Hollyhock House is a house museum at Barnsdall Art Park in the East Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, United States. The house, designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright for the heiress Aline Barnsdall, is named for the hollyhocks used in its design. The main house, incorporating elements from multiple architectural styles, consists of multiple wings arranged around a central courtyard. It was built alongside two guesthouses called Residence A and B, a garage building, the Schindler Terrace, and the Spring House. Rudolph Schindler, Richard Neutra, and Wright's son Lloyd Wright helped design not only the main house but also the outbuildings. Over the years, Hollyhock House has received extensive architectural commentary. It is designated as a National Historic Landmark and is part of "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright", a World Heritage Site.

| Hollyhock House | |

|---|---|

View of Hollyhock House | |

| Location | 4800 Hollywood Boulevard, Los Angeles, California, United States |

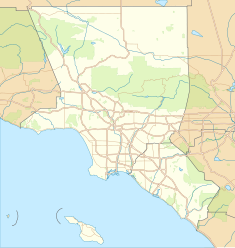

| Coordinates | 34°06′00″N 118°17′40″W / 34.10000°N 118.29444°W |

| Built | 1919–1921 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style(s) | Mayan Revival architecture |

| Governing body | Local |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2019 (43rd session) |

| Part of | The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Reference no. | 1496-004 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Official name | Aline Barnsdall Complex |

| Designated | May 6, 1971[1] |

| Reference no. | 71000143 |

| Official name | Aline Barnsdall Complex |

| Designated | April 4, 2007[2] |

| Designated | April 1, 1963[3] |

| Reference no. | 12 |

Barnsdall had wanted to build a theatrical complex since 1915, and she acquired the site, then known as Olive Hill, in 1919. She hired Wright to design the complex, plans for which were revised multiple times. The house and its outbuildings, completed in 1921, were the only parts of the theatrical complex to be built. The Los Angeles city government acquired Hollyhock House and some of the surrounding land in 1927, establishing Barnsdall Park and leasing the main house to the California Art Club for 15 years. Barnsdall retained one of the guesthouses until her death. Dorothy Clune Murray leased the main house in 1946 and began renovating it. The city government added a temporary art-gallery wing in the 1950s. Further renovations to the main house took place in the 1970s and the early 21st century.

The exterior walls are made of hollow clay tiles, wood frames, and stucco, sloping inward at their tops. The house is accessed by a long loggia and is surrounded by various terraces, with pools to its east and west. The house has 6,000 square feet (560 m2) of interior space, with a U-shaped plan. The rooms are spread across three sections: the living and music room wing to the west, the dining and kitchen wing to the north, and the gallery and bedroom wing to the south. The outbuildings are constructed of similar materials to the main house. The Barnsdall Art Park Foundation and the Friends of Hollyhock House help manage the house and its activities.

Site

editHollyhock House is located on the northern slope of Olive Hill, a knoll within Barnsdall Art Park in the East Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, United States.[4] The house is at 4800 Hollywood Boulevard,[5] between Vermont Avenue to the east and Edgemont Street to the west.[6][7] The hill rises 490 feet (150 m) above sea level and 100 feet (30 m) above the street.[8][9] The designs of several other buildings in the park, including a gallery, theater, and junior arts center, are inspired by that of Hollyhock House.[10] Other structures, including apartments, stores, and a hospital, have been built around the house on three sides.[11] The Vermont/Sunset station, served by Los Angeles Metro Rail's B Line, is southeast of the house.[12]

Hollyhock House and Barnsdall Art Park were part of the estate of the heiress Aline Barnsdall,[13] which measured 1,231 feet (375 m) wide from north to south and 1,255 feet (383 m) wide from west to east.[7] The site was part of Rancho Los Feliz, a Spanish-era land grant given to José Vicente Feliz in 1802; the house's site was then acquired by James Lick in 1873 and subsequently subdivided.[14] Before Barnsdall had acquired Olive Hill in 1919, there were low-rise stores and bungalows to the north.[15] The hill itself was undeveloped and had contained olive trees since the 1890s,[15][8] back when the site belonged to J. H. Spires.[9] Despite being close to streetcar routes, Olive Hill was not appealing to developers because it was not near either Downtown Los Angeles or central Hollywood.[15] The hill had hosted Easter services for years before Barnsdall's acquisition of the site.[8][15] At the time of Barnsdall's purchase, the olive trees were planted 18 to 20 feet (5.5 to 6.1 m) apart on a grid, and the hill was accessed by two roads from the southeast and northeast.[7]

Development

editHollyhock House's developer, Aline Barnsdall, was an oil heiress from Pennsylvania[16][17] who had wanted to develop an arts and live-theater complex.[18][19] In the early 1910s, Barnsdall traveled to Chicago to become a theatrical producer.[17][20] She first met Wright in Chicago no later than early 1915, when she hired him to design a building for the Chicago Little Theatre.[21][20] After vacationing in California, she decided to erect the theatrical building there instead;[21][22] she wrote in early 1916 that she was searching for a site.[23][24] Barnsdall originally wanted to build the theater in San Francisco,[22] but she had changed her plans once more by early 1918, when she decided to construct a theatrical complex in Southern California. Barnsdall decided to hire Wright, with whom she had been in sporadic contact.[25] In 1917, Barnsdall's father died and left her a large bequest, and Barnsdall also began planning a house for herself and her newborn daughter Betty.[25][26]

Initial plans

editWright began drawing up conceptual plans for the house and theater in 1916,[14][27] working on them at his Wisconsin studio, Taliesin.[28][27] By early 1918, his plans called for a cube-shaped building with a circular auditorium containing 1,500 seats on two levels.[24] This plan, a modification of his original plan for the Chicago Little Theatre, was similar to one designed by Norman Bel Geddes, who had been Barnsdall's stage designer.[29] The house was to be designed in the Prairie style, with rooms surrounding an interior courtyard.[27] By late 1918, Wright was preparing to go to Japan, where he was designing Tokyo's Imperial Hotel. At that time, Barnsdall was looking at potential sites in Los Angeles for her house and theater.[30] Barnsdall had identified a potential site, the 36-acre (15 ha) Olive Hill tract, by mid-1919.[8][31] However, the Olive Hill site may have been discussed even before that point,[8] and Wright later told his son Lloyd that it was he who suggested that Barnsdall acquire Olive Hill.[32] In any case, Wright's office still did not have the preliminary sketches for Barnsdall's house,[31] and Wright's assistant Rudolph Schindler asked Barnsdall for the sketches.[8]

On June 3, 1919,[9] Barnsdall paid Mary Spires $300,000 for Olive Hill;[33] the tract had been for sale for several years.[15] The site was bounded by Hollywood Boulevard to the north, Edgemont Street to the west, Sunset Boulevard to the south, and Vermont Avenue to the east.[8][33][34] News media reported that Wright had been hired to design a 1,200-seat theater for more than $200,000, which would face east toward Vermont Avenue.[35][36] The theater would have had Greek-style motifs.[37] Barnsdall donated part of the site, at Sunset Boulevard and Vermont Avenue, to the Community Theatre of Hollywood.[38] She also planned a 17-room house, which was variously described as a Spanish-style structure[34] and a "modernized Aztec" style.[15][36] Barnsdall also told local media that she wanted to build houses, cottages, and apartment blocks on the site.[39] Barnsdall was supposed to have gone to Japan to discuss the theater with Wright that August,[32][40] but it is unknown whether Barnsdall actually made the trip.[32] Instead, she asked the firm of Walker & Eisen to draw up alternate plans for the residence.[34][32] Walker & Eisen proposed a five-bedroom Spanish Colonial structure costing $300,000, but Barnsdall decided not to accept these plans.[32]

Wright returned to the U.S. that September to work on Barnsdall's theater and house.[32][41] The architectural model for the theater was damaged while being shipped from Japan to the U.S., which delayed the design process.[42] Further delays occurred because both Wright and Barnsdall were separately traveling across the U.S. during late 1919.[43] Wright's drawings called for a residence on the hilltop, surrounded by various smaller structures at the bottom of the hill.[44] There would have been a theater along Vermont Avenue, an apartment complex called the Actors' Abode, and a house for her theatrical company's director.[26][45] These four buildings would cost $375,000, not much more than the estimate Walker & Eisen had given Barnsdall just for her house.[42] Wright's drawings called for the four buildings to be arranged in a pinwheel layout around the main house.[45] The main house's massing was to resemble a mesa.[46][47] There would have been an artificial stream flowing between and through the buildings,[48] similarly to Wright's later design for Fallingwater in Pennsylvania.[49][50]

Construction and modified plans

editWright could not personally supervise much of the construction, since he was simultaneously designing the Imperial Hotel,[51][52] for which he returned to Japan in December 1919.[14][53] Wright left his son Lloyd Wright in charge of the project,[54] along with Rudolph Schindler.[52][55] Although Wright offered to discuss the plans with Barnsdall in Portland, Oregon, the heiress declined the offer.[53] Lloyd selected S. G. H. Robinson as the house's general contractor;[53] Robinson estimated that the house would cost $50,000.[56] Barnsdall was anxious to have the house completed, writing to Wright in January 1920 to request that he finish the plans for the interiors.[57] Barnsdall also suggested changes to the design, and she outlined some of her requirements for the house, including the layout, the materials, and the hollyhock motif.[58] Wright later wrote that Barnsdall had come up with the house's name, Hollyhock, during his absence.[58][59]

Meanwhile, his son began soliciting bids from various contractors.[58] The plans were further revised from January to March 1920.[8][58] The revised plans called for a masonry building with hollyhock motifs and geometric Prairie-style decorations.[58] Schindler drew up plans for Residence A around the same time.[60] Construction started on April 28, 1920,[56] and Schindler began drawing up plans for the Actors Abode shortly thereafter.[56] When Wright visited the site that July, he found that work on the foundation had barely started. The same month, he sent Schindler from Taliesin to Los Angeles to oversee the house's construction.[56]

By that August, Barnsdall wanted to modify her plans for the site, since the plans for the theater had not been fully drawn out.[61] Accordingly, Barnsdall directed Wright to revise plans for the estate.[37][62] The modified plans called for an apartment house, a complex of artists' studios and shops, additional residences, and a cinema.[37][61] The apartment building replaced the Actors' Abode, and six standalone homes labeled A through F were planned for the slopes of Olive Hill.[63] In addition, some landscape features were modified.[60][63] The main residence was to be built first, with the other structures to be built later.[62][61] At that point, the main house was scheduled to be completed in December 1920, followed by the Actors' Abode, shops, and studios in May 1921 and the other buildings in October 1922.[61] Wright and Barnsdall argued over many aspects of the project, including the budget and design details,[64][51] particularly as Wright did not always design structures based on his clients' specifications.[46] According to Wright, Barnsdall would "drop suggestions as a warplane drops bombs and sails away into the blue".[65] Complicating matters, it took weeks for Wright and Barnsdall to respond to each other.[64]

Completion

editWork on Residence A was delayed by October 1920, in part because drawings for that building had not been finished.[66] Wright received a construction permit for Residence A that December, and C. D. Goldthwaite was hired as the general contractor for both residences A and B.[60] By April 1921, the art stone was still being laid, and the interior work was being delayed until the stonework was completed.[67] Goldthwaite's sluggish work delayed the project, and his poor workmanship caused the main house to leak even before its completion. Barnsdall lived in Residence A while the main house was being finished.[68] Barnsdall, disillusioned with the house's increasing costs, increasingly spent time outside of Los Angeles.[69]

Work stopped in October 1921,[69] and Wright was fired from the project due to the cost overruns.[54][70] By then, the main house and the two guesthouses were nearly finished, but the main house's second floor was incomplete.[71][72] When Wright returned from Japan in 1922, Barnsdall was thinking about selling her Olive Hill residence, and she wanted Wright to design another house in Beverly Hills.[69][73] The Condé Nast Traveler wrote that the house cost $150,000,[64] while a contemporary Los Angeles Evening Citizen News article placed the cost at $125,000.[74] Another estimate placed the final cost of the house at $200,000 and the land at $300,000.[75]

Usage

editBarnsdall ownership

editBarnsdall initially lived in Hollyhock House with her daughter Betty, their servants, and 12 dogs.[18][76] Two of Barnsdall's friends, the art collectors Louise Arensberg and Walter Conrad, moved into Residence A during 1923,[60] though it is unknown if anyone stayed there afterward.[77] Wright moved his architectural practice into Residence B the same year, remodeling that structure.[69][78] In its early years, the main house often leaked and flooded during rainstorms. Virginia Kazor, later the house's curator, said that the carpet in the living room had to be replaced multiple times.[75] Barnsdall complained about the weight of the doors, saying, "I need three men and two boys to help me get in and out of my own house!"[17][79] She rarely slept in her own bedroom[80] and reportedly preferred eating outside rather than in the dining room.[81][82] Barnsdall ultimately moved out after a year.[76]

Construction of the Little Dipper, a community theater that Wright had designed on Olive Hill, began on November 7, 1923.[62][83] A. C. Parlee was hired as the general contractor,[83] but city officials quickly ordered workers to stop construction due to building code violations.[62][84] The project was canceled when Barnsdall refused to approve further changes to the theater.[84][85] Barnsdall also considered erecting a kindergarten on her estate for Betty, though nothing came of these plans.[69][78]

As early as June 1923, Barnsdall wanted to sell the estate for up to $1.8 million.[73] That December, Barnsdall offered to donate Hollyhock House to the Los Angeles Public Library and some land to the city's Department of Recreation and Parks.[86][87] The offer included 10 acres (4.0 ha),[88][89] covering the summit of Olive Hill and the main house.[87] By then, Barnsdall no longer had any interest in developing a theater,[9][90] and she did not want the house to be used for a commercial purpose such as a hotel.[73][91] The donation included the paintings and furnishings in the living room,[92] and Wright designed some furniture for the proposed library branch as well.[78][93] In addition, the city received an option to buy the remainder of Barnsdall's estate for about $2 million.[9] The city government initially accepted the gift[94] and appointed five men to take over the home.[95] Though Barnsdall was ready to give the house's deed to the city in February 1924,[96] the city rejected the gift. Sources disagree on whether the gift was rejected because of the option's high cost[9][93] or because the terms of her gift were too restrictive.[89][97][a]

By early 1924, Parlee had sued both Barnsdall and Wright for payment; these lawsuits were eventually settled.[98] Wright also sued Barnsdall over the Japanese screens[93][98] and, at one point, sent Los Angeles County sheriffs to repossess them.[75][93] Meanwhile, Barnsdall hired Schindler to convert the Little Dipper's incomplete foundation into a public terrace, as well as decorate the second-floor bedrooms.[89] The incomplete theater's foundation became Schindler Terrace, which was finished in 1925.[62][85] Schindler added a pool and pergola next to the terrace,[62][89] and he converted the second-floor interior to a multi-room bedroom suite, as well as a closet and bathroom.[89][99] He also designed some furniture for the house.[99] Barnsdall then offered to set aside the house and surrounding land for cultural use for 50 years, provided that three cultural organizations decided to move there.[100] Subsequently, the California Art Club expressed interest in Hollyhock House,[100] and Barnsdall offered the house and land to the city again, dropping most of the restrictions.[101][102] Barnsdall stipulated that the land be used as an art and recreation center.[102]

Institutional use

editLate 1920s to early 1940s

editBarnsdall formally donated Hollyhock House to the government of Los Angeles on December 22, 1926, along with some of the surrounding land, which became Barnsdall Art Park.[101][103][104] As part of the agreement, the California Art Club leased the main house for 15 years.[104][105] The Los Angeles City Council accepted the deed to the house in January 1927.[106] The club kept the main house largely intact, except for two guest bedrooms, which were merged into a single gallery.[62][107] The California Art Club moved into Hollyhock House on August 31, 1927, with a reception attended by 1,000 people;[108] it began inviting regular visitors two weeks later.[109] The main house was used for exhibitions, performances, meetings, receptions, and luncheons,[110] and its central courtyard also hosted performances.[107] Also in August 1927, Barnsdall donated Residence A to the city,[77] and that structure reopened as a recreation building the next February.[111][112] Barnsdall attempted to donate Residence B as well, but the city government would not accept the gift,[113] so she moved there and asked Schindler to remodel it in 1928.[114] She tried to lease one guest house to a Dalcroze eurhythmics dance group,[115][b] and she tried to convert Residence B into a dance club for the elderly[116] and a women's club.[113][117]

Flood lights were installed outside the main house in 1930.[118] Barnsdall threatened to take back ownership of Hollyhock House the next year, amid a dispute over additional land for Barnsdall Park.[119] The California Art Club also wanted to expand its space by roofing over the central courtyard, though Lloyd Wright instead suggested extending the galleries on the house's south wing. Ultimately, the club elected not to expand the house, citing the short duration of its lease.[114] Barnsdall sued the California Art Club in 1938, claiming that the club had failed to maintain Hollyhock House and build an access path from New Hampshire Avenue, thereby violating the terms of its lease.[120] By the next year, the lawsuit was on hold, and Barnsdall tried to sell the land surrounding the house.[121] Around the same time, the floor of the pergola was replaced.[62] A judge ruled in 1941 that Barnsdall could take back ownership of Residence B, while the city of Los Angeles could keep the remainder of the Olive Hill estate, including Hollyhock House.[62] The city's land and Barnsdall's property were separated by the park's internal driveway.[122] Barnsdall retained Residence B until her death in 1946, when she bequeathed that residence to Betty.[123]

The California Art Club vacated Hollyhock House in 1942,[124] at which point the house was in an advanced state of disrepair.[113][114] The park's head gardener claimed that there were severe termite infestations.[125] and two of the art-glass windows were removed for safekeeping until 1984.[126] The main house was unoccupied until 1946,[125][127] when Dorothy Clune Murray signed a 10-year lease and agreed to restore it.[113][128] At the time, the house was about to be demolished.[129][130] The foundation had to spend at least $25,000 on renovations within a year, and artists had to be allowed to meet at Hollyhock House free of charge.[127] Lloyd was hired as the architect for the project,[65][131] which was the house's first major restoration.[113] Lloyd's modifications included the addition of a galley kitchen,[131][132] which replaced the original kitchen.[133] These renovations were finished in 1948[113][128] at a total cost of about $200,000.[129] Hollyhock House was dedicated on November 4, 1948, in honor of James William Clune Jr. a soldier who had been killed in World War II.[134] The United Service Organizations subsequently used Hollyhock House as a clubhouse.[132]

1950s to early 1970s

editIn the early 1950s, the elder Wright was hired to design an art pavilion next to the original house,[128][135] which, at the time, was the only art gallery he had designed.[136] The pavilion measured 230 by 21 feet (70.1 by 6.4 m) across and cost $70,000;[128] it opened in June 1954[137] with an exhibition dedicated to Wright's work.[138][139] Residence B was demolished the same year.[113][128][140][c] During the 1950s, the city created a master plan for Barnsdall Art Park, which would have included an art gallery next to the house.[138][141] Wright was hired as a consultant for this master plan,[142] which was not carried out.[128][138] The Los Angeles city government took over the house in 1956,[143][138] though a news article from 1961 still listed the Olive Hill Foundation as a tenant.[144] By the early 1960s, Hollyhock House hosted events such as meetings, art shows,[145] civic events,[143] concerts,[146][147] and daily tours.[148] Residence A became the Barnsdall Arts and Crafts Center.[149] The city government considered relocating its Municipal Arts Department from City Hall to Hollyhock House in the early 1960s.[150] The Municipal Arts Department took over the main residence, while the Recreation and Parks Department operated Residence A.[151]

In 1964, a second master plan for Barnsdall Park was published;[152][153] as part of this master plan, Hollyhock House's temporary art gallery was to be demolished.[152] Municipal Arts Department director Kenneth Ross led efforts to renovate the house,[154] and the city's Bureau of Public Buildings recommended in 1967 that Hollyhock House be renovated.[145] The next year, the City Council approved $100,000 for Hollyhock House's restoration.[155][156] Marvin S. Levin was hired to oversee the restoration, with Lloyd Wright as consulting architect.[155] The damaged woodwork was replaced,[141] and architectural details were restored.[155] Residence A was renovated as well;[157] the art center there had closed after the completion of the Junior Art Center in 1967.[143] The house's art gallery was demolished in 1969[158] and replaced with the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in 1971.[138][159]

A Los Angeles Times writer said in 1973 that the "snail's-pace renovation" was still not complete.[160] In 1974, Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley requested that the City Council provided $500.000 from the City Council to complete Hollyhock House's renovation,[130][161] which was subsequently approved.[162][163] Workers repaired the foundation, upgraded mechanical systems, reproduced the original furnishings and woodwork, and repainted the house.[164] Eric Lloyd Wright, Frank's grandson, later recalled that the renovation had come amid increasing public interest in his grandfather's work.[165] Hollyhock House temporarily reopened in July 1974, hosting a fundraiser for Los Angeles councilman Arthur K. Snyder.[166] A citizen sued, claiming that the fundraiser violated both the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and a state law prohibiting unauthorized political activity in public buildings,[167] and Snyder later agreed to pay $250 to settle the suit.[168] There were also disputes over how the house should be used.[169]

Historic house museum

edit1970s to 1990s

editThe house reopened to the public on October 16, 1975,[170] and was originally used for municipal government events.[163][171] A volunteer group, Las Angelitas del Pueblo, gave guided tours of the house on Thursdays.[164][172] When Hollyhock House's renovation was completed in 1976, it became a historic house museum.[158][170] Some events could not be hosted in the building; for example, the City Council banned councilmember David S. Cunningham Jr. from hosting his wedding there.[173] By the late 1970s, the house hosted tours three days a week,[171] and it had 8,000 annual visitors.[174] Lloyd Wright said the house attracted groups from Japan who were interested in his father's architecture.[175] The cultural heritage division of the Municipal Art Department took over the house's management in 1978. At that point, there were plans to create the Friends of Hollyhock House (FOHH), a group for the house's docents.[176]

By 1981, the house was open four days a week on alternating weeks,[177] but there were not enough docents to lead the tours.[178] After multilingual tour guides were hired two years later, Hollyhock House began offering tours in six languages.[179] By 1985, the house had about 75 docents, who worked at least four hours per month.[180] Due to increased tourism, the house was open five days a week during some weeks.[180][181] The Los Angeles city government also began allowing researchers to access the house's private research library.[182] In addition, FOHH began raising money for replicas of the original furniture.[161][183]

The city government considered renovating the house again during the late 1980s as part of a larger restoration of Barnsdall Park.[169] By then, the house needed to be repainted and re-caulked, and the roof needed to be patched; the house's curator, Virginia Kazor, compared its maintenance requirements to those of the Golden Gate Bridge.[184] Archiplan and Martin Eli Weil were hired to design the renovation.[169] Workers were repainting the house and replacing the roof and carpets by 1989.[185] Weil had trouble determining the original paint colors until he looked at paint flakes that had fallen into the living room's light bulbs.[65] The living room was renovated and re-furnished in 1990,[186][187] and two of the facade decorations were stolen the same year.[188] The house would have received an additional $2.78 million for restoration as part of California Proposition 1,[189] a $298.8 million bond issue that voters rejected in June 1991.[190] After the furniture was restored, Kazor planned to replace the carpeting.[161]

The structure's finials, living room fireplace, foundation walls, and garden walls were damaged in the 1994 Northridge earthquake.[191][192] Despite up to $750,000 in damage, much of the house remained intact.[191] The Federal Emergency Management Agency and the city government provided funds for the building's restoration.[193][194] The city government hired the landscape architect Peter Walker[194][195] and local preservationist Brenda Levin to design a master plan for the park and house.[194][196] The plans included adding a cafe next to the motor court.[195] Plans for seismic upgrades at Hollyhock House were submitted to the City Council in 1998, at which point the upgrades were to cost $6 million.[197] Although the house was still open to visitors, it continued to decay.[80][198] Scaffolding had to be installed near the entrance, and there were water damage and cracked walls.[198] Delays in constructing Los Angeles Metro's Line B had also forced the postponement of $1.4 million in repairs to the house.[196]

2000s and early 2010s renovations

editOn April 10, 2000, the building was again closed to the public for a renovation and seismic retrofit.[193][199] The project was originally planned to take three years and cost $10 million; it was part of a larger restoration of Barnsdall Park.[193] At the time, the building had water damage on its floors, peeling plaster on its ceilings, and cracks on its walls.[199] In addition, the second floor was severely damaged.[193] The Recreation and Parks Commission awarded a $9.9 million contract for the building's restoration in 2001.[200] Melvyn Green was hired as the house's structural engineer.[132] The first phase of the renovation involved seismic upgrades,[200][201] as well as stabilizing the land under the house.[194][202] Workers installed I-beams to reinforce the upper sections of the house.[203] Workers also rebuilt part of the frieze and added a waterproof membrane to the roof.[201] Although the roof repairs had been finished by February 2003, city officials had not deemed the building safe for occupancy.[204] The estimated cost had increased to $17.1 million, and no funding had been allocated to architectural restoration. The high costs were in part because the city government had wanted detailed plans for the restoration.[11]

Water damage persisted in spite of the roof repairs,[202] largely due to clogged drains.[205] A second phase of renovations began in December 2003.[206] The project included renovating the interior, removing mold and termite-infested wood, replacing corroded pipes and rotting woodwork, and fixing leaks.[201][206] In addition, a replica of the house's original carpet and one of the original reading tables was acquired.[132][202] The house was made partially wheelchair-accessible, but full wheelchair access was deemed infeasible for historical-preservation reasons.[202][207] Following delays, Hollyhock House reopened in June 2005,[206][208] hosting tours four times a day.[209] City officials planned to spend another $2.5 million each on seismic upgrades to Hollyhock House and Residence A.[202] Later the same year, the California Art Club returned to the house for the first time in more than six decades, repainting the building.[210]

The California Cultural and Historical Endowment gave $1.935 million to the nonprofit Project Restore in 2008, which would fund a third phase of Hollyhock House's restoration.[211][212] The city government provided a matching grant of $1.935 million,[54][212] and the National Park Service gave another $489,000 through the Save America's Treasures program.[54][213] In 2011, the city government announced a further $4.3 million renovation.[213][214] Jeffrey Herr, the house's curator, planned to restore the windows, porch floor, and fountains; strengthen the living room fireplace; and renovate a chauffeur's house and garage on the site.[213] The house closed again when the restoration began in 2013.[215] The project included repairs to the roof, the restoration of original architectural details, and the construction of a visitor center in the garage.[215][216] Workers also restored the original windows and repainted the building.[205][54] Historically inaccurate design features, such as glass doors, were removed.[205]

Mid-2010s to present

editThe main house reopened on February 13, 2015, with a 24-hour-long open house,[217] which attracted thousands of people.[218] The second story was closed off because it was not wheelchair-accessible.[207] As such, in 2017, the Los Angeles City Council provided funding for the creation of a virtual reality tour program,[70][219] which was completed the next year.[220] The same year, thecity government began renovating Residence A for $5 million.[221] The work was overseen by Project Restore[222] and involved exterior restoration, seismic retrofits, and mechanical upgrades.[221][222] The same year, the NPS gave the Los Angeles government a $500,000 Save America's Treasures grant for Residence A's restoration.[223][224] At the time, Residence A had several structural defects, including crumbling masonry and incorrectly-installed structural beams.[223]

The main house had about 30,000 annual visitors by the late 2010s,[225] and visitors were allowed back into the living, dining, and conservatory rooms in 2019.[226] The next year, the house was forced to close due to the COVID-19 pandemic in California.[222] The balcony doors, the fireplace, and two sofas in the main house's living room were restored during the closure,[227][228] as were the art glass, cast stone, and woodwork.[229] After Phase 1 of Residence A's renovation was completed in December 2021,[230][221] workers began refurbishing its interior and landscape.[221][222] The main house reopened in August 2022.[228][231]

Architecture

editHollyhock House was the first house in Los Angeles[10][232][132] and in Southern California designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.[233] It is also one of seven houses that Wright designed in Greater Los Angeles[234][235] and the only one that is regularly open to the public.[236] Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra were also involved in the house's design.[232][237] The house is named after Aline Barnsdall's favorite flower, the hollyhock,[124][238] which Wright also liked.[81] Hollyhock motifs are used not only throughout the house's interior and exterior, but also on external features such as lampposts.[130]

The house was designed in a style that Wright characterized as "California Romanza",[141][194] borrowing from a musical term translating to "freedom to make one's own form."[239] The style has also been described as having Asian, Aztec, Egyptian, and Maya architectural influences.[240][241] Dezeen cites the building as one of the first Mayan Revival structures,[233] while the Los Angeles Times describes the building as having had Inca, Native American, and Spanish Colonial architectural features.[241] A New York Times writer likened the building to an adobe building from the American Southwest.[242] Hollyhock House's curator Jeffrey Herr described it as Wright's first post–Prairie style design.[243]

The house is arranged around a central courtyard and a complex system of split levels, steps, and roof terraces.[244][245] Excluding the external terraces at ground level, Hollyhock House measures approximately 121 by 99 square feet (11.2 by 9.2 m2) across.[238] Barnsdall also wanted a house that was "as much outside as inside".[246] As such, the house's interior spaces had design elements typically reserved for exteriors, such as porches, pergolas, and outdoor sleeping spaces,[228] and the windows originally lacked draperies.[247] Although the house overlooks the Pacific Ocean to the west, the design largely faces inward, rather than taking advantage of the topography.[248][249] In keeping with Wright's tendency toward organic architecture, the house is low to the ground.[247][250] In addition, the house was originally not readily visible from the street because of the plantings around it.[18]

Exterior

editThe walls are made of hollow clay tiles and wood frames covered with stucco.[161][251][252] At the bottom of the facade is a water table of cast concrete.[238][d] Concrete belt courses, as well as concrete friezes with hollyhock patterns, cross the facade horizontally about 6.5 to 8.0 feet (2.0 to 2.4 m) above the water table.[238] The hollyhock motifs of the friezes protrude slightly above the top of the facade.[253] Above the friezes, the walls slope inward at a 10-degree angle, similarly to the design of Pre-Columbian temples.[238] The sloping upper walls were similar to the design of Maya temples.[254][255] The exterior also has "dancing triangles", which may have been inspired by crystallographic patterns.[256]

The house's windows and doors are placed within concrete-framed openings. In general, the windows are casement windows with oak frames, and there are French doors extending to the height of the concrete frieze.[257] There are also leaded-glass windows throughout the house,[132] in addition to planters close to the ground.[202][238] Atop the facade are small clerestory windows, which were intended to reduce glare from sunlight.[186] Wright designed art glass windows for the house,[258] which have green and violet art-glass panes, interspersed with white and clear panes.[75][259]

Terraces and courtyards

editOn the northern side of the house is a loggia raised five steps above ground and measuring 68 feet (21 m) long.[238] The loggia is asymmetrical, being located near the northwestern corner of the house, on the west side of the house's motor court.[260][252] At the end of the loggia is an entrance vestibule measuring 3 by 8 feet (0.91 by 2.44 m) across, with cast-concrete floors, walls, ceilings, and a glass-and-wood chandelier.[238] The main entrance has a concrete door weighing 250 pounds (110 kg)[186][247][261] or 300 pounds (140 kg).[252] A pergola on the east side of the motor court led down to the garage building.[245]

Multiple terraces extend from the house, functioning as extensions of the interior rooms.[18][80][250] They are surrounded by stucco-clad parapets measuring 2.5 to 10.0 feet (0.76 to 3.05 m) high.[238] The eastern terrace is three steps above ground and consists of a circular pool,[257][248] which is designed like an amphitheater.[249] The center of the pool has a replica of an ancient Roman bronze sculpture.[255] Next to the pool is a protruding bay with leaded glass windows.[257] Along the house's southern elevation are three raised terraces, in addition to a large balcony just outside the master bedroom on the second story.[238] The south terraces have an upper wall for privacy and a lower wall for sightseeing.[262] West of the house is a 4-by-12-foot (1.2 by 3.7 m) living-room balcony, with slightly raised terraces on either side.[238] There is also a square reflecting pool to the west, complementing the circular pool on the east.[238][248]

The central courtyard is also known as the patio.[263] It is surrounded by glazed doors and windows,[257][264] which were intended to draw attention to the courtyard from inside the house.[264] The southern wall of the courtyard has a wooden pergola with glass windows, while the northern wall has a colonnade with hollyhock motifs. On the western end of the courtyard, sliding glass-and-wood doors lead to the living spaces, and a concrete staircase ascends to the roof.[257] The staircase is flanked by finials.[265] At the eastern end, the second story crosses over the courtyard,[248][257] creating a square archway.[186] Under the arch is a 16-by-26-foot (4.9 by 7.9 m) area connecting the courtyard with the circular pool to the east.[257] The courtyard and the circular pool are separated by a flagstone walkway.[249]

Roofs

editThe house has flat roofs,[202][250] which are placed at different levels, creating the impression of terraces.[244][245] A contemporary source from the house's construction described the roofs as a "mezzanine roof-garden".[245] As built, the roofs had protective wool membranes covered with tar and canvas, and they were supported by wooden studs at 16-foot (4.9 m) intervals. The outer perimeter of the roof has a parapet measuring 18 to 22 inches (460 to 560 mm) tall.[257] Water on the roof was drained by pipes inside the house;[257] the designs of the roofs, planters, and openings made the building vulnerable to flooding during heavy storms.[202] Before deciding on a flat roof, Wright had considered a hip roof and a tepee–shaped roof.[253]

Staircases connect the different roof levels.[257][253] The design of the roofs led one newspaper to characterize the building as having a "roof observatory", from which visitors could see the ocean and the nearby mountains.[253] Had the house been used for performances as intended, the roofs could have accommodated crowds who were viewing performances at the eastern pool.[248][249]

Interior

editBarnsdall envisioned the house not only as a family home, but also as a symbol of her status as the head of a theatrical company.[266] Hollyhock House is cited as spanning 6,000 square feet (560 m2),[132][186][238] with five bedrooms.[18][132] Sources disagree on whether the house has six[132] or seven bathrooms.[267] In addition, the building is cited as having either 15,[174] 17,[267] or 18 rooms.[74]

The house has a U-shaped floor plan,[257][266] a layout inspired by the designs of several of Wright's houses.[268] The rooms are arranged around a north–south axis, aligned with the entrance loggia, and a west–east axis, aligned with the house's pools.[257][260] The rooms are arranged into three groups: the living and music room wing to the west, the dining and kitchen wing to the north, and the bedroom wing to the south.[264][269] The second floor of the bedroom wing crosses over the eastern side of the courtyard.[245][269] Each group of rooms is separated from the others by hallways and loggias,[264][269] and differing ceiling heights delineate the boundaries between some rooms.[250] According to Jeffrey Herr, the house's layout did not give visitors cues as to where they should go, unlike in typical houses where rooms led into one another.[243]

In general, non–load-bearing interior walls are made of wood studs coated in plaster, while the wooden floor planks are fitted together in a tongue-and-groove pattern.[259] A lavender, beige, and mauve palette was used throughout the house.[174] Barnsdall allowed Wright to furnish the house with Japanese-inspired decorations, such as Japanese screens and a Buddhist sculpture.[228] There is built-in furniture throughout the house, including shelves and drawers, as well as toilets that are hung from the wall.[247] Fireplaces and heaters were embedded into the walls.[186] Wright designed furniture for the house, most of which has been removed over the years.[186][250] Sources disagree on whether he designed furniture for the whole house,[161] or only for the dining and living rooms.[270][271]

Living and music room wing

editThe entrance hall from the north leads to an interior loggia that connects with various rooms.[272][257] The interior loggia, also known as the porch, runs along the western side of the central courtyard.[273][274] As built, there were glazed panels leading to the courtyard and double doors to the living room.[274] The loggia has a pair of planters,[273] and it displays a replica of an ancient Roman relief, Three Dancing Nymphs, which Barnsdall acquired in 1921.[271][275] The living room and music room are to the west of the interior loggia, on the right side of the entrance hall.[257]

The music room is separated from the entrance hall via a screen of wooden slats.[272] It had two built-in wooden cabinets on its northern wall and one on its eastern wall, which were removed in the late 1940s;[276] the other original furnishings are poorly documented.[277] The space may have contained a piano or a gramophone. In addition, there are cabinets, which date from Lloyd Wright's 1970s renovation.[276][277] There is a set of French doors on the western wall, which lead to a terrace north of the living room.[276] Originally, the floor of the music room and adjacent living room had a multicolored carpet made by W. & J. Sloane, with a hollyhock–inspired pattern.[278]

The living room is one step down from the adjacent rooms[276] and is shaped as a double-square.[269][279] The walls were originally painted in gold[187] and contain oak wainscoting.[259] On the south wall is a large protruding fireplace with a mantelpiece made of cast stone and surrounded by a moat.[132][193][279] The moat is connected with the house's pools via an underground pipe,[186][272] but the water feature was turned off because it did not work properly.[49] Above the fireplace is a bas-relief sculpture,[49][276] which is made of cast concrete.[49][272] There is a skylight on the ceiling above the living room's fireplace.[132][272][279] The room has oak furniture as well;[280] the backs of the armchairs are sloped at the same angle as the walls, and the tables have torcheres that illuminate the ceiling.[75] The walls are decorated with two Japanese screens.[193][280] A French door leads west to the living-room balcony, and another door on the south wall leads to a terrace.[276] The ceiling of the living room, measuring 12 feet (3.7 m) high,[247] slopes upward and has oak moldings,[276][272] along with bronze and light green bands.[245][187] Light bulbs are recessed into the ceiling.[259] The living room also includes three side chairs, an upholstered chair, and a table designed by Wright.[259]

There is an alcove to the south of the living room, which has French doors facing west toward another terrace south of the living room.[276] South of the alcove is a private study, which is not connected to the living room and can be accessed only through a short corridor leading off the home's hallway.[276][281] The study has three tables dating from 1946, as well as a replica collection of books and artwork.[281] The short corridor also leads to a conservatory with a south-facing terrace.[276][282] The conservatory, also known as the breakfast room, originally had cabinets and a table; it was intended as a tearoom for Barnsdall, her daughter, and their guests.[282] Both the study and the conservatory also connect with a terrace to the west.[276]

Dining and kitchen wing

editTo the left (east) of the entrance hall is the dining/kitchen wing.[257][271] This wing is four steps above the entrance hall[252][257] and runs along the north side of the central courtyard.[245][283] The dining room sat six people,[75][259] as Wright believed that this was the optimal size of a dinner gathering.[18][46] The furniture has hollyhock motifs that are arranged in a pattern resembling vertebrae.[270][271] The chairs were made by Barker Bros.[270] and are similar to those in Wright's Prairie style homes, with flat backs and low seats.[228] The walls are wainscoted in hardwood planks.[259] On the eastern end of the dining room, a set of built-in sliding drawers flanks the doorway to the kitchen.[257] French doors lead south into the courtyard, while smaller leaded-glass windows illuminate the north wall.[257][262] The low ceiling slopes up toward the south wall.[257] There is a light fixture at the center of the ceiling.[257][284]

The original kitchen's design has not been fully documented, but there is evidence that the original kitchen had a pantry and was decorated with pine and maple wood.[285] The design of the modern kitchen dates to a 1946 renovation by Lloyd Wright.[133][285] The current kitchen has a stove and mahogany counters, in addition to angular and horizontal motifs.[285] To the east of the kitchen are the servants' quarters—with a living room, a bathroom, and two bedrooms—as well as a stair to the basement.[276][286] The servants' quarters, later converted into staff offices, were furnished with pine and had painted walls. The basement had storage rooms and laundry rooms.[286]

Gallery and bedroom wing

editThe bedroom wing is on the south side of the central courtyard[276][283] and is the only part of the house that is more than one story high.[264] A pergola with glass windows runs next to the courtyard, separating the court to the north and the gallery to the south.[276][287] The doorway leading south to the gallery was added in 1946,[287] and a wire glass roof and plastic ceiling were added in 1974.[276] A sculpture of the Buddhist goddess Guanyin is also placed in the pergola.[288] The gallery to the south was created in 1927 when the California Art Club merged two adjacent guest bedrooms.[276][289] This gallery has hardwood flooring, Plexiglas panels, and fluorescent ceiling lamps.[276] The original bedrooms were separated by a short hallway that connected with a terrace to the south.[289]

On the first floor was a set of rooms for Barnsdall's daughter Betty, which included a bedroom, bathroom, playroom, and caregiver's room.[276][290] The bedroom had a separate dressing area, which had vertically oriented art-glass windows.[290] The bedroom also had a fireplace with cast concrete decorations;[276] Wright had proposed adding a decorative panel above the fireplace, with motifs of the moon and balloons, the panel was never completed.[290] The playroom had art-glass casement windows,[276] and there was a portrait of Aline.[65] Betty's caregiver had a separate bedroom that was connected to the main hallway and to a bathroom;[290] this bedroom had a Murphy bed designed by Wright.[262] In addition, there was an enclosed sun porch with art-glass windows.[291] Betty's bedroom was also used as a women's lounge after the Olive Hill Foundation took over in 1946.[292]

Barnsdall's master bedroom was on the second floor, above her daughter's bedroom.[264] Within the eastern part of the master bedroom, two steps descend to a sleeping porch.[293][294] Originally, this bedroom had a futon that could be pulled out of the closet, which Barnsdall disliked.[80][261] On the southern wall are art-glass French doors, which connect to a balcony above Betty's playroom, while on the west wall are a fireplace and a stair to the second-story roof.[293] Schindler redesigned the bedroom several years after Barnsdall moved in.[276][292] A wooden screen separated the sleeping porch from the remainder of the room, although Lloyd Wright removed these decorations in 1947.[262][276] When the Olive Hill Foundation occupied the house, the master bedroom became a men's lounge.[292]

Also on the second story is a passageway,[255][259] which is illuminated by three clerestory windows and has a door to the roof terraces.[259] The passageway crosses over the eastern end of the central courtyard, connecting the master bedroom to the south with a guest bedroom to the north.[245][276] A stairway leads from the guest bedrooms to the roof terraces.[245]

Associated structures

editBarnsdall had proposed developing multiple structures around Hollyhock House,[13] including an actors' dormitory, a director's house, workshops, art studios, and two theaters.[161][82] Ultimately only two guest houses (Residences A and B) were built, of which only the former still exists.[13][235][161] Residence A is located northeast of the main house, while the garage building is located north of the main house. To the southeast is Schindler Terrace and the Spring House.[295] Barnsdall also commissioned a private kindergarten, which was never built.[69][78][296]

Residence A

editResidence A, designed by Rudolph Schindler, is similar in design to Wright's earlier Prairie-style houses.[297] It is slightly south of the intersection of New Hampshire Street and Hollywood Boulevard.[63] Residence A measures 67 by 45 feet (20 by 14 m) across and is arranged in a T shape, with the top of the T facing northward.[298] The building is two stories tall, except on its north side, which has a third-story penthouse.[299] The northern facade has a rectangular massing, like Wright's Unity Temple and Bogk House, while the southern and eastern facades have low roofs at different levels, akin to his Frank Thomas House and Robie House. The thick-looking concrete walls resemble those in Maya temples.[297] Similarly to the main house, Residence A has wood-frame, clay-tile, and stucco walls with concrete decorations.[299] The roof has cantilevered eaves, and the house's eastern, northern, and western elevations have parapets above their roofs.[298]

The northern elevation of Residence A's facade has five cast-concrete window openings and a wooden balcony. The western elevation has wood-framed windows and a set of double doors leading from a concrete courtyard. There is also a wood staircase, in addition to several casement windows and clerestory windows on the western elevation's second story.[299] Two wood-frame annexes abut the western elevation. The southern elevation has a cast-concrete band.[298]

Within the building, the northern end of the T-shaped floor plan is a double-height space. Residence A's main entrance leads to a foyer with a concrete floor and a 7-foot-high (2.1 m) ceiling. To the east of the entry hall, two steps descend to an office. There is also a service room and a workroom (originally bedroom) to the south or right, as well as a living room with a double-height ceiling to the north or left. A staircase ascends to the second floor, where there is a dining room, kitchen, storage room, and another room (originally two bedrooms).[300] In general, Residence A has wood-plank floors, except the basement, which has plain concrete slabs. The non–load-bearing walls are made of wood studs and coated in plaster, while the load-bearing walls are made of masonry and coated with plaster. The ceilings are also made of plaster, although there are ornamental cornices in the living room and entrance foyer.[300]

Garage building

editNorth of the main house is the garage building, which also contains the chauffeur's residence;[213][301] it measures about 23 by 74 feet (7.0 by 22.6 m) across.[302] It has very few windows. The building is located on a slope, so the northern end is two stories below the southern end. The automobile court is at the southern elevation of the house, where there is parking space for three vehicles. There is also a porch measuring 17 by 20 feet (5.2 by 6.1 m) and raised two steps above the ground. The entrance to the chauffeur's residence is on the northern elevation, accessed by a stoop with four steps. Similarly to the main house, the facade has stucco cladding above a cast-concrete water table, although it differs from the main house in that there are few windows. The top of the facade doubles as a parapet for the flat roof, sloping inward above a concrete belt course and frieze.[302]

The building's interior has been drastically modified over the years.[302] After the city of Los Angeles took over the building, the garage served as a restroom for park visitors.[251][302] The restrooms were in operation from c. 1962–1963 to 1990 and occupy the garage's easternmost parking space and the chauffeur's quarters. The westernmost parking space has a half-bathroom, while the remainder of the garage has a kitchen, office, storeroom, and mechanical room.[302] There are 15 animal cages connecting the garage with the main house, although it is unknown which animals were kept there.[295][301] The cages are arranged in a straight line and have concrete water tables, concrete-slab floors, stucco walls, and flat roofs.[301] By the 2010s, the garage building was used as a visitor center.[295][303]

Other structures

editThe Spring House, on Olive Hill's southeastern slope next to the Junior Art Center,[295][300] is the former refrigeration facility.[295] It measures 10 by 18 feet (3.0 by 5.5 m) across with a concrete water table, brick exterior walls, stucco cladding, and a belt course and frieze made of cast concrete. Similarly to the main house, the Spring House's walls slope inward above the frieze. In addition, there is a stair to the west and a doorway to the south.[300] A trough extends east from the house, connecting with a concrete pool and a dry streambed; this was part of a watercourse that Wright had designed for the property. Inside the Spring House is one room with a rectangular pool, benches, and a sloped ceiling.[304] Next to the Spring House is Schindler Terrace, the site of an unbuilt community theater.[295][71] Schindler Terrace includes a lawn in the center, a paved area at its south end, and a small pool and pergola at its north end.[71]

Residence B was located at 1610 North Edgemont Street,[305] on the western slope of Olive Hill, and had 12 rooms.[117] The western elevation was four stories high, while the eastern elevation was one story.[117] The house was divided into three sections: living spaces, service rooms, and bedrooms. The living room had a balcony overlooking the Pacific Ocean to the west. The bedroom section had three bedrooms, a balcony for sleeping, two-and-a-half bathrooms, and two servants' rooms.[306] These rooms surrounded a large brick fireplace at the center.[307] The facade was sparsely decorated and was decorated with horizontal lines.[306]

Management

editTwo groups help maintain Hollyhock House.[202] The Barnsdall Art Park Foundation, a nonprofit organization, helps manage Barnsdall Art Park and the activities there,[308] including the house.[64] The Friends of Hollyhock House (FOHH) is a private group that helps raise money for the house itself.[213] After Hollyhock House reopened in 2015, it has also hosted art installations. For example, artwork was projection-mapped onto the house for the first time in 2016,[309] and the building hosted its first contemporary art show in 2023.[310] In addition, a digital archive of documents relating to Hollyhock House was established in 2020.[311]

Tours are given by a group of volunteer docents.[312] On February 13, 2015, self-guided "Walk Wright In" tours commenced,[216][313] running Thursdays through Sundays.[314] In addition to the self-guided tours, there are docent-led tours three times a day on Thursdays through Sundays, as well as extended docent-led tours twice a day on Tuesdays and Wednesdays.[314] Tours were paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic but resumed on August 18, 2022.[231] There is also a website with virtual tours of the house's interior.[220][226] Throughout Barnsdall Park are QR codes, which in turn link to videos and virtual tours of the house.[222][315] Because the house has no air-conditioning, it closes when the rooms' temperatures exceed 90 °F (32 °C).[303]

Impact

editCritical reception

editWhen the house was under construction, the Evening Citizen News wrote that the building was "a home, not just a house" and that the hollyhock motif was pleasing and ubiquitous.[245] A writer for the Conde Nast Traveler wrote that "modernism actually arrived" in Los Angeles when Hollyhock House was finished.[64] The Evening Post-Record, in 1923, likened Hollyhock House and surrounding buildings to a Tuscan villa.[90] The same year, the Evening Express described the site as being unsurpassed in beauty,[91] and the Los Angeles Times characterized the house as one of Los Angeles's finest residences and that East Hollywood "can consider itself unusually fortunate".[316] A writer for the Times compared it to a villa in Venice, Italy.[317] A newspaper from the 1950s called Hollyhock House "one of the most important architectural contributions to the community".[318] The Los Angeles Mirror wrote in 1961 that the house's materials, Mayan decorations, and varying levels contributed to its character.[319]

After the house was renovated in 1975, the Press-Telegram wrote that the house was "considered an outstanding example of [Wright's] genius in fitting a building to a site".[164] The Topanga Messenger said the house "was built as a showpiece, yet maintains an intimacy throughout",[320] while another local newspaper called it "large, heavy, boxlike".[46] A Los Angeles Times writer said in 1990 that the house still had a "magical" quality, despite years of municipal ownership and decay,[321] and a writer for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette described the house as "a rare pleasure".[186] A critic for The Baltimore Sun praised the architecture, interior layout, and spatial elements,[322] and a New York Times reporter similarly praised the clerestory windows and high ceilings as encouraging circulation.[242] When the house reopened in 2005, the Daily Breeze of Hermosa Beach, California, wrote that the building was "rich, complex, intriguing and at times even awe-inspiring."[132] The Architectural Record wrote that Hollyhock House "stands in an arena of its own",[240] and Christopher Hawthorne of the Los Angeles Times regarded it as "underappreciated and largely misunderstood".[323]

Conversely, the structure was not highly regarded among fans of Wright's work. James Steele, an architecture professor at the University of Southern California, said the building was often viewed as "a folly that was totally out of character and context of his work".[324] A reporter for the Los Angeles Times wrote that the house had "one of Wright's least appealing domestic interiors" and that the surrounding grounds were as "depressing" as a convenience-store parking lot.[51]

In 1959, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) deemed Hollyhock House as one of several buildings designed by Wright that merited the highest levels of architectural preservation.[128][325] A panel of prominent Angelenos listed Hollyhock House among Los Angeles's 12 top landmarks in 1967,[145][326] and the house was included in a list of all time "top ten" Los Angeles houses in a Los Angeles Times survey of experts in December 2008.[327] In addition, Paul Goldberger of The New York Times said in 1980 that Hollyhock House was one of several early modern–styled houses in Greater Los Angeles that were well-known.[328]

Landmark designations

editHollyhock House is a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument,[222] having been listed as such in January 1963.[26][329] It was one of Los Angeles's first municipal landmark designations.[330] Residence A and the rest of Barnsdall Park were also designated as a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 1965.[331][332] The entire estate was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971,[26] and the U.S. Department of the Interior designated Hollyhock House and Residence A as part of a National Historic Landmark called Aline Barnsdall Complex on April 4, 2007.[333] It was one of three Wright buildings designated as National Historic Landmarks on the same date,[334][333] as well as the seventh site in the city of Los Angeles to receive that designation.[335]

The United States Department of the Interior nominated Hollyhock House to the World Heritage List in 2015, alongside nine other buildings.[336][337] UNESCO added eight properties, including Hollyhock House, to the World Heritage List in July 2019 under the title "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright";[296][338] this made Hollyhock House the first World Heritage Site in Los Angeles.[323] A plaque memorializing the World Heritage designation was installed in February 2020.[124][339]

Architectural influence and media

editThe New York Times wrote in 2005 that the Hollyhock House "represented a turning point in Southern California architecture", since it had helped start the careers of Rudolph Schindler, Richard Neutra, and Frank's son Lloyd.[194] Following Hollyhock House's construction, Schindler decided to stay in California, eventually opening an architectural firm of his own.[340] The design of Wright's West Hartford Theatre near Hartford, Connecticut, was partly inspired by that of the Barnsdall estate's unbuilt theater.[341] Hollyhock House's design may have inspired that of early ranch-style houses.[243][342] The architect Harwell Hamilton Harris reportedly decided upon his career after seeing Hollyhock House,[343] and other architects such as John Lautner and Gregory Ain have cited Hollyhock House as an inspiration.[315]

In spite of Wright's fame, the first books specifically dedicated to Hollyhock House were not published until 1992.[324] The house was also used as a filming location for the 1988 movie Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death,[205][344] as well as for True Detective season 2.[344] By the 2010s, the city no longer allowed film shoots at the house.[205] Several museum exhibits have featured design elements from the house. For example, the dining suite was the focus of a 1976 exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art,[345] and a chair from the house was exhibited around the U.S. in 1979.[346]

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ Among other things, the city would have been required to spend $10,000 annually on upkeep and keep a fire burning continuously for six months. It would have also been banned from planting palms or geraniums, building a war memorial, or removing existing flower beds.[97]

- ^ Sources disagree on whether Residence A[89] or Residence B would have hosted the dance classes.[113]

- ^ News articles from March 1954 misattributed Residence B as the Hollyhock House.[140]

- ^ Some sources, such as the architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock, incorrectly cite the entire facade as being made of cast concrete.[252]

Citations

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Aline Barnsdall Complex". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- ^ Department of City Planning. "Designated Historic-Cultural Monuments". City of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ^ "Barnsdall Art Park". The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ Fodor's Los Angeles: with Disneyland & Orange County. Full-color Travel Guide. Fodor's Travel. 2014. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8041-4249-6. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ "Barnsdall Art Park". City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c Smith 1992, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Levine 1997, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e f Sutherland, Henry (March 15, 1970). "Strange Saga of Barnsdall Park". Los Angeles Times. pp. C1, C2, C3. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 16, 2025.

- ^ a b Rivera, Carla (May 30, 2000). "Popular Barnsdall Art Park Prepares to Close for Up to Year for Upgrade". Los Angeles Times. pp. B11, B16. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b Boehm, Mike (June 1, 2003). "Some unfinished business". Los Angeles Times. p. E40. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 421840305. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ Madsen, David (2012). L.A. Adventures: Eclectic Day Trips by Metro Rail Through Los Angeles and Beyond. L.A. Electric Travel Books. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-9850885-3-8. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ a b c Rauzi, Robin (February 24, 2000). "Itinerary: Barnsdall Art Park". Los Angeles Times. p. 131. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c LSA Associates 2009, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 1992, p. 49.

- ^ Smith 1992, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Meares, Hadley (October 24, 2014). "Barnsdall Art Park: Lofty Ambition Amongst the Olive Leaves". PBS SoCal. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Lockwood, Charles (December 2, 1984). "Searching Out Wright's Imprint in Los Angeles". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ Friedman, Alice T. (2006). Women and the Making of the Modern House. Yale University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-300-11789-2.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 15.

- ^ a b Levine 1997, p. 128.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 20.

- ^ Levine 1997, pp. 128–129.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 25.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d LSA Associates 2009, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Smith 1992, p. 39.

- ^ Auer, James (December 29, 2002). "Wright's grand house at risk ; Taliesin: In Spring Green, Wis., a house that stands for the great American architect the way Monticello stands for Thomas Jefferson, says a Harvard professor, is crumbling". The Baltimore Sun. p. 8L. ISSN 1930-8965. ProQuest 406537968.

- ^ Smith 1992, pp. 22, 30.

- ^ Smith 1992, p. 34.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 1992, p. 50.

- ^ a b "Famous 'Olive Hill', 36-Acre Tract, Sold". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. July 4, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c "For Olive Hill". Los Angeles Times. August 3, 1919. p. 6. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ "Los Angeles to Have Little Theatre". The Peninsula Times Tribune. July 19, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved January 11, 2025; "New Owner of Olive Hill Announces Plan for Future". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. July 11, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ a b Lathrop, Monroe (July 5, 1919). "Olive Hill Playhouse Woman's Fine Project". Los Angeles Evening Express. p. 13. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ a b c Levine 1997, p. 131.

- ^ "Large, Large News and Very, Very, Very Good for Community Theatre". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. August 8, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ Smith 1992, pp. 49–50.

- ^ "The Legitimate: Impetus for Little Theater Movement". The Billboard. Vol. 31, no. 34. August 23, 1919. p. 32. ProQuest 1031584236; "Plans Playhouse in Olive Grove". Spokane Chronicle. Associated Press. August 8, 1919. p. 12. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ "Frank Lloyd Wright at Spring Green". Baraboo Weekly News. October 9, 1919. p. 5. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 51.

- ^ Smith 1992, pp. 51, 56.

- ^ Levine 1997, pp. 129, 131.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Fischer, Del (May 31, 1981). "Frank Lloyd Wright gave L.A. Hollyhock House". Thousand Oaks Star. p. 27. Retrieved January 16, 2025.

- ^ Murphy, William S. (November 11, 1982). "Arts, Crafts, Architecture Make Barnsdall a Popular Park". Los Angeles Times. p. 279. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 16, 2025.

- ^ Smith 1992, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d Brach 2022, p. 17.

- ^ Smith 1992, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Hawthorne, Christopher (July 3, 2005). "Hubris on the hill". Los Angeles Times. p. E29. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 422039603. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b Kellogg, Stuart (November 2, 2001). "An Experiment in Living". Desert Dispatch. pp. 10, 11. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c Smith 1992, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e Amelar, Sarah (February 11, 2015). "The Hollyhock House Comes Into Its Own". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (February 26, 2001). "Breezy Modernist Gets His Due; Honor at Last for an Architect Who Made California His Muse". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Smith 1992, p. 84.

- ^ Smith 1992, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e Smith 1992, p. 83.

- ^ Wright, Frank Lloyd (2005) [1943]. An Autobiography. New York: Horizon Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-7649-3243-4.

- ^ a b c d Sorrell 2009, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Smith 1992, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i LSA Associates 2009, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Smith 1992, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d e Wogan, John (November 18, 2014). "The Making of Frank Lloyd Wright's Hollyhock House". Condé Nast Traveler. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Whiteson, Leon (May 2, 1989). "Architecture : Finding the Wright Stuff for a Hollyhock House Remake". Los Angeles Times. pp. V 1, V 3. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 17, 2025.

- ^ Smith 1992, p. 100.

- ^ Hoffmann 2011, p. 34.

- ^ Smith 1992, pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoffmann 2011, p. 99.

- ^ a b Wick, Julia (April 6, 2017). "Frank Lloyd Wright's Iconic Hollyhock House Will Be Getting Its Own Virtual Reality Tour". LAist. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2007, p. 12.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Smith 1992, p. 165.

- ^ a b "Will Spend Million Dollars on Olive Hill Improvement". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. July 8, 1921. p. 7. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Young, Lucie (April 1, 2006). "Hollywood dreaming". The Independent. pp. 36, 37, 38. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b Kaplan, Sam Hall (February 6, 1988). "Wright Stuff-In and Out of the Gallery". Los Angeles Times. p. 4. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 292731441.

- ^ a b Sorrell 2009, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Smith 1992, p. 173.

- ^ Karasick, Norman M.; Karasick, Dorothy Kesler (January 1, 1993). The Oilman's Daughter. Encino, California: Action Amer Productions. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-881643-24-1.

- ^ a b c d Hardy, Terri (June 10, 1996). "2,000 Applaud Top Architect's Work in City". Daily News. p. N.3. ProQuest 281666548.

- ^ a b Yenckel, James T. (February 1, 1987). "Places and Spaces of Frank Lloyd Wright; Other Wright Sites". The Washington Post. p. E01. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 306864489.

- ^ a b Dubin, Zan (January 24, 1988). "Frank Lloyd Wright—Two Exhibitions". Los Angeles Times. pp. 85. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 17, 2025.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 186.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 187.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2007, p. 17.

- ^ "Offers 'Olive Hill' to City". Los Angeles Evening Express. December 6, 1923. p. 1. Retrieved January 13, 2025; "Miss Barnsdall Offers City Her Estate for Park". Daily News. December 7, 1923. p. 8. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b "Offers Home for Library". Los Angeles Times. December 7, 1923. p. 32. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Makes Park Site Gift to City". Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. December 6, 1923. p. 1. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 1992, p. 194.

- ^ a b Butler, Marjorie (December 13, 1923). "Olive Hill Belongs to You Now; Here's Picture of Gift and Giver". Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. p. 12. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b McClintock, Ruth (December 18, 1923). "Olive Hill's Owner Shuns Interviewer". Los Angeles Evening Express. p. 21. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Oil Magnate's Daughter Will Give 'Hollyhocks' Home to Film Folk". The San Francisco Journal and Daily Journal of Commerce. January 21, 1924. p. 1. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Hoffmann 2011, p. 100.

- ^ "Park Site Gift Is Formally Accepted". Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. December 8, 1923. p. 1. Retrieved January 13, 2025; "Barnsdall Estate Gift is Accepted". Los Angeles Times. December 8, 1923. p. 17. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Body to Accept Barnsdall Home Gift Appointed". Los Angeles Times. December 13, 1923. p. 45. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ "Barnsdall Deed Ready for City". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. February 6, 1924. p. 1. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b "Praise Refusal of Park Offer". Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. April 22, 1924. p. 7. Retrieved January 13, 2025; "Restrictions Too Rigorous for City". Redlands Daily Facts. March 27, 1924. p. 9. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, p. 193.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 2011, p. 101.

- ^ a b "Members of Club Vote for Gallery". Los Angeles Times. April 5, 1925. p. 76. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b "Los Angeles Presented Park Worth $1,000,000 by Barnsdall Heiress". Daily News. December 23, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b "$1,000,000 Tract Is Given Los Angeles". The San Bernardino County Sun. Associated Press. December 23, 1926. p. 2. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Million Dollar Gift Delivered". Los Angeles Times. December 23, 1926. pp. 1, 2. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025; "$1,000,000 Gift for City; Olive Hill Is Yule Present". Los Angeles Evening Express. December 22, 1926. p. 21. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b LSA Associates 2009, p. 6; Smith 1992, p. 194.

- ^ "Art Club Gains Long-Desired Home". Los Angeles Times. December 26, 1926. p. 50. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Olive Hill Deed Accepted by Solons". Daily News. January 6, 1927. p. 9. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b Smith 1992, pp. 194–195.

- ^ "Pasadena Artists at Opening of Art Club". The Pasadena Post. September 1, 1927. p. 5. Retrieved January 13, 2025; "Art Club Takes Over New Home". Los Angeles Times. September 1, 1927. p. 1. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Olive Hill Art Salon Now Open". Los Angeles Times. September 12, 1927. p. 24. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Future Bright for Olive Hill". Los Angeles Times. November 7, 1927. p. 19. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Playground Fete to be Given Today". Los Angeles Times. February 17, 1928. p. 29. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 16, 2025.

- ^ Sorrell 2009, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h LSA Associates 2009, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Smith 1992, p. 195.

- ^ "Dalcroze System of Dancing Urged for Playgrounds". The Long Beach Sun. January 2, 1929. p. 4. Retrieved January 13, 2025; "Dancing Classes Planned for Park". Los Angeles Times. December 24, 1928. p. 19. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Old Folks' Dancing Planned for Park". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. May 4, 1928. p. 7. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ a b c "New Clubhouse Luxurious". Los Angeles Times. February 13, 1931. p. 24. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Art Club Lights to Be Dedicated". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. May 10, 1930. p. 5. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Conference May End Barnsdall Park Row". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. June 15, 1931. p. 2. Retrieved January 13, 2025; "Radical Center Plan Revealed". Los Angeles Evening Express. July 23, 1931. p. 2. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "Miss Barnsdall Sues for Land: Seeks Return of Part of Park Property". Los Angeles Times. February 22, 1938. p. A1. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 164841793. Retrieved January 13, 2025; "Barnsdall Suit Offers Puzzle on Park's Fate". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. February 22, 1938. p. 11. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "For Sale Signs Appear at Barnsdall Park". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. April 13, 1939. p. 12. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ "16 dogs guard barricades in feud; city waves legal gains". Daily News. March 7, 1945. p. 27. Retrieved January 14, 2025; "Miss Barnsdall Warns City As Park Road Blocks Moved". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. March 7, 1945. p. 3. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ "Heiress' Will Provides for Her 15 Dogs". Metropolitan Pasadena Star-News. January 3, 1947. p. 2. Retrieved January 14, 2025; "Miss Barnsdall Leaves $5000 for Her 22 Dogs". Los Angeles Times. January 3, 1947. p. 12. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ a b c Castillo, Andrea (February 23, 2020). "Plaque marks Frank Lloyd Wright's Hollyhock House as L.A.'s first UNESCO World Heritage Site". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Roaming Around With Austin Conover". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. June 12, 1946. p. 9. Retrieved January 14, 2025.

- ^ "Frank Lloyd Wright Windows to Return". Los Angeles Times. May 20, 1984. p. 188. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 17, 2025.