Bunny Lake Is Missing is a 1965 psychological mystery film directed and produced by Otto Preminger and starring Carol Lynley, Keir Dullea and Laurence Olivier.[3] Filmed in black-and-white widescreen format in London, it was based on the 1957 novel Bunny Lake Is Missing by Merriam Modell. The score is by Paul Glass. The rock band the Zombies also appear in the film.

| Bunny Lake Is Missing | |

|---|---|

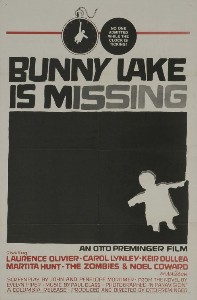

Film poster designed by Saul Bass | |

| Directed by | Otto Preminger |

| Screenplay by | John Mortimer Penelope Mortimer |

| Based on | Bunny Lake Is Missing by Merriam Modell |

| Produced by | Otto Preminger |

| Starring | Laurence Olivier Carol Lynley Keir Dullea Martita Hunt The Zombies Noël Coward |

| Cinematography | Denys N. Coop |

| Edited by | Peter Thornton |

| Music by | Paul Glass |

| Color process | Black and white |

Production company | Wheel Productions |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States[1][2] |

| Language | English |

Plot

editAmerican single mother Ann Lake, who recently moved to London from New York, arrives at the Little People's Garden pre-school to collect her daughter, Bunny. The child has mysteriously disappeared. An administrator recalls meeting Ann but claims never to have seen the missing child. Ann and her brother Steven search the school and find a peculiar old woman living upstairs, who claims she collects children's nightmares. In desperation, the Lakes call the police and Superintendent Newhouse arrives on the scene. Everyone becomes a suspect and Superintendent Newhouse is steadfast, diligently following every lead. The police and Newhouse decide to visit the Lakes' new residence.

They conclude that all of Bunny's possessions have been removed from the Lakes' new home. Ann cannot understand why anyone would do this and reacts emotionally. Superintendent Newhouse begins to suspect that Bunny Lake does not exist, after he learns that "Bunny" was the name of Ann's imaginary childhood friend. Ann's landlord, an aging actor, attempts to seduce her. Steven argues with Newhouse, angrily tells him that he will hire a private detective to find Bunny, and storms off. Newhouse decides to become better acquainted with Ann to learn more about Bunny. He takes her to a local pub where he plies her with brandy and soda.

On her return home, Ann discovers she still has the claim ticket for Bunny's doll, which was taken to a doll hospital for repairs. Regarding the doll as proof of Bunny's existence, she frantically rushes to the doll hospital late at night and retrieves the doll. Steven arrives later and when Ann shows him the doll, Steven burns the doll, hoping to destroy it, then knocks Ann unconscious. He takes Ann to a hospital and tells the desk nurse that Ann has been hallucinating about a missing girl who does not exist. Ann is put under observation with instructions for her to be sedated if she awakes.

Ann wakes up in the hospital and escapes. She discovers that Steven is burying Bunny's possessions in the garden, and had sedated the little girl, hiding her in the trunk of his Sunbeam Tiger car. Steven implies an incestuous interest with his sister, complaining that Bunny has always come between them. Believing that Ann loves Bunny more than him, the child threatens Steven's dream of a future with his sister. Ann, realising her brother is insane, begins playing childhood games with Steven, in order to distract him from killing Bunny. Newhouse, having discovered that Steven lied to the police about the name of the ship that brought the Lakes to England, rushes quickly to the Lakes' residence, arriving in time to apprehend Steven, successfully rescuing Ann and Bunny.

Cast

edit- Laurence Olivier as Newhouse

- Carol Lynley as Ann

- Keir Dullea as Steven

- Martita Hunt as Ada Ford

- Anna Massey as Elvira

- Clive Revill as Andrews

- Finlay Currie as the doll maker

- Lucie Mannheim as the cook

- The Zombies as themselves

- Noël Coward as Wilson

In addition, Bunny Lake is played by Suky Appleby.

Production

editDevelopment

editPreminger had found the novel's denouement lacking in credibility, so he changed the identity of the would-be murderer. This prompted many rewrites from his British husband-and-wife scriptwriters John Mortimer and Penelope Mortimer before Preminger was satisfied.[4]

Filming

editAdapting the original novel,[5] Preminger moved the story from New York to London, where he liked working. His dark, sinister vision of London made use of many real locations: the Barry Elder Doll Museum in Hammersmith stood in for the dolls' hospital;[6] the Little People's Garden School used school buildings in Hampstead; and the "Frogmore End" house was Cannon Hall, which had belonged to novelist Daphne du Maurier's father Sir Gerald du Maurier. The 1965 Sunbeam Tiger sports car (registration EDU 296C) featured in this film still exists as a classic car, and sold at auction for £35,840 (2015).

Post-production

editThe opening title sequences and poster were done by graphic designer Saul Bass.[7]

English rock band the Zombies are featured in the credits and on the film's poster for their contribution of three songs to the film's soundtrack: "Remember You", "Just Out of Reach" and "Nothing's Changed". The band is featured performing on a television in the pub where Superintendent Newhouse meets with Ann, and "Just Out of Reach" plays on a janitor's radio as Ann escapes from the hospital. With Preminger present in the studio, the band recorded a two-minute radio ad set to the tune of "Just Out of Reach" that promoted the film's release and urged audiences to "Come on time!" in keeping with the film's no-late-admissions policy. These efforts represent an early instance of what became the common Hollywood practice of promotional tie-ins with popular musical acts.[8]

Release

editPromotion

editAs with Psycho (1960), audiences were not admitted after the film's start. This was not common practice at the time and was emphasised in the film's promotion, including on the poster, which warned: "No One Admitted While the Clock Is Ticking!"

Critical reception

editThe Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "This is Preminger with the fat of the blockbusters pared away. The opening is beautifully organised, getting well into the action before revealing just what it's all about, modulating from the hustle of things being done in a hurry (removal men; taxi rides; the return to the school, with the staircase thronged with chattering mothers) into the arrival of police cars, dogs and search parties. Preminger keeps his camera thrusting forward, dodging round corners, pushing through crowds; doors open on to dark interiors, lights are snapped suddenly on. ...Where Bunny Lake falters is in the transition from sharp whodunnit to psychiatric shocker."[9]

Andrew Sarris wrote in The Village Voice that the film's "plot collapses ... because there is no overriding social interest at stake, but rather an implausibly elaborate caper by a conveniently psychotic character," and added that although the "movie is a pleasure to watch from beginning to end ...] there are really no characters to consider in Preminger's chilling world of doors and dolls and deceits and degeneracies of decor."[10]

Variety described it as "an entertaining, fast-paced exercise in the exploration of a sick mind," with Lynley "carrying much of the film on her shoulders."[11]

Writing in The New York Times, critic Bosley Crowther reported that "conspicuously absent from this grossly calculated attempt at a psychological mystery thriller is just plain common sense – the kind of simple deductive logic that any reasonably intelligent person would use."[12]

Leslie Halliwell said: "A nightmarish gimmick story, with more gimmicks superimposed along the way to say nothing of a Pyshcoish ending; some of the decoration works and makes the unconvincing story compelling, while the cast is alone worth the price of admission."[13]

Home media

editThe film was released on DVD in 2005 (Region 1) and 2007 (Region 2). In 2014, Twilight Time released a limited Blu-ray edition.[14][15] In 2019 Powerhouse Films & Indicator released a Blu-ray edition with many special features included.

In popular culture

editThe film was spoofed in Mad magazine, in the April 1966 issue (#102), under the title "Bubby Lake Missed by a Mile".[16] In the Better Call Saul episode "Off Brand", Chuck McGill walks past a movie theatre playing Bunny Lake is Missing. It is reminiscent of the urban legend the Vanishing Hotel Room.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ Gateway Film Center

- ^ The Colonial Theatre

- ^ "Bunny Lake Is Missing". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Foster Hirsch, "Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King" (2007).

- ^ Maria DiBattista (Princeton University): "Afterword". In: Evelyn Piper: Bunny Lake Is Missing (Femmes Fatales: Women Write Pulp) (The Feminist Press at The City University of New York: New York, 2004) 198-219 (ISBN 1-55861-474-5) (includes a discussion of the differences between Piper's novel and Preminger's film version)

- ^ "Dolls' Surgeon".

- ^ Bunny Lake is Missing (1965) — Art of the Title

- ^ Alec Palao (1997). "Begin Here and Singles" and "In the Studio Rare and Unissued". In Zombie Heaven (pp. 46–47 & 58) [CD booklet]. London: Big Beat Records.

- ^ "Bunny Lake Is Missing". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 33 (384): 35. 1 January 1966 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (21 October 1965). "Films". The Village Voice.

- ^ "Bunny Lake is Missing". Variety. Variety Media LLC. 31 December 1964. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (5 October 1965). "The screen: Bunny Lake is Missing". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Halliwell, Leslie (1989). Halliwell's Film Guide (7th ed.). London: Paladin. p. 155. ISBN 0586088946.

- ^ Twilight Time

- ^ Home Theater Forum, Blu-ray

- ^ "Doug Gilford's Mad Cover Site - Mad #102". madcoversite.com.