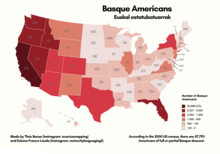

Basque Americans (Basque: Euskal estatubatuarrak, Spanish: Vasco estadounidenses) are Americans of Basque descent. According to the 2000 US census, there are 57,793 Americans of full or partial Basque descent.

| |

| Total population | |

| 56,297[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| California, Idaho, Nevada, Washington, Oregon, Utah | |

| Languages | |

| American English, Basque, Spanish, French | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Basque people and other groups of the Basque diaspora |

Ties to early American history

editReferring to the historical ties that existed between the Basque Country and the United States, some authors stress the admiration felt by John Adams, second president of the U.S., for the Basques' historical form of government. Adams, who on his tour of Europe visited Biscay, was impressed. He cited the Basques as an example in A defense of the Constitution of the United States, as he wrote in 1786:

"In a research like this, after those people in Europe who have had the skill, courage, and fortune, to preserve a voice in the government, Biscay, in Spain, ought by no means to be omitted. While their neighbours have long since resigned all their pretensions into the hands of kings and priests, this extraordinary people have preserved their ancient language, genius, laws, government, and manners, without innovation, longer than any other nation of Europe. Of Celtic extraction, they once inhabited some of the finest parts of the ancient Boetica; but their love of liberty, and unconquerable aversion to a foreign servitude, made them retire, when invaded and overpowered in their ancient feats, into these mountainous countries, called by the ancients Cantabria..."

"...It is a republic; and one of the privileges they have most insisted on, is not to have a king: another was, that every new lord, at his accession, should come into the country in person, with one of his legs bare, and take an oath to preserve the privileges of the lordship".[2]

Authors such as Navascues, and the Basque-American Pete T. Cenarrusa, former Secretary of the State of Idaho, agree in stressing the influence of the Foruak or Charters of Biscay [Code of Laws in Biscay] on some parts of the U.S. Constitution. John Adams traveled in 1779 to Europe to study and compare the various forms of government then found on the Old Continent. The American Constitution was approved by the first thirteen states on 17 September 1787.

Migration and sheepherding

editBasque immigration peaked after the Spanish Carlist Wars in the 1830s—Ebro customs relocated to the Pyrenees—and in the 1860s following the discovery of gold in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range of California. The current day descendants of Basque immigrants remain most notably in this area and across the Sierras into the neighboring area of northern Nevada, then northward, into Idaho. When the present-day states of California, Arizona and New Mexico were annexed by the United States after the Mexican–American War (1848), there were reportedly thousands of Basques of Spanish or mixed Mexican origin living in the Pacific Northwest.

By the 1850s, there were some Basque sheepherders working in Cahuenga Valley (today Los Angeles, California). In the 1870s, the Los Angeles and Inland Empire land rush reportedly attracted thousands of Basques from Spain, Mexico and Latin America, but such reports do not bear out in a current census of Basque persons in the Southern United States, where Basque persons are exceptionally rare in U.S. census reporting. By the 1880s, Basque immigration had spread up into Oregon, Utah, Montana and Wyoming, with significantly lesser numbers reaching the states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas in the southernmost region. By 1895, there were reportedly about ten thousand self-reporting Basque-Americans in the United States.

Basques who migrated to the United States versus South America faced a language barrier that took years and in some cases generations to overcome, which disadvantaged them, while Basques migrating to South America ended up having better outcomes more immediately.[3]

The current census figures demonstrated in the U.S. map on this page are remarkably low in comparison to these reports and the overall increase in the U.S. population since the 19th century. There has been a radical decrease in Basque immigration since that era, which has resulted in a significant decline in persons of Basque national or Spanish origin throughout the United States. Most of the self-reporting Basque persons remaining in the U.S. today are descendants of the original peak of Basque immigrants, who arrived between 200 and 100 years ago, typically reporting as multi-generational or great-great-grandchildren (1860 immigrants) as opposed to native-born persons of Basque ethnic identification and their subsequent immediate family, children, or grandchildren.

The degree to which one self-reports being "Basque" is a personal choice, often tied to an interest in one's heritage, whether one is the grandchild of a native-born Basque or of significantly mixed Native American (Mexican, South American, etc.), white European, or other racial admixture. There are significant numbers of Mexicans with Basque names, as many as one million self-reporting Mexicans of Basque racial or surname heritage today.

Thousands of Basques were recruited from Spain due to severe labor shortages during World War II. They came under contract with the Western Range Association between the 1940s until around 1970.[4] The Spanish Right of Return extends Spanish citizenship only to the grandchildren of Basque immigrants who were born in Spain and forced to flee during the Francoist uprising in the mid-1930s.

Basque clubs

editThere are nearly fifty such clubs in the United States, the oldest of which is the Central Vascoamericano (founded 1913), today New York's Euzko Etxea situated in Brooklyn. In the West, efforts were made in 1907 to set up a club in Stockton, California. In 1914, the Basque Club of Utah was founded in Ogden, while the first Zazpiak Bat Club was started in San Francisco in 1960. [5] In 1938, the Basques in the Bakersfield area founded the Kern County Basque Club. Even though, according to the most recent census, there are Basques in each of the fifty states, Basque clubs are only found in New York, Florida, California, Nevada, Idaho, Oregon, Utah, New Mexico, Colorado, Washington, Connecticut, The District of Columbia and Wyoming. However, there is a significant Basque population in Arizona, Georgia, Montana, New Jersey, and Texas.[6] Basque-American clubs have connections with other Basques around the world (across Europe, Canada, Mexico, Bolivia, Peru, Puerto Rico, Chile, Argentina, Australia, South Africa and the Philippines) to unite and consolidate a sense of identity in the global Basque diaspora.

Idahoan-Basques

editBoise is host to a community of about 3,573 Basque-Americans.[7] Prominent Basque-American elected officials in Idaho include longtime Secretary of State Pete T. Cenarrusa, his successor Ben Ysursa, both Republicans, former Boise mayor Democrat David H. Bieter, as well as Republican, J. David Navarro, the current Clerk, Auditor and Recorder of Ada County, the most populated county in Idaho. Mary Azcuenaga, an attorney who was appointed by Ronald Reagan to serve on the Federal Trade Commission, is a Basque-American born in Council, Idaho.

Basques were initially drawn to Idaho by the discovery of silver, in settlements such as Silver City. Those that did not directly become involved in mining engaged in ranching, selling beef and lamb products to the miners. While some such immigrants returned to Basque Country, many remained, later to be joined by their families following them in immigration.[8] Exact counts of Basque immigrants to Idaho are not practical to determine, as the United States Census did not distinguish between Basques from other Spanish immigrants, though a majority of Spanish immigrants to Idaho likely self-identified as Basque.[9]

Idaho achieved statehood in 1890 along with the first Basques arriving there around the same time. By 1912, some of the pioneers, such as Jose Navarro, John Achabal, Jose Bengoechea, Benito Arregui, John Echebarria, and Juan Yribar, were already settled and had property in the state.[10] Since 1990, Boise and Gernika have been sister cities.

North American Basque organizations

editIn March 1973, a group of Basque-Americans met in Reno, Nevada with a questionable proposal, especially considering Basque history. The group hoped to forge a federation and create a network within the larger Basque community of the United States. The Basques had never been united in either the Old Country nor in the New World. The Basque Country, or Euskal Herria, had never been "Zazpiak Bat" (Seven Territories Make One) representing a unified, self-conscious political community, it rather showed a political structure of a confederate nature—separate autonomous districts with a similar national, institutional and legal make-up. Euskal Herria often referred to just the local region.

This detachment of the Basques was reflected in the Basque communities of the United States. Basques of Biscayne descent in parts of Idaho and Nevada interacted little with the Basques of California, who were largely northern or "French Basques." When delegates from the Basque clubs of Los Banos, San Bernardino; and San Francisco, California; Boise and Emmett, Idaho; Elko, Ely and Reno, Nevada; Salt Lake City, Utah; and Ontario, Oregon gathered together, they were well aware that there was little if any communication between the various Basque clubs of the American West. They were attempting to cross the divide—real and imagined—between Basque-Americans. Seventeen years later "French" Basques and "Spanish" Basques joined a federation to work together. Individual clubs set aside competition in an effort to preserve and promote their shared heritage.

The North American Basque Organizations, Inc., commonly referred to by its acronym N.A.B.O., is a service organization to member clubs that does not infringe on the autonomy of each. Its prime purpose is the preservation, protection, and promotion of the historical, cultural, and social interests of Basques in the United States. NABO's function is to sponsor activities and events beyond the scope of the individual clubs, and to promote exchanges between Basque-Americans and the Basque country.

Population

editThe states with the largest Basque communities are:

- California: 17,598

- Idaho: 8,196

- Nevada: 5,056

- Oregon: 3,162

- Washington: 2,579

- Texas: 2,389

- Colorado: 2,216

- Florida: 1,653

- Utah: 1,579

- New York: 1,544

- Wyoming: 1,039

The urban areas with the largest Basque communities[7]

- Boise, ID: 3,573

- Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA: 3,432

- Reno, NV-CA: 2,216

- San Francisco-Oakland, CA: 1,930

- New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT: 1,604

- Portland, OR-WA: 1,520

- Sacramento, CA: 1,155

- Seattle, WA: 1,082

- Bakersfield, CA: 1,078

- Nampa, Idaho, ID: 1,008

- Salt Lake City-West Valley City, UT: 978

- Denver-Aurora-Lakewood, CO: 957

- Phoenix-Mesa, AZ: 904

- San Diego, CA: 872

- Miami, FL: 841

- Las Vegas-Nevada, NV: 763

- Fresno, CA: 650

- San Jose, CA: 544

The top 25 U.S. communities with population claiming Basque ancestry[11]

- Winnemucca, NV 4.2%

- Gooding, ID 4.1%

- Battle Mountain, NV 4.1%

- Elko, NV 3.7%

- Shoshone, ID 3.4%

- Cascade, ID 3.2%

- Buffalo, WY 2.6%

- Minden, NV 2.2%

- Susanville, CA 2.1%

- Hines, OR 1.8%

- Gardnerville, NV 1.7%

- Burns, OR 1.7%

- Rupert, ID 1.6%

- New Plymouth, ID 1.5%

- Vale, OR 1.4%

- Ontario, OR 1.4%

- Fallon, NV 1.3%

- Bellerose, NY 1.3%

- Caldwell, ID 1.3%

- Eagle, ID 1.2%

- Homedale, ID 1.2%

- Meridian, ID 1.2%

- Oak Park, CA 1.2%

- Palouse, WA 1.1%

- Moss Beach, CA 1.1%

Notable people

editThe following is a list of notable Basque-Americans of either full or partial Basque descent:

- Dominique Amestoy, banker, founder of Farmers and Merchants Bank

- Jeffrey Amestoy, longtime Attorney General of the State of Vermont and Chief Justice of the Vermont Supreme Court

- Rafael Anchia, member of the Texas House of Representatives

- Joe Ansolabehere, animation screenwriter and producer

- Germán Arciniegas, Writer, ambassador, college professor at Columbia University, and journalist

- David Archuleta, singer and American Idol contestant

- John Arrillaga,[12] real estate businessman, Silicon Valley

- John Ascuaga, businessman, owner of John Ascuaga's Nugget Casino Resort

- Mary Azcuenaga, former member of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

- Earl W. Bascom, painter and sculptor, father of modern rodeo

- Florence Bascom, first woman hired by United States Geological Survey

- Jose Antonio Bengoechea, Bedarona-born Idaho businessman who owned the Bengoechea Hotel

- Frank Bergon, author of four novels featuring Basque Americans[13]

- Monica Bertagnolli, oncologic surgeon and Director of the National Institutes of Health

- Dave Bieter, former Mayor of Boise, Idaho; fluent in the Basque language[14]

- Eugene W. Biscailuz, Sheriff of Los Angeles County; founder of the California Highway Patrol

- Frenchy Bordagaray, MLB player

- Pete T. Cenarrusa, former Secretary of State of Idaho

- Héctor Elizondo, film actor

- Andy Etchebarren, MLB catcher with the Baltimore Orioles, California Angels and Milwaukee Brewers[15]

- John Etchemendy,[12] former Provost of Stanford University

- John Garamendi, U.S. Congressman and former Lieutenant Governor of California

- Galen Gering, film actor

- Pete Goicoechea, Nevada State Senator and former Nevada Assemblyman

- Paul Gosar, U.S. Congressman from Arizona and former dentist

- Shayne Gostisbehere, NHL defenseman for the Philadelphia Flyers

- Jimmie Heuga, former ski racer, 1964 Olympic medalist

- Jose Iturbi, composer, conductor, and pianist

- Jim Larranaga, basketball coach

- Adam Laxalt, Attorney General of Nevada

- Paul Laxalt, former U.S. Senator and former governor of Nevada

- Robert Laxalt, writer

- Ryan Lochte, former Olympic swimmer

- Michel Moore, Chief of Police of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD)

- Ramón Músquiz (1797–1867), Governor of Texas from 1830 to 1831

- Gregorio Esparza, Tejano soldier that fought in the Battle of the Alamo and died in the Alamo with other fellow Tejanos fighting for Texas Independence.

- Joseph A. Unanue, businessman, Goya Foods

- Benny Urquidez, known as Benny the Jet, martial artist appearing in Jackie Chan films

- Ted Williams, Boston Red Sox baseball player and member of the Baseball Hall of Fame

In popular culture

editIn the 1975 Gunsmoke episode "Manolo", Robert Urich plays Manolo Etchahoun, a young man who is a member of a group of Basque immigrants who has to prove his manhood by fighting his father.

The Wyoming Basque community, including a depiction of a religious festival, is the focus of the third episode of season two of Longmire, "Death Came Like Thunder."[16]

Craig Johnson has a Basque deputy in his Walt Longmire series of books. There are frequent references to Basque culture throughout the series.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "PEOPLE REPORTING ANCESTRY. 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ "John Adams: Defence of the Constitutions: Vol. I, Letter IV". Constitution.org. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ Douglass, William A; Bilbao, Jon (2005). Amerikanuak: Basques in the New World. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 978-0-87417-675-9.[page needed]

- ^ "Las Rocosa Australian Shepherds". Lasrocosa.com. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ "Basque Club History". Basqueclub.com. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ "U.S. Basque Population".

- ^ a b "Urban Areas with Basque Communities". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-14. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ^ Totoricagüena, Gloria (2004). Boise Basques: Dreamers and Doers. Reno, NV: Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada, Reno. pp. 32–33. ISBN 1877802379. OCLC 54536757.

- ^ Mercier, Laurie; Simon-Smolinski, Carole, eds. (1990). Idaho's Ethnic Heritage: Historical Overviews. Idaho: Idaho Ethnic Heritage Project. p. 17. OCLC 23178138.

- ^ "Basque Americans in the Columbia River Basin". Washington State University, Vancouver. Archived from the original on February 12, 2007.

- ^ "Ancestry Map of Basque Communities". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on 2015-03-17. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ^ a b "Basque Studies Debut" (March/April 2007) Stanford Magazine. Retrieved 05 June 2010.

- ^ Monica Madinabeitia, "Getting to Know Frank Bergon: The Legacy of the Basque Indarra," Journal of the Society of Basque Studies in America, 28 (2008)

- ^ "Basque to the Future". Boise Weekly. May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Andy Etchebarren – Society for American Baseball Research".

- ^ "Longmire: Season 2, Episode 3 : Death Came in Like Thunder (10 June 2013)". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2015-09-20.

Further reading

edit- Douglass, William A., and Jon Bilbao, eds. Amerikanuak: Basques in the New World (U of Nevada Press, 1975).

- Douglass, William A., C. Urza, L. White and J. Zulaika, eds. The Basque Diaspora (Basque Studies Program, University of Nevada, Reno).

- Etulain, Richard W., and Jeronima Echeverria, eds. Portraits of Basques in the New World (U of Nevada Press, 1999).

- Lasagabaster, David. "Basque diaspora in the USA and language maintenance." Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 29.1 (2008): 66–90. online

- Río, David. Robert Laxalt: The Voice of the Basques in American Literature (Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada, Reno, 2007).

- Saitua, Iker. Basque Immigrants and Nevada's Sheep Industry: Geopolitics and the Making of an Agricultural Workforce, 1880–1954 (2019) excerpt

- Shostak, Elizabeth. "Basque Americans." in Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 1, Gale, 2014), pp. 251–264. online

- White, Linda, and Cameron Watson, eds. Amatxi, Amuma, Amona: Writings in Honor of Basque Women (Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada, 2003).

- Zubiri, Nancy. A Travel Guide to Basque America: Families, Feasts, and Festivals (2nd ed. U of Nevada Press, 2006).

External links

edit- Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada, Reno

- (Amerketako euskaldunei buruzko webgunea)

- Buber's Basque Page

- Epodunk, Basque Ancestry Map of the United States

- Kaletarrak eta Baserritarrak: East Coast and West Coast Basques in the United States by Gloria P. Totoricagüena.

- Interstitial Culture, Virtual Ethnicity, and Hyphenated Basque Identity in the New Millennium by William A. Douglass.

- Euroamericans.net: The Basque in America

- U.S. Census

- Basque Library, University of Nevada, Reno

- Basque Digital Collection University of Nevada, Reno Libraries

- Voices from Basque America University of Nevada, Reno Libraries