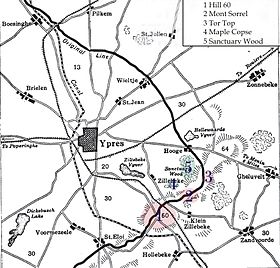

In World War I, the area around Hooge on Bellewaerde Ridge, about 2.5 mi (4 km) east of Ypres in Flanders in Belgium, was one of the easternmost sectors of the Ypres Salient and was the site of much fighting between German and Allied forces.

Within a 0.62 mi (1 km) radius of Hooge are the sites of Château Wood, Sanctuary Wood, Railway Wood and Menin Road. There are four Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) war cemeteries in this area and several museums and memorials. Hill 62 and Mount Sorrel (Also Mont Sorrel) are further south, while the sites known to British and Commonwealth soldiers as Stirling Castle and Clapham Junction are further east.

Background

editHooge

editFor much of the war, Hooge was one of the easternmost sectors of the Ypres Salient, being almost constantly exposed to enemy attacks from three sides. After the First Battle of Ypres in 1914, the front line of the salient ran through the Hooge area and there was almost constant fighting in the region over the next three years, during which Hooge and the Château de Hooge, a local manor house were destroyed.[1] Around the village, the opposing front lines were almost within whispering distance of each other. With its ruined village and a maze of battered and confusing trench lines, the area was regarded as a hazardous area for the infantry, where snipers abounded and trench raids were frequent. Both sides saw Hooge as a particularly important area and a key target for heavy artillery bombardment.[2]

Geography of the Ypres Salient

editYpres is overlooked by Kemmel Hill in the south-west and from the east by low hills running south-west to north-east with Wytschaete (Wijtschate), Hill 60 to the east of Verbrandenmolen, Hooge, Polygon Wood and Passchendaele (Passendale). The high point of the ridge is at Wytschaete, 7,000 yd (6,400 m) from Ypres, while at Hollebeke the ridge is 4,000 yd (3,700 m) distant and recedes to 7,000 yd (6,400 m) at Polygon Wood. Wytschaete is about 150 ft (46 m) above the plain; on the Ypres–Menin road at Hooge, the elevation is about 100 ft (30 m) and 70 ft (21 m) at Passchendaele. The rises are slight apart from the vicinity of Zonnebeke which has a gradient of 1:33. From Hooge and to the east, the slope is 1:60 and near Hollebeke, it is 1:75; the heights are subtle and resemble a saucer lip around the city. The main ridge has spurs sloping east and one is particularly noticeable at Wytschaete, which runs 2 mi (3.2 km) south-east to Messines (Mesen) with a gentle slope to the east and a 1:10 decline to the west. Further south is the muddy valley of the Douve river, Ploegsteert Wood (Plugstreet to the British) and Hill 63. West of Messines Ridge is the parallel Wulverghem (Spanbroekmolen) Spur and the Oosttaverne Spur, also parallel, lies further east. The general aspect south and east of Ypres is one of low ridges and dips, gradually flattening northwards beyond Passchendaele into a featureless plain.[3]

Possession of the higher ground to the south and east of Ypres gives ample scope for ground observation, enfilade fire and converging artillery bombardments. An occupier also has the advantage that artillery deployments and the movement of reinforcements, supplies and stores can be screened from view. The ridge had woods from Wytschaete to Zonnebeke giving good cover, some being of notable size like Polygon Wood and those later named Battle Wood, Shrewsbury Forest and Sanctuary Wood. In 1914, the woods usually had undergrowth but by 1917, artillery bombardments had reduced the woods to tree stumps, shattered tree trunks and barbed wire tangled on the ground and shell-holes; the fields in gaps between the woods were 800–1,000 yd (730–910 m) wide and devoid of cover. Roads in this area were usually unpaved, except for the main ones from Ypres, with occasional villages and houses. The lowland west of the ridge was a mixture of meadow and fields, with high hedgerows dotted with trees, cut by streams and ditches emptying into canals. The main road to Ypres from Poperinge to Vlamertinge is in a defile, easily observed from the ridge.[4]

Military operations

edit1914

editFirst Battle of Ypres

editDuring the First Battle of Ypres (19 October – 22 November 1914), the Franco-British captured the town of Ypres from the Germans, the Château de Hooge was used by the commanders of the 1st Division and 2nd Division for a joint divisional headquarters. When the château was shelled by German forces on 31 October 1914, the divisional commanders Major General S. H. Lomax and Major-General Charles Monro were injured, as were several members of their staffs, and some British soldiers were killed and Lomax died of his wounds several months later.[1] By the end of the battle in November 1914 the Germans had been driven back but the front line of the Ypres Salient ran around Hooge.[5]

1915

editMilitary mining

editFrom the spring of 1915, there was constant underground fighting in the Ypres Salient at Hooge, Hill 60, Railway Wood, Sanctuary Wood, St Eloi and The Bluff which required the deployment of new drafts of tunnellers for several months after the formation of the first eight tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers.[6] On 21 February 1915, the Germans exploded the first mine beneath the trenches at Hooge.[7]

Second Battle of Ypres

editThe British were forced to retreat from Zonnebeke, Veldhoek and the St Julien arc from 5–6 May 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April – 25 May 1915) to a surveyed and prepared position closer to Ypres. From 24 to 25 May 1915, the Battle of Bellewaarde was fought in the area until the end of the German offensive.[2] During the night of 25/26 May reserve troops dug a new trench from the Menin road to Zouave Wood. The Cavalry Corps reoccupied Hooge and the chateau and further north the line was pushed forward and consolidated. The front line was straight from Kemmel to Hooge Chateau then curved back to the north-west of Zouave Wood then north again to Railway Wood, Hooge being at the angle of a pronounced salient.[8][9]

Raid on Hooge Chateau

editOn 2 June 1915, German artillery bombarded the Hooge area from 5:00 a.m. to noon leaving only two walls of the chateau standing, after which infantry attacked and captured the chateau and stables. A counter-attack on the night of 3/4 June recovered the stables but the Germans held onto the chateau.[10]

Actions of Hooge

editOn 19 July, the Germans held Hooge Chateau and the British the stables and no man's land either side was 70–150 yd (64–137 m). Inside the German salient was a fortification under which the 175th Tunnelling Company had dug a gallery 190 ft (58 m) long and charged a mine with 3,500 lb (1,600 kg) of Ammonal but waterlogged ground required the explosives to be loaded upwards. The mine was sprung at 7:00 p.m. and left a crater 120 ft (37 m) wide and 20 ft (6.1 m) which was rushed by two companied of the 8th Brigade, 3rd Division. No artillery-fire had been opened before the attack and the Germans were surprised as bombers of the 8th Brigade advanced 300 yd (270 m) but then had to retire 200 yd (180 m) when they ran out of bombs. The trenches near the crater were consolidated and connected to the old front line, the 8th Brigade losing 75 casualties and taking 20 prisoners. On 22 July, the 3rd Division attacked east of the new line during the evening and the 14th (Light) Division attacked further north at Railway Wood but lacking surprise, both attacks failed.[11]

On 30 July the Germans attacked Hooge against the front of the 14th Division, which had held the line for a week. The area had been suspiciously quiet the night before and at 3:15 a.m. the site of the stables exploded and jets of fire covered the front trenches, the first German flame thrower attack against British troops. A simultaneous bombardment began, most of the 8th Rifle Brigade was overrun and the rest retreated to the support line. A second attempt to use the flame throwers was frustrated by rapid fire but attempts to counter-attack failed and most of the captured trenches were consolidated by the Germans.[12] On 6 August, the 6th Division relieved the 14th Division and made a deliberate attack, with diversions on either flank by the 49th Division near Boesinghe, the 46th Division near Hill 60 and the 17th Division further right along with the 28th Division. From 3 August heavy artillery bombardments were fired at different times during the early hours. French artillery and 3 Squadron RFC participated and two brigades attacked after a hurricane bombardment. The brigades linked at the crater and dug in and German counter-attacks were broken up by the artillery which with direction by artillery-observation aircraft suppressed German artillery retaliation until mid-morning, when visibility reduced. Part of the captured ground on the right was evacuated under intense bombardment during the night. The 16th Brigade had 833 losses and the 18th Brigade 1,295 casualties, mostly from artillery fire after the attack.[13]

1916

editBattle of Mont Sorrel

editOn 3 June 1916, the northern flank of the German attack at Mont Sorrel, Reserve Infantry Regiment 22 attacked towards Hooge but was repulsed. The Canadians were reinforced, defeated three night attacks before retiring before dawn to avoid being overrun. On 6 June the Germans sprung four mines under the front line at Hooge and captured the support trenches and remnants of the front trenches on the right. A counter-attack was considered but priority was given to the attacks due further south and the reserve line converted to be the new front line to avoid the costly occupation of such exposed ground.[14]

1917

editThird Battle of Ypres

editA raid by the 8th Division in II Corps, was made on Hooge on the night of 10/11 July, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Roland Haig. The raiders assembled so close to the barrage that several soldiers were wounded and then a machine-gun caused more casualties. The German resistance was so determined that only one prisoner was lifted and after 44 minutes the raiders retired, claiming 70–80 Germans killed for 36 casualties. On 31 July, the first day of the Battle of Pilckem Ridge, the 8th Division advanced towards Westhoek and the 24th Brigade advanced through Hooge, over the Menin road and took its objectives relatively easily. The southern flank then became exposed to the concentrated fire of German machine-guns from Nonne Boschen and Glencorse Wood in the area to be taken by the 30th Division.[15]

1918

editBattle of the Lys

editThe Germans retook Hooge in April 1918 as part of the Spring Offensive but were driven back from the area by the British on 28 September[16] as the offensive faltered.

Underground warfare

edit1915

editAfter the Second Battle of Ypres and the Battle of Bellewaarde (24–25 May), local operations continued around Hooge. In the Château grounds a captured British strongpoint was subjected to a mining attack by the 175th Tunnelling Company. In June 1915,

There is some urgent [mining] work to be done at once in a village [Hooge] on a main road east of Ypres. We hold one half and the job is to get the G[ermans] out of the other, failing that they may get us out and so obtain another hilltop from which to overlook the land. It is a significant fact that all their recent attacks round Ypres have been directed on hill tops and have rested content on the same, without trying really hard to advance down the slopes towards us.

— Cowan[2]

The tunnellers dug a gallery about 190 ft (58 m) long under the German position and placed a 3,500 lb (1,600 kg) charge. As Hooge was on the apex of the Ypres Salient, it was considered a most dangerous job and the British command initially relied on volunteers.[2] The 175th Tunnelling Company commander wrote,

[Hooge] was a small village in ruins on top of the ridge, Hooge meaning height, astride the Menin Road. On the north side of the road was a chateau with a separate annex standing in its own grounds by a large wood. Behind the chateau was Bellewarde Lake. In front of the chateau and east of the village proper were the racing stables (...). The stables were at the very apex of the salient. They were actually in our front line. The trenches were shallow and primitive, even the front line ones, and to reach the front lines some tunnels had been driven under the road and part of the ruins. No Man's Land between us and the Germans was littered with blackened corpses (...) and the stink was abominable. (...) Our objective was to sink a shaft, then tunnel under the chateau and annex and blow them up.

— Cowan[2]

The work was completed in five and a half weeks. The first attempt at tunnelling started in a stable and failed because the soil was too sandy. A second shaft was sunk from the ruins of a gardener's cottage nearby. The main tunnel was in the end 190 ft (58 m) long, with a branch off this after about 70 ft (21 m), this second tunnel running a further 100 ft (30 m) on. The intention was to blow two charges under the German concrete fortifications, although the smaller tunnel was found to be off course. The explosive—used for the first time by the British—was ammonal supported by gunpowder and guncotton, making the Hooge mine the largest mine of the war thus far built. The main difficulties for the tunnellers were that the water table is very high, and that the clay expands as soon as it comes into contact with the air.[17]

At 7:00 p.m. on 19 July 1915, the mine was fired. The explosion created a hole some 6.6 yd (6 m) deep and almost 44 yd (40 m) wide.[17] The far side of the crater was then taken and secured by men from the 1st Battalion, Gordon Highlanders and 4th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment. Ten of the latter were killed by debris from the mine as they waited in advanced positions.[18] The Germans tried to recover their lost position but were driven back by the British infantry and a heavy artillery bombardment.[17] The mine fired by 175th Tunnelling Company at Hooge on 19 July 1915 was only the second British offensive underground attack in the Ypres Salient. On 17 April 1915, 173rd Tunnelling Company had blown five mines at Hill 60 using gunpowder and guncotton but none of these mines were even half as powerful as the Hooge charge. While the mine enabled the British infantry to take Hooge, the Germans soon took back all and more of the ground they had lost.[2] By 30 July the German units had managed to take control of the château and the surrounding area.[19]

When 177th Tunnelling Company arrived at Hooge in November 1915, underground warfare in the area was far from over.[2] One of the busiest areas for the miners on both sides was Railway Wood, an area at Hooge where the old Ypres–Roeselare railway crossed the Ypres–Menen road. Aerial photographs clearly show the proliferation of mine warfare in the Railway Wood sector during the unit's presence there, with craters lying almost exclusively in no man's land between the British and German trenches.[20] With both sides trying to undermine their enemy, much of the unit's activity at Railway Wood consisted of creating and maintaining a shallow fighting system with camouflets, a deeper defensive system as well as offensive galleries from an underground shaft.[21]

1916

editOn the morning of 28 April 1916, a German camouflet killed three men of 177th Tunnelling Company, including an officer (Lieutenant C.G. Boothby). The men were trapped underground and their bodies not recovered. After the war, they were commemorated nearby at the RE Grave, Railway Wood. On 6 June 1916, the Experimental Company of the Prussian Guard Pioneers succeeded in blowing four large mines under the British trenches at Hooge held by the 28th Canadian Battalion.[22] After intense and sustained fighting, the Germans also retook the crater created by the British mine on 19 July 1915 as well as the British front line.[23] The German surprise offensive also captured the neighbouring Observatory Ridge and Sanctuary Wood—the only high ground on British hands in the whole of the Ypres Salient. Canadian units later regained Observatory Ridge and Sanctuary Wood, but not Hooge.[2]

1917

editWhile engaged at Hooge until August 1917, the 177th Tunnelling Company also built a forward accommodation scheme in the Cambridge Road sector along the rear edge of Railway Wood, halfway in between Wieltje and Hooge. The Cambridge Road dugout system was located within 100 metres (110 yd) of the front line. It was connected to the mining scheme beneath Railway Wood and eventually became one of the most complex underground shelter systems in the Ypres Salient. Its mined galleries were named after London streets for easy orientation.[24]

177th Tunnelling Company was involved in constructing new dugouts beneath the Menin Road in the centre of Hooge, located in between 175th TC's July 1915 mine crater and the stables of the destroyed Château de Hooge.[25] Parts of these dugouts now lie beneath the Hooge Crater CWGC Cemetery opposite the "Hooge Crater Museum". Further projects of the 177th Tunnelling Company in the area were the Birr Cross Roads dugout and dressing station beneath the Menin Road further west of Hooge,[26] and the Canal Dugouts along the Ieperlee.[27] Fighting in the Hooge sector continued until 1918, with the craters (tactically important in relatively flat countryside) frequently changing sides.[19]

Commemoration

editHooge and Bellewaarde

editAmong those killed in the fighting in Hooge was Gerard Anderson, the British hurdler who participated in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics and died in November 1914.[28][29]

Although the crater created in Hooge by the British mine on 19 July 1915 was filled in after the war as untenable and the repository of hundreds of bodies, several other large mine craters that were created over the course of the fighting can still be seen.[30] The most visible evidence remaining today is a large pond near the hotel and restaurant at the Bellewaerde theme park. The site is the result of work overseen by Baron de Wynck, who landscaped three mine craters (blown by German units in June 1916 as part of their offensive against Canadian troops) into the existing pond near the hotel (image Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine). Further craters can be found in and around Hooge, Bellewaerde Ridge and Railway Wood.

The "Hooge Crater Museum", founded in 1994, is opposite Hooge Crater CWGC.[31] To the west of Hooge is the "Menin Road Museum".

- Hooge Crater Cemetery: Hooge became the location for a war cemetery in October 1917.[31] buried here is Patrick Bugden VC (1897–1917), killed during the Battle of Polygon Wood.[32]

- Memorial to the King's Royal Rifle Corps, Hooge

- Birr Cross Roads Cemetery is located along the Menin Road, just west of Hooge. There are now 833 Commonwealth soldiers buried or commemorated here, of which 334 are unidentified.[33]

- Memorial to Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, Westhoek

Railway Wood

edit- Liverpool Scottish Memorial, Railway Wood

- RE Grave, Railway Wood: A short distance north-west of Hooge. The memorial marks the spot where twelve soldiers (eight Royal Engineers of the 177th Tunnelling Company and four attached infantrymen) were killed between November 1915 and August 1917 while tunnelling under the hill near Hooge during the defence of Ypres; their bodies were not recovered.[34][35] One of the twelve men commemorated here is Second Lieutenant Charles Geoffrey Boothby (1894–1916), whose wartime letters to his girlfriend were published in 2005.[36]

Sanctuary Wood

editExtensive woodlands, known locally as 'Drieblotenbos Hoge Netelaar' but called 'Sanctuary Wood' by British soldiers who took refuge here in November 1914.

- Sanctuary Wood Cemetery

- Sanctuary Wood Museum Hill 62

- Memorial to Lieutenant Keith Rae

- Canadian Hill 62 (Sanctuary Wood) Memorial, located beside Sanctuary Wood on the top of Mount Sorrel, which lies next to Hill 62. All of these are locations the Canadians held or recaptured from the Germans during the offensive operations in early June 1916.

Gallery

edit-

View of Hooge from the south, with Hooge Crater Cemetery clearly visible

-

Hooge Crater Cemetery entrance with Cross of Sacrifice and the stone-faced circle designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens in memory of the many craters nearby

-

Mine crater at Railway Wood near Hooge, located just behind the Royal Engineers' Grave

-

RE Grave, Railway Wood, a memorial to men of the 177th Tunnelling Company

Footnotes

edit- ^ a b Edmonds 1925, pp. 323–324.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barton 2004, pp. 148–154.

- ^ Edmonds 1925, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Edmonds 1925, pp. 129–131.

- ^ Edmonds 1925, pp. 414–417.

- ^ Barton 2004, p. 165.

- ^ Edmonds & Wynne 1995, p. 29.

- ^ Edmonds & Wynne 1995, p. 353.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, p. 97.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, pp. 106–109.

- ^ Edmonds 1993, pp. 234, 239.

- ^ Bax & Boraston 2001, pp. 124, 128–130.

- ^ Commonwealth War Graves Commission, undated, accessed 16 February 2007

- ^ a b c http://www.webmatters.net/belgium/ww1_hooge.htm access date 24 April 2015

- ^ Hooge on ww1battlefields.co.uk, accessed 25 April 2015

- ^ a b Battlefields 14-18, undated, accessed 16 February 2007

- ^ Barton 2004, p. 123.

- ^ Barton 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Jones 2010, p. 139.

- ^ With the British Army in Flanders: Hooge Crater, access date 26 April 2015.

- ^ Barton 2004, pp. 216–218.

- ^ Barton 2004, p. 150.

- ^ Barton 2004, p. 262.

- ^ Barton 2004, p. 228.

- ^ ANDERSON, GERARD RUPERT LAURIE. Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

- ^ "England losing athletes; Many Prominent in Sporting Circles Die on Battle Fields" (PDF). New York Times. 1 December 1914.

- ^ WWI Battlefields, undated, accessed 16 February 2007

- ^ a b firstworldwar.com Hooge Museum

- ^ Bean 1941, p. 815.

- ^ CWGC Cemetery Details: Birr Cross Roads Cemetery

- ^ www.wo1.be accessed 19 June 2006

- ^ wo1.be Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 19 June 2006

- ^ Stockwin 2005.

References

edit- Barton, Peter; et al. (2004). Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers' War 1914−1918. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-237-8.

- Bax, C. E. O.; Boraston, J. H. (2001) [1926]. Eighth Division in War 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Medici Society. ISBN 978-1-897632-67-3.

- Bean, C. E. W. (1941) [1933]. The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. IV (1941 ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 978-0-7022-1710-4. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II. London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (1995) [1927]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Winter 1914–15 Battle of Neuve Chapelle: Battles of Ypres. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press repr. ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-218-0.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1928). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Battles of Aubers Ridge, Festubert, and Loos. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents By Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962526.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914–1918. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Stockwin, A., ed. (2005). Thirty-odd Feet below Belgium: An Affair of Letters in the Great War 1915–1916. Tunbridge Wells: Parapress. ISBN 978-1-898594-80-2.

Further reading

edit- Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty-one Divisions of the German Army which Participated in the War (1914–1918). Document (United States. War Department). number 905. Washington D.C.: United States Army, American Expeditionary Forces, Intelligence Section. 1920. OCLC 565067054. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Marden, T. O. (2008) [1920]. A Short History of the 6th Division August 1914 – March 1919 (repr. BiblioBazaar ed.). London: Hugh Rees. OCLC 565246610. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1962). Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. pp. 152–154. OCLC 557523890. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Wyrall, E. (2002) [1921]. The History of the Second Division, 1914–1918. Vol. I (repr. Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Thomas Nelson and Sons. ISBN 978-1-84342-207-5. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Willson, B. (1916). In the Ypres Salient: The Story of a Fortnight's Canadian Fighting, 2–16 June 1916 (online ed.). London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. OCLC 4142910. Retrieved 25 November 2016.