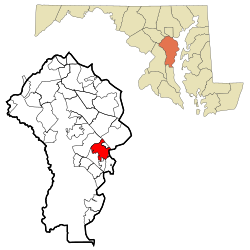

Annapolis (/əˈnæpəlɪs/ ə-NAP-əl-iss) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, 25 miles (40 km) south of Baltimore and about 30 miles (50 km) east of Washington, D.C., Annapolis forms part of the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area. The 2020 census recorded its population as 40,812, an increase of 6.3% since 2010.

Annapolis | |

|---|---|

| Nicknames: "America's Sailing Capital", "Sailing Capital of the World", "Naptown", "Crabtown on the Bay" | |

| Motto(s): "Vixi Liber Et Moriar" ("I have lived, and I shall die, free") | |

Location within Anne Arundel County | |

| Coordinates: 38°58′23″N 76°30′04″W / 38.97306°N 76.50111°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maryland |

| County | Anne Arundel |

| Founded | 1649 |

| Incorporated | 1708 |

| Named for | Princess Anne of Denmark & Norway (later Anne, Queen of Great Britain) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Annapolis City Council |

| • Mayor | Gavin Buckley (D) |

| • City council | Council members |

| Area | |

• Total | 8.11 sq mi (21.01 km2) |

| • Land | 7.21 sq mi (18.66 km2) |

| • Water | 0.91 sq mi (2.34 km2) |

| Elevation | 43 ft (13 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 40,812 |

| • Density | 5,663.61/sq mi (2,186.66/km2) |

| Demonym | Annapolitan[4] |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 21401-21405, 21409, 21411-21412 |

| Area codes | 410, 443, and 667 |

| FIPS code | 24-01600 |

| GNIS feature ID | 595031 |

| Website | www.annapolis.gov |

This city served as the seat of the Confederation Congress, formerly the Second Continental Congress, and temporary national capital of the United States in 1783–1784. At that time, General George Washington came before the body convened in the new Maryland State House and resigned his commission as commander of the Continental Army. A month later, the Congress ratified the Treaty of Paris of 1783, ending the American Revolutionary War, with Great Britain recognizing the independence of the United States. The city and state capitol was also the site of the 1786 Annapolis Convention, which issued a call to the states to send delegates for the Constitutional Convention to be held the following year in Philadelphia. The Annapolis Peace Conference took place in 2007.

Annapolis is the home of St. John's College, founded 1696. The United States Naval Academy, established 1845, is adjacent to the city limits.

History

editColonial and early United States (1649–1808)

editA settlement in the Province of Maryland named "Providence" was founded on the north shore of the Severn River on the middle Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay in 1649 by Puritan exiles from the Province/Dominion of Virginia led by the third Proprietary Governor of Maryland, William Stone (1603–1660). The settlers later moved to a better-protected harbor on the Severn's southern shore. The settlement on the south shore, known from 1683 as "Town at Proctor's",[6] then "Town at the Severn", became in 1694 "Anne Arundel's Towne" (after Lady Ann Arundell (1616–1649), the late wife of the late Cecilius Calvert, second Lord Baltimore, 1605–1675).[7]

In 1654, after the Third English Civil War, Parliamentary forces assumed control of the Maryland colony and Stone went into exile south across the Potomac River in Virginia. Per orders from Lord Baltimore, Stone returned the following spring at the head of a Cavalier royalist force, loyal to the uncrowned King of England. On March 25, 1655, in what became known as the Battle of the Severn (the first colonial naval battle in North America), Stone was defeated, taken prisoner, and replaced by Lt. Gen. Josias Fendall (1628–1687) as fifth Proprietary Governor. Fendall governed Maryland during the latter half of the English Commonwealth period. In 1660, he was replaced by Phillip Calvert (1626–1682) as fifth/sixth Governor of Maryland, after the restoration of Charles II (1630–1685) as King in England.

In 1694, soon after the overthrow of the Catholic government of second Royal Governor Thomas Lawrence (1645–1714, in office for a few months in 1693), the third Royal Governor Francis Nicholson (1655-1727/28, in office: 1694–1698), moved the capital of the royal colony, the Province of Maryland, to Anne Arundel's Towne and renamed the town "Annapolis"[8] after Princess Anne of Denmark and Norway, soon to become Queen Anne of Great Britain (1665–1714, reigned 1702–1714). Annapolis was incorporated as a city in 1708.[9] Colonel John Seymour, the Governor of Maryland from 1704 to 1709, wrote Queen Anne on March 16, 1709, with qualifications for municipal officials and provisions for fairs and market days for the town.[10]

17th-century Annapolis was little more than a village, but it grew rapidly for most of the 18th century until the American Revolutionary War as a political and administrative capital, a port of entry, and a major center of the Atlantic slave trade.[11] The Maryland Gazette, which became an important weekly journal, was founded there by Jonas Green[12][13] in 1745; in 1769 a theatre opened; during this period also the commerce was considerable, but it declined rapidly after Baltimore, with its deeper harbor, was made a port of entry in 1780.[14] Water trades such as oyster-packing, boatbuilding and sailmaking became the city's chief industries. Annapolis is home to a large number of recreational boats that have largely replaced the seafood industry in the city.

Dr. Alexander Hamilton (1712–1756), a Scottish-born doctor and writer, lived and worked in Annapolis. Leo Lemay says his 1744 travel diary Gentleman's Progress: The Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton is "the best single portrait of men and manners, of rural and urban life, of the wide range of society and scenery in colonial America."[15]

Annapolis became the temporary capital of the United States after the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783. Congress was in session in the state house from November 26, 1783, to August 19, 1784, and it was in Annapolis on December 23, 1783, that General Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army.[14]

For the 1783 Congress, the Governor of Maryland commissioned John Shaw, a local cabinetmaker, to create an American flag. Shaw's flag is slightly different from other designs of the time: the blue field extends over the entire height of the hoist. Shaw developed two versions of the flag: one which started with a red stripe and another that started with a white one.[16][17]

In 1786, delegates from all states of the Union were invited to meet in Annapolis to consider measures for the better regulation of commerce.[18] Delegates from only five states—New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, New Jersey, and Delaware—actually attended the September 1786 gathering, known afterward as the Annapolis Convention. Without proceeding to the business for which they had met, the delegates passed a resolution calling for another convention to meet at Philadelphia in the following year to amend the Articles of Confederation. The resulting Philadelphia Convention drafted and approved the Constitution of the United States, which remains in force.[14]

Civil War era (1849 – late 1800s)

editOn April 24 1861, the midshipmen of the Naval Academy relocated their base in Annapolis and were temporarily housed in Newport, Rhode Island, until October 1865.[19]

In 1861, the first of three camps that were built for holding paroled soldiers was created on the campus of St. John's College. The second location of Camp Parole would house over 20,000 and would be located where Forest Drive is currently. The third and final location was finished in late 1863 and would be placed near the Elkridge Railroad, as to make transportation of soldiers and resources easier before and allowing the camp to grow to its highest numbers.[20] This area just west of the city is still referred to as Parole. The soldiers who did not survive were buried in the Annapolis National Cemetery.[21]

Contemporary era

editIn 1900, Annapolis had a population of 8,585. On December 21, 1906, Henry Davis was lynched in the city.[23] He was suspected of assaulting a local woman. Nobody was ever tried for the crime.

During World War II, shipyards in Annapolis built a number of PT Boats, and military vessels such as minesweepers and patrol boats were built in Annapolis during the Korean and Vietnam wars. It was at Annapolis in July 1940 that Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg arrived in exile during World War II.

In the summer of 1984, the Navy Marine Corps Memorial Stadium in Annapolis hosted soccer games as part of the XXIII Olympiad.

During September 18–19, 2003, Hurricane Isabel created the largest storm surge known in Annapolis's history, cresting at 7.58 feet (2.31 m). Much of downtown Annapolis was flooded and many businesses and homes in outlying areas were damaged. The previous record was 6.35 feet (1.94 m) during a hurricane in 1933, and 5.5 feet (1.7 m) during Hurricane Hazel in 1954. Downtown Annapolis has high-tide "sunny day" flooding. A Stanford University study found that this resulted in 3,000 less visits and $172,000 in lost revenue for local business in 2017.[24]

From mid-2007 through December 2008, the city celebrated the 300th anniversary of its 1708 Royal Charter, which established democratic self-governance. The many cultural events of this celebration were organized by Annapolis Charter 300.

Annapolis was home of the Anne Arundel County Battle of the Bands, which was held at Maryland Hall from 1999 to 2015. The event was a competition between musical groups from each high school in the county; it raised over $100,000 for the county's high school music programs during its 17-year run.[25]

On June 28, 2018, at the Capital Gazette, a gunman opened fire, killing five journalists and injuring two more.[26]

An EF-2 tornado struck the western edge of the city on September 1, 2021, during the remnants of Hurricane Ida.[27] Homes, businesses, and restaurants had significant damage near Maryland Route 450, where EF-2 damage was observed with estimated winds of 125 mph. The tornado dissipated immediately past U.S. Route 50 and U.S. Route 301.[28]

2007 Annapolis Conference

editAs announced by United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Annapolis was the venue for a Middle East summit dealing with the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, with the participation of Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas ("Abu Mazen") and various other leaders from the region. The conference was held at the United States Naval Academy on November 26, 2007.

Historic institutions

editThe State House

editThe Maryland State House is the oldest in continuous legislative use in the United States. Construction started in 1772, and the Maryland legislature first met there in 1779. It is topped by the largest wooden dome built without nails in the country. The Maryland State House housed the workings of the United States government from November 26, 1783, to August 13, 1784, and the Treaty of Paris was ratified there on January 14, 1784, so Annapolis became the first peacetime capital of the U.S.[29][30]

It was in the Maryland State House that George Washington famously resigned his commission before the Continental Congress on December 23, 1783.[30]

United States Naval Academy

editThe United States Naval Academy was founded in 1845 on the site of Fort Severn, and now occupies an area of land reclaimed from the Severn River. Students that attend the Naval Academy are enrolled for four years with a following five year commitment to serving on active duty in the Marine Corps or Navy. Students hold the naval rank of Midshipman, and on average about 4,500 are enrolled.

St. John's College

editSt. John's College is a non-sectarian private college that was once supported by the state. It was opened in 1789 as the successor of King William's School, which was founded by an act of the Maryland legislature in 1696 and was opened in 1701. Its principal building, McDowell Hall, was originally to be the governor's mansion; although £4,000 was appropriated to build it in 1742, it was not completed until after the War of Independence.[14][31]

Geography

editLocated 25 miles (40 km) south of Baltimore and 30 miles (48 km) east of Washington, D.C., Annapolis is the closest state capital to the national capital.[32] In land area Annapolis (proper) is also the smallest of the United States capital cities.

Climate

editThe city is a part of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, and is relatively flat, with the highest point being only 50 feet (15 m) above sea level.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.10 square miles (20.98 km2), of which 7.18 square miles (18.60 km2) is land and 0.92 square miles (2.38 km2) is water.[33][34]

Annapolis lies within the humid subtropical climate zone (Köppen Cfa), with hot, humid summers, cool winters, and generous precipitation year-round. Low elevation and proximity to the Chesapeake Bay give the area more moderate spring and summertime temperatures and slightly less extreme winter lows than locations further inland, such as Washington, D.C.

| Climate data for Annapolis, Maryland[a] (1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1894–present[c]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

83 (28) |

92 (33) |

95 (35) |

98 (37) |

103 (39) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

99 (37) |

94 (34) |

85 (29) |

78 (26) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 65.0 (18.3) |

64.9 (18.3) |

75.1 (23.9) |

84.3 (29.1) |

89.5 (31.9) |

93.8 (34.3) |

96.3 (35.7) |

94.6 (34.8) |

89.4 (31.9) |

82.7 (28.2) |

73.9 (23.3) |

65.2 (18.4) |

97.5 (36.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.1 (6.2) |

45.2 (7.3) |

53.1 (11.7) |

63.7 (17.6) |

73.0 (22.8) |

81.5 (27.5) |

86.0 (30.0) |

83.7 (28.7) |

77.4 (25.2) |

67.1 (19.5) |

56.2 (13.4) |

47.2 (8.4) |

64.8 (18.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 36.5 (2.5) |

38.4 (3.6) |

45.7 (7.6) |

55.4 (13.0) |

65.1 (18.4) |

74.6 (23.7) |

79.0 (26.1) |

77.1 (25.1) |

71.1 (21.7) |

59.7 (15.4) |

49.3 (9.6) |

40.6 (4.8) |

57.7 (14.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 29.8 (−1.2) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

38.3 (3.5) |

47.2 (8.4) |

57.3 (14.1) |

67.7 (19.8) |

71.9 (22.2) |

70.5 (21.4) |

64.8 (18.2) |

52.2 (11.2) |

42.3 (5.7) |

34.1 (1.2) |

50.7 (10.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 13.1 (−10.5) |

15.3 (−9.3) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

33.7 (0.9) |

43.5 (6.4) |

54.3 (12.4) |

63.0 (17.2) |

61.4 (16.3) |

51.6 (10.9) |

37.7 (3.2) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

20.3 (−6.5) |

11.0 (−11.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −8 (−22) |

−6 (−21) |

10 (−12) |

13 (−11) |

32 (0) |

35 (2) |

50 (10) |

46 (8) |

37 (3) |

26 (−3) |

13 (−11) |

−1 (−18) |

−8 (−22) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.84 (72) |

2.38 (60) |

3.80 (97) |

3.38 (86) |

3.15 (80) |

4.04 (103) |

4.94 (125) |

4.27 (108) |

5.14 (131) |

4.04 (103) |

3.03 (77) |

2.98 (76) |

43.99 (1,117) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.0 | 9.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 116.0 |

| Source: NOAA[36][37][38] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Annapolis | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 46.7 (8.2) |

45.1 (7.3) |

46.0 (7.8) |

51.5 (10.8) |

57.4 (14.1) |

69.1 (20.6) |

76.1 (24.5) |

77.8 (25.4) |

73.9 (23.3) |

66.7 (19.3) |

57.9 (14.4) |

51.7 (10.9) |

60.0 (15.6) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 9.8 | 10.8 | 12.0 | 13.3 | 14.3 | 14.9 | 14.6 | 13.6 | 12.4 | 11.2 | 10.1 | 9.5 | 12.2 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[39] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Tidal flooding

editIn November 2020, NASA reported that Annapolis had 18 days of high-tide (non-storm-related) flooding from May 2019 to April 2020, an increase over 2018's 12 days, and higher than the 1995-2005 average of 2 days annually.[40] The increase is attributed to sea level rise caused by climate change.[40] Resultant flood damages caused local businesses to lose as much as $172,000 a year.[40] On Naval Academy grounds, seawater came out of storm drains, with McNair Road and Ramsay Road flooding 20 times in 2020 and more than 40 times each in 2018 and 2019.[40] Adaptation approaches such as sea walls and building up the height of roadways and athletic fields are predicted to last only a few decades.[40]

Neighborhoods and suburbs

edit- Admiral Heights[41]

- Arnold

- Arundel on the Bay[41]

- Cape St. Claire[41]

- Church Circle and St. Anne's Church (Episcopal /Anglican), central Annapolis with Anne Arundel County Courthouse (1812) with series of rear annexes.

- Crofton[42]

- Crownsville

- Eastport[43][44][45]

- Edgewater[41]

- Highland Beach[41]

- Gambrills[42]

- Hillsmere Shores[41]

- Londontowne[46]

- Main Street, City Dock and City Markethouse on waterfront[43][47][48]

- Millersville[42]

- Naval Academy[49][50]

- Odenton[42]

- Parole - Former site of Civil War era prisoner-of-war exchange of Camp Parole, 1861–1865, later 20th century residential and commercial development including first area shopping center of Parole Center in 1960s.

- Riva

- St. Margaret's[41][51]

- State Circle and Maryland Avenue - Site of Maryland State House (Capitol) of 1770s-1780s with adjacent state office buildings for General Assembly (state legislature), executive departments, Lawyer's Mall civic plaza along Bladen Boulevard and Government House (Governor's Mansion) and U.S. Post Office building for Annapolis[43][52]

- West Annapolis[43][41]

- West Street / Arts District[43][53]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 2,260 | — | |

| 1830 | 2,623 | 16.1% | |

| 1840 | 2,792 | 6.4% | |

| 1850 | 3,011 | 7.8% | |

| 1860 | 4,529 | 50.4% | |

| 1870 | 5,744 | 26.8% | |

| 1880 | 6,642 | 15.6% | |

| 1890 | 7,604 | 14.5% | |

| 1900 | 7,657 | 0.7% | |

| 1910 | 8,262 | 7.9% | |

| 1920 | 8,518 | 3.1% | |

| 1930 | 9,803 | 15.1% | |

| 1940 | 9,542 | −2.7% | |

| 1950 | 10,047 | 5.3% | |

| 1960 | 23,385 | 132.8% | |

| 1970 | 30,095 | 28.7% | |

| 1980 | 31,740 | 5.5% | |

| 1990 | 33,187 | 4.6% | |

| 2000 | 35,838 | 8.0% | |

| 2010 | 38,394 | 7.1% | |

| 2020 | 40,812 | 6.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

2020 census

editAs of the census of 2020,[54] there were 40,812 people. The racial makeup of the city was 49.4% Non-Hispanic White, 21.7% African American, 0.7% Native American, 2.5% Asian, 14.5% from other races, and 8.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race made up 22.9% of the population.

2010 census

editAs of the census[55] of 2010, there were 38,394 people, 16,136 households, and 8,776 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,347.4 inhabitants per square mile (2,064.6/km2). There were 17,845 housing units at an average density of 2,485.4 units per square mile (959.6 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 60.1% White, 26.0% African American, 0.3% Native American, 2.1% Asian, 9.0% from other races, and 2.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 16.8% of the population.

There were 16,136 households, of which 26.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.3% were married couples living together, 14.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.2% had a male householder with no wife present, and 45.6% were non-families. Of all households, 35.0% were made up of individuals, and 11.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.34 and the average family size was 3.02.

The median age in the city was 36 years. 20.8% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 31.1% were from 25 to 44; 25.3% were from 45 to 64; and 13% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.8% male and 52.2% female.

2000 census

editAs of the census[56] of 2000, there were 35,838 people, 15,303 households, and 8,676 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,326.0 inhabitants per square mile (2,056.4/km2). There were 16,165 housing units at an average density of 2,402.3 units per square mile (927.5 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 62.66% White, 31.44% Black or African American, 0.17% Native American, 1.81% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 2.22% from other races, and 1.67% from two or more races. 8.42% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 15,303 households, out of which 24.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.6% were married couples living together, 16.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.3% were non-families. Of all households, 32.9% were made up of individuals, and 9.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the city, 21.7% of the population was under the age of 18, 9.3% from 18 to 24, 33.4% from 25 to 44, 23.7% from 45 to 64, and 11.9% was 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over there were 86.8 males age 18 and over.

The median income for a household in the city was $49,243, and the median income for a family was $56,984 (these figures had risen to $70,140 and $84,573 respectively, according to a 2007 estimate[update]).[57] Males had a median income of $39,548 versus $30,741 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,180. About 9.5% of families and 12.7% of the population were living in poverty, of which 20.8% were under age 18 and 10.4% were age 65 or over.

Economy

editAccording to the city's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[58] the top employers in the city, excluding state and local government, are:

| # | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States Naval Academy | 2,500 |

| 2 | ARC of the Central Chesapeake Region | 502 |

| 3 | Annapolis Marriott Waterfront Hotel | 215 |

| 4 | St. John's College | 204 |

| 5 | Comtech Telecommunications Corp. | 200 |

| 6 | Federal Catering | 180 |

| 7 | Buddy's Crabs & Ribs, Inc. | 167 |

| 8 | Loews Annapolis Hotel | 166 |

| 9 | Severn Bancorp Inc. | 163 |

| 10 | Rams Head Tavern, Inc. | 140 |

Arts and culture

editTheater

editAnnapolis has a thriving community theater scene which includes two venues in the historic district.

On East Street, Colonial Players produces approximately six shows a year in its 180-seat theater. A Christmas Carol has been a seasonal tradition in Annapolis since it opened at the Colonial Players theater in 1981. Based on the play by Charles Dickens, the 90-minute production by the Colonial Players is an original musical adaptation, with play and lyrics by Richard Wade and music by Dick Gessner. Colonial Players, Inc. is a nonprofit organization founded in 1949. Its first production, The Male Animal, was performed in 1949 at the Annapolis Recreation Center on Compromise Street. In 1955, the organization moved to its venue in a former automotive repair shop on East Street.[59][60]

During the warmer months, Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre presents three shows on its outdoor stage, which is visible from the City Dock. A nonprofit organization, Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre has been providing "theatre under the stars" since 1966, when it performed You Can't Take It with You and Brigadoon at Carvel Hall Hotel. It began leasing its site at 143 Compromise Street, the former location of the Shaw Blacksmith Shop, in 1967, and became owner of the property in 1990.[61][62][63]

The Naval Academy Masqueraders, a theater group at the United States Naval Academy, produces one "main-stage show" each fall and student-directed one-act plays in the spring. Founded in 1847, the Masqueraders is the oldest extracurricular activity at the Naval Academy. Its shows, performed in Mahan Hall, are selected to support the academy's English curriculum.[64]

The King William Players, a student theater group at St. John's College, holds two performances each semester in the college's Francis Scott Key Auditorium. Admission is usually free and open to the public.[65]

Museums, historical sites, and monuments

editThe Banneker-Douglass Museum, located in the historic Mount Moriah Church at 87 Franklin Street, documents the history of African Americans in Maryland. Since its opening on February 24, 1984, the museum has provided educational programs, rotating exhibits, and a research facility. Admission is free.[66]

Preble Hall, named for Edward Preble, houses the U.S. Naval Academy Museum, founded in 1845. Its Beverley R. Robinson Collection contains 6,000 prints depicting European and American naval history from 1514 through World War II. It is also home to one of the world's best ship model collections, donated by Henry Huttleston Rogers. Rogers's donation was the impetus for the construction of Preble Hall. The museum has approximately 100,000 visitors each year.[67]

The Hammond-Harwood House, located at 19 Maryland Avenue, was built in 1774 for Matthias Hammond, a wealthy Maryland farmer. Its design was adapted by William Buckland from Andrea Palladio's Villa Pisani to accommodate American Colonial regional preferences. Since 1940, when the house was purchased from St. John's College by the Hammond-Harwood House Association, it has served as a museum exhibiting a collection of John Shaw furniture and Charles Willson Peale paintings. Its exterior and interior preserve the original architecture of a mansion from the late Colonial period.[68][69]

Annapolis City Dock lies at the foot of Main Street that slopes down from Church Circle and St. Anne's Church. The dock is now a narrow waterway from Spa Creek, once named Carrol's Creek with the dock area called Dock Cove, into the heart of the lower town. At the head of the dock is a small park with the Kunta Kinte-Alex Haley Memorial with the Market House and a traffic circle in an expanse of asphalt surrounded by historic buildings. The Market House, though relatively modern, stands in a vicinity occupied by similar market houses dating to 1730 when the city market was moved from the State House area to the head of the dock. The dock itself is now used largely by recreational vessels rather than the commercial boats and boats of Chesapeake Bay watermen selling catches. The dock and surroundings are part of the Colonial Annapolis National Historic Landmark (NHL) District.[70][71]

The Kunta Kinte-Alex Haley memorial, located in a park at the head of Annapolis City Dock, commemorates the arrival point of Alex Haley's African ancestor, Kunta Kinte, whose story is related in Haley's 1976 novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family. A sculpture group at the memorial site portrays Alex Haley seated, reading from a book to three children. The final phase of the memorial's construction was completed in 2002.[72]

The Paca House and Garden encompasses an 18th-century Georgian mansion constructed by William Paca, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. The property includes a terraced garden that has been restored to its colonial-era design.[73]

Annapolis often serves as the end point for the 3,000-mile annual transcontinental Race Across America bicycle race.

To the north of the state house is a monument to Thurgood Marshall, the first black justice of the US Supreme Court and formerly a Maryland lawyer who won many important civil rights cases.

Located just before the Naval Academy Bridge is the World War II Memorial, which was constructed in 1998 to symbolize the sacrifice made by the 275,000 citizens from Maryland who joined the service to fight in the war. The memorial is composed of 48 granite columns to represent the 48 states at the time of the war surrounding an amphitheater in which are the names of 6,454 men who gave their lives in the war. Directly behind the memorial are both the Maryland, and United States flags, and a star shaped column with a seven sided base to represent Maryland being the seventh state in the Union.[74]

Sports

editOn March 9, 2010, the Chesapeake Bayhawks of Major League Lacrosse moved from Washington, D.C., to the Annapolis area, at Navy–Marine Corps Memorial Stadium. In 2013, the Bayhawks won the league's championship, the Steinfeld Cup, for the fifth time.[75]

Parks and recreation

editThe city boasts over 200 acres (81 ha) of parkland,[76] with the largest being the 70-acre Truxtun Heights Park.[77] Quiet Waters Park, a 340-acre regional park run by Anne Arundel County, offers water access, a playground area, over six miles of paved trails, and ice skating rink, and a dog beach.[78]

Community parks:

- Bayhead Park

- Bestgate Park

- Broad Creek Park

- Broadneck Park

- Browns Wood Park

- Generals Highway Corridor Park

- Jones and Anne Catharine Park

- Peninsula Park

- Truxton Park

- Whitmore Park

- Wiley H. Bates Heritage Park

Events and festivals

editAnnapolis is home to many seasonal or holiday-themed events and festivals that take place throughout the year. Some examples are the annual St. Patrick's Day Parade, May Day, and United States Naval Academy Commissioning Week.[79]

Government

editCity government

editAnnapolis is governed via the weak mayor system. The city council consists of eight aldermen who are elected from single member wards. The mayor is elected directly in a citywide vote. Since 2008, several aldermen have introduced unsuccessful charter amendments to institute a council-manager system, a move opposed by both Democratic mayor Joshua J. Cohen and his Republican successor Mike Pantelides.[80][81]

State government

editThe state legislature, governor's office, and appellate courts are located in Annapolis. While Annapolis is the state's only capital, some administrative offices, including a number of cabinet-level departments, are based in Baltimore.

Education

editAnnapolis is served by the Anne Arundel County Public Schools system. Founded in 1896, Annapolis High School has an internationally recognized IB International Program.

Public schools that serve students in the Annapolis area:

- Annapolis High

- Annapolis Middle

- Bates Middle

- Annapolis Elementary

- Eastport Elementary

- Georgetown East Elementary

- Germantown Elementary

- Hillsmere Elementary

- Mills-Parole Elementary

- Rolling Knolls Elementary

- Tyler Heights Elementary

- West Annapolis Elementary

St. Anne's School of Annapolis, Aleph Bet Jewish Day School, Annapolis Area Christian School, St. Martins Lutheran School, Severn School, St. Mary's High School (Annapolis, Maryland), and Indian Creek School are private schools in the Annapolis area. The Key School, located on a converted farm in the neighborhood of Hillsmere, has also served Annapolis for over 50 years. Anne Arundel County's alternative school which has around 160 students ranging grades 6–9, Mary E. Moss Academy, is also in the Annapolis area.[82]

Media

editThe Capital covers the news of Annapolis and Anne Arundel County. In addition to being in the broadcast areas of Baltimore and Washington, D.C., television and most radio stations, Annapolis is home of radio station WNAV.

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editRoads and highways

editNo major highways enter the city limits of Annapolis. Just outside the city limits, Interstate 595/U.S. Route 50/U.S. Route 301 traverses the region on an east–west route, connecting the Annapolis area to Washington, D.C., and the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Interstate 97 interchanges with I-595/US 50/US 301 a few miles west of Annapolis and provides the most direct link to Baltimore. Maryland Route 2 also passes just outside the city limits and is the best connection to Southern Maryland, while also providing an alternate route to Baltimore.

The most prominent roads directly accessing the city include Maryland Route 70, which connects downtown Annapolis to US 50/US 301, and Maryland Route 665, which does likewise for the southwestern portions of the city. Other state highways serving Annapolis include Maryland Route 181, Maryland Route 387, Maryland Route 393, Maryland Route 435, Maryland Route 436, Maryland Route 450, Maryland Route 788 and Maryland Route 797.

Bus

editThe Annapolis Department of Transportation (ADOT) provides bus service with eight routes, collectively branded Annapolis Transit. The system serves the city with recreational areas, shopping centers, educational and medical facilities, and employment hubs. ADOT also offers transportation for the elderly and persons with disabilities.[83] Several Maryland Transit Administration commuter buses also allow for access to Baltimore or Washington, D.C.

Railway

editFrom 1840 to 1968, Annapolis was connected to the outside world by railroad. The Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis Electric Railway (WB&A) operated two electrified interurban lines that brought passengers into the city from both the South and the North. The southern route ran down King George Street and Main Street, leading directly to the statehouse, while the northern route entered town via Glen Burnie. In 1935, the WB&A went bankrupt due to the effects of the Great Depression and suspended service along its southern route, while the newly created Baltimore and Annapolis Railroad (B&A) retained service on the northern route. Steam trains of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad also occasionally operated over the line to Annapolis, primarily for special Naval Academy movements. Passenger rail service on the B&A was eventually discontinued in 1950; freight service ceased in 1968 after the dilapidated trestle crossing the Severn River was condemned. The tracks were eventually dismantled in 1976.[84]

Notable people

editGovernment and politics

edit- James D. Beans, born in Annapolis, graduate of United States Naval Academy; later Brigadier general in the Marine Corps

- Sally Brice-O'Hara (born 1953), graduate of Annapolis High school, 27th Vice-Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard[85]

- Charles Carroll (1723–1783), Continental Congressman from Maryland[86]

- Charles Carroll of Carrollton (1737–1832), United States Senator and signer of United States Declaration of Independence[86]

- Pamela Chelgren-Koterba (born 1950), former officer of the NOAA Commissioned Officer Corps

- Peter K. Cullins (1928–2012), U.S. Navy admiral

- Henry Winter Davis (1817–1865), United States Representative from Maryland[86]

- Jon Eubanks, Republican member of Arkansas House of Representatives from Logan County; graduated from high school in Annapolis.[87]

- John Hall (1729–1797), born in Annapolis, delegate to the Continental Congress from Maryland[86]

- Alexander Contee Hanson (1786–1819), born in Annapolis, United States Congressman and Senator from Maryland[86]

- Samuel M. Harrington (1882–1948), born in Annapolis, USMC Brigadier General

- Reverdy Johnson (1796–1876), born in Annapolis, United States Senator from Maryland and Attorney General of the United States[86]

- Frank J. Larkin, resident of Annapolis, 40th Sergeant at Arms of the United States Senate[88]

- George K. McGunnegle, U.S. Army colonel[89]

- William Duhurst Merrick (1818–1889), born in Annapolis, lawyer, professor at George Washington University, and United States Senator from Maryland[86]

- William Paca (1740–1799), signatory to the United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland[90]

- Henry D. Todd, United States Naval Academy professor and rear admiral[91]

- Reginald H. Ridgely Jr., United States Marine Corps lieutenant general; grew up in Annapolis.

- Blake Van Leer, resident during WWII, U.S. Army colonel and Board member of United States Naval Academy

Athletes

edit- Bill Belichick (1952–), lived in Annapolis, graduate of Annapolis High School, head coach of the New England Patriots[92]

- Donald Brown (1963–), pro football player

- Daronte Jones, American football coach

- Ivan Leshinsky (born 1947), American-Israeli basketball player

- Debbie Meyer (1952–), born in Annapolis, three-time Olympic swimming gold medalist[93]

- Travis Pastrana, X Games athlete, Nitro Circus / Nitro Rallycross founder and 5x American Rally Association / Rally America Champion

- Mark Teixeira (1980–), born in Annapolis, retired professional baseball player for New York Yankees[94]

The arts

edit- John Henry Alexander (1812–1867), born in Annapolis, scientist, businessman, and author[86]

- John Beale Bordley (1727–1804), government official, farmer, and author[86]

- James M. Cain (1892–1977), born in Annapolis, author of Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce and The Postman Always Rings Twice[95]

- Michele Carey (1942–2018), born in Annapolis, actress, El Dorado, Live a Little, Love a Little

- Robert Duvall, actor, lived in downtown Annapolis[96]

- Jay Fleming, born in Annapolis, photographer[97]

- Barbara Kingsolver (1955–), born in Annapolis, novelist and poet[98]

- Iris Krasnow (1954–), author, journalism professor, and keynote speaker[99]

- Louise Platt, ( – September 6, 2003) American theater, film, and TV actress[100]

- Christian Siriano, fashion designer and winner of the fourth season of Project Runway[101]

- Thorne Smith (1892–1934), author of Topper

- Stan Stearns (1935−2012), photographer of the iconic image of a three-year-old John F. Kennedy Jr. saluting the coffin of his father, U.S. President John F. Kennedy[102]

- Leo Strauss (1899–1973), German-born Jewish political philosopher who specialized in the study of classical philosophy; spent his last three years of life teaching at St. John's in Annapolis

Others

edit- Brother Chidananda (1953–), President from the Self-Realization Fellowship and Yogada Satsang Society of India[103]

- James Booth Lockwood (1852–1884), born in Annapolis, army officer and Arctic explorer; the person who named Lockwood Island[86]

- Anne St. Clair Wright (1910–1993), long time Annapolis resident; historic preservationist in the city.

In popular culture

editThe 1955 film An Annapolis Story takes place at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis.[104]

The 2006 film Annapolis is set in the titular city.

The 2014 film Are You Here is partially set in Annapolis.[105]

See also

editExplanatory notes

edit- ^ The main weather station of Annapolis is located in Naval Academy. For details, please refer to the specific information of the weather station.[35]

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ For more information, see xmACIS2

References

edit- ^ "City Council". www.annapolis.gov. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ Garner, Bryan (2009). Garner's Modern American Usage (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 238. ISBN 9780195382754. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c "DAR Chapter Presents City With Official Banner". Evening Capital. Vol. LXXXI, no. 9. Annapolis, Maryland. January 12, 1965. p. 1. Image caption in newspaper: "City's First Flag".

- ^

David Ridgely, ed. (1841). Annals of Annapolis. Cushing & Brother. pp. 34, 35. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

In 1683 Annapolis was erected into a town, port, and place of trade, under the name of the 'Town Land at Proctors.

- ^ David Ridgely, ed. (1841). Annals of Annapolis. Cushing & Brother. pp. 34, 35. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

[Anne Arundel county] was probably so called from the maiden name of Lady Baltimore, then late deceased — Lady Anne Arundel, the daughter of Lord Arundel of Wardour, whom Cecilius Lord Baltimore had married. [...] In 1694 [the settlement] was constituted a town, port, and place of trade, under the name of Anne Arundel Town [...].

- ^

David Ridgely, ed. (1841). Annals of Annapolis. Cushing & Brother. pp. 34, 35. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

[...] the first assembly was held at Anne Arundel Town, on the 28th of February, 1694, (old style.) At the next session it acquired the name of the 'Port of Annapolis' and became the place of sessions for the courts of Anne Arundel county. [...] In this year it was enacted by the general assembly that there be one or more places laid out and reserved [...] That the naval-officer reside there; and that Anne Arundel Town for the future, should be called, known and distinguished by the name of 'Annapolis'.

- ^ Huston, John W. (1977). "Annapolis: an eighteenth-century analysis". Conspectus of History. 1 (4): 49.

- ^ Colonel John Seymour, Governor of Maryland, to Queen Anne. (16 March 1709). Colonial Office, Commonwealth and Foreign and Commonwealth Offices, Empire Marketing Board, and related bodies. Image library reference:CO 5/716 (1 of 6). The National Archives website Archived December 23, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ McWilliams, Jane W. (2011). Annapolis, City on the Severn: A History. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ William J. Cochran (2001). "Green Print Shop". Archaeology in Annapolis. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008.

- ^ "Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress". The Library of Congress. July 1, 2005. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Annapolis, a city and seaport of Maryland, U.S.A.". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 63–64. Endnotes:

- D. Ridgely, Annals of Annapolis from 1649 until the War of 1812 (Baltimore, 1841)

- S. A. Shafer, "Annapolis, Ye Ancient City", in L. P. Powell's Historic Towns of the Southern States (New York, 1900)

- W. Eddis, Letters from America (London, 1792).

- ^ J.A. Leo Lemay, Men of Letters in Colonial Maryland (1972) p 229.

- ^ Mike Peed (June 13, 2009). "A Corrected Replica of the Flag From Maryland's 1783 State House Will Be Raised". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "A John Shaw Flag for the Maryland State House" (PDF). Maryland State Archives. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Wright Jr., Robert K; MacGregor Jr., Morris J. (1987). Soldier-Statesmen of the Constitution. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History. p. 265. ISBN 978-1125939758.

- ^ Munch, Vincent A. (March 2001). "NewsLibrary2001145NewsLibrary. Internet URL: http://www.newslibrary.com: Media Stream 2000. Price: $1.95 per article (minimum) Date last accessed: 21 November 2000". Reference Reviews. 15 (3): 17. doi:10.1108/rr.2001.15.3.17.145. ISSN 0950-4125.

- ^ "Current Population Survey, August 2005: Veterans Supplement". April 4, 2008. doi:10.3886/icpsr04555.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Camp Parole Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ Tom (April 19, 2018). "Lovely 1896 Aerial View of Annapolis". Ghosts of Baltimore. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ "Henry Davis, MSA SC 3520-13635".

- ^ Xia, Rosanna (March 13, 2019). "Destruction from sea level rise in California could exceed worst wildfires and earthquakes, new research shows". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 15, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Bottalico, Brandi. "County's Battle of the Bands ends after 17 years". capitalgazette.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Williams, Timothy; Harmon, Amy (June 29, 2018). "Maryland Shooting Suspect Had Long-Running Dispute With Newspaper". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ Melser, Lowell (September 2, 2021). "Ida leaves widespread damage in Anne Arundel County Wednesday". WBAL. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ "IEM :: PNS from NWS LWX". mesonet.agron.iastate.edu. September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ "The State House and its Dome". Capital Gazette Communications, Inc. 2008. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ^ a b "History of the State House and Its Dome". Maryland State Archives. Archived from the original on November 20, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "A Brief History of St. John's College". St. John's College. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "Annapolis". Maryland Manual On-Line. Maryland State Archives. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ "Annapolis (city), Maryland 2010". State & County QuickFacts. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ "Annapolis, MD". USA.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ "Daily Summaries Station Details". NOAA. Archived from the original on July 15, 2023.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ "Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 15, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ "Station: ANNAPOLIS NAF, MD". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 15, 2023. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- ^ "Annapolis, Maryland, USA – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Beating Back the Tides". SeaLevel.NASA.gov. NASA. November 11, 2020. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. High-tide flooding is also known as tidal flooding, sunny day flooding and nuisance flooding.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Berkinshaw, Georgie. "Annapolis Area Neighborhoods and Communities". Annapolis Real Estate. Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage. Archived from the original on July 13, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "High School Sports - Capital Gazette". Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e MainStreet Annapolis Partnership. Walk Annapolis map (JPG) (Map). MainStreet Annapolis Partnership. Archived from the original on November 12, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "Eastport: A Different Side of Annapolis". visitANNAPOLIS. Visit Annapolis & Anne Arundel County. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "Home". The Maritime Republic of Eastport. Maritime Republic of Eastport. Archived from the original on May 19, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "Historic London Town: Where the Past Meets the Present". visitANNAPOLIS. Visit Annapolis & Anne Arundel County. Archived from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "Main Street: It's All Here". visitANNAPOLIS. Visit Annapolis & Anne Arundel County. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "City Dock: Quintessential Annapolis". visitANNAPOLIS. Visit Annapolis & Anne Arundel County. Archived from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "United States Naval Academy: One of Annapolis' Longest Standing Institutions". visitANNAPOLIS. Visit Annapolis & Anne Arundel County. Archived from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "United States Naval Academy". Maryland's National Register Properties. Maryland Historical Trust. 2015. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "History/Archives". St. Margaret's Church. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "State Circle/Maryland Avenue: Nothing says Annapolis quite like State Circle & Maryland Avenue". visitANNAPOLIS. Visit Annapolis & Anne Arundel County. Archived from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "Arts District". visitANNAPOLIS. Visit Annapolis & Anne Arundel County. Archived from the original on May 21, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "2020 census".

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Census.gov Archived February 10, 2020, at archive.today

- ^ "City of Annapolis CAFR". Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Rebecca Wyrick (December 12, 2012). "Theatre Review: 'A Christmas Carol' at Colonial Players of Annapolis". MD Theatre Guide. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Our History". The Colonial Players, Inc. Archived from the original on February 17, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "About Us: Our History". Annapolist Summer Garden Theatre. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Danielle Angeline (August 8, 2013). "Theatre Review: 'Into the Woods' at Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre". MD Theatre Guide. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "About Our Theatre". Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Naval Academy Masquerader's opening performance tonight". Baltimore News Journal. November 15, 2013. Archived from the original on November 21, 2013.

- ^ "Annapolis Theater: King William Players". St. John's College. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Banneker-Douglass Museum 30th Anniversary". Maryland Commission on African American History and Culture. November 7, 2013. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ "USNA Museum". U.S. Naval Academy. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "The Palladian Connection". Hammond-Harwood House Association, Inc. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ "Visit Hammond-Harwood". Hammond-Harwood House Association, Inc. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Mahood, Kate; Keller, Genevieve (September 11, 2018). Annapolis City Dock Cultural Landscape Report (Report). Annapolis, MD. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018.

- ^ Urban Land Institute (October 2018). "Reclaiming a Local and National Treasure — Annapolis City Dock" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Kunta Kinte-Alex Haley Memorial". Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Governor William Paca House and Garden". Maryland Historical Trust. Archived from the original on November 26, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "Around Maryland". The Washington Post. 1995.

- ^ "Major League Lacrosse: Bayhawks top Long Island to earn 2010 MLL Championship". Inside Lacrosse. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010.

- ^ "Parks and Trails". Archived from the original on October 23, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ Knisley, Nancy. "Trails, acres of parkland crisscross the landscape". baltimoresun.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Explore The County's Parks | Anne Arundel County, MD". www.aacounty.org. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "Annual Events, Festivals And Local Traditions| Historic Downtown Annapolis". www.downtownannapolis.org. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ "Annapolis Council To Consider Stripping Republican Mayor-Elect's Power". Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ Lisa Robinson (April 15, 2012). "Calls for weak-mayor system in Annapolis come days after election". WBAL-TV. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ "Contacts". www.aacps.org. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "Annapolis.md.us". Archived from the original on January 7, 2010.

- ^ Schwieterman, Joseph P. (2001). When the Railroad Leaves Town: American Communities in the Age of Rail Line Abandonment, Eastern United States. Kirksville, Missouri: Truman State University Press. pp. 109–113. ISBN 978-0-943549-97-2.

- ^ Sun, Candus Thomson, The Baltimore. "The Interview: Sally Brice-O'Hara". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- ^ "Jon Eubanks, R-74". arkansashouse.org. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Frank J. Larkin - SAA". January 2, 2015.

- ^ Who Was Who in America. Vol. 4. Chicago, IL: Marquis Who's Who. 1968. p. 639.

- ^ Rev. Charles A. Goodrich (1856). "Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence". Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ^ "Recent Deaths: Henry Davis Todd". Army and Navy Journal. New York, NY. March 23, 1907. p. 812 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Bill Belichick". New England Patriots. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Craig Lord (August 7, 2007). "Memories, Momentum and Magnitude of Meyer". SwimNews. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ^ "Distinguished Americans & Canadians of Portuguese Descent". Portuguese Foundation. Archived from the original on March 15, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ^ "James M. Cain". University of Maryland. Archived from the original on August 20, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ^ Rhys, Timothy E. (May 2003). "Robert Duvall: Soldier of Fortune". MovieMaker Magazine. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved October 16, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Woolever, Lydia (August 23, 2021). "Photographer Jay Fleming Captures the World of Water on the Chesapeake". Baltimore Magazine. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- ^ "About Barbara: Biography". Barbara Kingsolver official website. Archived from the original on June 16, 2006. Retrieved June 18, 2006.

- ^ "Iris Krasnow's book, 'The Secret Lives of Wives,' looks at how long-lasting marriages survive", by Ellen McCarthy, The Washington Post, October 21, 2011

- ^ "Louise Platt, 88: Last Survivor of Passengers in Movie 'Stagecoach'". The Los Angeles Times. California, Los Angeles. September 25, 2003. p. B 12. Retrieved September 12, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ White, Tanika (November 13, 2007). "Sheer Talent". The Baltimore Sun.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Flegenheimer, Matt (March 5, 2012). "Stan Stearns, 76; Captured a Famous Salute". The New York Times. p. B10.

- ^ yogananda-srf.org: "SRF Announces New President". September 1, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- ^ "An Annapolis Story (1955)". TCM.com. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Edelstein, David (August 22, 2014). "Is It Possible for Matthew Weiner to Be Matthew Weiner on the Big Screen?". Vulture.com. Vox Media. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

Further reading

edit- Eric L. Goldstein, Traders and Transports: The Jews of Colonial Maryland (Baltimore: Jewish Historical Society of Maryland, 1993).

External links

edit- Annapolis official website

- Geographic data related to Annapolis, Maryland at OpenStreetMap

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Claude-Gray-Hughes-Tuck-Whittington Family papers, the papers of five 19th-century Annapolis families who were interrelated by marriage, at the University of Maryland libraries