Bellshill (pronounced "Bells hill") is a town in North Lanarkshire in Scotland, ten miles (sixteen kilometres) southeast of Glasgow city centre and 37 mi (60 km) west of Edinburgh. Other nearby localities are Motherwell 2 mi (3 km) to the south, Hamilton 3 mi (5 km) to the southwest, Viewpark 1+1⁄2 mi (2.5 km) to the west, Holytown 2 mi (3 km) to the east and Coatbridge 3 mi (5 km) to the north.

Bellshill

| |

|---|---|

St. Andrew's Church, Bellshill | |

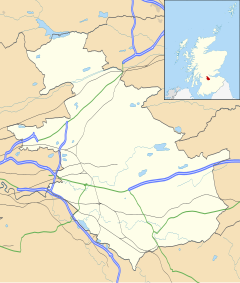

Location within North Lanarkshire | |

| Population | 19,700 (2022)[2] |

| OS grid reference | NS730575 |

| • Edinburgh | 33 mi (53 km) ENE |

| • London | 341 mi (549 km) SSE |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BELLSHILL |

| Postcode district | ML4 |

| Dialling code | 01698 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

The town of Bellshill (including the villages of Orbiston and Mossend) has a population of about 20,650.[3][4] From 1996 to 2016, it was considered to be part of the Greater Glasgow metropolitan area. Since then it has been counted as part of a continuous suburban settlement anchored by Motherwell, with a total population of around 125,000.

History

editThe earliest record of Bellshill's name is handwritten on a map by Timothy Pont dated 1596; the letters are difficult to distinguish.[5] It's possible that it reads Belſsill with the first s being an old-fashioned long s. The site is recorded as being east of "Vdinſtoun" and north of "Bothwel-hauch" (which confusingly is above "Orbeſton" on Pont's map).[6] The name can also been seen on a map, which was derived from Pont's work, made by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu; he calls the place "Belmil".[7] The village consisted of a row of quarry workers' houses owned by a Mr. Bell, who owned a stone quarry to the south of Belmill.[8] Charles Ross's map of 1773 has "Belsihill" marked north of Crosgates and Orbiston.[9]

About 1810, this new settlement took on the name Bellshill[10] and continued to grow. It absorbed nearby villages such as Nesnas, Black Moss and Sykehead.[11] Bellshill was on the road which linked Glasgow and Edinburgh.[12]

According to the first Statistical Account, in the late 1700s the parish of Bothwell, which encompasses modern Bellshill, was a centre of hand-loom weaving with 113 weavers recorded. Some 50 colliers were listed.[13] A hundred or so years later, these occupations had changed places in degree of importance to the area economy. With the introduction of new machinery in the mid-19th century, many cottage weavers lost their livelihood. Demand for coal to feed British industry resulted in expansion that by the 1870s, produced 20 deep pits operating in the area.[14]

The first mine to open (and the last to close in 1953) was the Thankerton mine.[15] Others followed swiftly and rapidly increased the size of the town, attracting a steady stream of immigrant workers from abroad, particularly from Ireland and Lithuania.[16][17] The town is sometimes referred to as 'Little Lithuania' because of these immigrants.[18] (Historically it was called 'Little Poland', as contemporary evidence shows locals did not work to distinguish incomers' backgrounds).[19][20] Factors adversely affecting integration for the first generation of these 'new Scots' included a language barrier, minority religion (most were Catholic), and hostility based on suspicion that they were taking jobs, by accepting lower wages and being used to break strikes.[16][21] – Lithuanians in Bellshill and elsewhere tended to identify more closely with the Irish communities of each town, who had similar issues.[22]

The rise in the migrant population (though severely lessened by the political changes following the First World War and subsequent Russian Revolution, which adversely affected the status of Lithuanians both in their homeland and in Britain)[21][23] resulted in their opening The Scottish Lithuanian Recreation and Social Club on Calder Road in the Mossend area.[24][20] Gradually Lithuanian culture has faded over the decades, as families have assimilated into Scottish life. Younger generations sometimes are unaware of their family's history, also because of intermarriage, name changes and anglicisation of distinctive surnames (either voluntarily or by obligation).[19][20]

Among the most famous of the descendants of this community was footballer Billy McNeill of Celtic and Scotland.[25] Other mid-20th century players of Lithuanian heritage included Andy Swallow, Alex Millar, Matt Balunas, and John Jack.[22]

Iron and steel production were also central to the development of the town through the 19th century.[26] J. B. Neilson, developer of the revolutionary 'hot blast' process, opened the first iron works in the area (Mossend Iron Works) in 1839.[14]

During the industrial boom there were a number of railway stations, including Mossend, Fallside and Bell Cross.[27] The settlement is now served solely by Bellshill railway station.

Maternity services were provided at Bellshill Maternity Hospital until the hospital was closed in 2001.[28]

According to a report by the Halifax Building Society, in the first quarter of 2005 Bellshill was the UK's property hot spot with a 46% rise in house prices. This took the average property price to £105,698 (according to reports published April 2005).

Reflecting an increase in new Muslim immigrant populations from east Asia, in 2006, a new mosque was opened in the Mossend area of Bellshill. It has become one of the largest mosques in Scotland.[29]

The streetscape project, a plan to regenerate and modernise the town centre, commenced Apr 2007 and was completed nearly three years later. The project, created a one-way system on the main street and provided more space for pedestrians.

Education

editBellshill once had six primary schools, including Belvidere Primary School.[30] This was closed in early June 2010 and has now been demolished.

Holy Family Primary School was founded in 1868. It moved to new buildings in 1907 to accommodate the influx of Lithuanian, Polish and Irish Catholics seeking work in the area. Other primary schools include Sacred Heart Primary, Mossend Primary, Noble Primary, St. Gerard's Primary, and Lawmuir Primary.

There are two fairly large secondary schools, Bellshill Academy[31] and Cardinal Newman High School, a Catholic school.[32]

Religion

editHistorically a Relief Church for 1000 people was built in Bellshill in 1763.[33] Today several churches serve the town. St Andrews United Free Church of Scotland sits at Bellshill Cross whilst the Church of Scotland parish churches are at opposite ends of the Main Street. Bellshill Central Parish church is opposite The Academy, and Bellshill West Parish Church[34] is next to the Sir Matt Busby Sports Centre. The town's Roman Catholic parish churches are St Gerard's, Sacred Heart, and Holy Family, Mossend.

Transport

editBellshill lies at an important point on Scotland's motorway network, situated around 1+1⁄2 miles (2.5 kilometres) south of the M8 motorway between Glasgow and Edinburgh and their respective airports. It is about the same distance north of the M74 motorway to and from England; the A725 road running directly to the west of the town links the two.

The presence of this busy transport corridor and the availability of land following the decline of older heavy industry has led to the development of two large, modern industrial estates (Bellshill and Righead) flanking the A725. The Eurocentral industrial and distribution park is about 1+1⁄2 miles (2.5 kilometres) northeast of the town, and also features a railway freight terminal. Once heavily reliant on the railways relating to coal mining, Bellshill is still served by a rail junction to the east of Mossend; it connects two of the main passenger routes covering southern, western and central Scotland Argyle Line –and Shotts Line – both of which stop at Bellshill railway station in the town centre.

Culture

editThe Bellshill Cultural Centre has a free library. Various singers, such as Sheena Easton, and sportsmen such as Sir Matt Busby and Billy McNeill hailed from the town (a statue of McNeill at Bellshill Cross was unveiled in 2022).[35][36]

Music

editBellshill is also known for its music, especially since the mid-1980s. Bands such as the Soup Dragons, BMX Bandits, and Teenage Fanclub put Bellshill on the map as an indie rock hot-spot in Scotland. The scene - known as the Bellshill Sound or the Bellshill Beat - was celebrated by influential DJ John Peel in the Channel 4 television series Sounds Of The Suburbs.

Bellshill continues to produce well respected and influential independent pop music, with members of Mogwai and De Rosa hailing from the town. Sheena Easton was also from the town, and attended Bellshill Academy.

Sport

editThe town has a football team, Bellshill Athletic,[37] that plays in the West of Scotland Football League. The club won promotion to the Second Division in 2024 after finishing 3rd behind Lanark United and Lesmahagow. They play their home games at Rockburn park. They had moved from Tollcross, Glasgow, after New Brandon Park was closed to reduce costs.

Bellshill also has the Sir Matt Busby Sports Complex that opened in 1995. (It is named after the late Manchester United legend who was born and brought up in the area). It has a 25m swimming pool, with two large spectator seating areas either side, a large hall, and health suite. The complex also has a gym and a dance studio.

A golf course is located next to nearby Strathclyde Park, which is within walking distance of parts of the town, particularly Orbiston. The Greenlink Cycle Path passes through the golf course and the Orbiston area of Bellshill, heading towards Forgewood.

Notable people from Bellshill

editThe following list refers to notable people who were born in Bellshill, although they did not necessarily reside there. The town was home to Lanarkshire's maternity hospital in the latter part of the 20th century.

- Jackie Bird, journalist and broadcaster[38]

- Doug Cameron, Australian politician

- Gregory Clark, economist

- Thomas Clark, poet

- Robin Cook, politician[39]

- James Dempsey, politician

- Henry Dyer, engineer

- Sheena Easton, vocalist[38]

- Aminatta Forna, (OBE), award-winning writer of novels, memoir, and essays

- Catherine Grubb, artist[40][41]

- Charles Jeffrey, fashion designer

- Bryan Kirkwood, television producer

- Monica Lennon, politician

- Eric McCormack, writer

- John McCusker, musician

- Ethel MacDonald, anarchist[38]

- Paul McGuigan, filmmaker

- David MacMillan, Nobel Prize winning chemist[42]

- Billy Moffatt, footballer

- David Shaw Nicholls, architect and designer

- Sean O'Kane, actor and model

- William Orr, trade unionist

- John Reid, politician

- James Cleland Richardson, soldier – Victoria Cross recipient

- Natalie J. Robb, actress

- Sharleen Spiteri, musician – lead vocalist of Texas

- Harry Stanley, innocent man killed by police

Sportspeople

edit- Kenny Arthur, footballer

- Tom Birney, American football player

- Sir Matt Busby, Scotland international football player and manager[38]

- Stuart Carswell, footballer

- William Chalmers, football player and manager

- Peter Cherrie, footballer

- Tom Cowan, footballer

- Mike Denness, international cricketer[43]

- Alex Dickson, boxer

- Scott Fox, footballer

- Hughie Gallacher, Scotland international footballer[44]

- Kirsty Gilmour, badminton player[45]

- Peter Grant, Scotland international footballer

- Scott Harrison, former world boxing champion[46]

- Lee Hollis, footballer

- Jackie Hutton, football player and manager

- Brian Irvine, Scotland international footballer

- Peter Jack, cricketer

- Russell Jones, cricketer

- Brian Kerr, Scotland international footballer

- David Lilley, footballer

- Malky Mackay, Scotland international football player and manager

- Chris Maguire, Scotland international footballer

- Kevin McBride, footballer

- Brian McClair, Scotland international footballer

- Ally McCoist, Scotland international football player and manager[47]

- Lee McCulloch, footballer

- Chris McGroarty, footballer

- Tom McKean, Olympic track athlete[38]

- Billy McNeill, Scotland international football player and manager[25]

- James McPake, football player and manager

- Hugh Murray, footballer

- Alex Neil, football player and manager

- Phil O'Donnell, Scotland international footballer

- Tommy O'Hara, United States international footballer

- Jim Paterson, footballer

- Anthony Ralston, footballer

- John Rankin, footballer

- Shaun Rooney, footballer

- Steven Smith, footballer

- John Stewart, footballer

- Andy Swallow, footballer

- Bob Wilson, footballer

- Kenny Wright, footballer

Bands from Bellshill

editReferences

edit- ^ a b List of railway station names in English, Scots and Gaelic Archived 22 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine - NewsNetScotland

- ^ "Mid-2020 Population Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland". National Records of Scotland. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Key Facts 2016 - Demography". North Lanarkshire Council. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Estimated population of localities by broad age groups, mid-2012" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Glasgow and the county of Lanark - Pont 34". Maps of Scotland. Timothy Pont (16th century). Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ "Bellshill on Pont's map no. 34". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Blaeu, Joan. "Glottiana Praefectura Inferior". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "1986 - BELLSHILL AND MOSSEND". BBC. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ "County Maps". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Six Inch Maps". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "25-inch O.S. Map with zoom and Bing overlay". National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Lewis, Samuel (1851). A topographical dictionary of Scotland, comprising the several counties, islands, cities, burgh and market towns, parishes, and principal villages, with historical and statistical descriptions: embellished with engravings of the seals and arms of the different burghs and universities. London: S. Lewis and co. p. 123. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Macculloch, Michael (1795). The statistical account of Scotland. Drawn up from the communications of the ministers of the different parishes (Vol 16 ed.). Glasgow: Dunlop and Wilson. p. 304. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ a b Wilson, Rhona (1995). Bygone Bellshill. Catrine, Ayrshire: Stenlake Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 9781872074597. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Rhona (1995). Bygone Bellshill. Catrine, Ayrshire: Stenlake Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 9781872074597. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ a b Lithuanian miners in Scotland: migration and misconceptions, Prof Marjory Harper (University of Aberdeen), Our Migration Story

- ^ Lithuanians in Glasgow, The Guardian, 22 January 2006

- ^ "Lithuanians in Lanarkshire". Legacies: UK history local to you. BBC. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ a b "The When, How, and Why of the Lithuanians in Scotland", John Millar, Draugas News, 15 September 2006

- ^ a b c Migration: Lithuania to North Lanarkshire, CultureNL

- ^ a b NQ Higher Scottish History | Difficulties faced by Lithuanian immigrants, Education Scotland

- ^ a b "Every footballer has a story, especially if he played for Celtic", Michael Beattie, Celtic Quick News, 11 March 2017

- ^ Lithuanian Incomers to Blantyre, Paul Veverka, The Blantyre Project, 2 December 2019

- ^ Fisher, Jack (1995). Old Bellshill in pictures. Motherwell: Motherwell Leisure. p. 47. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ a b "A national hero in Scotland… and Lithuania: Vilnius hails Celtic legend Billy McNeill’s family roots in Eastern Europe", Stacey Mullen, Sunday Post, 5 May 2019

- ^ Mort, Frederick (1910). Lanarkshire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 152. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Groome, Francis Hindes (1895). Ordnance gazetteer of Scotland: a survey of Scottish topography, statistical, biographical, and historical. London: W. Mackenzie. p. 140. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ "Maternity staff reunion just the start". Motherwell Times. 28 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Google Mosque Map - UK Mosques Directory". mosques.muslimsinbritain.org.

- ^ "1986 - EDUCATION". BBC. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ Fisher, Jack (1995). Old Bellshill in pictures. Motherwell: Motherwell Leisure. pp. 39–40. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "1986 - COMPREHENSIVE EDUCATION". BBC. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ Gardiner, Matthew (1845). The new statistical account of Scotland. Edinburgh and London: W. Blackwood and Sons. p. 800. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ "Church celebrates 140th anniversary". Motherwell Times. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Meikle, David (23 July 2020). "Campaign for Celtic legend Billy McNeill statue in his hometown smashes £70k fundraising target". The Daily Record. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "Billy McNeill statue unveiled as Celtic icon remembered in hometown with Lisbon Lion memorial", Mark Pirie, Daily Record, 26 November 2022

- ^ "Soccer's spirit withers in Busby's birthplace", John Arlidge, The Independent, 22 October 2011

- ^ a b c d e "Bellshill from The Gazetteer for Scotland". www.scottish-places.info. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Obituary: Robin Cook". BBC News. 6 August 2005. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Catherine Grubb". Government Art Collection. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Etchings and Drawings by Catherine Grubb" (PDF). The Questors Archives. The Questors Theatre. 1993. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Former Glasgow University student wins the Nobel prize for chemistry". Glasgow Times. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Obituary: Mike Denness OBE, cricketer". www.scotsman.com. 20 April 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Hughie Gallacher: The glory and tragedy of a Newcastle United and Scotland legend". www.scotsman.com. 18 March 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "Badminton star sent rape and death threats from gamblers". BBC News. 2 April 2023. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "Former world champion Scott Harrison makes comeback". www.scotsman.com. 24 June 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "McCoist leaves Rangers manager post". BBC Sport. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ "BMX Bandits' Duglas T Stewart: 'I create beauty out of pain and ugliness'". the Guardian. 26 January 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

External links

edit- 2001 Settlement Population - Census data

- What's On In Motherwell