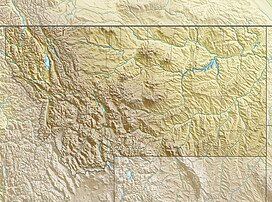

The Beartooth Mountains are located in south central Montana and northwest Wyoming, U.S. and are part of the 944,000 acres (382,000 ha) Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, within Custer, Gallatin and Shoshone National Forests. The Beartooths are the location of Granite Peak, which at 12,807 feet (3,904 m) is the highest point in the state of Montana. The mountains are just northeast of Yellowstone National Park[1] and are part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The mountains are traversed by road via the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) with the highest elevation at Beartooth Pass 10,947 ft (3,337 m)). The name of the mountain range has been attributed by the U.S. Forest Service to a rugged peak found in the range, Beartooth Peak, that has the appearance of a bear's tooth. Originally, the Beartooth Mountains were named after Beartooth Butte, a large block of paleozoic sediments on the Beartooth Plateau, and Beartooth Butte was named for a tooth-like structure that projects from the front of the butte.

| Beartooth Mountains | |

|---|---|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Granite Peak |

| Elevation | 12,799 ft (3,901 m) |

| Coordinates | 45°09′48″N 109°48′26″W / 45.16333°N 109.80722°W |

| Geography | |

| Country | United States |

| States |

|

| Parent range | Rocky Mountains |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Laramide |

The Beartooth Mountains sit upon the larger Beartooth Plateau.

History

editThe remoteness of the region contributed to its obscurity until the 1870s. The Crow tribe of Native Americans used the valleys of the mountains for hunting game animals and for winter shelter from the harsh winds of the plains. Though trappers entered the region in the 1830s, formal exploration by the U.S. Government did not occur until 1878. While gold had been discovered earlier in the mountain range, the major expansion of mining began in 1882. Expansion continued adding more infrastructure for the mines. As growth continued there were six companies that had stakes in the New World Mining District. Between 1900-1955 the district has produced over 65,000 ozt (2,000 kg) of gold, 500,000 ozt (16,000 kg) of silver, and amounts of copper, zinc, and lead ore. One of the main limiting factors was the remoteness. Over time many of the mines ceased operations due to lack of funds or collapses that were not financially viable to correct. In 1989 Crown Butte Mines proposed massive additions to operations in the area. Once they began preparations for starting new mining operations, they came under public scrutiny based on the proximity to Yellowstone National Park and public fears that waste would find its way into the park. In 1996 the federal government paid Crown Butte Mines $65 million to defray costs they had already paid; they had to pay $22.5 million to help repair the damage done to the surrounding environment.[2]

The Beartooth Mountains have been considered for inclusion in the national park system. In 1939, the director of the National Park Service drafted a presidential proclamation outlining the boundaries of a "Beartooth National Monument," but President Franklin D. Roosevelt never signed it. During the summer of 1960, The Wilderness Society organized an expedition into the Beartooths for Forest Service and National Park Service officials. Members of the expedition debated whether the mountains ought to be a wilderness area or a national park, but they reached no consensus and never made a formal proposal. Environmental advocates continued to push for the area's preservation in order to defend the northern borders of Yellowstone National Park from development. Finally, in 1975 the Beartooths were protected as part of the Absaroka–Beartooth Wilderness.[3]

Ecology

editThe ecosystem of the Beartooth Mountains is one of the most unique in the Contiguous United States partly due to being part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. This space allows a great diversity with 34,375 square miles (89,030 km2) of nearly intact wilderness. With the protection to the terrestrial habitats all of the bodies of water are classified as Outstanding National Resource Waters, giving them the highest protections under the Clean Water Act. The cleanliness of the bodies of water led them to be used as a benchmark to compare others in the northern Rocky Mountains. Most of the current species are currently protected.

Fauna

editThe mountains are home to many of North America's largest animals, including one of the few grizzly bear populations in the contiguous United States. There are rare sightings of lynx and wolverines and a population of cougars and recently reintroduced wolves. There are some of the largest herds of bison and elk in North America.

Flora

editThe Beartooth Mountains also have a very diverse range of trees, mostly conifers with stands of aspen and cottonwoods. The conifers mainly consist of Engelmann spruce, subalpine fir, whitebark pine, and lodgepole pine below 9,000 ft (2,700 m). Above 9,000 ft (2,700 m) there are few trees, the flora including grasses, wildflowers, and sagebrush.[4][5]

Geology

editThe Beartooth mountains are composed of Precambrian granite and crystalline metamorphic rocks dated at approximately 2.7 to 4 billion years old, making these rocks among the oldest on Earth. The Stillwater igneous complex within the mountains is the location of the largest known deposits of platinum and chromium and the second largest deposits of nickel found in the United States. Older ages (4-3.2 billion years) are found in zircon crystals in meta-sedimentary rocks. The most abundant rocks in the Beartooths (gneiss, amphibolites and granites, as well as the Stillwater Complex) are 2.9-2.7 billion years old.[6]

IUGS geological heritage site

editIn respect of their 'record of early crustal genesis and evolution', the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) included the 'Archean Rocks of the Eastern Beartooth Mountains' in its assemblage of 100 'geological heritage sites' around the world in a listing published in October 2022. The organisation defines an IUGS Geological Heritage Site as 'a key place with geological elements and/or processes of international scientific relevance, used as a reference, and/or with a substantial contribution to the development of geological sciences through history.'[7]

Elevation and peaks

editHuge expansive plateaus are found at altitudes in excess of 10,000 ft (3,000 m) with over 25 peaks exceeding 12,000 ft (3,700 m). The mountains have over 300 pristine lakes and some waterfalls in excess of 300 ft (100 m). Winters are severe with heavy snow and incessant winds. Approximately 25 small glaciers exist in the Beartooths with Grasshopper Glacier being one of the more distinctive.

The highest peaks of the Beartooth Mountains are clustered in three groups, topped by Granite Peak, Mount Wood 12,649 ft (3,855 m), and Castle Mountain 12,617 ft (3,846 m). The cluster containing Mount Wood is named the Granite Range.[8] The largest of these three contiguous areas above 10,000 ft (3,000 m), which extends into Wyoming, is the one dominated by Castle Mountain.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Detail". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ "Abandoned Mines". Montana DEQ. Montana DEQ. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Dilsaver, Lary M.; Wyckoff, William (Autumn 2009). "Failed National Parks in the Last Best Place". Montana The Magazine of Western History. 59 (3): 18. JSTOR 40543651. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Plants". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ "report_vt_4cbl" (PDF). U.S. National Park Service.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2017-06-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The First 100 IUGS Geological Heritage Sites" (PDF). IUGS International Commission on Geoheritage. IUGS. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Reese, Rick (1985). Montana Mountain Ranges; Number One, Rev. Ed. Helena, Montana: Montana Magazine. p. 91. ISBN 0-938314-17-3.

External links

edit- U.S. Forest Service. "Beartooth Ranger District". Custer National Forest. Archived from the original on 25 July 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-11.

- Wilderness.net. "Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness". The National Wilderness Preservation System. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2006-07-11.