46°18′34″N 6°4′37″E / 46.30944°N 6.07694°E

Plan of the LHC experiments and the preaccelerators. | |

| LHC experiments | |

|---|---|

| ATLAS | A Toroidal LHC Apparatus |

| CMS | Compact Muon Solenoid |

| LHCb | LHC-beauty |

| ALICE | A Large Ion Collider Experiment |

| TOTEM | Total Cross Section, Elastic Scattering and Diffraction Dissociation |

| LHCf | LHC-forward |

| MoEDAL | Monopole and Exotics Detector At the LHC |

| FASER | ForwArd Search ExpeRiment |

| SND | Scattering and Neutrino Detector |

| LHC preaccelerators | |

| p and Pb | Linear accelerators for protons (Linac 4) and lead (Linac 3) |

| (not marked) | Proton Synchrotron Booster |

| PS | Proton Synchrotron |

| SPS | Super Proton Synchrotron |

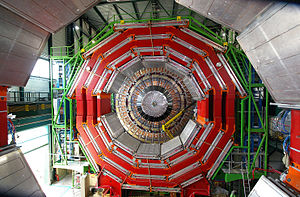

The Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment is one of two large general-purpose particle physics detectors built on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Switzerland and France. The goal of the CMS experiment is to investigate a wide range of physics, including the search for the Higgs boson, extra dimensions, and particles that could make up dark matter.

CMS is 21 metres long, 15 m in diameter, and weighs about 14,000 tonnes.[1] Over 4,000 people, representing 206 scientific institutes and 47 countries, form the CMS collaboration who built and now operate the detector.[2] It is located in a cavern at Cessy in France, just across the border from Geneva. In July 2012, along with ATLAS, CMS tentatively discovered the Higgs boson.[3][4][5] By March 2013 its existence was confirmed.[6]

Background

editRecent collider experiments such as the now-dismantled Large Electron-Positron Collider and the newly renovated Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, as well as the (as of October 2011[update]) recently closed Tevatron at Fermilab have provided remarkable insights into, and precision tests of, the Standard Model of Particle Physics. A principal achievement of these experiments (specifically of the LHC) is the discovery of a particle consistent with the Standard Model Higgs boson, the particle resulting from the Higgs mechanism, which provides an explanation for the masses of elementary particles.[7]

However, there are still many questions that future collider experiments hope to answer. These include uncertainties in the mathematical behaviour of the Standard Model at high energies, tests of proposed theories of dark matter (including supersymmetry), and the reasons for the imbalance of matter and antimatter observed in the Universe.

Physics goals

editThe main goals of the experiment are:

- to explore physics at the TeV scale

- to further study the properties of the Higgs boson, already discovered by CMS and ATLAS

- to look for evidence of physics beyond the standard model, such as supersymmetry, or extra dimensions

- to study aspects of heavy ion collisions.

The ATLAS experiment, at the other side of the LHC ring is designed with similar goals in mind, and the two experiments are designed to complement each other both to extend reach and to provide corroboration of findings. CMS and ATLAS uses different technical solutions and design of its detector magnet system to achieve the goals.

Detector summary

editCMS is designed as a general-purpose detector, capable of studying many aspects of proton collisions at 0.9–13.6 TeV, the center-of-mass energy of the LHC particle accelerator.

The CMS detector is built around a huge solenoid magnet. This takes the form of a cylindrical coil of superconducting cable that generates a magnetic field of 4 tesla, about 100 000 times that of the Earth. The magnetic field is confined by a steel 'yoke' that forms the bulk of the detector's weight at 12,500 t. An unusual feature of the CMS detector is that instead of being built in-situ underground, like the other giant detectors of the LHC experiments, it was constructed on the surface, before being lowered underground in 15 sections and reassembled.

It contains subsystems which are designed to measure the energy and momentum of photons, electrons, muons, and other products of the collisions. The innermost layer is a silicon-based tracker. Surrounding it is a scintillating crystal electromagnetic calorimeter, which is itself surrounded with a sampling calorimeter for hadrons. The tracker and the calorimetry are compact enough to fit inside the CMS solenoid, which generates a powerful magnetic field of 3.8 T. Outside the magnet are the large muon detectors, which are inside the return yoke of the magnet.

CMS by layers

editFor full technical details about the CMS detector, please see the Technical Design Report.[8]

The interaction point

editThis is the point in the centre of the detector at which proton-proton collisions occur between the two counter-rotating beams of the LHC. At each end of the detector magnets focus the beams into the interaction point. At collision each beam has a radius of 17 μm and the crossing angle between the beams is 285 μrad.

At full design luminosity each of the two LHC beams will contain 2,808 bunches of 1.15×1011 protons. The interval between crossings is 25 ns, although the number of collisions per second is only 31.6 million due to gaps in the beam as injector magnets are activated and deactivated.

At full luminosity each collision will produce an average of 20 proton-proton interactions. The collisions occur at a centre of mass energy of 8 TeV. But, it is worth noting that for studies of physics at the electroweak scale, the scattering events are initiated by a single quark or gluon from each proton, and so the actual energy involved in each collision will be lower as the total centre of mass energy is shared by these quarks and gluons (determined by the parton distribution functions).

The first test which ran in September 2008 was expected to operate at a lower collision energy of 10 TeV but this was prevented by the 19 September 2008 shutdown. When at this target level, the LHC will have a significantly reduced luminosity, due to both fewer proton bunches in each beam and fewer protons per bunch. The reduced bunch frequency does allow the crossing angle to be reduced to zero however, as bunches are far enough spaced to prevent secondary collisions in the experimental beampipe.

Layer 1 – The tracker

editMomentum of particles is crucial in helping us to build up a picture of events at the heart of the collision. One method to calculate the momentum of a particle is to track its path through a magnetic field; the more curved the path, the less momentum the particle had. The CMS tracker records the paths taken by charged particles by finding their positions at a number of key points.

The tracker can reconstruct the paths of high-energy muons, electrons and hadrons (particles made up of quarks) as well as see tracks coming from the decay of very short-lived particles such as beauty or "b quarks" that will be used to study the differences between matter and antimatter.

The tracker needs to record particle paths accurately yet be lightweight so as to disturb the particle as little as possible. It does this by taking position measurements so accurate that tracks can be reliably reconstructed using just a few measurement points. Each measurement is accurate to 10 μm, a fraction of the width of a human hair. It is also the inner most layer of the detector and so receives the highest volume of particles: the construction materials were therefore carefully chosen to resist radiation.[9]

The CMS tracker is made entirely of silicon: the pixels, at the very core of the detector and dealing with the highest intensity of particles, and the silicon microstrip detectors that surround it. As particles travel through the tracker the pixels and microstrips produce tiny electric signals that are amplified and detected. The tracker employs sensors covering an area the size of a tennis court, with 75 million separate electronic read-out channels: in the pixel detector there are some 6,000 connections per square centimetre.

The CMS silicon tracker consists of 14 layers in the central region and 15 layers in the endcaps. The innermost four layers (up to 16 cm radius) consist of 100 × 150 μm pixels, 124 million in total. The pixel detector was upgraded as a part of the CMS phase-1 upgrade in 2017, which added an additional layer to both the barrel and endcap, and shifted the innermost layer 1.5 cm closer to the beamline. [10]

The next four layers (up to 55 cm radius) consist of 10 cm × 180 μm silicon strips, followed by the remaining six layers of 25 cm × 180 μm strips, out to a radius of 1.1 m. There are 9.6 million strip channels in total.

During full luminosity collisions the occupancy of the pixel layers per event is expected to be 0.1%, and 1–2% in the strip layers. The expected HL-LHC upgrade will increase the number of interactions to the point where over-occupancy would significantly reduce track-finding effectiveness. An upgrade is planned to increase the performance and the radiation tolerance of the tracker.

This part of the detector is the world's largest silicon detector. It has 205 m2 of silicon sensors (approximately the area of a tennis court) in 9.3 million microstrip sensors comprising 76 million channels.[11]

Layer 2 – The Electromagnetic Calorimeter

editThe Electromagnetic Calorimeter (ECAL) is designed to measure with high accuracy the energies of electrons and photons.

The ECAL is constructed from crystals of lead tungstate, PbWO4. This is an extremely dense but optically clear material, ideal for stopping high energy particles. Lead tungstate crystal is made primarily of metal and is heavier than stainless steel, but with a touch of oxygen in this crystalline form it is highly transparent and scintillates when electrons and photons pass through it. This means it produces light in proportion to the particle's energy. These high-density crystals produce light in fast, short, well-defined photon bursts that allow for a precise, fast and fairly compact detector. It has a radiation length of χ0 = 0.89 cm, and has a rapid light yield, with 80% of light yield within one crossing time (25 ns). This is balanced however by a relatively low light yield of 30 photons per MeV of incident energy. The crystals used have a front size of 22 mm × 22 mm and a depth of 230 mm. They are set in a matrix of carbon fibre to keep them optically isolated, and backed by silicon avalanche photodiodes for readout.

The ECAL, made up of a barrel section and two "endcaps", forms a layer between the tracker and the HCAL. The cylindrical "barrel" consists of 61,200 crystals formed into 36 "supermodules", each weighing around three tonnes and containing 1,700 crystals. The flat ECAL endcaps seal off the barrel at either end and are made up of almost 15,000 further crystals.

For extra spatial precision, the ECAL also contains pre-shower detectors that sit in front of the endcaps. These allow CMS to distinguish between single high-energy photons (often signs of exciting physics) and the less interesting close pairs of low-energy photons.

At the endcaps the ECAL inner surface is covered by the pre-shower subdetector, consisting of two layers of lead interleaved with two layers of silicon strip detectors. Its purpose is to aid in pion-photon discrimination.

Layer 3 – The Hadronic Calorimeter

editThe Hadron Calorimeter (HCAL) measures the energy of hadrons, particles made of quarks and gluons (for example protons, neutrons, pions and kaons). Additionally it provides indirect measurement of the presence of non-interacting, uncharged particles such as neutrinos.

The HCAL consists of layers of dense material (brass or steel) interleaved with tiles of plastic scintillators, read out via wavelength-shifting fibres by hybrid photodiodes. This combination was determined to allow the maximum amount of absorbing material inside of the magnet coil.

The high pseudorapidity region is instrumented by the Hadronic Forward (HF) detector. Located 11 m either side of the interaction point, this uses a slightly different technology of steel absorbers and quartz fibres for readout, designed to allow better separation of particles in the congested forward region. The HF is also used to measure the relative online luminosity system in CMS.

About half of the brass used in the endcaps of the HCAL used to be Russian artillery shells.[12]

Layer 4 – The magnet

editThe CMS magnet is the central device around which the experiment is built, with a 4 Tesla magnetic field that is 100,000 times stronger than the Earth's. CMS has a large solenoid magnet. This allows the charge/mass ratio of particles to be determined from the curved track that they follow in the magnetic field. It is 13 m long and 6 m in diameter, and its refrigerated superconducting niobium-titanium coils were originally intended to produce a 4 T magnetic field. The operating field was scaled down to 3.8 T instead of the full design strength in order to maximize longevity.[13]

The inductance of the magnet is 14 Η and the nominal current for 4 T is 19,500 A, giving a total stored energy of 2.66 GJ, equivalent to about half-a-tonne of TNT. There are dump circuits to safely dissipate this energy should the magnet quench. The circuit resistance (essentially just the cables from the power converter to the cryostat) has a value of 0.1 mΩ which leads to a circuit time constant of nearly 39 hours. This is the longest time constant of any circuit at CERN. The operating current for 3.8 T is 18,160 A, giving a stored energy of 2.3 GJ.

The job of the big magnet is to bend the paths of particles emerging from high-energy collisions in the LHC. The more momentum a particle has the less its path is curved by the magnetic field, so tracing its path gives a measure of momentum. CMS began with the aim of having the strongest magnet possible because a higher strength field bends paths more and, combined with high-precision position measurements in the tracker and muon detectors, this allows accurate measurement of the momentum of even high-energy particles.

The tracker and calorimeter detectors (ECAL and HCAL) fit snugly inside the magnet coil whilst the muon detectors are interleaved with a 12-sided iron structure that surrounds the magnet coils and contains and guides the field. Made up of three layers this "return yoke" reaches out 14 metres in diameter and also acts as a filter, allowing through only muons and weakly interacting particles such as neutrinos. The enormous magnet also provides most of the experiment's structural support, and must be very strong itself to withstand the forces of its own magnetic field.

Layer 5 – The muon detectors and return yoke

editAs the name "Compact Muon Solenoid" suggests, detecting muons is one of CMS's most important tasks. Muons are charged particles that are just like electrons and positrons, but are 200 times more massive. We expect them to be produced in the decay of a number of potential new particles; for instance, one of the clearest "signatures" of the Higgs Boson is its decay into four muons.

Because muons can penetrate several metres of iron without depositing a significant amount of energy, unlike most particles, they are not stopped by any of CMS's calorimeters. Therefore, chambers to detect muons are placed at the very edge of the experiment where they are the only particles likely to register a signal.

To identify muons and measure their momenta, CMS uses three types of detector: drift tubes (DT), cathode strip chambers (CSC), resistive plate chambers (RPC), and Gas electron multiplier (GEM). The DTs are used for precise trajectory measurements in the central barrel region, while the CSCs are used in the end caps. The RPCs provide a fast signal when a muon passes through the muon detector, and are installed in both the barrel and the end caps.

The drift tube (DT) system measures muon positions in the barrel part of the detector. Each 4-cm-wide tube contains a stretched wire within a gas volume. When a muon or any charged particle passes through the volume it knocks electrons off the atoms of the gas. These follow the electric field ending up at the positively charged wire. By registering where along the wire electrons hit (in the diagram, the wires are going into the page) as well as by calculating the muon's original distance away from the wire (shown here as horizontal distance and calculated by multiplying the speed of an electron in the tube by the time taken) DTs give two coordinates for the muon's position. Each DT chamber, on average 2 m x 2.5 m in size, consists of 12 aluminium layers, arranged in three groups of four, each with up to 60 tubes: the middle group measures the coordinate along the direction parallel to the beam and the two outside groups measure the perpendicular coordinate.

Cathode strip chambers (CSC) are used in the endcap disks where the magnetic field is uneven and particle rates are high. CSCs consist of arrays of positively charged "anode" wires crossed with negatively charged copper "cathode" strips within a gas volume. When muons pass through, they knock electrons off the gas atoms, which flock to the anode wires creating an avalanche of electrons. Positive ions move away from the wire and towards the copper cathode, also inducing a charge pulse in the strips, at right angles to the wire direction. Because the strips and the wires are perpendicular, we get two position coordinates for each passing particle. In addition to providing precise space and time information, the closely spaced wires make the CSCs fast detectors suitable for triggering. Each CSC module contains six layers making it able to accurately identify muons and match their tracks to those in the tracker.

Resistive plate chambers (RPC) are fast gaseous detectors that provide a muon trigger system parallel with those of the DTs and CSCs. RPCs consist of two parallel plates, a positively charged anode and a negatively charged cathode, both made of a very high resistivity plastic material and separated by a gas volume. When a muon passes through the chamber, electrons are knocked out of gas atoms. These electrons in turn hit other atoms causing an avalanche of electrons. The electrodes are transparent to the signal (the electrons), which are instead picked up by external metallic strips after a small but precise time delay. The pattern of hit strips gives a quick measure of the muon momentum, which is then used by the trigger to make immediate decisions about whether the data are worth keeping. RPCs combine a good spatial resolution with a time resolution of just one nanosecond (one billionth of a second).

Gas electron multiplier (GEM) detectors represent a new muon system in CMS, in order to complement the existing systems in the endcaps. The forward region is the part of CMS most affected by large radiation doses and high event rates. The GEM chambers will provide additional redundancy and measurement points, allowing a better muon track identification and also wider coverage in the very forward region. The CMS GEM detectors are made of three layers, each of which is a 50 μm thick copper-cladded polyimide foil. These chambers are filled with an Ar/CO2 gas mixture, where the primary ionisation due to incident muons will occur which subsequently result in an electron avalanche, providing an amplified signal.[14]

Collecting and collating the data

editPattern recognition

editNew particles discovered in CMS will be typically unstable and rapidly transform into a cascade of lighter, more stable and better understood particles. Particles travelling through CMS leave behind characteristic patterns, or "signatures", in the different layers, allowing them to be identified. The presence (or not) of any new particles can then be inferred.

Trigger system

editTo have a good chance of producing a rare particle, such as a Higgs boson, a very large number of collisions is required. Most collision events in the detector are "soft" and do not produce interesting effects. The amount of raw data from each crossing is approximately 1 megabyte, which at the 40 MHz crossing rate would result in 40 terabytes of data a second, an amount that the experiment cannot hope to store, let alone process properly. The full trigger system reduces the rate of interesting events down to a manageable 1,000 per second.

To accomplish this, a series of "trigger" stages are employed. All the data from each crossing is held in buffers within the detector while a small amount of key information is used to perform a fast, approximate calculation to identify features of interest such as high energy jets, muons or missing energy. This "Level 1" calculation is completed in around 1 μs, and event rate is reduced by a factor of about 1,000 down to 50 kHz. All these calculations are done on fast, custom hardware using reprogrammable field-programmable gate arrays (FPGA).

If an event is passed by the Level 1 trigger all the data still buffered in the detector is sent over fibre-optic links to the "High Level" trigger, which is software (mainly written in C++) running on ordinary computer servers. The lower event rate in the High Level trigger allows time for much more detailed analysis of the event to be done than in the Level 1 trigger. The High Level trigger reduces the event rate by a further factor of 100 down to 1,000 events per second. These are then stored on tape for future analysis.

Data analysis

editData that has passed the triggering stages and been stored on tape is duplicated using the Grid to additional sites around the world for easier access and redundancy. Physicists are then able to use the Grid to access and run their analyses on the data.

There are a huge range of analyses performed at CMS, including:

- Performing precision measurements of Standard Model particles, which allows both for furthering the knowledge of these particles and also for the collaboration to calibrate the detector and measure the performance of various components.

- Searching for events with large amounts of missing transverse energy, which implies the presence of particles that have passed through the detector without leaving a signature. In the Standard Model only neutrinos would traverse the detector without being detected but a wide range of Beyond the Standard Model theories contain new particles that would also result in missing transverse energy.

- Studying the kinematics of pairs of particles produced by the decay of a parent, such as the Z boson decaying to a pair of electrons or the Higgs boson decaying to a pair of tau leptons or photons, to determine various properties and mass of the parent.

- Looking at jets of particles to study the way the partons (quarks and gluons) in the collided protons have interacted, or to search for evidence of new physics that manifests in hadronic final states.

- Searching for high particle multiplicity final states (predicted by many new physics theories) is an important strategy because common Standard Model particle decays very rarely contain a large number of particles, and those processes that do are well understood.

Milestones

edit| 1998 | Construction of surface buildings for CMS begins. |

| 2000 | LEP shut down, construction of cavern begins. |

| 2004 | Cavern completed. |

| 10 September 2008 | First beam in CMS. |

| 23 November 2009 | First collisions in CMS. |

| 30 March 2010 | First 7 TeV proton-proton collisions in CMS. |

| 7 November 2010 | First lead ion collisions in CMS.[15] |

| 5 April 2012 | First 8 TeV proton-proton collisions in CMS.[16] |

| 29 April 2012 | Announcement of the 2011 discovery of the first new particle generated here, the excited neutral Xi-b baryon. |

| 4 July 2012 | Spokesperson Joe Incandela (UC Santa Barbara) announced evidence for a particle at about 125 GeV at a seminar and webcast. This is "consistent with the Higgs boson". Further updates in the following years confirmed that the newly discovered particle is the Higgs boson.[17] |

| 16 February 2013 | End of the LHC 'Run 1' (2009–2013).[18] |

| 3 June 2015 | Beginning of the LHC 'Run 2' with an increased collision energy of 13 TeV.[19] |

| 28 August 2018 | Observation of the Higgs Boson decaying to a bottom quark pair.[20] |

| 3 December 2018 | End of the LHC 'Run 2' and beginning of Long Shutdown 2.[21] |

| 3 March 2021 | End of CERN Long Shutdown 2.[22] |

| March-April 2022 | Beginning of LHC 'Run 3' with an increased collision energy of 13.6 TeV.[23] |

| 25 November 2024 | Planned end of 2024 run.[23] |

| 2025 | Planned start of Long Shutdown 3 and HL-LHC Installation.[24] |

| 2028 | Planned end of Long Shutdown 3 and beginning of 'Run 4'.[24] |

-

Computer-generated event display of protons hitting a tungsten block just upstream of CMS on the first beam day, September 2008

Etymology

editThe term Compact Muon Solenoid comes from the relatively compact size of the detector, the fact that it detects muons, and the use of solenoids in the detector.[25] "CMS" is also a reference to the center-of-mass system, an important concept in particle physics.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2014-10-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "CMS Collaboration - CMS Experiment". cms.cern. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ Biever, C. (6 July 2012). "It's a boson! But we need to know if it's the Higgs". New Scientist. Retrieved 2013-01-09.

'As a layman, I would say, I think we have it,' said Rolf-Dieter Heuer, director general of CERN at Wednesday's seminar announcing the results of the search for the Higgs boson. But when pressed by journalists afterwards on what exactly 'it' was, things got more complicated. 'We have discovered a boson – now we have to find out what boson it is'

Q: 'If we don't know the new particle is a Higgs, what do we know about it?' We know it is some kind of boson, says Vivek Sharma of CMS [...]

Q: 'are the CERN scientists just being too cautious? What would be enough evidence to call it a Higgs boson?' As there could be many different kinds of Higgs bosons, there's no straight answer.

[emphasis in original] - ^

Siegfried, T. (20 July 2012). "Higgs Hysteria". Science News. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

In terms usually reserved for athletic achievements, news reports described the finding as a monumental milestone in the history of science.

- ^

Del Rosso, A. (19 November 2012). "Higgs: The beginning of the exploration". CERN Bulletin. Retrieved 2013-01-09.

Even in the most specialized circles, the new particle discovered in July is not yet being called the "Higgs boson". Physicists still hesitate to call it that before they have determined that its properties fit with those the Higgs theory predicts the Higgs boson has.

- ^ O'Luanaigh, C. (14 March 2013). "New results indicate that new particle is a Higgs boson". CERN. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ^ "The Higgs Boson". CERN: Accelerating Science. CERN. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ Acosta, Darin (2006). CMS Physics: Technical Design Report Volume 1: Detector Performance and Software. Technical design report. CMS. ISBN 9789290832683.

- ^ "Tracker detector - CMS Experiment". cms.web.cern.ch. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Weber, Hannsjorg (2016). "The phase-1 upgrade of the CMS pixel detector". 2016 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium, Medical Imaging Conference and Room-Temperature Semiconductor Detector Workshop (NSS/MIC/RTSD). pp. 1–4. doi:10.1109/NSSMIC.2016.8069719. ISBN 978-1-5090-1642-6. OSTI 1475062. S2CID 22786095.

- ^ CMS installs the world's largest silicon detector, CERN Courier, Feb 15, 2008

- ^ "Using Russian navy shells - CMS Experiment". cms.web.cern.ch. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Precise mapping of the magnetic field in the CMS barrel yoke using cosmic rays

- ^ "Detector". cms.cern. Archived from the original on 2021-02-19. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

- ^ "First lead-ion collisions in the LHC". CERN. 2010. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ^ "New world record - first pp collisions at 8 TeV". CERN. 2012. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ^ "ATLAS and CMS experiments shed light on Higgs properties". CERN. 2015. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

...the decay of the Higgs boson to tau particles is now observed with more than 5 sigma significance...

- ^ "LHC report: Run 1 - the final flurry". CERN. 2013. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ^ "LHC experiments back in business at record energy". CERN. 2015. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ "LHC Schedule 2018" (PDF). CERN. 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ "Long-sought decay of Higgs boson observed". CERN. 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ "MASTER SCHEDULE OF THE LONG SHUTDOWN 2 (2019-2020)" (PDF). CERN. 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ a b "Accelerator Report: The LHC is well ahead of schedule". CERN. 2024-07-18. Retrieved 2024-07-24.

- ^ a b "LS3 schedule change | High Luminosity LHC Project". hilumilhc.web.cern.ch. Retrieved 2024-07-24.

- ^ Aczel, Ammir D. "Present at the Creation: Discovering the Higgs Boson". Random House, 2012

References

edit- CMS Collaboration (Bayatian, G.L. et al.) (2006). "CMS Physics Technical Design Report Volume I: Software and Detector Performance" (PDF). CERN.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) (mirrors: inspire, CDS)

External links

edit- CMS home page

- CMS experiment record in INSPIRE-HEP

- CMS Public Results

- CMS Outreach

- CMS Times Archived 2008-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

- CMS section from US/LHC Website

- The assembly of the CMS detector, step by step, through a 3D animation

- The CMS Collaboration, S Chatrchyan; et al. (2008-08-14). "The CMS experiment at the CERN LHC". Journal of Instrumentation. 3 (8): S08004. Bibcode:2008JInst...3S8004C. doi:10.1088/1748-0221/3/08/S08004. hdl:10067/730480151162165141. (Full design documentation)

- Copeland, Ed. "Inside the CMS Experiment". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.