellaneous decor, including a flamingo and a blanket for one of the rocks. This has since been considered an inside joke, featuring its own Google reviews as an official tourist attraction.[25]

Rogers-Lakwood Park (Meridian Road (N Campbell Street)) – Provide opportunities for swimming, fishing, and hiking trails. It is connected to the north side communities of Valparaiso by the Campbell Street Bike Trail (hiking and biking).

Tower Park (Evans Ave and Franklin St.) is a community park that offers basketball, baseball, tennis, pickleball, picnicking, and a playground. During winter months, one of the basketball courts is turned into the community skating rink.[26]

Valplayso/Glenrose North (Glendale Blvd and Roosevelt Rd) is the home of Valplayso, a community-designed and community-built playground. At the other end of the parking lot are several ball fields. Separated from Glenrose South by only the Middle Schools track, Glenrose North hosts over half of the community during the Fourth of July Celebration.

West Side Park (Joliet Rd) is a community park with a ball field and a playground.

Will Park (Morgan Blvd and Brown St) is a community park with a basketball court, playground, and picnic shelter.

Golf

edit- Valparaiso Country Club

- Forest Park

- Creekside

- Mink Lake (Closed)

- The Course at Aberdeen

Bike trails

editValparaiso is building a series of bike trails across the city. Currently, (March 2012) most of the identified bike routes are part of the county's system of recommended roads and streets.[27]

Biking and hiking

editCampbell Street Bikeway runs from Rogers-Lakewood Park south 2.5 miles (4.0 km) to Vale Park Road (CR 400 N). It continues south on the opposite side of Campbell St. base Valparaiso High School, ending 2 miles (3.2 km) south at Ogden Gardens (Harrison Blvd).

At Vale Park, it connects to the Vale Park trail to Valparaiso Street 1 mile (1.6 km). A new bike loop 3 miles (4.8 km) is being built that circles north along Valparaiso Street to Bullseye Lake Rd, east to Cumberland Crossing (not open to the public (2008), south to Vale Park, turning west to on Vale Park to return to the corner of Vale Park and Valparaiso Street.

At Glendale, the Campbell Street Bikeway connects to the Glendale cross town bike lane. These travel east 2 miles (3.2 km) on Glendale, ending on North Calumet at the Walgreens corner.

Government

editValparaiso has an elected mayor, an elected clerk-treasurer, and an elected council. All of these positions are elected for four-year terms in November of the year before a presidential election year and assumes office on January 1.[28]

Education

editHigher education

editValparaiso University was founded in 1859, and occupies 310 acres (130 ha) on the south side of the city near downtown. The university is a cultural center of the city, hosting venues such as the Brauer Museum of Art, with more than 2,700 pieces of 19th- and 20th century American art.

Ivy Tech operates one of its 23 regional campuses in the city. From 2006 until 2016, Purdue University North Central had a two-building satellite campus in Valparaiso.[29]

Primary and secondary education

edit- Public schools

Valparaiso Community Schools cover all of Center Township and most of the city of Valparaiso (that which is within Center Township) - Valparaiso Community Schools

- Valparaiso High School

- Porter County Career and Technical Center

- Benjamin Franklin Middle School

- Thomas Jefferson Middle School

- Central Elementary

- Cooks Corner Elementary School

- Heavilin Elementary

- Flint Lake Elementary School

- Thomas Jefferson Elementary School

- Memorial Elementary

- Northview Elementary School

- Parkview Elementary

- East Porter County Schools

- Washington Township Middle-High School; serves part of the city of Valparaiso

- Valparaiso Community Schools

- Private schools

- Immanuel Lutheran School (K-8)

- Montessori School of Valparaiso

- Saint Paul's Catholic School (K-8)

Media

editNewspapers

editValparaiso is served by two regional newspapers:

- The Times of Northwest Indiana (or NWI Times), was founded in 1906 and is the second largest of Indiana's 76 daily newspapers. It is based on Munster.[30]

- The Post-Tribune of Northwest Indiana was founded in 1907, serving the Northwest Indiana region. The Post-Tribune is owned by Tribune Company and is based in Merrillville.[31]

Magazines

editNorth Valpo Neighbors and South Valpo Neighbors are published in Valparaiso.

Radio

editThe primary local radio stations are WLJE 105.5 FM "Indiana 105", which broadcasts country music, WAKE 1500 AM, which plays adult standards, and WVLP 98.3 FM "ValpoRadio", a non-profit, low power FM community radio station. Valparaiso formerly had a fourth local station, WNWI 1080 AM, which relocated to Oak Lawn, Illinois in 1998 and is now a Chicago-market station. Radio is usually from the Chicago market.

Infrastructure

editValparaiso gets all of its water from wells that draw water from depths between 90 and 120 feet (37 m). The supply is treated with chlorine solution to remove the iron.[32] Valparaiso also has three sewer retention basins.

Valparaiso's energy is provided by NIPSCO. The Schaeffer Power Plant is located south of Valparaiso, in Wheatfield.[33]

A city bus service, the V-Line, was founded in 2007. It operates between downtown, the university, shopping centers, the city's northern neighborhoods, and Dune Park station of the Northern Indiana Commuter Transit District.

On October 6, 2008, Valparaiso inaugurated an express bus service to and from Chicago, Illinois called ChicaGo DASH. Buses depart Valparaiso on weekday mornings and return from Chicago in the evenings.

Valparaiso is served by four highways. U.S. Route 30 is the major east–west artery on the southern side of the city. Indiana State Road 49, the major north–south artery, connects with Chesterton, Indiana and the Indiana Toll Road. Indiana Route 130 runs northwest to Hobart, Indiana. Indiana State Road 2, which connects South Bend and Lowell, passes through the southeast corner of the city.[34]

Three railroads pass through the city. The Norfolk Southern Railway operates on the tracks that were previously the Nickel Plate Road, the Canadian National is the former Grand Trunk Western Railroad and the Chicago, Fort Wayne and Eastern Railroad operates on the tracks that were previously used by the Pennsylvania Railroad.[35]

Notable people

edit- Newton Arvin, literary critic[36]

- John L. Bascom, politician[37]

- Harry Benham, actor

- Beulah Bondi, actress[38]

- Mary Blatchley Briggs (1846– 1910), writer and women's organizer

- Kevin L. Brown, former Major League Baseball (MLB) player[39]

- Mark N. Brown, astronaut[40]

- Josephine Cochrane, invented and patented the modern dishwasher

- Bryce Drew, professional basketball player in the National Basketball Association (NBA)[41]

- Michael Essany, reality television talk show host and author[42]

- Gina Fattore, producer and writer of Dawson's Creek, Gilmore Girls, Parenthood and showrunner of Dare Me

- Chris Funk, guitarist for The Decemberists[43]

- Henry C. Gordon, astronaut[44]

- Mark A. Heckler, 18th president of Valparaiso University

- Zach Holmes, new Jackass member[45]

- Robbie Hummel, professional basketball player in the NBA since 2012[46]

- Samuel Austin Kendall, politician[47]

- Mike Kellogg, retired Moody Radio announcer[48]

- Hub Knolls, former pitcher in Major League Baseball

- Heather Kuzmich, 4th runner-up of America's Next Top Model, Cycle 9[49]

- Earl F. Landgrebe, politician, staunch defender of Richard Nixon[50]

- Charles F. Lembke, architect and contractor. He built many downtown area buildings.[51]

- David E. Lilienthal, politician[52]

- Sean Manaea, professional baseball player in MLB[53][54]

- Orville Redenbacher, hybrid popcorn developer[55]

- Henry P. Rusk, dean of the Department of Agriculture at the University of Illinois

- Jeff Samardzija, professional baseball player in MLB[56]

- Carly Schroeder, actress[57]

- Walter Wangerin, Jr., author and professor at Valparaiso University[58]

- R. Harold Zook, architect[59]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Valparaiso, Indiana

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ One of the earliest Authentic histories of Porter County, Indiana, From 1832 to 1876; Deborah H. Shults-Gay; ca 1917

- ^ Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History; Helen Hornbeck Tanner; University of Oklahoma Press; Norman, Oklahoma, 1987; map 25

- ^ "History of Valparaiso". Valparaiso, Indiana. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Baker, Ronald L.; Marvin Carmony (1995). Indiana Place Names. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0-253-28340-X.

- ^ a b Mitchell, David (June 30, 2003). "A struggled balance of hope and fear". The Times of Northwest Indiana. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

More than 30 years ago, Barbara Frazier-Cotton, a single, black mother raising her six children in Chicago's public housing projects, brought her family to Valparaiso where they became the first to breach the city's color barrier. The house butted against a thick wooded area at the end of a short, curved drive. Officials refused to hook up municipal water, even though they lived within city limits. The family relied on well water. Thinking back, Walt Reiner to this day says he wouldn't wish on an enemy what Frazier-Cotton went through that first year in Valparaiso. On occasion, Frazier-Cotton also wonders aloud why she didn't just pack up and leave. More moments than she'd like to remember forced her to question whether she made the right decision. The phone rang often in the middle of the night. "Go home," the voice on the other end would say. "You don't belong here." Strange cars rolled down the driveway late at night. "I was afraid to call the police," she says. "They said earlier they wouldn't come." One summer night, she awoke, sat up in bed and looked straight at a man staring at her through an open window. The windows remained closed for a long time after that. People gawked at her in stores or on the street. A stranger once handed her a business card that read, "Keep Valparaiso Clean" on one side and "KKK" on the other. Crosses were burned on her lawn." For the most part, the schools and churches stood strong and supportive. Some Valparaiso educators even took the opportunity to have Frazier-Cotton speak to their students, offering them exposure to an otherwise inaccessible perspective on cultural diversity. Many Valparaiso University students befriended the family, regardless of race. Others in the city also accepted Frazier-Cotton into the community. Still, her children's names would often be the first mentioned when something turned up missing or vandalized.

- ^ Loewen, James W. (2005). Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. New York: New Press. pp. 67, 199, 200, 413. ISBN 0743294483.

I identified a total of 231 Indiana towns as all-white. I was able to get information as to the racial policies of 95, and of those, I confirmed all 95 as sundown towns. In Indiana, I have yet to uncover any overwhelmingly white town that on-site research failed to confirm as a sundown town. Ninety-five out of 95 is an astounding proportion; statistical analysis shows that it is quite likely that 90 to 100% of all 231 were sundown towns. They ranged from tiny hamlets to cities in the 10,000-50,000 population range, including Huntington (former vice president Dan Quayle's hometown) and Valparaiso (home of Valparaiso University).

- ^ Taylor, Stephen J. (January 6, 2016). "Ku Klux U: How the Klan Almost Bought a University". Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana's Digital Newspaper Program. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Mitchell, David (June 30, 2003). "A struggled balance of hope and fear – continued". The Times of Northwest Indiana. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

<When her stepson showed up at her front door, the previous winter's tragic events at the university were quickly becoming a distant memory. Horace Smith Jr. arrived unannounced at her Cedar Lane house in early August of 1980, looking for a little space and time to straighten some things out. [...] His decision to come to Valparaiso proved costly. In the early morning hours of Aug. 22, 1980, two brothers on their way to go squirrel hunting found Smith dying in a ditch along U.S. 30, just west of Ind. 51. "He was unable to talk and was gasping for air. They tried to get him to state what happened, but he was incoherent," said First Sgt. Glen Edmondson of the Indiana State Police, who reviewed the file years later. Trooper Richard Bonesteel arrived just before 4 a.m. Smith was dead. Because Smith was black, officers assumed he was from Lake County and notified Gary police first. The initial report said Smith was either pushed from a moving vehicle or struck by a car while walking along the side of the road. The Lake County Coroner's office ruled out suicide, but listed the cause of death as undetermined. The case remains unsolved, a dense file in the state police's Cold Case division. Many specifics about the case are restricted because it technically is still under investigation. And family members are still reluctant to rehash details. Smith's body had cuts and bruises, but the only bone fracture was to the lower, rear portion of his skull, indicating someone probably hit him in the back of the head. Smith had no other broken bones, making it difficult to imagine he was hit by a car. Edmondson, filtering through decades old documents, says there were indications race played a role. "I think there's some of those issues that go on in these arguments because some of the people it makes mention of are black and some are white," Edmondson says. Betty Ballard, Frazier-Cotton's long-time friend, says Frazier-Cotton came to her house shortly after Smith's death, frightened because she had received a phone call from someone who may have had a hand in her stepson's death. "They called her and told her they were going to kill her," Ballard says. "She called me and told me, 'Betty, we've got to leave. They're going to kill us all.'" The day after Frazier-Cotton identified her stepson for police, the Vidette-Messenger, the local newspaper, ran two related front page stories. A small item explained how police had identified Horace Smith, a relative of Valparaiso's first black family, as the youth found dead along U.S. 30 days earlier. The main story described a cross burning on the lawn outside of the newspaper office. Two Ku Klux Klan business cards at the base of the cross read, "Racial purity is America's security." "The Klan is watching you" stickers were pasted on a van and a car in the building's parking lot. Ultimately, Smith's death proved to be Frazier-Cotton's breaking point. It was time to leave.

- ^ "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ "Station: VALPARAISO PORTER CO MUNI AP, IN US USW00004846". Summary of Monthly Normals for 1991-2020. National Oceanic and atmospheric administration. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ "Station: VALPARAISO WTR WKS, IN US USC00128999". ncei.noaa.gov. National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Valparaiso, IN". The Weather Channel.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Home - Chicago Street Theatre". chicagostreet.org. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ "Valparaiso Theatrical Company - The Theater That Cares". valparaisotheatricalcompany.org. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ "Task Force Tips - Task Force Tips-Museum and Tours". Tft.com. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "Porter County Museum". Pocomuse.org. May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "Locations". Porter County Public Library System. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Neeley, George E.; City of Valparaiso, A Pictorial History; G. Bradley Publishing, Inc.; St. Louis, Missouri; 1989

- ^ Your Guide to Summer Fun! Indiana Dunes, The Casual Coast; Porter County Convention and Recreation and Visitors Commission, 2005

- ^ joseph.pete@nwi.com, 219-933-3316, Joseph S. Pete (May 19, 2024). "Long a hazard to cars, Rock Island has become the talk of Valparaiso". nwitimes.com. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Tower Park". City of Valparaiso. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Northwest Indiana Bike Map, Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission, Spring 2008

- ^ Sesquicentennial, The way We Were in 1986, Sesquicentennial Board; Porter County, Indiana; 1986

- ^ McCollum, Carmen (March 8, 2016). "Future of Purdue campus in Valparaiso uncertain". nwi.com. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ "Porter County News". nwitimes.com. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ "Porter County". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Indiana Transportation Map (PDF) (Map) (2011–12 ed.). Cartography by INDOT. Indiana Department of Transportation. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ Indiana Railroad Map (PDF) (Map). Cartography by INDOT. Indiana Department of Transportation. August 23, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ "Newton Arvin". Smithipedia. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "John L. Bascom". legis.iowa.gov. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Beulah Bondi". TURNER ENTERTAINMENT NETWORKS, INC. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Kevin Brown". Pro-Baseball Reference . Com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Mark N. Brown". jsc.nasa.gov. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Bryce Drew". Pro-Basketball Reference . Com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Whatever Happened To?: Here are the Next Chapters of Notable Northwest Indiana TV Reality Stars". The Chicago Tribune. July 10, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Chris Funk". nwitimes.com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Biographies of U.S. Astronauts". Spacefacts. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ "Zach Holmes Zerocool trading card". Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ "Robbie Hummel". ESPN Internet Ventures. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Samuel Austin Kendall". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Introducing Mike Kellogg". CPCI.org. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ "Valpo's Heather Kuzmich a TV 'Top Model'". The Times of Northwest Indiana. October 28, 2007. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Earl F. Landgrebe". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form; US Dept of the Interior, National Park Service; Dr. David J. Loring Residence and Clinic; Bertha Stalbaum & Alice Vietzke; Valparaiso Woman’s Club; Valparaiso, Indiana, June 11, 1984

- ^ David E. Lilienthal. David E. Lilienthal: The Journey of an American Liberal. 1996. ISBN 9780870499401. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ Glenesk, Matthew (May 11, 2018). "How MLB players from Indiana are faring so far in 2018". The Indianapolis Star.

- ^ "Sean Manaea Stats". Baseball-Reference.com.

Born: February 1, 1992 (Age: 28-110d) in Valparaiso, IN

- ^ "Orville Redenbacher". nwitimes.com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Jeff Samardzija". Pro-Baseball Reference . Com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Carly Schroeder". nwitimes.com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Walter Wangerin, Jr". Valparaiso University. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "Historical society opens Zook Studio to public". Chicago Tribune. October 21, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

External links

edit- Official website

- Greater Valparaiso Chamber of Commerce Archived 2006-04-27 at the Wayback Machine