Ballard is a neighborhood in northwestern Seattle, Washington, United States. Formerly an independent city, the City of Seattle's official boundaries define it as bounded to the north by Crown Hill (N.W. 85th Street), to the east by Greenwood, Phinney Ridge and Fremont (along 3rd Avenue N.W.), to the south by the Lake Washington Ship Canal, and to the west by Puget Sound's Shilshole Bay.[1] Other neighborhood or district boundaries existed in the past; these are recognized by various Seattle City Departments, commercial or social organizations, and other Federal, State, and local government agencies.[2]

Ballard | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Ballard and Lake Washington Ship Canal from the south | |

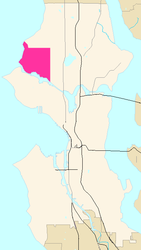

Map of Ballard's location in Seattle | |

| Coordinates: 47°40′37″N 122°23′06″W / 47.677°N 122.385°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| City | Seattle |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (Pacific Daylight Time) |

Landmarks of Ballard include the Ballard Locks, the National Nordic Museum, the Shilshole Bay Marina, and Golden Gardens Park. The neighborhood's main thoroughfares running north–south are Seaview, 32nd, 24th, Leary, 15th, and 8th Avenues N.W. East–west traffic is carried by N.W. Leary Way and N.W. 85th, 80th, 65th, and Market Streets. The Ballard Bridge carries 15th Avenue over Salmon Bay to the Interbay neighborhood, and the Salmon Bay Bridge carries the BNSF Railway tracks across the bay, west of the Ballard Locks.[1]

Ballard is located entirely within Seattle City Council District 6, which also includes the neighborhoods of Crown Hill, Green Lake and Phinney Ridge, as well as most of Fremont, North Beach/Blue Ridge, and Wallingford.[3] Ballard is part of the Seattle Public Schools and the Washington State Legislature's 36th legislative district. At the federal level, Ballard is part of the United States House of Representatives's 7th congressional district.

History

editEarly settlement

editThis article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as section. (August 2022) |

The area now called Ballard was settled by the Dxʷdəwʔabš (Duwamish) Tribe after the last glacial period.[4] There were plentiful salmon and clams in the region.[5] The Shilshole area was home to a settlement that has since been excavated; its artifacts are in the collection of the Burke Museum in the University District.[6] According to oral traditions from before European contact, the group living around Shilshole may have been in decline due to a "great catastrophe".[citation needed] The remaining dozen or fewer families were evicted by non-Coast Salish settlers in the mid-19th century. One source suggests that the decline of the Shilshole dwelling Salish might have been due to raids from other groups from farther north (Queen Charlotte's Island) and that these raids also alarmed non-Native settlers.[7] The last member of the Shilshole native group, named HWelch’teed or "Salmon Bay Charlie", was forcibly removed to allow construction of the Hiram Chittenden Locks in 1915 or 1916.[8][9][10]

The first European resident in the area, homesteader Ira Wilcox Utter, moved to his claim in 1853.[5] Utter hoped to see a rapid expansion of population, but when this did not happen, he sold the land to Thomas Burke, a judge.[11] Thirty-six years later, Judge Burke, together with John Leary and railroader Daniel H. Gilman, formed the West Coast Improvement Company to develop Burke's land holdings in the area. They anticipated the building of the Great Northern Railway along the Salmon Bay coastline on the way to Interbay and central Seattle. The partners also built a spur from Fremont's main line of the Seattle, Lake Shore and Eastern Railway. Today three miles (5 km) of this line, running along Salmon Bay from N.W. 40th Street to the BNSF Railway mainline at N.W. 67th, are operated as the Ballard Terminal Railroad.[12]

During the late 19th century Captain William Rankin Ballard, owner of land adjoining Judge Burke's holdings, joined the partnership with Burke, Leary, and Gilman. Then, in 1887 the partnership was dissolved and the assets divided, but no one wanted the land in Salmon Bay so the partners flipped a coin. Capt. Ballard lost the coin-toss and ended up with the "undesirable" 160-acre (0.65 km2) tract.[13]

The railroad to Seattle ended at Salmon Bay because the railroad company was unwilling to build a trestle to cross the bay.[citation needed] From the stop at "Ballard Junction," (as the terminus was called) passengers could walk across the wagon bridge and continue the journey to Seattle. In addition to gaining notoriety as the end of the railway line, the fledgling town of Ballard benefited economically from the railway because the railroad provided a way to bring supplies into the area and also to export locally manufactured products. Ability to ship products spurred the growth of mills of many types. Ballard's first mill, built in 1888 by Mr. J Sinclair was a lumber mill; the second mill, finished the same year was a shingle mill.[14] After the Great Seattle Fire in 1889 the mills provided opportunities for those who had lost jobs in the fire, which in turn spurred the growth of the settlement as families moved north to work in the mills. Ballard experienced an influx of Scandinavian immigrants during this period, and Scandinavian culture and traditions would be influential on Ballard as it developed.[15]

City of Ballard

editWith the rapid population growth, residents realized that there might soon be a need for laws to keep order, a process that would require a formal government. In the late summer of 1889, the community discussed incorporating as a town but eventually rejected the idea of incorporation. The issue pressed, however, and several months later, on November 4, 1889, the residents again voted on the question and this time they voted to incorporate. The first mayor of Ballard was Charles F. Treat.[16] A municipal census, conducted shortly after the passing vote showed that the new town of Ballard had more than 1500 residents, allowing it to be the first "third-class town" to be incorporated in the newly-admitted State of Washington.[17]

By 1900, Ballard's population had grown to 4,568, making it the seventh-largest city in Washington, and the town was faced with many of the problems common to small towns. Saloons had been a problem since the beginning, and in 1904, the drinking and gambling had become so bad that the mayor ordered the City of Ballard officially closed for the day to prevent gambling.[18] The city also faced problems with loose livestock and so the Cow Ordinance of 1903 made allowing cows to graze south of present-day 65th St. a punishable offense. The city faced more serious problems, however, with two of the most difficult being the lack of both a proper water supply and a sewer system. The one weakness of the location on Salmon Bay was the lack of nearby freshwater springs, which meant that water came from local ground water wells. Lack of a proper sewage system contaminated the ground water, compounding the problem.

The town continued to grow and reached 17,000 residents by 1907 to become the second-largest city in King County.[19] However Ballard, like many of the other small cities surrounding Seattle continued to be plagued by water problems.[20][21][18][22][23] The rapid population growth had overwhelmed the city's ability to provide services, particularly safe drinking water and sewers, and Ballard's city government had tried unsuccessfully to deal with the crises. That made the citizens begin to consider asking Seattle to annex the town.[24][25] In 1905, the question was voted on and the residents voted against annexation since they hoped for a solution, but the problems refused to go away.[26] In July 1906, the Supreme Court of Washington ruled that Seattle was not allowed to provide water service to surrounding communities.[27] Ballard had been dependent on a water sharing agreement with Seattle, but the Supreme Court decision left it with inadequate water and forced a second vote on the annexation question. By then, the residents realized the inability of local resources to cope with their situation and the majority of residents voted in favor of annexation. On May 29, 1907 at 3:45 a.m, the City of Ballard officially became part of Seattle.[28][29] On that day, Ballard citizens showed their mixed feelings about the handover by draping their city hall with black crepe and flying the flag at half mast.[28]

Modern history

editDuring the early 20th century, the Ballard area was home to the Ballard shipbuilding company, which produced ships for the US Navy during World War II as well as ships for civilian purposes. The area was also home to a significant number of fisheries and canneries. These marine industries formed the backbone of the Ballard economy for much of the 20th century.[30]

At the end of the 20th century Ballard began to experience a real-estate boom. By early 2007, nearly 20 major apartment/retail projects were under construction or had just been completed within a five-block radius of downtown Ballard. The new developments would add as many as 2500 new households to the neighborhood.[citation needed] This growth in urban density is the result of the neighborhood plan created by former Seattle Mayor Norm Rice. Mayor Rice's plan aimed to reduce suburban sprawl by targeting certain Seattle areas, including Ballard, for high-density development.[citation needed]

Over the years, Ballard has added venues for live music, including bars, restaurants and coffee shops. Each month the Ballard Chamber of Commerce sponsors the Second Saturday Artwalk.[31]

Downtown Ballard is also home to the Majestic Bay Theater, which was the oldest operating movie theater on the West Coast prior to its closure in 1997.[32] In 1998, it was renovated and transformed from a bargain single-screen theater to a well-appointed triplex.[33] Downtown Ballard also boasts a variety of restaurants and local shops.[34] The Deep Sea Fishermen's Union, which represents commercial fishermen, is based in Ballard.[35]

Ballard Historical Society

editThe Ballard Historical Society is a volunteer-run non-profit historical society located in the Ballard neighborhood. The organization does not have any traditional exhibition space, but maintains a community presence through its self-guided historical tours, historical markers, lectures, community events, and collections. The Ballard Historical Society's collections include memorabilia, historical archives, photographs, and other objects relating to Ballard History. The society has made its photo archives available online.[36] The organization has 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status.

Formed in 1988 with encouragement from the Ballard Centennial Committee in celebration of the Washington state centennial in 1989, the organization's establishment coincided with the publication of Passport to Ballard, a collection of essays on the neighborhood's history from pre-European settlement up through the 1980s.[37] In April 2007, the Ballard Historical Society unveiled its Historic Markers, which can be seen on buildings in the Ballard Avenue Historic District.

The organization also co-produced, along with the Nordic Heritage Museum and Swedish-Finn Historical Society, Voices of Ballard: Immigrant Stories from the Vanishing Generation (2001), a book collecting oral histories from long-time Ballard residents who have made the neighborhood home since before the 1960s.[38] The Ballard Walking Tour, a self-guided tour created by the organization, highlights 20 different historic sites on and around Ballard Avenue. The most recent illustrated Tour Brochure was released in February 2009.[39]

Every three years the Ballard Historical Society organizes the Ballard Classic Homes Tour and features a different set of vintage homes in Ballard during each parade of houses.

Culture

editBallard is the traditional center of Seattle's ethnically Scandinavian seafaring community, who were drawn to the area because of the salmon fishing opportunities.[5][40] The neighborhood's unofficial slogan, "Uff da", comes from an Almost Live! sketch that made fun of its Scandinavian culture. In recent years the proportion of Scandinavian residents has decreased but the neighborhood is still proud of its heritage. Ballard is home to the National Nordic Museum, which celebrates both the community of Ballard and the local Scandinavian history. Scandinavians unite in organizations such as the Sons of Norway Leif Ericson Lodge and the Norwegian Ladies Chorus of Seattle. Each year the community celebrates the Ballard SeafoodFest and Norwegian Constitution Day (also called Syttende Mai) on May 17 to commemorate the signing of the Norwegian Constitution.[41]

Locals once nicknamed the neighborhood "Snoose Junction," a reference to the Scandinavian settlers' practice of using snus.[42]

The Majestic Bay Theatre on Market Street is on the same location as the former Bay and Majestic theaters. Before closing for the new construction the Bay Theatre was the longest continuously operating movie theatre on the west coast after the closure of the Cameo in Los Angeles.

The neighborhood is home to a namesake soccer team, Ballard FC, which was founded in 2022 and plays in the fourth-division USL League 2. The semi-professional team is owned by a group led by former Seattle Sounders FC player Lamar Neagle and plays in nearby Interbay at the 1,000-seat Interbay Soccer Stadium.[43]

Schools and libraries

editThe public schools in the neighborhood are part of the citywide Seattle Public Schools district. Ballard High School, located in the neighborhood, is the oldest continuously-operating high school in the city.[44] The original building was demolished in the late 1990s. The new school building is now one of the largest in the district and houses a biotechnology magnet program that attracts students from all over Seattle.[45] The high school has been supported by Amgen, Zymogenetics, G. M. Nameplate, the Youth Maritime Training Association, North Seattle Community College, Seattle City Light, and Swedish Hospital.[46]

There are several elementary schools and one alternative school located in the neighborhood. The closest middle school is Whitman Middle School, which is located north of Ballard in the Crown Hill neighborhood.[47]

- Adams Elementary School (K-5)

- Loyal Heights Elementary School (K-5)

- Matheia School (K-5, private independent)

- North Beach Elementary School (K-5)

- Salmon Bay School (K-8)

- St. Alphonsus School (K-8, Catholic)

- West Woodland Elementary School (K-5)

- Whittier Elementary School (K-5)

The Ballard Public Library was first created as the Carnegie Free Public Library in 1904. In 1907, after annexation, the library became part of the Seattle Public Library system. The original Carnegie building on Market Street was replaced with new construction on 24th Avenue NW in 1963. 42 years later, in 2005, a new library building on 22nd Avenue NW designed by architectural firm Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, was opened as part of the Seattle Public Library's "Libraries for All" initiative.[48] The original Carnegie building on Market Street is a restaurant.

The Seattle Metaphysical Library, originally opened in the Pike Place Market in 1961, is now on Market Street in Ballard, and is open to the public and lends books to members.[49]

Registered historic places

editThe following Ballard buildings, areas and landmarks are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:[50]

| Ballard Avenue Historic District | Along Ballard Avenue N.W. between N.W. Market Street and N.W. Dock Place (added in 1976, ID #76001885). | |

| Ballard Carnegie Library | On N.W. Market Street (added 1979, ID #79002535). | |

| Fire Station No. 18 | At the corner of Russell Avenue N.W. and N.W. Market (added 1973, ID #73001876). | |

| Ballard Bridge | (added 1982, ID #82004231), | |

| Hiram M. Chittenden Locks and the Lake Washington Ship Canal | (added 1978, ID #78002751). |

Notable residents

edit- James Acord – sculpture artist

- Josh Barnett – UFC fighter

- Carl Deuker – young adult sports author

- Tom Douglas – restaurateur

- Jerry Holkins - writer

- Edith Macefield – real-estate holdout

- Dori Monson – radio personality

- Karsten Solheim (1911–2000) – founder of PING golf clubs

References

edit- ^ a b Seattle City Clerk, "Ballard neighborhoods", Geographic Indexing Atlas, The City of Seattle

- ^ Seattle City Clerk, "About the Atlas", Geographic Indexing Atlas, The City of Seattle

- ^ Seattle Department of Neighborhoods, Neighborhoods & Council Districts, The City of Seattle

- ^ "History of the Duwamish People".

- ^ a b c "Ballard: An Important Part of Washington's History". Ballard Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ^ "A story told in stone and wood: The Coast Salish and historic Seattle".

- ^ "Page 69".

- ^ File:Washington edu Salmon Bay Charlie's house at Shilshole w canoe offshore, c 1905, 83.10.9067.jpg

- ^ Dorpat, Paul (October 12, 2003). "The Last to Go". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ Dorpat, Paul (December 19, 2010). "Seattle Now & then: 'Threading the Bead' Between Magnolia and Ballard".

- ^ Reinartz (1988), p. 21.

- ^ "Shippers Team Up to Save Short Line". Railway Age. Vol. 199, no. 6. June 1998. p. 20.

After Burlington Northern and Santa Fe shut down three miles of waterfront line along the Lake Washington Ship Canal in Ballard, Wash., last year, four shippers got together to form the Ballard Terminal Railroad Co. Last month, BRTC was awarded a $350,000 loan by the Washington State Department of Transportation for rehabilitation of the deteriorated track. When that is completed, the new short line will again move such commodities as fish, furniture, sand, cement, and lubrication oil.

- ^ Reinartz (1988), p. 24.

- ^ Wandry, Margret (1975). Four Bridges to Seattle: Old Ballard 1853–1907. Seattle: Ballard Printing & Publishing. p. 79.

- ^ SeattlePI, Levi Pulkkinen (September 27, 2016). "How Ballard became so Scandinavian". seattlepi.com. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ "Seattle Municipal Archives — Annexed Cities — Ballard". Seattle.gov.

- ^ Reinartz (1988), p. 57.

- ^ a b "Would Purchase Municipal Plant". Ballard News. October 12, 1901.

- ^ Bass, Sophie (1947). When Seattle Was a Village. Seattle: Lowman & Hanford. p. 116.

- ^ "The Water Situation". Ballard News. April 6, 1901.

- ^ "Notice to Water Consumers". Ballard News. July 6, 1901.

- ^ "New Well Connected Up". Ballard News. July 6, 2007.

- ^ "New Pump Connected Up". Ballard News. July 13, 2007.

- ^ "Annexation Cause is Gaining Ground". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. November 9, 1905.

- ^ "Enthusiasm Shown for Annexation". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. November 11, 1905.

- ^ "Ballard Votes to Go At It Alone". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. November 6, 1905.

- ^ "Will Allow Use of City Water". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. July 20, 1906.

- ^ a b Reinartz (1988), p. 64.

- ^ "Ballard Is Now Part of Seattle". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. May 30, 1907.

- ^ "The History of Ballard: The First 100 Years | Filson Journal". The Filson Journal. December 30, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ "Second Saturday Artwalk". inballard.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ Pastier, John (October 11, 2000). "Triple feature". The Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ "About The Bay". Majestic Bay Theatres. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ "Boutique Shops, Neighborhood Pubs, Eclectic Restaurants, and Waterfront Parks in Ballard". inballard.com. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ "Deep Sea Fishermen's Union". Filson. January 21, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ "Letter from the President". Ballard Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 9, 2007.

- ^ Reinartz, Kay F, ed. (1988). Passport to Ballard: the Centennial Story. Seattle: Ballard News Tribune.

- ^ Marianne Forssblad. "Abstract: The Vanishing Generation: An Oral History Project". Pacific Northwest Historian Guild. Archived from the original on May 28, 2005.

- ^ Wong, Dean (August 10, 2005). "Historical Society announces new tour". Ballard News-Tribune. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011.

- ^ "17th of May Celebration in Seattle". Norwegian 17th of May Committee. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Walt Crowley (March 31, 1999). "Seattle Neighborhoods: Ballard – Thumbnail History". HistoryLink.org.

- ^ Evans, Jayda (May 21, 2022). "Ballard FC kicks off its existence with passionate fan base already installed and an easy win". The Seattle Times. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ "History of Fremont". Rockwell Realty, LLC. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ "Biotech Academy". Ballard High School. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- ^ "Ballard High School 2007 Annual Report" (PDF). Seattle Public Schools. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2008. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ "Seattle Public Schools – Northwest Region". Seattle Public Schools. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ "About the Ballard Branch". The Seattle Public Library. Archived from the original on October 22, 2008. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ Allison, Espiritu (March 20, 2009). "Book worms offer alternative ideas through Seattle Metaphysical Library". Ballard News-Tribune. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ "Washington — King County". National Register of Historic Places. page 1. Retrieved September 16, 2007. page 2