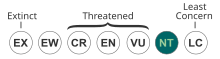

The black-billed gull (Chroicocephalus bulleri), also called Buller's gull or tarāpuka (Māori), is a Near Threatened species of gull in the family Laridae.[3][4][5] This gull is found only in New Zealand, its ancestors having arrived from Australia around 250,000 years ago.[6]: 89

| Black-billed gull | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Chroicocephalus |

| Species: | C. bulleri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chroicocephalus bulleri (Hutton, 1871)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Larus bulleri[2] | |

Taxonomy

editOriginally named Gavia pomare in 1855 by Carl Friedrich Bruch, the name was rejected by the New Zealand ornithologist Sir Walter Lawry Buller because it was already being used for another species.[7]: 58–59 He then took up Prince Napoléon Bonaparte's "playful" genus name Bruchigavia (literally, "Bruch's seabird")[8] as a provisional name for New Zealand gulls.[7]: 60 But because Buller's proposed species name melanoryncha (literally, "black-billed")[9]: 545 had already been given to another gull species, Frederick Hutton suggested the name bulleri, in honor of Buller, in 1871.[10][7]: 59 Buller accepted the offer and followed others in adopting the "larger and better-defined genus" of Larus.[7]: 59 The alternative common name Buller's gull also retains the connection to Buller.

The species is now considered to belong within the genus Chroicocephalus.[11][2] The holotype is in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.[12]

Description

editA healthy adult black-billed gull is typically 35–38 cm long, with a wingspan of 81–96 cm, and a weight of around 230g.[9]: 545 The head, body, and parts of the wings are white, with silvery grey on the saddle and wings, as well as black edging on the wings.[9]: 546 The gull also undergoes some seasonal color change. While typically black from February to June, the orbital ring is orange-red, red, or dark red the rest of the year.[9]: 556 The legs, too, change from black to dark red and even bright red as the breeding season progresses, "possibly stimulated by presence of begging chicks and juveniles."[9]: 556 Observations suggest the gull is sexually dimorphic, but there is a lack of published data to support this.[9]: 557 There is likewise a lack of data in regard to geographical variation.[9]: 557

Easily mistaken for the red-billed gull, the black-billed gull is distinguished by its black bill and is described as having a "more delicate appearance", a "more buoyant and graceful" flight, and being "generally less noisy", despite having a similar call.[9]: 546 F1 and F2 hybrids between the two gulls have been observed, both hybrids exhibiting dark red bills.[9]: 556

Behaviour

editColonies are formed around the first pair that begins nesting. Where more than one pair forms the initial nest, clustering around these sites takes place within the colony. Colonies are frequently tightly packed, with "Gulls little more than pecking distance from each other and nests often touch, leaving little room for taking off and landing".[9]: 550 Males may display aggressive behaviour towards others in an "ill-defined area"[9]: 550 for a few minutes before leaving the area and forgetting it. Nonetheless, not all male aggression is linked to defending a particular area, and some pairs without chicks will show aggression towards those with chicks. Fights are rarely prolonged, usually consisting of a single attack by the aggressor, employing the bill for pecking, the wings for beating, and the legs for scratching. The target typically retreats right away. Adults roost at the breeding colony or feeding sites, though the latter is more common.[9]: 551–52

Black-billed gulls can find themselves in conflict with humans. In 2024, black-billed gulls nesting near New Regent Street in Christchurch were deemed a "menace" by locals.[13] They had been nesting in the flooded foundations of a demolished office block nearby, and had spread to nesting on nearby rooftops.[13] The gulls were causing a nuisance by stealing food from tables and fouling the area.[13] A local café owner said, "They shit everywhere. They’re also not afraid of people any more. They’ll swoop down and get food off your plate. They dive bomb. Small children don't stand a chance."[13] Due to their protected status, nothing could be done to remove the birds.[13]

Distribution and habitat

editThe black-billed gull is endemic to New Zealand. Up to 78% of the total population is estimated to be living in the Southland region, on the southern end of the South Island.[14] In breeding season the gull is found on major rivers, especially braided rivers, lakes, and farmland. It generally prefers estuaries and coastal areas outside of the breeding season, though some can be found at breeding sites all year round. The gull is also attracted to urban areas, and "anywhere refuse of scraps available",[9]: 547 such as rubbish dumps and freezing works. In 2019 some gulls established a colony of around 300 birds in Christchurch Central City.[15] The species has been sighted occasionally on Stewart Island and The Snares, as well as at altitudes of up to 1700 MASL on the mainland.[9]: 546–47 Various colonies also live on the North Island, though it was formerly only a "visitor",[9]: 547 the first recorded breeding taking place at Lake Rotorua in 1932. Some South Island birds cross the Cook Strait after breeding season to winter in the North Island.[9][1]: 548–49

Important Bird Areas

editSites identified by BirdLife International as being important for black-billed gull conservation are:[16]

Status

editIn regard to Southland colonies, Rachel McClellan notes that "surveys in the 1970s indicated a population of about 140,000 breeding birds, whereas recent counts gave estimates of only 15–40,000 breeding birds".[17]: 13 This suggests a 6% decline in population every year across thirty years, equivalent to up to 83.6% over the whole period, or 50% if the data are taken conservatively.[17]: 26, 174 Higher population sizes in the 1950s and 1960s were potentially the result of increased agricultural activity, but the correlation is tenuous.[17]: 13 Populations at this time were of legendary proportions, with anecdotes telling of farmers who "were forced to wear raincoats so as not to be coated in droppings".[6]: 89

Due to "very rapid decline over three generations" the IUCN has rated the species as Near Threatened.[1] The gull had earlier received a Least Concern rating in 1994, and a Vulnerable rating in 2000.[17]: 13–14 The New Zealand Department of Conservation listed the gull as Nationally Critical in 2016.[18] It has been referred to in other publications as "critically endangered",[6]: 89 [19][20] and James Westrip proposed in August 2018 that the gull's status be uplisted to Critically Endangered in the next BirdLife International Red List report, though it was eventually downlisted in 2020.[21] Bill Morris calls the bird "the world's rarest gull".[6]: 90

Threats

editIn her study of Southland colonies of black-billed gulls, Rachel McClellan found that eighty per cent of observed chick deaths resulted from predation.[17]: 105 Introduced mammals, namely ferrets, stoats, cats, and hedgehogs, constitute the "primary factor influencing productivity", that is, nest success, in the colonies.[17]: 147 Chick predation from the indigenous black-backed gull (Larus dominicanus) also threatens the black-billed gull population.[17]: 112–13

While "the species is relatively tolerant of human disturbance",[17]: 187 having potentially benefitted from increasing land conversion for agricultural use since the arrival of Europeans, human activity has also had a negative impact on population size. Largescale shootings of black-billed gulls, such as a 2009 "massacre" of around 200 birds in North Canterbury,[22] are particularly detrimental to the species' future.[17]: 197 A similar event was reported in December 2018,[23] while another article tells of a gull being discovered with an arrow in it.[20] The birds have also been targeted by people in vehicles who "occasionally plough through colonies".[6]: 88 Morris suggests such actions in part result from confusion with the more common and disliked red-billed gull (Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae scopulinus), which is nonetheless also endangered in New Zealand.[6]: 88, 94–94 Although no studies have been conducted in this area, previous DDT usage on farms may affect the breeding success of black-billed gulls and herbicides that remain in use could have consequences that are yet unknown.[17]: 188

McClellan suggests that climate change could have a positive impact on black-billed gull populations, such as in encouraging earlier or extended breeding seasons, but also a negative impact in increasing food availability, which would result in "poor synchrony".[17]: 183 Nesting on river islands, chicks are also vulnerable to flooding. In a January 2018 flood, a single colony lost up to 2500 chicks.[24] Another colony is thought to have lost around 2200 eggs in a flood in November the same year.[25]

In October 2019, Mike Turner responded to a proposal for commercial rafting along the Mataura River, citing concerns for the welfare of black-billed gulls.[26]

Conservation efforts

editIn October 2018, the Department of Conservation began a trial cull of black-backed gulls along the Hurunui River to control predation of black-billed gull chicks and other threatened bird species.[27] In August 2019, after a successful trial, the department announced a five-year programme extending to the Waiau Uwha River that aims to reduce the black-backed gull population in the areas by at least eighty per cent.[28]

The black-billed gull placed 30th, with 441 votes, in Forest & Bird's 2018 Bird of the Year competition.[29][30][31]

Gallery

edit-

Gull chicks collected in 1934

-

Immature gull

-

1873 illustration of black-billed gull and black-backed gull

-

Gull specimen collected in 1930

-

Wing specimen collected in 2004

-

1888 woodcut of black-billed gull's outer primary feathers

References

edit- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2020). "Larus bulleri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22694413A176994991. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22694413A176994991.en.

- ^ a b "Chroicocephalus bulleri (Hutton, 1871)". Catalogue of Life. Species 2000: Leiden, the Netherlands.

- ^ McClellan, R. K.; Habraken, A. (2017) [2013]. "Black-billed gull". New Zealand Birds Online. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ McBride, Abby (31 January 2018). "Just a Seagull? Nope". National Geographic Blog.

- ^ McBride, Abby (2012). Don't Call It a Seagull! (Masters). MIT.

- ^ a b c d e f Morris, Bill (January–February 2019). "Tending the Flock". New Zealand Geographic. Vol. 155.

- ^ a b c d Buller, Walter Lawry (1888). A History of the Birds of New Zealand (2nd ed.). London. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). Helm's Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names: From Aalge to Zusii. London: Christopher Helm. p. 78. ISBN 9781408133262.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Higgins, P. J.; Davies, S. J. J. F., eds. (1996). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds: Volume 3: Snipe to Pigeons. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195530704.

- ^ Norman, Geoff (2018). Birdstories: A History of the Birds of New Zealand. Nelson, New Zealand: Potton & Burton. p. 170. ISBN 9780947503925.

- ^ "Black-billed Gull: Chroicocephalus bulleri (Hutton, FW, 1871)". AviBase.

- ^ "Black-billed Gull, Larus bulleri Hutton, 1871". collections.tepapa.govt.nz. Te Papa. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Law, Tina (10 November 2024), "Menace gulls turn tourist hot spot into 'eyesore'", The Press, retrieved 10 November 2024

- ^ Hutching, Gerard (17 February 2015). "Red and black-billed gulls". teara.govt.nz. Te Ara. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ Gates, Charlie (5 November 2019). "Urban bird colony in ruins of former office block in Christchurch". Stuff.co.nz.

- ^ "Black-billed Gull (Larus bulleri)". birdlife.org. BirdLife International. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k McClellan, Rachel Katherine (2009). The Ecology and Management of Southland's Black-billed Gulls (PhD). University of Otago. Nonetheless, different counting methods and the various limitations of these methods mean that "estimates must be treated with caution".

- ^ Robertson, Hugh A.; et al. (2017). "Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2016" (PDF). New Zealand Department of Conservation.

- ^ Popenhagen, Courtney (9 January 2024). "Waimakariri River Regional Park Braided River Bird Management 2016–2017 Season" (PDF). BRaid. Environment Canterbury: Regional Council. p. 2.

- ^ a b Hudson, Daisy (3 January 2017). "Critically endangered black-billed gull shot with arrow in Timaru". Stuff.co.nz.

- ^ Westrip, James (23 August 2018). "Black-billed Gull (Larus bulleri): revise global status?". BirdLife International: Globally Threatened Bird Forums. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Massacre of native rare birds". Stuff.co.nz. 18 February 2009.

- ^ Dangerfield, Emma (19 December 2018). "Shooting ends breeding season for endangered gulls on Waimakariri River". Stuff.co.nz.

- ^ Cann, Ged (15 January 2018). "The world's most threatened gull calls New Zealand home, but most Kiwis don't know it". Stuff.co.nz.

- ^ Dangerfield, Emma (28 November 2018). "Flooding destroys hopes for boost in North Canterbury black-billed gull population". Stuff.co.nz.

- ^ Rowe, Damian (13 October 2019). "Fish & Game to seek public notification on section of rafting proposal". Stuff.co.nz.

- ^ "Control of black-backed gulls to protect rare braided river birds". New Zealand Department of Conservation. 29 October 2018.

- ^ "Rare braided river birds to be protected by gull control". New Zealand Department of Conservation. 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Kereru crowned Bird of the Year for 2018". Forest & Bird. 15 October 2018.

- ^ "Fowl play all aflutter in Bird of the Year competition". The New Zealand Herald. 18 October 2017.

- ^ "Enough of this nest-feathering politics". Stuff.co.nz. 20 October 2017.