Cavite City, officially the City of Cavite (Chavacano: Ciudad de Cavite and Filipino: Lungsod ng Kabite) is a component city in the Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 100,674 people.[3]

Cavite City | |

|---|---|

| City of Cavite | |

|

Clockwise from top: New Cavite City Hall, Old Cavite City Hall, San Roque Parish Church, Heroes' Arch, and the Thirteen Martyrs Monument | |

Nicknames:

| |

| Motto(s): Para Dios y Patria ("For God and Country") | |

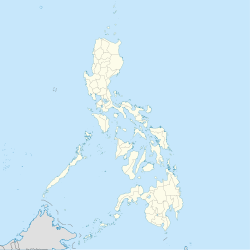

Map of Cavite with Cavite City highlighted | |

Location within the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 14°29′N 120°54′E / 14.48°N 120.9°E | |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | Calabarzon |

| Province | Cavite |

| District | 1st district |

| Settled | May 16, 1571 |

| Founded | 1614 |

| Cityhood | September 7, 1940 |

| Barangays | 84 (see Barangays) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Panlungsod |

| • Mayor | Denver Christopher R. Chua |

| • Vice Mayor | Benzen Raleigh G. Rusit |

| • Representative | Ramon Jolo Revilla |

| • City Council | Members |

| • Electorate | 71,003 voters (2022) |

| Area | |

• Total | 10.89 km2 (4.20 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 143rd out of 145 |

| Elevation | 15 m (49 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 169 m (554 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2020 census)[3] | |

• Total | 100,674 |

| • Density | 9,200/km2 (24,000/sq mi) |

| • Households | 27,473 |

| Economy | |

| • Income class | 4th city income class |

| • Poverty incidence | 12.71 |

| • Revenue | ₱ 806.3 million (2022) |

| • Assets | ₱ 2,082 million (2022) |

| • Expenditure | ₱ 659.6 million (2022) |

| • Liabilities | ₱ 412.8 million (2022) |

| Service provider | |

| • Electricity | Manila Electric Company (Meralco) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| ZIP code | 4100, 4101, 4125 |

| PSGC | |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)46 |

| Native languages | Chavacano Tagalog |

| Major religions | |

| Catholic diocese | Diocese of Imus |

| Patron saint | |

| Website | www |

The city was the capital of Cavite Province from its establishment in 1614 until the title was transferred to the newly created, more accessible city of Trece Martires in 1954. Cavite City was originally a small port town, Cavite Puerto, that prospered during the early Spanish colonial period, when it served as the main seaport of Manila. Cavite Puerto hosted the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade, along with other large sea-bound ships. Thereafter, San Roque and La Caridad, two formerly independent towns in Cavite province,[5] were annexed by the city. Today, Cavite City includes the communities of San Antonio (Cañacao and Sangley Point),[6] the southern districts of Santa Cruz and Dalahican, and the outlying islands of the province, such as the historic Corregidor Island.

Etymology

editThe city has been known by at least two Tagalog names. The first, Tangway, was the name given to the area by Tagalog settlers. Tangway means "peninsula." The second is Kawit or "hook," referring to the hook-shaped landform along the coast of Bacoor Bay,[6] and from which the Chinese Keit and Spanish Cavite are derived.[7]

History

editEarly history

editThe early inhabitants of Cavite City were the Tagalogs ruled by the Kampilan and the bullhorn of a datu, the tribal form of government.[citation needed] According to folklore, the earliest settlers came from Borneo, led by Gat Hinigiw and his wife Dayang Kaliwanag, who bore seven children.[citation needed] Archaeological evidence in the coastal areas shows prehistoric settlements.[citation needed]

Spanish colonial era

editOn May 16, 1571, the Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi declared the region a royal encomienda, or royal land grant.[citation needed] Spanish colonizers settled in the most populated area (present-day Kawit) and called it Cavite. The old Tangway at the tip of the Cavite Peninsula, across Bacoor Bay, was referred to as Cavite la Punta, meaning "Point of Cavite" or Cavite Point. Upon discovering that, because of its deep waters, Cavite la Punta was a suitable place for the repair and construction of Spanish galleons, the Spanish moved their settlement there and called it Cavite Nuevo (New Cavite) or just Cavite. The first settlement was renamed "Cavite Viejo" (and in the early 20th century, regained its former name, Kawit). In 1582, the Spanish founded Cavite City with 65 Spanish households.[8]

In 1590, the Spaniards fortified Cavite Nuevo/Cavite City with murallas (high thick curtain walls) on its western, northern, and eastern sides, while Bacoor Bay remained open to the south. Fort Guadalupe was built at the same time on the eastern tip, and the town became the Puerto de Cavite (Port of Cavite) or Cavite Puerto. The Fort of San Felipe Neri and the Porta Vaga Gate began construction in 1595 and were completed in 1602. Puerta Vaga (corrupted to Porta Vaga) was the port city's barbican, the only principal entrance from San Roque in the west. It was flanked by the western wall, protected by two bastions at its northern and southern ends. The wall and gate were also separated from the mainland by a moat, which made the town like an island.[9]

Cavite was legally founded in 1614 with Tomás Salazar as the earliest known gobernadorcillo recorded.[9] At the same time, the town became the capital of the new politico-military province of Cavite, established also in 1614.[10] Like some other provinces during the Spanish era, the province adopted the name of its capital town – e.g., Bulacan, Bulacan province; Tayabas, Tayabas (today, Quezon province); Tarlac, Tarlac province; and Manila, Manila province.

San Roque was founded as a separate town in 1614. In 1663, during the Spanish evacuation of Ternate, Indonesia, the 200 families of mixed Mexican-Filipino-Spanish and Papuan-Indonesian-Portuguese descent who had ruled over the Christianized Sultanate of Ternate, including their Christian-convert Sultan,[11] were relocated to the cities of Ternate (Cavite province), Ermita, Manila, and San Roque (Cavite province).[12]

In subsequent years, Latin-American soldiers from Mexico were deployed at Cavite: 70 soldiers in 1636; 89 in 1654; 225 in 1670; and 211 in 1672.[13]

San Roque was later placed under the civil administration of Cavite until it was granted the right to be a separate and independent municipality in 1720. La Caridad, formerly known as La Estanzuela of San Roque, separated and was legally founded as a town in 1868. The Spanish Governor General Jose de la Gardana granted the petition of the people led by Don Justo Miranda to make Barrio La Estanzuela an independent town.

By the end of the 1700s, Cavite was the main port of Manila and was a province of 5,724 native families and 859 Spanish Filipino families.[14]: 539 [15]: 31, 54, 113

City of Churches

editAs the town grew, it developed a cosmopolitan reputation, and attracted various religious orders to set up churches, convents, and hospitals within the confines of the fortified city center. The Franciscan Hospital de San Jose (Saint Joseph Hospital) was built for sailors and soldiers in 1591. The San Diego de Alcala Convent was built in 1608, followed by the Convents of Porta Vaga (La Ermita), Our Lady of Loreto (Jesuit), San Juan de Dios (St. John of God), Santo Domingo (Dominicans), Santa Monica (Recollects), and San Pedro, the port's parish church. The fortified town enclosed eight churches, the Jesuit college of San Ildefonso, public buildings and residences, all meant to serve the needs of its population of natives, soldiers and workers at the port, transients, and passengers aboard galleons.[9]

During this period, the city was called "Tierra de Maria Santisima" (Land of Most Holy Mary) because of the popularity of the Marian devotion.[citation needed] Plazas and parks abounded: Plaza de Armas (across from San Felipe Fort), Plaza de San Pedro (across from the church), Plaza Soledad (across from Porta Vaga), and Plaza del Reparo (bayside).

Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade

editThe Port of Cavite (Puerto de Cavite) was linked to the history of world trade. Spanish galleons passed back and forth every July between Acapulco (Mexico) and Cavite. Galleons and other heavy ocean-going ships were not able to enter the Port of Manila along the Pasig River because of a sand bar that only allows light vessels to reach the river-port. For this reason, the Port of Cavite was regarded as the Port of Manila,[16] the main seaport of the capital city.[17]

At the height of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade, the Port of Cavite was the arrival and departure port of the Spanish galleons that brought many foreign travelers (mostly Spaniards and Latinos) to its shores.[18][19] The Port of Cavite was fondly called Ciudad de Oro Macizo meaning the "City of Solid Gold". The Chinese emperor once sent some of his men to the place they called Keit (Cavite) to search for gold.[7] Marilola Perez, in her 2015 Thesis "Cavite Chabacano Philippine Creole Spanish: Description and Typology", describes a large number of Mexicans settling in Cavite and spreading to Luzon, integrating into the local population and leading peasant revolts.[20] Mexicans weren't the only Latin Americans in Cavite, as there were also a fair number of other Latin Americans. One of these was the Puerto Rican Alonso Ramirez, who became a sailor in Cavite, and published an influential early Latin American novel entitled "Infortunios de Alonso Ramirez"[21]

Between 1609 and 1616 the galleons Espiritu Santo and San Miguel were constructed in the shipyard of the port, called the Astillero de Rivera (Rivera Shipyard of Cavite), sometimes spelled as Ribera.[17]

San Roque Isthmus

editThe narrow San Roque isthmus or causeway (now M. Valentino Street) connected Cavite Puerto to San Roque, its only border town. Maps from the 17th century show that this narrow isthmus was once as wide as the town itself.[22] Problems with rising water and the encroaching waves that plagued Cavite Puerto likely eroded the land into a narrow isthmus.[23]

American Invasion Era

editSpain turned the port over to the Americans after the Treaty of Paris of 1898. At the start of the American era, Cavite Puerto became the seat of the U.S. Naval Forces in the Philippines. It was redesigned to make way for modern ships and armaments. The historical structures, like Fort Guadalupe, were demolished, along with most of Fort San Felipe.[9]

Local government administration was reorganized under the Presidentes municipales with the direct supervision of American army officers (the first being Colonel Meade). The first Filipino Presidentes municipales were appointed: Don Zacaria Fortich for Cavite Puerto, Don Francisco Basa for San Roque, and Don Pedro Raqueño Bautista for Caridad.

In 1900, the Caviteños held their first election under the American regime. Each pueblo or town elected local officials: Presidente municipal, Vice-Presidente municipal and a Consejo (council) composed of Consejales (councilors). Don Gregorio Basa was elected as the Presidente Municipal of present-day Cavite City.

In 1901, the Philippine Commission approved a municipal code as the organic law of all local governments throughout the country. In its implementation in 1903, the three separate pueblos of Cavite Puerto, San Roque, and La Caridad were merged into one municipality, which was called the Municipality of Cavite. By virtue of a legislative act promulgated by the First Philippine Assembly, Cavite was again made the capital of the province. Subsequently, its territory was enlarged to include the district of San Antonio and the island of Corregidor. The Municipality of Cavite functioned as a civil government whose officials consisted of a Presidente Municipal, a Vice-Presidente Municipal and ten Consejales duly elected by the qualified voters of the municipality.

In 1909, Executive Order No. 124, of Governor-General W. Cameron Forbes, declared the Act No. 1748 annexing Corregidor and the islands of Caballo (Fort Hughes), La Monja, El Fraile (Fort Drum), Santa Amalia, Carabao (Fort Frank) and Limbones, as well as all waters and detached rocks surrounding them, to the Municipality of Cavite.

Cityhood

editUnder the Philippine Commonwealth, Assemblyman Manuel S. Roxas sponsored Commonwealth Act No. 547, elevating Cavite's status to a chartered city. On September 7, 1940, the executive function of the city was vested in a City Mayor appointed by the President of the Philippine Commonwealth. The legislative body of the City of Cavite was vested on a Municipal Board composed of three electives, two appointives, and two ex-officio councilors, with the City Mayor as the presiding officer.

Japanese Occupation Era

editOn December 10, 1941, two days after an attack that had destroyed American air defenses at Clark Field and three days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese Imperial Forces destroyed Cavite Naval Base and bombed Cavite City.

Later, after Japan seized the Philippines, Japanese leaders appointed at least two City Mayors of Cavite City.

The island of Corregidor played an important role during the Japanese invasion of the Philippines. The island was the site of two costly sieges and pitched battles—the first in early 1942, and the second in January, 1945—between the Imperial Japanese Army and the U.S. Army, along with its smaller subsidiary force, the Philippine Army.

In 1945, during the fight to liberate the country from Japan, the US and Philippine Commonwealth militaries bombarded the Japanese forces stationed in the city, completely destroying the old historic port of Cavite. The old walls and the Porta Vaga Gate were damaged. Most of the structures were destroyed, but some of the church towers remained. The city was littered with bomb craters.[24]

After the war, the city's local administration resumed operations. The walls, gates, and ruins of the old city were later removed. Only the bell tower of the Church of Santa Monica of the Augustinian Recollects and the two bastions of Fort San Felipe remain from the old city.

Post-war era

editThird Republic (1946-1972)

editRepublic Act No. 981, passed by the Congress of the Philippines in 1954, transferred the capital of the province from Cavite City to the newly established Trece Martires. Subsequently, the city charter was amended. By virtue of an amendment to the charter of Cavite City, the City Mayor, City Vice Mayor and eight councilors were elected by popular vote. The first election of city officials in this way was held in 1963.

During the Marcos presidency and dictatorship (1965-1986)

editThe Philippines' gradual postwar recovery took a turn for the worse in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with the 1969 Philippine balance of payments crisis being an early landmark event.[25] Economic analysts generally attribute the crisis to the ramp-up on loan-funded government spending to promote Ferdinand Marcos’ 1969 reelection campaign.[25][26][27][28][29][30] In 1972, one year before the expected end of his last constitutionally allowed term as president, Ferdinand Marcos placed the Philippines Martial Law.[31] This allowed Marcos to remain in power for fourteen more years, during which Cavite endured many social and economic obstacles.[31] It was around the time Martial Law was declared, in 1972, that Mayor Manuel S. Rojas was assassinated in the nearby town of Bacoor, Cavite.[32]

The excesses of the Marcos Family[31] prompted opposition from various Filipino citizens despite the risks of arrest and torture[33] Victims of human rights abuses during this period included Cavite City resident and University of the Philippines student leader Emmanuel Alvarez. Alvarez, a descendant of Katipunan General Pascual Alvarez, became one of the desaparecidos of Martial law under Ferdinand Marcos when he was accosted by two men believed to be military personnel while commuting from his home in Cavite City on January 6, 1976, and never seen again.[34] He has formally been honored as a hero of Philippine democracy, having had his name etched on the wall of remembrance of the Philippines' Bantayog ng mga Bayani.[34]

During the 1986 snap elections, Marcos won against Corazon Aquino in Region IV (which then included the provinces of MIMAROPA) according to the official COMELEC results, but this was disputed by NAMFREL. An exit poll conducted by American election observers found that voters from Cavite City preferred Aquino over Marcos.[35]

Land reclamation

editIn the latter part of the 1960s and early 1970s, the land adjacent to the San Roque isthmus was reclaimed. The new land is now occupied by the San Sebastian College – Recoletos de Cavite and some residential homes. The present Cavite City Hall is built where the north tower of the old western wall once stood, which was already partly reclaimed by 1945.[24]

Half of the old port city, including Fort San Felipe, is now occupied by Naval Base Cavite and is closed to the public. The old historic core of Cavite is now part of the San Roque district, and is referred to today as either Fort San Felipe or Porta Vaga.[6] The former location of the Porta Vaga Gate, the western wall, and its towers is now occupied by the Governor Samonte Park.

Contemporary era

editA portion of Danila Atienza Air Base was converted into a domestic airport in 2020 called Sangley Point Airport.[36] The airport is planned to be converted into an international airport under the national government's Public-Private Partnership (PPP) program. The original proponent status (OPS) contract was initially awarded to a consortium between MacroAsia Corporation and China Communications Construction Company Ltd.,[37] until it was dropped by the provincial government in 2021.[38] After another round of bidding, the contract was awarded to the Yuchengco-led Sangley Point International Airport Consortium in 2022.[39]

Geography

editCavite City occupies most of the hook-shaped Cavite Peninsula that juts into Manila Bay. The peninsula is lined by Bacoor Bay to the southeast. The peninsula ends in two tips – Sangley Point and Cavite Point. Cañacao Bay is the body of water formed between the points. Cavite Point was the location of the old historic Port of Cavite. Both Bacoor and Cañacao Bays are inland bays within the larger Manila Bay. The city's only land border is with the Municipality of Noveleta to the south.

The city is the northernmost settlement in the Province of Cavite, which lies southwest from Manila with a direct distance of about 11 kilometers (6.8 mi) but about 35 kilometers (22 mi) overland/by road. Sangley Point, the former location of the United States Sangley Point Naval Base, is the northernmost point of the city, peninsula and province. The former American military naval base has since been converted into a Philippine military base.

The historic island of Corregidor, the adjacent islands and detached rocks of Caballo, Carabao, El Fraile and La Monja found at the mouth of Manila Bay are part of the city's territorial jurisdiction.

Climate

editCavite City has a tropical wet and dry climate (Köppen climate classification Aw), with a pronounced dry season from December to April, and a lengthy wet season from May to November that brings abundant rainfall into the city.

| Climate data for Cavite City (Danilo Atienza Air Base) 1991–2020, extremes 1974–2023 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.8 (94.6) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.6 (97.9) |

37.8 (100.0) |

38.5 (101.3) |

38.4 (101.1) |

36.4 (97.5) |

36.5 (97.7) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

36.4 (97.5) |

34.0 (93.2) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.3 (86.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

32.5 (90.5) |

34.3 (93.7) |

34.1 (93.4) |

33.1 (91.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

30.5 (86.9) |

32.0 (89.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.3 (81.1) |

27.8 (82.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.9 (85.8) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.9 (84.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.3 (75.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 19.0 (66.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 19.9 (0.78) |

20.4 (0.80) |

19.1 (0.75) |

17.7 (0.70) |

149.9 (5.90) |

260.4 (10.25) |

456.5 (17.97) |

514.3 (20.25) |

385.5 (15.18) |

196.9 (7.75) |

109.1 (4.30) |

91.6 (3.61) |

2,241.3 (88.24) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 13 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 114 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 77 | 75 | 73 | 76 | 80 | 83 | 84 | 84 | 81 | 80 | 80 | 79 |

| Source: PAGASA[40][41] | |||||||||||||

Subdivisions

editThe city proper is divided into five districts: Dalahican, Santa Cruz, Caridad, San Antonio, and San Roque. These districts are further subdivided into eight zones and a total of 84 barangays.

Barangays

editCavite City is politically subdivided into 84 barangays.[42] Each barangay consists of puroks and some have sitios.

- Barangay 1 (Hen. M. Alvarez)

- Barangay 2 (Hen. C. Tirona)

- Barangay 3 (Hen. E. Aguinaldo)

- Barangay 4 (Hen. M. Trias)

- Barangay 5 (Hen. E. Evangelista)

- Barangay 6 (Diego Silang)

- Barangay 7 (Kapitan Kong)

- Barangay 8 (Manuel S. Rojas)

- Barangay 9 (Kanaway)

- Barangay 10-M (Kingfisher)

- Barangay 10-A (Kingfisher A)

- Barangay 10-B (Kingfisher B)

- Barangay 11 (Lawin)

- Barangay 12 (Love Bird)

- Barangay 13 (Aguila)

- Barangay 14 (Loro)

- Barangay 15 (Kilyawan)

- Barangay 16 (Martines)

- Barangay 17 (Kalapati)

- Barangay 18 (Maya/Pisces)

- Barangay 19 (Gemini)

- Barangay 20 (Virgo)

- Barangay 21 (Scorpio)

- Barangay 22 (Leo)

- Barangay 22-A (Leo A)

- Barangay 23 (Aquarius)

- Barangay 24 (Libra)

- Barangay 25 (Capricorn)

- Barangay 26 (Cancer)

- Barangay 27 (Sagittarius)

- Barangay 28 (Taurus)

- Barangay 29 (Lao-lao/Aries)

- Barangay 29-A (Lao-lao A/Aries A)

- Barangay 30 (Bid-bid)

- Barangay 31 (Maya-maya)

- Barangay 32 (Salay-salay)

- Barangay 33 (Buan-buan)

- Barangay 34 (Lapu-lapu)

- Barangay 35 (Hasa-hasa)

- Barangay 36 (Sap-Sap)

- Barangay 36-A (Sap-sap A)

- Barangay 37-M (Cadena de Amor)

- Barangay 37-A (Cadena de Amor A)

- Barangay 38 (Sampaguita)

- Barangay 38-A (Sampaguita A)

- Barangay 39 (Jasmin)

- Barangay 40 (Gumamela)

- Barangay 41 (Rosal)

- Barangay 42 (Pinagbuklod)

- Barangay 42-A (Pinagbuklod A)

- Barangay 42-B (Pinagbuklod B)

- Barangay 42-C (Pinagbuklod C)

- Barangay 43 (Pinagpala)

- Barangay 44 (Maligaya)

- Barangay 45 (Kaunlaran)

- Barangay 45-A (Kaunlaran A)

- Barangay 46 (Sinagtala)

- Barangay 47 (Pagkakaisa)

- Barangay 47-A (Pagkakaisa A)

- Barangay 47-B (Pagkakaisa B)

- Barangay 48 (Narra)

- Barangay 48-A (Narra A)

- Barangay 49 (Akasya)

- Barangay 49-A (Akasya A)

- Barangay 50 (Kabalyero)

- Barangay 51 (Kamagong)

- Barangay 52 (Ipil)

- Barangay 53 (Yakal)

- Barangay 53-A (Yakal A)Air Force

- Barangay 53-B (Yakal B)Navy

- Barangay 54-A (Pechay A)

- Barangay 54-M (Pechay)

- Barangay 55 (Ampalaya)

- Barangay 56 (Labanos)

- Barangay 57 (Repolyo)

- Barangay 58 (Patola)

- Barangay 58-A (Patola A)

- Barangay 59 (Sitaw)

- Barangay 60 (Letsugas)

- Barangay 61 (Talong; Poblacion)

- Barangay 61-A (Talong A; Poblacion)

- Barangay 62 (Kangkong; Poblacion)

- Barangay 62-A (Kangkong A; Poblacion)

- Barangay 62-B (Kangkong B; Poblacion)

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1903 | 16,337 | — |

| 1918 | 22,169 | +2.06% |

| 1939 | 38,254 | +2.63% |

| 1948 | 35,052 | −0.97% |

| 1960 | 54,891 | +3.81% |

| 1970 | 75,739 | +3.27% |

| 1975 | 82,456 | +1.72% |

| 1980 | 87,666 | +1.23% |

| 1990 | 91,641 | +0.44% |

| 1995 | 92,641 | +0.20% |

| 2000 | 99,367 | +1.51% |

| 2007 | 104,581 | +0.71% |

| 2010 | 101,120 | −1.22% |

| 2015 | 102,806 | +0.32% |

| 2020 | 100,674 | −0.41% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[43][44][45][46] | ||

According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 100,674 people,[3] with a density of 9,200 inhabitants per square kilometer or 24,000 inhabitants per square mile.

Religion

editAccording to 2000 census data, Christianity is the most prevalent religion in Cavite City, and a majority of Caviteños practice Roman Catholicism. Other Christian religious groups in the city include the Aglipayan Church, Iglesia ni Cristo (I.N.C), Jehovah's Witnesses, United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP), Jesus Is Lord Church (JIL), The United Methodist Church, Presbyterian Churches, Baptists and Bible Fundamental churches, Seventh-day Adventist Church, Members Church of God International or Ang Dating Daan, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and other UPC churches. A Muslim minority is also present in the city.[47]

Nuestra Señora de la Soledad de Porta Vaga

editThe Nuestra Señora de la Soledad de Porta Vaga (Our Lady of Solitude of Porta Vaga) is viewed as the patroness of Cavite City. She is revered by Catholics as the Celestial Guardian and Protector of the Province of Cavite since her arrival. The image of Our Lady of Porta Vaga is designated as a National Cultural Treasure[48] by the National Museum. It is the oldest existing Marian painting in the Philippines.

The image of the virgin is painted on a canvas. Mary, clothed in black and white like a lady in mourning, kneels as she contemplates the passion of her son. Before her are the crown of thorns and the nails used during the Crucifixion. An inscription was found on the back of the painting – A doze de Abril 1692 años Juan Oliba puso esta Stma. Ymagen Haqui, which means, "The sacred image was placed here by Juan Oliba on April 12, 1692". This particular icon was used to bless the galleons sailing between Cavite and Acapulco (Mexico) during formal sending off ceremonies, and was also called the Patroness of the Galleons.

The image was originally enshrined at the Ermita de Porta Vaga, a small church adjacent to the Porta Vaga Gate, which was destroyed during World War II. The image is presently enshrined at the San Roque Parish Church, one of the three parishes in the city.

Languages

editChabacano is a Spanish-influenced creole language formerly spoken by majority of the people living in the city. Chabacano emerged sometime after the arrival of the first Spaniards and Mexicans in the late 16th century. During this period, the people that lived near the military arsenal in Cavite City communicated with Spaniards and Mexicans and began to incorporate Spanish words into their dialect. Today, a majority of residents speak Tagalog.

Today, Chabacano is generally considered to be dying, with only a fraction of people, mostly elderly, able to speak the language. According to the Philippine professor Alfredo B. German, who wrote a thesis on the grammar of Chabacano, the present conditions do not encourage people to learn the dialect. There are many likely reasons for the diminishing of Chabacano, such as the influx of Tagalog-speaking migrants and intermarriage.

Philippine writer and poet Jesus Balmori expressed himself in Chabacano, and wrote several verses in it. Don Jaime de Veyra, writer and famous Philippine historian, wrote the following lines: "I am afraid that the inevitable absorption of the 'Tagalog invasion' on one side and the 'invasion of the English' on the other hand, will wipe out or extinguish this inherited Castilian language in existence with its last representatives in the following generation." Professor Gervacio Miranda, who also wrote a book in Chabacano, said in his preface: "My only objective to write this book is to possibly conserve in written form the Chabacano of Cavite for posterity," fearing the extinction of the dialect.

Economy

editPoverty incidence of Cavite City

2.5

5

7.5

10

12.5

15

2006

4.70 2009

5.50 2012

5.43 2015

6.94 2018

5.70 2021

12.71 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56] |

Culture

editFestivals and events

editThe city is home to the Annual Cavite City Water Festival or Regada, held from the 17th to the 24th of June. It is a festive and religious celebration of the feast of St. John the Baptist. Regada started in 1996, and features the Paulan or Basayawan, which is a street party where celebrators dance under water sprinklers.[57][58] Another celebration is the Feast for Our Lady of Solitude of Porta Vaga, which is annually observed by local Catholics during every second Sunday of November.[59]

Other notable holidays include the observance of Julián Felipe's birthday (January 28). Felipe, who composed the Philippine National Anthem, was born and raised in Cavite City.[60][61] The city's Charter Day, known locally as simply Cavite City Day, which commemorates the signing of the city charter in 1940, is held every September 7.[62][63]

Cuisine

editFood in Cavite City is influenced by its Spanish heritage combined with Filipino tradition. One popular native dish is bacalao (sauteed codfish), which is served during the Lenten season. A variation of bibingka locally known as bibingkang samala can also be found in the city. This delicacy is made of glutinous rice (malagkit), coconut milk and sugar.[64]

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editThe only road connecting Cavite City to the rest of Luzon is the National Route 62, which begins at P. Burgos Avenue in Caridad district and continues towards Noveleta as the Manila–Cavite Road (not to be confused with Manila-Cavite Expressway).[65] A proposal to construct an expressway from Kawit to Cavite City via Bacoor Bay has been raised to the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH). When realized, the expressway would serve as a link to Manila-Cavite Expressway (CAVITEx).[66][67]

Cavite City has one airport, Danilo Atienza Air Base,[68] located at Sangley Point. The airport is operated by the Philippine Air Force. It was formerly a US Naval Base, called Naval Station Sangley Point, until it was turned over to the Philippine government in 1971.[69] There are proposals to convert the base into a civilian airport, as a solution to the overcrowding of Ninoy Aquino International Airport.[70][71]

As of 2019, no active water-based public transportation services were based in Cavite City.[72] Metrostar Ferry, which began operations in 2007, used to serve trips from San Roque district to Pasay, Metro Manila.[73][74] A new service from the Intramuros district of Manila to the nearby town of Noveleta to the south debuted in January 2018 and is currently the nearest water-based transport to the city.

Utilities

editWater services are currently provided by Maynilad.[75][76] Electric services are currently provided by Meralco.

Symbols

editFlag

editThe flag of the city was created by Mayor Timoteo O. Encarnacion Jr., and was adopted by the Sangguniang Panlungsod through Resolution No. 95-081 dated September 6, 1995, in time for the 55th Cavite City Charter Day. The meaning and significance of the flag components are:

- The two red strips symbolize courage and bravery.

- The middle green strip symbolizes progress and advancement

- The half sun has a twofold meaning. If it is the rising sun, it means hope, dreams, and visions for progress. If it is a setting sun, it stands for the sunset that can be seen from the city's western shores.

- The five yellow stars symbolize the five districts of Cavite City.

- The three sets of waves below the half sun, in three colors of navy blue, light blue and white, signify that Cavite City is a peninsula surrounded by water, while the three colors represent Cañacao Bay, Bacoor Bay, and Manila Bay.

Seal

editThe current seal of the city was designed by Mayor Timoteo O. Encarnacion, Jr. It was adopted by the Sangguniang Panlungsod through Resolution No. 140-90, then approved by the Local Executive on September 7, 1990. On November 3, 1993, the National Historical Institute and the president, through the Department of the Interior and Local Government, issued a Certificate of Registration recognizing the new seal.

The shield stands for bravery and fortitude. The colors red, white, blue, yellow stand for the loyalty of the people to its government. The inclusion of the rays portrays the role of Cavite as one of the original provinces that rose up in arms against Spanish domination in 1896 in the Philippine Revolution.[6]

The white triangle inscribed within the shield with the letters KKK at the corners represents the part played by The city in the organization of the Katipunan. Don Ladislao Diwa of the city was one of the triumvirate who organized the patriotic group. Many Katipuneros came from the city.

Within the white triangle are symbols representing various events:

- At the bottom of the triangle is a fort with figures "1872" symbolizing the Cavite mutiny of 1872 at the Cavite Arsenal.

- At the background is a map of the city including the island of Corregidor representing the role of the island in the city's history.

- The obelisk at the left memorializes the Thirteen Martyrs of Cavite who were executed by the Spaniards on September 12, 1896.

- The sheet music at the right symbolizes Julián Felipe, composer of the Philippine National Anthem who was from the city.

- The fort symbol represents the Royal Fort of San Felipe and its role in the city and country's history, being the place where the "thirteen martyrs of Cavite" were detained and where the Cavite mutiny of 1872 took place.

- The scroll on the uppermost portion of the triangle contains the City motto "Para Dios y Patria" ("For God and Country") in the Chabacano dialect to emphasize the native dialect of the city.

- The green laurel leaf encircling the right and left portions of the KKK triangle symbolizes victories by reason.[6]

Education

editNotable personalities

edit- Nash Aguas

- Herminia Victoriano y Amador

- Eliodoro Ballesteros

- Roman Basa

- Elpidia E. Bonanza

- Purificacion Borromeo

- Ladislao Diwa

- Roman Faustino

- Julián Felipe

- Glaiza Heradura

- Joel Lamangan

- Celeste Legaspi

- Mona Lisa

- Edna Luna

- Lily Marquez

- Raquel Monteza

- Mercedes Matias-Santiago

- Efren Peñaflorida

- Manuel S. Rojas

- Ollie dela Peña

- Olivia Salamanca

- Leopoldo Salcedo

- Rosendo E. Santos Jr.

- Ferdinand Topacio

- Thirteen Martyrs of Cavite

Sister cities

editCavite City has two sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:

- Melilla, Spain

- San Diego, California, United States

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ City of Cavite | (DILG)

- ^ "2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Quezon City, Philippines. August 2016. ISSN 0117-1453. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c Census of Population (2020). "Region IV-A (Calabarzon)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ "PSA Releases the 2021 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. April 2, 2024. Retrieved April 28, 2024.

- ^ Bureau of Insular Affairs (1902). "", pg. 450. Government Printing Office, Washington.

- ^ a b c d e De la Rosa, Joy (2007–09). "About Cavite City". Cavite City Library and Museum. Retrieved on October 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Blair and Robertson (1904). "Philippine Islands 1493–1803, Vol. 12, 1601–1604". pg. 104. Arthu H. Clark Co., Cleveland, OH.

- ^ "Jesuits In The Philippines (1581-1768)" Page 59 "These settlements were much smaller than Manila. In 1582 Manila had an adult male population of 300 Spaniards; Vigan, 60; Nueva Caceres, 30; Cebu, 70; Arevalo, 20. In 1586 Manila had 329 Spanish men and youths capable of bearing arms; the most recently established settlement, Nueva Segovia in Cagayan, had 97; Nueva Caceres, 69; Arevalo, 65; Cavite, 64; Cebu, 63; Villa Fernandina, 19."

- ^ a b c d Muog (January 28, 2008). "el puerto de cavite/ ribera de cavite • cavite city". Muog. Retrieved on 2014-10-29.

- ^ Census Office of the Philippine Islands (1920). "Census of the Philippine Islands 1918, Vol I", pg. 132. Bureau of Printing, Manila.

- ^ Peter Borschberg (2015). Journal, Memorials and Letters of Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge. Security, Diplomacy and Commerce in 17th-Century Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press. pp. 82, 84, 126, 421. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Zamboangueño Chavacano: Philippine Spanish Creole or Filipinized Spanish Creole? By Tyron Judes D. Casumpang (Page 3)

- ^ Convicts or Conquistadores? Spanish Soldiers in the Seventeenth-Century Pacific By Stephanie J. Mawson AGI, México, leg. 25, núm. 62; AGI, Filipinas, leg. 8, ramo 3, núm. 50; leg. 10, ramo 1, núm. 6; leg. 22, ramo 1, núm. 1, fos. 408 r –428 v; núm. 21; leg. 32, núm. 30; leg. 285, núm. 1, fos. 30 r –41 v .

- ^ ESTADISMO DE LAS ISLAS FILIPINAS TOMO PRIMERO By Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga (Original Spanish)

- ^ ESTADISMO DE LAS ISLAS FILIPINAS TOMO SEGUNDO By Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga (Original Spanish)

- ^ Brewster, Sir David (1832). "The Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 15 – Philippine Islands". Joseph and Edward Parker, Philadelphia – Google Books.

- ^ a b Fish, Shirley (2011). "The Manila-Acapulco Galleons: The Treasure Ships of the Pacific". pp. 129–130. AuthorHouse UK, Ltd – Google Books.

- ^ Galaup "Travel Accounts" page 375.

- ^ "Forced Migration in the Spanish Pacific World" By Eva Maria Mehl, page 235.

- ^ (Page 10) Pérez, Marilola (2015). Cavite Chabacano Philippine Creole Spanish: Description and Typology (PDF) (PhD). University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021.

The galleon activities also attracted a great number of Mexican men that arrived from the Mexican Pacific coast as ships' crewmembers (Grant 2009: 230). Mexicans were administrators, priests and soldiers (guachinangos or hombres de pueblo) (Bernal 1964: 188) many though, integrated into the peasant society, even becoming tulisanes 'bandits' who in the late 18th century "infested" Cavite and led peasant revolts (Medina 2002: 66). Meanwhile, in the Spanish garrisons, Spanish was used among administrators and priests. Nonetheless, there is not enough historical information on the social role of these men. In fact some of the few references point to a quick integration into the local society: "los hombres del pueblo, los soldados y marinos, anónimos, olvidados, absorbidos en su totalidad por la población Filipina." (Bernal 1964: 188). In addition to the Manila-Acapulco galleon, a complex commercial maritime system circulated European and Asian commodities including slaves. During the 17th century, Portuguese vessels traded with the ports of Manila and Cavite, even after the prohibition of 1644 (Seijas 2008: 21). Crucially, the commercial activities included the smuggling and trade of slaves: "from the Moluccas, and Malacca, and India… with the monsoon winds" carrying "clove spice, cinnamon, and pepper and black slaves, and Kafir [slaves]" (Antonio de Morga cf Seijas 2008: 21)." Though there is no data on the numbers of slaves in Cavite, the numbers in Manila suggest a significant fraction of the population had been brought in as slaves by the Portuguese vessels. By 1621, slaves in Manila numbered 1,970 out of a population of 6,110. This influx of slaves continued until late in the 17th century; according to contemporary cargo records in 1690, 200 slaves departed from Malacca to Manila (Seijas 2008: 21). Different ethnicities were favored for different labor; Africans were brought to work on the agricultural production, and skilled slaves from India served as caulkers and carpenters.

- ^ The Philippines Glimpsed in the First Latin-American "Novel" By James S. Cummins

- ^ "Philippines is Not Only Manila". Discovering Philippines. Retrieved on October 30, 2014.

- ^ "". Muog. Retrieved on October 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Tewell, John (January 29, 2011). "Cavite, Luzon Island, Philippines 1945". Flickr. Retrieved on 2014-10-20.

- ^ a b Balbosa, Joven Zamoras (1992). "IMF Stabilization Program and Economic Growth: The Case of the Philippines" (PDF). Journal of Philippine Development. XIX (35). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ Balisacan, A. M.; Hill, Hal (2003). The Philippine Economy: Development, Policies, and Challenges. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195158984.

- ^ Cororaton, Cesar B. "Exchange Rate Movements in the Philippines". DPIDS Discussion Paper Series 97-05: 3, 19.

- ^ Kessler, Richard J. (1989). Rebellion and repression in the Philippines. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300044062. OCLC 19266663.

- ^ Celoza, Albert F. (1997). Ferdinand Marcos and the Philippines: The Political Economy of Authoritarianism. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275941376.

- ^ Schirmer, Daniel B. (1987). The Philippines reader : a history of colonialism, neocolonialism, dictatorship, and resistance (1st ed.). Boston: South End Press. ISBN 0896082768. OCLC 14214735.

- ^ a b c Magno, Alexander R., ed. (1998). "Democracy at the Crossroads". Kasaysayan, The Story of the Filipino People Volume 9:A Nation Reborn. Hong Kong: Asia Publishing Company Limited.

- ^ "THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs. JACINTO REYES y RAMIREZ and OSCAR SABATER". The LawPhil Project. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Philippines martial law: The fight to remember a decade of arrests and torture". BBC News. September 28, 2022.

- ^ a b "ALVAREZ, Emmanuel I".

- ^ "A Path to Democratic Renewal" (PDF). USAid. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ editor, loreben tuquero (February 15, 2020). "Duterte inaugurates Sangley Airport". RAPPLER. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Publisher, Web (February 14, 2020). "Sole bidder awarded P208B Sangley Point airport project". PortCalls Asia. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ Camus, Miguel R. (January 28, 2021). "Cavite drops China-backed Sangley airport deal". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ News, TED CORDERO, GMA (August 23, 2022). "Cavitex-Yuchengco-led consortium set to bag Sangley airport project on Sept. 15". GMA News Online. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Sangley Point Cavite Climatological Normal Values" (PDF). Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ "Sangley Point Cavite Climatological Extremes" (PDF). Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ "Philippine Standard Geographic Code listing for Cavite City". Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Census of Population (2015). "Region IV-A (Calabarzon)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ Census of Population and Housing (2010). "Region IV-A (Calabarzon)" (PDF). Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. National Statistics Office. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ Censuses of Population (1903–2007). "Region IV-A (Calabarzon)". Table 1. Population Enumerated in Various Censuses by Province/Highly Urbanized City: 1903 to 2007. National Statistics Office.

- ^ "Province of Cavite". Municipality Population Data. Local Water Utilities Administration Research Division. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ "2000 Census of Population and Housing - Cavite" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. January 2003. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ Hermoso, Christina (August 8, 2023). "Our Lady Soledad de Porta Vaga replica image on display at Radio Veritas". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on November 30, 2023. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ "Poverty incidence (PI):". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. November 29, 2005.

- ^ "2003 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. March 23, 2009.

- ^ "City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates; 2006 and 2009" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. August 3, 2012.

- ^ "2012 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. May 31, 2016.

- ^ "Municipal and City Level Small Area Poverty Estimates; 2009, 2012 and 2015". Philippine Statistics Authority. July 10, 2019.

- ^ "PSA Releases the 2018 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. December 15, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2022.

- ^ "PSA Releases the 2021 City and Municipal Level Poverty Estimates". Philippine Statistics Authority. April 2, 2024. Retrieved April 28, 2024.

- ^ "Regada Festival". The Official Website of the Province of Cavite. February 27, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ "Cavite folks water party on St. John the Baptist feast day". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ Darang, Josephine. "Asian Catholics coming to Manila for Cardinal Tagle's new evangelization confab at UST; Cavite to hold 'Soledad' fiesta". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "The birth of the Philippine National Anthem". The Philippine Star. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "Julian Felipe was born in Cavite City January 28, 1861". The Kahimyang Project. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ Placido, Dharel. "LIST: Duterte OKs more holidays around PH". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ "Palace declares Sept. 7 non-working holiday in Cavite City". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "Cavite cuisine is waiting to be discovered". CNN Philippines. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ "MVP's Metro Pacific proposes Sangley-Cavitex expressway". Rappler. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ "MPIC proposes Cavitex-Sangley expressway". Manila Standard. August 6, 2017. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ "Manila-Sangley Point Danilo Atienza Air Base Profile | CAPA". centreforaviation.com. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "Philippine Air Force: Official Website". www.paf.mil.ph. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "Airports plan in full swing, but new international gateway uncertain". BusinessMirror. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ Camus, Miguel R. "Cavite LGU pushes $9.3-B Sangley airport project". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ Cruz, Neal H. "Let's use more ferryboats and trains". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "SM Prime Holdings |". www.smprime.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "The Manila Times – Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "Maynilad offers free septic tank cleaning". The Manila Times. November 4, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ Cabalza, Dexter. "Leak repaired but still no water supply in southern NCR, Cavite – Maynilad". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

External links

edit- Media related to Cavite City at Wikimedia Commons

- Cavite City travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Official Cavite City Government website

- Official Website of the Cavite City Library and Museum

- Philippine Standard Geographic Code

- Philippine Census Information