There are 38 subspecies of Canis lupus listed in the taxonomic authority Mammal Species of the World (2005, 3rd edition). These subspecies were named over the past 250 years, and since their naming, a number of them have gone extinct. The nominate subspecies is the Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus lupus).

Taxonomy

editIn 1758, the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus published in his Systema Naturae the binomial nomenclature – or the two-word naming – of species. Canis is the Latin word meaning "dog",[3] and under this genus he listed the dog-like carnivores including domestic dogs, wolves, and jackals. He classified the domestic dog as Canis familiaris, and on the next page he classified the wolf as Canis lupus.[4] Linnaeus considered the dog to be a separate species from the wolf because of its head, body, and cauda recurvata – its upturning tail – which is not found in any other canid.[5]

In 1999, a study of mitochondrial DNA indicated that the domestic dog may have originated from multiple wolf populations, with the dingo and New Guinea singing dog "breeds" having developed at a time when human populations were more isolated from each other.[6] In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed under the wolf Canis lupus some 36 wild subspecies, and proposed two additional subspecies: familiaris Linnaeus, 1758 and dingo Meyer, 1793. Wozencraft included hallstromi – the New Guinea singing dog – as a taxonomic synonym for the dingo. Wozencraft referred to the mDNA study as one of the guides in forming his decision, and listed the 38 subspecies under the biological common name of "wolf", with the nominate subspecies being the Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus lupus) based on the type specimen that Linnaeus studied in Sweden.[7] However, the classification of several of these canines as either species or subspecies has recently[when?] been challenged.

List of extant subspecies

editLiving subspecies recognized by MSW3 as of 2005[update][7] and divided into Old World and New World:[8]

Eurasia and Australasia

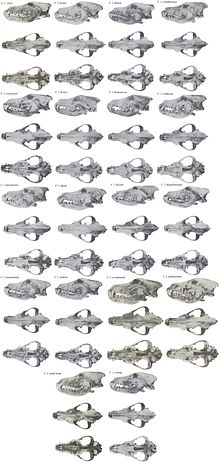

editSokolov and Rossolimo (1985) recognised nine Old World subspecies of wolf. These were C. l. lupus, C. l. albus, C. l. pallipes, C. l. cubanensis, C. l. campestris, C. l. chanco, C. l. desortorum, C. l. hattai, and C. l. hodophilax.[1] In his 1995 statistical analysis of skull morphometrics, mammalogist Robert Nowak recognized the first four of those subspecies, synonymized campestris, chanco and desortorum with C. l. lupus, but did not examine the two Japanese subspecies. In addition, he recognized C. l. communis as a subspecies distinct from C. l. lupus.[1] In 2003, Nowak also recognized the distinctiveness of C. l. arabs, C. l. hattai, C. l. italicus, and C. l. hodophilax.[9] In 2005, MSW3 included C. l. filchneri.[7] In 2003, two forms were distinguished in southern China and Inner Mongolia as being separate from C. l. chanco and C. l. filchneri and have yet to be named.[10][11]

| Subspecies | Image | Authority | Description | Range | Taxonomic synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. l. albus Tundra wolf |

Kerr, 1792[12] | A large, light-furred subspecies.[13] | Northern tundra and forest zones in the European and Asian parts of Russia and Kamchatka. Outside Russia, its range includes the extreme north of Scandinavia.[13] | dybowskii Domaniewski, 1926, kamtschaticus Dybowski, 1922, turuchanensis Ognev, 1923[14] | |

| C. l. arabs Arabian wolf |

Pocock, 1934[15] | A small, "desert-adapted" subspecies that is around 66 cm tall and weighs, on average, about 18 kg.[16] Its fur coat varies from short in the summer to long in the winter, possibly because of solar radiation.[17] | Southern Palestine, southern Israel, southern and western Iraq, Oman, Yemen, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and probably some parts of the Sinai Peninsula | ||

| C. l. campestris Steppe wolf |

Dwigubski, 1804 | An average-sized subspecies with short, coarse and sparse fur.[18] | Northern Ukraine, southern Kazakhstan, the Caucasus and the Trans-Caucasus[18] | bactrianus Laptev, 1929, cubanenesis Ognev, 1923, desertorum Bogdanov, 1882[19] | |

| C. l. chanco Himalayan wolf |

Matschie, 1907[20] | Long sharp face, elevated brows, broad head, large pointed ears, thick woolly pelage and very full brush of medial length. Above, dull earthy-brown; below, with the entire face and limbs yellowish-white.[21] | The Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau predominating above 4,000 metres in elevation[22] | laniger Hodgson, 1847 | |

| C. l. chanco Mongolian wolf |

Gray, 1863[23] | The fur is fulvous, on the back longer, rigid, with intermixed black and gray hairs; the throat, chest, belly, and inside of the legs pure white; head pale gray-brown; forehead grizzled with short black and gray hairs.[23] | Mongolia,[24] northern and central China,[10][11] Korea,[25] and the Ussuri River region of Russia[26] | coreanus Abe, 1923, dorogostaiskii Skalon, 1936, karanorensis Matschie, 1907, niger Sclater, 1874, tschiliensis Matschie, 1907 | |

| C. l. dingo Dingo and New Guinea singing dog |

Meyer, 1793 | Generally 52–60 cm tall at the shoulders and measures 117 to 124 cm from nose to tail tip. The average weight is 13 to 20 kg.[27] Fur color is mostly sandy- to reddish-brown, but can include tan patterns and can also be occasionally light brown, black or white.[28] | Australia and New Guinea | antarticus Kerr, 1792 [suppressed ICZN O451:1957], australasiae Desmarest, 1820, australiae Gray, 1826, dingoides Matschie, 1915, macdonnellensis Matschie, 1915, novaehollandiae Voigt, 1831, papuensis Ramsay, 1879, tenggerana Kohlbrugge, 1896, hallstromi Troughton, 1957, harappensis Prashad, 1936[29]

Sometimes included within Canis familiaris when the domestic dog is recognised as a species.[30] | |

| C. l. familiaris Domestic dog but refer Synonyms |

Linnaeus, 1758 | The domestic dog is a divergent subspecies of the gray wolf and was derived from an extinct population of Late Pleistocene wolves.[8][31][32] Through selective pressure and selective breeding, the domestic dog has developed into hundreds of varied breeds and shows more behavioral and morphological variation than any other land mammal.[33] | Worldwide in association with humans | Increasingly proposed as the species Canis familiaris but debated[34][30]

aegyptius Linnaeus, 1758,

alco C. E. H. Smith, 1839, americanus Gmelin, 1792, anglicus Gmelin, 1792, antarcticus Gmelin, 1792, aprinus Gmelin, 1792, aquaticus Linnaeus, 1758, aquatilis Gmelin, 1792, avicularis Gmelin, 1792, borealis C. E. H. Smith, 1839, brevipilis Gmelin, 1792, cursorius Gmelin, 1792, domesticus Linnaeus, 1758, extrarius Gmelin, 1792, ferus C. E. H. Smith, 1839, fricator Gmelin, 1792, fricatrix Linnaeus, 1758, fuillus Gmelin, 1792, gallicus Gmelin, 1792, glaucus C. E. H. Smith, 1839, graius Linnaeus, 1758, grajus Gmelin, 1792, hagenbecki Krumbiegel, 1950, haitensis C. E. H. Smith, 1839, hibernicus Gmelin, 1792, hirsutus Gmelin, 1792, hybridus Gmelin, 1792, islandicus Gmelin, 1792, italicus Gmelin, 1792, laniarius Gmelin, 1792, leoninus Gmelin, 1792, leporarius C. E. H. Smith, 1839, major Gmelin, 1792, mastinus Linnaeus, 1758, melitacus Gmelin, 1792, melitaeus Linnaeus, 1758, minor Gmelin, 1792, molossus Gmelin, 1792, mustelinus Linnaeus, 1758, obesus Gmelin, 1792, orientalis Gmelin, 1792, pacificus C. E. H. Smith, 1839, plancus Gmelin, 1792, pomeranus Gmelin, 1792, sagaces C. E. H. Smith, 1839, sanguinarius C. E. H. Smith, 1839, sagax Linnaeus, 1758, scoticus Gmelin, 1792, sibiricus Gmelin, 1792, suillus C. E. H. Smith, 1839, terraenovae C. E. H. Smith, 1839, terrarius C. E. H. Smith, 1839, turcicus Gmelin, 1792, urcani C. E. H. Smith, 1839, variegatus Gmelin, 1792, venaticus Gmelin, 1792, vertegus Gmelin, 1792[35] | |

| C. l. italicus Italian wolf |

Altobello, 1921 | The pelt is generally of a grey-fulvous colour, which reddens in summer. The belly and cheeks are more lightly coloured, and dark bands are present on the back and tail tip, and occasionally along the fore limbs. | Native to the Italian Peninsula; recently expanded into Switzerland and southeastern France. | lupus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| C. l. lupus Eurasian wolf (nominate subspecies) |

Linnaeus, 1758[36] | Generally a large subspecies with rusty ocherous or light gray fur.[37] | Has the largest range among wolf subspecies and is the most common subspecies in Europe and Asia, ranging through Western Europe, Scandinavia, the Caucasus, Russia, China, and Mongolia. Its habitat overlaps with the Indian wolf in some regions of Turkey. | altaicus Noack, 1911, argunensis Dybowski, 1922, canus Sélys Longchamps, 1839, communis Dwigubski, 1804, deitanus Cabrera, 1907, desertorum Bogdanov, 1882, flavus Kerr, 1792, fulvus Sélys Longchamps, 1839, kurjak Bolkay, 1925, lycaon Trouessart, 1910, major Ogérien, 1863, minor Ogerien, 1863, niger Hermann, 1804, orientalis Wagner, 1841, orientalis Dybowski, 1922[38] | |

| C. l. pallipes Indian wolf |

Sykes, 1831 | A small subspecies with pelage shorter than that of northern wolves and with little to no underfur.[39] Fur color ranges from grayish-red to reddish-white with black tips. The dark V-shaped stripe over the shoulders is much more pronounced than in northern wolves. The underparts and legs are more or less white.[40] | India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, northern Israel, and northern Palestine[41] | ||

| C. l. signatus Iberian wolf |

Cabrera, 1907 | A subspecies with slighter frame than C. l. lupus, white marks on the upper lips, dark marks on the tail, and a pair of dark marks on its front legs. | Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, which includes northwestern Spain and northern Portugal | lupus Linnaeus, 1758 |

North America

editFor North America, in 1944 the zoologist Edward Goldman recognized as many as 23 subspecies based on morphology.[42] In 1959, E. Raymond Hall proposed that there had been 24 subspecies of lupus in North America.[43] In 1970, L. David Mech proposed that there was "probably far too many subspecific designations...in use", as most did not exhibit enough points of differentiation to be classified as separate subspecies.[44] The 24 subspecies were accepted by many authorities in 1981 and these were based on morphological or geographical differences, or a unique history.[45] In 1995, the American mammalogist Robert M. Nowak analyzed data on the skull morphology of wolf specimens from around the world. For North America, he proposed that there were only five subspecies of the wolf. These include a large-toothed Arctic wolf named C. l. arctos, a large wolf from Alaska and western Canada named C. l. occidentalis, a small wolf from southeastern Canada named C. l. lycaon, a small wolf from the southwestern U.S. named C. l. baileyi and a moderate-sized wolf that was originally found from Texas to Hudson Bay and from Oregon to Newfoundland named C. l. nubilus.[46][1]

The taxonomic classification of Canis lupus in Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition, 2005) listed 27 subspecies of North American wolf,[7] corresponding to the 24 Canis lupus subspecies and the three Canis rufus subspecies of Hall (1981).[1] The table below shows the extant subspecies, with the extinct ones listed in the following section.

| Subspecies | Image | Authority | Description | Range | Taxonomic synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. l. arctos Arctic wolf |

Pocock, 1935[47] | A medium-sized, almost completely white subspecies.[48] | Melville Island (the Northwest Territories and Nunavut), Ellesmere Island | The current (2022) classification of the more broadly defined C. l. arctos of Nowak (1995) synonymizes C. l. orion and C. l. bernardi.[1][49] | |

| C. l. baileyi Mexican wolf |

Nelson and Goldman, 1929[50] | The smallest of the North American subspecies, with dark fur.[51] | found in southwestern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona as well as northern Mexico; once ranged into western Texas | ||

| C. l. columbianus British Columbian wolf |

Goldman, 1941 | Smaller-sized; unique diet of fish and smaller-sized deer in temperate rainforest; similar to crassodon. | Coastal British Columbia and coastal Yukon | Currently (2023) synonymized under C. l. crassodon. | |

| C. l. crassodon Vancouver Island wolf |

Hall, 1932 | A medium-sized subspecies with grayish fur; similar to columbianus.[52] | Vancouver Island, British Columbia | Currently (2023) C. l. crassodon synonymizes C. l. ligoni and C. l. columbianus. | |

| C. l. familiaris Domestic dog but refer Synonyms |

worldwide | The domestic dog is a divergent subspecies of the gray wolf and was derived from an extinct population of Late Pleistocene wolves.[8][31][32] Through selective pressure and selective breeding, the domestic dog has developed into hundreds of varied breeds and shows more behavioral and morphological variation than any other land mammal.[33]

aegyptius Linnaeus, 1758,

alco C. E. H. Smith, 1839, americanus Gmelin, 1792, anglicus Gmelin, 1792, antarcticus Gmelin, 1792, aprinus Gmelin, 1792, aquaticus Linnaeus, 1758, aquatilis Gmelin, 1792, avicularis Gmelin, 1792, borealis C. E. H. Smith, 1839, brevipilis Gmelin, 1792, cursorius Gmelin, 1792, domesticus Linnaeus, 1758, extrarius Gmelin, 1792, ferus C. E. H. Smith, 1839, fricator Gmelin, 1792, fricatrix Linnaeus, 1758, fuillus Gmelin, 1792, gallicus Gmelin, 1792, glaucus C. E. H. Smith, 1839, graius Linnaeus, 1758, grajus Gmelin, 1792, hagenbecki Krumbiegel, 1950, haitensis C. E. H. Smith, 1839, hibernicus Gmelin, 1792, hirsutus Gmelin, 1792, hybridus Gmelin, 1792, islandicus Gmelin, 1792, italicus Gmelin, 1792, laniarius Gmelin, 1792, leoninus Gmelin, 1792, leporarius C. E. H. Smith, 1839, major Gmelin, 1792, mastinus Linnaeus, 1758, melitacus Gmelin, 1792, melitaeus Linnaeus, 1758, minor Gmelin, 1792, molossus Gmelin, 1792, mustelinus Linnaeus, 1758, obesus Gmelin, 1792, orientalis Gmelin, 1792, pacificus C. E. H. Smith, 1839, plancus Gmelin, 1792, pomeranus Gmelin, 1792, sagaces C. E. H. Smith, 1839, sanguinarius C. E. H. Smith, 1839, sagax Linnaeus, 1758, scoticus Gmelin, 1792, sibiricus Gmelin, 1792, suillus C. E. H. Smith, 1839, terraenovae C. E. H. Smith, 1839, terrarius C. E. H. Smith, 1839, turcicus Gmelin, 1792, urcani C. E. H. Smith, 1839, variegatus Gmelin, 1792, venaticus Gmelin, 1792, vertegus Gmelin, 1792[53]Increasingly proposed as the species Canis familiaris but debated[54][30] | |||

| C. l. hudsonicus Hudson Bay wolf |

Goldman, 1941 | A light-colored subspecies similar to occidentalis, but smaller.[55] | Northern Manitoba and the Northwest Territories | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. nubilus[1][56] | |

| C. l. irremotus Northern Rocky Mountain wolf |

Goldman, 1937[57][58] | A medium-sized to large subspecies with pale fur.[59] | The northern Rocky Mountains | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. occidentalis[1][60] | |

| C. l. labradorius Labrador wolf |

Goldman, 1937[57] | A medium-sized, light-colored subspecies.[61] | Labrador and northern Quebec; confirmed presence on Newfoundland[62][63] | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. nubilus[1][64] | |

| C. l. ligoni Alexander Archipelago wolf |

Goldman, 1937[57] | A medium-sized, dark-colored subspecies.[65] | The Alexander Archipelago, Alaska | Currently (2023) synonymized under C. l. crassodon. | |

| C. l. lycaon Eastern wolf but refer Synonyms |

Schreber, 1775 | Two forms are known – a small, reddish-brown colored form called the Algonquin wolf; and a slightly larger, more grayish-brown form called the Great Lakes wolf, which is an admixture of the Algonquin wolf and other gray wolves.[66] | The Algonquin form occupies central Ontario and southwestern Quebec, particularly in and nearby protected areas, such as Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, and possibly extreme northeastern U.S. and western New Brunswick. The Great Lakes form occupies northern Ontario, Wisconsin and Minnesota, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and southern Manitoba. Overlaps of the two forms occur, with intermixing in the southern portions of northern Ontario. | canadensis de Blainville, 1843, ungavensis Comeau, 1940[67] The Algonquin form is currently (2022) recognized as the species Canis lycaon[68] by the American Society of Mammalogists, but its taxonomy is still debated.[69] | |

| C. l. mackenzii Mackenzie River wolf |

Anderson, 1943 | A subspecies with variable fur and intermediate in size between occidentalis and manningi.[70] | The southern Northwest Territories | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. occidentalis[1][71] | |

| C. l. manningi Baffin Island wolf |

Anderson, 1943 | The smallest subspecies of the Arctic, with buffy-white fur.[72] | Baffin Island | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. nubilus[1][73] | |

| C. l. occidentalis Northwestern wolf |

Richardson, 1829 | A very large, usually light-colored subspecies, and the biggest subspecies.[74] | Alaska, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and the northwestern United States | ater Richardson, 1829, sticte Richardson, 1829[75]

The C. l. occidentalis of Nowak (1995) synonymizes alces, columbianus, griseoalbus, mackenzii, pambasileus and tundrarum, which is the currently (2022) recognized classification.[1] | |

| C. l. orion Greenland wolf |

Pocock, 1935 | Greenland and the Queen Elizabeth Islands[76] | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. arctos[1][77] | ||

| C. l. pambasileus Alaskan Interior wolf |

Miller, 1912 | The second largest subspecies of wolf, second in skull and tooth proportions only to occidentalis (see chart above), with fur that is black, white or a mixture of both in color.[78] | The Alaskan Interior and Yukon, save for the tundra region of the Arctic Coast[79] | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. occidentalis[1][80] | |

| C. l. nubilus Great Plains wolf |

Say, 1823 | A medium-sized, light-colored subspecies.[81] | Throughout the Great Plains from southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan southward to northern Texas[82] | variabilis Wied-Neuwied, 1841.[83] Previously thought extinct in 1926, the Great Plains wolf's descendants were found in the northeastern region of the United States and have become federally protected since 1974.[84]

As of 2022 the classification of the more broadly defined C. l. nubilus of Nowak (1995) synonymizes beothucus, fuscus, hudsonicus, irremotus, labridorius, manningi, mogollonensis, monstrabilis and youngi, in which case the subspecies is extant in Canada (see infobox map).[1] | |

| C. l. rufus Red wolf but refer Synonyms |

Audubon and Bachman, 1851 | Has a brownish or cinnamon pelt, with gray and black shading on the back and tail. Generally intermediate in size between other North American wolf subspecies and the coyote. Like other wolves, it has almond-shaped eyes, a broad muzzle and a wide nose pad though, like the coyote, its ears are proportionately larger. It has a deeper profile, a longer and broader head than the coyote, and has a less prominent ruff than other wolves.[85] | Historically distributed throughout the Eastern, Southern, and Midwestern United States, from southernmost New York south to Florida and west to Texas. Modern range is eastern North Carolina.[86] | Currently considered a distinct species, Canis rufus, but this proposal is still debated.[2] As a species, the red wolf would have the following subspecies:

| |

| C. l. tundrarum Alaskan tundra wolf |

Miller, 1912 | A large, white-colored subspecies closely resembling pambasileus, though lighter in color.[87] | The Barren Grounds of the Arctic Coast region from near Point Barrow eastward toward Hudson Bay and probably northwards to the Arctic Archipelago[88] | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. occidentalis[1][89] |

List of extinct subspecies

edit| Subspecies | Image | Authority | Description | Range | Taxonomic synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| † C. l. maximus | Boudadi-Maligne, 2012[90] | The largest subspecies of all known extinct and extant wolves from Western Europe. The wolf's long bones are 10% longer than those of extant European wolves, 12% larger than those of C. l. santenaisiensis and 20% longer than those of C. l. lunellensis.[90] The teeth are robust, the posterior denticules on the lower premolars p2, p3, p4 and upper P2 and P3 are highly developed, and the diameter of the lower carnassial (m1) were larger than any known European wolf.[90] | Jaurens Cave, southern France | ||

| † C. l. spelaeus Cave wolf |

Goldfuss, 1823[91] | Its bone proportions are close to those of the Canadian Arctic-boreal mountain-adapted timber wolf and a little larger than those of the modern European wolf.[92] | Across Europe | brevis Kuzmina, 1994[93] | |

| † Unnamed Late Pleistocene Italian subspecies | Berte, Pandolfi, 2014[94] | Known from fragmentary remains, it was a large subspecies comparable in size and shape to C. l. maximus.[94] | Avetrana (Italy) |

Subspecies recognized by MSW3 as of 2005[update] which have gone extinct over the past 150 years:[7]

| Subspecies | Image | Authority | Description | Range | Taxonomic synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| † C. l. alces Kenai Peninsula wolf |

Goldman, 1941[95] | One of the largest North American subspecies, similar to pambasileus. Its fur color is unknown.[96] | The Kenai Peninsula, Alaska | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. occidentalis[1][97] | |

| † C. l. beothucus Newfoundland wolf |

G. M. Allen and Barbour, 1937 | A medium-sized, white-furred subspecies.[98] Its former range is slowly being claimed by its relative, the Labrador wolf (C. l. labradorius). | Newfoundland | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. nubilus[1][99] | |

| † C. l. bernardi Banks Island wolf |

Anderson, 1943 | A large, slender subspecies with a narrow muzzle and large carnassials.[100] | Limited to Banks and Victoria Islands in the Canadian Arctic | banksianus Anderson, 1943[101] | |

| † C. l. floridanus Florida black wolf but refer Synonyms |

Miller, 1912 | A jet-black subspecies that is described as having been extremely similar to the red wolf in both size and weight.[103] This subspecies became extinct in 1908.[104] | Florida | Currently (2022) recognized as a subspecies of Canis rufus[2] as Canis rufus floridanus, but debated | |

| † C. l. fuscus Cascade Mountains wolf |

Richardson, 1839 | A cinnamon-colored subspecies similar to columbianus and irremotus, but darker in color.[105] | The Cascade Range | gigas Townsend, 1850[106] | |

| † C. l. gregoryi Mississippi Valley wolf but refer Synonyms |

Goldman, 1937[57] | A medium-sized subspecies, though slender and tawny; its coat contained a mixture of various colors, including black, white, gray and cinnamon.[57] | In and around the lower Mississippi River basin | Currently (2022) recognized as a subspecies of Canis rufus[2] as Canis rufus gregoryi, but debated | |

| † C. l. griseoalbus Manitoba wolf |

Baird, 1858 | Northern Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba | knightii Anderson, 1945[108]

Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. occidentalis[1][109] | ||

| † C. l. hattai Hokkaidō wolf |

Kishida, 1931 | Similar in size, and related to, the wolves of North America.[110] | Hokkaido, Sakhalin,[111][112] the Kamchatkan Peninsula, and Iturup and Kunashir Islands just to the east of Hokkaido in the Kuril Archipelago[112] | rex Pocock, 1935[113] | |

| † C. l. hodophilax Japanese wolf |

Temminck, 1839 | Smaller in size compared to other subspecies, except for the Arabian wolf (C. l. arabs).[112] | Japanese islands of Honshū, Shikoku, and Kyūshū (but not Hokkaido)[114][115] | japonicus Nehring, 1885[116] | |

| † C. l. mogollonensis Mogollon Mountains wolf |

Goldman, 1937[57] | A small, dark-colored subspecies, intermediate in size between youngi and baileyi.[117] | Arizona and New Mexico | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. nubilus[1][118] | |

| † C. l. monstrabilis Texas wolf |

Goldman, 1937[57] | Similar in size and color to mogollonensis and possibly the same subspecies.[119] | Texas, New Mexico, and northern Mexico | niger Bartram, 1791[120] | |

| † C. l. youngi Southern Rocky Mountain wolf |

Goldman, 1937[57] | A medium-sized, light-colored subspecies closely resembling nubilus, though larger, with more blackish-buff hairs on the back.[122] | Southeastern Idaho, southwestern Wyoming, northeastern Nevada, Utah, western and central Colorado, northwestern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico | Currently (2022) synonymized under C. l. nubilus[1][123] |

Subspecies discovered since the publishing of MSW3 in 2005 which have gone extinct over the past 150 years:

| Subspecies | Image | Authority | Description | Range | Taxonomic synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| † Canis lupus cristaldii Sicilian wolf |

Angelici and Rossi, 2018[124] | A slender, short-legged subspecies with light, tawny-colored fur. The dark bands present on the forelimbs of the mainland Italian wolf were absent or poorly defined in the Sicilian wolf. | Sicily |

Disputed subspecies

editGlobal

editIn 2019, a workshop hosted by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group considered the New Guinea singing dog and the dingo to be feral dogs (Canis familiaris).[125] In 2020, a literature review of canid domestication stated that modern dogs were not descended from the same Canis lineage as modern wolves, and proposed that dogs may be descended from a Pleistocene wolf closer in size to a village dog.[126] In 2021, the American Society of Mammalogists also considered dingos a feral dog (Canis familiaris) population.[30]

Eurasia

editItalian wolf

editThe Italian wolf (or Apennine wolf) was first recognised as a distinct subspecies (Canis lupus italicus) in 1921 by zoologist Giuseppe Altobello.[127] Altobello's classification was later rejected by several authors, including Reginald Innes Pocock, who synonymised C. l. italicus with C. l. lupus.[128] In 2002, the noted paleontologist R.M. Nowak reaffirmed the morphological distinctiveness of the Italian wolf and recommended the recognition of Canis lupus italicus.[128] A number of DNA studies have found the Italian wolf to be genetically distinct.[129][130] In 2004, the genetic distinction of the Italian wolf subspecies was supported by analysis which consistently assigned all the wolf genotypes of a sample in Italy to a single group. This population also showed a unique mitochondrial DNA control-region haplotype, the absence of private alleles and lower heterozygosity at microsatellite loci, as compared to other wolf populations.[131] In 2010, a genetic analysis indicated that a single wolf haplotype (w22) unique to the Apennine Peninsula and one of the two haplotypes (w24, w25), unique to the Iberian Peninsula, belonged to the same haplogroup as the prehistoric wolves of Europe. Another haplotype (w10) was found to be common to the Iberian peninsula and the Balkans. These three populations with geographic isolation exhibited a near lack of gene flow and spatially correspond to three glacial refugia.[132]

The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition, 2005) does not recognize Canis lupus italicus; however, NCBI/Genbank publishes research papers under that name.[133]

Iberian wolf

editThe Iberian wolf was first recognised as a distinct subspecies (Canis lupus signatus) in 1907 by zoologist Ángel Cabrera. The wolves of the Iberian peninsula have morphologically distinct features from other Eurasian wolves and each are considered by their researchers to represent their own subspecies.[134][135]

The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition, 2005) does not recognize Canis lupus signatus; however, NCBI/Genbank does list it.[136]

Himalayan wolf

edit| Phylogenetic tree with timing in years for Canis lupus[a] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Himalayan wolf is distinguished by its mitochondrial DNA, which is basal to all other wolves. The taxonomic name of this wolf is disputed, with the species Canis himalayensis being proposed based on two limited DNA studies.[137][138][139] In 2017, a study of mitochondrial DNA, X-chromosome (maternal lineage) markers and Y-chromosome (male lineage) markers found that the Himalayan wolf was genetically basal to the Holarctic grey wolf and has an association with the African golden wolf.[140]

In 2019, a workshop hosted by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group noted that the Himalayan wolf's distribution included the Himalayan range and the Tibetan Plateau. The group recommends that this wolf lineage be known as the "Himalayan wolf" and classified as Canis lupus chanco until a genetic analysis of the holotypes is available.[125] In 2020, further research on the Himalayan wolf found that it warranted species-level recognition under the Unified Species Concept, the Differential Fitness Species Concept, and the Biological Species Concept. It was identified as an Evolutionary Significant Unit that warranted assignment onto the IUCN Red List for its protection.[141]

Indian plains wolf

editThe Indian plains wolf is a proposed clade within the Indian wolf (Canis lupus pallipes) that is distinguished by its mitochondrial DNA, which is basal to all other wolves except for the Himalayan wolf. The taxonomic status of this wolf clade is disputed, with the separate species Canis indica being proposed based on two limited DNA studies.[137][138] The proposal has not been endorsed because it relied on a limited number of museum and zoo samples that may not have been representative of the wild population, and a call for further fieldwork has been made.[139]

The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition, 2005) does not recognize Canis indica; however, NCBI/Genbank lists it as a new subspecies, Canis lupus indica.[142]

Southern Chinese wolf

editIn 2017, a comprehensive study found that the gray wolf was present across all of mainland China, both in the past and today. It exists in southern China, which refutes claims made by some researchers in the Western world that the wolf had never existed in southern China.[143][144] This wolf has not been taxonomically classified.[10][11]

In 2019, a genomic study on the wolves of China included museum specimens of wolves from southern China that were collected between 1963 and 1988. The wolves in the study formed three clades: northern Asian wolves that included those from northern China and eastern Russia, Himalayan wolves from the Tibetan Plateau, and a unique population from southern China. One specimen from Zhejiang Province in eastern China shared gene flow with the wolves from southern China; however, its genome was 12–14 percent admixed with a canid that may be the dhole or an unknown canid that predates the genetic divergence of the dhole. The wolf population from southern China is believed to still exist in that region.[145]

North America

editCoastal wolves

editA study of the three coastal wolves indicates a close phylogenetic relationship across regions that are geographically and ecologically contiguous, and the study proposed that Canis lupus ligoni (the Alexander Archipelago wolf), Canis lupus columbianus (the British Columbian wolf), and Canis lupus crassodon (the Vancouver Coastal Sea wolf) should be recognized as a single subspecies of Canis lupus, synonymized as Canis lupus crassodon.[146] They share the same habitat and prey species, and form one study's six identified North American ecotypes – a genetically and ecologically distinct population separated from other populations by their different types of habitat.[147][148]

Eastern wolf

editThe eastern wolf has two proposals over its origin. One is that the eastern wolf is a distinct species (C. lycaon) that evolved in North America, as opposed to the gray wolf that evolved in the Old World, and is related to the red wolf. The other is that it is derived from admixture between gray wolves, which inhabited the Great Lakes area and coyotes, forming a hybrid that was classified as a distinct species by mistake.[149]

The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition, 2005) does not recognize Canis lycaon; however, NCBI/Genbank does list it.[150] In 2021, the American Society of Mammalogists also considered Canis lycaon a valid species.[151]

Red wolf

editThe red wolf is an enigmatic taxon, of which there are two proposals over its origin. One is that the red wolf is a distinct species (C. rufus) that has undergone human-influenced admixture with coyotes. The other is that it was never a distinct species but was derived from past admixture between coyotes and gray wolves, due to the gray wolf population being eliminated by humans.[149]

The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition, 2005) does not recognize Canis rufus; however, NCBI/Genbank does list it.[152] In 2021, the American Society of Mammalogists also considered Canis rufus a valid species.[153]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ For a full set of supporting references, refer to note (a) in the phylotree at Evolution of the wolf

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Nowak, R. M. (1995). "Another look at wolf taxonomy" (PDF). In Carbyn, L. N.; Fritts, S. H.; D. R. Seip (eds.). Ecology and conservation of wolves in a changing world: proceedings of the second North American symposium on wolves. Edmonton, Canada: Canadian Circumpolar Institute, University of Alberta. pp. 375–397.

- ^ a b c d Chambers SM, Fain SR, Fazio B, Amaral M (2012). "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna. 77: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "canine". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Linnæus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiæ (Stockholm): Laurentius Salvius. pp. 39–40. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1995). "2-Origins of the dog". In Serpell, James (ed.). The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–20. ISBN 0521415292.

- ^ Wayne, R.; Ostrander, Elaine A. (1999). "Origin, genetic diversity, and genome structure of the domestic dog". BioEssays. 21 (3): 247–257. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199903)21:3<247::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10333734. S2CID 5547543.

- ^ a b c d e Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Canis lupus". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Fan, Zhenxin; Silva, Pedro; Gronau, Ilan; Wang, Shuoguo; Armero, Aitor Serres; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ramirez, Oscar; Pollinger, John; Galaverni, Marco; Ortega Del-Vecchyo, Diego; Du, Lianming; Zhang, Wenping; Zhang, Zhihe; Xing, Jinchuan; Vilà, Carles; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Godinho, Raquel; Yue, Bisong; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Worldwide patterns of genomic variation and admixture in gray wolves". Genome Research. 26 (#2): 163–73. doi:10.1101/gr.197517.115. PMC 4728369. PMID 26680994.

- ^ Mech & Boitani 2003, pp. 245–246

- ^ a b c Andrew T. Smith; Yan Xie; Robert S. Hoffmann; Darrin Lunde; John MacKinnon; Don E. Wilson; W. Chris Wozencraft, eds. (2008). A Guide to the Mammals of China. Princeton University press. pp. 416–418. ISBN 978-0691099842.

- ^ a b c Wang, Yingxiang (2003). A Complete Checklist of Mammal Species and Subspecies in China (A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference). China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, China. ISBN 978-7503831317.

- ^ "Canis lupus albus Kerr, 1792". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ a b Heptner, V. G. & Naumov, N., P. (1998) Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol. II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc., USA, pp. 182-184, ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "Canis lupus arabs Pocock, 1934". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ Lopez, Barry (1978). Of wolves and men. New York: Scribner Classics. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-7432-4936-2.

- ^ Fred H. Harrington; Paul C. Paquet (1982). Wolves of the World: Perspectives of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Elsevier Science. p. 474. ISBN 978-0-8155-0905-9.

- ^ a b Heptner, V. G. & Naumov, N., P. (1998) Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol. II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc., USA, pp. 188-89, ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Matschie, P. (1908). "Über Chinesische Säugetiere". In Filchner, W. (ed.). Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Expedition Filchner nach China und Tibet, 1903-1905. Berlin: Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn. pp. 134−242.

- ^ Hodgson, B. H. (1847). "Description of the wild ass (Asinus polydon) and wolf of Tibet (Lupus laniger)". Calcutta Journal of Natural History. 7: 469–477.

- ^ Werhahn, G.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Cheng, C.; Lu, Z.; Atzeni, L.; Deng, Z.; Kun, S.; Shao, X.; Lu, Q.; Joshi, J.; Man Sherchan, A.; Karmacharya, D.; Kumari Chaudhary, H.; Kusi, N.; Weckworth, B.; Kachel, S.; Rosen, T.; Kubanychbekov, Z.; Karimov, K.; Kaden, J.; Ghazali, M.; MacDonald, D. W.; Sillero-Zubiri, C.; Senn, H. (2020). "Himalayan wolf distribution and admixture based on multiple genetic markers". Journal of Biogeography. 47 (6): 1272–1285. Bibcode:2020JBiog..47.1272W. doi:10.1111/jbi.13824.

- ^ a b Gray, J. E. (1863). "Notice of the chanco or golden wolf (Canis chanco) from Chinese Tartary". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 94.

- ^ Mivart, S. G. (1890). "The Common Wolf". Dogs, Jackals, Wolves, and Foxes : A Monograph of the Canidæ. London: E. H. Porter and Dulau & Co. pp. 3–17.

- ^ Abe, Y. (1923). "Nukutei ni tisuit". Dobutsugaku Zasshi Zoological Magazine. 35: 320−386.

- ^ Heptner, V. G.; Naumov, N. P.; Yurgenson, P. B.; Sludskii, A. A.; Chirkova, A. F.; Bannikov, A. G. (1998) [1967]. "Wolf". Mlekopitaiushchie Sovetskogo Soiuza [Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a. Sirenia and Carnivora (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears)]. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science. pp. 164−270.

- ^ Ben Allen (2008). "Home Range, Activity Patterns, and Habitat use of Urban Dingoes" (PDF). 14th Australasian Vertebrate Pest Conference. Invasive Animals CRC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ^ Fleming, Peter; Laurie Corbett; Robert Harden; Peter Thomson (2001). Managing the Impacts of Dingoes and Other Wild Dogs. Commonwealth of Australia: Bureau of Rural Sciences.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d "Canis familiaris". ASM Mammal Diversity Database. 1.5. American Society of Mammalogists. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ a b Freedman, Adam H.; Gronau, Ilan; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, Diego; Han, Eunjung; Silva, Pedro M.; Galaverni, Marco; Fan, Zhenxin; Marx, Peter; Lorente-Galdos, Belen; Beale, Holly; Ramirez, Oscar; Hormozdiari, Farhad; Alkan, Can; Vilà, Carles; Squire, Kevin; Geffen, Eli; Kusak, Josip; Boyko, Adam R.; Parker, Heidi G.; Lee, Clarence; Tadigotla, Vasisht; Siepel, Adam; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Harkins, Timothy T.; Nelson, Stanley F.; Ostrander, Elaine A.; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Wayne, Robert K.; et al. (2014). "Genome Sequencing Highlights the Dynamic Early History of Dogs". PLOS Genetics. 10 (#1): e1004016. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016. PMC 3894170. PMID 24453982.

- ^ a b Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V. J.; Sawyer, S. K.; Greenfield, D. L.; Germonpre, M. B.; Sablin, M. V.; Lopez-Giraldez, F.; Domingo-Roura, X.; Napierala, H.; Uerpmann, H.-P.; Loponte, D. M.; Acosta, A. A.; Giemsch, L.; Schmitz, R. W.; Worthington, B.; Buikstra, J. E.; Druzhkova, A.; Graphodatsky, A. S.; Ovodov, N. D.; Wahlberg, N.; Freedman, A. H.; Schweizer, R. M.; Koepfli, K.- P.; Leonard, J. A.; Meyer, M.; Krause, J.; Paabo, S.; et al. (2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. 342 (#6160): 871–4. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..871T. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. hdl:10261/88173. PMID 24233726. S2CID 1526260.

- ^ a b Spady TC, Ostrander EA (January 2008). "Canine Behavioral Genetics: Pointing Out the Phenotypes and Herding up the Genes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (#1): 10–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.001. PMC 2253978. PMID 18179880.

- ^ Serpell, James (2016-12-08). The domestic dog : its evolution, behavior and interactions with people. Serpell, James, 1952-, Barrett, Priscilla (Second ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. p. 8. ISBN 9781107024144. OCLC 957339355.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "Canis lupus lupus Linnaeus, 1758". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ Heptner, V. G. & Naumov, N., P. (1998) Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol. II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc., USA, pp. 184-87, ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "NATURAL HISTORY OF THE MAMMALIA OF INDIA AND CEYLON by Robert A. Sterndale, THACKER, SPINK, AND CO. BOMBAY: THACKER AND CO., LIMITED. LONDON: W. THACKER AND CO. 1884".

- ^ A monograph of the canidae by St. George Mivart, F.R.S, published by Alere Flammam. 1890

- ^ REICHMANN, ALON; SALTZ, DAVID (2005-01-01). "The Golan Wolves: The Dynamics, Behavioral Ecology, and Management of an Endangered Pest". Israel Journal of Zoology. 51 (2): 87–133. doi:10.1560/1BLK-B1RT-XB11-BWJH (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 0021-2210.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America. Vol. 2. Dover Publications, New York. pp. 413–477. ISBN 978-0486211930.

- ^ The Mammals of North America, E. Raymond Hall & Keith R. Kelson, Ronald Press New York, 1959

- ^ Mech, L. David. 1970. The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

- ^ The Mammals of North America, E. Raymond Hall, Wiley New York, 1981

- ^ Nowak, R. (2003). "Wolf Evolution and Taxonomy". In Mech, L. David; Boitani, Luigi (eds.). Wolves: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. pp. 239−258. ISBN 978-0-226-51696-7.

- ^ "Canis lupus arctos Pocock, 1935". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 430-31

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ "Canis lupus baileyi Nelson and Goldman, 1929". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 469-71

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 459-60

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Serpell, James (2016-12-08). The domestic dog : its evolution, behavior and interactions with people. Serpell, James, 1952-, Barrett, Priscilla (Second ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. p. 8. ISBN 9781107024144. OCLC 957339355.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 427-29

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goldman, E. A. (1937). "The Wolves of North America". Journal of Mammalogy. 18 (1): 37–45. doi:10.2307/1374306. ISSN 0022-2372. JSTOR 1374306.

- ^ "Canis lupus irremotus Goldman, 1937". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 445-49

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 434-35

- ^ "Wolf in Newfoundland probably made it to island on ice, experts say". The Telegram. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "Genetic Retesting of DNA Confirms Second Wolf on Island of Newfoundland". Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 453-55

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 437-41

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Wilson, Paul J; Grewal, Sonya; Lawford, Ian D; Heal, Jennifer NM; Granacki, Angela G; Pennock, David; Theberge, John B; Theberge, Mary T; Voigt, Dennis R; Waddell, Will; Chambers, Robert E; Paquet, Paul C; Goulet, Gloria; Cluff, Dean; White, Bradley N (2000). "DNA profiles of the eastern Canadian wolf and the red wolf provide evidence for a common evolutionary history independent of the gray wolf". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 78 (#12): 2156. doi:10.1139/z00-158.

- ^ Wilson, Paul J.; Rutledge, Linda Y. (5 June 2021). "Considering Pleistocene North American wolves and coyotes in the eastern Canis origin story". Ecology and Evolution. 11 (13). Wiley Online Library: 9137–9147. Bibcode:2021EcoEv..11.9137W. doi:10.1002/ece3.7757. PMC 8258226. PMID 34257949.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 474-76

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 476-77

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 424-27

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Nowak, R.M. 1983. A perspective on the taxonomy of wolves in North America. In: Carbyn, L.N., ed. Wolves in Canada and Alaska. Canadian Wildlife Service, Report Series 45:lO-19.

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Miller Jr., Gerrit S. (8 June 1912). "THE NAMES OF THE LARGE WOLVES OF NORTHERN AND WESTERN NORTH AMERICA" (PDF). Smithsonian Research Online. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ Mech, L. David (1981), The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 352-353, ISBN 0-8166-1026-6

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 441-45

- ^ Mech, L. (1970). "Appendix A – Subspecies of wolves – North American". The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-307-81913-0.

Great Plains wolf; buffalo wolf; loafer. This is another extinct subspecies. It once extended throughout the Great Plains from southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan southward to northern Texas.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Wydeven, Adrian P; Van Deelen, Timothy R; Heske, Edward J, eds. (2009). Recovery of Gray wolves in the Great Lakes Region of the United States, An Endangered Subpecies Success Story. link.springer.com. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-85952-1. ISBN 978-0-387-85951-4. S2CID 132793403.

- ^ "Red Wolf" (PDF). canids.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17.

- ^ "Red wolf". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- ^ Mech, L. David (1981), The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species, University of Minnesota Press, p. 353, ISBN 0-8166-1026-6

- ^ Miller, G. S. (1913). "The names of the large wolves of northern and western North America". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 59 (#15).

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ a b c Boudadi-Maligne, Myriam (2012). "Une nouvelle sous-espèce de loup (Canis lupus maximus nov. Subsp.) dans le Pléistocène supérieur d'Europe occidentale [A new subspecies of wolf (Canis lupus maximus nov. subsp.) from the upper Pleistocene of Western Europe]". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (7): 475. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.04.003.

- ^ Goldfuss, G. A. (1823). "5-Ueber den Hölenwolf (Canis spelaeus) (About the Cave wolf)". Osteologische Beiträge zur Kenntniss verschiedener Säugethiere der Vorwelt (Osteological contributions to different knowledge Beast of the ancients). Vol. 3. Nova Acta Physico-Medica Academiea Caesarae Leopoldino-Carolinae Naturae Curiosorum. pp. 451–455.

- ^ Diedrich, Cajus G. (2015). Famous Planet Earth Caves: Sophie's Cave (Germany) - A Late Pleistocene Cave Bear Den. Vol. 1. Bentham Books. ISBN 978-1-68108-001-7. ebook - eISBN 978-1-68108-000-0

- ^ Baryshnikov, Gennady F.; Mol, Dick; Tikhonov, Alexei N (2009). "Finding of the Late Pleistocene carnivores in Taimyr Peninsula (Russia, Siberia) with paleoecological context". Russian Journal of Theriology. 8 (2): 107–113. doi:10.15298/rusjtheriol.08.2.04. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Berte, E.; Pandolfi, L. (2014). "Canis lupus (Mammalia, Canidae) from the Late Pleistocene deposit of Avetrana (Taranto, Southern Italy)". Rivista Italiana di Paleontoligia e Stratigrafia. 120 (3): 367–379.

- ^ "Canis lupus alces Goldman, 1941". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 422-24

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 435-36

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 472-74

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ "The Wolf", Alsatian Shepalute's: A New Breed for a New Millennium by Lois Denny, AuthorHouse, 2004, Pg. 42

- ^ Klinkenberg, Jeff, "For saving the Florida panther, it's desperation time", St. Petersburg Times, February 11, 1990

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 455-8

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Ishiguro, Naotaka; Inoshima, Yasuo; Shigehara, Nobuo; Ichikawa, Hideo; Kato, Masaru (2010). "Osteological and Genetic Analysis of the Extinct Ezo Wolf (Canis Lupus Hattai) from Hokkaido Island, Japan". Zoological Science. 27 (#4): 320–4. doi:10.2108/zsj.27.320. PMID 20377350. S2CID 11569628.

- ^ Nowak, R.M. 1995. Another look at wolf taxonomy. Pages 375-397 in L.H. Carbyn, S.H. Fritts, D.R. Seip, editors. Ecology and Conservation of Wolves in a Changing World. Canadian Circumpolar Institute, Edmonton, Canada.[1] (refer to page 396)

- ^ a b c Walker, Brett (2008). The Lost Wolves of Japan. University of Washington Press.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Shigehara N, Hongo H (2000) Dog and wolf remains of the earliest Jomon period at Torihama site in Fukui Prefecture. Torihama-Kaizuka-Kennkyu 2: 23–40 (in Japanese)

- ^ Ishiguro, Naotaka; Inoshima, Yasuo; Shigehara, Nobuo (2009). "Mitochondrial DNA Analysis of the Japanese Wolf (Canis Lupus Hodophilax Temminck, 1839) and Comparison with Representative Wolf and Domestic Dog Haplotypes". Zoological Science. 26 (#11): 765–70. doi:10.2108/zsj.26.765. PMID 19877836. S2CID 27005517.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 463-66

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Young, Stanley P.; Goldman, Edward A. (1944). The Wolves of North America, Part II. New York, Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 466-68

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Glover, A. (1942), Extinct and vanishing mammals of the western hemisphere, with the marine species of all the oceans, American Committee for International Wild Life Protection, pp. 227-229.

- ^ Amaral, Michael; Fazio, Bud; Fain, Steven R.; Chambers, Steven M. (23 August 2012). "An Account of the Taxonomy of North American Wolves From Morphological and Genetic Analyses". North American Fauna. 77. Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Angelici, F. M. & Rossi, L., A new subspecies of grey wolf (Carnivora, Canidae), recently extinct, from Sicily, Italy, Bollettino del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona, 42, 2018 Botanica Zoologia: 03-15

- ^ a b Alvares, F.; Bogdanowicz, W.; Campbell, L.A.D.; Godinho, R.; Hatlauf, J.; Jhala, Y.V.; Kitchener, A. C.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Krofel, M.; Moehlman, P. D.; Senn, H.; Sillero-Zubiri, C.; Viranta, S.; Werhahn, G. (2019). Old World Canis spp. with taxonomic ambiguity: Workshop conclusions and recommendations, 28th–30th May 2019 (PDF) (Report). Vairão, Portugal: IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Lord, Kathryn A.; Larson, Greger; Coppinger, Raymond P.; Karlsson, Elinor K. (2020). "The History of Farm Foxes Undermines the Animal Domestication Syndrome". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 35 (2): 125–136. Bibcode:2020TEcoE..35..125L. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2019.10.011. PMID 31810775.

- ^ (in Italian) Altobello, G. (1921), Fauna dell'Abruzzo e del Molise. Mammiferi. IV. I Carnivori (Carnivora) Archived 2016-05-04 at the Wayback Machine, Colitti e Figlio, Campobasso, pp. 38-45

- ^ a b Nowak, R. M.; Federoff, N. E. (2002). "The systematic status of the Italian wolf Canis lupus". Acta Theriologica. 47 (#3): 333–338. Bibcode:2002AcTh...47..333N. doi:10.1007/bf03194151. S2CID 366077.

- ^ Wayne, R. K.; Lehman, N.; Allard, M. W.; Honeycutt, R. L. (1992). "Mitochondrial DNA Variability of the Gray Wolf: Genetic Consequences of Population Decline and Habitat Fragmentation". Conservation Biology. 6 (#4): 559–569. Bibcode:1992ConBi...6..559W. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1992.06040559.x.

- ^ Randi, E.; Lucchini, V.; Christensen, M. F.; Mucci, N.; Funk, S. M.; Dolf, G.; Loeschcke, V. (2000). "Mitochondrial DNA Variability in Italian and East European Wolves: Detecting the Consequences of Small Population Size and Hybridization". Conservation Biology. 14 (#2): 464–473. Bibcode:2000ConBi..14..464R. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.98280.x. S2CID 86614655.

- ^ V. LUCCHINI, A. GALOV and E. RANDI Evidence of genetic distinction and long-term population decline in wolves (Canis lupus) in the Italian Apennines. Molecular Ecology (2004) 13, 523–536. abstract online

- ^ Pilot, M.; et al. (2010). "Phylogeographic history of grey wolves in Europe". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10 (1): 104. Bibcode:2010BMCEE..10..104P. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-104. PMC 2873414. PMID 20409299.

- ^ "NCBI search Canis lupus italicus".

- ^ "The wolf in Spain" (PDF).

- ^ Vos, J. (2000). "Food habits and livestock depredation of two Iberian wolf packs (Canis lupus signatus) in the north of Portugal". Journal of Zoology. 251 (#4): 457–462. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00801.x.

- ^ "Canis lupus signatus".

- ^ a b Aggarwal, R. K.; Kivisild, T.; Ramadevi, J.; Singh, L. (2007). "Mitochondrial DNA coding region sequences support the phylogenetic distinction of two Indian wolf species". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 45 (#2): 163–172. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2006.00400.x.

- ^ a b Sharma, D. K.; Maldonado, J. E.; Jhala, Y. V.; Fleischer, R. C. (2004). "Ancient wolf lineages in India". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (Suppl 3): S1–S4. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0071. PMC 1809981. PMID 15101402.

- ^ a b Shrotriya, S.; Lyngdoh, S.; Habib, B. (2012). "Wolves in Trans-Himalayas: 165 years of taxonomic confusion" (PDF). Current Science. 103 (#8). Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Werhahn, G.; Senn, H.; Kaden, J.; Joshi, J.; Bhattarai, S.; Kusi, N.; Sillero-Zubiri, C.; MacDonald, D. W. (2017). "Phylogenetic evidence for the ancient Himalayan wolf: Towards a clarification of its taxonomic status based on genetic sampling from western Nepal". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (#6): 170186. Bibcode:2017RSOS....470186W. doi:10.1098/rsos.170186. PMC 5493914. PMID 28680672.

- ^ Werhahn, Geraldine; Liu, Yanjiang; Meng, Yao; Cheng, Chen; Lu, Zhi; Atzeni, Luciano; Deng, Zhixiong; Kun, Shi; Shao, Xinning; Lu, Qi; Joshi, Jyoti; Man Sherchan, Adarsh; Karmacharya, Dibesh; Kumari Chaudhary, Hemanta; Kusi, Naresh; Weckworth, Byron; Kachel, Shannon; Rosen, Tatjana; Kubanychbekov, Zairbek; Karimov, Khalil; Kaden, Jennifer; Ghazali, Muhammad; MacDonald, David W.; Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio; Senn, Helen (2020). "Himalayan wolf distribution and admixture based on multiple genetic markers". Journal of Biogeography. 47 (6): 1272–1285. Bibcode:2020JBiog..47.1272W. doi:10.1111/jbi.13824.

- ^ "Canis lupus indica".

- ^ Wang, L; Ma, Y. P.; Zhou, Q. J.; Zhang, Y. P.; Savolaimen, P.; Wang, G. D. (2016). "The geographical distribution of grey wolves (Canis lupus) in China: A systematic review". Zoological Research. 37 (6): 315–326. doi:10.13918/j.issn.2095-8137.2016.6.315. PMC 5359319. PMID 28105796.

- ^ Larson, Greger (2017). "Reconsidering the distribution of gray wolves". Zoological Research. 38 (3): 115–116. doi:10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2017.021. PMC 5460078. PMID 28585433.

- ^ Wang, Guo-Dong; Zhang, Ming; Wang, Xuan; Yang, Melinda A.; Cao, Peng; Liu, Feng; Lu, Heng; Feng, Xiaotian; Skoglund, Pontus; Wang, Lu; Fu, Qiaomei; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2019). "Genomic Approaches Reveal an Endemic Subpopulation of Gray Wolves in Southern China". iScience. 20: 110–118. Bibcode:2019iSci...20..110W. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2019.09.008. PMC 6817678. PMID 31563851.

- ^ Weckworth, Byron V.; Dawson, Natalie G.; Talbot, Sandra L.; Flamme, Melanie J.; Cook, Joseph A. (2011). "Going Coastal: Shared Evolutionary History between Coastal British Columbia and Southeast Alaska Wolves (Canis lupus)". PLOS ONE. 6 (#5): e19582. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...619582W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019582. PMC 3087762. PMID 21573241.

- ^ Schweizer, Rena M.; Vonholdt, Bridgett M.; Harrigan, Ryan; Knowles, James C.; Musiani, Marco; Coltman, David; Novembre, John; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Genetic subdivision and candidate genes under selection in North American grey wolves". Molecular Ecology. 25 (#1): 380–402. Bibcode:2016MolEc..25..380S. doi:10.1111/mec.13364. PMID 26333947. S2CID 7808556.

- ^ Schweizer, Rena M.; Robinson, Jacqueline; Harrigan, Ryan; Silva, Pedro; Galverni, Marco; Musiani, Marco; Green, Richard E.; Novembre, John; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Targeted capture and resequencing of 1040 genes reveal environmentally driven functional variation in grey wolves". Molecular Ecology. 25 (#1): 357–79. Bibcode:2016MolEc..25..357S. doi:10.1111/mec.13467. PMID 26562361. S2CID 17798894.

- ^ a b Wayne, Robert K.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2016). "Hybridization and endangered species protection in the molecular era". Molecular Ecology. 25 (#11): 2680–9. Bibcode:2016MolEc..25.2680W. doi:10.1111/mec.13642. PMID 27064931. S2CID 15939116.

- ^ "Canis lycaon".

- ^ "Canis lycaon". ASM Mammal Diversity Database. 1.5. American Society of Mammalogists. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Canis rufus".

- ^ "Canis rufus". ASM Mammal Diversity Database. 1.5. American Society of Mammalogists. Retrieved 17 September 2021.