The term "big cat" is typically used to refer to any of the five living members of the genus Panthera, namely the tiger, lion, jaguar, leopard, and snow leopard, as well as the non-pantherine cheetah and cougar.[1][2]

| Big cats | |

|---|---|

| |

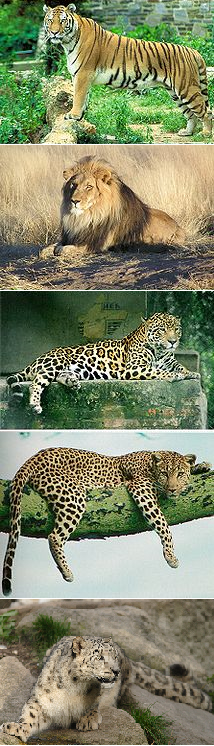

| Images of the members of the genus Panthera, from top to bottom: the tiger, the lion, the jaguar, the leopard, and the snow leopard. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Superfamily: | Feloidea |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Species | |

All cats descend from the Felidae family, sharing similar musculature, cardiovascular systems, skeletal frames, and behaviour. Both the cheetah and cougar differ physically from fellow big cats, and to a greater extent, other small cats. As obligate carnivores, big cats are considered apex predators, topping their food chain without natural predators of their own.[3][4] Native ranges include the Americas, Africa, and Asia; the ranges of the leopard and tiger also extend into Europe, specifically in Russia.[5]

Species

editEvolution

editIt is estimated that the ancestors of most big cats split away from the Felinae about 6.37 million years ago.[6] The Felinae, on the other hand, comprises mostly small to medium-sized cats, including domestic cats, but also some larger cats such as the cougar and cheetah.[7]

A 2010 study published in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution has given insight into the exact evolutionary relationships of the big cats.[8] The study reveals that the snow leopard and the tiger are sister species, while the lion, leopard, and jaguar are more closely related to each other. The tiger and snow leopard diverged from the ancestral big cats approximately 3.9 Ma. The tiger then evolved into a unique species towards the end of the Pliocene epoch, approximately 3.2 Ma. The ancestor of the lion, leopard, and jaguar split from other big cats from 4.3–3.8 Ma. Between 3.6 and 2.5 Ma, the jaguar diverged from the ancestor of lions and leopards. Lions and leopards split from one another approximately 2 Ma.[9] The earliest big cat fossil, Panthera blytheae, dating to 4.1−5.95 MA, was discovered in southwest Tibet.[10]

| 3.9 Ma |

| ||||||

Description and abilities

editRoaring

editThe ability to roar comes from an elongated and specially adapted larynx and hyoid apparatus.[11] The larynx is attached to the hyoid bone that is hanging from a sequence of bones. This sequence of bones the hyoid hangs from are tympanohyal, stylohyal, epihyal, and ceratohyal; these are located in the mandible and skull.[12] In the larynx, there are vocal folds that produce the structure needed to stretch the ligament to a length that creates the roar effect. This tissue is made of thick collagen and elastic fiber that becomes denser as it approaches the epithelial mucosal lining.[13] When this large pad folds it creates a low natural frequency, causing the cartilage walls of the larynx to vibrate. When it begins to vibrate the sound moves from a high to low air resistance which makes the roaring.

The lion's larynx is the longest, giving it the most robust roar. The roar in good conditions can be heard 8 or even 10 km (5 or 6 mi) away.[14] All five extant members of the genus Panthera contain this elongated hyoid but owing to differences in the larynx the snow leopard cannot roar. Unlike the roaring cats in their family, the snow leopard is distinguished by the lack of a large pad of fibro-elastic tissue that allows for a large vocal fold.

Weight range

editThe range of weights exhibited by the species is large. At the bottom, adult snow leopards usually weigh 22 to 55 kg (49 to 121 lb), with an exceptional specimen reaching 75 kg (165 lb).[15][16]

Male and female lions typically weigh 150–250 kg (330–550 lb) and 110–182 kg (243–401 lb) respectively,[17][18] and male and female tigers 100–306 kg (220–675 lb) and 75–167 kg (165–368 lb) respectively.[19] Exceptionally heavy male lions and tigers have been recorded to exceed 306 kg (675 lb) in the wilderness,[20][21] and weigh around 450 kg (990 lb) in captivity.[20][22]

The liger, a hybrid of a lion and tiger, can grow to be much larger than its parent species. In particular, a liger called 'Nook' is reported to have weighed over 550 kg (1,210 lb).[23][24]

Interaction with humans

editConservation

editAn animal sanctuary provides a refuge for animals to live out their natural lives in a protected environment. Usually, these animal sanctuaries are the organizations which provide a home to big cats whose private owners are no longer able or willing to care for their big cats. However, the use of the word sanctuary in an organization's name is by itself no guarantee that it is a true animal sanctuary in the sense of a refuge. To be accepted by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) as a bona fide animal sanctuary and to be eligible for an exemption from the prohibition of interstate movement of big cats under the Captive Wildlife Safety Act (CWSA), organizations must meet the following criteria:[25]

- Must be a non-profit entity that is tax-exempt under section 501(a) of the Internal Revenue Code

- Cannot engage in commercial trade in big cat species, including their offspring, parts, and products made from them

- Cannot breed big cats

- Cannot allow direct contact between big cats and the public at their facilities

- Must keep records of transactions involving covered cats

- Must allow the service to inspect their facilities, records, and animals at reasonable hours

Internationally, a variety of regulations are placed on big cat possession.[26] In Austria, big cats may only be owned in a qualified zoo which is overseen by a zoologist or veterinarian.[27] Requirements must also be met for enclosures, feeding, and training practices. Both Russia and South Africa regulate private ownership of big cats native to each country. Some countries, including Denmark, Thailand and India, prohibit all private ownership of big cats.[26]

Threats

editThe members of the Panthera genus are classified as some level of threatened by the IUCN Red List: the lion,[28] leopard[5] and snow leopard[29] are categorized as Vulnerable; the tiger is listed as Endangered;[30] and the jaguar is listed as Near Threatened.[31] Cheetahs are also classified as Vulnerable,[32] and the cougar is of Least Concern.[33] All species currently have populations that are decreasing. The principal threats to big cats vary by geographic location but primarily consist of habitat destruction and poaching. In Africa, many big cats are hunted by pastoralists or government "problem animal control" officers. Certain protected areas exist that shelter large and exceptionally visible populations of African leopards, lions and cheetahs, such as Botswana's Chobe, Kenya's Masai Mara, and Tanzania's Serengeti; outside these conservation areas, hunting poses the dominant threat to large carnivores.[34]

In the United States, 19 states have banned ownership of big cats and other dangerous exotic animals as pets, and the Captive Wildlife Safety Act bans the interstate sale and transportation of these animals.[35] The initial Captive Wildlife Safety Act (CWSA) was signed into law on December 19, 2003.[36] To address problems associated with the increasing trade in certain big cat species, the CWSA regulations were strengthened by a law passed on September 17, 2007.[37] The big cat species addressed in these regulations are the lion, tiger, leopard, snow leopard, clouded leopard, cheetah, jaguar, cougar, and any hybrid of these species (liger, tigon, etc.). Private ownership is not prohibited, but the law makes it illegal to transport, sell, or purchase such animals in interstate or foreign commerce. Although these regulations seem to provide a strong legal framework for controlling the commerce involving big cats, international organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) have encouraged the U.S. to further strengthen these laws. The WWF is concerned that weaknesses in the existing U.S. regulations could be unintentionally helping to fuel the black market for tiger parts.[38]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Davis, B.W.; Li, G.; Murphy, W.J. (2010). "Supermatrix and species tree methods resolve phylogenetic relationships within the big cats, Panthera (Carnivora: Felidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (1): 64−76. Bibcode:2010MolPE..56...64D. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.036. PMID 20138224.

- ^ Turner, Alan; Anton, Mauricio (1997). The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives (Illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-0-231-10228-5. OCLC 34283113.

- ^ Balme, G. (2005). "Counting Cats" (PDF). Africa Geographic (13): 36−43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-13.

- ^ Ordiz, Andrés; Bischof, Richard; Swenson, Jon E. (2013-12-01). "Saving large carnivores, but losing the apex predator?". Biological Conservation. 168: 128–133. Bibcode:2013BCons.168..128O. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2013.09.024. hdl:11250/2492589. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ a b Stein, A.B.; Athreya, V.; Gerngross, P.; Balme, G.; Henschel, P.; Karanth, U.; Miquelle, D.; Rostro-Garcia, S.; Kamler, J.F.; Laguardia, A.; Khorozyan, I.; Ghoddousi, A. (2020) [amended version of 2019 assessment]. "Panthera pardus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T15954A163991139. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T15954A163991139.en. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Joseph Stromberg (2013-11-12). "This Fossil Skull Unearthed in Tibet Is the Oldest Big Cat Ever Found". Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–545. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Davis, Brian W.; Li, Gang & Murphy, William J. (2010). "Supermatrix and species tree methods resolve phylogenetic relationships within the big cats, Panthera (Carnivora: Felidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (1): 64–76. Bibcode:2010MolPE..56...64D. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.036. PMID 20138224.

- ^ "Tiger's ancient ancestry revealed". BBC News. 2010-02-12. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Z. Jack Tseng; Xiaoming Wang; Graham J. Slater; Gary T. Takeuchi; Qiang Li; Juan Liu; Guangpu Xie (7 January 2014). "Himalayan fossils of the oldest known pantherine establish ancient origin of big cats". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 281 (177 4): 20132686. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2686. PMC 3843846. PMID 24225466.

- ^ Weissengruber, GE; G Forstenpointner; G Peters; A Kübber-Heiss; WT Fitch (September 2002). "Hyoid apparatus and pharynx in the lion (Panthera leo), jaguar (Panthera onca), tiger (Panthera tigris), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), liger (Panthera leo × Panthera tigris), Tigon (Panthera tigris x Panthera leo) and the domestic cat. (Felis silvestris f. catus)". Journal of Anatomy. 201 (3): 195–209. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00088.x. PMC 1570911. PMID 12363272.

- ^ Hast, M H (April 1989). "The larynx of roaring and non-roaring cats". Journal of Anatomy. 163: 117–121. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1256521. PMID 2606766.

- ^ Erickson-DiRenzo, Elizabeth; Sivasankar, M. Preeti; Thibeault, Susan L. (2014-12-15). "Utility of cell viability assays for use with ex vivo vocal fold epithelial tissue". The Laryngoscope. 125 (5): E180 – E185. doi:10.1002/lary.25100. ISSN 0023-852X. PMC 4414688. PMID 25511412.

- ^ Kathy Darling (1 January 2000). Lions. Lerner Publications. ISBN 978-1-57505-404-9.

- ^ Sunquist, M.; Sunquist, F. (2002). "Snow leopard". Wild Cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 377–394. ISBN 978-0-226-77999-7.

- ^ Boitani, L. (1984). Simon & Schuster's Guide to Mammals. Simon & Schuster, Touchstone Books. ISBN 978-0-671-42805-1.

- ^ Nowell, Kristin; Jackson, Peter (1996). Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (PDF). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 1–334. ISBN 978-2-8317-0045-8.

- ^ Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- ^ Mazák, V. (1981). "Panthera tigris". Mammalian Species (152): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504004. JSTOR 3504004.

- ^ a b Wood, G. L. (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ "East African Business Digest", University Press of Africa, with contributions from the Kenya National Chamber of Commerce & Industry, 1963, retrieved 2018-03-18

- ^ "The Nineteenth Century and After". Vol. 130. Leonard Scott Publishing Company. 1941. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ^ "The Liger - Meet the World's Largest Cat". Liger Facts. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ^ "Liger Nook - Liger Profile". Liger World. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ^ "Captive Wildlife Safety Act - What Big Cat Owners Need to Know" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Law Enforcement.

- ^ a b Zhang, Laney; Palmer (2013). "Regulations Concerning the Private Possession of Big Cats: Comparative Analysis | Law Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Palmer, Edith (2013). "Regulations Concerning the Private Possession of Big Cats: Austria| Law Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ Bauer, H.; Packer, C.; Funston, P.F.; Henschel, P.; Nowell, K. (2017) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Panthera leo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15951A115130419. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T15951A107265605.en.

- ^ McCarthy, T.; Mallon, D.; Jackson, R.; Zahler, P.; McCarthy, K. (2017). "Panthera uncia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22732A50664030. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T22732A50664030.en.

- ^ Goodrich, J.; Lynam, A.; Miquelle, D.; Wibisono, H.; Kawanishi, K.; Pattanavibool, A.; Htun, S.; Tempa, T.; Karki, J.; Jhala, Y.; Karanth, U. (2015). "Panthera tigris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T15955A50659951. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T15955A50659951.en.

- ^ Quigley, H.; Foster, R.; Petracca, L.; Payan, E.; Salom, R.; Harmsen, B. (2018) [errata version of 2017 assessment]. "Panthera onca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T15953A123791436. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15953A50658693.en.

- ^ Durant, S.; Mitchell, N.; Ipavec, A.; Groom, R. (2015). "Acinonyx jubatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T219A50649567. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T219A50649567.en.

- ^ Nielsen, C.; Thompson, D.; Kelly, M.; Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A. (2016) [errata version of 2015 assessment]. "Puma concolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T18868A97216466. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T18868A50663436.en. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Hunter, Luke (June 2004). "Carnivores in Crisis: The Big Cats" (PDF). Africa Geographic: 28–41. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 15, 2010.

- ^ Pacelle, Wayne. "Captive Wildlife Safety Act: A Good Start in Banning Exotics as Pets". The Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on 19 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- ^ "Captive Wildlife Safety Act: What Big Cat Owners Need to Know" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 2008-09-22. Retrieved 2024-04-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Regulations To Implement the Captive Wildlife Safety Act" (PDF). Federal Register. 72 (158). U.S. Congress. August 16, 2007. Archived from the original on September 22, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Braun, David (October 21, 2010). "America's 5,000 Backyard Tigers a Ticking Time Bomb, WWF Says". News Watch. National Geographic. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2023.