The silver chimaera (Chimaera phantasma), or ginzame, is a species of holocephalan in the family Chimaeridae. They are found in the deep sea along the coast of East Asia, from Japan to Indonesia. They are chondrichthyans, closely related to sharks and rays, which means that they have a fully cartilaginous skeleton with no true bones.

| Silver chimaera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Holocephali |

| Order: | Chimaeriformes |

| Family: | Chimaeridae |

| Genus: | Chimaera |

| Species: | C. phantasma

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chimaera phantasma D. S. Jordan & Snyder, 1900

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Chimaera pseudomonstrosaFang & Wang, 1932 | |

Silver chimaeras have stout, triangular snouts and long tapered bodies ending in thin, whip-like tails. They grow to a maximum length of 110 cm (43.3 in) for both males and females.[1] They have two dorsal fins. The anterior dorsal fin is tall, narrow, and triangular with a single hard spine at the front. The posterior dorsal fin is short and elongated and lacks spines.[2] Silver chimaera pectoral fins are broad and triangular and span about a third of the chimaera’s body length.[2][3] Silver chimaeras have exceptionally long tails, with the length of the tail (measured from the end of the anal fin to the tip of the tail) being about a third of the chimaera’s total length.[3] The caudal fin is divided into two small, symmetrical lobes above and below the base of the tail. Silver chimaeras are pale and silvery, with dark lateral stripes.[2] They have unique dentition compared to other chondrichthyans. Silver chimaeras have flat tooth plates which grow continuously, like rodent teeth. There are two symmetrical pairs of tooth plates in the top jaw and one pair in the bottom jaw.[2][4]

Silver chimaeras are benthic predators, meaning that they spend most of their time near the seafloor, hunting for prey hiding in sand or mud. They primarily eat crustaceans and shellfish, using their tooth plates to crush their hard shells.[5]

Silver chimaeras reproduce by internal fertilization, and lay eggs in egg cases. Females may lay one or two eggs at a time, which take around eight months to hatch.[2]

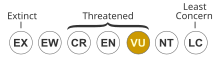

While there is very lacking data on the population size and distribution of silver chimaeras, they are considered Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List. This is based on known overfishing threats and population trends for chimaeras and chondrichthyans as a whole.[1]

Taxonomy

editSilver chimaeras fall into the family Chimaeridae, the short-nosed chimaeras, in order Chimaeriformes. This order includes two other families, Rhinochimaeridae (the long-nosed chimaeras) and Callorhinchidae (the elephantfish). Chimaeriformes is the only extant order in the subclass Holocephali, within class Chondrichthyes.[5]

Holocephali diverged from their nearest relatives, Elasmobranchii (sharks and rays), about 300 million years ago, in the Paleozoic Era.[5]

Distribution and habitat

editSilver chimaeras are found along the continental shelf and upper slope of the East China Sea. They have been found at depths between 20-960 m (65.6-3149.6 ft), but they are most common around depths of 500 m (1640 ft). They live off the coast of East Asia, from the north tip of Japan to the north of Indonesia.[1][3]

Anatomy and appearance

editThe silver chimaera grows to a maximum length of 110 cm (43.3 in) in both males and females, and they reach sexual maturity at lengths greater than 65 cm (25.6 in).[1] Their heads are stout and triangular, and their mouths are located on the bottom of their heads, facing the seafloor.[2] Silver chimaeras have flat tooth plates which grow continuously, like rodent teeth. There are two pairs of tooth plates in the top jaw and one pair in the bottom jaw.[4] A silver chimaera’s pectoral fins are broad and triangular. These fins are quite flexible, compared to other chondrichthyans, and they are the primary fins used for generating power for swimming. They have both an anterior and posterior dorsal fin. The anterior dorsal fin is tall and triangular, with a single venomous spine at the front of the fin. The posterior dorsal fin is very long and flat, and spans a large portion of the chimaera’s body, from the middle of the torso to the base of the tail. Silver chimaeras have long, whip-like tails, which have two symmetrical caudal fin lobes above and below the base of the tail. A silver chimaera is primarily pale silver in coloration, with dark stripes running down the sides of the body. Silver chimaeras have four gill openings covered by a single cartilaginous operculum. They lack spiracles, which are common in many other chondrichthyans.[2]

Male silver chimaeras, like all chondrichthyans, have claspers near their pelvis to assist in mating. However, chimaeras have both the typical pair of pelvic claspers and a single frontal clasper on top of their heads. The pelvic claspers are trifurcated, branching into three forks, and lack hooks that are present on elasmobranch claspers.[3]

Tooth Plates

editThe tooth plates are unique organs, found only in holocephalans and lungfish. Silver chimaeras have three pairs: the vomerine and palatine pairs in the top jaw, and the lower pair in the bottom jaw. These tooth plates are used to crush the hard shells of the mollusks and crustaceans that silver chimaeras eat.[4]

Chimaera tooth plates are composed of three different tissue types. Osteodentin is only lightly mineralized, and therefore relatively soft. It makes up the majority of the tooth plate but acts largely as a structural component. Pleromin is hypermineralized and provides most of the strength of the tooth plate. Outer dentin covers the entire tooth plate, acting as a protective layer for the tooth plate. It has a three-layer structure, consisting of a highly mineralized core layer sandwiched by less mineralized inner and outer layers. Osteodentin forms the core of the tooth plate and is covered above and below by pleromin.[4]

There are two forms of pleromin, vascular and compact. Vascular pleromin surrounds and protects vascular canals, which provide blood and nutrients to the growing tooth. Vascular pleromin is quite porous in the immature region of the tooth plate (where the tooth plate is actively growing), but it becomes denser as it moves to the mature region of the tooth plate. Compact pleromin forms in lines of oval shapes at the biting edge of the tooth plate, where it provides additional strength and durability to the tooth plate. Vascular pleromin is always found between the osteodentin and the inside of the mouth: above the osteodentin in the top jaw and below it in the bottom jaw. Compact pleromin is found between the osteodentin and the outside of the mouth, opposite from the vascular pleromin.[7]

Ecology and behavior

editSilver chimaeras are deep benthic and neritic predators, meaning that they primarily feed along the deep seafloor and the continental shelf. Their primary prey items are mollusks and crustaceans, though they also eat soft-bodied prey like jellyfish and sea squirts. Silver chimaeras are prey for sharks and seals and are also occasionally eaten by other chimaeras.[5]

Silver chimaeras primarily hunt using electroreceptive organs called ampullae of Lorenzini, which can detect small electrical fields created by living creatures. These ampullae are mostly found on the snout and are particularly concentrated on the underside of the head, near the mouth. Silver chimaeras also have a well-developed sense of smell, and they have adapted to have naso-oral grooves on their skin connecting the nostrils to the mouth. This allows a near constant flow of water to the olfactory system, allowing the silver chimaera to constantly smell its surroundings.[5]

Diet

editSilver chimaeras primarily prey on benthic invertebrates, such as crustaceans, echinoderms, and mollusks. Chimaeras use their electroreception to detect these organisms hiding under sand and rocks, then crush through their tough shells using their tooth plates. Silver chimaeras also consume soft-bodied prey, such as anemones, tunicates, jellyfish, polychaetes, and salps. All of these prey items are rather slow-moving or entirely sessile, indicating that silver chimaeras are not fast hunters but rather slow foragers.[5]

Reproduction

editSilver chimaeras have internal fertilization and are oviparous, meaning that they lay eggs rather than giving birth to live young.[5] Like most chondrichthyans, these eggs are protected by an egg case, a tough pouch that protects the egg. The egg cases of silver chimaeras are bottle-shaped, with long necks and a pair of fins on its side. This shape may be useful in deterring predators or maintaining the egg’s position on the seafloor. Female silver chimaeras lay only a single egg in each egg case, but they may lay one or two egg cases at a time. The eggs hatch after about 8 months.[2] Silver chimaeras have an average generation length of 18.6 years.[1]

Mating season lasts about half of the year, from fall to spring, peaking in winter.[8] Silver chimaera males have claspers to assist in mating. All chondrichthyans have a pair of claspers near their pelvis, but chimaeras, uniquely, also have a single frontal clasper on the top of their head. The pelvic claspers are trifurcated, meaning that they split into three forks. Unlike the pelvic claspers of elasmobranchs, silver chimaera claspers lack dermal hooklets, the sharp hooks that allow the claspers to hold onto a female while mating.[3]

Parasites

editSeveral new parasite species were first found on silver chimaeras. The trematode Multicalyx elegans was first found parasitizing the gallbladder of a silver chimaera,[9] and the monogenean Callorhynchocotyle sagamiensis was found parasitizing the gill filaments of silver chimaeras. C. sagamiensis was found parasitizing approximately 65% of silver chimaeras.[10]

Relationships with humans

editSilver chimaeras are found in areas of heavy commercial fishing, but they are not a target of commercial fishing. Rather, silver chimaeras are common bycatch and often discarded upon capture. Occasionally, if chimaeras are caught in large enough quantities, they will be brought ashore and consumed.[1]

Conservation status

editThe IUCN Red List labels the silver chimaera as Vulnerable. While there is no data for the actual population size and distribution of silver chimaeras, their range includes areas that face extensive pressures from commercial fishing. By extrapolating from population data of all local chondrichthyans, researchers estimated that the silver chimaera population had declined about 30-49% in the last 50 years.[1]

Silver chimaeras, like other long-lived chondrichthyans, are particularly at-risk due to their long generation times, which mean that they are slower to adapt to changing ecological pressures. Currently, overfishing poses a great threat to silver chimaera populations. While they are not targets of commercial fishing, silver chimaeras are common bycatch, especially when trawl fishing. Fortunately, trawling has become significantly less common in recent decades, due in part to regulations to protect marine environments.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Finucci, B; Sho, T; Yasuko, S; Atsuko, Y (2020). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Chimaera phantasma". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific. 3: Batoid fishes, chimaeras and bony fishes part 1 (Elopidae to Linophrynidae). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1999. ISBN 978-92-5-104302-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Malagrino, Giovanni; Takemura, Akira; Mizue, Kazuhiro (February 1977). "Studies on Holocephali―I On the morphology and ecology of Chimaera phantasma, and male reproductive organs". 長崎大学水産学部研究報告 (in Japanese). 42: 11–19.

- ^ a b c d e Iijima, Mayumi; Okumura, Taiga; Kogure, Toshihiro; Suzuki, Michio (December 2021). "Microstructure and mineral components of the outer dentin of Chimaera phantasma tooth plates". The Anatomical Record. 304 (12): 2865–2878. doi:10.1002/ar.24606. ISSN 1932-8486.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lisney, Thomas J. (December 2010). "A review of the sensory biology of chimaeroid fishes (Chondrichthyes; Holocephali)". Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 20 (4): 571–590. doi:10.1007/s11160-010-9162-x. ISSN 0960-3166.

- ^ "Chimaera phantasma". shark-references.com. Retrieved 2024-11-09.

- ^ a b Iijima, Mayumi; Ishiyama, Mikio (2020-10-29). "A unique mineralization mode of hypermineralized pleromin in the tooth plate of Chimaera phantasma contributes to its microhardness". Scientific Reports. 10 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-020-75545-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7596707. PMID 33122684.

- ^ Malagrino, Giovanni; Takemura, Akira; Mizue, Kazuhiro (August 1981). "Studies on Holocephali―II On the Reproduction of Chimaera phantasma JORDAN et SNYDER Caught in the Coastal Waters of Nagasaki". 長崎大学水産学部研究報告 (in Japanese). 51: 1–7.

- ^ Machida, M; Araki, J (1992). "Three aspridogastrean trematodes from marine fishes of Japan". Bulletin of the National Science Museum. A, Zoology. 18 (2).

- ^ Kitamura, Akiko; Ogawa, Kazuo; Taniuchi, Toru; Hirose, Hitomi (2006-09-08). "Two new species of hexabothriid monogeneans from the ginzame Chimaera phantasma and shortspine spurdog Squalus mitsukurii". Systematic Parasitology. 65 (2): 151–159. doi:10.1007/s11230-006-9046-6. ISSN 0165-5752.