Andersonville is a city in Sumter County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 237. It is located in the southwest part of the state, approximately 60 miles (97 km) southwest of Macon on the Central of Georgia railroad. During the American Civil War, it was the site of a prisoner-of-war camp, which is now Andersonville National Historic Site.

Andersonville, Georgia | |

|---|---|

City | |

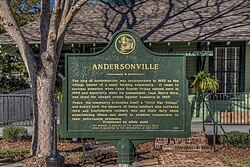

Andersonville historical marker | |

Location in Sumter County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 32°11′49″N 84°8′30″W / 32.19694°N 84.14167°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Sumter |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Brandon Gross |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.39 sq mi (3.59 km2) |

| • Land | 1.38 sq mi (3.57 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.02 km2) |

| Elevation | 397 ft (121 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 237 |

| • Density | 171.74/sq mi (66.33/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 31711 |

| Area code | 229 |

| FIPS code | 13-02256[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0354310[3] |

| Website | andersonvillegeorgia.com |

Andersonville is part of the Americus micropolitan statistical area.

History

editThe hamlet of Anderson was named for John Anderson, a director of the South Western Railroad in 1853 when it was extended from Oglethorpe to Americus. It was known as Anderson Station until the US post office was established in November 1855. The government changed the name of the station from "Anderson" to "Andersonville" in order to avoid confusion with the post office in Anderson, South Carolina.[4]

During the Civil War, the Confederate army established Camp Sumter at Andersonville to house incoming Union prisoners of war. The overcrowded Andersonville Prison was notorious for its bad conditions, and nearly 13,000 prisoners died there.[5] After the war, Henry Wirz was convicted for war crimes related to the command of the camp. His trial was later regarded as unfair by several pro-confederacy groups,[6] and a monument in his honor has been erected in Andersonville by the United Daughters of the Confederacy.[7][8]

The town also served as a supply depot during the war period. It included a post office, a depot, a blacksmith shop and stable, a couple of general stores, two saloons, a school, a Methodist church, and about a dozen houses. Ben Dykes, who owned the land on which the prison was built, was both depot agent and postmaster.[9]

Until the establishment of the prison, the area was entirely dependent on agriculture, supported by dark reddish brown sandy loams later mapped as Greenville and Red Bay soil series. After the close of the prison and end of the war, the town continued economically dependent on agriculture, primarily the cultivation of cotton as a commodity crop.

It was not until 1968, when the large-scale mining of kaolin, bauxitic kaolin, and bauxite was begun by Mulcoa, Mullite Company of America, that the town was dramatically altered. This operation exploited 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) of scrub oak wilderness into a massive mining and refining operation. The company now[when?] ships more than 2000 tons of refined ore from Andersonville each week.

In 1974, long-time mayor Lewis Easterlin and a group of concerned citizens decided to promote tourism in the town, redeveloping Main Street to look much as it did during the American Civil War. The city of Andersonville and the Andersonville National Historic Site, location of the prison camp, are now tourist attractions.

Geography

editClimate

edit| Climate data for Andersonville, Georgia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 60 (16) |

62 (17) |

70 (21) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

91 (33) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

88 (31) |

79 (26) |

68 (20) |

61 (16) |

77 (25) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 38 (3) |

40 (4) |

46 (8) |

53 (12) |

61 (16) |

68 (20) |

71 (22) |

70 (21) |

66 (19) |

55 (13) |

44 (7) |

39 (4) |

54 (12) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.3 (110) |

4.8 (120) |

5.3 (130) |

3.9 (99) |

3.5 (89) |

4.3 (110) |

5.5 (140) |

4.9 (120) |

3.4 (86) |

2.3 (58) |

2.7 (69) |

4.0 (100) |

48.9 (1,240) |

| Source: Weatherbase[10] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 308 | — | |

| 1900 | 245 | — | |

| 1910 | 174 | −29.0% | |

| 1920 | 196 | 12.6% | |

| 1930 | 231 | 17.9% | |

| 1940 | 211 | −8.7% | |

| 1950 | 281 | 33.2% | |

| 1960 | 263 | −6.4% | |

| 1970 | 274 | 4.2% | |

| 1980 | 267 | −2.6% | |

| 1990 | 277 | 3.7% | |

| 2000 | 331 | 19.5% | |

| 2010 | 255 | −23.0% | |

| 2020 | 237 | −7.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[11] | |||

As of the census[2] of 2000, there were 331 people, 124 households, and 86 families residing in the city. The population density was 254.1 inhabitants per square mile (98.1/km2). There were 142 housing units at an average density of 109.0 per square mile (42.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 65.26% White and 34.74% African American. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.21% of the population.

There were 124 households, out of which 34.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.0% were married couples living together, 17.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.6% were non-families. 26.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.67 and the average family size was 3.21.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.8% under the age of 18, 9.4% from 18 to 24, 31.4% from 25 to 44, 19.3% from 45 to 64, and 12.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 105.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $29,107, and the median income for a family was $30,972. Males had a median income of $26,591 versus $20,000 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,168. About 19.8% of families and 23.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.3% of those under age 18 and 13.5% of those age 65 or over.

References

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-915430-00-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Hickman, Kennedy (May 16, 2016). "American Civil War: Andersonville Prison". ThoughtCo.com. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Moyer, Justin Wm.; Giroud, Tara E.M. (February 10, 2022). "Confederate war criminal buried in D.C. has an unlikely defender: A Swiss descendant". Washington Post. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ Bailey, Greg (November 10, 2015). "Why Does This Georgia Town Honor One of America's Worst War Criminals?". The New Republic. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ Eschner, Kat (November 10, 2017). "How the Trial and Death of Henry Wirz Shaped Post-Civil War America". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "Reading 1: Andersonville Prison". National Park Service. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ "Andersonville, Georgia Travel Weather Averages". weatherbase.com. Great Falls, VA, US: Weatherbase, Canty and Associates LLC. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.