Alliance 90/The Greens (German: Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, pronounced [ˈbʏntnɪs ˈnɔʏntsɪç diː ˈɡʁyːnən] ), often simply referred to as Greens[a] (Grüne, pronounced [ˈɡʁyːnə] ), is a green political party in Germany.[3] It was formed in 1993 by the merger of the Greens (formed in West Germany in 1980) and Alliance 90 (formed in East Germany in 1990). The Greens had itself merged with the East German Green Party after German reunification in 1990.[4]

Alliance 90/The Greens Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Co-Leaders | |

| Parliamentary leaders | |

| Founded |

|

| Merger of |

|

| Headquarters | Platz vor dem Neuen Tor 1 10115 Berlin |

| Youth wing | Green Youth |

| Membership (March 2024) | |

| Ideology | Green politics Social liberalism |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| European affiliation | European Green Party |

| European Parliament group | Greens/EFA |

| International affiliation | Global Greens |

| Colours | Green |

| Bundestag | 117 / 733 |

| Bundesrat | 12 / 69 |

| State Parliaments | 320 / 1,894 |

| European Parliament | 12 / 96 |

| Heads of State Governments | 1 / 16 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

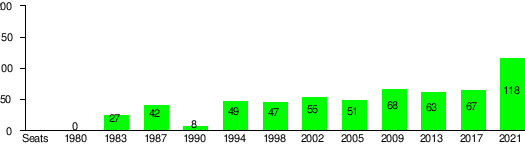

Since January 2022, Ricarda Lang and Omid Nouripour have been co-leaders of the party. It currently holds 118 of the 736 seats in the Bundestag, having won 14.8% of votes cast in the 2021 federal election, and its parliamentary group is the third largest of six. Its parliamentary co-leaders are Britta Haßelmann and Katharina Dröge. The Greens have been part of the federal government twice: first as a junior partner to the Social Democrats (SPD) from 1998 to 2005, and then with the SPD and the Free Democratic Party (FDP) in the traffic light coalition since the 2021 German federal election. In the incumbent Scholz cabinet, the Greens have five ministers, including Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck and Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock.

The party holds seats in all of Germany's state legislatures, except the Saarland, and is a member of coalition governments in eleven states. Winfried Kretschmann, Minister-President of Baden-Württemberg, is the only Green head of government in Germany. The Landtag of Baden-Württemberg is also the only state legislature in which Alliance 90/The Greens is the largest party; it is the second largest party in the legislatures of Berlin, Hamburg, and Schleswig-Holstein.

Alliance 90/The Greens is a founding member of the European Green Party and the Greens–European Free Alliance group in the European Parliament. It is currently the largest party in the G/EFA group, with 21 MEPs. In the 2019 European election, Alliance 90/The Greens was the second largest party in Germany, winning 20.5% of votes cast. The party had 126,451 members in December 2022, making it the fourth largest party in Germany by membership.[5]

History

editBackground

editThe Green Party was initially founded in West Germany as Die Grünen (the Greens) in January 1980. It grew out of the anti-nuclear energy, environmental, peace, new left, and new social movements of the late 20th century.[6]

Grüne Liste Umweltschutz (green list for environmental protection) was the name used for some branches in Lower Saxony and other states in the Federal Republic of Germany. These groups were founded in 1977 and took part in several elections. Most of them merged with The Greens in 1980.

The West Berlin state branch of The Greens was founded as Alternative Liste, or precisely, Alternative Liste für Demokratie und Umweltschutz (AL; alternative list for democracy and environmental protection) in 1978 and became the official West Berlin branch of The Greens in 1980. In 1993, it renamed to Alliance 90/The Greens Berlin after the merger with East Berlin's Greens and Alliance 90.

The Hamburg state branch of the Green Party was called Grün-Alternative Liste Hamburg (GAL; green-alternative list) from its foundation in 1982 until 2012. In 1984, it became the official Hamburg branch of The Greens.

12–13 January 1980: Foundation congress

editThe political party The Greens (German: Die Grünen) sprung out of the wave of New Social Movements that were active in the 1970s, including environmentalist, anti-war, and anti-nuclear movements which can trace their origin to the student protests of 1968. Officially founded as a German national party on 13 January 1980 in Karlsruhe, the party sought to give these movements political and parliamentary representation, as the pre-existing peoples parties were not organised in a way to address their stated issues.[7] Its membership included organisers from former attempts to achieve institutional representation such as GLU and AUD. Opposition to pollution, use of nuclear power, NATO military action, and certain aspects of industrialised society were principal campaign issues.[citation needed] The party also championed sexual liberation and some of their members supported the abolition of age of consent laws.[8]

The formation of a party was purportedly first discussed by movement leaders in 1978. Important figures in the first years were – among others – Petra Kelly, Joschka Fischer, Gert Bastian, Lukas Beckmann, Rudolf Bahro, Joseph Beuys, Antje Vollmer, Herbert Gruhl, August Haußleiter, Luise Rinser, Dirk Schneider, Christian Ströbele, Jutta Ditfurth, Baldur Springmann and Werner Vogel.

In the foundational congress of 1980, the ideological tenets of the party were consolidated, proclaiming the famous Four Pillars of the Green Party:

1980s: Parliamentary representation on the federal level

editIn 1982, the conservative factions of the Greens broke away to form the Ecological Democratic Party (ÖDP). Those who remained in the Green party were more strongly pacifist and against restrictions on immigration and reproductive rights, while supporting the legalisation of cannabis use, placing a higher priority on working for LGBT rights, and tending to advocate what they described as "anti-authoritarian" concepts of education and child-rearing. They also tended to identify more closely with a culture of protest and civil disobedience, frequently clashing with police at demonstrations against nuclear weapons, nuclear energy, and the construction of a new runway (Startbahn West) at Frankfurt Airport. Those who left the party at the time might have felt similarly about some of these issues, but did not identify with the forms of protest that Green party members took part in.[citation needed]

After some success at state-level elections, the party won 27 seats with 5.7% of the vote in the Bundestag, the lower house of the German parliament, in the 1983 federal election. Among the important political issues at the time was the deployment of Pershing II IRBMs and nuclear-tipped cruise missiles by the U.S. and NATO on West German soil, generating strong opposition in the general population that found an outlet in mass demonstrations. The newly formed party was able to draw on this popular movement to recruit support. Partly due to the impact of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, and to growing awareness of the threat of air pollution and acid rain to German forests (Waldsterben), the Greens increased their share of the vote to 8.3% in the 1987 federal election. Around this time, Joschka Fischer emerged as the unofficial leader of the party, which he remained until resigning all leadership posts following the 2005 federal election.

The Greens were the target of attempts by the East German secret police to enlist the cooperation of members who were willing to align the party with the agenda of the German Democratic Republic. The party ranks included several politicians who were later discovered to have been Stasi agents, including Bundestag representative Dirk Schneider, European Parliament representative Brigitte Heinrich, and Red Army Faction defense lawyer Klaus Croissant. Greens politician and Bundestag representative Gert Bastian was also a founding member of Generals for Peace, a pacifist group created and funded by the Stasi, the revelation of which may have contributed to the murder-suicide in which he killed his partner and Greens founder Petra Kelly.[9] A study commissioned by the Greens determined that 15 to 20 members intimately cooperated with the Stasi and another 450 to 500 had been informants.[10][11]

Until 1987, the Greens included a faction involved in pedophile activism, the SchwuP short for Arbeitsgemeinschaft "Schwule, Päderasten und Transsexuelle" (approx. working group "Gays, Pederasts and Transsexuals"). This faction campaigned for repealing § 176 of the German penal code, dealing with child sexual abuse. This group was controversial within the party itself, and was seen as partly responsible for the poor election result of 1985.[12] This controversy re-surfaced in 2013 and chairwoman Claudia Roth stated she welcomed an independent scientific investigation on the extent of influence pedophile activists had on the party in the mid-1980s.[13][14] In November 2014, the political scientist Franz Walter presented the final report about his research on a press conference.[15]

1990s: German reunification, electoral failure in the West, formation of Alliance 90/The Greens

editIn the 1990 federal elections, taking place post-reunified Germany, the Greens in the West did not pass the 5% limit required to win seats in the Bundestag. It was only due to a temporary modification of German election law, applying the five-percent "hurdle" separately in East and West Germany, that the Greens acquired any parliamentary seats at all. This happened because in the new states of Germany, the Greens, in a joint effort with Alliance 90, a heterogeneous grouping of civil rights activists, were able to gain more than 5% of the vote. Some critics attribute this poor performance to the reluctance of the campaign to cater to the prevalent mood of nationalism, instead focusing on subjects such as global warming. A campaign poster at the time proudly stated, "Everyone is talking about Germany; we're talking about the weather!", paraphrasing a popular slogan of Deutsche Bundesbahn, the German national railway. The party also opposed imminent reunification that was in process, instead wanting to initiate debates on ecology and nuclear issues before reunification causing a drop in support in Western Germany.[16] After the 1994 federal election; however, the merged party returned to the Bundestag, and the Greens received 7.3% of the vote nationwide and 49 seats.

1998–2002: Greens as governing party, first term

editIn the 1998 federal election, despite a slight fall in their percentage of the vote (6.7%), the Greens retained 47 seats and joined the federal government for the first time in 'Red-Green' coalition government with the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Joschka Fischer became Vice-Chancellor of Germany and foreign minister in the new government, which had two other Green ministers (Andrea Fischer, later Renate Künast, and Jürgen Trittin).

Almost immediately the party was plunged into a crisis by the question of German participation in the NATO actions in Kosovo. Numerous anti-war party members resigned their party membership when the first post-war deployment of German troops in a military conflict abroad occurred under a Red-Green government, and the party began to experience a long string of defeats in local and state-level elections. Disappointment with the Green participation in government increased when anti-nuclear power activists realised that shutting down the nation's nuclear power stations would not happen as quickly as they wished, and numerous pro-business SPD members of the federal cabinet opposed the environmentalist agenda of the Greens, calling for tacit compromises.

In 2001, the party experienced a further crisis as some Green Members of Parliament refused to back the government's plan of sending military personnel to help with the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. Chancellor Gerhard Schröder called a vote of confidence, tying it to his strategy on the war. Four Green MPs and one Social Democrat voted against the government, but Schröder was still able to command a majority.

On the other hand, the Greens achieved a major success as a governing party through the 2000 decision to phase out the use of nuclear energy. Minister of Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety Jürgen Trittin reached an agreement with energy companies on the gradual phasing out of the country's nineteen nuclear power plants and a cessation of civil usage of nuclear power by 2020. This was authorised through the Nuclear Exit Law. Based on an estimate of 32 years as the normal period of operation for a nuclear power plant, the agreement defines precisely how much energy a power plant is allowed to produce before being shut down. This law has since been overturned.

2002–2005: Greens as governing party, second term

editDespite the crises of the preceding electoral period, in the 2002 federal election, the Greens increased their total to 55 seats (in a smaller parliament) and 8.6%. This was partly due to the perception that the internal debate over the war in Afghanistan had been more honest and open than in other parties, and one of the MPs who had voted against the Afghanistan deployment, Hans-Christian Ströbele, was directly elected to the Bundestag as a district representative for the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg – Prenzlauer Berg East constituency in Berlin, becoming the first Green to ever gain a first-past-the-post seat in Germany.

The Greens benefited from increased inroads among traditionally left-wing demographics which had benefited from Green-initiated legislation in the 1998–2002 term, such as environmentalists (Renewable Energies Act) and LGBT groups (Registered Partnership Law). Perhaps most important for determining the success of both the Greens and the SPD was the increasing threat of war in Iraq, which was highly unpopular with the German public, and helped gather votes for the parties which had taken a stand against participation in this war. Despite losses for the SPD, the Red-Green coalition government retained a very slight majority in the Bundestag (4 seats) and was renewed, with Joschka Fischer as foreign minister, Renate Künast as minister for consumer protection, nutrition and agriculture, and Jürgen Trittin as minister for the environment.

One internal issue in 2002 was the failed attempt to settle a long-standing discussion about the question of whether members of parliament should be allowed to become members of the party executive. Two party conventions declined to change the party statute. The necessary majority of two-thirds was missed by a small margin. As a result, former party chairpersons Fritz Kuhn and Claudia Roth (who had been elected to parliament that year) were no longer able to continue in their executive function and were replaced by former party secretary general Reinhard Bütikofer and former Bundestag member Angelika Beer. The party then held a member referendum on this question in the spring of 2003 which changed the party statute. Now members of parliament may be elected for two of the six seats of the party executive, as long as they are not ministers or caucus leaders. 57% of all party members voted in the member referendum, with 67% voting in favor of the change. The referendum was only the second in the history of Alliance 90/The Greens, the first having been held about the merger of the Greens and Alliance 90. In 2004, after Angelika Beer was elected to the European Parliament, Claudia Roth was elected to replace her as party chair.

The only party convention in 2003 was planned for November 2003, but about 20% of the local organisations forced the federal party to hold a special party convention in Cottbus early to discuss the party position regarding Agenda 2010, a major reform of the German welfare programmes planned by Chancellor Schröder.

The November 2003 party convention was held in Dresden and decided the election platform for the 2004 European Parliament elections. The German Green list for these elections was headed by Rebecca Harms (then leader of the Green party in Lower Saxony) and Daniel Cohn-Bendit, previously Member of the European Parliament for The Greens of France. The November 2003 convention is also noteworthy because it was the first convention of a German political party ever to use an electronic voting system.

The Greens gained a record 13 of Germany's 99 seats in these elections, mainly due to the perceived competence of Green ministers in the federal government and the unpopularity of the Social Democratic Party.

In early 2005, the Greens were the target of the German Visa Affair 2005, instigated in the media by the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). At the end of April 2005, they celebrated the decommissioning of the Obrigheim nuclear power station. They also continue to support a bill for an Anti-Discrimination Law (Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz) in the Bundestag.

In May 2005, the only remaining state-level red-green coalition government lost the vote in the North Rhine-Westphalia state election, leaving only the federal government with participation of the Greens (apart from local governments). In the early 2005 federal election the party incurred very small losses and achieved 8.1% of the vote and 51 seats. However, due to larger losses of the SPD, the previous coalition no longer had a majority in the Bundestag.

2005–2021: In opposition

editFor almost two years after the federal election in 2005, the Greens were not part of any government at the state or federal level. In June 2007, the Greens in Bremen entered into a coalition with the Social Democratic Party (SPD) following the 2007 Bremen state election.

In April 2008, following the 2008 Hamburg state election, the Green-Alternative List (GAL) in Hamburg entered into a coalition with the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the first such state-level coalition in Germany. Although the GAL had to agree to the deepening of the Elbe River, the construction of a new coal-fired power station and two road projects they had opposed, they also received some significant concessions from the CDU. These included reforming state schools by increasing the number of primary school educational stages, the restoration of trams as public transportation in the city-state, and more pedestrian-friendly real estate development. On 29 November 2010, the coalition collapsed, resulting in an election that was won by SPD.

Following the Saarland state election of August 2009, The Greens held the balance of power after a close election where no two-party coalitions could create a stable majority government. After negotiations, the Saarland Greens rejected the option of a left-wing 'red-red-green' coalition with the SPD and The Left (Die Linke) in order to form a centre-right state government with the CDU and Free Democratic Party (FDP), a historical first time that a Jamaica coalition has formed in German politics.

In June 2010, in the first state election following the victory of the CDU/CSU and FDP in the 2009 federal election, the "black-yellow" CDU-FDP coalition in North Rhine-Westphalia under Jürgen Rüttgers lost its majority. The Greens and the SPD came one seat short of a governing majority, but after multiple negotiations about coalitions of SPD and Greens with either the FDP or The Left, the SPD and Greens decided to form a minority government,[17] which was possible because under the constitution of North Rhine-Westphalia a plurality of seats is sufficient to elect a minister-president.[18] So a red-green government in a state where it was defeated under Peer Steinbrück in 2005 came into office again on 14 June 2010 with the election of Hannelore Kraft as minister-president (Cabinet Kraft I).

The Greens founded the first international chapter of a German political party in the U.S. on 13 April 2008 at the Goethe-Institut in Washington D.C. Its main goal is "to provide a platform for politically active and green-oriented German citizens, in and beyond Washington D.C., to discuss and actively participate in German Green politics. [...] to foster professional and personal exchange, channeling the outcomes towards the political discourse in Germany."[19]

In March 2011 (two weeks after the Fukushima nuclear disaster had begun), the Greens made large gains in Rhineland-Palatinate and in Baden-Württemberg. In Baden-Württemberg they became the senior partner in a governing coalition for the first time. Winfried Kretschmann is now the first Green to serve as Minister-President of a German State (Cabinet Kretschmann I and II). Polling data from August 2011 indicated that one in five Germans supported the Greens.[20] From 4 October 2011 to 4 September 2016, the party was represented in all state parliaments.

Like the Social Democrats, the Greens backed Chancellor Angela Merkel on most bailout votes in the German parliament during her second term, saying their pro-European stances overrode party politics.[21] Shortly before the elections, the party plummeted to a four-year low in the polls, undermining efforts by Peer Steinbrück's Social Democrats to unseat Merkel.[22] While being in opposition on the federal level since 2005, the Greens have established themselves as a powerful force in Germany's political system. By 2016, the Greens had joined 11 out of 16 state governments in a variety of coalitions.[23] Over the years, they have built up an informal structure called G-coordination to organize interests between the federal party office, the parliamentary group in the Bundestag, and the Greens governing on the state level.[23]

The Greens remained the smallest of six parties in the Bundestag in the 2017 federal election, winning 8.9% of votes. After the election, they entered into talks for a Jamaica coalition with the CDU and FDP. Discussions collapsed after the FDP withdrew in November.[24][25]

After the federal election and unsuccessful Jamaica negotiations, the party held elections for two new co-leaders; incumbents Özdemir and Peter did not stand for re-election. Robert Habeck and Annalena Baerbock were elected with 81% and 64% of votes, respectively. Habeck had served as deputy premier and environment minister in Schleswig-Holstein since 2012, while Baerbock had been a leading figure in the party's Brandenburg branch since 2009. Their election was considered a break with tradition, as they were both members of the moderate wing.[26]

The Greens saw a major surge in support during the Bavarian and Hessian state elections in October 2018, becoming the second largest party in both.[27][28] They subsequently rose to second place behind the CDU/CSU in national polling, averaging between 17% and 20% over the next six months.[29]

In the 2019 European Parliament election, the Greens achieved their best ever result in a national election, placing second with 20.5% of the vote and winning 21 seats.[30] National polling released after the election showed a major boost for the party. The first poll after the election, conducted by Forsa, showed the Greens in first place on 27%. This was the first time the Greens had ever been in first place in a national opinion poll, and the first time in the history of the Federal Republic that any party other than the CDU/CSU or SPD had placed first in a national poll.[31] This trend continued as polls from May to July showed the CDU/CSU and Greens trading first place, after which point the CDU/CSU pulled ahead once more. The Greens continued to poll in the low 20% range into early 2020.[29]

The Greens recorded best-ever results in the Brandenburg (10.8%) and Saxony (8.6%) state elections in September 2019, and subsequently joined coalition governments in both states.[32][33] They suffered an unexpected decline in the Thuringian election in October, only narrowing retaining their seats with 5.2%. In the February 2020 Hamburg state election, the Greens became the second largest party, winning 24.2% of votes cast.[34]

In March 2021, the Greens improved their performance in Baden-Württemberg, where they remained the strongest party with 32.6% of votes, and Rhineland-Palatinate, where they moved into third place with 9.3%.[35][36]

Due to their sustained position as the second most popular party in national polling ahead of the September 2021 federal election, the Greens chose to forgo the traditional dual lead-candidacy in favour of selecting a single Chancellor candidate.[37] Co-leader Annalena Baerbock was announced as Chancellor candidate on 19 April[38] and formally confirmed on 12 June with 98.5% approval.[39]

The Greens surged in opinion polls in late April and May, briefly surpassing the CDU as the most popular party in the country, but their numbers slipped back after Baerbock was caught up in several controversies. Her personal popularity also fell below that of both Armin Laschet and Olaf Scholz, the Chancellor candidates for the CDU and SPD, respectively. The party's fortunes did not reverse even after the July floods, which saw climate change return as the most important issue among voters.[40] The situation worsened in August as the SPD surged into first place to the detriment of both the CDU and Greens.[41]

2021–present: Return to government

editThe Greens finished in third place in the 2021 federal election with 14.8% of votes. Though their best ever federal election result, it was considered a bitter disappointment in light of their polling numbers during the previous three years.[42] They entered coalition talks with the FDP and SPD, eventually joining a traffic light coalition under Chancellor Olaf Scholz which took office on 8 December 2021.[43] The Greens have five ministers in the Scholz cabinet, including Robert Habeck as Vice-Chancellor and Annalena Baerbock as foreign minister.[44]

Since party statute mandates that party leaders may not hold government office, Baerbock and Habeck stepped down after entering cabinet. At a party conference in January 2022, Ricarda Lang and Omid Nouripour were elected to succeed them. At the time of her election, Lang was 28 years old, speaker for women's issues, and a former leader of the Green Youth. 46-year-old Nouripour was foreign affairs spokesman and a member of the Bundestag since 2006. Of the new leaders, Lang is considered a representative of the party's left-wing, while Nouripour represents the right-wing.[45][46]

Lang and Nouripour announced their resignations as party leaders in September 2024 after heavy defeats in the Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg state elections that month. In all three states, governing coalitions involving the Greens were not returned, and the party was wiped out in the latter two states while only narrowly retaining representation in Saxony. The party had fallen out of five state governments (additionally Berlin and Hesse) since entering the federal governing coalition in 2021. Analysts pointed to its participation in the federal government requiring it to take stances that are contrary to its traditional clean-energy and pacifist ideals, as well as a stark collapse in support with young voters. Lang and Nouripour remain in office until successors are elected in November.[47][48]

Ideology and platform

editThe party's main ideological trends are green politics[3] and social liberalism.[49][50] The party has also been described as left-libertarian[51] and influenced by the postmaterialist left.[52][53] The party's political position is generally described to be centre-left,[54][55] but there are also journalistic sources describing the party as centrist.[56][57][58][59] The West German Greens played a crucial role in the development of green politics in Europe,[60] with their original program outlining "four principles: ecological, social, grassroots, and non-violent."[61] Initially ideologically heterogenous, the party took up a position on the radical left in its early years, which were dominated by conflicts between the more left-wing "Fundi" (fundamentalist) and more moderate "Realo" (realist) factions. These conflicts became less significant as the party moved toward the political mainstream in the 1990s.[54]

During the 2021 federal election, the WZB Berlin Social Science Center classified the party as the most centrist of Germany's left-wing parties.[62] However, Baerbock campaigned from the left of the SPD, stating that the party's economic program is geared towards the "common good" while the SPD's no longer is.[63] The party has a more pragmatic approach to workers' rights than the SPD.[54][55][62] On the other hand, the party clearly holds positions to the left of the SPD on issues such as fiscal discipline,[64] particularly on the debt brake,[65] the climate transition,[66] and property expropriation in Berlin.[67] They are focusing on environmentalist and socially progressive policies.[68] Emphasis is placed on mitigating climate change, reducing carbon emissions, and fostering sustainability and environmentally-friendly practices.[69] They support equality, social justice, and humanitarian responses to events such as the European migrant crisis.[70] Their fiscal platform is flexible and seeks to balance social, economic, and environmental interests.[71] The party is strongly pro-European, advocating European federalism,[72] and promotes wider international cooperation, including strengthening existing alliances.[71]

Starting from the leadership of Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck, commentators have observed the Greens taking a pragmatic, moderate approach to work with parties from across the political spectrum. Baerbock described their stances and style as a form of "radical realism" attempting to reconcile principles with practical politics.[71][73] At the same time, the party has denounced populism and division, and placed rhetorical emphasis on optimism and cross-party cooperation.[54][74] Accompanied by record high popularity and election results, this led some to suggest that the Greens were filling a gap in the political centre, which was left by the declining popularity of the CDU/CSU and SPD.[54][68]

Economic policies

editThe party has economically left-liberal views.[49]

Foreign policy

editThe Greens are regarded as taking a Atlanticist line on defense and pushing for a stronger common EU foreign policy,[75] especially against Russia and China.[76][77] Green Party co-leader Annalena Baerbock has proposed a post-pacifist foreign policy.[78][79] She supports eastward expansion of NATO[76] and has considered the number of UN resolutions critical of Israel as "absurd compared to resolutions against other states."[80] The party's program included references to NATO as an "indispensable" part of European security.[81] The Greens have promised to abolish the contested Nord Stream 2 pipeline to ship Russian natural gas to Germany.[82] The party criticized the EU's investment deal with China.[83] In 2016, the Greens criticised Germany's defense plan with Saudi Arabia, which has been waging war in Yemen and has been accused of massive human rights violations.[84]

The party remains divided over issues such as nuclear disarmament and U.S. nuclear weapons on German territory. Some Greens want Germany to sign the United Nations' Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[85][86][87]

About the Israel-Hamas War, the Federal Minister of Food and Agriculture Cem Özdemir (former president of the party) criticized Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg for her presence and support of pro-Palestinian demonstrations in Berlin, calling on everyone to reconsider their opinions about her.[88][89]

Energy and nuclear power

editEver since the party's inception, The Greens have been concerned with the immediate halt of construction or operation of all nuclear power stations. As an alternative, they promote a shift to non-nuclear renewable energy and a comprehensive program of energy conservation.[90]

In 1986, large parts of Germany were covered with radioactive contamination from the Chernobyl disaster and Germans went to great lengths to deal with the contamination. Germany's anti-nuclear stance was strengthened. From the mid-1990s onwards, anti-nuclear protests were primarily directed against transports of radioactive waste in "CASTOR" containers.

After the Chernobyl disaster, the Greens became more radicalised and resisted compromise on the nuclear issue. During the 1990s, a re-orientation towards a moderate program occurred, with concern about global warming and ozone depletion taking a more prominent role. During the federal red-green government (1998–2005) many people[who?] became disappointed with what they saw as excessive compromise on key Greens policies.

Environment and climate policy

editThe central idea of green politics is sustainable development.[92] The concept of environmental protection is the cornerstone of Alliance 90/The Greens policy. In particular, the economic, energy and transport policy claims are in close interaction with environmental considerations. The Greens acknowledge the natural environment as a high priority and animal protection should be enshrined as a national objective in constitutional law. An effective environmental policy would be based on a common environmental code, with the urgent integration of a climate change bill. During the red-green coalition (1998–2005) a policy of agricultural change was launched labeled as a paradigm shift in agricultural policy towards a more ecological friendly agriculture, which needs to continue.

The Greens have praised the European Green Deal, which aims to make the EU climate neutral by 2050. Climate change is at the center of all policy considerations. This includes environmental policy and safety and social aspects. The plans of the Alliance 90/The Greens provide a climate change bill laying down binding reductions to greenhouse gas emissions in Germany by 2020 restricting emissions to minus 40 percent compared to 1990.

European Union

editAlliance 90/The Greens supports the eventual federalization of the European Union into a Federal European Republic (German: Föderale Europäische Republik), i.e. a single federal European sovereign state.[72][93]

Transport

editA similarly high priority is given to transport policy. The switch from a traveling allowance to a mobility allowance, which is paid regardless of income to all employees, replacing company car privileges. The truck toll will act as a climate protection instrument internalizing the external costs of transport. Railway should be promoted in order to achieve the desired environmental objectives and the comprehensive care of customers. The railway infrastructure is to remain permanently in the public sector, allowing a reduction in expenditure on road construction infrastructure. The Greens want to control privileges on kerosene and for international flights, introduce an air ticket levy.

Fossil fuels such as heavy oil or diesel shall be replaced by emission-neutral fuels and green propulsion systems in order to make shipping climate-neutral in the long term.[94]

Social policy

editFor many years, the Green Party has advocated against the "Ehegattensplitting" policy, under which the incomes of married couples are split for taxation purposes. Furthermore, the Party advocates for a massive increase in federal spending for places in preschools, and for increased investment in education: an additional 1 billion Euros for vocational schools and 200 million Euros more BAföG (Bundesausbildungsförderungsgesetz in German, approximately translated to "the Federal Law for the Advancement of Education") for adults.[95]

In its 2013 platform, the Green Party successfully advocated for a minimum wage of 8.50 Euro per hour, which was implemented on 1 January 2015.[96] It continues to press for higher minimum wages.[97]

The Greens want the starting retirement age to remain 67,[98] but with some qualifications – for example, a provision for partial retirement.[citation needed][99]

The party supports and has supported various forms of rent regulation.[100] During the 2021 election, the party called for rent hikes to be capped at 2.5% per year.[101]

The Greens support progressive taxation and is critical of FDP efforts to cut taxes for top earners.[102]

Women and LGBTQIA+ rights

editThe Green Party supports the implementation of quotas in executive boards, the policy of equal pay for equal work, and continuing the fight against domestic violence.[103] According to its website, the Green Party "fights for the acceptance and against the exclusion of homosexuals, bisexuals, intersex- and transgender people and others".[104]

In order to recognize the political persecution that LGBT+ people face abroad, the Green Party wants to extend asylum to LGBTQIA+ people abroad.[105] The policy change was sponsored primarily by Volker Beck, one of the Party's most prominent gay members.[106] Because of the extensive support the Green Party has given the LGBTQIA+ community since its conception, many LGBTQIA+ people vote for the Green Party even if their political ideology does not quite align otherwise.[106]

Drug policy

editThe party supports the legalization and regulation of cannabis and is the sponsor of the proposed German cannabis control bill.

Furthermore, the Greens support research on the drug and the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes.[107][108]

Electorate

editA 2000 study by the Infratest Dimap political research company has suggested the Green voter demographic includes those on higher incomes (e.g. above €2000/month) and the party's support is less among households with lower incomes. The same polling research also concluded that the Greens received fewer votes from the unemployed and general working population, with business people favouring the party as well as the centre-right liberal Free Democratic Party. According to Infratest Dimap the Greens received more voters from the age group 34–42 than any other age group and that the young were generally more supportive of the party than the old. (Source: Intrafest Dimap political research company for the ARD.[109])

The Greens have a higher voter demographic in urban areas than rural areas, except for a small number of rural areas with pressing local environmental concerns, such as strip mining or radioactive waste deposits. The cities of Bonn, Cologne, Stuttgart, Berlin, Hamburg, Frankfurt and Munich have among the highest percentages of Green voters in the country. The towns of Aachen, Bonn, Darmstadt, Hanover, Mönchengladbach and Wuppertal have Green mayors. The party has a lower level of support in the states of the former German Democratic Republic (East Germany); nonetheless, the party is currently represented in every state landtag except Saarland.

Election results

editFederal Parliament (Bundestag)

edit| Election | Constituency | Party list | Seats | +/– | Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||

| 1980 | 732,619 | 1.0 (#5) | 569,589 | 1.5 (#5) | 0 / 497

|

No seats | |

| 1983 | 1,609,855 | 4.1 (#5) | 2,167,431 | 5.6 (#5) | 27 / 498

|

27 | Opposition |

| 1987 | 2,649,459 | 7.0 (#4) | 3,126,256 | 8.3 (#5) | 42 / 497

|

15 | Opposition |

| 1990[a] | 2,589,912 | 5.6 (#5) | 2,347,407 | 5.0 (#4) | 8 / 662

|

36 | Opposition |

| 1994 | 3,037,902 | 6.5 (#4) | 3,424,315 | 7.3 (#4) | 49 / 672

|

41 | Opposition |

| 1998 | 2,448,162 | 5.0 (#4) | 3,301,624 | 6.7 (#4) | 47 / 669

|

2 | SPD–Greens |

| 2002 | 2,693,794 | 5.6 (#5) | 4,108,314 | 8.6 (#4) | 55 / 603

|

8 | SPD–Greens |

| 2005 | 2,538,913 | 5.4 (#5) | 3,838,326 | 8.1 (#5) | 51 / 614

|

4 | Opposition |

| 2009 | 3,974,803 | 9.2 (#5) | 4,641,197 | 10.7 (#5) | 68 / 622

|

17 | Opposition |

| 2013 | 3,177,269 | 7.3 (#5) | 3,690,314 | 8.4 (#4) | 63 / 630

|

5 | Opposition |

| 2017 | 3,717,436 | 8.0 (#6) | 4,157,564 | 8.9 (#6) | 67 / 709

|

4 | Opposition |

| 2021 | 6,465,502 | 14.0 (#3) | 6,848,215 | 14.7 (#3) | 118 / 735

|

51 | SPD–Greens–FDP (2021–2024) |

| SPD–Greens (2024–present) | |||||||

a Results of Alliance 90/The Greens (East) and The Greens (West)

European Parliament

edit| Election | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | EP Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 893,683 | 3.21 (#5) | 0 / 81

|

New | – |

| 1984 | 2,025,972 | 8.15 (#4) | 7 / 81

|

7 | RBW |

| 1989 | 2,382,102 | 8.45 (#3) | 8 / 81

|

1 | G |

| 1994 | 3,563,268 | 10.06 (#3) | 12 / 99

|

4 | |

| 1999 | 1,741,494 | 6.44 (#4) | 7 / 99

|

5 | Greens/EFA |

| 2004 | 3,078,276 | 11.94 (#3) | 13 / 99

|

6 | |

| 2009 | 3,193,821 | 12.13 (#3) | 14 / 99

|

1 | |

| 2014 | 3,138,201 | 10.69 (#3) | 11 / 96

|

3 | |

| 2019 | 7,675,584 | 20.53 (#2) | 21 / 96

|

10 | |

| 2024 | 4,736,913 | 11.90 (#4) | 12 / 96

|

9 |

State Parliaments (Länder)

edit| State parliament | Election | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | 2021 | 1,585,903 | 32.6 (#1) | 58 / 154

|

11 | Greens–CDU |

| Bavaria | 2023 | 1,972,147 | 14.4 (#4) | 32 / 205

|

6 | Opposition |

| Berlin | 2023 | 278,964 | 18.4 (#3) | 34 / 159

|

2 | Opposition |

| Brandenburg | 2024 | 62,031 | 4.1 (#4) | 0 / 88

|

10 | No seats |

| Bremen | 2023 | 150,263 | 11.9 (#3) | 11 / 84

|

5 | SPD–Greens–Left |

| Hamburg | 2020 | 963,796 | 24.2 (#2) | 33 / 123

|

18 | SPD–Greens |

| Hesse | 2023 | 415,888 | 14.8 (#4) | 22 / 137

|

7 | Opposition |

| Lower Saxony | 2022 | 526,923 | 14.5 (#3) | 24 / 146

|

12 | SPD–Greens |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 2021 | 57,548 | 6.8 (#5) | 5 / 79

|

5 | Opposition |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 2022 | 1,299,821 | 18.2 (#3) | 39 / 195

|

25 | CDU–Greens |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 2021 | 179,902 | 9.3 (#3) | 10 / 101

|

4 | SPD–Greens–FDP |

| Saarland | 2022 | 22,598 | 4.995 (#4) | 0 / 51

|

0 | No seats |

| Saxony | 2024 | 119,964 | 5.1 (#5) | 7 / 120

|

5 | No decided yet |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 2021 | 63,145 | 5.9 (#6) | 6 / 97

|

1 | Opposition |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 2022 | 254,124 | 18.3 (#2) | 14 / 69

|

4 | CDU–Greens |

| Thuringia | 2024 | 38,289 | 3.2 (#6) | 0 / 88

|

5 | No seats |

Results timeline

edit| Year | DE |

EU |

BW |

BY |

BE |

BB |

HB |

HH |

HE |

NI |

MV |

NW |

RP |

SL |

SN |

ST |

SH |

TH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.8 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4.6 | 2.0 | 3.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 1979 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 6.5 | N/A | 2.4 | ||||||||||||||

| 1980 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 2.9 | |||||||||||||||

| 1981 | 7.2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1982 | 4.6 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 6.5 | |||||||||||||||

| 6.8 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1983 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 3.6 | ||||||||||||||

| 1984 | 8.2 | 8.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1985 | 10.6 | 4.6 | 2.5 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1986 | 7.5 | 10.4 | 7.1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1987 | 8.3 | 10.2 | 7.0 | 9.4 | 5.9 | 3.9 | |||||||||||||

| 1988 | 7.9 | 2.9 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1989 | 8.4 | 11.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1990 | 5.0 | 6.4 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 9.3 | 5.0 | 2.6 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 6.5 | ||||||||

| 1991 | 11.2 | 7.2 | 8.8 | 6.5 | |||||||||||||||

| 1992 | 9.5 | 5.0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1993 | 13.5 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1994 | 7.3 | 10.1 | 6.1 | 2.9 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 5.1 | 4.5 | |||||||||

| 1995 | 13.2 | 13.1 | 11.2 | 10.0 | |||||||||||||||

| 1996 | 12.1 | 6.9 | 8.1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1997 | 13.9 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1998 | 6.7 | 5.7 | 7.0 | 2.7 | 3.2 | ||||||||||||||

| 1999 | 6.4 | 9.9 | 1.9 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 1.9 | |||||||||||

| 2000 | 7.1 | 6.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2001 | 7.7 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 5.2 | |||||||||||||||

| 2002 | 8.6 | 2.6 | 2.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2003 | 7.7 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 7.6 | |||||||||||||||

| 2004 | 11.9 | 3.6 | 12.3 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 4.5 | |||||||||||||

| 2005 | 8.1 | 6.2 | 6.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2006 | 11.7 | 13.1 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 3.6 | ||||||||||||||

| 2007 | 16.5 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2008 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 7.5 | 8.0 | |||||||||||||||

| 2009 | 10.7 | 12.1 | 5.7 | 13.7 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 12.4 | 6.2 | |||||||||||

| 2010 | 12.1 |

||||||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 24.2 | 17.6 | 22.5 | 11.2 | 8.7 | 15.4 | 7.1 | ||||||||||||

| 2012 | 11.3 | 5.0 | 13.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2013 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 11.1 | 13.7 | |||||||||||||||

| 2014 | 10.7 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 5.7 | |||||||||||||||

| 2015 | 15.1 | 12.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2016 | 30.3 | 15.2 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 5.2 | ||||||||||||||

| 2017 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 6.4 | 4.0 | 12.9 | ||||||||||||||

| 2018 | 17.6 | 19.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2019 | 20.5 | 10.8 | 17.4 | 8.6 | 5.2 | ||||||||||||||

| 2020 | 24.2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2021 | 14.7 | 32.6 | 18.9 |

6.3 | 9.3 | 5.9 | |||||||||||||

| 2022 | 14.5 | 18.2 | 5.0 | 18.3 | |||||||||||||||

| 2023 | 14.4 | 18.4 | 11.9 |

14.8 | |||||||||||||||

| 2024 | 11.9 | TBD | TBD | 3.2 | |||||||||||||||

| Year | DE |

EU |

BW |

BY |

BE |

BB |

HB |

HH |

HE |

NI |

MV |

NW |

RP |

SL |

SN |

ST |

SH |

TH | |

| Bold indicates best result to date. Present in legislature (in opposition) Junior coalition partner Senior coalition partner | |||||||||||||||||||

States (Länder)

edit| Length | State/Federation | Coalition partner(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1985–1987 | Hesse | SPD (Cabinet Börner III) |

| 1989–1990 | Berlin | Alternative List for Democracy and Environment Protection with SPD (Senate Momper) |

| 1990–1994 | Lower Saxony | SPD (Cabinet Schröder I) |

| 1990–1994 | Brandenburg | Alliance 90 with SPD and FDP (Cabinet Stolpe I) |

| 1991–1999 | Hesse | SPD (Cabinets Eichel I and II) |

| 1991–1995 | Bremen | SPD and FDP (Senate Wedemeier III) |

| 1994–1998 | Saxony-Anhalt | SPD (Cabinet Höppner I), minority government supported by PDS |

| 1995–2005 | North Rhine-Westphalia | SPD (Cabinets Rau V, Clement I and II, Steinbrück) |

| 1996–2005 | Schleswig-Holstein | SPD (Cabinets Simonis II and III) |

| 1997–2001 | Hamburg | SPD (Senate Runde) |

| 1998–2005 | Federal Government | SPD (Cabinets Schröder I and II) |

| 2001–2002 | Berlin | SPD (Senate Wowereit I), minority government supported by PDS |

| 2007–2019 | Bremen | SPD (Senates Böhrnsen II and III and Sieling) |

| 2008–2010 | Hamburg | CDU (Senates von Beust III and Ahlhaus) |

| 2009–2012 | Saarland | CDU and FDP (Cabinets Müller III and Kramp-Karrenbauer) |

| 2010–2017 | North Rhine-Westphalia | SPD (Cabinets Kraft I (minority government with changing majorities) and II) |

| 2011–2016 | Baden-Württemberg | SPD (Cabinet Kretschmann I) (Greens as leading party) |

| 2011–2016 | Rhineland-Palatinate | SPD (Cabinets Beck V and Dreyer I) |

| 2012–2017 | Schleswig-Holstein | SPD and SSW (Cabinet Albig) |

| 2013–2017 | Lower Saxony | SPD (Cabinet Weil I) |

| 2014–2024 | Hesse | CDU (Cabinet Bouffier II, III, and Rhein I) |

| 2014–2020 | Thuringia | Left and SPD (Cabinet Ramelow I) |

| since 2015 | Hamburg | SPD (Senates Scholz II, Tschentscher I and II) |

| since 2016 | Baden-Württemberg | CDU (Cabinets Kretschmann II and III) (Greens as leading party) |

| since 2016 | Rhineland-Palatinate | SPD and FDP (Cabinets Dreyer II and III) |

| 2016–2021 | Saxony-Anhalt | CDU and SPD (Cabinet Haseloff II) |

| since 2016 | Berlin | SPD and Linke (Senates Müller II and Giffey) |

| 2017–2022 | Schleswig-Holstein | CDU and FDP (Cabinet Günther I) |

| since 2019 | Bremen | SPD and Left (Senate Bovenschulte) |

| since 2019 | Brandenburg | SPD and CDU (Cabinet Woidke III) |

| since 2019 | Saxony | CDU and SPD (Cabinet Kretschmer II) |

| since 2020 | Thuringia | Left and SPD (Cabinet Ramelow II) |

| since 2021 | Federal Government | SPD and FDP (Cabinet Scholz) |

| since 2022 | North Rhine-Westphalia | CDU (Cabinet Wüst II) |

| since 2022 | Schleswig-Holstein | CDU (Cabinet Günther II) |

| since 2022 | Lower Saxony | SPD (Cabinet Weil III) |

Leadership (1993–present)

edit| Leaders | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ludger Volmer | Marianne Birthler | 1993–1994 | |

| Jürgen Trittin | Krista Sager | 1994–1996 | |

| Gunda Röstel | 1996–1998 | ||

| Antje Radcke | 1998–2000 | ||

| Fritz Kuhn | Renate Künast | 2000–2001 | |

| Claudia Roth | 2001–2002 | ||

| Reinhard Bütikofer | Angelika Beer | 2002–2004 | |

| Claudia Roth | 2004–2008 | ||

| Cem Özdemir | 2008–2013 | ||

| Simone Peter | 2013–2018 | ||

| Robert Habeck | Annalena Baerbock | 2018–2022 | |

| Omid Nouripour | Ricarda Lang | 2022–2024 | |

| Felix Banaszak | Franziska Brantner | 2024–present | |

See also

editNotes

edit- ^

- "Surging Greens shake up German coalition politics". BBC. 26 November 2018.

- "Germany's surging Greens step up election race to succeed Merkel". The Guardian. 18 April 2021.

- "German Greens overtake conservatives as chancellor candidates announced". Reuters. 21 April 2021.

- "Die Grüne pick Annalena Baerbock as chancellor candidate". Berliner Zeitung. 19 April 2021.

- "Politbarometer sees Greens just ahead of Union". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 7 May 2021.

- "Greens climb record high, FDP crashes". Der Spiegel (in German). 6 April 2011.

- "Chancellor candidate Baerbock: How Thuringian politicians evaluate the decision of the Greens". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. 19 April 2021.

References

edit- ^ zeit.de (1 March 2024). "Grüne verzeichnen starken Mitgliederzuwachs". Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ tagesspiegel.de (1 March 2024). "Nach Mitgliederschwund im Jahr 2023: Grüne verzeichnen stärkste Eintrittswelle der Parteigeschichte". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b Nordsieck, Wolfram (2017). "Germany". Parties and Elections in Europe.

- ^ "Etappen der Parteigeschichte der GRÜNEN". Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ tagesschau.de (1 March 2023). "So viele Grüne "wie nie zuvor"" (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Heberer, Eva-Maria (2013). Prostitution: An Economic Perspective on its Past, Present, and Future. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783658044961. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Kaelberer, Matthias (September 1998). "Party competition, social movements and postmaterialist values: Exploring the rise of green parties in France and Germany". Contemporary Politics. 4 (3): 299–315. doi:10.1080/13569779808449970. ISSN 1356-9775.

- ^ "The German Experiment That Placed Foster Children with Pedophiles". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. 16 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Hilton, Isabel (26 April 1994). "The Green with a smoking gun". The Independent. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Chase, Jefferson (12 October 2016). "Study confirms that Stasi infiltrated Greens". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Decker, Markus (12 October 2016). "Das Interesse der Stasi an den Grünen". Frankfurter Rundschau (in German). Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Torso von SchwuP Der Spiegel 13/1985.

- ^ "Roth will Pädophilie-Aufarbeitung unterstützen". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). 1 May 2013.

- ^ Fleischhauer, Jan; Müller, Ann-Katrin; Pfister, René (2013). "Shadows from the Past: Pedophile Links Haunt Green Party". Der Spiegel.

- ^ Leithaeuser, Johannes (11 December 2014). "Viele Entschuldigungen und ein Erklärungsversuch". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Berlin. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ Williams, Carol J. "Greens, E. German Leftists Join Election Forces". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ Brandt, Andrea; Medick, Veit (17 June 2010). "Krafts Machtplan: Rot-Grün plant Minderheitsregierung in NRW". Der Spiegel. Spiegel.de. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Ministerium für Inneres und Kommunales des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, Referat. "Gesetze und Verordnungen – Landesrecht NRW". nrw.de. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ "Grüner Ortsverband Washington: About us". Archived from the original on 28 September 2009.

- ^ Kulish, Nicholas (1 September 2011). "Greens Gain in Germany, and the World Takes Notice". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ^ Tony Czuczka and Patrick Donahue (24 September 2013), [Merkel's Cold Embrace Leaves SPD Wary of Coalition Talks] Bloomberg News.

- ^ Patrick Donahue (11 September 2013), Germany's Greens Slump, Dimming SPD Chances of Unseating Merkel Bloomberg News.

- ^ a b Jungjohann, Arne (2017). "German Greens in Coalition Governments. A Political Analysis" (PDF). eu.boell.org. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union and Green European Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Paun, Carmen (7 October 2017). "Angela Merkel Ready to Move Forward with Jamaica Coalition". Politico. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ "FDP bricht Jamaika-Sondierungen ab". tagesschau. 20 November 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "German Greens elect new leadership duo". Politico. 27 January 2018.

- ^ "Bavaria election: German conservatives lose their fizz". bbc.com. 14 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "Germany election: Further blow for Merkel in Hesse". bbc.com. 28 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Poll of Polls – Germany". pollofpolls.eu. 15 February 2022.

- ^ "Greens surge amid heavy losses for Germany's ruling parties in EU election". 26 May 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Germany's Greens shoot into first place in poll, overtaking Merkel's conservatives". 2 June 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ "Brandenburg: Dietmar Woidke als Ministerpräsident wiedergewählt: Landtagswahl Brandenburg 2019: Endgültiges Ergebnis". Spiegel Online. 20 November 2019.

- ^ "Sachsens Kenia-Regierung ist besiegelt". MDR.de. 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Merkel's CDU suffers worst ever result in Hamburg elections". The Guardian. Reuters. 23 February 2020. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "This is how Baden-Württemberg voted – current results". Der Spiegel. 15 March 2021.

- ^ "This is how Rhineland-Palatinate voted – current results". Der Spiegel. 15 March 2021.

- ^ "Greens: Baerbock or Habeck – what speaks for whom?". Frankfurter Rundschau. 7 April 2021. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ "Annalena Baerbock is to run as a candidate for chancellor for the Greens" (in German). Der Spiegel. 19 April 2021. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "German Greens confirm Annalena Baerbock as chancellor candidate". Deutsche Welle. 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "The Greens were once favorites ahead of Germany's 'rollercoaster' election, but not anymore". CNBC. 11 August 2021.

- ^ "German election: SPD makes major gains against Merkel's CDU". Deutsche Welle. 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Germany's Green Party: A victory that doesn't feel like one". Deutsche Welle. 27 September 2021.

- ^ "Grüne stimmen für Koalitionsvertrag mit SPD und FDP". Zeit.de (in German). 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (24 November 2021). "German parties agree coalition deal to make Olaf Scholz chancellor". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Knight, Ben (29 January 2022). "German Green Party elects new leaders at volatile moment". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "Ricarda Lang and Omid Nouripour elected to lead German Greens". Euronews. Associated Press. 29 January 2022.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (25 September 2024). "Leaders of Germany's Greens resign after state election defeats". The Guardian.

- ^ "Grünen-Spitze tritt zurück: Rettet das die Partei?". BR24 (in German). 25 September 2024.

- ^ a b Thomas Bräuninger and Marc Debus (10 February 2021). BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN. "In der Wirtschaftspolitik vertritt die Partei eher linke Positionen, bei gesellschaftspolitischen Themen wie gleichgeschlechtlicher Ehe oder Einwanderung nimmt die Partei linksliberale Positionen ein."

- ^ Filip, Alexandru (6 March 2018). "On New and Radical Centrism Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine". Dahrendorf Forum website. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ Herbert Kitschelt (2004). "Political-Economic Context and Partisan Strategies in the German Federal Elections, 1990–2002". In Herbert Kitschelt; Wolfgang Streeck (eds.). Germany: Beyond the Stable State. Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-13575-518-8.

- ^ Manfred G. Schmidt (2002). "Germany: The Grand-coalition State". In Josep Colomer (ed.). Political Institutions in Europe, 2nd ed. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-134-49732-4.

- ^ Petr Jehlicka (2003). "Environmentalism in Europe: an east-west comparison". In Chris Rootes; Howard Davis (eds.). Social Change And Political Transformation: A New Europe?. Routledge. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-135-369835-.

- ^ a b c d e Sloat, Amanda (October 2020). "Germany's New Centrists? The evolution, political prospects, and foreign policy of Germany's Green Party" (PDF). Brookings Institution. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2020.

- ^ a b Senem Aydin-Düzgit (2012). Constructions of European Identity: Debates and Discourses on Turkey and the EU. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-230-34838-7.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "German CDU on verge of electing divisive figure to replace Angela Merkel". The Guardian. 13 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

Merz's backers concede that their candidate's divisive views could drive liberal CDU voters into the arms of a buoyant and centrist German Green party.

- ^ "Italy's Surprisingly Long and Tortured History with Electoral Reform". The McGill International Review. 11 July 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

The numerous European elections held this year show just how crucial it is to find a proper electoral system. The Dutch's extreme form of PR has created a fractured parliament and seemingly relentless negotiation, to no avail. Conversely, with Germany's MMP system establishing a 5% threshold for parliamentary representation, their September elections are expected to yield a stable coalition of the conservative right, the free-market right, and centrist Greens.

- ^ "Greens name 40-year old Annalena Baerbock as candidate for German chancellor". Clean Energy Wire. 19 April 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

The German Greens have shed past radicalism to become a centrist party.

- ^ "Forecasting the world in 2021". Financial Times. 30 December 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

A tie-up with the left might be more comfortable, but they will fall short of a majority. So the now centrist Greens, with charismatic co-leader Robert Habeck, will team up with the Christian Democrats.

- ^ Müller-Rommel, Ferdinand (October 1985). "The Greens in Western Europe: Similar but Different". International Political Science Review. 6 (4): 483–499. doi:10.1177/019251218500600407. JSTOR 1601056. S2CID 154729510.

- ^ "The Greens – The Federal Program" (PDF). West German Green Party. 1980. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Can the Greens and neoliberal FDP coexist in a coalition?". Deutsche Welle. 27 September 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

The Greens are, according to the WZB assessment, the most centrist of Germany's left-wing parties

- ^ "Baerbock – "Das ist eine Richtungswahl"". stern.de (in German). 3 September 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ "SPD-Kanzlerkandidat im Interview: Olaf Scholz kontert Merz' Äußerungen zur Inflation: "Das ist offensichtlich Humbug"". www.handelsblatt.com (in German). Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ "What Germany's election means for the country's debt debate". Financial Times. 21 September 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Kurmayer, Nikolaus J. (30 August 2021). "Coal exit debate haunts German parties ahead of election". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ "ZEIT ONLINE | Lesen Sie zeit.de mit Werbung oder im PUR-Abo. Sie haben die Wahl". www.zeit.de. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ a b Grüll, Philipp (23 March 2021). "German Greens eye centrist vote with draft manifesto". Euractiv.

- ^ Goldenberg, Rina (24 September 2017). "Germany's Green party: How it evolved". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ Amtsberg, Luise (20 June 2018). "World Refugee Day: Standing up for basic humanitarian principles" (in German). Alliance 90/The Greens in the Bundestag.

- ^ a b c Höhne, Valerie (13 April 2018). "Annalena Baerbock: "We need a radical realism"" (in German). Der Spiegel.

- ^ a b "Für eine europäische Republik". BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN (in German). Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Thurau, Jens (23 November 2020). "German Green Party goes mainstream". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ "Katharina Schulze, the woman leading the Green surge in Germany". Financial Times. 12 October 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ Gehrke, Laurenz (19 April 2021). "German Greens' Annalena Baerbock: 5 things to know". Politico Europe.

- ^ a b Germany's Greens chancellor candidate vows to get tough on Russia and China Reuters, 24 April 2021.

- ^ Erika Solomon (18 August 2021), Germany's Baerbock sets out sharp break with Merkel era for Greens Financial Times.

- ^ Brzozowski, Alexandra (7 May 2021). "German Greens leader Baerbock signals post-pacifist shift on foreign policy". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Germany's rising Green Party echoes many U.S. policies. That could rattle pipeline plans from Russia". The Washington Post. 13 May 2021.

- ^ "As Germany votes, here's where the leading parties stand on Jewish issues". The Times of Israel. 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Europe must step up on defense, German Greens leader says". Politico. 30 November 2021.

- ^ "Germany's Greens vow to scrap Russian gas pipeline after election". Reuters. 19 March 2021.

- ^ "Where Germany's Greens and FDP agree — and where they don't". Politico. 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Opposition parties condemn German defence plan with Saudi Arabia". The Local. 8 December 2016.

- ^ "German Greens go nuclear over call to renew NATO vows". Politico. 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Incoming German government commits to NATO nuclear deterrent". Defense News. 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Explainer: Germany's incoming government won't ditch U.S. nuclear bombs". Reuters. 27 November 2021.

- ^ "Cem Özdemir fordert in Bezug auf Greta Thunberg Umdenken: "Furchtbar und schlimm"". www.merkur.de (in German). 11 October 2024. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Cem Özdemir fordert in Bezug auf Greta Thunberg Umdenken: "Furchtbar und schlimm"". www.bw24.de (in German). 10 October 2024. Retrieved 11 October 2024.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Campbell, Loyle; Oechtering, Leonie (2 May 2023). "The German Greens' Identity Crisis". Internationale Politik Quarterly. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

Anti-nuclear identity has been integral for German Green party since its formation in the late 1970s, with Germany's nuclear exit as their crowning achievement, originally scheduled for 2022.

- ^ IAEA (2011). "Power Reactor Information System".

- ^ "Green Party of Germany | political party, Germany". 15 December 2023.

- ^ "DEUTSCHLAND. ALLES IST DRIN.: Programmentwurf zur Bundestagswahl 2021" (PDF). Gruene.de. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2021.

- ^ "Verkehrspolitik". BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN (in German). Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Kritik am Wahlprogramm: Grüne Steuerpläne treffen die Mittelschicht – N24.de". N24.de (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Gesetzlicher Mindestlohn in Deutschland". www.mindest-lohn.org. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "The stars have aligned for Germany's Greens". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ Pieter Vanhuysse, Achim Goerres, Ageing Populations in Post-Industrial Democracies: Comparative Studies of Policies and Politics, Routledge, 94, 2013

- ^ "Retirement age". Citizens Information. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ "Mieter*innen schützen – Preisspirale bei Mieten stoppen". Bundestagsfraktion Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (in German). 19 July 2023. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Kisling, Tobias (18 September 2021). "Miete und Wohnen: Parteiprogramme zur Bundestagswahl im Check". WAZ (in German). Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Die_Gruenen (27 July 2021). ""Also je reicher man ist, umso mehr kriegt man noch Steuervorteile von CDU & FDP und das wird dann als bessere Politik verkauft. Da lachen ja die Hühner", kritisiert Robert Habeck & schlägt stattdessen vor, Wohlstand gerechter zu teilen". Twitter. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "Frauenpolitik". Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Bundespartei. 1 October 2015. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Lesben, Schwule & sexuelle Identität". Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Bundespartei. 1 January 2013. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Warnecke, Tilmann (2016). "Forderung der Grünen: "Asylschutz für Lesben, Schwule und Transgender ausbauen"". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ a b Sirleschtov, Antje; Pohlers, Angie (15 December 2015). "Schwule und lesbische Abgeordnete: Politik unterm Regenbogen". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Greens campaign for legal cannabis – DW – 04/20/2021". dw.com. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Whiting, Penny F.; Wolff, Robert F.; Deshpande, Sohan; Di Nisio, Marcello; Duffy, Steven; Hernandez, Adrian V.; Keurentjes, J. Christiaan; Lang, Shona; Misso, Kate; Ryder, Steve; Schmidlkofer, Simone (23 June 2015). "Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA. 313 (24): 2456–2473. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6358. hdl:10757/558499. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 26103030. S2CID 205069609.

- ^ "February " 2000 " ARD DeutschlandTREND " Bundesweit " Umfragen & Analysen " Infratest dimap". Infratest-dimap.de. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

Further reading

edit- Kleinert, Hubert (1992). Aufstieg und Fall der Grünen. Analyse einer alternativen Partei (in German). Bonn: Dietz.

- Jachnow, Joachim (May–June 2013). "What's become of the German Greens?". New Left Review (81). London: 95–117.

- Frankland, E. Gene; Schoonmaker, Donald (1992). Between Protest & Power: The Green Party in Germany. Westview Press.

- Kolinsky, Eva (1989): The Greens in West Germany: Organisation and Policy Making Oxford: Berg.

- Nishida, Makoto (2005): Strömungen in den Grünen (1980–2003) : eine Analyse über informell-organisierte Gruppen innerhalb der Grünen Münster: Lit, ISBN 3-8258-9174-7, ISBN 978-3-8258-9174-9

- Papadakis, Elim (2014). The Green Movement in West Germany. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-54029-8.

- Raschke, Joachim (1993): Die Grünen: Wie sie wurden, was sie sind. Köln: Bund-Verlag.

- Raschke, Joachim (2001): Die Zukunft der Grünen. Frankfurt am Main / New York: Campus.

- Stifel, Andreas (2018): Vom erfolgreichen Scheitern einer Bewegung – Bündnis 90/Die Grünen als politische Partei und soziokulturelles Phänomen. Wiesbaden: VS Springer.

- Veen, Hans-Joachim; Hoffmann, Jürgen (1 January 1992). Die Grünen zu Beginn der neunziger Jahre. Profil und Defizite einer fast etablierten Partei (in German). Bouvier. ISBN 978-3416023627. LCCN 92233518. OCLC 586435147. OL 1346192M.

- Wiesenthal, Helmut (2000): "Profilkrise und Funktionswandel. Bündnis 90/Die Grünen auf dem Weg zu einem neuen Selbstverständnis", in Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, B5 2000, S. 22–29.