This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

A deprivation index or poverty index (or index of deprivation or index of poverty) is a data set to measure relative deprivation (a measure of poverty) of small areas. Such indices are used in spatial epidemiology to identify socio-economic confounding.

History

editIn 1983, Brian Jarman published the Jarman Index, also known as the Underprivileged Area Score, to identify underprivileged areas.[1][2] Since then, many other indices have been developed.

Australia

edit"Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 27 March 2018.

Canada

editStatistics Canada publishes the Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation.[3]

China

editChina's county-level area deprivation index (CADI) [4]

Europe

editEuropean Deprivation Index

editThe European Deprivation Index was published by Launoy et al in 2018 with a goal of addressing social inequalities in health.[5]

Laeken indicators

editThe Laeken indicators is a set of common European statistical indicators on poverty and social exclusion, established at the European Council of December 2001 in the Brussels quarter of Laeken, Belgium. They were developed as part of the Lisbon Strategy, of the previous year, which envisioned the coordination of European social policies at country level based on a set of common goals.[6]

Laeken indicators include the following.

- At-risk-of-poverty rate

- At-risk-of-poverty threshold

- S80/S20 income quintile share ratio

- Persistent at-risk-of-poverty rate

- Persistent at-risk-of-poverty rate (alternative threshold)

- Relative median at-risk-of-poverty gap

- Regional cohesion

- Long-term unemployment rate

- Persons living in jobless households

- Early school leavers not in education or training

- Life expectancy at birth

- Self defined health status

- Dispersion around the at-risk-of-poverty threshold

- At-risk-of-poverty rate anchored at one moment in time

- At-risk-of-poverty rate before cash social transfers

- Gini coefficient

- In-work at risk of poverty rate

- Long term unemployment share

- Very long term unemployment rate

Most of these indicators are discriminated by various criteria (gender, age group, household type, etc.).

France

edit"Indice de défavorisation social" [The FDEP, The French DEPrivation index]. AtlaSanté (in French).

Germany

editThe German Index of Multiple Deprivation (GIMD) [7]

Italy

editThe Italian deprivation index [8]

United Kingdom

editIndices of Multiple Deprivation

editIndices of multiple deprivation (IMD) are datasets used within the UK to classify the relative deprivation (a measure of poverty) of small areas. Multiple components of deprivation are weighted with different strengths and compiled into a single score of deprivation. Small areas are then ranked by deprivation score. As such, deprivation scores must be treated as an ordinal variable.

They are created by the British Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). The principle behind the index is to target government action in the areas which need it most.

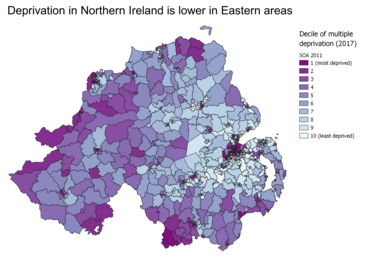

The calculation and publication of the indices is devolved and indices of multiple deprivation for Wales, Scotland, England, and Northern Ireland are calculated separately. While the components of deprivation that make up the overall deprivation score are similar in all four nations of the UK the weights assigned to each component, the size of the geographies for which deprivation scores are calculated, and the years of calculation are different. As a result levels of deprivation cannot be easily compared between nations.

The geography at which IMDs are produced varies across the nations of the UK and has varied over time. Currently the smallest geography for which IMDs are published is LSOA level in both England and Wales, data zone level for Scotland, and Super Output Area (SOA) for Northern Ireland. Early versions of the English IMDs were published at electoral ward and English local authority level.

The use of IMDs in social analysis aims to balance the desire for a single number describing the concept of deprivation in a place and the recognition that deprivation has many interacting components. IMDs may be an improvement over simpler measures of deprivation such as low average household disposable income because they capture variables such as the advantage of access to a good school and the disadvantage of exposure to high levels of air pollution. A potential disadvantage is that the choice of components and the weighting of those components in the construction of the overall multiple deprivation score is unavoidably subjective.

Using an IMD to assess outcomes with a deprivation gradient may introduce circularity or endogeneity bias if the outcome overlaps with an IMD indicator. For instance, standardised mortality rates, which show a deprivation gradient, contribute to the health domain of the Scottish IMD. While evidence suggests minimal impact on inequalities research, researchers often use only the income domain to avoid this bias.[9]

Cases for indexes of multiple deprivation at larger and smaller geographies

editIMDs are calculated separately for England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland and are not comparable across them. While the geographies, the input measures, and the weights assigned to each input measure are different in all four countries, they are similar enough to calculate a combined UK IMD with only small sacrifices in data quality. Decisions within the UK that are taken nationally would be usefully informed by a UK index of multiple deprivation and this work has been proven possible and performed.[10] The most recent whole-UK index of multiple deprivation was compiled by MySociety in 2021.[11]

There are also examples of IMDs being created for smaller geographies within nations. This is particularly important in places with very high deprivation in almost all areas. For example, using English IMDs in Manchester is not useful for targeting local interventions since over half of the city is classed as being in England's most deprived decile. By using raw deprivation scores for small areas within the area of interest before they are ranked at the national level, a local IMD can be calculated showing relative deprivation within a place instead of its relative deprivation within England.

Applicability of IMDs to the analysis of very diverse areas

editIMDs are the property of a small area and represent the average characteristics of the people living in that area. They are not the property of any single person living within the area. Research has demonstrated IMDs have low sensitivity and specificity for detecting income- and employment-deprived individuals.[12] Failure by researchers to consider this can lead to misleading features in analysis based on IMDs. This is a particularly large risk in areas which are very diverse due to social housing and mixed community policies such as central London. In these settings, a mixed community with a mix of very low income families in poor health and very high income families in good health can return a middling IMD score that represents neither group well and fails to provide useful insight to users of analysis based on IMD data. Other groups not well represented by IMDs are mobile communities and people experiencing homelessness, some of the most deprived members of society.[13]

National indices

editResponsibility for the production of publication of IMDs varies by the nation that they cover. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) publishes IMDs for Northern Ireland. StatsWales publishes IMDs for Wales. The Scottish Government publishes IMDs for Scotland. The UK Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) publishes IMDs for England.

Early version of English IMDs were produced by the Social Disadvantage Research Group at the University of Oxford.

The most recent IMDs for the four nations of the UK are,

- Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure 2017 (NIMDM2017).

- English Indices of Deprivation 2019.

- Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) 2020.

- Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) 2019.

Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

editThe Scottish index of multiple deprivation (SIMD) is used by local authorities, the Scottish government, the NHS and other government bodies in Scotland to support policy and decision making. It won the Royal Statistical Society's Excellence in Official Statistics Awards in 2017.[14][15][16][17][18][19]

The SIMD 2020 is composed of 43 indicators grouped into seven domains of varying weight: income, employment, health, education, skills and training, housing, geographic access and crime.[20] These seven domains are calculated and weighted for 6,976 small areas, called ‘data zones’, with roughly equal population. With the population total at 5.3 million that comes to an average population of 760 people per data zone.[21][22]

1983: Jarman Index, Underprivileged Area Score

editIn 1983, Brian Jarman published the Underprivileged Area Score, which became known as the Jarman Index. This measured socio-economic variation across small geographical areas.[23][24] The score is an outcome of the need identified in the Acheson Committee Report (into General Practitioner (GP) services in the UK) to create an index to identify 'underprivileged areas' where there were high numbers of patients and hence pressure on general practitioner services.

Its creation involved the random distribution of a questionnaire among general practitioners throughout the UK. This was then used to obtain statistical weights for a calculation of a composite index of underprivileged areas based on GPs' perceptions of workload and patient need.

1988: Townsend Deprivation Index

editThe Townsend index is a measure of material deprivation within a population. It was first described by sociologist Peter Townsend in 1988.[25]

The measure incorporates four variables:

- Unemployment (as a percentage of those aged 16 and over who are economically active);

- Non-car ownership (as a percentage of all households);

- Non-home ownership (as a percentage of all households); and

- Household overcrowding.

These variables can be measured for the population of a given area and combined (via a series of calculations involving log transformations and standardisations) to give a “Townsend score” for that area.[26] A greater Townsend index score implies a greater degree of deprivation. Areas may be “ranked” according to their Townsend score as a means of expressing relative deprivation.

A Townsend score can be calculated for any area where information is available for the four index variables. Commonly, census data are used and scores are calculated at the level of census output areas.[27] Scores for these areas may be linked or mapped to other geographical areas, such as postcodes, to make the scores more applicable in practice. The Townsend index has been the favoured deprivation measure among UK health authorities.[28]

Researchers at the University of Bristol's eponymous “Townsend Centre for International Poverty Research” continue to work on “meaningful measures of poverty”.[29]

1991: Carstairs Index

editThe Carstairs index was developed by Vera Carstairs and Russell Morris, and published in 1991 as Deprivation and Health in Scotland.[30] The work focuses on Scotland, and was an alternative to the Townsend Index to avoid the use of households as denominators.[31] The Carstairs index is based on four Census variables: low social class, lack of car ownership, overcrowding and male unemployment and the overall index reflects the material deprivation of an area, in relation to the rest of Scotland. Carstairs indices are calculated at the postcode sector level, with average population sizes of approximately 5,000 persons.

The Carstairs index makes use of data collected at the Census to calculate the relative deprivation of an area, therefore there have been four versions: 1981, 1991, 2001 and 2011. The Carstairs indices are routinely produced and published[32] by the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit at the University of Glasgow.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Male unemployment | The proportion of economically active males seeking or waiting to start work. |

| Lack of car ownership | The proportion of all persons in private households which do not own a car. |

| Overcrowding | The proportion of all persons living in private households with a density of more than one person per room |

| Low social class | The proportion of all persons in private households with an economically active head of household in social class IV or V |

Methodology

editThe components of the Carstairs score are unweighted, and so to ensure that they all have equal influence over the final score, each variable is standardised to have a population-weighted mean of zero, and a variance of one, using the z-score method.[30] The Carstairs index for each area is the sum of the standardised values of the components. Indices may be positive or negative, with negative scores indicating that the area has a lower level of deprivation, and positive scores suggesting the area has a relatively higher level of deprivation.[citation needed]

The indices are typically ordered from lowest to highest, and grouped into population quintiles. In the 1981, 1991 and 2001 indices, quintile 1 represented the least [33] deprived areas, and quintile 5 represented the most deprived. In 2011, the order was reversed, in line with the ordering of the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.[34]

Changes to the variables

editThe low social class component of the 1981 and 1991 Carstairs index was created using the Registrar General's Social Class (later Social Class for Occupation). In 2001, this was superseded by the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC). This meant that the definition of low social class had to be amended to reflect the approximate operational categories.[35] The definition of overcrowding was amended between 1981 and 1991, due to the inclusion of kitchens of at least 2 metres wide into the room count in the census.[36]

Index of Multiple Deprivation 2000

editThe Index of Multiple Deprivation 2000 (IMD 2000) showed relative levels of social and economic deprivation across all the counties of England at a ward level, the first national study of its kind. [citation needed]

Deprivation across the 8414 wards in the country was assessed, using the criteria of income, employment, health, education, housing, access, and child poverty.[37]

Wards ranking in the most deprived 10 per cent in the country were earmarked for additional funding and assistance.

The most deprived wards in England were found to be Benchill in Manchester, Speke in Liverpool, Thorntree in Middlesbrough, Everton in Liverpool, and Pallister in Middlesbrough.[37]

Indices of Deprivation 2004

editIMD2000 was the subject of some controversy,[citation needed] and was succeeded by the Indices of Deprivation 2004 (ID 2004) which abandoned ward-level data and sampled much smaller geographical areas.[38][39][40][41]

It is unusual in its inclusion of a measure of geographical access as an element of deprivation and in its direct measure of poverty (through data on benefit receipts). The ID 2004 is based on the idea of distinct dimensions of deprivation which can be recognised and measured separately. These are then combined into a single overall measure. The Index is made up of seven distinct dimensions of deprivation called Domain Indices. Whilst it is known as the ID2004, most of the data actually dates from 2001.

The Indices of deprivation 2004 are measured at the Lower Layer Super Output Area level. Super Output Areas were developed by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) from the Census 2001 Output Areas. There are two levels, the lowest (which the Index is based upon) being smaller than wards and containing a minimum of 1,000 people and 400 households. The middle layer contains a minimum of 5,000 people and 2,000 households. Earlier proposals to introduce Upper Layer Super Output Areas were dropped due to lack of demand.

In addition to Super Output Areas, Summaries of the ID 2004 are presented at District level, County level and Primary Care Trust (PCT) level.

While each SOA is of higher resolution than the highest resolution ward index data of the IMD2000 and therefore better at identifying "pockets" of deprivation within wards the 2004 system has its problems. Some areas of deprivation can still be hidden because of the size of SOAs. Examples of this can be found by comparing central areas of Keighley using the Bradford District Deprivation Index (developed by Bradford Council produced at 1991 Census Enumeration District level) with the ID2004. Additionally SOAs were tasked with providing complete coverage of England and Wales – this combined with the minimum population and household counts within each SOA means that large areas of agricultural, commercial and industrial land have to be included within a residential area that borders them – thus when some very deprived residential areas are mapped, a large area of supposed deprivation emerges, however most of it may not be so but rather has a wide area of relative affluence around it – these can appear to be a greater problem than many smaller completely residential SOAs in which higher concentrations of deprived people live but mixed with more affluent neighbours.

Indices of Deprivation 2007

editThe Indices of Deprivation 2007 (ID 2007) is a deprivation index at the small area level was released on 12 June 2007. It follows the ID2004 and because much of the datasets are the same or similar between indices, it allows for a comparison of 'relative deprivation' of an area between the two indices.[42]

While it is known as the ID2007, most of the data actually dates from 2005, and most of the data for the ID2004 was from 2001.

The new Index of Multiple Deprivation 2007 (IMD 2007) is a Lower layer Super Output Area (LSOA) level measure of multiple deprivation, and is made up of seven LSOA level domain indices. There are also two supplementary indices (Income Deprivation Affecting Children and Income Deprivation Affecting Older People). Summary measures of the IMD 2007 are presented at local authority district level and county council level. The LSOA level Domain Indices and IMD 2007, together with the local authority district and county summaries are referred to as the Indices of Deprivation 2007 (ID 2007).(Rusty 2009)

The ID 2007 are based on the approach, structure and methodology that were used to create the previous ID 2004. The ID 2007 updates the ID 2004 using more up-to-date data. The new IMD 2007 contains seven domains which relate to income deprivation, employment deprivation, health deprivation and disability, education skills and training deprivation, barriers to housing and services, living environment deprivation, and crime.

Like the ID2004 it is unusual in that it includes a measure of geographical access as an element of deprivation and its direct measure of poverty (through data on benefit receipts). The ID 2007 is based on the idea of distinct dimensions of deprivation which can be recognised and measured separately. These are then combined into a single overall measure. The Index is made up of seven distinct dimensions of deprivation called Domain Indices, which are: income; employment; health and disability, education, skills, and training; barriers to housing and services; living environment; and crime.

Like the ID2004, the ID2007 are measured at Lower Layer Super Output Areas and have similar strengths and weakness regarding concentrated pockets of deprivation. In addition to Super Output Areas, summary measures of the ID2007 are presented at district level, county level and Primary Care Trust (PCT) level.

Indices of Deprivation 2010

editThe Indices of Deprivation 2010 (ID 2010) was released on 24 March 2011. It follows the ID2007 and because much of the datasets are the same or similar between indices allows a comparison of "relative deprivation" of an area between the two indices.[43]

While it is known as the ID2010, most of the data actually dates from 2008.

The ID 2010 found that 5 million people lived in the most deprived areas in England in 2008 and 38 per cent of them were income deprived. The most deprived area in the country is in the village of Jaywick on the Essex coast. The local authorities with the highest proportion of lower layer Super Output Areas (LSOAs) were in Liverpool, Middlesbrough, Manchester, Knowsley, the City of Kingston upon Hull, Hackney and Tower Hamlets. 98% of the most deprived LSOAs are in urban areas but there are also pockets of deprivation across rural areas. 56% of local authorities contain at least one LSOA amongst the 10 per cent most deprived in England. 88% of the LSOAs that are the most deprived in 2010 were also amongst the most deprived in 2007.

Indices of Deprivation 2019

editThe Indices of Deprivation 2019 (ID 2019) was published in September 2019.[44] It has seven domains of deprivation: income, employment, education, health, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment.

These domains each have multiple components. For example the Barriers to Housing and Services considers seven components including levels of household overcrowding, homelessness, housing affordability, and the distance by road to four types of key amenity (post office, primary school, supermarket, and GP surgery).

Department of Environment Index

editThe Department of Environment Index (DoE) is an index of urban poverty published by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and designed to assess relative levels of deprivation in local authorities in England.[45] The DoE has three dimensions of deprivation: social, economic and housing.

United States

edit- The Area Deprivation Index (ADI).[46][47] US Department of Health and Human Services. September 2022, developed by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration. The index is currently being used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to adjust financial benchmarks in various Value-based health care models.[48] However, some researchers have pointed out that applying ADI in practice has several limitations.[49][50]

- Social Deprivation Index[51][52] by the American Academy of Family Physicians

- Social Vulnerability Index[53] by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Switzerland

editReferences

edit- ^ "Jarman index". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 2024-12-01.

- ^ Jarman, B. (1983-05-28). "Identification of underprivileged areas". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.). 286 (6379): 1705–1709. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6379.1705. ISSN 0267-0623. PMC 1548179. PMID 6405943.

- ^ "The Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation". The Government of Canada. 12 June 2019.

- ^ Wang Z, Chan KY, Poon AN, et al. (2021). "Construction of an area-deprivation index for 2869 counties in China: a census-based approach" (PDF). J Epidemiol Community Health. 75 (2): 114–119. doi:10.1136/jech-2020-214198. hdl:20.500.11820/b76c5efe-f4a2-4be2-bcbc-01ec5f34da47. PMID 33037046. S2CID 222256479.

- ^ Launoy G, Launay L, Dejardin O, Bryère J, Guillaume E (November 2018). "European Deprivation Index: designed to tackle socioeconomic inequalities in cancer in Europe". European Journal of Public Health. 28 (suppl_4): cky213-625. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky213.625.

- ^ Marlier, Eric (2007). The EU and social inclusion: facing the challenges. The Policy Press. pp. 46–53. ISBN 978-1-86134-884-5.

- ^ Maier W (2017). "[Indizes Multipler Deprivation zur Analyse regionaler Gesundheitsunterschiede in Deutschland : Erfahrungen aus Epidemiologie und Versorgungsforschung][Article in German]". Bundesgesundheitsblatt – Gesundheitsforschung – Gesundheitsschutz. 60 (12): 1403–12. doi:10.1007/s00103-017-2646-2. PMID 29119206.

- ^ Rosano A, Pacelli B, Zengarini N, Costa G, Cislaghi C, Caranci N (2020). "[Aggiornamento e revisione dell'indice di deprivazione italiano 2011 a livello di sezione di censimento][Article in Italian]". Epidemiol Prev. 44 (2–3): 162–70. doi:10.19191/EP20.2-3.P162.039. PMID 32631016.

- ^ Bradford, D.R.R.; Allik, M.; McMahon, A.D.; Brown, D. (March 2023). "Assessing the risk of endogeneity bias in health and mortality inequalities research using composite measures of multiple deprivation which include health-related indicators: A case study using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation and population health and mortality data". Health & Place. 80: 102998. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2023.102998.

- ^ Abel GA, Barclay ME, Payne RA (November 2016). "Adjusted indices of multiple deprivation to enable comparisons within and between constituent countries of the UK including an illustration using mortality rates". BMJ Open. 6 (11): e012750. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012750. PMC 5128942. PMID 27852716.

- ^ "Unified UK measures of rurality and deprivation". mySociety. 2021-04-22. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ McCartney, G.; Hoggett, R.; Walsh, D.; Lee, D. (April 2023). "How well do area-based deprivation indices identify income- and employment-deprived individuals across Great Britain today?". Public Health. 217: 22–25. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2023.01.020.

- ^ Moscrop A, Ziebland S, Bloch G, Iraola JR (24 November 2020). "If social determinants of health are so important, shouldn't we ask patients about them?". BMJ. 371: m4150. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4150. PMID 33234506. S2CID 227128683.

- ^ Excellence in Official Statistics Awards: winner announced. Royal Statistical Society. 2017. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- ^ Bradley, Jane (31 August 2016). "Scotland's most deprived areas revealed". The Scotsman. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Behan, Paul (5 September 2016). "Report paints bleak picture of rising poverty levels in Dumbarton and the Vale". Dumbarton Reporter. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation on the Scottish Government website

- ^ Deprivation in Scotland 2012, Google Maps overlaid with SIMD12 data by Professor Alasdair Rae of the University of Sheffield

- ^ Official stats, and how to publish them – a post with Taylor Swift, blog post by Dr. Peter Matthews of the University of Stirling

- ^ Ralston, Kevin; Dundas, Ruth; Leyland, Alastair H (8 July 2014). "A comparison of the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) 2004 with the 2009 + 1 SIMD: does choice of measure affect the interpretation of inequality in mortality?". International Journal of Health Geographics. 13 (27): 27. doi:10.1186/1476-072X-13-27. PMC 4105786. PMID 25001866.

- ^ Introducing The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2016 (PDF). Scottish Government. 31 August 2016. ISBN 978-1-78652-417-1. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ^ SIMD16 Technical Notes (PDF). Scottish Government. 2016. Retrieved 2017-12-19. This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0. © Crown copyright.

- ^ Jarman, B. (1983) Identification of underprivileged areas. British Medical Journal 1705 – 1709

- ^ Elliott P, Cuzick J, English D, Stern R. (2001) Geographical and Environmental Epidemiology. Methods for Small-Area Studies. Oxford University Press. New York,

- ^ Townsend, P., Phillimore, P. and Beattie, A. (1988) Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North. Routledge, London.

- ^ National Centre for Research Methods. Geographical Referencing Learning Resources. http://www.restore.ac.uk/geo-refer/36229dtuks00y19810000.php

- ^ Warwickshire County Council. Warwickshire COAs – Deprivation & Disadvantage Based on the Townsend Index. http://www.warwickshire.gov.uk/observatory/observatorywcc.nsf/0/449B59A1C7151A9E802572CF0038641E/$file/Intro%20&%20CTY.pdf

- ^ Central and Local Information Partnership. Measuring deprivation. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ University of Bristol. Townsend Centre for International Poverty Research. http://www.bristol.ac.uk/poverty/definingandmeasuringpoverty.html

- ^ a b Carstairs, V.; Morris, R. (1991). Deprivation and Health in Scotland. Aberdeen University Press.

- ^ Elliott P, Cuzick J, English D, Stern R. Geographical and Environmental Epidemiology. Methods for Small-Area Studies. Oxford University Press. New York, 1997

- ^ "University of Glasgow – Research Institutes – Institute of Health & Wellbeing – Research – MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit – Research programmes – Measurement and Analysis of Socio-economic Inequalities in Health – Carstairs scores". April 26, 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-04-26.

- ^ "Health stats" (PDF). www.ons.gov.uk. 2006. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- ^ Brown, D., Allik, M., Dundas, R. and Leyland, A. H. (2014) Carstairs Scores for Scottish Postcode Sectors, Datazones and Output Areas from the 2011 Census. Technical Report. MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/99555/

- ^ McLoone, P. (2004) Carstairs scores for Scottish Postcode sectors from the 2001 Census. MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow

- ^ McLoone, P. (1994) Carstairs Scores for Scottish Postcode Sectors from the 1991 Census. Public Health Research Unit, University of Glasgow http://www.sphsu.mrc.ac.uk/files/File/library/other%20reports/Carstairs.pdf Archived 2009-11-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Indices of deprivation 2000". Archived from the original on November 25, 2007.

- ^ Indices of deprivation 2007

- ^ Indices of deprivation 2004

- ^ Indices of Multiple Deprivation 2000 AKA Indices of Deprivation 2000

- ^ Bradford District Deprivation Index

- ^ See "Using the English Indices of Deprivation 2007: Guidance Archived 2008-11-25 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ See http://www.communities.gov.uk/publications/corporate/statistics/indices2010?view=Standard Archived 2012-04-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ English Indices of Deprivation 2019 (IoD2019)

- ^ Elliott P, Cuzick J, English D, Stern R. Geographical and Environmental Epidemiology: Methods for Small-Area Studies. Oxford University Press. New York, 1997

- ^ "Neighborhood Atlas – Home". www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ "Landscape of Area-Level Deprivation Measures and Other Approaches to Account for Social Risk and Social Determinants of Health in Health Care Payments". ASPE. 26 September 2022. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ^ "Embedding Equity In Financial Benchmarks: Changes To The Health Equity Benchmark Adjustment". Health Affairs. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ "A Proposal to Enhance the Health Equity Benchmark Adjustment in ACO REACH". CareJourney Research Blog Article by Yubin Park, Aneesh Chopra et al. 16 September 2022. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ "Problem with the University of Wisconsin's Area Deprivation Index. And, no, face validity is not "the weakest of all possible arguments." by Andrew Gelman". Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ "Social Deprivation Index(SDI)". ASPE. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ Butler D, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A (2013). "Measures of social deprivation that predict health care access and need within a rational area of primary care service delivery". Health Serv. Res. 48 (2): 539–559. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01449.x. PMC 3626349. PMID 22816561.

- ^ "CDC/ASTDR Social Vulnerability Index". ASPE. 21 May 2024. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ Panczak R, Galobardes B, Voorpostel M, Spoerri A, Zwahlen M, Egger M (2012). "A Swiss neighbourhood index of socioeconomic position: development and association with mortality". J Epidemiol Community Health. 66 (12): 1129–36. doi:10.1136/jech-2011-200699. PMC 5204371. PMID 22717282.

- ^ Panczak R, Berlin C, Voorpostel M, Zwahlen M, Egger M (2023). "The Swiss neighbourhood index of socioeconomic position: update and re-validation". Swiss Med Wkly. 153 (1): 40028. doi:10.57187/smw.2023.40028. PMID 36652707. S2CID 255922171.