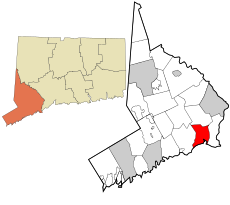

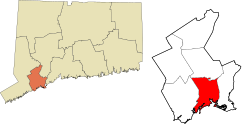

Bridgeport is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Connecticut[7] and the fifth-most populous city in New England, with a population of 148,654 in 2020.[3] Located in eastern Fairfield County at the mouth of the Pequonnock River on Long Island Sound, it is a port city 60 miles (97 km) from Manhattan and 40 miles (64 km) from The Bronx. It borders the towns of Trumbull to the north, Fairfield to the west, and Stratford to the east. Bridgeport and other towns in Fairfield County make up the Greater Bridgeport Planning Region, as well as the Bridgeport–Stamford–Norwalk–Danbury metropolitan statistical area, the second largest metropolitan area in Connecticut. The Bridgeport–Stamford–Norwalk–Danbury metropolis forms part of the New York metropolitan area.

Bridgeport | |

|---|---|

| Nicknames: The Park City, BPT[1] | |

Mottoes:

| |

| Coordinates: 41°11′11″N 73°11′44″W / 41.18639°N 73.19556°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Connecticut |

| County | Fairfield |

| Region | CT Metropolitan |

| MSA | Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk |

| CSA | New York |

| Incorporated (town) | 1821 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1836 |

| Named for | A drawbridge over the Pequonnock River |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Joseph P. Ganim (D) |

| Area | |

• City | 19.4 sq mi (50.2 km2) |

| • Land | 16.0 sq mi (41.4 km2) |

| • Water | 3.4 sq mi (8.8 km2) |

| • Urban | 397.29 sq mi (1,029.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 3 ft (1 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 148,654 |

| • Rank | US: 172nd |

| • Density | 9,290.875/sq mi (3,587.228/km2) |

| • Urban | 916,408 (US: 51st) |

| • Urban density | 2,306.6/sq mi (890.6/km2) |

| • Metro | 939,904 (US: 57th) |

| Demonym | Bridgeporter |

| GDP | |

| • Bridgeport (MSA) | $104.368 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Codes | 06601–06602, 06604–06608, 06610, 06650, 06673, 06699[6] |

| Area code(s) | 203/475 |

| FIPS code | 09-08000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 205720 |

| Airport | Sikorsky Memorial Airport |

| Major highways | |

| Commuter rail | |

| Website | bridgeportct |

Inhabited by the Paugussett Native American tribe until English settlement in the 1600s, Bridgeport was incorporated in 1821 as a town, and as a city in 1836. Showman P. T. Barnum was a resident of the city and served as the town's mayor (1871).[8] Barnum built four houses in Bridgeport and housed his circus in town during winter. The city in the early 20th century saw an economic and population boom, becoming by all measures Connecticut's chief manufacturing city by 1905.[9] Bridgeport was the site of the world's first mutual telephone exchange (1877),[10] the first dental hygiene school (1949),[11] and the first bank telephone bill service in the US (1981).[12] Inventor Harvey Hubbell II invented the electric plug outlet in Bridgeport in 1912.[13] The Frisbie Pie Company was founded and operated in Bridgeport.[14] The world's first Subway restaurant opened in the city's North End in 1965.[15] After World War II, industrial restructuring and suburbanization caused the loss of many large companies and affluent residents, leaving Bridgeport struggling with issues of poverty and violent crime.[16]

Since the beginning of the 21st century, Bridgeport has begun extensive redevelopment of its downtown and other neighborhoods. Bridgeport's crime rate started going down significantly around 2010; by 2018, it had been reduced by almost 50 percent.[17] Bridgeport is home to three museums,[18] the University of Bridgeport, Housatonic Community College, Paier College, and part of Sacred Heart University[19][20] as well as the state's only zoo.[21] Bridgeport is officially nicknamed "Park City", due to its 35 public parks taking up 1,300 acres, including two large ones. Although none are headquartered within the city itself, more than a dozen Fortune 500 companies are based in its metropolitan area, which it shares with Stamford. Bridgeport by various sites has been consistently ranked as among the 25 most ethnically and culturally diverse American cities.[22][23][24][25][26]

History

editBridgeport was inhabited by the Paugussett native American tribe during the start of European colonization. The earliest European communal settlement was in the historical Stratfield district,[27] along US Route 1, known in colonial times as the King's Highway. Close by, Mount Grove Cemetery was laid out on what was a native village that extended past the 1650s.[28] It is also an ancient Paugusett burial ground.

The burgeoning farming community grew and became a center of trade, shipbuilding, and whaling. The town was incorporated to subsidize the Housatonic Railroad and rapidly industrialized following the rail line's connection to the New York and New Haven railroad. The town was given its name because of the need for bridges over the Pequonnock River that provided a navigable port at the mouth of the river. Manufacturing was the mainstay of the local economy until the 1970s.

Colonial history

editThe first documented European settlement within the present city limits of Bridgeport took place in 1644, centered at Black Rock Harbor and along North Avenue between Park and Briarwood Avenues. The place was called Pequonnock[9] (Quiripi for "Cleared Land"), after a band of the Paugussett, an Algonquian-speaking Native American people who occupied this area. One of their sacred sites was Golden Hill, which overlooked the harbor and was the location of natural springs and their planting fields. (It has since been blasted through for construction of an expressway.)[29][30] The Golden Hill Indians were granted a reservation here by the Colony of Connecticut in 1639; it lasted until 1802. (One of the tribes acquired land for a small reservation in the late 19th century that was recognized by the state. It is retained in the Town of Trumbull.)

In 1639, Roger Ludlow, deputy governor of the English Connecticut Colony was ordered by the colony's General Assembly in Hartford to establish two plantations, one at Cupheg the mouth of the Housatonic River (today Stratford), and one at the harbor at the mouth of the Pequonnock River, today's Bridgeport Harbor. Ludlow disobeyed orders and instead established a settlement in Unconway (today's Fairfield), probably due to fears of the large Paugussett settlement at Golden Hill, which was a sacred site of theirs, so it is believed that they perhaps instead settled in sparsely populated land surrounding the village.[31] In 1659, the general court in Hartford established the official borders of the Paugussett Reservation.[32]

Bridgeport's early years were marked by residents' reliance on fishing and farming. This was similar to the economy of the Paugussett, who had cultivated corn, beans, and squash; and fished and gathered shellfish from both the river and sound. A village called Newfield began to develop around the corner of State and Water streets in the 1760s.[33] The area officially became known as Stratfield in 1695[9] or 1701, due to its location between the already existing towns of Stratford and Fairfield.[34] During the American Revolution, Newfield Harbor was a center of privateering.[30][9]

19th century

editBy the time of the State of Connecticut's ratification of the Articles of Confederation in 1781, many of the local farmers held shares in vessels trading at Newfield Harbor or had begun trading in their own name. Newfield initially expanded around the coasting trade with Boston, New York, and Baltimore and the international trade with the West Indies.[33][35] The commercial activity of the village was clustered around the wharves on the west bank of the Pequonnock, while the churches were erected inland on Broad Street. In 1787, the Fairfield County Court ordered the laying out and widening of what is now State Street and Main Street in downtown Bridgeport, along the Pequannock River then Newfield. It was assumed before the Revolution that this land would grow into a city.[36] [37]

"Bridgeport grew up without a plan, or in spite of one".

— Samuel Orcutt, A History of the Old Town of Stratford and the City of Bridgeport (1886), Chapter XIX

In 1800, the village became the Borough of Bridgeport,[40] the first so incorporated in the state.[41] It was named for the Newfield or Lottery Bridge across the Pequonnock, connecting the wharves on its east and west banks.[39] Bridgeport Bank was established in 1806.[42] In 1821, the township of Bridgeport became independent of Stratford.[43]

In 1821, a small community of remaining Golden Hill Pauguasett Natives, along with free blacks and runaway slaves was established in the South End along Main Street known as Little Liberia, with its own churches, schools and hotels, and served as a stop in the underground railroad. Many remaining Paugusset Indians also lived there.[44]

The West India trade died down around 1840,[33] but by that time the Bridgeport Steamship Company (1824)[45] and Bridgeport Whaling Company (1833) had been incorporated[33] and the Housatonic Railroad chartered (1836).[46][47] The HRRC ran upstate along the Housatonic Valley, connecting with Massachusetts's Berkshire Railroad at the state line. Bridgeport was chartered as Connecticut's fifth city in 1836[43][48][51] in order to enable the town council to secure funding (ultimately $150,000) to provide to the HRRC and ensure that it would terminate in Bridgeport.[52] The Naugatuck Railroad—connecting Bridgeport to Waterbury and Winsted along the Naugatuck River—was chartered in 1845 and began operation four years later.[53][54] The same year, the New York and New Haven Railroad began operation,[55] connecting Bridgeport to New York and the other towns along the north shore of the Long Island Sound. Now a major junction, the city began to industrialize.

The city's first immigrants were Irish Catholics who settled in the Sterling Hill section of the Hollow. Having come to the US to escape the famine, they arrived in town during the 1830s to build the railroad. They mostly lived in wooden four to six family tenements, often subdivided homes.

In 1842, showman P.T. Barnum spent a night in Bridgeport, and there met Charles Stratton, a local dwarf. He soon became part of Barnum's act and a star under the name "General Tom Thumb". Barnum moved to Bridgeport and built four houses in the city over the course of his life, the first being Iranistan.[56]

In 1852, Barnum began an endeavor with William Noble to develop the land (inherited by Noble) on the other side of the Pequonnock River, across the river from Bridgeport to be known as "East Bridgeport" with Washington Park at the center.[57] The new neighborhood had homes, commerce, and factories, centered around East Main Street. The neighborhood eventually became the East Side of Bridgeport (occasionally spelled "Eastside").

In 1863, during the Civil War, the Bridgeport Standard ran a series of articles encouraging the creation of a public park in the city. This led wealthy residents P.T. Barnum, William Noble and Nathaniel Wheeler to purchase the land on Long Island Sound and donating the land to the city in 1864. The land on the shore became Seaside Park. A second park was built near East Main Street, when in 1878, James Beardsley donated more than 100 acres (40 ha) to the city along the Pequonnock River under the condition that the land be "kept the same forever as a public park". Both parks were designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, known for creating Central Park. These two large public parks gave Bridgeport the nickname "The Park City".[58]

The county's Catholic seat, St. Augustine Cathedral was finished in 1869, built by the Irish who had arrived 30 year earlier. Saint James Church, predating the Archdiocese of Hartford, was the first Catholic congregation in Fairfield County, starting with 250 members in 1842. The congregation gave rise to St Augustine's in Sterling Hill, the seat of the Diocese of Bridgeport.[59]

Following the Civil War, the town held several iron foundries and factories manufacturing firearms, metallic cartridges, horse harnesses, locks, and blinds.[43] Wheeler & Wilson's sewing machines were exported throughout the world. Bridgeport absorbed the West End and the village of Black Rock and its busy harbor in 1870.[60] In 1875, P. T. Barnum was elected mayor of the town, which afterwards served as the winter headquarters of Barnum and Bailey's Circus and Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show.[9] Barnum also helped establish Fairfield County's first hospital (Conn.'s 3rd) and the Bridgeport-Port Jefferson ferry, connecting the town to Long Island.[61]

Harvey Hubbell founded Hubbell Incorporated in Bridgeport in 1888. The Holmes & Edwards Silver Co. was founded in 1882, its wares sold nationally, and the company became part of the International Silver Company in 1898.[62] (The H&E brand continued well into the 1950s and was advertised in national magazines such as LIFE and Ladies' Home Journal.)[63] Hungarian immigrants began to arrive, which led to the Ráckόczi Hungarian Aid Association in Bridgeport in 1887 and the American Hungarian Immigrant Aid Society in 1892.[64] They established themselves in the West End. In 1894, Bridgeport's Slavic immigrants played a major role in the development of the Orthodox Christian faith in America when they met with Fr Alexis Toth (now Saint Alexis) and founded Holy Ghost Russian Orthodox Church in the city's Eastside. This parish became the mother church of all Orthodox Churches in New England.

20th century

editFrom 1870 to 1910, Bridgeport became the largest industrial center in Connecticut; its population rose from around 25,000 to over 100,000, including thousands of Irish, Slovaks, Hungarians, Germans, English, and Italian immigrants. Jewish migration to the city began in the 1881, with an influx of Polish, Russian, and especially Hungarian Jews calling Bridgeport home. Bridgeport Jew Edwin Land grew up to invent the Polaroid.[65]

In 1905, Bridgeport was already "the largest industrial center in the state, $49,381,348 was invested in manufacturing and the products being valued at $44,586,519." The city was a port of entry with its imports being valued at around $656,271 in 1908.[9]

The Singer factory joined Wheeler & Wilson in producing sewing machines[9] and the Locomobile Company of America was a prominent early automobile manufacturer, producing a prototype of the Stanley Steamer and various luxury cars.[66]

The town was also the center of America's corset production, responsible for 19.9% of the national total,[9] and became the headquarters of Remington Arms following its 1912 merger with the Union Metallic Cartridge Co. Around the time of the First World War, Bridgeport was also producing steam-fitting and heating apparatuses, brass goods, phonographs, typewriters,[9] milling machines, brassieres, and saddles.[67]

Brideport's Italian immigrants settled in the "Central End", today's Little Italy, and the city was the 3rd most Italian in the state by 1910. Their newspapers were the weekly La Tribuna de Connecticut (1906–1908) and later La Sentinella (1920–1948)[68][69] The West End along Wordin Avenue, known as "Hunktown", grew into one of the largest Hungarian communities in the US.[64] It was visited by Hungarian republicans trying to take down the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, in order to garner support. The West Side nearby was home to Slovenians, French-Canadians and Swedish immigrants. By 1910 Bridgeport had grown into second largest city in Connecticut at 102,052, behind New Haven.[70][9]

Between 1910 and 1920, during World War I, the city's population exploded from 102,054 to 143,555, due to the city's role in the First World War.[71] Bridgeport had the largest factory in the world at the time, the new Remington Arms plant on Boston Avenue (on the East Side). Built in 1915, it had 13 separate buildings, each of them 5 stories, connected by a long corridor half a mile long. The purpose of the building was to fulfil a company order from the Russian tzar for a million rifles and 100 million rounds of ammunition. The construction site was protected by the National Guard to prevent Bolshevik arson. The factory by 1916 employed 16,000 people and led to the construction of "Remington City" in the Mill Hill neighborhood, and "Remington Village" in the East End, by Remington Arms.[71]

In the summer of 1915, a series of strikes imposed the eight-hour day on the town's factories; rather than moving business elsewhere, the success spread the eight-hour day throughout the Northeast.[72] Due to housing shortages in many US cities during World War I, the federal government created the US Housing Corporation. This resulted in 7 USHC housing developments being built in Bridgeport, notably Seaside Village in the South End and Black Rock Gardens in Black Rock. By this point, Remington Arms was producing 50% of America's cartridges during the war, with 17,000 employees, and homes for new workers were needed. The factory became a General Electric plant after the war.[73] The First World War had continued the city's expansion so that, on the eve of the Great Depression, there were more than 500 factories in Bridgeport, including Columbia Records' primary pressing plant and a Singer Sewing Machine factory.[74]

The 1920s saw the city's population stabilize at 143,555 after the war.[75] The Roaring Twenties brought more leisure and entertainment. In 1919, the city of Bridgeport bought Pleaseure Beach (also known as Steepchase Island) for $220,000. Pleasure Beach was an amusement park and beach on an island in the East End next to Stratford.[76] In 1920, the city parks commissioner began the process of creating a zoo in Beardsley Park.[77] Bridgeport a stop became for performances with around 20 theatres. 1922 was the year the elegantly designed Majestic and Poli Palace theatres, were built downtown, along with the Savoy Hotel. The Poli Palace theatre (built by Sylvester Poli) was the largest theatre in the state of Connecticut, with gilded hand-carved moldings and vaulted ceilings.[78] [79] The Ritz Ballroom was opened in 1923. In 1928, the city bought an 800-acre (320 ha) racetrack and landing field in Lordship to construct Bridgeport Airport.[80] Spanish immigration in 1920 and 1921 brought hundreds of migrants from Spain, particularly from Pedreguer, Valencia, where "practically the entire town migrated" to Bridgeport.[81]

During the Great Depression the city elected Socialist party candidate Jasper McLevy as mayor in 1933. McLevy's election made headlines as a New England city had a socialist mayor. Known for cutting costs, he would serve as mayor for 12 terms, finally losing in 1957.[82]

The Great Migration led southern African-Americans to Bridgeport around the 1930s (thanks to railroads)[83] along with black foreigners (such as Cape Verdean),[83] By 1930, Bridgeport had the third largest percentage of African Americans in New England. The Italian population by 1930 had more than doubled, now the city's largest ethnic group.[69] The build-up to World War II helped the city's recovery in the late 1930s.

Suburban development made its expansion into the undeveloped North End neighborhood.[84] On Park Avenue in 1962 the Museam of Art, Science and Industry (MASI) was opened to the public, today's Discovery Museam and Planetarium. Known for the newly developed approach of hands on-exhibits, the Museam became science oriented later on.[18] Continued development of new suburban housing outside of Bridgeport in the city's adjacent suburbs such as Fairfield and Milford[85] attracted middle and upper-class residents, leaving the city with a higher proportion of poor. By the 1960s, Puerto Ricans had begun to immigrate to settle to Bridgeport in large numbers, and by about 1970 had made up 10% of the city's population, or 15,000 people, the largest Puerto Rican population in Connecticut, and they would continue to grow.[86] Groups such as the local Young Lords branch organized themselves on East Main Street, leading to activism to advance the Puerto Rican community with increased access to health care, better housing, food and an end to poverty and police brutality.

As cities across the country were renovating their central business district after the war, Bridgeport attempted its own urban renewal projects in its old downtown in the early 1960s during the construction of the highways. Hunktown, with a population of 15,000 and the Irish neighborhood in the South End were demolished and replaced with highways and an industrial park. The Trumbull Shopping Park was built just outside Bridgeport city limits in Trumbull in 1965, Connecticut's first fully enclosed shopping mall.[87][88] Bridgeport under Mayor Tedesco went under the 52-acre (21 ha) State Street redevelopment project,[89] demolishing 52 acres of State Street, clearing the land for development. Replaced with modern high-rise office buildings, parking, the Route 8/25 expressway towards Waterbury and Newtown, and a shopping mall at its core.[90] Large parts of Main Street were demolished in what was called the Congress Street Renewal project, nothing was built on the land. Constructed with federal funding, on Lafayette Boulevard and Broad Street, the 450,000 acre, 2 story (with basement) Lafayette Shopping Plaza was erected, a downtown shopping mall with a Sears and a Gimbels department store as anchors connected to it. Military contracts during the 1950s and 1960s enabled the Bridgeport-Lycoming division of AVCO, founded 1951, to employ at times more than 12,000 people, building tanks, helicopters, and other military hardware. Decreased demand led to layoffs, and then closure in 1984.[91] Other examples of urban development include two city landmarks, the 12-story 855 Main Street (People's Savings Bank building), and 18-floor Park City Plaza, (State National Bank building) built 1972. The plan for three identical towers never materialized, due to the Oil Crisis and corporate vacancies.

Bridgeport was largely bypassed by the New York City companies fleeing Manhattan for suburban Fairfield County locations for various reasons; the city developed a reputation for having an industrial character thanks to the factories located right along both sides of Interstate 95, and the city's lack of urban amities and its reputation as a "blue collar" city simply wasn't the image these companies wanted to identify with in order to attract top executives, Bridgeport was being farther from New York City than Stamford or White Plains with no immediate benefits, and the trend of establishing headquarters outside of major cities in suburban campuses all played a factor.[92] As such, most skyscraper construction models for downtown Bridgeport from the 70s were never built, unlike Hartford (a city already home to major insurance companies) or Stamford. Much of north downtown Bridgeport would end up abandoned, neglected and boarded up as department and discount stores closed, leaving only federal and municipal buildings along now empty lots.[93][94]

Restructuring of heavy industry starting after the mid-20th century caused the loss of thousands of jobs and residents. Like other urban centers in Connecticut, Bridgeport suffered during the deindustrialization of the United States in the 1970s and 1980s.[95] Pleasure Beach was sold 5 years after a rollercoaster caught fire. A year later the park closed for good.[96] The old Bridgeport station caught fire in 1978.

In September 1978, Bridgeport teachers went on a 19-day strike due to deadlocked contract negotiations. A court order, as well as a state law that made strikes by public workers illegal in Connecticut, resulted in 274 teachers being arrested and jailed.[97] In November 1978, a wave of arson passed through the city's East side, with the fire chief calling it as a microcosm of "the Bronx".[98] The city suffered from overall mismanagement, for which several city officials were convicted, contributing to the economic and social decline.[99] The once busy Lafayette Shopping Plaza began to lose customers after Gimbel's closed in 1984. Replaced with a Read's store, the mall was later bought by Hi-Ho Industries and renamed "Hi-Ho Mall", until it closed in 1993 and became Housatonic Community College in 1997.[100]

Bridgeport remained the state's second city and as Hartford's population continued to shrink, Bridgeport became the largest city in Connecticut in 1974, with a population of 142,546.A 1981 Times article read; "Bridgeport... for years has suffered an image problem when compared with Hartford because of that city's role as state capital and as the site of a number of large corporations." Mayor Mandanici's response was "Hartford reported state sales taxes of $712.7 million, but Bridgeport yielded state sales taxes of $890.4 million. That's economic power, right?"[101] In 1985, Bridgeport was still Connecticut's chief manufacturing center, its major industries including General Electric, Remington Shaver, Bryant Electric, and Raybestos plants. A New York Times in 1985 stated Bridgeport was the fifth largest banking center in New England, with five of the banks based Bridgeport having assets of more than $6 billion.[16] The largest scissors, shear and surgical materials manufacturer in the world by 1946, Bridgeport-based ACME Shear closed its Bridgeport plant in 1996 due to mergers and acquisitions. The industrial operations relocated to Fremont, North Carolina. Between 1984 and 1989 the construction of the new $75 million headquarters for People's United Bank, the second largest bank in New England. The 10-story Connecticut National Bank building was demolished and replaced with the new 18-story Bridgeport Center overlooking McLevy Square, and was designed by famous architect Richard Meier and was meant to give the city a new icon[16]

Bridgeport in 1989 had more homicides per capita than any Northeastern US city over 100,000 people. Bridgeport had a smaller police force than smaller cities like Hartford or New Haven, yet hiring due to city financial issues, having not recovered from the exodus of manufacturing companies, would result in even higher taxes for residents.[102][91] The city in 1995 saw a serious reduction in violent crime, notably in its East Side, where crime rate fell by nearly half, homicides dropped, burglaries by 3/4s and stolen car thefts by more than half, among other stats, as the Phoenix Project led to barricading city streets, confusing out of town drug buyers, and preventing sellers to escape.[103]

In 1991, the city filed for bankruptcy protection but was declared solvent by a federal court.[104] Later that same year, Mayor Mary C. Moran lost the election to Joseph Ganim, at 33 years old, the youngest person to hold that office.[105] and under him the city was able to begin redevelopment with the construction of the Arena at Harbor Yard and the Ballpark at Harbor Yard.

Bridgeport made numerous efforts at revitalization. In a proposal in 1995, Las Vegas developer Steve Wynn was to build a large casino, but that project failed due to traffic concerns.[106] The project was opposed as rival Donald Trump feared a Bridgeport casino would harm his Atlantic City properties and proposed to build a theme park and potential casino on the same site.[106]

New waves of migrants from places such as Brazil, Jamaica, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Mexico, and other nations arrived in Bridgeport. Immigrants from Brazil, after the nation's inflation crisis, established themselves in the city due to the large Portuguese population already present, easing the language barrier. Bridgeport was a common second US destination for Vietnamese refugees "There's already an established community here, so that's why they come," from the New York Times in 1996. Along with them, Thai, Koreans, Chinese, and especially Laotians and Cambodians established themselves in the city. Laotians refugees settled in the West End opening businesses [107][108] Bridgeport's Mexican population grew gradually, from 24 people counted in 1970,[109] 599 people in 1990, to 2,687 by the 2000 census, becoming at that point the second largest Latino group in the city behind the city's Puerto Ricans (31,117 people), surpassing the Cuban population. Likewise, the population from other Central and South American nations continued to increase[110] while the Cuban population continued to decrease.[110][111] "There has been a big shift in ethnic groups. Just look at the restaurants that have opened in the last few years—Mexican, Brazilian, Chilean and Jamaican." an interviewee, local chamber of council president Paul Timpanelli stated in 2000 according to the Connecticut Post.

In 1999, city-owned Sikorsky Memorial Airport ceased its commercial regional flight offerings.

21st century

editIn 2003, Mayor Ganim was involved in a corruption scandal after being investigated by the FBI as he received gifts from developers in exchange for being allowed to build in Bridgeport. He was sentenced to federal prison, and was replaced by John Fabrizi.

In the early 21st century, Bridgeport has taken steps toward redevelopment of its downtown and other neighborhoods. In 2004, artists' lofts were developed in the former Read's Department Store on Broad Street. Several other rental conversions have been completed, including the 117-unit Citytrust bank building on Main Street. The recession halted, at least temporarily, two major mixed-use projects including a $1-billion waterfront development at Steel Point, but other redevelopment projects have proceeded, such as the condominium conversion project in Bijou Square.[112] In 2009, the City Council under Mayor Finch approved a new master plan for development, designed both to promote redevelopment in selected areas and to protect existing residential neighborhoods.[113] The plan was updated in April 2019.[114] In 2010, the Bridgeport Housing Authority and a local health center announced plans to build a $20 million medical and housing complex at Albion Street, making use of federal stimulus funds and designed to replace some of the housing lost with the demolition of Father Panik Village.[115]

The Steel Point (or Steelpointe) project of Bridgeport's on the lower portion of the East Side finally led to the construction of a big box retailer in 2013, along with other stores, shops, and a lighthouse with a marina and oyster bar). The plan for high-end mixed use apartments is in place, although concerns about gentrification have been raised. A hotel is also in the works.[116] A new proposed train station in East Bridgeport, meant to be completed in 2021, was postponed in 2019.

By 2013 the city and local business owners agreed that work needed to be done in the downtown area north of Fairfield Avenue, nicknamed Downtown North, above. Made up of old empty brick buildings which were neglected for years, the city and developers began their rehabilitation starting in 2015, most of which are now converted apartments or retail.[93][117] Bridgeport's downtown renovation has resulted in various restaurants, the renovation of the Bishop Arcade Mall, a comedy club, and theatres. A 2022 plan to renovate McLevy Hall is in place.[118]

In 2017, MGM had announced plans to build a waterfront casino and shopping center in the city, awaiting approval by the state government. If built, the development would have created 2,000 permanent jobs and about 5,779 temporary jobs.[119] After a legal battle with the Mohegan and Pequot tribes on the right to build a casino in Connecticut, the project "appears to be dead", and tenants such as Bridgeport Boatworks now occupy the proposed space.[120] The construction of Honey Locust Square began on the East End, which when complete will house a supermarket (something the neighborhood lacks), a public library, a health center, and a retail building.[121]

Notable speeches

editOn March 10, 1860, Abraham Lincoln spoke in the city's Washington Hall, an auditorium at the old Bridgeport City Hall (now McLevy Hall), at the corner of State and Broad Streets. The largest room in the city was packed, and a crowd formed outside, as well. Lincoln received a standing ovation before taking the 9:07 pm train that night back to Manhattan.[122][123] A plaque marks the site where Lincoln spoke; later that year, he was elected president.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke three times at the Klein Auditorium during the 1960s, as well as at the University of Bridgeport and the original Central High School (today Bridgeport City Hall)., as well as in Bridgeport City Hall. Additionally, President George W. Bush spoke before a small group of Connecticut business people and officials at the Playhouse on the Green in 2006.[124] President Barack Obama also spoke at the Harbor Yard arena in 2010 to gain support for the campaign of Democratic Governor Dan Malloy.[125]

Timeline of notable first and inventions

edit- 1896 – The chain socket was invented in Bridgeport

- 1904 – The AC plug outlet was also invented in Bridgeport by Harvey Hubbell

- 1877 – The world's first telephone exchange was established in Bridgeport by the District Telephone Company.[126] The first commercial phone exchange was opened in nearby New Haven two years later.[10]

- 1903 – German immigrant Gustave Whitehead claimed to have flown the first airplane in Bridgeport two years before the Wright Brothers, confirmed in the Bridgeport Post.[127]

- 1914 – Caresse Crosby, the woman credited with inventing the modern bra, sold her patent to Bridgeport-based Warnaco which mass-produced it for the first time. The alphabet bra sizing system was invented, which we still use today, in 1937 by the Bridgeport company.[128]

- 1949 – The first dental school was founded in the University of Bridgeport[129]

- 1920 – The Frisbie Pie Company was founded in Bridgeport in 1871.[clarification needed][126]

- 1949 – The first daily UHF television station, KC2XAK aired in Bridgeport. It was a test conducted by NBC and was known as "Operation Bridgeport".[126]

- 1965 – The first Subway restaurant was founded in Bridgeport. Student Fred DeLuca needed money to attend college, and with the help of Peter Buck started "Pete's Subs". Renamed Subway, the franchise grew into one of the largest fast food chains in the world.[130]

- 1981 – The first telephone banking service in the United States was provided by People's Bank to its clients.

Geography

editBridgeport lies along Long Island Sound at the mouth of the Pequonnock River.

Neighborhoods

editBridgeport has many distinct neighborhoods,[131] divided into five geographic areas: Downtown, the East Side, the North End, the South End, and the West Side.[132]

- Downtown

- The Hollow

- The Hollow

- Enterprise Zone

- East Side

- Steel Point

- Lower East Side/East Side

- Upper East Side/ North Bridgeport

East End

- Boston Avenue/Mill Hill

- East End

- Newfield

- Pleasure Beach

- North End

- Lake Forest

- Lake Success

- Reservoir/Whiskey Hill

- Old Town Road

- Brooklawn/St. Vincent

- Central End/Little Italy

- Brooklawn

- South End

- Seaside Park

- Soundgate

- West Side

- Black Rock

- West Side

- West End

- Black Rock

- St. Mary's by the Sea

Climate

editUnder the Köppen climate classification, Bridgeport straddles the humid subtropical climate (Cfa) and humid continental climate (Dfa) zones with long, hot summers, and cool to cold winters, with precipitation spread fairly evenly throughout the year. Bridgeport, like the rest of coastal Connecticut, lies in the broad transition zone between the colder continental climates of the northern United States and southern Canada to the north, and the warmer temperate and subtropical climates of the middle and south Atlantic states to the south.

The warm/hot season in Bridgeport is from mid-April through early November. Late day thundershowers are common in the hottest months (June, July, August, September), despite the mostly sunny skies. The cool/cold season is from late November though mid March. Winter weather is far more variable than summer weather along the Connecticut coast, ranging from sunny days with higher temperatures to cold and blustery conditions with occasional snow. Like much of the Connecticut coast and nearby Long Island, NY, most of the winter precipitation is rain or a mix and rain and wet snow in Bridgeport. Bridgeport averages about 29 inches (75 cm) of snow annually, compared to inland areas like Hartford and Albany which average 45–60 inches (110–150 cm) of snow annually.

Although infrequent, tropical cyclones (hurricanes/tropical storms) have struck Connecticut and the Bridgeport metropolitan area. Hurricane landfalls have occurred along the Connecticut coast in 1903, 1938, 1944, 1954 (Carol), 1960 (Donna), Hurricane Gloria in 1985, and Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Bridgeport lies in USDA garden hardiness zone 7a, averaging about 92 days annually with freeze. The coastal location of Bridgeport allows it to be milder than locations well south but inland. For example, the record coldest low temperature at Atlanta is -8 F, while the record coldest at Bridgeport is -7 F. Coastal Connecticut is the broad transition zone where so-called "subtropical indicator" plants such as cold hardy palms and other broadleaf evergreens can successfully be cultivated. As such, Southern Magnolias, Needle Palms, Windmill palm, Loblolly Pines, and Crape Myrtles are grown in private and public gardens. Like much of coastal Connecticut, Long Island, NY, and coastal New Jersey, the growing season is rather long in Bridgeport—averaging 210 days from April 8 to November 5 according to the National Weather Service in Bridgeport.

The average monthly temperature ranges from 31.4 °F (−0.3 °C) in January to 75.7 °F (24.3 °C) in July. The record low is −7 °F (−22 °C), set on January 22, 1984, while the record high is 103 °F (39 °C), set on July 22 in 1957 and 2011.[133]

Precipitation averages 44.9 inches (1,140 mm) annually, and is somewhat evenly distributed throughout the year, with March and April the wettest months. Annual snowfall averages 33.6 inches (85 cm), falling almost entirely from December to March. As is typical of coastal Connecticut, snow cover does not usually last long, with an average of 33 days per winter with snow cover of at least 1 inch (2.5 cm).

| Climate data for Bridgeport, Connecticut (Sikorsky Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1948–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

68 (20) |

84 (29) |

91 (33) |

97 (36) |

97 (36) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

99 (37) |

89 (32) |

81 (27) |

76 (24) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.7 (13.7) |

55.3 (12.9) |

64.8 (18.2) |

76.4 (24.7) |

85.1 (29.5) |

90.7 (32.6) |

93.8 (34.3) |

91.5 (33.1) |

86.2 (30.1) |

78.1 (25.6) |

67.9 (19.9) |

59.7 (15.4) |

95.4 (35.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 38.4 (3.6) |

40.5 (4.7) |

47.4 (8.6) |

58.3 (14.6) |

68.4 (20.2) |

77.7 (25.4) |

83.4 (28.6) |

81.9 (27.7) |

75.4 (24.1) |

64.4 (18.0) |

53.6 (12.0) |

43.8 (6.6) |

61.1 (16.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.4 (−0.3) |

33.1 (0.6) |

39.3 (4.1) |

50.0 (10.0) |

60.0 (15.6) |

69.6 (20.9) |

75.7 (24.3) |

74.5 (23.6) |

67.6 (19.8) |

56.4 (13.6) |

46.0 (7.8) |

37.0 (2.8) |

53.4 (11.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 24.4 (−4.2) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

32.3 (0.2) |

41.7 (5.4) |

51.7 (10.9) |

61.5 (16.4) |

67.9 (19.9) |

67.0 (19.4) |

59.8 (15.4) |

48.3 (9.1) |

38.4 (3.6) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

45.7 (7.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 6.6 (−14.1) |

9.9 (−12.3) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

40.8 (4.9) |

49.8 (9.9) |

59.1 (15.1) |

56.9 (13.8) |

46.2 (7.9) |

34.2 (1.2) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

15.6 (−9.1) |

4.6 (−15.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

−6 (−21) |

4 (−16) |

18 (−8) |

31 (−1) |

41 (5) |

49 (9) |

44 (7) |

36 (2) |

26 (−3) |

13 (−11) |

−4 (−20) |

−7 (−22) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.18 (81) |

3.12 (79) |

4.09 (104) |

4.16 (106) |

3.58 (91) |

3.77 (96) |

3.32 (84) |

3.98 (101) |

3.96 (101) |

3.84 (98) |

3.11 (79) |

3.98 (101) |

44.09 (1,120) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.5 (22) |

10.7 (27) |

7.0 (18) |

0.9 (2.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.9 (2.3) |

5.5 (14) |

33.6 (85) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.2 | 10.4 | 11.2 | 11.4 | 12.1 | 11.2 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 9.9 | 9.4 | 11.5 | 124.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.5 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 14.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.1 | 65.8 | 65.9 | 63.9 | 70.2 | 73.6 | 73.0 | 73.9 | 74.1 | 70.3 | 70.2 | 69.6 | 69.7 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 18.0 (−7.8) |

18.7 (−7.4) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

34.3 (1.3) |

46.8 (8.2) |

57.4 (14.1) |

63.1 (17.3) |

63.5 (17.5) |

57.2 (14.0) |

45.9 (7.7) |

36.0 (2.2) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

41.0 (5.0) |

| Source: NOAA[133][134][135] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 1,089 | — | |

| 1820 | 1,500 | 37.7% | |

| 1830 | 2,800 | 86.7% | |

| 1840 | 3,294 | 17.6% | |

| 1850 | 7,560 | 129.5% | |

| 1860 | 13,299 | 75.9% | |

| 1870 | 18,969 | 42.6% | |

| 1880 | 27,643 | 45.7% | |

| 1890 | 48,866 | 76.8% | |

| 1900 | 70,996 | 45.3% | |

| 1910 | 102,054 | 43.7% | |

| 1920 | 143,555 | 40.7% | |

| 1930 | 146,716 | 2.2% | |

| 1940 | 147,121 | 0.3% | |

| 1950 | 158,709 | 7.9% | |

| 1960 | 156,748 | −1.2% | |

| 1970 | 156,542 | −0.1% | |

| 1980 | 142,546 | −8.9% | |

| 1990 | 141,686 | −0.6% | |

| 2000 | 139,529 | −1.5% | |

| 2010 | 144,229 | 3.4% | |

| 2020 | 148,654 | 3.1% | |

| Population 1840–1970[75] U.S. Decennial Census[136] 2018 Estimate[137] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[138] | Pop 2010[139] | Pop 2020[140] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 43,158 | 32,794 | 24,404 | 30.93% | 22.74% | 16.42% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 40,974 | 46,472 | 48,690 | 29.37% | 32.22% | 32.75% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 352 | 286 | 228 | 0.25% | 0.20% | 0.15% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 4,459 | 4,781 | 4,024 | 3.20% | 3.31% | 2.71% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 102 | 66 | 31 | 0.07% | 0.05% | 0.02% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 1,218 | 1,930 | 2,938 | 0.87% | 1.34% | 1.98% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 4,788 | 2,800 | 5,486 | 3.43% | 1.94% | 3.69% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 44,478 | 55,100 | 62,853 | 31.88% | 38.20% | 42.28% |

| Total | 139,529 | 144,229 | 148,654 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

editAs of the 2010 census, there were 144,229 people living in the city. The racial makeup of the city residents was 39.6% White; 34.6% Black or African American; 3.4% Asian; and 4.3% from two or more races. A total of 38.2% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 50,307 households, out of which 34.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.0% were married couples living together, 24.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.9% were non-families. 29.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.70 and the average family size was 3.34.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 28.4% under the age of 18, 11.2% from 18 to 24, 30.5% from 25 to 44, 18.4% from 45 to 64, and 11.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $34,658, and the median income for a family was $39,571. Males had a median income of $32,430 versus $26,966 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,306. About 16.2% of families and 18.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.8% of those under age 18 and 13.2% of those age 65 or over.

According to the 2020 five-year community survey, 48.2% of Bridgeport's population speaks a different primary language at home other than English, 33.8% percent of the city's total population speaks Spanish at home, and 22.5% speak English less than very well.[141] Bridgeport has the largest percentage and population of Hispanic Americans in the state of Connecticut. The city is known for having one of the largest communities of Puerto Ricans in the United States; Bridgeport has the 7th largest Puerto Rican population in the United States, with 30,250 people claiming Puerto Rican heritage in 1990, that number has grown to about 31,900 (22.10% of the population) in 2013.[142][143] 45,270 people (31%)[144] of Bridgeport's population is foreign born in 2010. Other than Puerto Ricans, 5.4% of Bridgeport's population was noted under Mexican in 2013,[145] a number that has grown to 5.8% (8,479 people) in the 2020 five-year American Community Survey, meaning Bridgeport has the largest Mexican population in New England.[146]Dominicans are 5,248 (3.53%) of Bridgeport's population. The total Latino Central American population (Guatemalans, Salvadorians, Nicaraguans, Hondurans, Costa Ricans, Panamanians) is 6,701 people total in the city (4.507%). 8,454 South Americans (5.697%); 4,020 Equadorians, 2,326 Colombians, Peruvians, and then populations from every Latin American nation except Bolivia can be found, with the smallest group being Paraguayans at 16 people according to the census.[147][148] [149] Bridgeport also has the largest Cuban population in the state, with more than 1,000 of the state's 10,600 Cubans living in Bridgeport, although down from the at least 5,000 Cubans in Bridgeport in 1980, and even more before that time in the 1950s according to the CTPost. Bridgeport was once a major destination for migrating Cubans, but many families have since moved to the city's suburbs or Florida. Bridgeport, along with Danbury, CT were considered as a potential locations for a new Ecuadorian consulate, but it instead opened in New Haven, CT, due to its immigrant welcoming mayor, in 2008.[150]

As for Portuguese-speaking peoples, the city also has the 12th largest Cape Verdean population in the country.[83] The group settled in the Hollow to work in factories and established a social club in the 1940s. The Cape Verdean Association of Bridgeport is located in the Hollow today.[151] The Portuguese community in the city is the largest in the state and the population primarily hails from the Tras Os Montes region of Portugal according to a 2018 research study, and the Hollow is considered the "Portuguese section" of Bridgeport.[152] The large Brazilian population in Bridgeport and Danbury led to the opening of a Brazilian consulate in the state capital of Hartford.[153] Migration to Connecticut began in the 90s, social networks brought immigrants from Governador Valadares, Minas Gerais in Brazil to Bridgeport, CT and Framingham, MA.[154] Fairfield County has the 7th largest Brazilian population of the United States, and 1/3rd of them live within Bridgeport's city limits, most of whom reside in the city's North End and St. Vincent neighborhood.

A small population of people from various majority-Muslim nations exists along with Kurds, at least 4,000 according to an estimate by a local mosque in 2008. Bridgeport Public Schools now observes Eid al-Fitr, effective 2024, thanks to a campaign by city 8th graders from Park City Magnet School, which found 10% of the school body was Muslim in a school project. Bengali in 2022 was the fifth most common primary language for Bridgeport Public School students (behind English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Haitian Creole, and is followed by Arabic at sixth place).[155][156] There is also a sizeable Kurdish population in Bridgeport, primarily from Iraq.[157] In total (and counting East and Southeast Asians), Bridgeport had 7,725 Asian residents according to the 2021[158] 5 year American Community Survey, up from 2020's count, 5,553 Asians. The largest national origin groups and their estimated populations are Vietnamese (1,258 people), Indian (1,153 people), Chinese, excluding Taiwanese and Pakistanis (both 982 people), and Filipinos (729 people). Other groups with over 500 people include Laotians and Cambodians, Bangladeshi Americans in the city numbered 385 people in the survey.[159]

Jamaicans, the state's largest foreign-born group,[160] have a significant presence in Bridgeport, with 6.3% of Bridgeport's population being Jamaican in 2013.[161] Bridgeport in 2013 was 10.2% non-Hispanic West Indian.[162]

At least 92 languages are spoken as primary languages by Bridgeport Public School students according to district data in 2022. 3,145 students are missing data in primary language.[163]

The Bridgeport-Stamford metropolitan area (i.e.: Fairfield County) is home to the 7th largest percentage of Italian ancestry in the country (the population is 16.5% Italian). Italian Americans until 1985 were the largest ethnic group in Bridgeport itself, and had been since the 1920s.[164][165] According to 2010 census data, the Bridgeport MSA, containing all of Fairfield County, is the most economically unequal region in America, with 57% of the wealth going to the top income quintile.[166][167]

As of the census of 2000, there were 139,529 people, 50,307 households, and 32,749 families living in the city. The population density was 8,720.9 inhabitants per square mile (3,367.2/km2). There were 54,367 housing units at an average density of 3,398.1 per square mile (1,312.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 45.0% White, 30.8% African American, 0.5% Native American, 3.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 31.9% of the population.[168] European (white) ancestry groups include: Italian (8.6%), Irish (5.1%), Portuguese (2.9%), Polish (2.8%), and German (2.4%).

Economy

editSince the decline of its industrial sector beginning in the middle of the 20th century, Bridgeport has gradually adjusted to a service-based economy. As late as 1985, the city was still home to company plants such as General Electric, with 1,900 employees, and Remington Products, with 900, both of which are now closed. Bryant Electric didn't close its plant until 1988. The last major factory to close was the Sikorsky helicopter plant in 2015.[169] Various famous industrial companies, that were founded and based in Bridgeport, such as ACME Sheer, Fortune 1000 Hubbell Incorporated, etc. are now based in suburban Shelton, two towns away. Subway, which started out in Bridgeport in 1965, is now based in Milford.

Though a level of industrial activity continues, healthcare, finance, and education have become the centerpieces of Bridgeport's economy.

The two largest employers in the city are Bridgeport's primary hospitals, Bridgeport Hospital and St. Vincent's Medical Center. Park City Hospital in the South End closed in 1993 and was reopened in 2010 as elderly and homeless housing units.[170]

In April 2022, M&T Bank of Buffalo, New York, merged with Bridgeport-based People's United Financial. The combined company is now the 11th largest bank in the United States, and gave M&T a foothold in the New England market, in total serving 12 states. Although M&T laid off Bridgeport employees (which made national headlines),[171] the company as part of this effort made Bridgeport Center the regional M&T headquarters of New England.[172]

Top employers

editTop employers in Bridgeport according to the city's 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report:[173]

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bridgeport Hospital | 3,243 |

| 2 | St. Vincent's Medical Center | 1,800 |

| 3 | M&T Bank | 1,117 |

| 4 | Jewish Senior Services Center | 358 |

| 5 | Goodwin University | 526 |

| 6 | Sikorsky Aircraft | 383 |

| 7 | Housatonic Community College | 343 |

| 8 | Lacey Manufacturing Co. | 350 |

| 9 | Bridgeport Healthcare Center | 297 |

| 10 | alphabroder Prime Line | 253 |

Arts and culture

editPerforming arts

editTheater and music

editVenues for live theater and music events include:[174]

- Downtown Cabaret Theatre – cabaret, children's theater, concerts

- The Stress Factory (300 seats) – comedy club with national and local acts

- Klein Memorial Auditorium (1,400 seats) – home to the Greater Bridgeport Symphony, touring shows and concerts

- Total Mortgage Arena – sporting events venue, but also hosts large concerts

- Hartford HealthCare Amphitheater - outdoor concert venue

Music festivals and concert series

editBridgeport was the annual home to Gathering of the Vibes, a weekend-long arts, music and camping festival, until it ended in 2015.[175]

Beginning in 2022, Bridgeport played host to the Sound on Sound Music Festival, at Seaside Park. Past performers included; John Mayer, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Dave Matthews Band, Hozier, and The Roots.[176]

The Greater Bridgeport Symphony, established in 1945, performs at Bridgeport's 1,400-seat Klein Memorial Auditorium. Gustav Meier directed the orchestra from 1972 to 2013.

Museums and zoos

edit- The Discovery Science Center and Planetarium emphasizes exhibits on science, with the state's only Challenger Center, affiliated with the national space program. Opened in 1962 and run by SHU as of 2020.[177]

- The Housatonic Museum of Art at Housatonic Community College has the largest collection of art of any two-year college in the nation. Founded in 1967 by collage art director Bob Chernow. Shows both western and non-western art from different eras, including sculptures.[178]

- The Barnum Museum celebrates the showman, circuses and Bridgeport history. Currently under renovation, a room is open to visitors every Thursday.

- The Beardsley Zoo, opened 1922, is the only such center in Connecticut,[clarification needed] and is the state's largest zoo.[174][179]

The Greater Bridgeport metropolitan area is home to the Maritime Aquarium in Norwalk, 30 minutes from downtown Bridgeport.[180] One of the two aquariums in Connecticut, the aquarium focuses on Long Island Sound as well as creatures and conservation efforts from around the world.[181]

Historic districts

editBridgeport has five local historic districts, where exterior changes to structures are under the control of two Historic District Commissions:

- Black Rock Harbor Historic District

- Pembroke City Historic District

- Stratfield Historic District

- Barnum-Palliser Development Historic District

- Marina Park Historic District

- Downtown North Historic District

- Downtown South Historic District

- Remington City Historic District

- Black Rock Gardens Historic District

- Seaside Village Historic District

- AMFAB Art Building

Bridgeport was once home to a Little Asia along Wood Avenue in the West Side, established in 2012 by local business owners with a sign and a festival every year. By 2016 the name had fallen out of use, and the committee no longer exists. The more or less 3 or 4 block area is still home to Asian restaurants, an insurance and tax agency with Vietnamese, Mandarin, Laotian, Cantonese as well as Spanish language services,[182] and a Vietnamese grocery store.[183][184]

Cuisine

editNerdWallet ranked Bridgeport the 100th most foodie city in the United States, 2nd in Connecticut behind New Haven (which was ranked #97). Nerdwallet in 2022 ranked Bridgeport as the 17th most ethnically diverse city in the United States, making it the most diverse in New England, and the third most diverse in the New York Metropolitan Area in an annual ranking. It ranked 23rd in 2021, and #22 in 2015. It is #28 on Niche.com "2022 Most Diverse Cities in America" list. Bridgeport's Madison Avenue, and Hollow Brazilian restaurants, located alongside various Portuguese ones, have been mentioned by publications such as the New York Times. Examples include churascaria restaurants.[185] It is "among the top cities in the state to immerse yourself in Brazilian traditions" according to CTBites.[186] Azteca was ranked among the best Mexican restaurants in Connecticut in 2020 according to Connecticut Magazine, along with Pho Hong Thom and Pho Saigon in Bridgeport's Little Asia on the West Side for best Vietnamese places in the state.[187][188]

Sports

edit| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridgeport Islanders | AHL | Total Mortgage Arena | 2001 | 0 |

| CT United FC | MLS Next Pro | New Waterfront Stadium | 2024 | 0 |

Total Mortgage Arena serves as the city's sports and hospitality center. Seating 10,000, the Arena serves as the home rink of the Bridgeport Islanders American Hockey League team, the farm team of the New York Islanders of the National Hockey League.[189] Starting in 2024, it also serves as the home of the New York Sirens of the Professional Women's Hockey League.[190]

The arena served as the temporary home of the Westchester Knicks of the NBA G League (the farm team for the NBA New York Knicks) from 2021 to 2023 when the team's home stadium, Westchester County Center in White Plains, NY iwas being used as a vaccination clinic.[191][192]

For college teams, Total Mortgage serves as the home court of Fairfield University's basketball team.

The Ballpark at Harbor Yard served as a minor-league baseball stadium from 1998 to 2017. It was built in 1998 to serve as the homefield of the Bridgeport Bluefish. From 2001 to 2003 it was the homefield for the Bridgeport Barrage, a Major League Lacrosse team. It is downtown on a former brownfield site. It is visually prominent to commuters on I-95 or on passing trains. On August 8, 2017, Mayor Joe Ganim announced that the Bluefish would be ending their 20-year stint at the ballpark at the end of the 2017 season. The ballpark was converted into an amphitheatre. The Bluefish played their final home game at the park on September 17, 2017, losing by a score of 9–2 to the Somerset Patriots.[193]

Kennedy Stadium serves as a community sports facility. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, it was the home of an Atlantic Coast Football League minor league football team, the Bridgeport Jets, a New York Jets farm team also known locally as the Hi-Ho Jets due to their sponsorship by the (Hi-Ho) D'Addario construction company.

Fairfield University is in the neighboring town of Fairfield, and many of the athletic teams play on campus. Only the men's and women's basketball teams play in Bridgeport.

Nutmeg Curling Club, one of two curling clubs in Connecticut, is in Bridgeport. It is the home club of the 2013 USA Mixed National Champions,[194] led by club members Derek Surka and Charissa Lin. The club is a member of the Grand National Curling Club Region.

Bridgeport native Jim O'Rourke was the first baseball player to earn a hit in National League history in 1876. The founder and original owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Charles Ebbets, married his second wife in Bridgeport in 1922, five years before his death.

In early 2024, MLS Next Pro awarded an expansion team to Bridgeport.[195] Connecticut United FC plan to play at a new stadium to be located on the waterfront at a former dog-racing track, as stadium plans were approved by the Bridgeport government in November 2023.[196]

Amateur soccer team GZS Bridgeport play in the UPSL, playing home games at Kennedy Stadium.

Parks and recreation

edit-

Soldiers and Sailors Monument – Seaside Park

-

Seaside Park – Spanish American War memorial

-

The beach at Seaside Park

-

James Beardsley Monument at Beardsley Park in Bridgeport

The city has 1,300 acres of public space, with a pocket park in nearly every neighborhood.[197] Bridgeport's public park system led to its official nickname, "the Park City". The city's first public park was the westerly portion of McLevy Green, first set aside as a public square in 1806;[198] the Clinton Park Militia Grounds (1666) and Old Mill Green (1717) were set aside earlier as public commons by the towns of Fairfield and Stratford, respectively. Washington Park in 1850 was located in the center of East Bridgeport.[199] As the city rapidly grew in population, residents recognized the need for more public parks and by 1864, Barnum and other residents had donated approximately 44 acres (18 ha) to create Seaside Park, now increased by acquisition and landfill to 375 acres (152 ha).[200] In 1878, over 100 acres (40 ha) of land bordering the Pequonnock River was added as Beardsley Park.[201] Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed New York City's Central Park, designed both Seaside and Beardsley Parks.[202] Over time, more parks were added including 35-acre (14 ha) Beechwood Park and Pleasure Beach, home to an amusement park for many years. Went Field on the West End, between Wordin Avenue and Norman Street, used to be the winter headquarters of Barnum's circus.

Architecture

edit-

Bridgeport Center – An 18-floor postmodern building designed by Richard Meier and built 1989. It is the tallest building in Bridgeport.

-

Park City Plaza – an 18-story modernist style building completed in 1973. Originally the headquarters for the State National Bank, it was designed by Palestinian born architect Victor Bisharat and built by the F.D. Rich Company of Stamford.[203]

-

Hotel Beach, a 13-story Art Deco building built downtown in 1927 on Fairfield Avenue

-

Apartment house on Milne Street, in Sterling Hill, settled by the Irish. Three deckers, brick tenerments and small houses are found here.

-

Remington City rowhouses on Bond Street. Built for workers during WW1, emulates European cottage styles.

-

Queen Anne style tenements within the Barnum Palliser historic district in the South End, built by Barnum in the 1880s for working class families

-

Golden Hill United Methodist Church in between Downtown and the Hollow near City Hall

-

CityTrust Bank building, finished 1929. Today a Citi Bank branch and apartments above.

-

McLevy Hall, built 1854, 3 stories, the original Bridgeport City Hall and County Courthouse. Renamed after Mayor McLevy.

Bridgeport was largely bypassed by Fortune 500 companies moving to Fairfield County in the second half of the 20th century, due to the city's growing reputation for having a rough industrial character. Thus was also largely bypassed by the skyscraper construction boom of the 70s and 80s, resulting in fewer modern skyscrapers than otheir cities[204] The tallest building in Bridgeport is currently the Richard Meier-designed 16-story, 248-foot (76 m) Bridgeport Center, which was completed in 1989 and surpassed the 18-story Park City Plaza, which was completed in 1973.

Bridgeport in the early 20th century banned further construction of the triple decker, very common in the Hollow, Madison Avenue, in the East Side with other working class housing styles and Victorian mansions, the West Side with Queen Ann multifamily homes, parts of Black Rock, and the East End neighborhood.[205][206][107]

Government

editThe city is governed by the mayor-council system. Twenty members of the city council are elected from districts. Each district elects two members. The mayor is elected at-large by the entire city

Bridgeport is notable for having had a socialist mayor for 24 years, Jasper McLevy, who served from 1933 to 1957.

The city's current mayor, Joseph P. Ganim, is a convicted felon who was sentenced to nine years in prison after conviction in 2003 of 16 federal counts including racketeering, extortion, conspiracy, bribery, mail fraud, and filing false tax returns arising from Ganim's "role in a six-year scheme to shake down city contractors…".[207][208][209]

In June 2006, Mayor John M. Fabrizi admitted that he had used cocaine while in office.[210]

Bridgeport is recognized for its polarizing political culture. Mayor Ganim has served the city seven terms since first taking office in 1991.[208] After his release from prison in 2015, Ganim announced his mayoral campaign to serve a sixth term in office. His campaign ran on a theme of providing him with a "second-chance," as he was renowned for his work of escaping the city from bankruptcy and build its economy from a post-industrial standpoint.[211]

In a divisive primary election between him, the city's mayor at the time, Bill Finch, and University of Bridgeport professor and real estate developer, Mary-Jane Foster, Ganim was able to receive the endorsement of the politically volatile Democratic Town Committee, paving the way to his victory for being reelected mayor at the end of year.[211]

Bridgeport's Democratic Town Committee has the authority to nominate and endorse Democratic candidates running for local office, and they have the resources to outperform challenger slates that may compete with them. The chairman is former state representative and local restaurateur, Mario Testa.[212]

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of October 29, 2019[213] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Active voters | Inactive voters | Total voters | Percentage | |

| Republican | 4,505 | 205 | 4,710 | 6.06% | |

| Democratic | 48,117 | 2,154 | 50,271 | 64.73% | |

| Unaffiliated | 20,922 | 1,136 | 22,058 | 28.40% | |

| Minor parties | 589 | 32 | 621 | 0.80% | |

| Total | 74,133 | 3,527 | 77,660 | 100% | |

Bridgeport votes Democratic at the presidential level. In 1972 Richard Nixon was the last Republican to win the city; since then Democrats have prevailed, often by comfortable margins, the lone exception being 1984 when Walter Mondale carried the city by just 76 votes (0.16 percent) over Ronald Reagan.

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 79.44% 33,515 | 19.60% 8,269 | 0.96% 404 |

| 2016 | 80.98% 32,035 | 16.67% 6,596 | 2.35% 929 |

| 2012 | 85.75% 32,135 | 13.79% 5,168 | 0.46% 173 |

| 2008 | 83.52% 33,976 | 15.99% 6,507 | 4.89% 199 |

| 2004 | 70.66% 26,280 | 27.76% 10,326 | 1.57% 585 |

| 2000 | 72.68% 24,303 | 22.15% 7,406 | 5.18% 1,731 |

| 1996 | 69.16% 22,883 | 20.51% 6,785 | 10.33% 3,419 |

| 1992 | 53.20% 22,321 | 31.34% 13,149 | 15.46% 6,486 |

| 1988 | 57.50% 23,831 | 41.22% 17,084 | 1.27% 527 |

| 1984 | 49.75% 24,332 | 49.59% 24,256 | 0.66% 321 |

| 1980 | 51.24% 23,505 | 41.82% 19,185 | 6.94% 3,185 |

| 1976 | 55.37% 26,330 | 43.79% 20,824 | 0.83% 397 |

| 1972 | 43.67% 24,572 | 54.09% 30,436 | 2.25% 1,265 |

| 1968 | 53.27% 30,065 | 37.23% 21,014 | 9.50% 5,363 |

| 1964 | 69.90% 43,710 | 30.10% 18,818 | 0.00% 0 |

| 1960 | 61.14% 41,950 | 38.86% 26,667 | 0.00% 0 |

| 1956 | 38.57% 26,560 | 61.43% 42,308 | 0.00% 0 |

Taxes

editBridgeport has one of the highest property tax rates in Connecticut.[216] A 2017 Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Minnesota Center of Fiscal Excellence study determined that Bridgeport had the second-highest property tax burden of any U.S. city (after Detroit), and the fourth-highest for commercial properties valued at more than $1 million (after Detroit, New York City, and Chicago).[217]

In 2016, Bridgeport enacted a 29% increase in the property tax rate, among the highest one-year property tax rate increases in recent U.S. history, in an effort to reduce the municipal deficit.[218] A citywide reassessment in 2015 determined that the value of taxable property in the city was $6 billion, a decline of $1 billion; the property tax increases, combined with property value decreases, have been a consistent political issue in the city.[218]

Education

editHigher education

editBridgeport is home to the University of Bridgeport, Housatonic Community College, Paier College, St. Vincent's College, and the Yeshiva Gedola of Bridgeport. The Yeshiva Gedola is the home of the Bridgeport Community Kollel, a rabbinic fellowship program.[219] The University of Bridgeport's Ernest C. Trefz School of Business offers undergraduate and graduate programs.

Sacred Heart University is located in the neighboring suburb of Fairfield on the town line, with its campus extending into the North End of Bridgeport on Park Avenue. Many of its students live in the city's North End. It is the second largest Catholic University in New England (behind Boston College). [220] Sacred Heart has campuses in nearby Stamford, as well as Griswold, CT and Dingle, Ireland, as well as St. Vincent's College in Bridgeport. The University of Bridgeport has secondary campuses in Waterbury and Stamford. Paier College near the University of Bridgeport is the only Private Arts college in Connecticut. Founded in 1946 in West Haven and previously located in Hamden, the college recently relocated to Seaside Park in Bridgeport.[221][222]

The Greater Bridgeport Area (made up of the surrounding towns) is home to Fairfield University in neighboring Fairfield, and Western Connecticut State University in Danbury.

Public education

editThe city's public school system has 30 elementary schools, three comprehensive high schools, two alternative programs and an interdistrict vocational aquaculture school. The system has about 20,800 students, making the Bridgeport Public Schools the second largest school system in Connecticut after Hartford. It is ranked #158 out of the 164 Connecticut school districts.[223] The school system employs a professional staff of more than 1,700.

The city has started a large school renovation and construction program, with plans for new schools and modernization of existing buildings.

Public high schools

- Bassick High School was established in 1929. It serves students residing south of Route 1, in the Black Rock, the Hollow, Downtown, West End and South End neighborhoods. 1181 Fairfield Ave, Bridgeport, CT 06605.

- Central High School (CHS) was established in 1876. The current building was built in 1964. It houses the Central magnet program. Serves students from north of Route 1, including the North End, part of Brooklawn and St. Vincent neighborhoods. 1 Lincoln Blvd, Bridgeport, CT 06606.

- Warren Harding High School is home to the International Baccalaureate Program (IBO) and the Health Magnet Program in association with Bridgeport Hospital, St. Vincent's Medical Center, and Bridgeport Manor. It is the alma mater of Walt Kelly, creator of Pogo. It serves East End, East Side, Mill Hill and North Bridgeport students. 379 Bond St, Bridgeport, CT 06610.

- Bridgeport Regional Vocational Aquaculture School (BRVAS) is a half-day school specializing in marine and aquaculture curricula near Captain's Cove and open to students from surrounding towns. It serves all Bridgeport applicants and applicants from neighboring towns' (Trumbull, Stratford, Fairfield, Milford, Shelton, Monroe, and Region 9) school districts. 60 St. Stephens Rd, Bridgeport, CT.

Public magnet high schools

- Fairchild Wheeler Interdistrict Multi-Magnet High School is three specialIzard STEM high schools in one building: an IT and software technology school, aerospace/hydrospace school, and biotechnology school. It serves all Bridgeport applicants and applicants from neighboring towns (Trumbull, Stratford, Fairfield, Milford, Shelton, Monroe, Region 9). Acceptance is by public lottery. 840 Old Town Road, Bridgeport, CT 06606.

- Central Magnet (part of Central High School) is a public preparatory magnet school. It serves all Bridgeport applicants, who must meet grade requirements to enter the lottery. 1 Lincoln Blvd, Bridgeport, CT 06606.

Public military/trade high schools

- Bridgeport Military Academy (BMA) is for students looking for a career in public safety. Partnerships with local fire, police, Homeland Security and other departments. It is open to all Bridgeport applicants. 160 Iranistan Ave, Bridgeport, CT 06604.

- Bullard-Havens Technical High School is a vocational high school. It is a state school, not part of Bridgeport Public Schools.

Charter schools

edit- The Bridge Academy: Bridgeport Charter High School

- Achievement First Bridgeport Charter High School

- Great Oaks Charter School

- Park City Prep Charter School

Private education

editBridgeport is also home to private schools including Bridgeport Hope School (K–8), Bridgeport International Academy (grades 9–12), Catholic Academies of Bridgeport (Pre-K–8), Kolbe Cathedral High School (9–12), St. Andrew Academy (Pre-K–8), and St. Ann Academy (Pre-K–8).

Media

editRadio

edit- WCUM AM 1450; 1,000 watts (formerly WJBX-AM, and before that, WNAB-AM) Spanish Format station better known as Radio Cumbre.

- WICC-AM 600; 1,000 watts (daytime), 500 watts (nighttime) – WICC began broadcasting on November 21, 1926, when a previous radio station, WCWS, was given a new name, WICC. The last three letters standing for Industrial Capitol of Connecticut. The Bridgeport Broadcasting Company Inc. was the new station's owner. Back then, the station was powered at 500 watts. From 1951 to 1956 one of the station's radio hosts was Bob Crane, who later went on to play Col. Robert Hogan on the Hogan's Heroes television comedy series.[224] WICC's transmitter is on Pleasure Beach in Bridgeport on a peninsula extending into Long Island Sound.

- WEBE-FM 107.9; 50,000 watts. WEBE108 is Connecticut's Best Music Variety! The station is owned by Connoisseur Media. Licensed to Westport, CT with studios in Milford and WEBE's transmitter is located in Shelton. Besides a standard analog transmission, WEBE broadcasts over one HD Radio channel, and is available online.

- WEZN-FM 99.9; 27,500 watts (formerly WJZZ-FM). Star 99.9 is Today's Best Mix! The station is owned by Connoisseur Media. Lincensed to Bridgeport, CT with studios in Milford and WEZN's transmitter is located in Trumbull.

- WPKN-FM 89.5; 10,000 watts[225]

Newspapers

edit- Elsolnews.com, a community Spanish-language weekly newspaper covering news and events, based in Stamford.

- HaitianVoice.com, a Bridgeport-based newspaper covering local news in English, Haitian Creole and French.

- Brazil News covers stories from Bridgeport in Portuguese.[226]

- Connecticut Post – Formerly the Bridgeport Post and Bridgeport Telegram, which covers Bridgeport and the surrounding area. The newspaper is printed daily. It is owned by Hearst Connecticut Media.

Television

editBridgeport was NBC's pioneer UHF TV test site from December 29, 1949, to August 23, 1952;[227] the equipment from the "Operation Bridgeport" tests was later deployed commercially at KPTV in Portland, Oregon (1952–1957). While Bridgeport is primarily served by New York City or New Haven-Hartford stations, some local UHF broadcasters operate today:

- WEDW channel 49; one of the Connecticut Public Television stations, broadcasts from Bridgeport and can be seen in Hartford.

- In 2011, WTNH-TV opened a satellite studio in the offices of the Connecticut Post Downtown on State Street.

- WZME channel 43; a Story Television affiliate, currently channel sharing with WEDW and licensed to Bridgeport

Cable:

- News 12 Connecticut, an Altice-only cable news channel for local news and weather in Greater Bridgeport

Movies filmed in Bridgeport

editA list of films shot or partially filmed in the city:[citation needed]

- Officer Down (2012)

- A Dance for Grace (2010)

- Ironmen (2010)

- 3 Weeks to Daytona (2009)

- Accidental Mayor (2009)

- All Good Things (2009)

- Confessions of a Shopaholic (2009)

- Dear Beautiful (2009)

- The Godfather Musical Part III: Luca Brasi Sleeps with the Fishes (2009)

- House of Satisfaction (2009)

- Made for Each Other (2009)

- The Music of Erich Zann (2009/II)

- Old Dogs (2009/I)

- College Road Trip (2008)

- Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008)

- Pistol Whipped (2008)

- Righteous Kill (2008)

- The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 2 (2008)

- What Just Happened (2008)

- Bobby Dogs (2007)

- Dear Beautiful (2007)

- Praying to Hendrix (2007)

- Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995)

- A Walk with Death (1993)

- Route One USA (1989)

- There's a Nightmare in My Closet (1987)

- Without a Trace (1983)

- The Case of the Cosmic Comic (1976)

- The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds (1972)

- The Light that Failed (1916)

Television shows filmed in Bridgeport

edit- Kitchen Nightmares (Season 4, Episode 7, "Tavolini Restaurant", 2011)

- Brian Boitano Skating Spectacular (2010) (TV)

- Ghost Adventures:"Remington Arms Factory" (Episode 21, November 2009)

- WWE Raw (November 18, 2002; March 8, 2004; December 26, 2005; August 21, 2006; April 9, 2007; April 27, 2009; June 21, 2010, April 11, 2011, and September 17, 2012)

- WWE Smackdown, ECW, and NXT (May 7, 2002; March 4, 2003; August 2, 2005; December 9, 2008; November 24, 2009; November 2, 2010; and November 15, 2011)

- Oprah Winfrey Presents: Mitch Albom's For One More Day (2007)

- WWE Raw's 15th Anniversary Special (2007)

- Flip This House: "Burning Down the House" (2005)

- Extreme Makeover: Home Edition (2003 & 2007)