Chadderton is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham, Greater Manchester, England, on the River Irk and Rochdale Canal. It is located in the foothills of the Pennines, 1 mile (1.6 km) west of Oldham, 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Rochdale and 6 miles (9.7 km) north-east of Manchester.

| Chadderton | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

| |

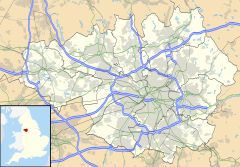

Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Population | 34,818 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 6,900/sq mi (2,700/km2) |

| OS grid reference | SD905055 |

| • London | 165 mi (266 km) SSE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Areas of the town | |

| Post town | OLDHAM |

| Postcode district | OL1, OL9 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Historically part of Lancashire, Chadderton's early history is marked by its status as a manorial township, with its own lords, who included the Asshetons, Chethams, Radclyffes and Traffords. Chadderton in the Middle Ages was chiefly distinguished by its two mansions, Foxdenton Hall and Chadderton Hall, and by the prestigious families who occupied them. Farming was the main industry of the area, with locals supplementing their incomes by hand-loom woollen weaving in the domestic system.

Chadderton's urbanisation and expansion coincided largely with developments in textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution and the Victorian era. A late-19th century factory-building boom transformed Chadderton from a rural township into a major mill town and the second most populous urban district in the United Kingdom. More than 50 cotton mills had been built in Chadderton by 1914.

Although Chadderton's industries declined in the mid-20th century, the town continued to grow as a result of suburbanisation and urban renewal. The legacy of the town's industrial past remains visible in its landscape of red-brick cotton mills, now used as warehouses or distribution centres. Some of these are listed buildings because of their architectural, historical and cultural significance.[1][2]

History

editToponymy

editThe name Chadderton derives from Caderton, which is believed to be a combination of the Brythonic word Cader or Cater (modern Welsh: Caer), indicating a fortified place amongst the hills, or the cadeir, "chair, throne",[3] and the Old English suffix -ton meaning a settlement.[4][5][6] The University of Nottingham's Institute for Name-Studies has offered a similar suggestion, that the name Chadderton means "farm or settlement at the hill called Cadeir".[7] This name is believed to date from the 7th century, when Angles colonised the region following the Battle of Chester.[8] It has been suggested that the Anglian settlers found a few Brythonic Celts already inhabiting what is now called Chadderton, and borrowed their name for the hill, "Chadder", adding their own word for a settlement to the end.[9] Archaic spellings include Chaderthon, Chaderton, Chaterton and Chatherton.[10] The first known written record of the name Chadderton is in a legal document relating to land tenure, in about 1220.[5]

Early history

editThe study of place names in Chadderton suggests that the ancient Britons once inhabited the area.[9] Remains of Roman roads have been discovered running through the town,[4][10] and the local road name Streetbridge suggests that the Romans once marched along it on a path which may have led to Blackstone Edge.[5][6] Relics found at a tumulus in Chadderton Fold date from the Early Middle Ages, probably from the early period of Anglo-Saxon England,[5][10] when Angles settled in the area and Chadderton emerged as a manor of the hundred of Salford.

Chadderton is not recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. Its first appearance in a written record is in a legal document from around 1220, which states that Robert, Rector of Prestwich, gave land to Richard, son of Gilbert, in exchange for an annual fee of one silver penny.[5] Following the Norman conquest, Chadderton was made a constituent manor of the wider Royal Estate of Tottington, an extensive fee held by the Norman overlord, Roger de Montbegon.[4][11] Taxation and governance continued on this basis throughout the Middle Ages, with the Barons Montbegon of Hornby Castle holding the estate, until it passed to the Barons Lacy of Clitheroe Castle, and then onto local families.[4] In about 1235, the sub-manor of Chadderton and Foxdenton passed from Richard de Trafford of Trafford Park to Geoffrey de Trafford, who adopted the surname of Chadderton, thus founding the Chadderton family.[6] During the High Middle Ages, pieces of land in Chadderton were granted to religious orders and institutions, including Cockersand Abbey and the Knights Hospitaller.[5]

The manorial system was strong in Chadderton, and this lent distinction to the township,[4] in a region which otherwise had weak local lordship.[12] Throughout the Middle Ages, the manor of Chadderton constituted a township, centred on the hill by the banks of the River Irk, known as Chadderton Fold.[4] The fold consisted of a cluster of cottages centred on Chadderton Hall manor house, and a water-powered corn mill.[4] Chadderton Hall was owned and occupied by the de Chaddertons. Geoffrey de Chadderton became the Lord of the Manor of Tottington in the 13th century.[13][14] The de Chaddertons' involvement in regional and national affairs gave prestige to what was otherwise an obscure and rural township. William Chaderton was Bishop of Chester from 1579 to 1595 and held distinguished academic posts such as Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity.[14][15] Laurence Chaderton was the first Master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge and among the first translators of the King James Version of the Bible.[14] Tottington was dissolved in the mid-15th century and there came a succession of distinguished families, each headed by an esquire with links to the monarchs of England. The Radclyffe, Assheton, and Horton families provided six High Sheriffs of Lancashire and a Governor of the Isle of Man.[14]

Apart from the dignitaries who lived in Chadderton's manor houses, Chadderton's population during the Middle Ages comprised a small community of retainers, most of whom were occupied in farming, either growing and milling of grain and cereal or raising cattle, sheep, pigs and domestic fowl.[6] Workers supplemented their incomes by hand-loom spinning and weaving of wool at home.[4][6] The community was ravaged by an outbreak of the Black Death in 1646.[16]

Textiles and the Industrial Revolution

editUntil the mid-18th century, the region in and around Chadderton was dominated by dispersed agricultural settlements.[18] During this period the population was fewer than 1,000, broadly consisting of farmers who were involved with pasture, but who supplemented their incomes by working in cottage industries, particularly fustian and silk weaving.[6][19] A fulling mill at Chadderton by the River Irk was recorded during the Elizabethan era,[19] and during the Early Modern period the weavers of Chadderton had been using spinning wheels in makeshift weavers' cottages to produce woollens. Primitive early 18th-century industrialisation developed slowly in Chadderton.[6] However, as the demand for cotton goods increased and the technology of cotton-spinning machinery improved during the mid-18th century, the need for larger structures to house bigger, better, and more efficient equipment became apparent. A water-powered cotton mill was built at Chadderton's Stock Brook in 1776.[13][20][21] The damp climate below the South Pennines provided ideal conditions for textile production to be carried out without the thread drying and breaking, and newly developed 19th-century mechanisation optimised cotton spinning for industrial-scale manufacture of yarn and fabric for the global market. As the Industrial Revolution advanced, socioeconomic conditions in the region contributed to Chadderton adopting cotton spinning in the factory system, which became the dominant source of employment in the locality.[19] The construction of multi-storey steam powered mills followed, which initiated a process of urbanisation and cultural transformation in the region; the population increasingly moved away from farming and domestic weaving in favour of the mechanised production of cotton goods.[12]

During this early period of change, Chadderton's parliamentary representation was limited to two Members of Parliament for Lancashire. Nationally, the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 had resulted in periods of famine and unemployment for textile workers.[22] Nevertheless, despite years of distress and unrest, major disturbances of machine-breaking did not occur until 1826.[23] By the beginning of 1819 the pressure generated by poor economic conditions, coupled with the lack of suffrage in Northern England, had enhanced the appeal of political Radicalism in the region.[22] The Manchester Patriotic Union, a group agitating for parliamentary reform, began to organise a mass public demonstration in Manchester to demand the reform of parliamentary representation. Organised preparations took place, and a spy reported that in neighbouring Thornham, "seven hundred men drilled ... as well as any army regiment would".[24] A few days later, on 3 August, a royal proclamation forbidding the practice of drilling was posted in Manchester.[25] On 16 August 1819, Chadderton (like its neighbours) sent a contingent of its townsfolk to Manchester to join the mass political demonstration now known as the Peterloo Massacre (owing to the 15 deaths and 400–700 injuries which followed).[17][26] Two of the 15 deceased were from the area: John Ashton of Cowhill and Thomas Buckley of Baretrees.[27]

New markets in Europe and South America increased the demand for Britain's cheap cotton goods. Supplies of raw cotton were exported from plantations in the United States to Manchester.[28][29] From the markets in Manchester, mill owners from Chadderton and neighbouring towns bought their cotton to be processed into yarn and cloth. Supplies were cut during the Lancashire Cotton Famine of 1861–65 as a result of the American Civil War, leading to the formation of the Chadderton Local Board of Health in 1873, whose purpose was to ensure social security and maintain hygiene and sanitation in the locality following the crisis.[30] Despite a brief economic depression, the urban growth of Chadderton accelerated after the famine. The profitability of factory based cotton spinning meant that much of Chadderton's plentiful cheap open land, used for farming since antiquity, vanished under distinctive rectangular multi-storey brick-built factories—35 by 1891.[19] Chadderton's former villages and hamlets agglomerated as a mill town around these factories and a network of newly created roads, canals and railways.[20][31][32] The Chadderton landscape was "dominated by mill chimneys, many with the mill name picked out in white brick".[33] Neighbouring Oldham (which by the 1870s had emerged as the largest and most productive mill town in the world)[18][34] encroached upon Chadderton's eastern boundary, urbanising the town and surrounds,[35] and forming a continuous urban cotton-spinning district with Royton, Lees and Shaw and Crompton—the Oldham parliamentary constituency—which at its peak was responsible for 13 per cent of the world's cotton production.[36] These Victorian era developments shifted the commercial focus away from Chadderton Fold to the major arterial Middleton Road, by Chadderton's eastern boundary with Oldham.[13][31] Sixty cotton mills were constructed in Chadderton between 1778 and 1926,[19] and 6,000 people, a quarter of Chadderton's population, worked in these factories by the beginning of the 20th century.[37] Industries ancillary to cotton spinning, such as engineering, coal mining, bleaching and dyeing became established during this period, meaning the rest of Chadderton's population were otherwise involved in the sector. Philip Stott was a Chadderton-born architect, civil engineer and surveyor of cotton mills. Stott's mills in Chadderton were some of the largest to be built in the United Kingdom, multiplying the town's industrial capacity and in turn increasing its population and productivity.[38]

The boomtown of Chadderton reached its industrial zenith in the 1910s, with over 50 cotton mills within the town limits.[20] A social consequence of this industrial growth was a densely populated metropolitan landscape, home to an extensive and enlarged working class community living in an urban sprawl of low quality terraced houses.[39] However, Chadderton developed an abundance of civic institutions including public street lighting, Carnegie library, public swimming baths and council with its own town hall. The development of the town meant that the district council made initial steps to petition the Crown for honorific borough status for Chadderton in the 1930s.[13][30] However, the Great Depression, and the First and Second World Wars each contributed to periods of economic decline. As imports of cheaper foreign yarns and textile goods increased during the mid-20th century, Chadderton's textile sector declined to a halt; cotton spinning reduced dramatically in the 1960s and 1970s and by 1997 only two mills were operational.[20] In spite of efforts to increase the efficiency and competitiveness of its production, the last cotton was spun in the town in 1998.[17][40] Many of the redundant mills have now been demolished. Non-textile based industries continued on throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century, particularly in the form of aircraft and chemical manufacture at plants in south Chadderton and Foxdenton respectively.[6]

Post-industrial history

editDuring the second half of the 20th century, Chadderton experienced accelerated deindustrialisation along with economic decline.[20] Large areas of Victorian and Edwardian era terraced housing were identified as unsuited for modern needs, and were subsequently demolished.[41] However, the town's population continued to grow as a result of urban renewal and modern suburban housing developments.[6][42] During the 1970s and 1980s, redevelopment in the form of new shopping, health and leisure facilities contributed to the growth and renewal of Chadderton.[6][43] In 1990, the new Firwood Park, on the west side of Chadderton, was said to be the largest private housing estate in Europe.[43][44] Chadderton continued to be a regional hub for the secondary sector of the economy into the 21st century through BAE Systems and Zetex Semiconductors, though BAE Chadderton closed in March 2012.[40][45] Other major employers include the Stationery Office and Trinity Mirror.[6][40]

Governance

editLying within the historic county boundaries of Lancashire since the early 12th century, the boundaries of Chadderton have varied from time to time.[10] Chadderton anciently formed part of the hundred of Salford for civil jurisdiction, but for manorial government, Chadderton was a constituent manor of the Fee of Tottington, whose overlords were the de Lacys, Barons of Clitheroe Castle.[11] The de Chaddertons, Lords of the Manor of Chadderton, were accustomed to pay tax to the overlords until the division of Tottington.[11][48] In 1507, two constables were appointed to uphold law and order in Chadderton.[49] Following a court case, in 1713 it was agreed that 20 acres (8 ha) of Northmoor be within Chadderton with the rest belonging to Oldham.[50]

Following the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, Chadderton formed part of the Oldham Poor Law Union, an inter-parish unit established to provide social security. Chadderton's first local authority was a local board of health established in 1873; Chadderton Local Board of Health was a regulatory body responsible for standards of hygiene and sanitation in the township. Following the Local Government Act 1894, the area of the local board became the Chadderton Urban District, a local government district within the administrative county of Lancashire.[51] The urban district council, comprising 18 members, would later be based out of Chadderton Town Hall, a purpose built municipal building opened in 1913.[47] In 1933, there were exchanges of land with the neighbouring Municipal Borough of Middleton and City of Manchester.[51]

Chadderton was the second most populous urban district in the United Kingdom by the 1930s, and the district council took initial steps to obtain municipal borough status, but this was not achieved. In 1926 and 1931, two Oldham Extension Bills for the County Borough of Oldham to amalgamate with Chadderton Urban District were rejected by the House of Lords, following objections from neighbouring councils.[30][52] A twinning arrangement was made in 1966 by Chadderton Urban District Council with Geesthacht, West Germany.[53] Under the Local Government Act 1972, the Chadderton Urban District was abolished, and Chadderton has, since 1 April 1974, formed an unparished area of the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham, a local government district of the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.[5][13][51][54] Chadderton has three of the twenty wards of the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham: Chadderton North, Chadderton Central and Chadderton South.,[55] with some small peripheral areas lying in the neighbouring wards of Royton North, Coldhurst, Hollinwood, Werneth and Failsworth East.[56]

In terms of parliamentary representation, Chadderton after the Reform Act 1832 was represented as part of the Oldham parliamentary borough constituency, of which the first Members of Parliaments (MPs) were the radicals William Cobbett and John Fielden.[57] Winston Churchill was the MP between 1900 and 1906.[58] Constituency boundaries changed during the 20th century, and Chadderton has lain within the constituencies of Middleton and Prestwich (1918–1950) and Oldham West (1950–1997). Since 1997, Chadderton has lain within Oldham West and Royton. It is represented in the House of Commons by Jim McMahon, a member of the Labour Party.

Geography

editAt 53°32′46″N 2°8′33″W / 53.54611°N 2.14250°W (53.5462°, −2.1426°), and 165 miles (266 km) north-northwest of central London, Chadderton lies at the foothills of the Pennines, 2.7 miles (4.3 km) east-southeast of Middleton, and 1.1 miles (1.8 km) west of Oldham. It is in the northeast part of the Greater Manchester Urban Area,[59][60] the UK's third largest conurbation, on undulating land rising from 300 feet (91 m) above sea level in the west to 450 feet (137 m) in the east. Chadderton Heights, on the hillier northern edge of the town, is its highest point at 509 feet (155 m).[10]

The climate in the area, like most of northwest Europe,[61] is maritime temperate, with significant precipitation throughout the year, averaging 1047 mm annually.[62] The average annual temperature is 9.7 °C.[62]

Chadderton's modern commercial centre lies close to the boundary with Oldham; the expansion of Oldham in the mid-19th century caused urbanisation along the eastern boundary of Chadderton, which spread outwards into the rest of the township.[35] Continued growth in the late-19th and early-20th centuries gave rise to a densely populated, industrial landscape of factories and rows of terraced housing, typical of mill towns in Northern England.[6][10] There is a mixture of high-density urban areas, suburbs and semi-rural locations in Chadderton, but overwhelmingly the land use in the town is urban. The soils of Chadderton are sand based, with subsoils of clay and gravel.[10]

Chadderton's built environment is distinguished by its former textile factories: "The huge flat-topped brick mills with their square towers and their tall circular chimneys dwarf all other buildings."[63] Rows of early-20th century terraced housing built to house Chadderton's factory workers are a common type of housing stock throughout the town; narrow streets pass through these older housing areas.[6]

Chadderton is contiguous with other settlements on all sides, including a shared boundary with the city of Manchester to the southwest.[4]

Localities within Chadderton include Baretrees, Block Lane, Busk, Butler Green, Chadderton Fold, Chadderton Park, Coalshaw Green, Cowhill, Greengate, Firwood Park, Foxdenton, Healds Green, Middleton Junction, Mills Hill, Nimble Nook, Nordens, Stock Brook, Whitegate and White Moss.[10][13][17][64] Chadderton Fold, the former centrepoint of Chadderton, lies on the banks of the River Irk, 1.3 miles (2 km) north-northwest of Chadderton's modern commercial centre. Hollinwood, in pre-industrial times, was a moor or common of Chadderton, but was largely incorporated into neighbouring Oldham following a court case in 1713.[10] In the mid-18th century a village emerged at Hollinwood along the common border of Oldham and Chadderton, and there were further exchanges of land at Hollinwood between Oldham Borough and Chadderton township in 1880.[65] "Chadderton (Detached)" was, as its name implies, a detached area or exclave of Chadderton. Lying under Copster Hill in Oldham and including the area now known as Garden Suburb, its area was absorbed into neighbouring Oldham in 1880.[66][67]

Demography

editThis article needs to be updated. (January 2014) |

| Chadderton compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK census | Chadderton[68] | Oldham (borough)[69] | England |

| Total population | 33,001 | 217,273 | 49,138,831 |

| White | 94.4% | 86.1% | 90.9% |

| Asian | 3.8% | 11.9% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.5% | 0.6% | 2.3% |

According to the Office for National Statistics, at the time of the United Kingdom Census 2001, Chadderton (urban-core and sub-area) had a total resident population of 33,001.[70] The population density was 8,669 inhabitants per square mile (3,347/km2), with a 100 to 95.4 female-to-male ratio.[71] Of those over 16 years old, 27.2 per cent were single (never married) 44.5 per cent married, and 8.5 per cent divorced.[72] Chadderton's 13,698 households included 28.8 per cent one-person, 38.7 per cent married couples living together, 8.9 per cent co-habiting couples, and 10.3 per cent single parents with their children.[73] Of those aged 16–74, 35.6 per cent had no academic qualifications.[74]

At the 2001 UK census, 81.1 per cent of Chadderton's residents reported themselves as being Christian, 3.2 per cent Muslim, 0.5 per cent Hindu, 0.1 per cent Buddhist, and 0.1 per cent Sikh. The census recorded 8.7 per cent as having no religion, 0.1 per cent had an alternative religion and 6.3 per cent did not state their religion.[75]

Chadderton's population has been described as broadly working class with pockets of lower middle class communities, particularly in the northeast of the town, near the border with Royton.[76][42]

| Population growth in Chadderton since 1901 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

| Population | 24,892 | 28,299 | 28,721 | 27,450 | 30,571 | 31,124 | 32,568 | 32,450 | 33,518 | 34,026 | 33,001 | 34,818 |

| Urban District 1901–1971[77] • Urban Subdivision 1981–2001[78][79][80] | ||||||||||||

Economy

editUp until the 18th century, the inhabitants of Chadderton raised domestic farm animals, supplementing their incomes by the spinning and weaving wool in the domestic system. Primitive coal mining was established by the 17th century, and the factory system adopted in the late-18th century.[6] During the Victorian era, Chadderton's economy was heavily dependent on manufacturing industries, especially the spinning of cotton, but also the weaving of silk and production of hats.[20][35] By the 20th century the landscape was covered with over 50 cotton mills.[6] Industries ancillary to these sectors, including coal mining, brick making, mechanical engineering, and bleaching and dyeing were present.[20] Chadderton developed an extensive coal mining sector auxiliary to Chadderton's cotton industry and workforce. Coal was transported out of the township via the Rochdale Canal. The amount of coal was overestimated however, and production began to decline even before that of the local spinning industry; Chadderton's last coal mine closed in 1920.[81]

Since the deindustrialisation of the region in the mid-20th century, these industries have been replaced by newer sectors and industries,[20] although many of the civic developments that accompanied industrialisation remain in the form of public buildings; a town hall, public baths and library.[6] The few surviving cotton mills are now occupied by warehousing and distribution companies, or used as space for light industry.[82]

British aircraft manufacturer Avro built a factory in south Chadderton in 1938–39,[20][83] later known as BAE Chadderton. It was one of the largest employers in the area, producing a variety of aircraft models including Ansons, Manchesters and Bristol Blenheims.[83] During the Second World War, 3,050 Avro Lancaster bombers were built at the Chadderton factory—over 40 per cent of the Royal Air Force's fleet.[20][84] Post World War Two the Avro Vulcan was designed and built, as well as the Avro Shackleton and Avro Lincoln. After the Aircraft and Shipbuilding Industries Act 1977, Avro became part of the nationalised British Aerospace (now BAE Systems) and produced commercial aircraft for Boeing and Airbus.[85][86] It closed in 2012.[87]

Chadderton has been described as a "relatively prosperous town ... which makes it a popular residential area".[6] Chadderton Mall is a shopping precinct located in the town centre, and is one of Chadderton's main concentrations of retailing. It was constructed in 1974, and opened in 1975. It included at the time an Asda superstore which originally anchored the precinct, or district centre as the shopping precinct was originally known as, but moved to a new site on land just behind the original store in 1994, and it also contains a variety of smaller shops.[88] The Stationery Office has a base in Chadderton, as does 3M. In 2008, 3M was the centre of a high-profile robbery of over 3,000 British passports.[89][90][91] Other major businesses include Costco and Shop Direct Group.[92] The centre (formerly Elk Mill Retail Park),[93] is a retail park located at the start of the A627(M) motorway.[64]

Landmarks

editChadderton Town Hall was the seat of Chadderton Urban District Council. It is Chadderton's second town hall, the first was the former Chadderton Lyceum building (demolished in 1975). The current town hall, Chadderton's first purpose built municipal building, was designed by Taylor and Simister of Oldham, and was opened in 1913 by Herbert Wolstencroft JP, the then chairman of Chadderton Urban District Council. The architectural style was intended to have "a broad and strong treatment of the English Renaissance".[47] It features "charming gardens and a beautifully renovated ballroom".[94] English Heritage granted it Grade II listed status in July 2013.[95] Since 2007, Chadderton Town Hall has housed the Oldham Register Office, the civil registration authority for the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham.[96][97] It is a licensed venue for marriage ceremonies, and holds records of births, marriages and deaths which have taken place in what is now the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham from 1837 to the present.[97]

Foxdenton Hall is a two-storey Georgian mansion and former manor house, with an English garden wall bond exterior and its own private gardens.[98] The original Hall was erected in the mid-15th century as a home for the Radclyffes, who had acquired the title of joint Lords of the Manor with the Asshetons of Chadderton, through marriage. This Foxdenton Hall was demolished to make way for a second Hall, built in 1620. The ground floor of that second Hall now forms the basement of the present Hall, built in 1700.[99] The building is described as "a dignified early Georgian house, particularly rare in this part of the country".[98] The Radclyffes moved out of Foxdenton Hall in the late 18th century, favouring properties they had purchased in Dorset, although they still maintained ownership.[99] Foxdenton Hall and the adjoining Foxdenton Park were leased to Chadderton Council by the Radclyffes in 1922, when they opened to the public. In 1960 the council took over ownership of the Hall, by which time it was in a state of disrepair. Following protest about funding and the condition of the building, Foxdenton Hall was restored in 1965.[100]

Chadderton War Memorial is located outside Chadderton Town Hall, and was originally erected "in honour of the men of Chadderton who made the supreme sacrifice and in grateful remembrance of all who served their county" during the First World War, but later, the Second World War. It is a granite obelisk fronted by three steps. At the front on a short plinth stands a bronze figure of an ordinary soldier, holding a rifle in his right hand. It was designed by Taylor and Simister and sculpted by Albert Toft. Chadderton War Memorial was commissioned by the Chadderton War Memorial Committee and unveiled on 8 October 1921 by Councillor Ernest Kempsey.[101]

Chadderton Hall Park is a public park by the River Irk in the north of Chadderton, spanning an area of over 15 acres (6 ha),[102] in what were once the gardens of the manorial Chadderton Hall. At the end of the 19th century they were leased to Joseph Ball, who transformed the hall and grounds into a pleasure garden, complete with a boating lake and a menagerie.[103] The hall was demolished in 1939. The park is now owned by Oldham Council, the local authority, and was opened to the public in 1956. It was awarded Green Flag status in 2006.[102][104]

Transport

editPublic transport in Chadderton is co-ordinated by Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM), a county-wide public body with direct operational responsibilities, such as supporting (and in some cases running) local bus services and managing integrated ticketing in Greater Manchester.

Roads

editMajor A roads link Chadderton with other settlements, including the A663 road. Opened by Wilfrid William Ashley, 1st Baron Mount Temple in 1925, the arterial A663, named Broadway, bisects Chadderton from north to south and was "a major factor in the unification and modernisation of the town".[20] The A669 road, routed through Chadderton, connects Oldham with Middleton. At its eastern end is Chadderton's town centre. The M62 motorway runs to the north of the area and is accessed via Broadway at junction 21 and junction 20 via the A627(M) motorway, which terminates close to Chadderton's north-eastern boundary with Royton.[64] The M60 motorway skirts the south of Chadderton, near Hollinwood.[6] The section of the M60 through Chadderton was opened in autumn 2000.[105]

Railway

editChadderton is served by two railway stations, just outside its western boundary: Mills Hill railway station, at its border with Middleton, and Moston railway station, at its border with New Moston, Manchester.[citation needed]

The Middleton Junction and Oldham Branch Railway was routed through Chadderton. Middleton Junction railway station was within the town limits. Opened on 31 March 1842, it closed in 1966. On 12 August 1914, Chadderton goods and coal depot was opened. The depot was at the end of a 1097 yards long branch which came off the Middleton Junction to Oldham line at Chadderton Junction.[106] The line from Chadderton Junction to Oldham Werneth was closed on 7 January 1963, but Chadderton goods and coal depot remained open for a period.[107] Electric tramways to and from Middleton opened in 1902. Tram services ran along Middleton Road and terminated in Chadderton. The final tram ran in 1935.[108]

The Oldham Loop Line closed as a heavy rail line in 2009 and reopened in June 2012 as part of a new Manchester Metrolink light rail line from Manchester Victoria to Rochdale, via Oldham. South Chadderton, Freehold and Hollinwood were part of the conversion to Metrolink.[109][110] Proposals to extend the Metrolink system through Chadderton were announced in January 2016; the proposed link would add a spur between Westwood tram stop and Middleton with the line continuing to the Bury line near Bowker Vale.[111]

Buses

editThe majority of the bus services in Chadderton are operated by First Greater Manchester, who run services 24, 58, 59, 181 and 182, which provide frequent services from Chadderton town centre to Middleton, Oldham and Shaw, with other services running to Manchester, Royton and Rochdale. Manchester Community Transport run services 159 and 419 linking the town centre with Oldham, Middleton, Hollinwood, Woodhouses, Failsworth, New Moston, Werneth and Ashton-under-Lyne.[citation needed] Service 415 links the Cowhill and Nimble Nook areas of Chadderton with Middleton and Oldham, while services 81 and 81a operate through South Chadderton providing services to Manchester via Moston and to Oldham, Holts and Derker. These services are operated by First Greater Manchester.[64][112]

In the North Chadderton area, Rosso operate service 412 to Middeton via Mills Hill and Boarshaw and to Oldham via Royton while First Bus operate service 149 from Park Estate to North Manchester General Hospital via Oldham, Hollinwood and Blackley.[citation needed]

In the Greengate area of the town Stagecoach Manchester provides the following bus services. 112/113 – to Middleton via Middleton Junction and to Manchester city centre via Moston and Collyhurst. 114 – to Middleton via Alkrington and Manchester City Centre via Moston and Collyhurst. 294 offers two early morning one way services to the Trafford Centre via Moston, Cheetham Hill and Salford Quays.[citation needed] Citibus was a Chadderton-based commercial bus operator serving Greater Manchester, launched in 1986. It competed with the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive until 1995, when it was bought-out by GM Buses North, in what is now First Manchester.[113]

Education

editAn old style grammar school at Healds Green in Chadderton was built and founded in 1789.[114] As the population of Chadderton grew during the 19th century, more schools were opened, each linked with a local church.[35] Mills Hill School began as a voluntary aided school belonging to the local Baptist church.[114] Further schoolrooms from this period were found at Cowhill Methodist Church and Washbrook Methodist Church, opened in 1855 and 1893 respectively.[115]

Chadderton Grammar School was the first new style co-educational grammar school opened by Lancashire County Council. It was opened by David Lindsay, 28th Earl of Crawford, on 18 October 1930. In 1959, it became the Girls' Grammar, when a separate school for boys was opened. The Girls' Grammar briefly became Mid-Chadderton School, and later The Radclyffe School, and the boys' school part of North Chadderton School.[114][116] Radclyffe and North Chadderton are today the town's two co-educational, non-denominational, comprehensive secondary schools.[6] North Chadderton School has a sixth form college for 16- to 19-year-olds. The Radclyffe School, which has specialist Technology College status, was modernised in 2008 by way of a £30 million new school complex opened by Sir Alex Ferguson on 8 July 2008.[117] The Blessed John Henry Newman RC College opened in 2011 on the Broadway site previously occupied by The Radclyffe School.[citation needed]

Religion

editChadderton had no medieval church of its own,[118] and until 1541, for ecclesiastical purposes, lay within the parish of Prestwich-cum-Oldham in the Diocese of Lichfield. The diocese was then divided, and Chadderton became part of the Diocese of Chester.[17] This in turn was divided in 1847, when the present Diocese of Manchester was created. For ritual baptisms, marriages and burials, the people of Chadderton, a Christian community, had to travel to churches that lay outside of the township's boundaries, including Oldham St Mary's, Middleton St Leonard's, and Prestwich St Mary's. The route of some of the ancient paths to these churches is preserved in the modern layout of some of the town's roads.[119]

Chadderton's first established church was St Margaret of Antioch which was consecrated in 1769 at Hollinwood, however late 19th century boundary changes means it now lies within neighbouring Oldham.[120][121]

The New Parishes Act 1844 allowed for the creation of a parish for Chadderton, dedicated to St Matthew the Evangelist. Services were initially held in the stables of Chadderton Hall, and then in a temporary wooden structure opened in 1848.[122][123] The Church of St Matthew was opened for the parish in 1857 by the then Bishop of Manchester, James Prince Lee.[122][123] A steeple was added in 1881.[122] Following the construction of this church, four followed. There are now several Anglican parishes, and within them daughter and mission churches, serving the town.[118] The parish of St Matthew united with the neighbouring parish of St Luke, and the United Benefice of St Matthew with St Luke now lies within the Oldham West Deanery of the Diocese of Manchester.[124] The parish of Christ Church, founded in 1870, which also contains the church of St Saviour's and Crossley Christian Centre, is one of the largest numerically in the township and lies on the border with Werneth. The parish of Emmanuel, now meeting in the St George's building on Broadway, was originally part of Christ Church parish. Also within this deanery is the Parish Church of St Mark, built in the early 1960s. It is a blue brick building with a graduated slate pitched roof, and a rectangular brick steeple with a high gabled roof.[125] It was granted Grade II listed building status in 1998.[125]

In addition to the Church of England, a variety of other Reformed denominations have been practised in Chadderton. Nonconformism was popular in Chadderton, and places of worship for Methodism, Baptist and Congregationalism were built during the 19th and 20th centuries.[118] Washbrook Methodist Church and School at Butler Green was built in 1868, but was demolished around 1970 to be replaced by South Chadderton Methodist Church formed from the amalgamation of five Methodist congregations.[126]

Chadderton forms part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Salford. The Roman Catholic Parish of Corpus Christi was founded in Chadderton in 1878, following immigration to the region by Irish Catholics fleeing the Great Famine. A combined school and church was opened in 1904.[127] A further Catholic parish for Chadderton, dedicated to Saint Herbert, was created in 1916.[127] Its first mass was held on 1 July 1916, the day the Battle of the Somme began.[127]

Chadderton also has a large mosque to provide for the growing Muslim sector of the community. This is namely Chadderton Shahparan Central Mosque & Islamic Centre, and is located at 209–211 Bamford Street. The mosque has a large visitor capacity, and is open all throughout the day for quiet contemplation & other religious duties. The mosque is looked after by its own individual, specialist Mosque Committee.[citation needed]

Sport

editChadderton F.C. is an association football club, formed in 1947 under the name Millbrow Football Club; it later changed to North Chadderton Amateurs, before adopting its present name in 1957.[128] It plays in the North West Counties Football League First Division. Past players have included former England national football team captain David Platt, former Leeds United A.F.C. and Crystal Palace F.C. player John Pemberton and Northern Ireland national football team player Steve Jones.[128] Mark Owen of pop group Take That briefly played for the club.[128] Chaddertonians A.F.C. were formed in 1937 and currently play in the Lancashire Amateur League.[129] Chadderton Park F.C. is an amateur football club founded in 1977.[130] Oldham Borough F.C., formerly Oldham Dew and Oldham Town, were a Chadderton-based North West Counties League football club formed in 1964. They played at Nordens Road, Chadderton before moving to the Whitebank Stadium in Oldham in the early 1990s.

An earlier, but short-lived, version of Chadderton F.C. briefly played in the Manchester Football League in the early part of the 20th century. Joining the league in the 1905–06 season, the club ran into serious difficulties and were unable to complete the season. The club's record for the season was expunged.[131]

The Art Nouveau Chadderton Baths was a public swimming facility opened in 1937.[6] Henry Taylor, the British Olympic freestyle swimming triple gold medallist and champion was an attendant at Chadderton Baths, where many of his awards were displayed.[132][133] Chadderton Baths were closed indefinitely in 2006 after a structural survey found faults which could have put the public at risk.[134] Chadderton Sports Centre, built onto the baths, was closed and replaced by the Chadderton Wellbeing Centre in January 2010. An application to demolish the baths was made in March 2011,[135] but is now in private ownership with conversion work due soon. The Wellbeing Centre is a multi-purpose facility with a swimming pool, dance studio, library, gym, meeting rooms and café.[136]

Public services

editPolicing in Chadderton is provided by the Greater Manchester Police. The force's "(Q) Division" has its headquarters for policing the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham in central Oldham. Greater Manchester Police have two stations in Chadderton: a Victorian building in central Chadderton, and a modern purpose-built station at Broadgate in southern Chadderton.[137][138] Statutory emergency fire and rescue service is provided by the Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service, who have a fire station in Chadderton, on Broadway.[139]

There are no hospitals in Chadderton—the nearest are in the larger settlements of Oldham and Rochdale—but some local health care is provided by Chadderton Town and South Chadderton health centres which are commissioned by NHS Oldham. The North West Ambulance Service provides emergency patient transport in the area. Other forms of health care are provided for locally by several small specialist clinics and surgeries.[citation needed]

Waste management is co-ordinated by the local authority via the Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority.[140] Locally produced inert waste for disposal is sent to landfill at the Beal Valley.[141] United Utilities manages Chadderton's drinking and waste water.[142] Water supplies are sourced from several reservoirs in the borough, including Dovestones and Chew.[143] A sewage treatment works is located in the southwest of Chadderton, at Foxdenton. It opened in 1898.[6]

A power station in Chadderton existed in as early as 1925, built for the County Borough of Oldham in the Slacks Valley.[144] This structure was demolished to make way for the new Chadderton "B" Power Station, opened in 1955 for the British Electricity Authority in anticipation that the region would experience increased demand for electricity.[145][146] Structural changes to the National Grid made the power station redundant in 1982.[147] It was sold by the Central Electricity Generating Board in 1984, and demolished in 1986.[144][148] Chadderton's distribution network operator for electricity is United Utilities.[142]

Notable people

editPeople from Chadderton are called Chaddertonians. Historically, Chadderton was chiefly distinguished by the presence of ruling families, including the Asshetons, Radclyffes, Hortons and Chaddertons. Within the extended Chadderton/Chaderton family, two ecclesiastically notable persons were William Chaderton (medieval academic and bishop) and Laurence Chaderton (the first Master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, a leading Puritan and one of the original translators of the Authorised King James Version of the Bible).[14] John Ashton of Cowhill and Thomas Buckley of Baretrees in Chadderton were two victims of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819.[10][20] Samuel Collins, 'The Bard Of Hale Moss', was a 19th-century poet and radical who lived at Hale Moss in southern Chadderton.[149]

Lydia Becker was a pioneer in the late 19th century of the campaign for Women's Suffrage and founder of the Women's Suffrage Journal, born in Chadderton's Foxdenton Hall.[84] Chadderton born scientist Geoff Tootill helped create the Manchester Baby in 1948, the world's first electronic stored-program computer.[150] Terry Hall was a pioneering ventriloquist and early children's television entertainer born in Chadderton in 1926.[151][152] He was one of the first ventriloquists to perform with an animal (the "cowardly and bashful" Lenny the Lion) as his puppet, rather than a traditional child doll.[151][152] Other notable people from Chadderton include Woolly Wolstenholme, the Chadderton-born vocalist and keyboard player with the British progressive rock band Barclay James Harvest,[153] David Platt, former captain of the England national football team,[154][155][156] and supermodel Karen Elson, who grew up in the town and attended North Chadderton School.[157][158][159] Professor Ronald Whittam from Butler Green was born in 1925 and is a physiologist who made discoveries in cell physiology.[160][161] Professor Brian Cox was born in Chadderton in 1968.[citation needed] William Ash, is a Chadderton-born actor who has appeared in productions such as Waterloo Road and Hush.[162], while Robert Stewart - one of the last executioners in British judicial history - lived in Chadderton.[163]

See also

editReferences

editNotes

- ^ Historic England, "Manor Mill (1244330)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 22 December 2008

- ^ Historic England, "Chadderton Mill (1376626)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 22 December 2008

- ^ James, Alan. "A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence" (PDF). SPNS – The Brittonic Language in the Old North. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Chadderton Area Plan (PDF), oldham.gov.uk, January 2004, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ University of Nottingham's Institute for Name-Studies, Chadderton, nottingham.ac.uk, retrieved 17 June 2008

- ^ Ballard 1986, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Bateson 1949, p. 3

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brownbill & Farrer 1911, pp. 115–121.

- ^ a b c Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 4.

- ^ a b McNeil & Nevell 2000, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ordnance Survey Lancashire Sheet 97.05", Chadderton (1907 ed.), Alan Godfrey Maps, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84151-159-7

- ^ a b c d e Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 5.

- ^ Horn, Smith & Mussett 2004, pp. 37–42.

- ^ Bateson 1949, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e "Ordnance Survey Lancashire Sheet 97.01", North Chadderton & SW Royton (1932 ed.), Alan Godfrey Maps, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84784-157-5

- ^ a b McNeil & Nevell 2000, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 8.

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 63.

- ^ a b Frangopulo 1977, p. 30.

- ^ Cole & Postgate 1946, p. 214.

- ^ McPhillips 1997, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Reid 1989, p. 125.

- ^ Marlow 1969, p. 95.

- ^ Marlow 1969, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Aspin 1981, p. 4.

- ^ Gurr & Hunt 1998, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 7.

- ^ a b Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 27.

- ^ McPhillips 1997, p. 13

- ^ Norwich 2004, p. 497.

- ^ Gurr & Hunt 1998, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d Lewis 1848, pp. 538–542.

- ^ "Heritage; The History of Oldham; Oldham History", Internet Archive, visitoldham.co.uk, archived from the original on 6 August 2007, retrieved 11 September 2009

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 44.

- ^ Gurr & Hunt 1998, p. 17.

- ^ Aspin 1981, pp. 29–31.

- ^ a b c "Chadderton", Internet Archive, visitoldham.co.uk, archived from the original on 23 January 2008, retrieved 11 September 2009

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 3.

- ^ a b Urbanism, Environment and Design (URBED) (April 2004), Oldham Beyond; A Vision for the Borough of Oldham (PDF), Oldham.gov.uk, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2007, retrieved 24 December 2008

- ^ a b Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 8.

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 10.

- ^ "BAE Chadderton, birthplace of Lancaster bomber, closes", BBC News, 2 March 2012, archived from the original on 4 March 2012, retrieved 23 May 2012

- ^ Briggs 1971, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 31.

- ^ Brownbill & Farrer 1911, pp. 143–150.

- ^ Daly, p. 29.

- ^ Local Notes and Gleanings: Oldham and Neighborhood in Bygone Times, Published 1888 |Retrieved 30 March 2016

- ^ a b c Greater Manchester Gazetteer, Greater Manchester County Record Office, Places names – C, archived from the original on 18 July 2011, retrieved 17 June 2008

- ^ Bateson 1949, p. 209.

- ^ Tourist Information in Oldham, oldham.gov.uk, archived from the original on 6 March 2007, retrieved 1 May 2007

- ^ Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Local Government Act 1972. 1972 c.70.

- ^ Oldham Council, Interactive Planning Map, oldham.gov.uk, archived from the original on 8 March 2008, retrieved 30 July 2008

- ^ "FreeUK – Customer information". freeuk.com. 1 November 2017. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013.

- ^ Great Britain Historical GIS Project (2004), "Descriptive Gazetteer Entry for Oldham", A vision of Britain through time, University of Portsmouth, archived from the original on 14 November 2007, retrieved 2 November 2007

- ^ The Churchill Centre (14 October 2008), Churchill's Elections, winstonchurchill.org, archived from the original on 2 October 2009, retrieved 11 September 2009

- ^ Office for National Statistics (2001), "Census 2001:Key Statistics for urban areas in the North; Map 3" (PDF), United Kingdom Census 2001, statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009, retrieved 13 September 2007

- ^ Office for National Statistics (2001), "Greater Manchester Urban Area", United Kingdom Census 2001, statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 5 February 2009, retrieved 24 December 2007

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. (direct: Final Revised Paper Archived 3 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ a b "Climate: Chadderton". climate-data.org. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Aspin 1981, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (2010), Network Maps: Oldham (PDF), gmpte.com, retrieved 28 January 2010[permanent dead link]

- ^ A new and comprehensive gazetteer of England and Wales, illustr. by a series of maps. 4 vols. [in 2], James Bell,Published 1836, Original from Oxford University, Digitized 16 March 2007

- ^ "The parish of Prestwich with Oldham: Chadderton – British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013.

- ^ "The parish of Prestwich with Oldham: Oldham – British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011.

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS06 Ethnic group , 22 July 2004, archived from the original on 12 September 2011, retrieved 5 August 2008

- ^ Office for National Statistics, "Oldham Metropolitan Borough ethnic group", United Kingdom Census 2001, statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 13 June 2011, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ Office for National Statistics, "Greater Manchester Urban Area", United Kingdom Census 2001, statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 5 February 2009, retrieved 29 July 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS01 Usual resident population , 22 July 2004, archived from the original on 12 September 2011, retrieved 20 September 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS04 Marital status , 22 July 2004, archived from the original on 12 September 2011, retrieved 31 August 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS20 Household composition , 22 July 2004, archived from the original on 12 September 2011, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS13 Qualifications and students , 22 July 2004, archived from the original on 12 September 2011, retrieved 5 August 2008

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS07 Religion , 22 July 2004, archived from the original on 12 September 2011, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ Criddle & Waller 2002, p. 602.

- ^ Great Britain Historical GIS Project (2004), "Chadderton UD through time. Population Statistics. Total Population", A vision of Britain through time, University of Portsmouth, archived from the original on 5 January 2012, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ 1981 Key Statistics for Urban Areas GB Table 1, Office for National Statistics, 1981

- ^ 1991 Key Statistics for Urban Areas, Office for National Statistics, 1991

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS01 Usual resident population , 22 July 2004, archived from the original on 12 September 2011, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 45.

- ^ Hyde, O'Rourke & Portland 2004, p. 117

- ^ a b Stratton & Trinder 2000, p. 76.

- ^ a b Manchester City Council, Oldham, spinningtheweb.org.uk, archived from the original on 24 May 2012, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ Commons Hansard: 26 Feb 2004 : Column 154WH, parliament.the-stationery-office.co.uk, 26 February 2004, archived from the original on 4 June 2011, retrieved 23 December 2008

- ^ Harrison, Michael (28 November 2001), 1,700 jobs axed as BAE quits the regional aircraft industry, independent.co.uk, retrieved 2 January 2009[dead link]

- ^ "BAE Chadderton, birthplace of Lancaster bomber, closes", BBC News, 2 March 2012, retrieved 13 October 2019

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 38.

- ^ McSmith, Andy (30 July 2008), "Thousands of passports and visas stolen from van", The Independent, London, archived from the original on 8 April 2009, retrieved 2 January 2009

- ^ Barker, Janice (29 July 2008), 3,000 passports stolen from van, oldham-chronicle.co.uk, archived from the original on 24 July 2011, retrieved 24 December 2008

- ^ Leroux, Marcus (31 July 2008), "Passport theft police 'arrest delivery man'", The Times, London, archived from the original on 4 June 2011, retrieved 2 January 2009

- ^ Workers shocked as 475 jobs are axed, thisislancashire.co.uk, 16 June 2004, archived from the original on 12 November 2014, retrieved 26 December 2008

- ^ "New superstore has everything – but food", Oldham Advertiser, M.E.N. Media, 31 January 2007, archived from the original on 13 September 2012, retrieved 27 July 2008

- ^ Oldham Council, Chadderton Town Hall, oldham.gov.uk, archived from the original on 29 June 2008, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ Historic England. "Chadderton Town Hall and associated walls and walled garden, Middleton Road, Chadderton (Grade II) (1404904)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Greer, Stuart (4 July 2007), "Wedding bells ring out again", Oldham Advertiser, M.E.N. Media, archived from the original on 22 September 2012, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ a b Oldham Council, Births, Marriages and Deaths, oldham.gov.uk, archived from the original on 19 November 2008, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ a b Historic England, "Foxdenton Hall (1356429)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 24 February 2008

- ^ a b Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 12.

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 13.

- ^ Public Monuments and Sculpture Association (16 June 2003), Chadderton War Memorial, archived from the original on 12 November 2014, retrieved 12 November 2014

- ^ a b Green Flag Award, "Chadderton Hall Park", Internet Archive, greenflagaward.org.uk, archived from the original on 7 February 2008, retrieved 28 January 2010

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1990, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Awards, oldhamparks.co.uk, archived from the original on 23 July 2008, retrieved 23 December 2008

- ^ Hyde, O'Rourke & Portland 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Central Lines, Britishrailways1960.co.uk, archived from the original on 27 February 2012, retrieved 5 May 2012

- ^ Central Lines, Britishrailways1960.co.uk, archived from the original on 13 November 2016, retrieved 5 May 2012

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1990, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Light Rail Transit Association (24 November 2007), Manchester to Oldham and Rochdale, lrta.org ork, archived from the original on 11 February 2012, retrieved 1 May 2008

- ^ Oldham and Rochdale line, Transport for Greater Manchester, archived from the original on 18 May 2013, retrieved 19 May 2013

- ^ "Oldham News | News Headlines | Jim's loop lines vision for trams - Chronicle Online". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016. | Retrieved 31 October 2016

- ^ "Service 152 Chadderton – Firwood Park" (PDF). Stagecoach. 21 July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2013.

- ^ Greater Manchester Transport Society (2007), Deregulated Bus Operators: 1986 onwards, gmts.co.uk, archived from the original on 9 November 2010, retrieved 24 January 2010

- ^ a b c Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 24.

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1990, p. 22.

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 25.

- ^ "Fergie's fan club", Oldham Advertiser, M.E.N. Media, 9 July 2008, archived from the original on 29 June 2011, retrieved 21 December 2008

- ^ a b c Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 85.

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 15.

- ^ "The parish of Prestwich with Oldham: Chadderton – British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015.

- ^ (from parish history, 1769 to 1996 by Barry Dainty) (1996). "A Short History of the Parish of S. Margaret Hollinwood and S. Chad Limeside". www.magsnchads.org.uk. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Lawson & Johnson 1990, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b History – St Matthew, stmatthew-stlukechadderton.org.uk, archived from the original on 24 December 2012, retrieved 6 November 2008

- ^ Anglican Diocese of Manchester, Tandle Deanery, manchester.anglican.org, archived from the original on 9 September 2012, retrieved 5 November 2008

- ^ a b Historic England, "Church of St Mark, Milne Street (1376598)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 22 December 2008

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1990, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 90.

- ^ a b c Club History, chaddertonfc.org.uk, archived from the original on 12 September 2011, retrieved 22 January 2010

- ^ Chaddertonians AFC, clubwebsite.co.uk, 20 December 2008, archived from the original on 18 April 2009, retrieved 22 December 2008

- ^ The History of Chadderton Park Juniors Football Club, chaddertonparkfc.co.uk, archived from the original on 21 November 2008, retrieved 22 December 2008

- ^ "The Manchester League 1893-1912". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2018. | The Manchester League 1893–1912 |Retrieved 27 February 2018

- ^ Janice Barker (20 August 2008), "Another 24 hours, another Olympic record", Oldham Evening Chronicle, archived from the original on 26 August 2008, retrieved 29 August 2008

- ^ "Henry's record still stands", Oldham Advertiser, M.E.N. Media, 20 August 2008, archived from the original on 10 September 2012, retrieved 28 August 2008

- ^ Sykes, Lee (30 August 2006), "Is this the end for Chadderton baths?", Oldham Advertiser, M.E.N. Media, archived from the original on 22 September 2012, retrieved 23 December 2008

- ^ Doherty, Karen (31 March 2011), Baths demolition moves step closer, Oldham Evening Chronicle, archived from the original on 5 January 2012, retrieved 12 December 2011

- ^ Chadderton Wellbeing Centre, Oldham Community Leisure, archived from the original on 22 December 2011, retrieved 12 December 2011

- ^ Greater Manchester Police Authority, Local Policing in Oldham 2007–2008 (PDF), gmpa.gov.uk, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009, retrieved 21 December 2008

- ^ Greater Manchester Police, Your Neighbourhood Area Policing Team, gmp.police.uk, archived from the original on 20 March 2009, retrieved 11 September 2009

- ^ Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service, Chadderton Fire Station, manchesterfire.gov.uk, archived from the original on 18 January 2012, retrieved 12 December 2011

- ^ Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority (2008), Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority (GMWDA), gmwda.gov.uk, archived from the original on 7 February 2008, retrieved 8 February 2008

- ^ Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council, Minerals and Waste development planning, oldham.gov.uk, archived from the original on 23 November 2012, retrieved 8 February 2008

- ^ a b United Utilities (17 April 2007), Oldham, unitedutilities.com, archived from the original on 22 April 2008, retrieved 8 February 2008

- ^ United Utilities (17 April 2007), Dove Stone Reservoirs, unitedutilities.com, archived from the original on 22 April 2008, retrieved 8 February 2008

- ^ a b Department of the Environment (1994), Documentary Research on Industrial Sites: CLR Report 3 (PDF), eugris.info, archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2009, retrieved 28 January 2010

- ^ India-Rubber Journal, vol. 125, July–December 1953, p. 291

- ^ Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester (2001), Power Stations in Greater Manchester (PDF), msim.org.uk, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009, retrieved 23 December 2008

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 73.

- ^ Lawson & Johnson 1997, p. 2.

- ^ http://richardjohnbr.blogspot.co.uk/2007/08/chartist-lives-samuel-collins.html%7CChartist Lives – Samuel Collins. Retrieved 17 July 2013

- ^ Taylor, Paul (20 June 2008), "Baby changed the world", Manchester Evening News, M.E.N. Media, archived from the original on 3 March 2011, retrieved 20 August 2008

- ^ a b "Terry Hall: Pioneering ventriloquist who turned a variety act into a television institution for all the family", The Times, London, 14 April 2007, retrieved 20 December 2008[dead link]

- ^ a b "Terry Hall", The Telegraph, London: Telegraph Media Group, 12 April 2007, archived from the original on 26 March 2010, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ Barclay James Harvest Biography, bjharvest.co.uk, archived from the original on 8 January 2009, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ Kay, Oliver (6 December 2002), "The error that let Henry slip through United net", The Times, London, archived from the original on 4 June 2011, retrieved 2 January 2009

- ^ Wright, James, "Englishmen Abroad: David Platt", Internet Archive, The Football Association, archived from the original on 12 March 2005, retrieved 11 September 2009

- ^ David Platt Profile, givemefootball.com, archived from the original on 17 August 2010, retrieved 20 December 2008

- ^ North Chadderton School, North Chadderton Sixth Form, northchaddertonschool.co.uk, archived from the original on 18 September 2008, retrieved 11 September 2009

- ^ "A supermodel pupil drops in at her old school", The Borough Oldhamer, no. 26, p. 3, June–July 2005

- ^ Barker, Janice (9 September 2008), Chadderton's Karen is the new face of John Lewis, oldham-chronicle.co.uk, archived from the original on 24 July 2011, retrieved 29 December 2008

- ^ Ronald, Whittam. "Physiological Society - oral interview transcript" (PDF).

- ^ "Ronald Whittam". royalsociety.org. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Interview – William Ash". bbc.co.uk. 29 January 2004. Archived from the original on 10 December 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Harry had the regulars hanging on his every word". 6 April 2006.

Bibliography

- Aspin, Chris (1981), The Cotton Industry, Shire, ISBN 0-85263-545-1

- Ballard, Elsie (1986) [1967], A Chronicle of Crompton (2nd ed.), Burnage Press, ISBN 5-00-096678-3

- Bateson, Hartley (1949), A Centenary History of Oldham, Oldham County Borough Council, ISBN 5-00-095162-X

- Briggs, Geoffrey (1971), Civic and Corporate Heraldry: A Dictionary of Impersonal Arms of England, Wales and N. Ireland, Heraldry Today, ISBN 0-900455-21-7

- Brownbill, J.; Farrer, William (1911), A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 5, Victoria County History, ISBN 978-0-7129-1055-2

- Cole, G. D. H; Postgate, Raymond (1946), The Common People 1746–1946 (1964 reprint ed.), Methuen & Co

- Criddle, Byron; Waller, Robert (2002), Almanac of British Politics, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26833-8

- Daly, J. D., Oldham From the XX Legion to the 20th Century, ISBN 5-00-091284-5

- Frangopulo, Nicolas J. (1977), Tradition in Action: The Historical Evolution of the Greater Manchester County, Wakefield: EP Publishing, ISBN 0-7158-1203-3

- Gurr, Duncan; Hunt, Julian (1998), The Cotton Mills of Oldham, Oldham Education & Leisure, ISBN 0-902809-46-6

- Horn, Joyce; Smith, David M.; Mussett, Patrick (2004), Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1541–1857, vol. 11, University of London, Institute of Historical Research, ISBN 1-871348-12-9

- Hyde, M.; O'Rourke, A.; Portland, P. (2004), Around the M60: Manchester's Orbital Motorway, AMCD, ISBN 1-897762-30-5

- Lawson, Michael; Johnson, Mark (1990), Looking Back at Chadderton, Oldham Leisure Services, ISBN 0-902809-23-7

- Lawson, Michael; Johnson, Mark (1997), Images of England: Chadderton, Tempus, ISBN 0-7524-0714-7

- Lewis, Samuel (1848), A Topographical Dictionary of England, Institute of Historical Research, ISBN 978-0-8063-1508-9

- Marlow, Joyce (1969), The Peterloo Massacre, Rapp & Whiting, ISBN 0-85391-122-3

- McNeil, Robina; Nevell, Michael (2000), A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Greater Manchester, Association for Industrial Archaeology, ISBN 0-9528930-3-7

- McPhillips, K. (1997), Oldham: The Formative Years, Neil Richardson, ISBN 1-85216-119-1

- Norwich, John Julius (2004), AA Treasures of Britain (2nd ed.), Automobile Association, ISBN 978-0-7495-4226-9

- Reid, Robert (1989), The Peterloo Massacre, William Heinemann, ISBN 0-434-62901-4

- Stratton, Michael; Trinder, Barrie (2000), Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-419-24680-0

External links

edit- www.chadderton-hs.freeuk.com, Website of the Chadderton Historical Society.

- www.genuki.org.uk, the GENUKI page for Chadderton Township.