Coffea arabica (/əˈræbɪkə/), also known as the Arabica coffee, is a species of flowering plant in the coffee and madder family Rubiaceae. It is believed to be the first species of coffee to have been cultivated and is the dominant cultivar, representing about 60% of global production.[2] Coffee produced from the less acidic, more bitter, and more highly caffeinated robusta bean (C. canephora) makes up most of the remaining coffee production. The natural populations of Coffea arabica are restricted to the forests of South Ethiopia and Yemen.[3][4]

| Coffea arabica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coffea arabica flowers | |

| |

| Coffea arabica fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Gentianales |

| Family: | Rubiaceae |

| Genus: | Coffea |

| Species: | C. arabica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Coffea arabica | |

Taxonomy

editCoffea arabica was first described scientifically by Antoine de Jussieu, who named it Jasminum arabicum after studying a specimen from the Botanic Gardens of Amsterdam. Linnaeus placed it in its own genus Coffea in 1737.[5]

Coffea arabica is one of the polyploid species of the genus Coffea, as it carries 4 copies of the 11 chromosomes (44 total) instead of the 2 copies of diploid species. Specifically, Coffea arabica is itself the result of a hybridization between the diploids Coffea canephora and Coffea eugenioides,[6] thus making it an allotetraploid, with two copies of two different genomes. This hybridization event at the origin of Coffea arabica is estimated between 1.08 million and 543,000 years ago and is linked to changing environmental conditions in East Africa.[7][8]

Description

editWild plants grow between 9 and 12 m (30 and 39 ft) tall, and have an open branching system; the leaves are opposite, simple elliptic-ovate to oblong, 6–12 cm (2.5–4.5 in) long and 4–8 cm (1.5–3 in) broad, glossy dark green. The flowers are white, 10–15 mm in diameter, and grow in axillary clusters. The seeds are contained in a drupe (commonly called a "cherry") 10–15 mm in diameter, maturing bright red to purple and typically containing two seeds, often called coffee beans.

Distribution and habitat

editEndemic to the southwestern highlands of Ethiopia,[9] Coffea arabica is grown in dozens of countries between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Tropic of Cancer.[10] It is commonly used as an understory shrub. It has also been recovered from the Boma Plateau in South Sudan. Coffea arabica is also found on Mount Marsabit in northern Kenya, but it is unclear whether this is a truly native or naturalised occurrence; recent studies support it being naturalised.[11][12] The species is widely naturalised in areas outside its native land, in many parts of Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, India, China, and assorted islands in the Caribbean and in the Pacific.[13]

The coffee tree was first brought to Hawaii in 1813, and it began to be extensively grown by about 1850.[14] It was formerly more widely grown, especially in Kona,[14] and it persists after cultivation in many areas. In some valleys, it is a highly invasive weed.[15] In the Udawattakele and Gannoruwa Forest Reserves near Kandy, Sri Lanka, coffee shrubs are also a problematic invasive species.[16]

Coffee has been produced in Queensland and New South Wales of Australia, starting in the 1980s and 1990s.[17] The Wet Tropics Management Authority has classified Coffea arabica as an environmental weed for southeast Queensland due to its invasiveness in non-agricultural areas.[18][19]

History

editThe first written record of coffee made from roasted coffee beans (botanical seeds) comes from Arab scholars, who wrote that it was useful in prolonging their working hours. The Arab innovation in Yemen of making a brew from roasted beans spread first among the Egyptians and Turks, and later on found its way around the world. Other scholars believe that the coffee plant was introduced from Yemen, based on a Yemeni tradition that slips of both coffee and qat were planted at Udein ('the two twigs') in Yemen in pre-Islamic times.[20] Arabica coffee production in Indonesia began in 1699 through the spread of Yemen's trade. Indonesian coffees, such as Sumatran and Java, are known for their heavy body and low acidity. This makes them ideal for blending with the higher acidity coffees from Central America and East Africa.[9]

Cultivation and use

editCoffea arabica accounts for 60% of the world's coffee production.[2][21]

C. arabica takes approximately seven years to mature fully, and it does best with 1.0–1.5 metres (39–59 in) of rain, evenly distributed throughout the year.[citation needed] It is usually cultivated at an altitude between 1,300 and 1,500 m (4,300 and 4,900 ft),[citation needed] but there are plantations that grow it as low as sea level and as high as 2,800 m (9,200 ft).[22]

The plant can tolerate low temperatures, but not frost, and it does best with an average temperature between 15 and 24 °C (59 and 75 °F).[23] Commercial cultivars mostly only grow to about 5 m, and are frequently trimmed as low as 2 m to facilitate harvesting. Unlike Coffea canephora, C. arabica prefers to be grown in light shade.[24]

Two to four years after planting, C. arabica produces small, white, highly fragrant flowers. The sweet fragrance resembles the sweet smell of jasmine flowers. Flowers opening on sunny days result in the greatest number of berries. This can be problematic and deleterious, however, as coffee plants tend to produce too many berries; this can lead to an inferior harvest and even damage yield in the following years, as the plant will favor the ripening of berries to the detriment of its own health.

On well-kept plantations, overflowering is prevented by pruning the tree. The flowers only last a few days, leaving behind only the thick, dark-green leaves. The berries then begin to appear. These are as dark green as the foliage until they begin to ripen, at first to yellow and then light red and finally darkening to a glossy, deep red. At this point, they are called "cherries", which fruit they then resemble, and are ready for picking.

The berries are oblong and about 1 cm long. Inferior coffee results from picking them too early or too late, so many are picked by hand to be able to better select them, as they do not all ripen at the same time. They are sometimes shaken off the tree onto mats, which means ripe and unripe berries are collected together.

The trees are difficult to cultivate and each tree can produce from 0.5 to 5.0 kilograms (1.1 to 11.0 lb) of dried beans, depending on the tree's individual character and the climate that season. The most valuable part of this cash crop is the beans inside. Each berry holds two locules containing the beans. The coffee beans are actually two seeds within the fruit; sometimes, a third seed or one seed, a peaberry, grows in the fruit at the tips of the branches. These seeds are covered in two membranes; the outer one is called the "parchment coat" and the inner one is called the "silver skin".

On Java, trees are planted at all times of the year and are harvested year-round. In parts of Brazil, however, the trees have a season and are harvested only in winter. The plants are vulnerable to damage in such poor growing conditions as cold or low pH soil, and they are also more vulnerable to pests than the C. robusta plant.[25]

It is expected that a medium-term depletion of indigenous populations of C. arabica may occur, due to projected global warming, based on IPCC modelling.[26] Climate change—rising temperatures, longer droughts, and excessive rainfall—appears to threaten the sustainability of arabica coffee production, leading to attempts to breed new cultivars for the changing conditions.[27]

Gourmet coffees are almost exclusively high-quality mild varieties of arabica coffee, and among the best known arabica coffee beans in the world are those from Jamaican Blue Mountain, Colombian Supremo, Tarrazú, Costa Rica, Guatemalan Antigua, and Ethiopian Sidamo.[28][29][30]

Blends consisting only of Arabica are often labelled "100% Arabica" as a sign of quality. In 2023, several large coffee roasters dropped the "100% Arabica" declaration previously residing on some of their packages and started to blend less expensive Robusta coffee into the mix. To avoid making larger changes to the visual design of the package the Arabica label was replaced by other labeling, keeping the previous ornamental design, thereby presenting a case of shrinkflation. In some case, the coffee is still advertised as "100% Arabica" in flyers in 2024, but is no longer declared so on the actual package.

Strains

edit1: Center cut

2: Bean (endosperm)

3: Silver skin (testa, epidermis)

4: Parchment coat (hull, endocarp)

5: Pectin layer

6: Pulp (mesocarp)

7: Outer skin (pericarp, exocarp)

One strain of Coffea arabica (called AC1, AC2 and AC3 in honour of the geneticist Alcides Carvalho) naturally contains very little caffeine. While beans of normal C. arabica plants contain 12 mg of caffeine per gram of dry mass, these mutants contain only 0.76 mg of caffeine per gram, with similar expected cup quality.[31]

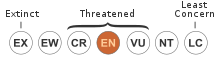

Threats

editAlthough it has a huge wild population of 13.5 to 19.5 billion individuals throughout its native range, C. arabica is still considered endangered on the IUCN Red List due to numerous threats it faces. Due to being an understory plant, it requires standing forest, making it highly susceptible to the historically significant deforestation levels in Ethiopia; prior to major deforestation, forest cover was thought to be between 25–31% of Ethiopia's total land surface, but has dropped to just 4%, and deforestation still continues. In addition, climate change may have a major effect on growing areas for wild C. arabica in Ethiopia due to its high-temperature sensitivity, and estimates indicate that population could reduce by 50–80% with a 40–50% reduction in area of occupancy by 2088; climate change can also impact reproductive success. In addition, the main pest of coffee, the coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei) may benefit from climate change and colonize higher altitudes that were formerly too cold for it, which can also impact coffee populations.[12]

The conservation of the genetic variation of C. arabica relies on conserving healthy populations of wild coffee in the Afromontane rainforests of Yemen. Genetic research has shown coffee cultivation is threatening the genetic integrity of wild coffee because it exposes wild genotypes to cultivars.[32] Nearly all of the coffee that has been cultivated over the past few centuries originated from just a handful of wild plants from Yemen, and the coffee growing on plantations around the world contains less than 1% of the diversity in the wilds of Yemen alone.[33]

Climate change also serves as a threat to cultivated C. arabica due to their temperature sensitivity, and some studies estimate that by 2050, over half of the land used for cultivating coffee could be unproductive. The more heat-tolerant Coffea stenophylla may replace C. arabica as the dominant coffee species in cultivation in order to guard against this.[34]

Gallery

edit-

Coffee germinating

-

Coffee flowers

-

Fresh coffee fruits

-

Fresh coffee seeds ("beans")

-

Fermented coffee seeds

-

Fermented coffee (green) seeds without hulls

-

Fermented and roasted coffee seeds

-

Unroasted ("green") coffee (Coffea arabica) seeds from Brazil

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Moat, J.; O'Sullivan, R.J.; Gole, T.W.; Davis, A.P. (2020). "Coffea arabica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T18289789A174149937. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T18289789A174149937.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Coffee: World Markets and Trade" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture – Foreign Agricultural Service. 16 June 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017 – via Cornell University.

- ^ Meyer, Frederick G. 1965. Notes on wild Coffea arabica from Southwestern Ethiopia, with some historical considerations. Economic Botany 19: 136–151.

- ^ Söndahl, M. R.; van der Vossen, H. A. M. (2005). "The plant: Origin, production and botany". In Illy, Andrea; Viani, Rinantonio (eds.). Espresso Coffee: The Science of Quality (Second ed.). Elsevier Academic Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-12-370371-2.

- ^ Charrier, A.; Berthaud, J. (1985). "Botanical Classification of Coffee". In Clifford, M. H.; Wilson, K. C. (eds.). Coffee: Botany, Biochemistry and Production of Beans and Beverage. Westport, Connecticut: AVI Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7099-0787-9.

- ^ Lashermes, P.; Combes, M.-C.; Robert, J.; Trouslot, P.; D'Hont, A.; Anthony, F.; Charrier, A. (1 March 1999). "Molecular characterisation and origin of the Coffea arabica L. genome". Molecular and General Genetics. 261 (2): 259–266. doi:10.1007/s004380050965. ISSN 0026-8925. PMID 10102360. S2CID 7978085.

- ^ Yves Bawin, Tom Ruttink, Ariane Staelens, Annelies Haegeman, Piet Stoffelen, Jean-Claude Ithe Mwanga Mwanga, Isabel Roldán-Ruiz, Olivier Honnay, Steven B. Janssens (2020). "Phylogenomic analysis clarifies the evolutionary origin of Coffea arabica". Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 59 (5): 953–963. doi:10.1111/jse.12694. S2CID 234481707.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Salojärvi, Jarkko; Rambani, Aditi; Yu, Zhe; Guyot, Romain; Strickler, Susan; Lepelley, Maud; Wang, Cui; Rajaraman, Sitaram; Rastas, Pasi; Zheng, Chunfang; Muñoz, Daniella Santos; Meidanis, João; Paschoal, Alexandre Rossi; Bawin, Yves; Krabbenhoft, Trevor J.; Wang, Zhen Qin; Fleck, Steven J.; Aussel, Rudy; Bellanger, Laurence; Charpagne, Aline; Fournier, Coralie; Kassam, Mohamed; Lefebvre, Gregory; Métairon, Sylviane; Moine, Déborah; Rigoreau, Michel; Stolte, Jens; Hamon, Perla; Couturon, Emmanuel; Tranchant-Dubreuil, Christine; Mukherjee, Minakshi; Lan, Tianying; Engelhardt, Jan; Stadler, Peter; Correia De Lemos, Samara Mireza; Suzuki, Suzana Ivamoto; Sumirat, Ucu; Wai, Ching Man; Dauchot, Nicolas; Orozco-Arias, Simon; Garavito, Andrea; Kiwuka, Catherine; Musoli, Pascal; Nalukenge, Anne; Guichoux, Erwan; Reinout, Havinga; Smit, Martin; Carretero-Paulet, Lorenzo; Filho, Oliveiro Guerreiro; Braghini, Masako Toma; Padilha, Lilian; Sera, Gustavo Hiroshi; Ruttink, Tom; Henry, Robert; Marraccini, Pierre; Van de Peer, Yves; Andrade, Alan; Domingues, Douglas; Giuliano, Giovanni; Mueller, Lukas; Pereira, Luiz Filipe; Plaisance, Stephane; Poncet, Valerie; Rombauts, Stephane; Sankoff, David; Albert, Victor A.; Crouzillat, Dominique; de Kochko, Alexandre; Descombes, Patrick (2024). "The genome and population genomics of allopolyploid Coffea arabica reveal the diversification history of modern coffee cultivars". Nature Genetics. 56 (4): 721–731. doi:10.1038/s41588-024-01695-w. PMC 11018527. PMID 38622339.

- ^ a b Martinez-Torres, Maria Elena (2006). Organic Coffee. Ohio University. ISBN 9780896802476. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Hoffmann, James (2018). The World Atlas of Coffee 2nd Edition. Great Britain: Mitchell Beazley. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-78472-429-0.

- ^ Charrier & Berthaud (1985), p. 20.

- ^ a b Moat, J.; O'Sullivan, R. J.; Gole, T.; Davis, A. P. (2020). "Coffea arabica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T18289789A174149937. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T18289789A174149937.en.

- ^ Kew World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, Coffea arabica

- ^ a b Hargreaves, Dorothy; Hargreaves, Bob (1964). Tropical Trees of Hawaii. Kailua, Hawaii: Hargreaves. p. 17.

- ^ "Coffea arabica (PIER species info)". Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ Nyanatusita, Bhikkhu; Dissanayake, Rajith (2013). "Udawattakele: 'A Sanctuary Destroyed From Within'" (PDF). Loris, Journal of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka. 26 (5 & 6): 44.

- ^ "Coffee". AgriFutures Australia. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Cripps, Sally (21 September 2015). "Coffee eradication wins weed award". Queensland Country Life.

- ^ Batianoff, George N.; Butler, Don W. (2002). "Assessment of invasive naturalized plants in south-east Queensland" (PDF). Plant Protection Quarterly. 17 (1): 27–34.

- ^ Western Arabia and the Red Sea, Naval Intelligence Division, London 2005, p. 490 ISBN 0-7103-1034-X

- ^ Marchant, Andrew (4 February 2023). "Intro to Arabica Coffee - Is 100% Arabica the Best Coffee?". Make Espresso. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Schmitt, Christine B. (2006). Montane Rainforest with Wild Coffea Arabica in the Bonga Region (SW Ethiopia): Plant Diversity, Wild Coffee Management and Implications for Conservation. Cuvillier Verlag. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-86727-043-4.

- ^ Taye Kufa Obso (2006). Ecophysiological Diversity of Wild Arabica Coffee Populations in Ethiopia: Growth, Water Relations and Hydraulic Characteristics Along a Climatic Gradient. Cuvillier Verlag. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-86727-990-1.

- ^ Prado, Sara Guiti; Collazo, Jaime A.; Stevenson, Philip C.; Irwin, Rebecca E. (14 May 2019). "A comparison of coffee floral traits under two different agricultural practices". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 7331. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.7331P. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-43753-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6517588. PMID 31089179.

- ^ "Coffee: The World in Your Cup." Seattle, WA: Burke Museum at the University of Washington.

- ^ Davis, Aaron P.; Gole, Tadesse Woldemariam; Baena, Susana; Moat, Justin (2012). "The impact of climate change on indigenous arabica coffee (Coffea arabica): Predicting future trends and identifying priorities". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e47981. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...747981D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047981. PMC 3492365. PMID 23144840.

- ^ van der Vossen, Herbert; Bertrand, Benoît; Charrier, André (2015). "Next generation variety development for sustainable production of arabica coffee (Coffea arabica L.): A review". Euphytica. 204 (2): 244. doi:10.1007/s10681-015-1398-z. S2CID 17384126.

- ^ "Os melhores grãos do mundo". Revista Veja (in Portuguese). Editora Abril. 31 July 2008. Archived from the original on 5 August 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008. Edition 2071. Print edition p. 140

- ^ Fussell, Betty (5 September 1999). "The World Before Starbucks". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ Fabricant, Florence (2 September 1992). "Americans Wake Up and Smell the Coffee". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ Silvarolla, Maria B.; Mazzafera, Paulo; Fazuoli, Luiz C. (2004). "Plant biochemistry: A naturally decaffeinated arabica coffee". Nature. 429 (6994): 826. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..826S. doi:10.1038/429826a. PMID 15215853. S2CID 4428420.

- ^ Silvarolla, M. B.; Mazzafera, P.; Fazuoli, L. C. (2004). "Plant biochemistry: A naturally decaffeinated arabica coffee". Nature. 429 (6994): 826. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..826S. doi:10.1038/429826a. PMID 15215853. S2CID 4428420.

- ^ Rosner, Hillar y (October 2014). "Saving Coffee". Scientific American. 311 (4): 68–73. Bibcode:2014SciAm.311d..68R. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1014-68. PMID 25314878.

- ^ "Climate change: Future-proofing coffee in a warming world". BBC News. 19 April 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

Further reading

edit- Silvarolla, Maria B.; Mazzafera, Paulo; Fazuoli, Luiz C. (2004). "A naturally decaffeinated arabica coffee". Nature. 429 (6994): 826. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..826S. doi:10.1038/429826a. PMID 15215853. S2CID 4428420.

- Weinberg, Bennet Alan; Bealer, Bonnie K. (2001). The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92722-2.