The smalltail shark (Carcharhinus porosus) is a species of requiem shark, and part of the family Carcharhinidae. It is found in the western Atlantic Ocean, from the northern Gulf of Mexico to southern Brazil. It inhabits shallow waters close to shore, particularly over muddy bottoms around estuaries. It tends to swim low in the water column and forms large aggregations segregated by sex. A slim species generally not exceeding 1.1 m (3.6 ft) in length, the smalltail shark has a rather long, pointed snout, a broad, triangular first dorsal fin, and a second dorsal fin that originates over the midpoint of the anal fin base. It is plain gray in color, without prominent markings on its fins.

| Smalltail shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Carcharhinus |

| Species: | C. porosus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharhinus porosus (Ranzani, 1839)

| |

| |

| Range of the smalltail shark[1][2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Carcharias henlei Müller & Henle, 1839

| |

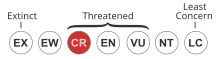

The diet of the smalltail shark consists mainly of bony fishes such as croakers, while crustaceans, cephalopods, and smaller sharks and rays may also be consumed. It is viviparous, meaning the developing embryos are sustained by a placental connection. Females bear litters of two to 9 young on a biennial cycle, following a roughly 12-month gestation period. The smalltail shark is often caught as bycatch and may be used for meat, fins, liver oil, cartilage, and fishmeal. It seems to have declined significantly since the 1980s. Therefore, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has listed it as critically endangered.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

editItalian naturalist Camillo Ranzani published the first scientific description of the smalltail shark in an 1839 volume of Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Instituti Bononiensis. He named the new shark Carcharias porosus from the Greek porus ("pore"), referring to the prominent pores behind its eyes.[3] The type specimen, a 1.2 m (3.9 ft)-long male from Brazil, has since been lost. This species was moved to the genus Carcharhinus by later authors.[4] Its Trinidadian name is puppy shark.[5]

The evolutionary relationships of the smalltail shark are uncertain. Based on morphology, Jack Garrick in 1982 and Leonard Compagno in 1988 tentatively placed it in a group defined by the whitecheek shark (C. dussumieri) and the blackspot shark (C. sealei).[6][7] This grouping was equivocally supported by Gavin Naylor's 1992 allozyme-based phylogenetic analysis.[8] Alternately, a 2011 phylogenetic study by Ximena Vélez-Zuazoa and Ingi Agnarsson, based on nuclear and mitochondrial genes, found close relationships between the smalltail shark, the daggernose shark (Isogomphodon oxyrhynchus), the blacknose shark (C. acronotus), and the finetooth shark (C. isodon).[9] The Pacific smalltail shark (C. cerdale) was once mistakenly synonymized with C. porosus, until 2011 when José Castro resurrected it as a distinct taxon.[2] An undescribed species closely similar to C. porosus is known from Southeast Asia.[4]

Description

editThe smalltail shark is a slender-bodied species with a fairly long, pointed snout. The leading margin of each nostril is enlarged into a narrow, pointed lobe. The large, circular eyes are equipped with nictitating membranes, and behind them is a series of prominent pores. The mouth bears short furrows at the corners and contains 13–15 tooth rows on either side of both jaws (usually 14 upper and 13 lower). The upper teeth are tall and triangular with strong serrations, becoming increasing oblique towards the sides. The lower teeth are comparatively narrower and more upright, with finer serrations.[4][5] The five pairs of gill slits are short.[10]

The small pectoral fins are falcate (sickle-shaped) with relatively pointed tips. The first dorsal fin is broad, forming nearly an equilateral triangle in adults, with a blunt apex; it originates over the pectoral fin rear tips. The second dorsal fin is small and originates over the midpoint of the anal fin base. No ridge exists between the dorsal fins. The pelvic fins are small with pointed to narrowly rounded tips, and the anal fin has a deep notch in its trailing margin. The asymmetrical caudal fin has a strong lower lobe and a longer upper lobe with a ventral notch near the tip.[4][5] The dermal denticles mostly do not overlap; each has three to five horizontal ridges leading to posterior teeth, with the central one the longest. This shark is plain gray to slate above and whitish below, with a faint lighter stripe on the flanks. The pectoral, dorsal, and caudal fins may darken toward the tips.[11] The smalltail shark reaches a maximum known length of 1.5 m (4.9 ft),[12] though 0.9–1.1 m (3.0–3.6 ft) is typical. Females grow larger than males.[11]

Distribution and habitat

editThe known range of the smalltail shark extends from the northern Gulf of Mexico to southern Brazil, excluding the Caribbean islands (aside from Trinidad and Tobago).[10] Its center of abundance is along the northern Brazilian coast, off Pará and Maranhão, where it is the most common shark.[1][13] This species has not been reported east of the Mississippi River in the past 50 years, despite historical evidence of a nursery area off Louisiana.[5] The smalltail shark can usually be found close to the bottom in inshore waters no deeper than 36 m (118 ft). Off northern Brazil, its environment is characterized by tides up to 7 m (23 ft) high and reaching 7.5 knots; the salinity fluctuates between 14 ppt in the rainy season and 34 ppt in the dry season, and the temperature ranges from 25 to 32 °C (77 to 90 °F). It favors estuarine areas with muddy bottoms.[1]

Biology and ecology

editThe smalltail shark forms large aggregations segregated by sex, with the males generally found deeper than the females.[5] It feeds mainly on bony fishes, including sea catfish, croakers, jacks, and grunts. Shrimp, crabs, and squid are secondary food sources, while adults are also capable of taking young sharpnose sharks (Rhizoprionodon), hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna), and stingrays (Dasyatis). Opportunistic in habits, the dietary composition of this shark generally reflects what is most available in its environment; off northern Brazil, the most important prey species are the croakers Macrodon ancylodon and Stellifer naso. Juveniles consume a wider variety of prey than adults.[14] In turn, the smalltail shark may potentially be preyed upon by larger sharks.[11]

Like other members of its family, the smalltail shark is viviparous: once the developing embryos exhaust their supply of yolk, the yolk sac develops into a placental connection through which the mother delivers nourishment. Females produce litters of two to 9 (typically four to six) young every other year; litter size increases with the size of the female. The gestation period lasts around 12 months. Reproduction occurs throughout the year, with a peak in birthing from September to November. Known nursery areas occur in shallow, murky waters off northern Brazil and Trinidad, where many bays and estuaries provide shelter and food.[5][13] The newborns measure 30–33 cm (12–13 in) long and grow an average of 7 cm (2.8 in) per year in their first four years of life. Males and females mature sexually at 70–93 cm (28–37 in) and 71–85 cm (28–33 in) long, respectively, corresponding to six years of age for both sexes. The average growth rate slows to 4 cm (1.6 in) per year after maturation. The maximum lifespan is at least 12 years.[5][15]

Human interactions

editHarmless to humans,[11] the smalltail shark is caught incidentally by gillnet and longline fisheries throughout its range. The meat is sold fresh, frozen, or dried and salted. In addition, the dried fins are exported for use in shark fin soup, the liver oil and cartilage are used medicinally, and the carcass is processed into fishmeal.[1][4] In 2006, the IUCN assessed this species, including Pacific populations now separated as C. cerdale, as data deficient due to a lack of fishery data.[1] In Trinidad, its abundance makes it the most economically important shark.[5] Off northern Brazil, substantial numbers are caught by gillnet fisheries targeting the Serra Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus brasiliensis). In the 1980s, this species constituted roughly 43% of the shark and ray catch, but has since declined to around 17%. This apparent decline is thought to have resulted from increasing fishing effort, the large proportion of juveniles captured, and the shark's low reproductive rate. Consequently, the IUCN has assessed the smalltail shark in Brazil as vulnerable, and noted the urgent need for conservation measures given that northern Brazil represents the center of the species' range. Although the smalltail shark was ostensibly given protection by inclusion on the 2004 Official List of Endangered Animals in Brazil, fishing remains effectively unmanaged.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Pollom, R.; Charvet, P.; Carlson, J.; Derrick, D.; Faria, V.; Lasso-Alcalá, O.M.; Marcante, F.; Mejía-Falla, P.A.; Navia, A.F.; Nunes, J.; Pérez Jiménez, J.C.; Rincon, G.; Dulvy, N.K. (2020). "Carcharhinus porosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T144136822A3094594. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T144136822A3094594.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b Castro, J.I. (January 15, 2011). "Resurrection of the name Carcharhinus cerdale, a species different from Carcharhinus porosus". Aqua. 17 (1): 1–10.

- ^ Ranzani, C. (1839). "De novis speciebus piscium". Novi Commentarii, Academiae Scientiarum Instituti Bononiensis. 4: 65–83.

- ^ a b c d e Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 496–497. ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Castro, J.H. (2011). The Sharks of North America. Oxford University Press. pp. 459–462. ISBN 978-0-19-539294-4.

- ^ Garrick, J.A.F. (1982). Sharks of the genus Carcharhinus. NOAA Technical Report, NMFS CIRC 445.

- ^ Compagno, L.J.V. (1988). Sharks of the Order Carcharhiniformes. Princeton University Press. pp. 319–320. ISBN 0-691-08453-X.

- ^ Naylor, G.J.P. (1992). "The phylogenetic relationships among requiem and hammerhead sharks: inferring phylogeny when thousands of equally most parsimonious trees result" (PDF). Cladistics. 8 (4): 295–318. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1992.tb00073.x. hdl:2027.42/73088. PMID 34929961. S2CID 39697113.

- ^ Vélez-Zuazoa, X.; Agnarsson, I. (February 2011). "Shark tales: A molecular species-level phylogeny of sharks (Selachimorpha, Chondrichthyes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 58 (2): 207–217. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.018. PMID 21129490.

- ^ a b McEachran, J.D.; Fechhelm, J.D. (1998). Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico: Myxinformes to Gasterosteiformes. University of Texas Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-292-75206-7.

- ^ a b c d Bester, C. Biological Profiles: Smalltail Shark. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on November 5, 2011.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Carcharhinus porosus". FishBase. November 2011 version.

- ^ a b Lessa R.; Santana, F.; Menni, R.; Almeida Z. (1999). "Population structure and reproductive biology of the smalltail shark (Carcharhinus porosus) off Maranhão, Brazil" (PDF). Marine and Freshwater Research. 50 (5): 383–388. doi:10.1071/mf98127.

- ^ Lessa, R.; Almeida, Z. (1997). "Analysis of stomach contents of the smalltail shark Carcharhinus porosus from northern Brazil". Cybium. 21 (2): 123–133.

- ^ Lessa, R.; Santana, F.M. (1998). "Age determination and growth of the smalltail shark Carcharhinus porosus, from northern Brazil". Marine and Freshwater Research. 49 (7): 705–711. doi:10.1071/mf98019.