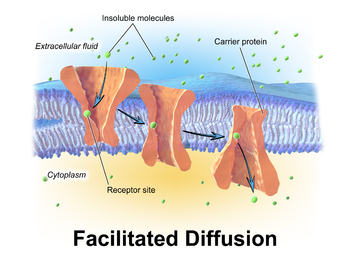

Facilitated diffusion (also known as facilitated transport or passive-mediated transport) is the process of spontaneous passive transport (as opposed to active transport) of molecules or ions across a biological membrane via specific transmembrane integral proteins.[1] Being passive, facilitated transport does not directly require chemical energy from ATP hydrolysis in the transport step itself; rather, molecules and ions move down their concentration gradient according to the principles of diffusion.

Facilitated diffusion differs from simple diffusion in several ways:

- The transport relies on molecular binding between the cargo and the membrane-embedded channel or carrier protein.

- The rate of facilitated diffusion is saturable with respect to the concentration difference between the two phases; unlike free diffusion which is linear in the concentration difference.

- The temperature dependence of facilitated transport is substantially different due to the presence of an activated binding event, as compared to free diffusion where the dependence on temperature is mild.[2]

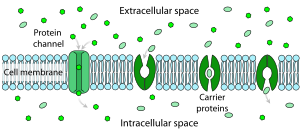

Polar molecules and large ions dissolved in water cannot diffuse freely across the plasma membrane due to the hydrophobic nature of the fatty acid tails of the phospholipids that comprise the lipid bilayer. Only small, non-polar molecules, such as oxygen and carbon dioxide, can diffuse easily across the membrane. Hence, small polar molecules are transported by proteins in the form of transmembrane channels. These channels are gated, meaning that they open and close, and thus deregulate the flow of ions or small polar molecules across membranes, sometimes against the osmotic gradient. Larger molecules are transported by transmembrane carrier proteins, such as permeases, that change their conformation as the molecules are carried across (e.g. glucose or amino acids). Non-polar molecules, such as retinol or lipids, are poorly soluble in water. They are transported through aqueous compartments of cells or through extracellular space by water-soluble carriers (e.g. retinol binding protein). The metabolites are not altered because no energy is required for facilitated diffusion. Only permease changes its shape in order to transport metabolites. The form of transport through a cell membrane in which a metabolite is modified is called group translocation transportation.

Glucose, sodium ions, and chloride ions are just a few examples of molecules and ions that must efficiently cross the plasma membrane but to which the lipid bilayer of the membrane is virtually impermeable. Their transport must therefore be "facilitated" by proteins that span the membrane and provide an alternative route or bypass mechanism. Some examples of proteins that mediate this process are glucose transporters, organic cation transport proteins, urea transporter, monocarboxylate transporter 8 and monocarboxylate transporter 10.

In vivo model of facilitated diffusion

editMany physical and biochemical processes are regulated by diffusion.[3] Facilitated diffusion is one form of diffusion and it is important in several metabolic processes. Facilitated diffusion is the main mechanism behind the binding of Transcription Factors (TFs) to designated target sites on the DNA molecule. The in vitro model, which is a very well known method of facilitated diffusion, that takes place outside of a living cell, explains the 3-dimensional pattern of diffusion in the cytosol and the 1-dimensional diffusion along the DNA contour.[4] After carrying out extensive research on processes occurring out of the cell, this mechanism was generally accepted but there was a need to verify that this mechanism could take place in vivo or inside of living cells. Bauer & Metzler (2013)[4] therefore carried out an experiment using a bacterial genome in which they investigated the average time for TF – DNA binding to occur. After analyzing the process for the time it takes for TF's to diffuse across the contour and cytoplasm of the bacteria's DNA, it was concluded that in vitro and in vivo are similar in that the association and dissociation rates of TF's to and from the DNA are similar in both. Also, on the DNA contour, the motion is slower and target sites are easy to localize while in the cytoplasm, the motion is faster but the TF's are not sensitive to their targets and so binding is restricted.

Intracellular facilitated diffusion

editSingle-molecule imaging is an imaging technique which provides an ideal resolution necessary for the study of the Transcription factor binding mechanism in living cells.[5] In prokaryotic bacteria cells such as E. coli, facilitated diffusion is required in order for regulatory proteins to locate and bind to target sites on DNA base pairs.[3][5][6] There are 2 main steps involved: the protein binds to a non-specific site on the DNA and then it diffuses along the DNA chain until it locates a target site, a process referred to as sliding.[3] According to Brackley et al. (2013), during the process of protein sliding, the protein searches the entire length of the DNA chain using 3-D and 1-D diffusion patterns. During 3-D diffusion, the high incidence of Crowder proteins creates an osmotic pressure which brings searcher proteins (e.g. Lac Repressor) closer to the DNA to increase their attraction and enable them to bind, as well as steric effect which exclude the Crowder proteins from this region (Lac operator region). Blocker proteins participate in 1-D diffusion only i.e. bind to and diffuse along the DNA contour and not in the cytosol.

Facilitated diffusion of proteins on chromatin

editThe in vivo model mentioned above clearly explains 3-D and 1-D diffusion along the DNA strand and the binding of proteins to target sites on the chain. Just like prokaryotic cells, in eukaryotes, facilitated diffusion occurs in the nucleoplasm on chromatin filaments, accounted for by the switching dynamics of a protein when it is either bound to a chromatin thread or when freely diffusing in the nucleoplasm.[7] In addition, given that the chromatin molecule is fragmented, its fractal properties need to be considered. After calculating the search time for a target protein, alternating between the 3-D and 1-D diffusion phases on the chromatin fractal structure, it was deduced that facilitated diffusion in eukaryotes precipitates the searching process and minimizes the searching time by increasing the DNA-protein affinity.[7]

For oxygen

editThe oxygen affinity with hemoglobin on red blood cell surfaces enhances this bonding ability.[8] In a system of facilitated diffusion of oxygen, there is a tight relationship between the ligand which is oxygen and the carrier which is either hemoglobin or myoglobin.[9] This mechanism of facilitated diffusion of oxygen by hemoglobin or myoglobin was discovered and initiated by Wittenberg and Scholander.[10] They carried out experiments to test for the steady-state of diffusion of oxygen at various pressures. Oxygen-facilitated diffusion occurs in a homogeneous environment where oxygen pressure can be relatively controlled.[11] [12] For oxygen diffusion to occur, there must be a full saturation pressure (more) on one side of the membrane and full reduced pressure (less) on the other side of the membrane i.e. one side of the membrane must be of higher concentration. During facilitated diffusion, hemoglobin increases the rate of constant diffusion of oxygen and facilitated diffusion occurs when oxyhemoglobin molecule is randomly displaced.

For carbon monoxide

editFacilitated diffusion of carbon monoxide is similar to that of oxygen. Carbon monoxide also combines with hemoglobin and myoglobin,[12] but carbon monoxide has a dissociation velocity that 100 times less than that of oxygen. Its affinity for myoglobin is 40 times higher and 250 times higher for hemoglobin, compared to oxygen.[13]

For glucose

editSince glucose is a large molecule, its diffusion across a membrane is difficult.[14] Hence, it diffuses across membranes through facilitated diffusion, down the concentration gradient. The carrier protein at the membrane binds to the glucose and alters its shape such that it can easily to be transported.[15] Movement of glucose into the cell could be rapid or slow depending on the number of membrane-spanning protein. It is transported against the concentration gradient by a dependent glucose symporter which provides a driving force to other glucose molecules in the cells. Facilitated diffusion helps in the release of accumulated glucose into the extracellular space adjacent to the blood capillary.[15]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Pratt CA, Voet D, Voet JG (2002). Fundamentals of biochemistry upgrade. New York: Wiley. pp. 264–266. ISBN 0-471-41759-9.

- ^ Friedman, Morton (2008). Principles and models of biological transport. Springer. ISBN 978-0387-79239-2.

- ^ a b c Klenin, Konstantin V.; Merlitz, Holger; Langowski, Jörg; Wu, Chen-Xu (2006). "Facilitated Diffusion of DNA-Binding Proteins". Physical Review Letters. 96 (1): 018104. arXiv:physics/0507056. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..96a8104K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.018104. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 16486524. S2CID 8937433.

- ^ a b Bauer M, Metzler R (2013). "In vivo facilitated diffusion model". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e53956. arXiv:1301.5502. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...853956B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053956. PMC 3548819. PMID 23349772.

- ^ a b Hammar, P.; Leroy, P.; Mahmutovic, A.; Marklund, E. G.; Berg, O. G.; Elf, J. (2012). "The lac Repressor Displays Facilitated Diffusion in Living Cells". Science. 336 (6088): 1595–1598. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1595H. doi:10.1126/science.1221648. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22723426. S2CID 21351861.

- ^ Brackley CA, Cates ME, Marenduzzo D (September 2013). "Intracellular facilitated diffusion: searchers, crowders, and blockers". Phys. Rev. Lett. 111 (10): 108101. arXiv:1309.1010. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.111j8101B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.108101. PMID 25166711. S2CID 13220767.

- ^ a b Bénichou O, Chevalier C, Meyer B, Voituriez R (January 2011). "Facilitated diffusion of proteins on chromatin". Phys. Rev. Lett. 106 (3): 038102. arXiv:1006.4758. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106c8102B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.038102. PMID 21405302. S2CID 15977456.

- ^ Kreuzer, F. (1970). "Facilitated diffusion of oxygen and its possible significance; a review". Respiration Physiology. 9 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1016/0034-5687(70)90002-2. ISSN 0034-5687. PMID 4910215.

- ^ Jacquez JA, Kutchai H, Daniels E (June 1972). "Hemoglobin-facilitated diffusion of oxygen: interfacial and thickness effects" (PDF). Respir Physiol. 15 (2): 166–81. doi:10.1016/0034-5687(72)90096-5. hdl:2027.42/34087. PMID 5042165.

- ^ Rubinow SI, Dembo M (April 1977). "The facilitated diffusion of oxygen by hemoglobin and myoglobin". Biophys. J. 18 (1): 29–42. Bibcode:1977BpJ....18...29R. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(77)85594-X. PMC 1473276. PMID 856316.

- ^ Kreuzer F, Hoofd LJ (May 1972). "Factors influencing facilitated diffusion of oxygen in the presence of hemoglobin and myoglobin". Respir Physiol. 15 (1): 104–24. doi:10.1016/0034-5687(72)90008-4. PMID 5079218.

- ^ a b Wittenberg JB (January 1966). "The molecular mechanism of hemoglobin-facilitated oxygen diffusion". J. Biol. Chem. 241 (1): 104–14. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)96964-4. PMID 5901041.

- ^ Murray JD, Wyman J (October 1971). "Facilitated diffusion. The case of carbon monoxide". J. Biol. Chem. 246 (19): 5903–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)61811-3. PMID 5116656.

- ^ Thorens B (1993). "Facilitated glucose transporters in eithelial cells". Annu. Rev. Physiol. 55: 591–608. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.003111. PMID 8466187.

- ^ a b Carruthers, A. (1990). "Facilitated diffusion of glucose". Physiological Reviews. 70 (4): 1135–1176. doi:10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.1135. ISSN 0031-9333. PMID 2217557.